Translate this page into:

Morphological and molecular approaches for identification of murine Eimeria papillata infection

⁎Corresponding authors. mfelkhadragy@pnu.edu.sa (Manal F. El-khadragy), rabdelgaber.c@ksu.edu.sa (Rewaida Abdel-Gaber)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Oocysts recovered from Mus musculus were morphologically described and molecularly characterized using 18S rDNA and ITS1 regions. Sporulated oocysts had two layers and were sub-spherical measuring 20.76 (19.41–22.33) × 17.46 (15.44–19.15) μm with a length/width index of 1.18. Sporocysts were with stieda and substieda bodies with sporocystic residuum. Molecular data from both 18S rDNA and ITS1 regions revealed that the species under investigation is related to Eimeria papillata. The 18S rDNA sequences obtained in this investigation were identical to an E. papillata sequence from M. musculus found in GenBank. The sequence obtained from the ITS-1 region showed a slight difference from other sequences from E. papillata for the same region with a similarity percent of 97.2% to 100%. The AT content of the ITS1 region from the present study was found to be 53.1%. According to ITS1 data, 10 haplotypes were characterized with haplotype diversity (Hd) of 0.9271. Sequences of the ITS1 region from E. papillata were variable in 18 sites with 3 indels, of those variable sites 15 were transitions while 3 were transversions. Therefore; the ITS1 region is probably a good marker for differentiating different strains of Eimeria species in rodents.

Keywords

Apicomplexa

Eimeria papillata

Rodents

Morphology

PCR

18SrDNA

ITS1

1 Introduction

Apicomplexa Levine, 1970 is a large protist phylum that includes a wide range of obligatory parasitic organisms (Gillies et al., 2003). Eimeria is the most significant protozoan apicomplexan parasite. With over 1700 species reported, the Eimeria genus is common across vertebrate hosts. Eimeria species have a high degree of host and site specificity (López-Osorio et al., 2020). In 1971, Ernst and his colleagues identified Eimeria papillata as a coccidian parasite in the house mouse (Mus musculus). Infections begin with the oral uptake of eimerian oocysts, which release sporozoites in the jejunal mucosa, where they proliferate and cause enteric diseases (Allen and Fetterer, 2002), and finally, oocysts are released again with the feces (Stafford and Sundermann, 1991).

The traditional methods have been used to identify most Eimeria species such as oocyst morphological traits, the pre-patent period of the parasite, the host and site-specificity, the clinical features of the host, and the typical macroscopic lesions that are assessed by the role of lesion score during necropsy, host range, and life-cycle attributes (Gardner and Duszynski, 1990; Upton et al., 1992; Duszynski and Wilber, 1997). These earlier studies laid the foundation for Eimeria classification. Natural Eimeria infections, on the other hand, are frequently combined with more than one species, whose morphological traits and pathological alterations may be identical, making identification of the species difficult (Woods et al., 2000; Williams, 2001; Carvalho et al., 2011). Several eimerian species cannot be differentiated by microscopic description due to the similar morphology and the overlapping morphometrics of the oocysts.

To describe the identity of Eimeria and complement prior morphological descriptions, molecular techniques are increasingly being applied (López et al., 2007; Power et al., 2009). These techniques have some advantages over previous traditional methods in that they solely use the Eimeria species’ genetic sequence. Several approaches based on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been published that use primers to target particular regions of the Eimeria genome (Ogedengbe et al., 2011). The use of nuclear and mitochondrial genetic markers such as 5.8S rRNA (Stucki et al., 1993; Tsuji et al., 1999), small subunit (18S) rRNA (López et al., 1999; Ogedengbe et al., 2018), internal transcribed spacer (ITS)-1 and 2 (Gasser et al., 2001; Lew et al., 2003; Su et al., 2003; Lien et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2015), and cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) (Tan et al., 2017) have been introduced to be effective in identification and taxonomic classification of protozoan parasites, including Eimeria. Genetic information not only helps to establish a more stable Eimeria taxonomy but also sheds light on the parasite’s evolutionary relationships.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to describe oocysts of Eimeria papillata infecting laboratory mice and confirm the identification using molecular methods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Coccidian parasite

The coccidian parasite used in this study was a laboratory strain of Eimeria papillata maintained by the periodic passage through coccidian-free mice in Parasitology Laboratory Research (Zoology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). Unsporulated oocysts were recovered from the fecal matter of laboratory mice five days after infection and allowed to sporulate in 2.5% (w/v) potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) at 24 °C according to Long et al. (1976) for utilization in the experiment. After sporulation, sporulated oocysts were recovered by centrifugation in saturated saline solution at 250 × g for 5 min followed by washing with distilled water (Schito et al., 1996).

2.2 In vivo propagation of Eimeria oocysts

All samples containing sporulated oocysts were used for in vivo propagation as a consequence of overall low oocyst recovery. A total of 5 male laboratory mice (Mus musculus, aged 9–12 weeks) were used for passaging of the parasite in this experiment. The number of the acquired oocysts was adjusted such that each mouse was orally given 1 × 103 sporulated oocysts in 100 µl of physiological saline (Abdel-Tawab et al., 2020). Oocysts were recovered from the fecal material of experimental animals five days after infection using standard procedures (Schmnatz et al., 1984) to be sporulated, purified, and then stored at 4 °C for subsequent study.

2.3 Morphology and morphometry

Fecal samples from mice infected with Eimeria papillata were collected and preserved in a 2.5% K2Cr2O7 solution. Samples were examined for oocysts using a flotation technique with Sheather’s sugar-saturated solution (SG 1.30) (MAFF, 1986). The collected oocysts were kept in a shallow layer of 2.5% K2Cr2O7 to allow sporulation of oocysts (Mohammed and Hussein, 1992). The oocysts in the samples were checked daily for sporulation through microscopic examination. Oocysts were photographed using Olympus compound microscope supplied with CP72 digital camera (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The main morphological features were described, according to the protocol of Duszynski and Wilber (1997). Measurements from 50 oocysts and 50 sporocysts were done using a calibrated ocular micrometer.

3 Molecular methods

3.1 Oocysts’ purification and DNA extraction

Recovered oocysts were washed five times to wash the K2Cr2O7 till the supernatant was clear by centrifugation at 6000 × g. Purified oocysts were subjected to DNA extraction using the method involving lysis buffer and Cetyl–Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide (CTAB) buffer (2% w/v CTAB, 1.4 M NaCl, 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM EDTA, 100 mM TRIS) as suggested by Zhao et al. (2001a) with a slight modification where 1.3 N-Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate (SDS) was used instead of 1.3% N-lauroylsarcosine. The purified oocysts were treated with sodium hypochlorite and incubated in the lysis buffer for 45 min at 65 °C. Then 350 μl of CTAB buffer was added and incubated for a further 1 hr at 65 °C. Then the DNA was extracted using Isolate II fecal DNA extraction kit from Meridian Bioscience (London, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

3.2 Polymerase chain reaction, DNA sequencing, and data analysis

The Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for the amplification of the Internal Transcribed Spacer 1 (ITS1) using the forward primer 5′-GCAAAAGTCGTAACACGGTTTCCG-3′, with a reverse primer 5′-CTGCAATTCACAATGCGTATCGC-3′ (Kawahara et al., 2010). The expected amplicon size for the ITS1 region is ∼ 380 bp including the 5.8S region. The amplification of the partial 18S subunit ribosomal RNA region was brought about by using primers; F1E 5′-TACCCAATGAAAACAGTTT-3′ as a forward primer and R2B 5′-CAGGAGAAGCCAAGGTAGG-3′ as a reverse primer (Orlandi et al., 2003). The expected amplicon size of the 18S rDNA region is ∼ 636 bp.

The PCR products from each reaction using both genes (ITS1, 18S rDNA) were purified and cycle-sequenced using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA), and run on an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at the Molecular Biological Unit of the Prince Naif Health Research Center, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Generated sequences were compared with related sequences of Eimeria spp. available in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using BLAST. Multiple sequence alignments were made using Clustal W (Thompson et al., 1994), and phylogenetic trees were generated using MEGA version X (Kumar et al., 2018) using the best-fitting models and 1,000 replicates to evaluate the bootstrap analysis using neighbor-joining and maximum likelihood. The relevant ITS1 sequences of E. papillata available in GenBank were obtained and the haplotype network was conducted using Population Analysis with Reticulate Trees (PopART) software available at http://popart.otago.ac.nz using Templeton, Crandall, and Sing (TCS) option (Leigh and Bryant, 2015).

3.3 Statistical analysis

Measurements of length, width, and shape-index of the oocysts and sporocysts were analyzed using the SPSS v.18 software program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and the values were presented in micrometers (µm) as the mean with the range in parentheses.

4 Results

Experimental mice started shedding unsporulated oocysts after three days post-infection (PI). On day 5 PI, the maximum rate of oocyst shedding was 1769430 ± 60425 oocyst per gram of feces which then declined gradually in the following days. No oocysts were recovered from feces on day 12 PI. There were no symptoms of diarrhea or soft droppings which indicated that the parasite with no observable pathogenicity. The sporulation rate was recorded within the range of 80–90%. Following sporulation, oocysts were described in detail as mentioned below.

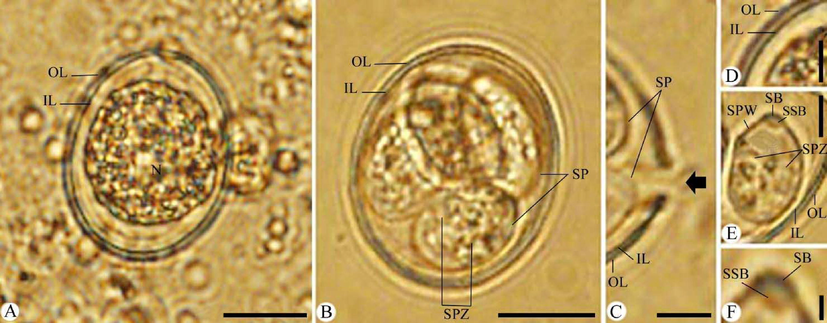

Description (Fig. 1).

Photomicrographs of Eimeria papillata oocysts. (A) Unsporulated oocyst. (B) Sporulated oocyst. (C) Site of splitting sporocysts during excystation (Black arrow). (D-F) High magnifications for (D) Oocyst bi-layered. (E) Sporocyst. (F) Stieda body of sporocyst. Note: IL, inner layer; OL, outer layer; SB, stieda body, SP, sporocysts; SPW, sporocyst wall; SPZ, sporozoite. Scale bar = 10 μm (A and B) and 5 μm (C-F).

4.1 Oocysts

Oocysts are sub-spherical in shape and surrounded by a thick bi-layered wall. Sporulated oocyst is 20.76 (19.41–22.33) long, 17.46 (15.44–19.15) wide, and oocyst length/width (L/W) index 1.18. Oocysts are tetrasporocystic and disporozoic. Micropyle, oocyst residuum, and polar granules are absent. Measurements and oocysts features are similar to those of E. papillata as shown in Table 1. M = micropyle; MC = micropylar cap; PG = polar granule/s; OR = oocysts residuum; SB = stieda body; SSB = substieda body; SR = sporocyst residuum. +=present; -= absent; += present or absent;?= not specified.

Eimeria spp. from Mus musculus

oocyst

sporocyst

Measurements

M

MC

PG

OR

SB

SSB

SR

Eimeria arasinaensis Musaev & Veisov, 1965

12–24 × 10–20 (19 × 16)

+

+

+

–

–

?

–

Eimeria baghdadensis Mirza, 1975

20–24 × 17–20 (22 × 18)

–

–

+

–

+

?

+

Eimeria contorta Haberkorn, 1971

Mixture of E. nieschulzi and E. falciformis

–

–

+

–

+

?

Eimeria falciformis (Eimer, 1870) Schneider, 1875

14–27 × 11–24

–

–

–

–

+

?

+

Eimeria ferrisi Levine & Ivens, 1965

12-22X11-18 (17–18 × 14–15)

–

–

–

–

+

?

+

Eimeria hansonorum Levine & Ivens, 1965

15–22 × 13–19 (18 × 16)

–

–

+

–

+

?

+

Eimeria hindlei Yakimoff & Gousseff, 1938

22–27 × 18–21

–

–

+

–

+

?

+

Eimeria keilini Yakimoff & Gousseff, 1938

24–32 × 17–21

–

–

–

?

Eimeria krijgsmanni Yakimoff & Gousseff, 1938

18–23 × 13–16 (22 × 15)

–

–

+

–

?

+

Eimeria musculi Yakimoff & Gousseff, 1938

21 × 26

–

–

–

–

?

Eimeria musculoidei Levine, Bray, Ivens, & Girnders, 1959

17–23 × 15–19 (20 × 17)

–

–

+

–

?

+

Eimeria papillata Ernst, Chobotar, & Hammond, 1971

18–26 × 16–24 (22 × 19)

–

–

+

–

+

+

+

Eimeria paragachaica Musaev & Veisov, 1965

24–32 × 18–24 (28 × 22)

+

+

+

+

+

?

+

Eimeria schueffneri Yakirnoff & Gousseff, 1938

18–26 × 15–16

–

–

–

–

–

?

Eimeria tenella (Railliet & Lucet, 1891) Fantham, 1909

?

Eimeria vermiformis Ernst, chobotar, & hammond, 1971

18–26 × 15–21 (23 × 18)

–

–

+

–

+

?

+

Eimeria sp. Musaev & Veisov, 1965

16–22 × 14–18 (21 × 17)

–

+

?

+

Eimeria sp. Veisov, 1973

12–23 × 10–20 (17–14)

+

?

?

?

4.2 Sporocysts and sporozoites

Sporocysts are ellipsoidal with a single-layered wall. Sporocyst is 9.76 (8.69–10.35) long, 6.54 (5.81–8.35) wide, and sporocyst (L/W) index is 1.49. Stieda body is broad, measured 0.23 (0.20–0.25) long and 1.02 (1.01–1.03) wide. Sub-stieda body is rectangular shape, measured 0.56 (0.53–0.58) long and 0.94 (0.90–0.95) wide. Sporocysts residuum is composed of small granules dispersed between sporozoites. Sporozoites are sausage-shaped with non-discernible nuclei and a refractile body.

4.3 Molecular data and analysis

A PCR product of 636 bp and 380 bp were successfully amplified from the 18S rDNA and the ITS1 regions, of the DNA extracted from sporulated oocysts and sequenced. Edited sequences input files included 609 and 369 characters for 18S rDNA and ITS1 regions including 25 and 21 sequences respectively for the analysis.

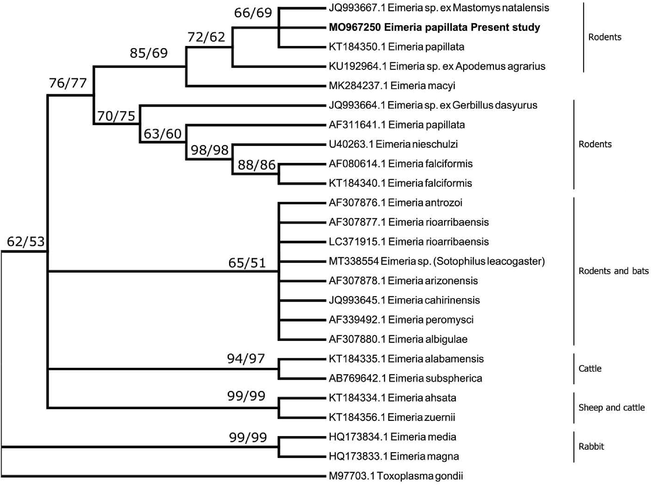

A BLAST search of the 18S rDNA sequences showed identity to the sequence from Eimeria papillata isolate (KT184350.1) and to that sequence from an eimerian species from the Natal multimammate mouse (Mastomys natalensis). Similar sequences from other species of wood mice showed identity with the sequences with>99% similarity. Another sequence which was identified as E. papillata from M. musculus (AF311641.1) clustered with other eimerian species from M. musculus and Rattus norvegicus. A sequence from E. mayci which was reported from the eastern pipistrelle bat Pipistrellus subflavus, from Alabama was found to group with similar sequences from wood mouse (Apodemus sp.) as well as M. musculus (Fig. 2).

A consensus phylogenetic tree from 18S rDNA data constructed with neighbor-joining (NJ) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods, showing the phylogenetic relationships of the Eimeria papillata recovered in the present study from Mus musculus with other related eimerian parasites from GenBank, using Toxoplasma gondii as an outgroup. Numbers indicated at branch nodes are bootstrap values of NJ followed by ML. Sequences from the present study are in bold. Only bootstraps > 50% are shown.

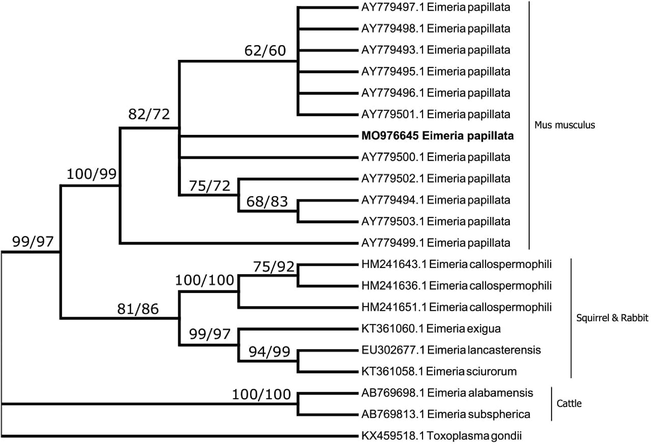

A BLAST search of the ITS1 region yielded the best match for the 5.8S region (82 bp) for various strains of E. papillata (from Mus musculus), Eimeria callospermophili, Eimeria lancasterensis, and Eimeria sciurorum (from squirrels), Eimeria subspherica, and Eimeria albamaensis (from cattle), Eimeria exigua (from rabbits) as well as an undescribed eimerian species from bats. However, E. papillata together with the sequence obtained in the present study clustered together forming a distinct clade. Sequences from the ITS1 region obtained in the present study showed homology to the 11 sequences of ITS1 from E. papillata in GenBank (AY779493.1 to AY779503.1) with identities of 97.2% to 100%. The variation between different strains was in 19 variable sites together with one insertion at position 15 in the sequence AY779501.1 of the alignment (Table 2). The AT content of the ITS1 sequence obtained in the present study was found to be 53.1% while the average AT content of all ITS1 sequences of E. papillata sequences was 53.7. The percentage of variation in the strains of E. papillata as revealed from different sequences was found to be 4.8%. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the ITS1 sequence obtained in the present study grouped with those sequences related to E. papillata with a very strong bootstrap value (Fig. 3).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Eimeria papillata This study

AY779493.1 Eimeria papillata

99.4

AY779494.1 Eimeria papillata

98.1

98.1

AY779495.1 Eimeria papillata

98.3

98.3

97.2

AY779496.1 Eimeria papillata

99.4

100

98.1

98.3

AY779497.1 Eimeria papillata

99.1

99.7

97.8

98.1

99.7

AY779498.1 Eimeria papillata

99.1

99.1

97.2

98.1

99.1

98.9

AY779499.1 Eimeria papillata

98.3

98.3

96.4

97.2

98.3

98.1

98.1

AY779500.1 Eimeria papillata

98.1

98.1

98.9

97.2

98.1

97.8

97.2

96.4

AY779501.1 Eimeria papillata

99.1

99.7

97.8

98.1

99.7

99.4

98.9

98.1

97.8

AY779502.1 Eimeria papillata

98.1

98.1

99.4

97.2

98.1

97.8

97.2

96.4

98.9

97.8

AY779503.1 Eimeria papillata

98.1

98.1

100

97.2

98.1

97.8

97.2

96.4

98.9

97.8

99.4

A consensus phylogenetic tree from ITS1 data constructed with neighbor-joining (NJ) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods, showing the phylogenetic relationships of the Eimeria papillata recovered in the present study from Mus musculus with other related eimerian parasites from GenBank, using Toxoplasma gondii as an outgroup. Numbers indicated at branch nodes are bootstrap values of NJ followed by ML. Sequences from the present study are in bold. Only bootstraps > 50% are shown.

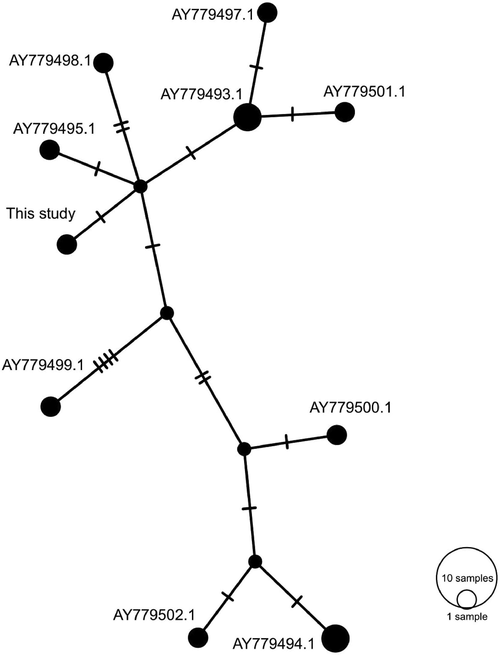

A haplotype network of ITS1 gene diversity in E. papillata isolates is shown in Fig. 4. The number of sites in the ITS1 region included 370 bp. The number of mutations at the sites analyzed was 19 sites with one base insertion. The set of 12 isolates including the one from the present study showed sequence variations in 18 sites with three insertion/deletion as shown in the different haplotypes with the isolate in the present study being a distinct haplotype. Of those variable sites, 15 sites were transitions whereas the other 3 were transversions (Table 3).

Network analysis of the nuclear ITS1 haplotypes of E. papillata. Together with sequences of the same region available in GenBank. The analysis was performed using PopART software using the TCS option for haplotypes presentation. A sequence from the present study was given in bold.

Sequence

15

40

42

45

47

63

65

83

87

109

118

161

173

239

247

249

251

252

285

286

326

This study

–

A

C

T

C

A

T

C

G

A

A

C

T

G

T

C

T

T

A

A

A

AY779493.1

–

A

T

C

C

A

T

C

G

A

A

C

T

G

T

C

T

T

A

A

A

AY779494.1

–

A

C

C

C

G

T

C

G

A

A

C

T

G

T

G

C

C

A

T

G

AY779495.1

–

A

T

T

C

A

T

C

G

A

A

C

T

G

T

G

T

T

–

–

A

AY779496.1

–

A

T

C

C

A

T

C

G

A

A

C

T

G

T

C

T

T

A

A

A

AY779497.1

–

A

T

C

C

A

T

C

G

A

A

C

G

G

T

C

T

T

A

A

A

AY779498.1

–

A

T

T

T

A

C

C

G

A

A

C

T

G

T

C

T

T

A

A

A

AY779499.1

T

G

T

T

C

A

T

T

G

G

G

C

T

A

C

C

T

T

A

A

A

AY779500.1

–

A

C

C

C

A

T

C

G

A

A

C

T

G

T

G

C

C

A

T

A

AY779501.1

–

A

T

C

C

A

T

C

C

A

A

C

T

G

T

C

T

T

A

A

A

AY779502.1

–

A

C

C

C

G

T

C

G

A

A

T

T

G

T

G

C

C

A

T

A

AY779503.1

–

A

C

C

C

G

T

C

G

A

A

C

T

G

T

G

C

C

A

T

G

Representative samples of both 18S rDNA and ITS1 sequences obtained in the present study were deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers OM967250 and OM976645 respectively.

5 Discussion

Morphological characteristics and measurements of oocysts detected in the present study indicated that they look similar to oocysts of Eimeria papillata described by Levine and Ivens (1990) and additionally to the description of Dkhil (2015) for the morphology of both sporulated and unsporulated Eimeria oocysts. Morphologically it was different from other Eimeria parasites which were described in the Mus musculus. DNA data from the 18S rDNA sequences revealed that the organism under investigation grouped with E. papillata from M. musculus and African furred mouse forming a separate clade from Eimeria parasites from M. musculus, wood mouse, and bats. Likewise, data obtained from the ITS1 region revealed that the organism under investigation relates to E. papillata from M. musculus.

DNA sequences of both 18S rDNA as well as ITS1 which were reported in the present study were identical to some 18S rDNA sequences and homologous to ITS1 sequences of E. papillata in GenBank. Some of the sequences from eimerian parasites of bats clustered with those sequences obtained from rodents, particularly in the 18S rDNA phylogenetic tree. The close phylogenetic relationship between the bats and rodent eimerian parasites has been first shown by Zhao et al. (2001b). They postulated that eimerian species from bats may have been derived from rodents Eimeria as a result of transfer between the two groups of animals. The 18S rDNA phylogenetic tree indicates that the sequence obtained in the present study falls in the same clade which included E. papillata from M. musculus (KT184350.1) and an eimerian species from the African soft-furred mouse (Mastomys natalensis). However, the other 18S rDNA sequence which is available in GenBank (AF311641.1) clustered with another group of eimerian parasites from M. musculus and R. norvegicus. This might be because either the organism from which the sequence was obtained was either misidentified or mislabeled. In the first instance where the 18S DNA sequence grouped with the sequence obtained from the African-furred mouse, the E. papillata sequence was obtained from laboratory raised mice whereas in the other instance the source of the sequence was not identified and it could be from some wild rodents in which case it could either another strain of E. papillata or probably a species belonging to E. facliformis, E. ferrisi or E. vermiformis and was identified as E. papillata. Especially the sizes of their oocysts overlap. However, Jarquín-Díaz et al. (2020) concluded that the 18S rDNA, as well as the cytochrome oxidase 1 sequences, are not sufficiently variable to differentiate parasite isolates that would be regarded as separate species based on host usage. In the present study, we found that there were 7 variable sites between the E. papillata sequence we reported and those reported by Zhao et al. (2001b).

Analysis of the ITS1 sequence data revealed that the sequence obtained grouped with 11 strains of E. papillata from Mus musculus. The eleven sequences in GenBank were from a single study and they showed variation with the sequence obtained in the present study. Sequences from all those strains including the sequence obtained in the present study grouped in one group with two clades. The pairwise distance value for ITS1 sequences analyzed was found to be 4.8%. It was previously suggested by Hnida and Duszynski (1999) that the pairwise distance values for ITS1 sequences of different rodents’ eimerian parasites ≤ 5% are evidence supporting the conspecificity of strains of similar morphology. The value obtained in the present study is in line with the suggestion of Hnida and Duszynski (1999) which was previously supported by Motriuk-Smith et al. (2009) on their findings when studying the eimerian parasites in tree squirrels (Sciurus niger) and with Mohammed et al. (2020) when studied an unidentified eimerian parasite from the bat (Scotophilus leucogaster). Additional markers were to be used with the ITS1 marker to have further information supporting the validation of the hypothesis suggested by Hnida and Duszynski (1999) as indicated in Mohammed et al. (2020) as well as what we followed in the present study. The AT content of the sequences from E. papillata was 53.7% and the AT content of eimerian parasites of rodents, in general, ranged between 52 and 54% which is different from other eimerian parasites from other animals such as poultry and bovines (Kawahara et al., 2010).

ITS1 sequences obtained in the present study together with related sequences have shown that there were ten haplotypes (I–X) based on sequence variation in the ITS1 region with average haplotype diversity (Hd) of 0.9271. There were 11 ITS1 sequences related to E. papillata in GenBank which were analyzed to assign different haplotypes.

The nuclear marker 18S rDNA is commonly used to infer phylogenetic relationships between different apicomplexan parasites (Morrison, 2009). Since it is highly conserved, it is regarded unsuitable to resolve relationships between closely related species (Zhao and Duszynski, 2001). The ITS1 marker, however, is characterized by having high variability and certain features such as AT contents for different groups of organisms hence more phylogenetic informative sites. Hence, using both markers in the present study was advantageous in resolving the identity of E. papillata confirming morphological description.

Based on the morphological description as well as molecular data it was evident that the species under investigation was E. papillata which was obtained from M. musculus.

6 Conclusion

Oocysts recovered from M. musculus in the present study were found to be related or similar to those of E. papillata reported from the house mice by Levine and Ivens (1990); furthermore, molecular data revealed that the DNA sequences obtained from those oocysts grouped with sequence data obtained from E. papillata on previous studies. The 18S rDNA sequence obtained in the present study was identical to a sequence obtained from E. papillata from M. musculus confirming the morphological identity of the organism. The pairwise distance value for ITS1 sequences of E. papillata in GenBank was found to be less than 5% confirming the hypothesis of Hnida and Duszynski (1999).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R23), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and also was supported by Researchers Supporting Project (RSP-2021/25), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- In vivo and in vitro anticoccidial efficacy of Astragalus membranaceus against Eimeria papillata infection. J. King Saud Uni. Sci.. 2020;32(3):2269-2275.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in Biology and Immunobiology of Eimeria species and in Diagnosis and control of infection with these coccidian parasites of poultry. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.. 2002;15(1):58-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular diagnosis of Eimeria species affecting naturally infected Gallus gallus. Genet. Mol. Res.. 2011;10(2):996-1005.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex-determined susceptibility and differential MUC2 mRNA expression during the course of murine intestinal eimeriosis. Parasitol. Res.. 2015;114(1):283-288.

- [Google Scholar]

- A guideline for the preparation of species descriptions in the Eimeriidae. J. Parasitol.. 1997;83(2):333-336.

- [Google Scholar]

- The sporozoan Eimeria tenella (Coccidium tenellum) parasitic in the alimentary canal of the grouse. Proc. Zool. Soc. London. Abstr. 1909:43-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymorphism of eimerian oocysts can be a problem in naturally infected hosts: an example from subterranean rodents in Bolivia. J. Parasitol.. 1990;76(6):805-811.

- [Google Scholar]

- Automated, fluorescence-based approach for the specific diagnosis of chicken coccidiosis. Electrophoresis. 2001;22(16):3546-3550.

- [Google Scholar]

- Six years of intensive pest mammal control at Trounson Kauri Park, a Department of Conservation “mainland island”, June 1996-July 2002. N. Z. J. Zool.. 2003;30(4):399-420.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zur Wirtsspezifit5t von Eimeria contorta n.sp, (Sporozoa : Eimeriidae) Z. Parasitenkde. 1971;37:303-314.

- [Google Scholar]

- Taxonomy and systematics of some Eimeria species of murid rodents as determined by the ITS1 region of the ribosomal gene complex. Parasitology. 1999;119(4):349-357.

- [Google Scholar]

- Generalist Eimeria species in rodents: Multilocus analyses indicate inadequate resolution of established markers. Ecol. Evol.. 2020;10(3):1378-1389.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic analysis and development of species–specific PCR assays based on ITS1 region of Eimeria parasites. Vet. Parasitol.. 2010;174:49-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2018;35(6):1547-1549.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic diversity within ITS-1 region of Eimeria species infecting chickens of north India. Infect. Genet. Evol.. 2015;36:262-267.

- [Google Scholar]

- POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol.. 2015;6:1110-1116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Levine, N.D., 1970. Taxonomy of the sporozoa. J. Parasitol. 56 (4, sect. 2, Part 1: Supplement: Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Parasitology), pp. 208-209.

- The Coccidian Parasites (Protozoa, Sporozoa) of Rodents. Illinois Biological Monographs. 1965;33:365.

- The Coccidian Parasites of Rodents ((1st ed.).). CRC Press; 1990. p. :236p.

- Inter- and intra-strain variation and PCR detection of the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS-1) sequences of Australian isolates of Eimeria species from chickens. Vet. Parasitol.. 2003;112(1-2):33-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the second internal transcribed spacer of ribosomal DNA for three species of Eimeria from chickens in Taiwan. Vet. J.. 2007;173(1):184-189.

- [Google Scholar]

- A guide to laboratory techniques used in the study and diagnosis of avian coccidiosis. Folia Vet. Lat.. 1976;6:201-217.

- [Google Scholar]

- Time of day, age and feeding habits influence coccidian oocyst shedding in wild passerines. Int. J. Parasitol.. 2007;37(5):559-564.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overview of poultry Eimeria life cycle and host-parasite interactions. Front. Vet. Sci.. 2020;7:384.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fisheries and Food, Reference Book, Manual of Veterinary Parasitological Laboratory Techniques. Vol vol. 418. HMSO, London: Ministry of Agriculture; 1986.

- Three new species of coccidia (Sporozoa: Eimeriidae) Bull. Iraq Nat. Hist. Mus.. 1975;6:1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eimeria idmii sp-n (Apicomplexa, Eimeriidae) from the Arabian mountain gazelle, Gazella gazella, in Saudi Arabia. PHSWA. 1992;59:120-124.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel coccidian (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from Scotophilus leucogaster (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in southern Saudi Arabia. Parasitol. Res.. 2020;119(11):3845-3852.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of the Apicomplexa: where are we now? Trends Parasitol.. 2009;25(8):375-382.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA barcoding identifies Eimeria species and contributes to the phylogenetic of coccidian parasites (Eimeriorina, Apicomplexa, Alveolata) Int. J. Parasitol.. 2011;41(8):843-850.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenies based on combined mitochondrial and nuclear sequences conflict with morphologically defined genera in the eimeriid coccidia (Apicomplexa) Int. J. Parasitol.. 2018;48(1):59-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Targeting single nucleotide polymorphism in the 18S rRNA gene to differentiate Cyclospora species from Eimeria species by multiplex PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2003;69(8):4806-4813.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eimeria trichosuri: phylogenetic position of a marsupial coccidium, based on 18S rDNA sequences. Exp. Parasitol.. 2009;122(2):165-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Note sur quelques espfeces de coccidies encore peu ftudiees. Bull. Soc. Zool. France. 1891;16:246-250.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of four murine Eimeria species in immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. J. Parasitol.. 1996;82:255-262.

- [Google Scholar]

- Purification of Eimeria sporozoites by DE-52 anion exchange chromatography. J. Protozool.. 1984;31:181-183.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early development of Eimeria papillata (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) in the mouse. J. Protozool.. 1991;38(1):53-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eimeria tenella: characterization of a 5S ribosomal RNA repeat unit and its use as a species-specific probe. Exp. Parasitol.. 1993;76(1):68-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differential diagnosis of five avian Eimeria species by polymerase chain reaction using primers derived from the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS-1) sequence. Vet. Parasitol.. 2003;117(3):221-227.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic diversity and drug sensitivity studies on Eimeria tenella field isolates from Hubei Province of China. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:137-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res.. 1994;22(22):4673-4680.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA polymorphism of srRNA gene among Eimeria tenella starins isolated in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci.. 1999;61:1331-1333.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cross-transmission studies with Eimeria arizonensis-like oocysts (Apicomplexa) in New World rodents of the genera Baiomys, Neotoma, Onychomys, Peromyscus and Reithrodontomys (Muridae) J. Parasitol.. 1992;78:406-413.

- [Google Scholar]

- Materials on the life cycle of Eimeria kriygsmanni and examination of oocysts resembling those of E. hindlei, parasites of Mus musculus. Prog. Protozool.. 1973;4:422.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantification of the crowding effect during infections with the seven Eimeria species of the domesticated fowl: its importance for experimental designs and the production of oocyst stocks. Int. J. Parasitol.. 2001;31(10):1056-1069.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single-strand restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the second internal transcribed spacer (ribosomal DNA) for six species of Eimeria from chickens in Australia. Int. J. Parasitol.. 2000;30(9):1019-1023.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic position of Eimeria antrozoi, a bat coccidium (Apicomplexa, Eimeriidae), and its relationship to morphologically similar Eimeria spp. from bats and rodents based on nuclear 18S and plastid 23S rDNA gene sequences. J. Parasitol.. 2001;87:1120-1123.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic relationships among rodent Eimeria species determined by plastid ORF470 and nuclear 18S rDNA sequences. Int. J. Parasitol.. 2001;31(7):715-719.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simple method of DNA extraction for Eimeria species. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2001;44(2):131-137.

- [Google Scholar]