Translate this page into:

Morphological and molecular analyses of Paropecoelus saudiae sp. nov. (Plagiorchiida: Opecoelidae), a trematoda parasite of Parupeneus rubescens (Mullidae) from the Arabian Gulf

⁎Corresponding author at: Zoology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. rabdelgaber.c@ksu.edu.sa (Rewaida Abdel-Gaber)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The Rosy Goatfish (Parupeneus rubescens) is considered to be one of the most common goatfish species in the Arabian Gulf used as seafood on Saudi Arabia’s fish markets. The purpose of this study was therefore to investigate one of the digenean species that infects this species of fish. It has been established that a new plagiorchiid species depends primarily on its morphological and morphometric characteristics within the Opecoelidae family and is classified as Paropecoelus saudiae referring to its host’s location. The present opecoelid species is characterized by having all the generic features within the genus Paropecoelus at morphological and morphometric levels. It could be differentiated from other species within this genus by the proportions of the different body parts, ratios of forebody/hindbody and oral/ventral suckers, location of oral sucker, number of marginal papillae on the ventral sucker, location and number of ovarian lobes, distribution and arrangement of uterine coils, extent of vitelline follicles, shape of seminal vesicle, and the terminal position of the genital pore. Due to the presence of some difficulties in the morphology of the closely related Paropecoelus species, the 18S and 28S rRNA gene-based molecular phylogenetic analysis was selected and analyzed to investigate the phylogenetic affinities and the taxonomic status of the recovered parasite species. The existing Paropecoelus species’ phylogenetic tree revealed a well-resolved distinct clade with other species belonging to The Opecoelidae family and deeply embedded within the Paropecoelus genus. The current study of the Paropecoelus species therefore reflects the third account of this genus as endoparasites of various species of the rosy goatfish.

Keywords

Paropecoelus spp.

Opecoelidae

Plagiorchiida

Arabian Gulf

1 Introduction

The Opecoelidae Ozaki, 1925 is the largest digenean family with more than 90 genera and almost 900 species, located almost exclusively in the digestive tract of marine and freshwater fish (Bray et al., 2016). Cribb (2005a) reported that the “Opecoelidae subfamily level classification is complex and unsatisfactory”. Four subfamilies are currently known: the Opecoelinae Ozaki, 1925, the Plagioporinae Manter, 1947, the Stenakrinae Yamaguti, 1970 and the Opecoelininae Gibson and Bray, 1984. The characters of the male terminal genitalia and the female proximal genitalia differentiate these taxa. The Opecoelinae and Opecoelininae, characterized by a reduced or absent cirrus-sac, are distinguished by the seminal canalicular receptacle found only in the Stenakrinae subfamily. The Plagioporinae and Stenakrinae share well-developed and muscular cirrus-sacs, differentiated in the former by the presence of a seminal canalicular receptacle. The family Opistholebetidae Fukui, 1929 was considered close to the Opecoelidae and was believed likely to be embedded within the Opecoelidae (Cribb, 2005b). In the Opecoelidae family, there are several genera that are quite large, i.e. Podocotyle Dujardin, 1845 (with 55 species), Plagioporus Stafford, 1904 (with 55 species), Coitocaecum Nicoll, 1915 (with 50 species), Opecoelus Ozaki, 1925 (with 43 species), Opegaster Ozaki, 1928 (with 37 species), Pseudopecoelus von Wicklen, 1946 (with 37 species), Neolebouria Gibson, 1976 (with 25 species), and Macvicaria Gibson and Bray, 1982 (with 51 species). The features of these genera are weak and homoplastic, and their demarcation and validity are therefore constantly being discussed and disagreed (Bray et al., 2016).

The Paropecoelus is a genus of trematodes proposed by Pritchard (1966) in the Opecoelidae subfamily. Twenty species have been reported from marine fish belonging to this genus. According to Rohner and Cribb (2013), the species belonging to this genus are readily differentiated by the number of marginal papillae on the ventral sucker, the proportions of the body, the extent of vitelline follicles, and the position of genital pore. All the species described of this genus are included in three groups based mainly on the number of papillae on the ventral sucker, were: (1) Species lacks many details including the number of papillae on the ventral sucker (i.e. Paropecoelus theraponi), (2) Species with 8 marginal papillae (i.e. Paropecoelus dollfusi, Paropecoelus indicus, Paropecoelus overstreeti, Paropecoelus sciaeni), Paropecoelus indicus is distinct in having lobed gonads, the vitellarium of Paropecoelus sciaeni is interrupted opposite the gonads, and (3) Species with 16 marginal papillae (i.e. Paropecoelus pritchardae).

DNA sequences have been used successfully in several classes of digeneans over the past few years as a data source for phylogenetic reconstruction (Tkach et al., 1999, 2000, 2001). Based on the partial sequences of the nuclear LSU ribosomal DNA (lsrDNA) gene, phylogenetic relationships of a number of genera and families belonging to the Plagiorchiata suborder were recently examined (Tkach et al., 2000, 2001; Parker et al., 2010; Razo-Mendivil and Pérez-Ponce de León, 2011). Molecular studies have begun to clarify the complexity of Opecoelidae family, but no clear pattern has yet emerged (Bray et al., 2016).

Obviously, more comprehensive work is needed to get a better idea of the parasitic infections of the Arabian Gulf fish in general and those of Saudi Arabia in particular. This study is therefore aimed at providing full data on parasitic trematodes and their indices in the rosy goatfish Parupeneus rubescens from the Arabian Gulf in Saudi Arabia.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Fish collection and parasitological studies

The rosy goatfish Parupeneus rubescens (n = 20) were collected from the Arabian Gulf, Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. Fish were brought to the Laboratory for macro- and microscopic examination. Internal organs were examined for searching of parasite infections under a stereo-dissecting microscope, and their prevalence was estimated regarding to the equation of Bush et al. (1997). The recovered trematodes were fixed in a buffered formalin solution (10%), then stained with Semichon's acetocarmine, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared in clove oil and mounted in permanent preparations with Canada balsam. A Leica DM 2500 microscope (NIS ELEMENTS software, ver. 3.8) was used to analyze and photograph the stained specimens. All measurements in the descriptions and tables are in millimeters and presented as the range followed by the mean ± standard deviation in parentheses.

2.2 Molecular analysis

According to the manufacturer’s, genomic DNA was extracted from ethanol-preserved samples using a DNeasy tissue kit© (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). According to the manufacturer’s protocol, the nuclear 18S and 28S rRNA genes were amplified using GeneJETTM PCR Purification kit [Thermo (Fermentas)] and the following primers for 18S rRNA gene were 18SU467F (5′-ATC CAA GGA AGG CAG CAG GC-3′) as mentioned previously by Nowrousian et al. (2005) and 18SL1170R (5′-GTG CCC TTC CGT CAA TTC CT-3′), as designed by Indartanto et al. (2015), and for 28S rRNA gene were JB10F (5′-GAT TAC CCG CTG AAC TTA AGC ATA-3′) and JB9R (5′-GCT GCA TTC ACA AAC ACC CCG ACT C-3′), as designed by Lee et al. (2007). The cyclic conditions were as follows: 5 min for initial denaturing cycle at 95 °C, 30 sec 94 °C for 35 cycles of DNA denaturation, 30 sec primer annealing at 60 °C (for 18S rRNA) and 65 °C (for 28S rRNA), 2 min extension at 72 °C, and a final extension for 7 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified and sequenced using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on a 310 Automated DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A BLAST search was conducted on the NCBI database to identify similar sequences. The sequences obtained were aligned using multiple sequence alignment CLUSTAL-X. A dendrogram formed on the basis of the Kimura 2-parameter model and Jukes-Cantor model using MEGA 7.0 by Maximum Likelihood method. Tree was drawn to scale and branch support values were estimated with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

3 Results

Fifteen out of twenty (75%) specimens of the examined rosy goatfish Parupeneus rubescens were found to be naturally infected by a trematode parasite that was known in the intestine of infected fish as Paropecoelus saudiae sp. Nov.

3.1 Microscopic examination (Figs. 1 and 2, Table 1)

Body sub-cylindrical to fusiform, flattened, blunt-pointed at extremities, 2.220–3.456 (2.276 ± 0.1) mm long by 0.201–0.298 (0.264 ± 0.01) mm as a maximum width as the level of ventral sucker. Cuticle apparently smooth. Forebody short, 0.231–0.287 (0.254 ± 0.01) mm, narrower than hindbody. Oral sucker subterminal ventral, 0.074–0.087 (0.079 ± 0.001) × 0.071–0.085 (0.081 ± 0.001) mm. Prepharynx short, 0.18–0.29 (0.21 ± 0.01) mm long; pharynx barrel-shaped, 0.052–0.064 (0.059 ± 0.001) mm in diameter; esophagus short, 0.072–0.113 (0.104 ± 0.01) mm long, thin walled, bifurcating in front of the base of ventral sucker; ceca united posteriorly and opening ventrally at posterior extremity of the body. Ventral sucker short stalked, 0.106–0.121 (0.118 ± 0.01) × 0.125–0.146 (0.131 ± 0.01) mm; bearing 12 papillae, including 4 at aperture (2 anterior and 2 posterior) and 8 marginal papillae in 4 groups of 2 (one each at anterior and posterior lateral margins).

Testes two, tandem, close together, both slightly lobate or anterior testis may be smooth; anterior testis 0.157–0.231 (0.218 ± 0.01) × 0.114–0.165 (0.143 ± 0.01) mm and displaced only slightly to left of median line, at anterior end of posterior third of the body, posterior testis 0.171–0.201 (0.197 ± 0.01) × 0.135–0.201 (0.187 ± 0.01) mm, just a little to right of median line at anterior end of posterior quarter of the body. Cirrus sac small, narrow, inconspicuous, at the level of cecal bifurcation and anterior portion of acetabular stalk, sinistral; containing muscular cirrus, pars prostatica, prostatic cells surrounding attenuated distal portion of seminal vesicle, and short, tubular seminal vesicle. External seminal vesicle sinuous, narrow, slightly over half way to ovary, not reaching vitellaria. Genital atrium small. Genital pore sinistrally sub-median, and a little prebifurcal.

Ovary 0.143–0.195 (0.175 ± 0.01) × 0.132–0.151 (0.136 ± 0.01), four lobed, pretesticular, in tandem with testes. Uterine seminal receptacle; ootype complex that dorsally overlaps the anterior portion of the ovary. Laurer's canal apparently opening dorsally just anterosinistral to the vitelline reservoir. Uterus with few coils between ovary and posterior portion of the external seminal vesicle, then ascending to metraterm with few slight undulations; latter slightly longer than cirrus sac. Eggs large, yellow, operculate, with small knob at an opercular end, and 0.042–0.055 (0.049 ± 0.001) × 0.031–0.039 (0.036 ± 0.001) mm. Vitelline follicles extending along each side of the body as far as posterior extremity, commencing on the right at the level of middle of the ventral sucker and on the left just behind genital pore. Anteriorly they are mostly confined to the extracecal fields, but posterior to the ovarian level and distribute medially across the ceca and become confluent behind the posterior testis. Vitelline reservoir situated just in front of anterodextral corner of ovary. Excretory bladder tubular, extending to ovarian region, and opened through terminal pores outside. Table 1 shows the maximum and minimum values, as well as the mean values, of the different body parts of this species in comparison to the Paropecoelus species previously described.

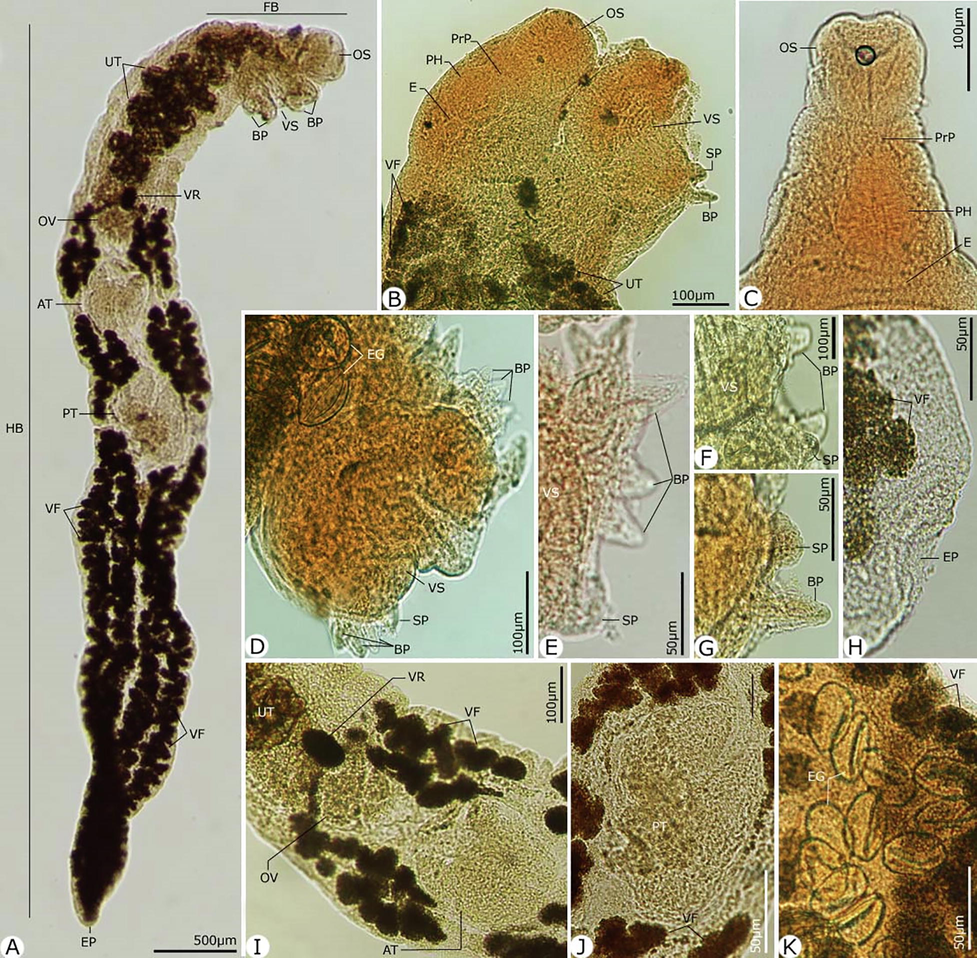

Photomicrographs of the adult Paropecoelus saudiae sp. nov. infecting Parupeneus rubescens. (A) Whole mount preparation. (B-K) High magnifications for different body parts showing: (B) Forebody region with generic features. (C) Anterior extermity. (D-G) Ventral sucker with transverse slit aperture and provided with simple and biramous papillae. (H) Excretory pore at posterior extermity. (I) Hindbody with reproductive organs. (J) Posterior testis (K) Eggs. Note: AT, Anterior testis; BP, Biramous papillae; E, Esophagus; EP, Excretory pore; FP; Forebody; HB, Hindbody; OS, Oral sucker; OV, Ovary; PH, Pharynx; PrP, Prepharynx; Pt, Posterior testis; SP, Simple papillae; UT, Uterus; VF, Vitelline follicles; VR, Vitelline reservoir; VS, Ventral sucker.

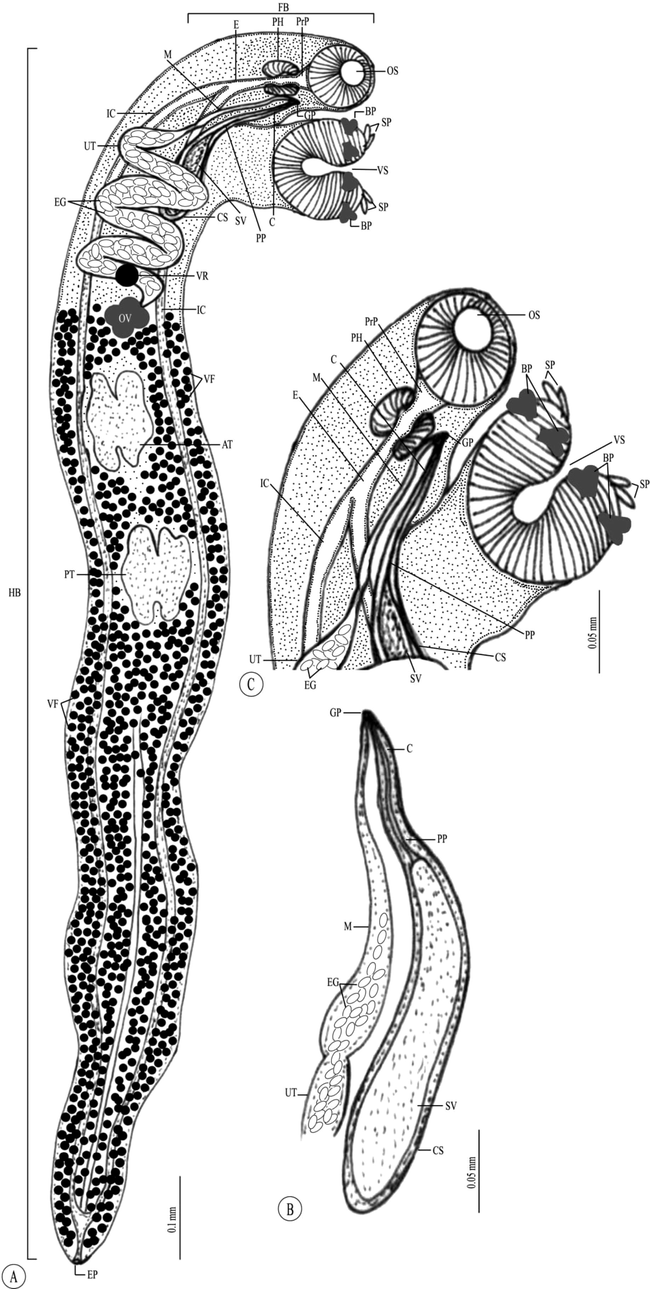

Line drawing of the adult Paropecoelus saudiae sp. nov. infecting Parupeneus rubescens. (A) Whole mount preparation. (B,C) High magnifications for different body parts showing: (B) Forebody. (C) Terminal genital organs. Note: AT, Anterior testis; BP, Biramous papillae; C, Cirrus; CS, Cirrus sac; E, Esophagus; EG, Eggs; EP, Excretory pore; FB, Forebody; GP, Genital pore; HB, Hindbody; IC, Intestinal ceca; M, Metraterm; OS, Oral sucker; OV, Ovary; PH, Pharynx; PP, Pars prostatica; PrP, Prepharynx; PT, Posterior testis; SP, Simple papillae; SV, Seminal vesicle; UT, Uterus; VF Vitelline follicles; VR, Vitelline reservoir; VS, Ventral sucker.

4 Remarks

For that the recovered Paropecoelus species is similar to P. elongatus P. sogandaresi, and P. overstreeti with twelve papillae on ventral sucker which larger in size than oral one; P. indicus with lobed gonads, caeca united posteriorly and opening via common ventro-terminal anus, and genital pore sinistral at mid-oesophageal level; P. dollfusi, P. corneliae, and P. leonae with anterior intestinal bifurcation of the intestine to the ventral sucker, caeca united posteriorly and opening subterminally by anus, genital pore sinistral at anterior oesophagus level, I-shaped excretory vesicle, vitellarium extending from posterior end of body to ventral sucker level, terminal excretory pore; and P. elongatus, P. corneliae, P. dollfusi, and P. indicus by having pretesticular four-lobed ovary.

However, the recovered Paropecoelus species is differ from P. indicus by ventral sucker with four biramous papillae one on each anterolateral and each postero-lateral margin and four smaller apertural papillae, multiple uterus coils in pre-ovarian area, and vitellarium extends anteriorly between ovary and ventral sucker; P. dollfusi with four uniramous papillae, rounded body extremities, terminal oral sucker with triangular opening, vitellarium extends only to the ovarian level, and seminal vesicle extends only slightly posterior to ventral sucker; P. overstreeti with four biramous peripheral papillae one on each anteriolateral and each postero-lateral margin of the ventral sucker, intestinal bifurcation at midway between pharynx and ventral sucker, post-equatorial testes, winding seminal vesicle that extends slightly posterior to ventral sucker, genital pore at the level of mid-pharynx, and post-equatorial spherical ovary. In addition, there are some distinctions P. pritchardae and P. quadratus with 16 marginal papillae on ventral sucker, entire and spherical testes, vitellarium interrupted at gonads level and extended from the anterior 1/3rd of the distance between ventral sucker and ovary and a smaller post-testicular space; P. sciaeni with eight marginal papillae on the ventral sucker, vitellarium interrupted at the gonads level; P. corneliae with testes entire and tandem in posterior half of the body, saccular seminal vesicle, genital pore in mid-forebody, and a relatively much shorter post-testicular zone; P. leonae and P. sogandaresi with a substantially larger post-testicular field, twenty papillae on ventral sucker (4 aperture and 16 marginal ones), intestinal bifurcation in posterior forebody, and genital pore located in mid-forebody; P. elongatus and P. corneliae have a spherical to sub-spherical pharynx, and a dextral genital pore; and P. elongatus, P. leonae, and P. dollfusi with 4-lobed testes in posterior half of the body, and uterine coils restricted in the area between ovary and genital pore.

Parameters

Host species (Locality)

Body size

Measurements of different body parts

No. of ventral sucker papillae

Forebody

Oral sucker

Ventral sucker

Anterior testis

Posterior testis

Ovary

Eggs

P. elongatusOzaki (1928)

Parupeneus ciliatus (Australia)

1.522–3.245 (2.287) × 0.141–0.563 (0.309)

0.141–0.365 (0.265)

0.045–0.112 (0.085) × 0.045–0.108 (0.087)

0.115–0.252 (0.169) × 0.121–0.214 (0.170)

0.112–0.242 (0.167) × 0.057–0.201 (0.142)

0.083–0.268 (0.191) × 0.077–0.207 (0.146)

0.070–0.182 (0.109) × 0.061–0.175 (0.114)

0.038–0.061 (0.047) × 0.019–0.032 (0.024)

Twelve papillae (4 aperture + 8 marginal)

P. sogandaresiPritchard (1966)

Parupeneus ciliatus (Australia)

2.127–3.201 (2.848) × 0.158–0.381 (0.291)

0.353–0.435 (0.391)

0.100–0.121 (0.111) × 0.108–0.139 (0.125)

0.171–0.225 (0.197) × 0.187–0.232 (0.209)

0.0272–0.403 (0.331) × 0.139–0.216 (0.179)

0.278–0.495 (0.389) × 0.139–0.229 (0.180)

0.148–0.196 (0.167) × 0.097–0.142 (0.120)

0.047–0.052 (0.049) × 0.030–0.037 (0.034)

Twenty papilae (4 aperture + 16 marginal)

P. indicusHafeezullah (1970)

Parupeneus indicus (Tuticorin)

4.512–5.82 × 0.288–0.42

–

0.084–0.119 × 0.091–0.098

0.149–0.19 × 0.158–0.197

0.33–0.414 × 0.193–0.266

0.33–0.414 × 0.193–0.266

–

0.030–0.042 × 0.021–0.033

Four pairs of biramus peripheral papillae

P. overstreetiAhmad (1983)

Terapon theraps (India)

2.200–2.300 × 0.279–0.312

–

0.105–0.128

0.127–0.150

–

–

–

0.049–0.058 × 0.034–0.038

Four biramous papillae

P. dollfusiAhmad (1983)

Upeneus sulphureus (India)

1.915–2.322 × 0.287–0.322

–

0.068–0.092

0.112–0.140 × 0.135–0.168

–

–

–

0.040–0.050 × 0.028–0.035

Four uniramous papillae

P. corneliaeRohner and Cribb (2013)

Parupeneus ciliatus (Australia)

1.323–2.551 (1.784) × 0.160–0.384 (0.271)

0.284–0.493 (0.347)

0.069–0.131 (0.101) × 0.083–0.117 (0.103)

0.145–0.211 (0.167) × 0.164–0.175 (0.172)

0.132–0.284 (0.192) × 0.103–0.221 (0.152)

0.140–0.386 (0.242) × 0.109–0.230 (0.163)

0.085–0.220 (0.134) × 0.073–0.187 (0.128)

0.041–0.064 (0.059) × 0.019–0.035 (0.026)

Twelve papillae (4 apeture + 8 marginal)

P. leonaeRohner and Cribb (2013)

Parupeneus ciliatus (Australia)

1.402–3.086 (2.052) × 0.185–0.459 (0.292)

0.184–0.268 (0.212)

0.048–0.080 (0.068) × 0.064–0.082 (0.073)

0.131–0.188 (0.163) × 0.112–0.173 (0.146)

0.077–0.242 (0.157) × 0.057–0.201 (0.132)

0.083–0.268 (0.175) × 0.077–0.207 (0.141)

0.061–0.148 (0.097) × 0.054–0.153 (0.105)

0.043–0.052 (0.049) × 0.025–0.032 (0.029)

Twenty papillae (4 groups of 4)

P. saudiae sp. nov. Present study

Parupeneus rubescens (Saudi Arabia)

2.220–3.456 (2.276 ± 0.1) × 0.201–0.298 (0.264 ± 0.01)

0.231–0.287 (0.254 ± 0.01)

0.074–0.087 (0.079 ± 0.001) × 0.071–0.085 (0.081 ± 0.001)

0.106–0.121 (0.118 ± 0.01) × 0.125–0.146 (0.131 ± 0.01)

0.157–0.231 (0.218 ± 0.01) × 0.114–0.165 (0.143 ± 0.01)

0.171–0.201 (0.197 ± 0.01) × 0.135–0.201 (0.187 ± 0.01)

0.143–0.195 (0.175 ± 0.01) × 0.132–0.151 (0.136 ± 0.01)

0.042–0.055 (0.049 ± 0.001) × 0.031–0.039 (0.036 ± 0.001)

Twelve papillae (4 aperture + 8 marginal)

5 Molecular analysis

5.1 For 18S rRNA gene region

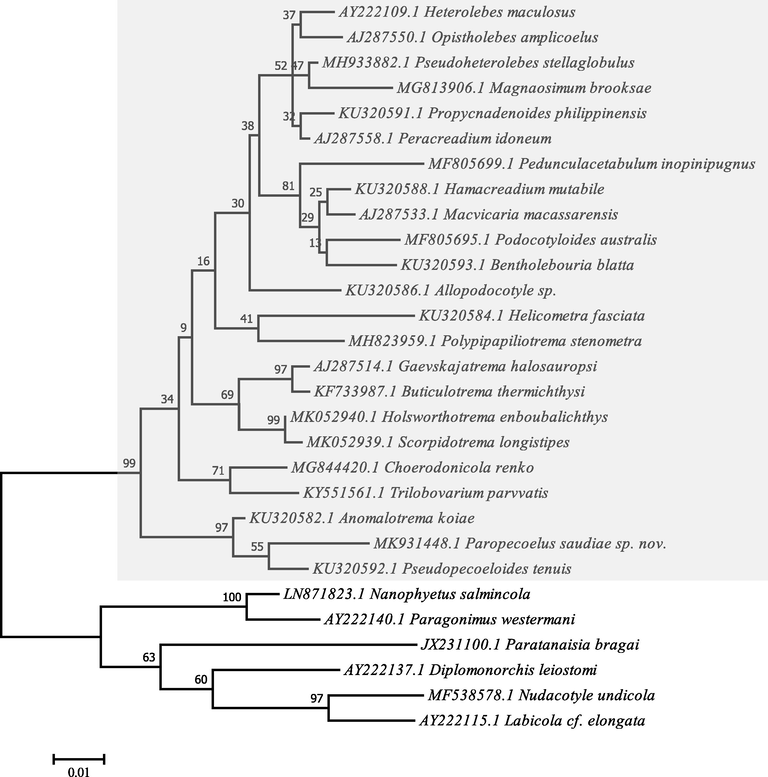

A total of 615 bp with a GC content of 49.26% was analysed and the resulting sequences were deposited in GenBank for the 18S rRNA gene region of the present digenea species under the accession number MK931448.1. No identical sequences could be found in the DNA databases through the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST). Phylogenetic analysis was performed on the basis of a comparison with 28 related species using maximum likelihood method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model representing order Plagiorchiida (Fig. 3).

Molecular Phylogenetic analysis by Maximum Likelihood method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-3063.38) is shown. The percentage of trees is shown above the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.

Comparison of nucleotide sequences and divergence showed that the 18S rRNA of this species reported gene identities with taxa belonging to Plagiorchiida as 97.08–94.04% with Xiphidiata, 90.22–89.21% with Troglotremata, 89.34% with Echinostomata, 89.28% with Monorchiata, and 89.26–89.22% with Pronocephalata. The maximum identity with lowest divergent values were recorded with other opecoelid species, Pseudopecoeloides tenuis (97.08%, gb| KU320592.1), Anomalotrema koiae (96.92%, gb| KU320582.1), Choerodonicola renko (94.66%, gb| MG844420.1), Holsworthotrema enboubalichthys (94.50%, gb| MK052940.1), Propycnadenoides philippinensis (94.50%, gb| KU320591.1), Gaevskajatrema halosauropsi (94.49%, gb| AJ287514.1), Trilobovarium parvvatis (94.34%, gb| KY551561.1), Buticulotrema thermichthysi (94.17%, gb| KF733987.1), Scorpidotrema longistipes (94.01%, gb| MK052939.1), Hamacreadium mutabile (94.01%, gb| KU320588.1), and Heterolebes maculosus (94.01%, gb| AY222109.1).

The constructed dendrogram is divided into two clades, the major one clustering of opecoelid species within Xiphidiata. This clade is divided into three lineages representing two families Opecoelidae and Opistholebetidae, within Allocreadioidea, the first lineage clustered three genera Anomalotrema that forming sister groups with very strong nodal support to Paropecoelus and Pseudopecoeloides; the second lineage clustered Gaevskajatrema, Buticulotrema, Holsworthotrema, and Scorpidotrema with strong nodal support; and the third lineage consisted of Helicometra, Choerodonicola, Podocotyloides, Propycnadenoides, Hamacreadium, Trilobovarium, Allopodocotyle, Pseudoheterolebes, Magnaosimum, Macvivaria, Paracreadium, Pedunculacetabulum, Bentholebouria, Polypipapiliotrema, and Heterolebes with weak nodal support; the latter genus forming sister group to Opistholebes within Opistholebetidae. While, the minor clade subdivided into four lineages; the former one clustered all species belonging to Troglotremata, Echinostomata, Monorchiata, and Pronocephalata; the latter lineage indicated the basal position within Plagiorchiida. Eucotylidae forming sister group to Nanophyetidae + Troglotrematidae. Monorchiidae forming sister group to Nudacotylidae + Labicolidae. The ME tree revealed a well-resolved distinct clade for the present plagiorchiid species with other members of the digenea species belonging to the Opecoelidae family and deeply embedded in the Paropecoelus genus with close relationship to Pseudopecoeloides tenuis (gb| KF733988.1) and Anomalotrema koiae (gb| KU320582.1) as a more related sister taxons.

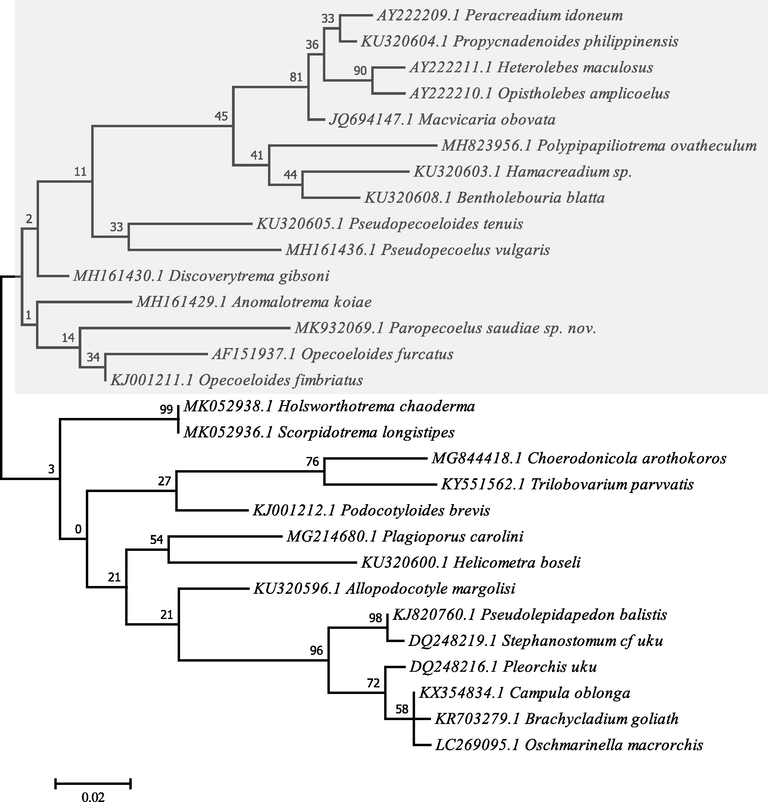

5.2 For 28S rRNA gene region

A total of 238 bp with 57.98% GC content was analysed and the resulting sequences of the present digenea species were deposited in GenBank under the accession number MK932069.1 for 28S rRNA gene region. The basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) could not found similar sequences in DNA databases. Phylogenetic analyses were carried out on the basis of a comparison with 28 related species using maximum likelihood method based on the Jukes-Cantor model representing two orders Plagiorchiida and Opisthorchiida (Fig. 4).

Molecular Phylogenetic analysis by Maximum Likelihood method based on the Jukes-Cantor model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-1534.35) is shown. The percentage of trees is shown above the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying the Maximum Parsimony method. The tree is drawn to scale. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.

Comparison of nucleotide sequences and divergence showed that the 28S rRNA of this species revealed sequence identities with taxa belonged to Plagiorchiida as 94.51–88.19% with Opecoelidae, and 88.74–88.19% with Brachycladiidae. While, the gene identities for Opisthorchiida nucleotide sequences were 89.03–88.61% with Acanthocolpidae family’s taxa. With other opecoelid species, the maximum identity with lowest divergent values were recorded for Opecoeloides fimbriatus (94.51%, gb| KJ001211.1), Discoverytrema gibsoni (93.67%, gb| MH161430.1), Anomalotrema koiae (92.83%, gb| MH161429.1), Opecoeloides furcatus (92.07%, gb| AF151937.1), Holsworthotrema chaoderma (91.98%, gb| MK052938.1), Scorpido-trema longistipes (91.98%, gb| MK052936.1), Pseudopecoeloides tenuis (90.72%, gb| KU320605.1), Podocotyloides brevis (90.72%, gb| KJ001212.1), and Pseudopecoelus vulgaris (90.13%, gb| MH161436.1).

The constructed dendrogram is divided into two clades, the major one clustered some opecoelid species within Xiphidiata. This clade is divided into two lineages, three genera clustered in the first within Opecoelidae were Anomalotrema forming sister groups to Paropecoelus and opecoeloides; while, the second lineage of Opecoelidae consisted of nine genera were Discoverytrema, Pseudopecoelus, Pseudopecoeloides, Bentholebouria, Hamacreadium, Polypipapiliotrema, Heterolebes, and Propycnadenoides, Peracreadium. The minor clade, however, subdivided into two lineages; the former clustered the remaining genera within Opecoelidae were Holsworthotrema, Scorpidotrema, Choerodonicola, Trilobovarium, Podocotyloides, Plagioporus, Helicometra, and Allopodocotyle; while, the latter lineage clustered taxa with very strong nodal support within the Brachycladiidae family that is forming sister group to Acanthocolpidae within Opisthorchiida. For the present plagiorchiid species, the ME tree revealed a well-resolved distinct clade with other members of the digenea species belonging to the Opecoelidae family and deeply embedded in the genus Paropecoelus with close relationship to Opecoeloides furcatus (gb| AF151937.1), Opecoeloides fimbriatus (gb| KJ001211.1), and Anomalotrema koiae (gb| MH161430.1) as a more related sister taxons.

6 Discussion

The Paropecoelus, including about 20 species, is a genus of trematodes in Opecoelinae subfamily within the Opecoelidae family. The intestinal region is considered as a host site preference for members belonging to Opecoelidae family (Cribb, 2005a; Shimazu, 2016), this agreed with our observation. The current study showed a high value (75%) for parasitic prevalence of the recovered opecoelid species. However, it is higher than opecoelid species infecting nine species of mullids from Lizard Island (45.3%, Rohner and Cribb, 2013). Crowcroft (1945) also recorded a lower prevalence rate for Coitocaecum parvum infecting Galazias attenuatus from Near Bower Monument in East Risdon near Hobart (1–6%), and Opecoelus tasmanicus infecting Latridopsis forsteri from Hobart Fish Market (8%). This prevalence of all opecoelid species reported by Manter (1940) is also as follows: Opecoelus xenistii infecting Xenistius californiensis from Tagus Cove, Albemarle Island, Galapagos (7%); Opegaster acuta infecting Abudefduf saxatalis from Socorro Island, Mexico (12%); Opegaster pentedactyla infecting Balistes verres from Charles Island, Galapagos (4%); Opegaster parapristipomatis infecting Trachinotus rhodopus from Chatham Island, Galapagos (6%); Opecoelina pacifica infecting Paralabrax sp. from Albemarle Island, Galapagos (15%); and Coitocaecum tropicum infecting Bathygobius soporator from Charles Island, Galapagos (6%). However, it is lower than the rate observed for Opegaster ouemoensis infecting Periophthalmus argentilineatus Valenciennes in the mangroves of New Caledonia (93%, Bray and Justine, 2013).

At morphological and morphometric levels, the present opecoelid species is compatible with other species of Paropecoelus by possessing all the characteristic features but with some exceptions. The current study of the Paropecoelus species reflects the third account of this genus as endoparasites of various species of the rosy goatfish. Twenty species belonging to this genus could be distinguished from each other by the number of marginal papillae on the ventral sucker, the proportions of the body, the extent of vitelline follicles and the position of genital pore. The recovered parasite was compared with different Paropecoelus species inhabiting different hosts in many geographical localities and revealed that the present species was more or less different from all comparable ones. In addition, it showed some similarties to P. elongates, P. sogandaresi, P. indicus, P. dollfusi, P. overstreeti, P. corneliae, P. leonae, as mentioned above. While, it presented many differences from others as P. indicus, P. dollfusi, P. overstreeti, P. pritchardae, P. sciaeni, P. corneliae, P. leonae, P. sogandaresi, P. elongates, P. sogandaresi, P. quadratus, as mentioned above. Therefore at both the morphological and morphometric levels, it could be identified as P. saudiae sp. nov.

DNA sequences have been used successfully in several groups of digeneans over the past few years as a data source for phylogenetic reconstruction (Tkach et al., 1999). Based on the partial sequences of the nuclear LSU ribosomal DNA (lsrDNA) gene, phylogenetic relationships of a number of genera and families belonging to the order Plagiorchiida were recently examined (Tkach et al., 2000, 2001). In the present study, we used the combination of data from two nuclear ribosomal RNA (18S and 28S) genes to examine phylogenetic affinities and taxonomic status of the recovered opecoelid species. The current topology resulting from maximum parsimony analyses showed that Plagiorchiida represented by one suborder consisting of three families within Allocreadioidea: Xiphidiata including Opecoelidae, Opistholebetidae, and Brachycladiidae; two suborders with two families: Troglotremata including Nanophyetidae and Troglotrematidae, Pronocephalata including Nudacotylidae and Labicolidae; two suborders with one family for each: Echinostomata including Eucotylidae, Monorchiata including Monorchiidae. These results agreed with data obtained by Olson et al. (2003). Herein, the origin of Plagiorchiida is a monophyly, agreed with Pérez-Ponce de León and Hernández-Mena (2019) who believed that Diplostomida and Plagiorchiida were two well-known and widely accepted orders within Digenea and recovered as monophyletic groups with high bootstrap support for the ML analysis.

The Acanthocolpidae within Opisthorchiida, represented by Stephanostomum cf uku, Pseudolepidapedon balistis and Pleorchis uku, was found to be polyphyletic, with Camoula oblonga, Brachycladium goliath, and Oschmarinella macrorchis grouping together with the Brachycladiidae with strong nodal support; this data is consistent with Olson et al. (2003). Fernández et al. (1998a,b) reported that Opecoelidae + Opistholebetidae and Acanthocolpidae are exclusively parasites of fish and the Brachycladiidae are from marine mammals. Littlewood et al. (2015) reported that Acanthocolpidae in the Allocreadioidea as sister group to Brachycladiidae, as described herein.

In addition, the present study showed that Opecoelidae is paraphyletic, as it is consistent with Cribb (2005a) whom considered that the classification of subfamily level within Opecoelidae is complex and unsatisfactory. In addition, Cribb (2005a) recognized four subfamilies within this family as mentioned herein. The present study showed a close relationship between Opecoelidae and Opistholebetidae, as consistent with Cribb (2005b) who reported that family Opistholebetidae Fukui, 1929 was considered close to Opecoelidae and was thought likely to be integrated into Opecoelidae. Our topology clearly places the genus Helicometra with moderate support value as a sister group to Opecoelinae and Plagioporinae, which was accepted with Nolan and Cribb (2005) who reported that the sequences of nuclear ribosomal RNA genes are obviously more useful for species differentiation than higher phylogeny.

In addition, the nesting of two opistholebetids, Heterolebes maculosus and Opistholebes amplicoelus, within a clade of plagioporines with a weak nodal support which possess a taxonomic challenge, as stated by Cribb (2005b) who assumed that nesting as both of them had similar morphological features except for the first one by having the posterior position of the ventral sucker, the presence of a post-oral ring, the presence of pigment granules and the parasitism in diodontid and tetraodontid fish.

The current topology showed the upnormal occurrence of Allopodocotyle margolisi with low support nodal value, as mentioned by Gibson (1995), Lucas et al. (2005), Kellermanns et al. (2009), Blend et al. (2015), and Bray et al. (2016) who recorded this occurrence indicating that some convergence appears to have occurred. In addition, it is nested with strong nodal support value in the clade including Gaevskajatrema halosauropsi and Buticulotrema thermichthysi, according to the possible explanation by Bray et al. (2014) who indicated that the possible reason for this arrangement in the current topology is regarding to the morphological features such as the missing cirrus-sac and the presence of saccular seminal receptacle.

In the present study, the sister to Hamacreadium mutabile is Macvicaria macassarensis and Bentholebouria blatta with a high nodal support value, which all of them from Lethrinus spp., this result agreed with Bray and Cribb (1989), Cribb (2005a), Born-Torrijos et al. (2012), Justine et al. (2012), Antar et al. (2015), and Bray et al. (2016) whom stated that Hamacreadium sp. is placed in Macvicaria based on some morphological generic features as the entire, rather than lobed ovary, excretory vesicle reached to posterior edge of ventral sucker. Herein, dendrogram showed monophyly of Peracreadium idoneum, Propycnadenoides philippinensis and Gaevskajatrema perezi with low nodal support, as described by Bray et al. (2016) who given a possible explanation that all of them are fairly typical plagioporines.

Furthermore, the clustering of Holsworthotrema enboubalichthys and Scorpidotrema longistipes among Opecoelidae is very important, as these taxa are the only opecoelid genera of herbivorous fish and only opecoelids known infecting Kyphosus gladius and Scorpis georgiana, and also likely endemic to southern Australian waters, as mentioned by Martin et al. (2019). Both Holsworthotrema enboubalichthys and Scorpidotrema longistipes are nested in the clade of Gaevskajatrema halosauropsi and Buticulotrema thermichthysi, due to the possible explanation by Cribb (2005a) and Martin et al. (2019) for the presence of two morphological characters, a well-defined cirrus-sac completely encompassing the seminal vesicle and a canalicular seminal receptacle. The current topology showed that Anomalotrema koiae forms sister taxon to Opecoeloides spp. and Pseudopecoeloides tenuis with very strong nodal support, which agreed with Bray et al. (2016) followed by Sokolov et al. (2019) stated that they all share a morphological feature of caeca opened separately ventrally to the excretory pore.

The present maximum parsimony analysis found that there is a close relationship between the present Paropecoelus sp. and Pseudopecoeloides tenuis + Opecoeloides spp., which is consistent with the observation by Rohner and Cribb (2013) that these species form a well-supported clade. As mentioned by Lo et al. (2001) and Nolan and Cribb (2006), limit information on the phylogeny of Paropecoelus is available. The present study provides clear data for the species analysed in this study in order to establish morphologically a close relationship with the previously described Paropecoelus spp. as it could be differentiated from generally opecoelid species and in particular Paropecoelus species by the number of marginal papillae on the ventral sucker, the body proportions, the extent of the vitelline follicles and the position of the genital pore. Furthermore, the molecular status for this species characterized by the presence of unique genetic sequences within the genus Paropecoelus that belonging to Opecoelidae.

Key to identification of Paropecoelus species:

Twelve papillae on ventral sucker (4 aperture and 8 marginal) .... 2

Eight papillae on ventral sucker .... P. indicus, P. sciaeni

Four uniramous papillae on ventral sucker .... P. dollfusi, P. overstreeti

Sixteen marginal papillae on ventral sucker .... P. pritchardae, P. quadratus

Ventral size larger than oral one .... 3

Ventral size similar in size to oral one .... P. indicus, P. sciaeni, P. dollfusi, P. overstreeti, P. pritchardae, P. quadratus, P. corneliae, P. leonae, P. sogandaresi

Oral sucker sub-terminally .... 4

Terminal oral sucker with triangular opening .... P. dollfusi, P. indicus, P. overstreeti

Pharynx barrel-shaped .... 5

Oval shaped pharynx .... P. indicus, P. dollfusi

Spherical to sub-spherical pharynx .... P. elongatus and P. corneliae

Anterior intestinal bifurcation to the ventral sucker .... 6

Intestinal bifurcation at midway between pharynx and ventral sucker .... P. overstreeti

Genital pore sinistral at mid-oesophageal level .... 7

Genital pore at the level of mid-pharynx .... P. overstreeti

Genital pore at anterior level of pharynx .... P. pritchardae

Pretesticular four-lobed ovary .... 8

Post-equatorial spherical ovary .... P. overstreeti

Uterus coils between ovary and cirrus sac .... 9

Multiple uterus coils in preovarian area .... P. indicus

Intercaecal uterus coils between ovary and genital pore .... P. overstreeti, P. corneliae

Vitellarium extending from posterior end of body to level of ventral sucker .... 10

Vitellarium extends to midway between ovary and ventral sucker .... P. indicus, P. pritchardae

Vitellarium extends only to the ovarian level .... P. dollfusi, P. sciaeni

Equatorial two lobate testes .... 11

Post-equatorial testes .... P. overstreeti

Entire and spherical testes .... P. pritchardae, P. corneliae

Testes distinctly 4-lobed .... P. elongatus, P. leonae, P. dollfusi

Tubular seminal vesicle extends to ovary level .... 12

Seminal vesicle extends posterior to ventral sucker .... P. dollfusi, P. overstreeti

Saccular seminal vesicle .... P. corneliae, P. elongatus, P. leonae, P. dollfusi

Caeca united posteriorly and opening via common ventro-terminal anus .... 13

I-shaped excretory vesicle extends to the level of the ovary with terminal opening .... 1

7 Conclusion

It could be assumed that valuable information on the occurrence of an opecolid species identified as Paropecoelus saudiae sp. nov. was given in the present study and having a new host species and locality records in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, it is proposed that future studies include other genes to be used to provide more knowledge of this species.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Researchers Supporting Project (RSP-2019/25), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Studies on digenetic trematodes of the family Opecoelidae Ozaki, 1925 from marine fishes of India. Rivista di Parassitologia. 1983;44:233-246.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular evidence for the existence of species complexes within Macvicaria Gibson & Bray, 1982 (Digenea: Opecoelidae) in the western Mediterranean, with descriptions of two new species. Syst. Parasitol.. 2015;91:211-229.

- [Google Scholar]

- Allopodocotyle enkaimushi n. sp. (Digenea: Opecoelidae: Plagioporinae) from the short-tail grenadier, Nezumia proxima (Gadiformes: Macrouridae), from Sagami Bay, Japan, with a key to species of this genus and a checklist of parasites reported from this host. Comp. Parasitol.. 2015;82:219-230.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular and morphological identification of larval opecoelids (Digenea: Opecoelidae) parasitising prosobranch snails in a Western Mediterranean lagoon. Parasitol. Int.. 2012;61:450-460.

- [Google Scholar]

- Digeneans of the family Opecoelidae Ozaki, 1925 from the southern Great Barrier Reef, including a new genus and three new species. J. Nat. His.. 1989;23:429-473.

- [Google Scholar]

- The molecular phylogeny of the digenean family Opecoelidae Ozaki, 1925 and the value of morphological characters, with the erection of a new subfamily. Folia Parasitol.. 2016;63:1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- A digenean parasite in a mudskipper: Opegaster ouemoensis sp. n. (Digenea: Opecoelidae) in Periophthalmus argentilineatus Valenciennes (Perciformes: Gobiidae) in the mangroves of New Caledonia. Folia Parasitol.. 2013;60:7-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- New digeneans (Opecoelidae) from hydro-thermal vent fishes in the south eastern Pacific Ocean, including one new genus and five new species. Zootaxa. 2014;3768:73-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bush, A.O., Lafferty, K.D., Lotz, J.M., Shostak, A.W., 1997. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 83, 575–583.

- Cribb, T.H., 2005a. Family Opecoelidae Ozaki, 1925. In: A. Jones, RA Bray and DI Gibson (Eds.), Keys to the Trematoda. Volume 2. CABI Publishing and the Natural History Museum, Wallingford, pp. 443–531.

- Cribb, T.H., 2005b. Family Opistholebetidae Fukui, 1929. In: A. Jones, R.A. Bray and D.I. Gibson (Eds.), Keys to the Trematoda. Volume 2. CABI Publishing and the Natural History Museum, Wallingford, pp. 533–539.

- Two new trematodes from Tasmanian fishes (Order Digenea, Family Allocreadiidae) R. Soc. Tasmania, Papers Proceed.. 1945;1944:61-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin, F., 1845. Histoire Naturelle des Helminthes ou vers Intestinaux. Librarie Encylopedie de Roret, Paris, France, pp. 654 + 15.

- Molecular phylogeny of the families Campulidae and Nasitrematidae (Trematoda) based on mtDNA sequence comparison. Int. J. Parasitol.. 1998;28:767-775.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic relationships of the family Campulidae (Trematoda) based on 18S rRNA sequences. Parasitol.. 1998;117:383-391.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on Japanese amphistomatous parasites, with revision of the group. Jap. J. Zool.. 1929;2:219-351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Allopodocotyle margolisi n. sp. (Digenea: Opecoelidae) from the deep-sea fish Coryphaenoides (Chalinura) mediterraneus in the northeastern Atlantic. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.. 1995;52:90-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study and reorganization of Plagioporus Stafford, 1904 (Digenea: Opecoelidae) and related genera, with special reference to forms from European Atlantic waters. J. Nat. Hist.. 1982;16:529-559.

- [Google Scholar]

- On Anomalotrema Zhukov, 1957, Pellamyzon Montgomery, 1957, and Opecoelina Manter, 1934 (Digenea: Opecoelidae), with a description of Anomalotrema koiae sp. nov. from North Atlantic waters. J. Nat. Hist.. 1984;18:949-964.

- [Google Scholar]

- A description of Lecithocladium angustiovum (Digenea: Hemiuridae) in Short Mackerel, Rastrelliger brachysoma (Scombridae), of Indonesia. Trop. Life Sci. Res.. 2015;26:31-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- An annotated list of fish parasites (Isopoda, Copepoda, Monogenea, Digenea, Cestoda, Nematoda) collected from snappers and bream (Lutjanidae, Nemipteridae, Caesionidae) in New Caledonia confirms high parasite biodiversity on coral reef fish. Aquat. Biosyst.. 2012;8:1-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parasite fauna of the Mediterranean grenadier Coryphaenoides mediterraneus (Giglioli, 1893) from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR) Acta Parasitol.. 2009;54:158-164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular phylogeny of parasitic Platyhelminthes based on sequences of partial 28S rDNA D1 and mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I. Korean J, Parasitol.. 2007;45:181-189.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic patterns of diversity in cestodes and trematodes. In: Morand S., Krasnov B., Littlewood D.T.J., eds. Parasite Diversity and Diversification: Evolutionary Ecology meets Phylogenetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. p. :304-319.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identical digeneans in coral reef fishes from French Polynesia and the Great Barrier Reef (Australia) demonstrated by morphology and molecules. Inter. J. Parasitol.. 2001;31:1573-1578.

- [Google Scholar]

- Digenean trematodes infecting the tropical abalone Haliotis asinina have species-specific cercarial emergence patterns that follow daily or semilunar spawning cycles. Mar. Biol.. 2005;148:285-292.

- [Google Scholar]

- Digenetic trematodes of fishes from the Galapagos Islands and the neighbouring Pacific. Rep. Allan Hancock Pacif. Exp.. 1940;2:325-497.

- [Google Scholar]

- The digenetic trematodes of marine fishes of Tortugas. Florida. Amer. Midl. Nat.. 1947;38:257-416.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new classification for deep-sea opecoelid trematodes based on the phylogenetic position of some unusual taxa from shallow-water, herbivorous fishes off south-west Australia. Zool. J. Linn. Soc.. 2019;186:385-413.

- [Google Scholar]

- A list of the trematode parasites of Bristish Marine fishes. Parasit.. 1915;7:339-378.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use and implications of ribosomal DNA sequencing for the discrimination of digenean species. Adv. Parasitol.. 2005;60:101-163.

- [Google Scholar]

- An exceptionally rich complex of Sanguinicolidae von Graff, 1907 (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda) from Siganidae, Labridae and Mullidae (Teleostei: Perciformes) from the Indo-west Pacific Region. Zootaxa. 2006;1218:1-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cross-species microarray hybridization to identify developmentally regulated genes in the filamentous fungus Sordaria macrospora. Mol. Gen. Genomics. 2005;273:137-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogeny and classification of the Digenea (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda) Inter. J. Parasitol.. 2003;33:733-755.

- [Google Scholar]

- Examination of Homalometron elongatum Manter, 1947 and description of a new congener from Eucinostomus currani Zahuranec, 1980 in the Pacific Ocean off Costa Rica. Comp. Parasitol.. 2010;77:154-163.

- [Google Scholar]

- Testing the higher-level phylogenetic classification of Digenea (Platyhelminthes, Trematoda) based on nuclear rDNA sequences before entering the age of the ‘next-generation’ Tree of Life. J. Helminthol.. 2019;93:260-276.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on digenetic trematodes of Hawaiian fishes: Family Opecoelidae Ozaki, 1925. Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik, Ökologie und Geographie der Tiere. 1966;93:173-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Testing the evolutionary and biogeographical history of Glypthelmins (Digenea: Plagiorchiida), a parasite of anurans, through a simultaneous analysis of molecular and morphological data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.. 2011;59:341-351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opecoelidae (Digenea) in northern Great Barrier Reef goatfishes (Perciformes: Mullidae) Sys. Parasitol.. 2013;84:237-253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Digeneans Parasitic in Freshwater Fishes (Osteichthyes) of Japan. IX. Opecoelidae, Opecoelinae. Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci.. 2016;42:163-180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Records of opecoeline species Pseudopecoelus cf. vulgaris and Anomalotrema koiae Gibson & Bray, 1984 (Trematoda, Opecoelidae, Opecoelinae) from fish of the North Pacific, with notes on the phylogeny of the family Opecoelidae. J. Helminthol.. 2019;93:475-485.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular and morphological evidences for close phylogenetic affinities of the genera Macrodera, Leptophallus, Metaleptophallus and Paralepoderma (Digenea, Plagiorchioidea) Acta Parasitol.. 1999;44:170-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic analysis of the suborder Plagiorchiata (Platyhelminthes Digenea) based on partial lsrDNA sequences. Int. J. Parasitol.. 2000;30:83-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular phylogeny of the suborder Plagiorchiata and its position in the system of Digenea. In: Littlewood D.T.J., Bray R.A., eds. Interrelationships of the Platyhelminthes. London: Taylor and Francis; 2001. p. :186-193.

- [Google Scholar]

- The trematode genus Opecoeloides and related genera, with a description of Opecoeloides polynemi n. sp. J. Parasitol.. 1946;32:156-163.

- [Google Scholar]

- Digenetic trematodes of Hawaiian fishes. Tokyo: Keigaku Publishing Co.; 1970. p. :436.