Translate this page into:

Morphological and genetic characterization of Fusarium oxysporum and its management using weed extracts in cotton

⁎Corresponding author. arslan.khan@mnsuam.edu.pk (Muhammad Arslan Khan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Fusarium oxysporum, a fungal plant pathogen, causes severe wilting and heavy losses in cotton. Present research was planned to appraise the weed extracts of Parthenium hysterophorus, Chenopodium album, Canada thistle and Phalaris minor against F. oxysporum. Morphological identification of F. oxysporum was done by observing white cottony mycelium with dark-purple undersurface on growth media and oval to ellipsoid/kidney shaped oval tapering and three septate spores. Molecular characterization was done by amplifying internal transcribed spacer region using the ITS universal primers, ITS1 and ITS4. The weed extract with concentrations of 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% were applied by using food poison techniques under complete randomized design. Data was taken 3, 5 and 7 days after inoculation of F. oxysporum on potato dextrose agar (PDA). P. hysterophorus showed maximum antifungal response (97%) against F. oxysporum whereas other treatments effectively inhibited the pathogen growth on PDA media. Tebuconazole, a fungicide, was used as positive control. Trichoderma harzianum showed 98% inhibition of F. oxysporum on PDA. Consortium of Trichoderma harzianum + weed extracts was applied in infected roots of cotton grown in pots under complete randomized design. No disease was observed in treatment P. hysterophorus + T. harzianum whereas maximum disease was calculated (50%) in other treatments as compared to control (100%).

Keywords

Cotton

Weed extracts

Trichoderma harzianum

Fusarium oxysporum

1 Introduction

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) is a perennial shrub and a major source of vegetable oil and natural fibers (Nix et al., 2017). It belongs to genus Gossypium and lies in family Malvaceae. China, India, United States and Pakistan are the world leading countries in cotton production. In ancient times cotton was grown near Bolan Pass, Balochistan but now Punjab and Sindh are major cotton producing provinces in Pakistan. Cotton contains about l% mineral, l% wax, l-1.5% pectic materials, 6% protein, 94% cellulose, pigments, organic acids and small amount of sugars. Cotton has obtained pivotal position in arena of scientific research and development owing to its fiscal importance (Rehman et al., 2019). It is pertinent to mention that cotton cultivators have to face many challenges concerning quality of the crop and yield including, lack of irrigation water, raising agricultural input prices such as fertilizers and pesticides, inadequacy of advanced technologies, illiteracy of farmers and insects and pests attacks in Pakistan (Sultana et al., 2013).

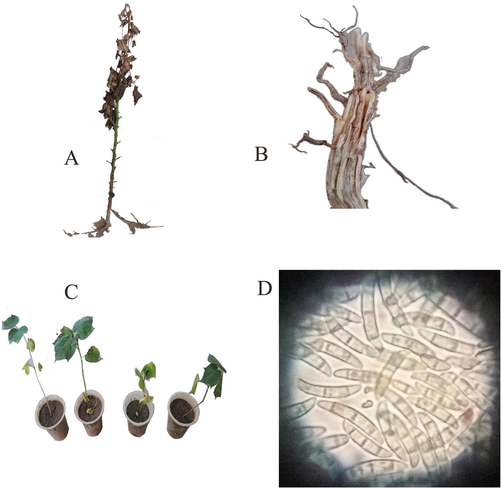

Several fungal diseases including leaf spots, black root rot (Thielaviopsis basicola), damping-off, Verticillium wilt (Verticillium dahliae), Ascochyta blight (Ascochyta gossypii), Pythium species and Rhizoctonia species are challenging for cotton growers. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (FOV), a plant pathogenic fungus, is the most devastating pathogen frequently causes severe economic losses (Cianchetta and Davis, 2015). It is both seed-borne and soil-borne, produces chlamydospores, asexual macro and micro-conidia (Akhter et al., 2016). Fungus colonizes vascular system and roots of susceptible cotton plant causes yellowing, wilting and death of plant (Fig. 1b) (Hao et al., 2009).

Pathology of Fusarium oxysporum in cotton (a) symptoms on infected cotton plant (b) Browning of root’s vascular tissue (c) yellowing of cotton plants in pathogenicity test (d) Spores of Fusarium oxysporum at 1000x.

Several strategies for the management of cotton wilt include resistant cultivars, dry heat treatment, solarization, hot water treatment, chemical fumigation, and reduction of inoculum density (Bennett and Colyer, 2010). Use of resistant cotton cultivars is the most successful approach to manage Fusarium wilt of cotton. Due to partial knowledge about genetics of resistance, breeders are unable to identify the genes and mechanism responsible for host resistance. The production of disease free seed is of great commercial interest, but contamination of cotton seed through the ball at later stages of development and unknown mechanism of seed colonization, made the task more difficult for seed companies to produced healthy seed. Although solarization, reduction of inoculum density may decrease inoculum, hot water treatment and dry heat treatment, they are often impractical to implement on a large scale (Cianchetta and Davis, 2015). The use of chemicals is an easy, approachable, effective and economical method to manage the disease for farmers. The use of synthetic pesticides is becoming more intricate due to a number of interacting factors as their injudicious use is causing severe damage to human health, non-target organisms and environment. Besides, excessive use of pesticides is resulting into failure through pest resurgence and development of heritable resistance and also contaminate the human food (Jamal et al., 2020). As a matter of fact, low discovery rate of new active molecules and consumer concerns about safety of pesticide residues in food are also a genuine concern.

Natural products are practicable solution to environmental pollution caused by synthetic pesticides whereas the research to explore the new potential natural products is being carried out by various researchers as an alternate of synthetic pesticides (Kim et al., 2005). Use of biocontrol agents amended with plant extracts for controlling plant diseases is a new integrated approach. Trichoderma spp are one of the potential fungal biocontrol agents in suppression of soil borne pathogens (Zhang et al., 2018). Use of plant extracts and beneficial microbes against diseases is the most advanced, reliable, less toxic and ecofriendly substitutes of synthetic pesticides. Importantly, they can make necessary contribution to sustainable agriculture and help reduce reliance on chemical pesticides. Plant based fungicides are non-toxic, easily biodegradable, locally available and cheap (Alam et al., 2002). Due to the ability to resist against pest and pathogens, weeds can revive much better in environment than other plants and could be the potential source of antimicrobial compounds. Several researchers have identified the antifungal and antimicrobial properties of plant species (Table 1) (Andleeb et al., 2020; Adeeyo et al., 2020). Keeping in view the economic importance of cotton wilt, presence of phytochemical constituents and antimicrobial importance of weeds present research is therefore, planned to identify the causal agent of cotton wilt and to explore the antifungal response of weeds against F. oxysporum.

Weeds

Chemical class

Major constituents

Biological activities

References

Parthenium hysterophorus

Phenolics

protocatechuic acid, ferulic acid, Caffeic acid, p-hydroxy benzoic acid, anisic acid, p-coumaric acid, chlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, neochlorogenic acid

autotoxic effect, Phytotoxic, herbicidal, growth regulator

Roy and Shaik, 2013; Abbas et al., 2013

Flavonoids

saponins, santin, lignan, luteolin, kaempferol glucoarabinoside, kaempferol glucoside, chrysoeriol, syringaresinol, quercetin glucoside, quercetagetin, dimethyl ether, apigenin, jaceidin, 6-hydroxykaempferol 3,6-dimethyl ether, 6-hydroxykaempferol-3,6,4′-trimethyl ether (tanetin), centaureidin

diuretic, antiulcerative, anticancer, antimicrobial,antioxidant,antispasmodic, antihypertensive effects, anti-inflammatory,

Roy and Shaik, 2013; Padma and Deepika, 2013

Pseudoguaianolides

anhydroparthenin, hydroxyparthenin, 11-H,13- Parthenin, dihydroisoparthenin, dihydroxyparthenin, coronopilin, 2β,13α-dimethoxydihydroparthenin, ambrosin, 13-methoxydihydroparthenin,damsin, 2β and 8β-hydroxycoronopilin, scopoletin, hysterin, hymanin, tetraneurin-A and tetraneurin-E,charminarone, 8β-acetoxyhysterone C, deacetyltetraneurin A, 1-β-hydroxyarbusculin,balchanin, costunolide, conchasin A artecanin, epoxyartemorin, 8-α-hydroxyestafiatin, 5-β-hydroxyreynosin, acetylated pseudoguaianolides, 3-β-hydroxycostunolide, hysterones A to E

Larvicidal, antiprotozoan insectidical, anti-inflammatory, inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation,antimicrobial,bioherbicidal, antineoplastic, pesticidal, cytotoxic, antimalarial

Roy and Shaik, 2013

Alkaloids

–

anti-inflammatory activities, and Antifungal, and analgesic action, antioxidant

Padma and Deepika, 2013; Kumar et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2013

Oils

eugenol, α-terpineol, α-phellandrene β-pinene, β-myrcene, α-thujene, β-ocimene, p-cymene, α-terpinene, caryophyllene, ρ-cymen-8-ol, camphor, ocimene, sabinene, humulene, limonene, chrysanthenone, terpinene-4-ol, γ-terpinene, tricylene, bornyl acetate, pinocarvone, borneol, myrtenal, caryophyllene oxide, isobornyl 2-methyl butanoate, carvacrol, germacrene, farnesene, esters, trans-myrtenol acetate, β-terpene, α-Pinene, camphene, linalool,

antimicrobial, insecticidal, helmethicidal activities, antitussive, stimulant, antispasmodic, cardiotonic, analgesic

Abbas et al., 2013; Roy and Shaik, 2013; Padma and Deepika, 2013

Chenopodium album

Flavonoids

3-O-glucopyranoside, quercetin-3-O-(2,6-di-O-R-l-rhamnopyranosyl)-beta-d- glucopyranoside,3,7-di-O-α-Lrhamnopyranoside,quercetin, kaempferol-3-O-(4-β-D-xylopyranosyl)-α-L-rhamnopyranoside-7-O-α-L-rhamno-pyranoside,3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3,7-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, rutin, 3-O-(4-β-D-apiofuranosyl)-α-L- rhamnopyranoside-7-O-α-L rhamnopyranoside

antifungal,vermifuge,anti-inflammatory, antiallergic,antiviral,antiseptic,antimicrobial anthelmintic, antiviral, antifungal, antiviral, spasmolytic, cytogenetic cytotoxic, hypotensive,

Ibrahim et al., 2007

others

hydrogen peroxide radicals, superoxide, hydroxyl, lutein, β-carotene,

–

Kumar and Kumar, 2009

Canada thistle

Compunds and essential oils

ciryneol A, cireneol G, cis-8, ciryneol H, ciryneone F, p-coumaric acid, syringin, linarin, 8,9,10-triacetoxyheptadeca-1-ene-11,13-diyne, 9-epoxy-heptadeca-1-ene-11, daucosterol, α-Humulene, E-β-Caryophyllene, β-Selinene, α-Amorphene, δ-Elemene, Camphor, ciryneol C, α-Pinene, beta-sitosterol, 1,8-Cineole, α-Bisabolol, Borneol, Oxygenated monoterpenes, 13-diyne-10-ol, methyl salicylate, 2,6-dimethyl-1,3,5,7-octatetraene, Monoterpenes, Oxygenated sesquiterpenes phenylacetaldehyde, Sesquiterpenes, dimethyl salicylate, δ-Cadinene, benzaldehyde, benzyl alcohol, methylbenzoate, linalool, pyranoid linalool oxide, benzyl benzoate, benzylacetate, 2-phenylethyl ester benzoic acid (E,E)- α-farnesene, isopropyl myristate p-anisaldehyde benzyl tiglate, phenylethyl alcohol, furanoid linalool oxide

antibacterial, antimicrobial

Dehjurian et al., 2017; El-Sayed et al., 2008

2 Material and methods

2.1 Sampling and isolation of pathogen

The symptomatic cotton plants were diagnosed and samples were collected in polythene zip bags (23 × 30 cm) from cotton growing areas of district Multan (Pakistan), kept in cooler box and placed in refrigerator at 4 °C. Samples were washed with soap and water carefully to remove soil debris and dissected lengthwise to observe vascular discoloration. Stem sections cut into 0.5–2 cm pieces with sharp cutter and immersed in 5% sodium hypochlorite solution for two minute and placed on solidified potato dextrose agar (commercially prepared: 39 g/l) wrapped in paraffin film and placed in incubator at 28 °C (dark period). Mycelial growth was observed on daily basis.

2.2 Morpho-molecular identification of pathogen

After one week of incubation, identification was done on cultural and morphological characteristics of their reproductive and vegetative structure developed on media with help of identification keys (Nelson et al., 1983). Single spore dilution method was done to obtain single spore, place on solidified media, incubated at 28 °C for 10 days at dark for pure culture and maintained on PDA in slant at 4 °C (Choi et al., 1999). The pure pathogen culture plate was shipped to Macrogen Inc. (Korea) for sequencing. The obtained sequence was compared with the sequence available in GenBank by using BLASTn server from the NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

2.3 Pathogenicity test

The pathogenicity test was performed on cotton plants (Trabelsi et al., 2017). Fusarium inoculum was obtained from 10-days-old grown media on potato dextrose agar. A mycelial plug (5 mm) from slants transferred to potato dextrose broth at 28 °C in rotary shaker at 130 rpm for 5 days. The culture was filtered from 10 layers of tissue paper and hyphae free solution was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The hard pellet containing conidia was mixed in small quantity of distilled water and supernatant was diluted in distilled water. The conidial concentration was adjusted at 3 × 106 conidia ml−1 using haemocytometer and mixed in supernatant solution. The conidial suspension was place at room temperature (25–30 °C) and used with in 1 h. Cotton seeds were grown after hot water treatment at 40–45 °C for 25 min and incubated at 27 °C for 1 day. Seeds were sown in potting soil and placed in glasshouse at 20–25 °C. The inoculation was done after three weeks of sowing. The seedlings were pull out from potting soil, washed and dipped in 100 ml beaker containing 90 ml of conidial solution for 5 min. The inoculated seedlings were transferred in pots and placed in glasshouse at 20–25 °C.

2.4 Preparation of weed extracts

Weeds were collected from research farms MNS-University of Agriculture Multan, washed with water and dried in hot oven at temperature of 60 °C for eight hours. The dried weeds were grinded well in sterilized pestle and mortar. The 5 g grinded weeds were taken in a sterilized flask and 80 ml distilled water was added. The flasks were placed in shaker at 200 rpm. After 24 h the solution was filtered from double layer muslin cloth and then passed through Whatman’s No. 1 filter paper. The extracted material was preserved in brown glass bottles at 4 °C. Food poison technique was done for the evaluation of plant extracts (PE) in full strength PDA. Mycelial plugs from Fusarium pure culture were transferred to PE-amended PDA media. Petriplates were placed in incubator at 28 °C for 7 days and colony diameter was measured two perpendicular measurements colony-1.The growth of pathogen on amended PDA media was compared with growth of pathogen on unamended PDA plates served as control. Tebuconazole, a fungicide, was also used as positive control. Mycelial growth inhibition percentage was measured using formula; I% = C − T/C × 100 (Where C = colony diameter in control, T = colony diameter in treatment, I = inhibition percentage.

2.5 Evaluation of Trichoderma harzianum against pathogen

Trichoderma harzianum taken from Plant Pathology Laboratory MNS-university of agriculture Multan was evaluated using dual culture technique with five replicates. One Mycelial agar plug (5 mm) taken from 10-days-old PDA culture from bio-control agent was placed at the periphery of PDA plate. Then another mycelial agar plug taken from 10-days-old PDA culture of Fusarium was placed at periphery of same petriplate on opposite ends. The antagonists and Fusarium were placed on fresh PDA in similar pattern as a control. The data was taken after 7 days measuring radial growth of Fusarium in direction of antagonist colony (A2) and in control (A1). Percentage inhibition of radial growth (PIRG) was measured using the formula; PIRG = A1-A2/A1x100 (Abo-Elyousr et al., 2014).

2.6 Preparation and evaluation of T. harzianum-amended weed extracts

Before mixture preparation, both, weed extracts and T. harzianum were in vitro evaluated to check any antagonistic effects of weed extracts against T. harzianum using food poison technique. The spores of T. harzianum were harvested from 10 days old PDA, mixed in weed extracts prepared at 20% concentration, stirred and stored at 4 °C. The spores were counted using heamocytometer and calculations were done using cell calculatorV2.2 software. The viability of T. harzianum spores was rechecked, after 10 days of mixture preparation, on PDA. The T. harzianum spore at 107/ml in 20% concentrated extracts of C. album, P. hysterophorus, C. thistle and P. minor were used in pot trial against F. oxysporum. The soil was sterilized and filled in pots. Ten cotton plants (variety;FH-142) for each treatment with a separate control for each treatment were maintained. A solution containing F. oxysporum spores was made from already grown pure culture and poured in 45 days old cotton plant roots. The weed extracts amended with T. harzianum were applied after 15 days of pathogen inoculation. Disease indices were recorded after 25 days of F. oxysporum inoculation. The scale was used as follows: 0, healthy plant; 1, less than 25% discolored root; 2, 25–50% discolored root; 3, 50–75% discolored root; and 4, 75–100% discolored root. The data of disease index was calculated using formula (Wang et al., 2016). The results were submitted to analysis of variance and the treatments were considered significantly different when probability was less than 5% (p ≤ 0.05). When the F-test was significant, Tukey’s test at 5% (p ≤ 0.05) was used for comparison of means.

3 Results

3.1 Isolation of Fusarium oxysporum

Wilted cotton plants (Fig. 1a) collected from several cotton-growing areas during a survey conducted in 2017, allowed the recovery of high frequency of Fusarium oxysporum.

3.2 Morphological identification and pathogenicity test of Fusarium oxysporum

Fungal colony of Fusarium oxysporum was white cottony and dark-purple undersurface on potato dextrose agar and spores were oval to ellipsoid/ kidney shaped, oval tapering and septate in three cells whereas chlamydospores formed in chain (Fig. 1d). F. oxysporum was found pathogenic and symptoms were developed within 20–25 days after inoculation. Leaves became yellow and browning of vascular tissues was observed (Fig. 1b,c).

3.3 Molecular characterization of Fusarium oxysporum

Molecular characterization of Fusarium oxysporum was done by using the ITS universal primers, ITS4 (TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC) and ITS1 (TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G). The analyses of ITS sequence by BLAST shown that culture was affiliated to specie Fusarium oxysporum with 99% homology. Accession number of ITS sequence assigned to GenBank was MN396369. The result of alignment was in agreement with previously published sequence of the identified species.

3.4 In vitro efficacy of weed extracts against Fusarium oxysporum

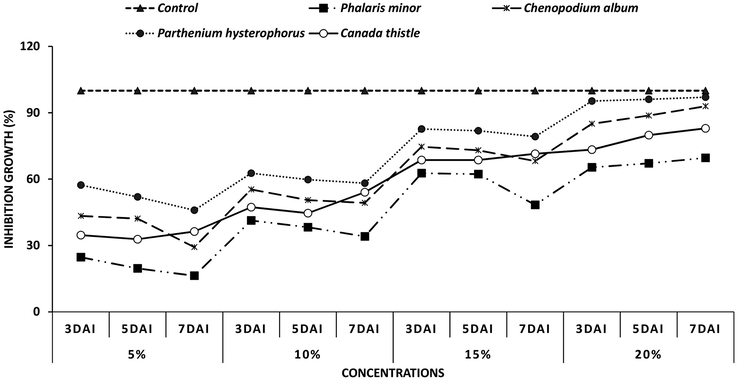

Four weed extracts viz., C. album, P. hysterophorus, C. thistle and P. minor were tested against F. oxysporum. Inhibition percentage of fungal radial growth was calculated using four different concentration viz., 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% and compared with positive control (C+). Significant results were recorded at maximum concentration, 20%, used during experiment and were compared with treatment Tebuconazole, fungicide used as positive control, showing 100% inhibition to fungal pathogen. Data shown that maximum inhibition, 97%, was shown in plates treated with P. hysterophorus at 20% concentration after 7 days of inoculation. Extract of C. album shown 92% inhibition of Fusarium oxysporum at 20% concentration 7DAI. The inhibition percentage in treatment C. thistle was 82% where as 69% inhibition was recorded in treatment P. minor. At lower concentration of 5%, 10% and 15% the significant inhibition of Fusarium oxysporum was recorded after 3 days of inoculation whereas after 5DAI and 7DAI the efficacy of weed extracts started decreasing. Results shown that the antifungal activity of weed extracts was proportional to the concentration applied (Fig. 2).

Inhibition percentage of Fusarium oxysporum in response to weed extracts applied at concentration of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%

3.5 In vitro efficacy of Trichoderma harzianum against Fusarium oxysporum

The data of percentage inhibition of radial growth shown significant, 98%, inhibition of Fusarium oxysporum on PDA.

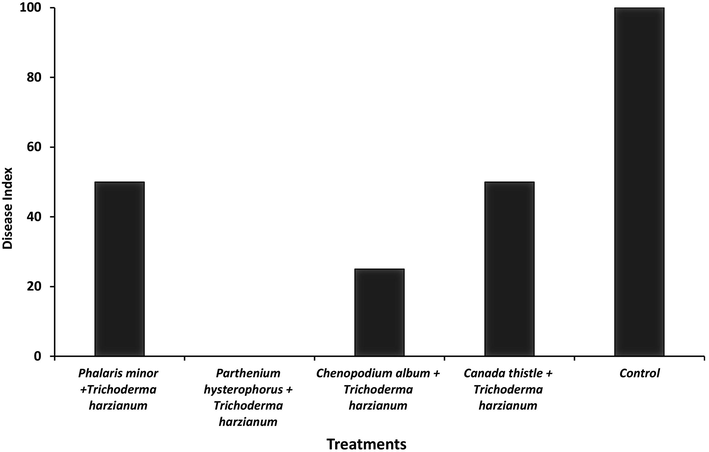

3.6 Efficacy of T. harzianum-amended weed extracts in pot trial

The disease index was calculated after harvesting and observing the cotton roots. Four weed extracts amended with T. harzianum were applied on cotton plants, inoculated with Fusarium oxysporum and compared with un-inoculated control. The untreated control shown 100% disease appearance. The inoculated cotton plants treated with P. hysterophorus + T.H shown no disease as compared to untreated control whereas in treatment C. album + T.H 25% disease index was calculated. However, treatments C. thistle + T.H and P. minor + T.H shown 50% disease index (Fig. 3). The data of disease index shown that consortium of weed extract and T. harzianum is a strong antifungal mixture for the management of Fusarium oxysporum.

Disease index of plants treated with weed extracts amended with Trichoderma harzianum.

4 Discussion

The F. oxysporum is a very destructive fungal pathogen and causes heavy losses in cotton worldwide (Cox et al., 2019). For the proper identification of pathogen, the survey of cotton growing areas was done. The pathogen was identified on morphological (Fig. 1a–d) and molecular basis and identified as Fusarium oxysporum. Among four weed extracts, maximum antifungal response (97%) was shown by P. hysterophorus whereas inhibition percentage of T. harzianum was recorded 98% against F. oxysporum. Combination of P. hysterophorus + T. harzianum was proved effective with no disease as compared to control (100%). Similar survey was conducted by González et al., 2015 in month of August-November for the molecular identification of Fusarium spp causing wilt in cotton.

Several methods including host resistance, cultural, physical, biological and chemical methods are being practiced by the researchers for the management of cotton wilt. Due to less research in developing host resistance, limitations and increasing environmental pollution by use of other methods, various studies are being devoted to apply a biological control as nature-friendly alternative method (Siameto et al., 2010a; 2010b;; Soria et al., 2012). Weeds are responsible for the huge losses to the biodiversity, economy, agriculture, and health of human beings and health of livestock. Beside their detrimental effects, many reports are available on the antifungal, antihelmintic, antiviral, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties of weed plants (Table 1) (Malik and Singh, 2010; Govindarajan et al., 2006). Evaluation of weed extracts to explore their antifungal activity remain an area of interest. However, studies regarding the use of weed extracts amended with T. harzianum against plant pathogens, as antifungal agents, are scanty.

Antimicrobial potential of plant extracts is due to saponins, tannins, flavonoids, essential oils and phenolic compounds (Sales et al., 2016) whereas T. harzianum act directly on plant pathogens by different mechanism via lysis, hyperparasitism, competition and competition (Howell, 2006; Siameto et al., 2010a; 2010b). In present research, the weed extracts used alone and amended with T. harzianum showed significant antifungal activity against F. oxysporum. The similar antifungal response of weed extracts (L. camara and P. hysterophorus) was documented by Deepika and Singh (2011) against fungal pathogen, Alternaria spp. Srivastava and Singh, (2011) also reported that L. camara and P. hysterophorus exhibit antifungal properties against Alternaria spp. Pal et al. (2013) explored the amazing fungicidal properties of P. hysterophorus against fungal pathogens. In our findings, C. album, P. hysterophorus, C. thistle and P. minor showed antifungal response against F. oxysporum. P. hysterophorus showed maximum, 97%, antifungal response against F. oxysporum. Our results are in line with the study conducted by Pal and Kumar (2013) to check the mycelial inhibition percentage of F. oxysporum against weed extracts of P. hysterophorus and Achyranthus aspera. Present findings are also supported by Jalander and Gachande (2012) the extracts of Datura innoxia and Datura stramonium showed antifungal response against F. oxysporum and Alternaria solani at 20% concentration.

In current study, consortium of P. hysterophorus-TH, P. minor-TH, C. album-TH and C. thistle-TH significantly inhibited F. oxysporum. There is no work reported on formulation of weed extracts amended with Trichoderma harzianum and their evaluation against plant pathogens. P. minor also significantly inhibited the pathogen to 69% alone and 50% disease index was recorded in combination with T. harzianum. There is no work reported on P. minor as antifungal agent against F. oxysporum. The present work describing the use of weed extracts + T. harzianum against F. oxysporum is innovative (Deepika and Singh, 2011) and an important step in developing plant based ecofriendly fungicides for the management of F. oxysporum.

5 Conclusion

The F. oxysporum causes heavy losses both in quality and quantity of this crop. Use of synthetic chemical fungicide for the management of this fungal pathogen causing serious environmental hazards. The use of weed extracts (C. album, P. hysterophorus, C. thistle and P. minor) alone and amended with T. harzianum is a new, innovative, effective, ecofriendly and economical approach for the management of F. oxysporum in cotton.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge Higher Education Commission (HEC) for support and funding through SRGP-1866. The authors would also extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2020/218), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Phytochemical constituents of weeds: baseline study in mixed crop zone agro-ecosystem. Pak. J. Weed Sci. Res.. 2013;19:2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation of Trichoderma and Evaluation of their Antagonistic Potential against Alternaria porri. J. Phytopathol.. 2014;162(9):567-574.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial potencies of selected native African herbs against water microbes. J. King Saud Univ. – Sci.. 2020;32(4):2349-2357.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Potential of Fusarium wilt-inducing chlamydospores, in vitro behaviour in root exudates and physiology of tomato in biochar and compost amended soil. Plant Soil. 2016;406(1-2):425-440.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activities (in vitro) of some plant extracts and smoke on four fungal pathogens of different hosts. Pakistan J. Biol. Sci.. 2002;5(3):307-309.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In-vitro antibacterial and antifungal properties of the organic solvent extract of Argemone mexicana L. J. King Saud Univ. – Sci.. 2020;32(3):2053-2058.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dry heat and hot water treatments for disinfesting cottonseed of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum. Plant Dis.. 2010;94(12):1469-1475.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fusarium wilt of cotton: management strategies. Crop Prot.. 2015;73:40-44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Return of old foes — recurrence of bacterial blight and Fusarium wilt of cotton. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol.. 2019;50:95-103.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal potential of two common weeds against plant pathogenic Fungi-Alternaria sps. Asian J. Exp. Biol. Sci.. 2011;2:525-528.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-bacterial activity of extract and the chemical composition of essential oils in Cirsium arvense from Iran. J. Essential Oil Bearing Plants. 2017;20(4):1162-1166.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Floral scent of Canada Thistle and its potential as a generic insect attractant. J. Econ. Entomol.. 2008;101(3):720-727.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular identification of Fusarium species isolated from transgenic insect-resistant cotton plants in Mexicali valley, Baja California. Genet. Mol. Res.. 2015;14(4):11739-11744.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antiulcer and antimicrobial activity of Anogeissus latifolia. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2006;106(1):57-61.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of soil inoculum density of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum race 4 on disease development in cotton. Plant Dis.. 2009;93(12):1324-1328.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the mechanisms employed by Trichoderma virens to effect biological control of cotton diseases. Phytopathology®. 2006;96(2):178-180.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of the flavonoids and some biological activities of two Chenopodium species. Chem. Nat. Compd.. 2007;43(1):24-28.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Detection of flumethrin acaricide residues from honey and beeswax using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) technique. J. King Saud Uni. Sci.. 2020;32(3):2229-2235.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of aqueous leaf extracts of Datura sp. against two plant pathogenic fungi. Int. J. Food Agric. Veter. Sci.. 2012;2:131-134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of California Isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum. Plant Dis.. 2005;89(4):366-372.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial potential of Parthenium hysterophorus Linn. plant extracts. Int. J. Life Sci. Biotechnol. Pharmacol. Res.. 2013;2:458-463.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial effects of essential oils against uropathogens with varying sensitivity to antibiotics. Asian J. Biol. Sci.. 2010;3(2):92-98.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fusarium species: An Illustrated manual for identification. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press; 1983. p. :p193.

- Flavonoid profile of the cotton plant, gossypium hirsutum: a review. Plants. 2017;6(4):43.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening and in vitro antifungal investigation of Parthenium hysterophorus extracts against Alternaria alternate. Int. Res. J. Pharm.. 2013;4:190-193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activity of some common weed extracts against phytopathogenic fungi Alternaria spp. Int. J. Uni. Pharm. life Sci.. 2013;3:6-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Economic perspectives of cotton crop in Pakistan: A time series analysis (1970–2015) (Part 1) J. Saudi Soc. Agricul. Sci.. 2019;18(1):49-54.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toxicology, phytochemistry, bioactive compounds and pharmacology of Parthenium hysterophorus. J. Med. Plants Stud.. 2013;1:126-141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activity of plant extracts with potential to control plant pathogens in pineapple. Asian Pacific J. Trop. Biomed.. 2016;6(1):26-31.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antagonism of Trichoderma farzianum isolates on soil borne plant pathogenic fungi from Embu District, Kenya. J. Yeast Fungal Res.. 2010;1:47-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antagonism of Trichoderma harzianum isolates on soil borne plant pathogenic fungi from Embu District, Kenya. J. Yeast Fungal Res.. 2010;1:47-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endophytic bacteria from Pinus taeda L. as biocontrol agents of Fusarium circinatum Nirenberg & O'Donnell. Chil. J. Agric. Res.. 2012;72:281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal potential of two common weeds against plant pathogenic fungi-sps. Alternaria. 2011:525-528.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of excessive irrigation on the breakdown of root rot diseases in cotton crop from Sakrand Sindh. Sindh Uni Res. J. 2013:45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological and molecular characterization of Fusarium spp. associated with olive trees dieback in Tunisia. 3 Biotech. 2017;7(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nitrate protects cucumber plants against Fusarium oxysporum by regulating citrate exudation. Plant Cell Physiol.. 2016;57(9):2001-2012.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of the antifungal activity of Trichoderma longibrachiatum T6 and assessment of bioactive substances in controlling phytopathgens. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol.. 2018;147:59-66.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]