Translate this page into:

Molecular characterisation of csgA gene among ESBL strains of A. baumannii and targeting with essential oil compounds from Azadirachta indica

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Microbiology, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences [SIMATS], Saveetha University, P.H. Road, Chennai, Tamilnadu 600077, India. smilinejames25@gmail.com (A.S. Smiline Girija)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objectives

A. baumannii is considered as a “red alert” nosocomial human pathogen and exhibits an extensive antibiotic resistance spectrum. The biofilm formation mediated by the csgA is a potent virulence factor in A. baumannii and targeting the same would be of a novel strategy to control A. baumannii infections. The aim of the present study is thus to evaluate the anti-biofilm activity of essential bio-compounds from Azadirachta indica against the ESBL producing strains of A. baumannii by in-vitro and in-silico studies.

Methods

Biofilm formation by Semi-quantitative adherence assay was performed for the 73 strains of ESBL producing A. baumannii. Genomic DNA was extracted and molecular characterization of csgA gene was done by PCR amplification with further sequencing. In-vitro anti biofilm assay from crude extract of A.indica was performed which was then followed by the in-silico docking involving retrieval of csgA protein and ligand optimisation, molinspiration assessment on drug likeliness, docking simulations and visualisations.

Results

Biofilm assay showed 58.9%, 31.5% and 0.09% as high grade, low grade and non-biofilm formers respectively. 20.54% (15/73) of the screened genomes showed positive amplicons for the csgA gene associated with biofilm formation among the ESBL producing strains of A. baumannii. All the ceftazidime, cefipime and cefotaxime resistant strains showed the presence of csgA gene (100%; 15/15), followed by 46.6% (7/15) resistant isolates for ceftriaxone. In-vitro crystal violet viability assay showed MBEC50 and MBEC90 at a concentration of 20 µl and 40 µl respectively. In-silico assessments on the essential oil compounds from neem showed imidazole to exhibit the highest interaction with least docking energy and high number of hydrogen bonds.

Conclusion

The current study emphasises that imidazole from A.indica to be a promising candidate for targeting the csgA mediated biofilm formation in ESBL strains of A. baumannii. However, further in-vivo studies have to be implemented for the experimental validation of the same.

Keywords

A. baumannii

Biofilm

csgA gene

A. indica

1 Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii is a small, rod shaped, non-motile, non-fermentative, gram negative bacterium (Beijerinck, 1911). The bacterium has been designated as a “red alert” human pathogen, because of its extensive antibiotic resistance spectrum. In recent years, They are generating a great alarm among the medical fraternity. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recently identified MDR pathogens within the acronym ESKAPE pathogens (Cerqueira and Peleg, 2011; Rice, 2008). A. baumannii has a high incidence among immuno-compromised individuals, particularly those who have experienced a prolonged (>90 d) hospital stay (Montefour et al., 2008). The cross-transmission of microorganisms from abiotic surfaces has got a significant role in the ICU-acquired infections. Its ability to withstand desiccation and starvation by producing biofilms as a community of bacteria enclosed within a protective polymeric matrix is considered to be an important factor that attributes to the spread of A. baumannii in these environments (Russotto et al., 2015; D’Agata et al., 1999; Boyce, 2007; Jawad et al., 1996, 1998a, 1998b). The biofilm formation is a potent virulence factor in A. baumannii as it increases the survival rate of this bacterium in its persistence in the hospital environment, increasing the probability of causing nosocomial infections and outbreaks. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases is a rapidly evolving group of enzymes capable of degrading the majority of β-lactam antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins and aztreonam. The incidence of infections caused by ESBL producing pathogens is increasing every year, mainly because of inadequate antimicrobial therapy (Będzichowska et al., 2019).

It is exciting to note that in the initiation and progression of biofilm formation by A. baumannii, the bacterium produces an extracellular matrix consisting of curli amyloid fibers and cellulose. Curli fibers bring about adhesion to surfaces, cell aggregation, and biofilm formation. Curli fibers are potent host inflammatory response inducers and also mediate host cell adhesion and invasion (Barnhart and Chapman, 2006). Curli-specific gene (csg) operons encode the major structural components and accessory proteins and contribute to the Curli fiber production. The export of csg proteins to the outer surface is guided by the accessory proteins, csgG, csgE and csgF (Jain et al., 2017). csgA gene, the major subunit of the curli amyloid fiber, is synthesized in the cytoplasm and transported as an unfolded protein to the cell surface, where upon interaction with the csgB nucleator protein, assembles to form extracellular amyloid polymers (Hammar, Bian and Normark, 1996; Hammer, Schmidt and Chapman, 2007) substantiating the role of csgA in the bio-film formation.

Thus targeting csgA would be a novel therapeutic approach to combat the menace of drug resistant strains of A. baumannii. Amidst many natural plants in India, Azadirachta indica is considered as a medicinal plant in abundance and the phytochemical analysis of the same had documented the presence of alkaloids, tannins, glycosides, saponins, flavonoids and terpenoids (Sudevan et al., 2013). In many overviews on the bio-active constituents from A. indica, various compounds were known for their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties (Alzohairy, 2016). With this background the present study is intended to molecularly characterize the presence of csgA gene among the multi-drug resistant strains of A. baumannii, together with the in-vitro and in-silico docking analysis of the bio-active compounds from A. indica against csgA.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Semi-quantitative adherence assay for the detection of biofilm formation

73 ESBL producing strains of A. baumannii reported in our earlier studies (Kouidhi et al., 2010) were cultured separately in a 96-well flat bottomed microtitre plate was used for culturing as reported in earlier studies (Kelleher and Broin, 1991). With 200 µl of the fresh broth culture in typticase soy broth (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) with 0.25% glucose (w/v), the assays were done in triplicate for each strain. Then at 37 °C/24 hrs with negative control (broth + 0.25% glucose) and positive control (known biofilm forming strain of A. baumannii earlier detected), the plates were incubated. To remove the free cells, the incubated wells were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and with 95% ethanol/5min the adhered bacteria were fixed and dried. Finally the wells were stained with 100 µl of 1% w/v crystal violet solution (HiMedia), for 5 mins. Distilled water was added to remove the excess stain and the wells were dried. Biofilm positive and negative strains of A. baumannii were used as the standards for validation of the biofilm production. Optical density was measured in the plate reader at 570 nm (OD570), and the biofilm formation was recorded as high (OD570 ≥ 1), low (0.1 ≤ OD570 < 1) or negative (OD570 < 0.1) (Avila-Novoa et al., 2019).

2.2 Extraction of genomic DNA

73 multi-drug resistant strains of A. baumannii which were maintained in 80%/20% (v/v) glycerol in LB medium at −80 °C from our repertoire used in our earlier studies were retrieved (Smiline, Vijayashree and Paramasivam, 2018). Fresh cultures were prepared on MacConkey agar by incubating at 37 °C/24 h. Qiagen DNA extraction Kit was used in the extraction of genomic DNA which was carried in accordance to the manufacturer’s instruction and was stored at –20 °C until further use.

2.3 PCR amplification of csgA gene and sequencing

The primer sequences ACTCTGACTTGACTATTACC and GATGCAGTCTGGTCAAC (Zeighami et al., 2019) were annealed at 50 °C for 36 cycles in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf Mastercyler, Germany). Briefly, 15 µl of the genomic DNA was resolved with the help of 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide in Tris borate buffer at 90v for about 40 min jointly with a suitable 1.5 Kbp DNA ladder as marker. Big dye terminator cycle sequencing kit, bioedit sequence analyser and 3730XL genetic analyser were used for bidirectional sequencing of csgA amplicon product which in turn is done by alignment of sequences from the forward and reverse primers. Finally BLAST analysis is done for similarity check of nucleotides. The sequences were then aligned by ClustalW software for multiple sequence alignment using default parameters.

2.4 In vitro anti – biofilm assay with A. indica essential oils

2.4.1 Plant source

Plant sources were obtained from the aerial leaves of A. indica and they were subjected to hydro distillation for the extraction of essential oils. Anhydrous sodium sulfate was added to remove the excess water from the extracted oil and was stored in dark vials at 4 °C.

2.4.2 Anti-biofilm assay

A 96 well polystyrene flat bottom plate was used to check the anti-biofilm formation of the crude extracts from A. indica on A. baumannii as described in earlier studies (Sánchez et al., 2016). Briefly, sterile trypticase soy broth was used for the preparation of fresh broth suspension of csgA positive of A. baumannii and the suspension was adjusted to 0.5 Mc Farland standards. For comparative purposes, control wells with only medium, organism and oil suspensions (5 µl to 40 µl) were prepared. Incubation of the plates was done at 37 °C for 24 hrs. Then, the supernatant was removed and to remove the free floating cells, each well was washed with sterile distilled water and was air dried for 30 min. 1% of aqueous solution of crystal violet was used for staining and was allowed to stand for 15 min. Then the stain was removed thrice by washing with distilled water. 250 µl of ethanol was used for solubilizing the wells and a plate reader was used at 570 nm to measure the absorbance. The equation 1 – (test OD570/Control OD570)/100 was used for calculating the inhibition percentage (Gowrishankar et al., 2016). The minimum biofilm inhibition concentration is that which showed 50% and 90% inhibition of biofilm formation.

2.5 Retrieval of csgA and protein optimisation

The crystal structure of csgA protein was obtained from the RCSB protein data bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb). The optimisation of crystal structure of csgA is done by the addition of hydrogen atoms. Kollman united atoms force field was used to assign electronic charges to the protein atoms which was done in Auto Dock tool – 1.5.6 and the RASMOL tool was used for the visualisation of three dimensional structure of csgA protein.

2.6 Ligand preparation and optimisation

The structures of the bio-active derivatives of A. indica was obtained from the chemsketch software. The generated 3D structures were then optimised. The selected ligands were subjected to subsequent conversions by open label molecular converter program. They were then saved in PDB format. The selected ligands were further saved in .mol file.

2.7 Molinspiration assessment of the molecular properties of the selected compounds

The counts of hydrogen bond acceptors and donors in relation to the membrane permeability and bio-availability of the compounds, logP for partition co-efficient, molecular weight of compounds of the basic molecular descriptors were assessed with the help of molinspiration assessment program. The characters of absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of the selected bio compounds were further evaluated on the basis of “The Lipinski’s rule of five” (Benet et al., 2016).

2.8 Docking simulations

Auto Dock tool was used for docking analysis to interpret the affinity between bio-compounds of A. indica against csgA protein of A. baumannii.

2.9 Docking visualisation

Using Discovery studio visualiser, the hydrogen bond interaction between the bio-compounds of A. indica against csgA of A. baumannii were visualised. With further docking score assessments, binding affinities, molecular dynamics and energy simulations, the relative stabilities were evaluated.

2.10 Statistical analysis

The SPSS version 21.0 (Chicago, IL) was used for assessing the statistical significance of the results obtained. At a p-value < 0.05, the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact 2 - tailed tests were applied. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to co-relate the frequency of csgA among the ESBL strains of A. baumannii.

3 Results

3.1 Molecular characterization of csgA gene and its correlation with ESBL’s

Semi-quantitative adherent bioassay for biofilm formation showed 58.9% (43/73), 31.5% (23/73) and 0.09% (7/73) as high grade, low grade and non-biofilm formers. All the 43 strains of high grade biofilm formers showed resistance against ceftazidime, cefipime and cefotaxime and 76.7% (33/43) showed resistance against ceftriaxone. All the low grade biofilm formers showed resistance against ceftazidime, cefipime and cefotaxime. 20.54% (15/73) of the screened genomes showed positive amplicons for the csgA gene associated with biofilm formation among the ESBL producing strains of A. baumannii (Supplementary Fig. 1). The selection of the ESBL strains were done based on the earlier studies (Smiline et al., 2018; Rawat and Nair, 2010). A positive value was obtained on Pearson correlation analysis which suggest the co-relation of occurrence of csgA gene with ESBL strains (p-value < 0.05). The presence of csgA gene was found to be (100%; 15/15) in all the ceftazidime, cefipime and cefotaxime resistant strains, followed by 46.6% (7/15) resistant isolates for ceftriaxone.

3.2 Anti-biofilm assay results

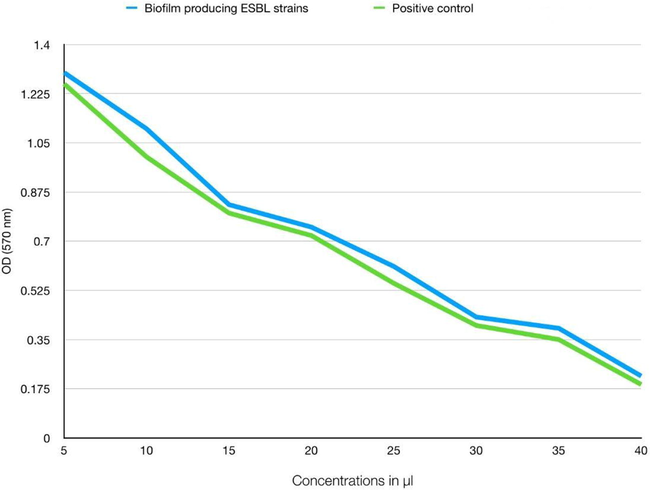

Crude extract of A. indica showed minimal biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC50) at 20 µl concentration on crystal violet assay indicating 50% inhibition of biofilm formation by A. baumannii (p < 0.05). Similarly, they showed MBEC90 at 40 µl concentration indicating 90% inhibition of biofilm formation (Fig. 1).

Anti-biofilm assay showing MBEC90 at 40 µl concentration indicating 90% inhibition of biofilm formation using strain control, medium control, oil suspension control.

3.3 Structural retrieval of the csgA protein from A. baumannii

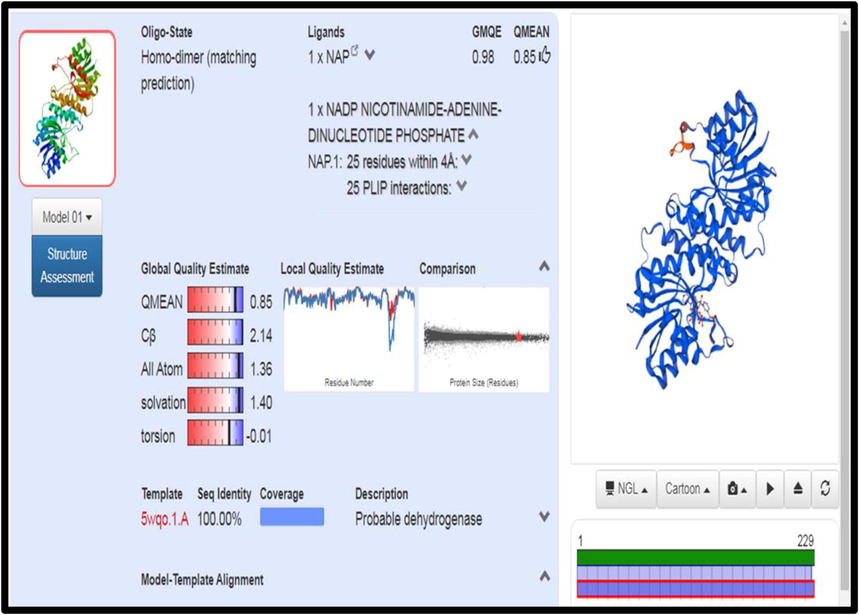

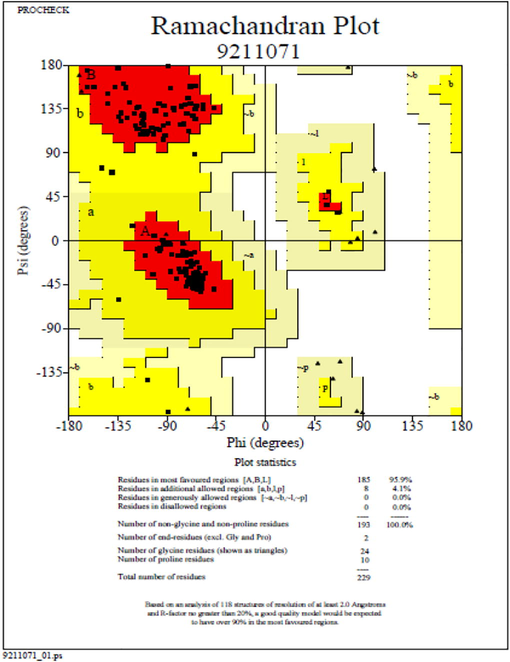

FASTA sequence of csgA from A. baumannii was retrieved from UNIPROT database and its sequence ID was A0A335NTF8. Using the Swissmodel server, homology model was made with 5WQO – A chain as template (Fig. 2). The model was highly plausible with 100% sequence identity with the template. Besides, the Ramachandran plot showed 95.9% of residues in most favoured regions and with no residues in disallowed region (Fig. 3). The 3D structure of csgA was visualized using RASMOL with the pink colour denoting the alpha-helix, yellow arrow denoting the beta sheets and white colour denoting the turns.

Prediction of csgA structure and homology modelling in Swissmodel Server.

Validation of the predicted structure using Ramachandran plot.

3.4 Structural retrieval of the ligands from A. indica essential oil compounds

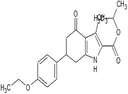

ACD Chemsketch was used for achieving the ligand optimization and Open Babel molecular converter tool was used in retrieving the compatible format. The 2D and 3D structures of the ligands from A. indica retrieved, and its SMILES format, are shown in Table 1.

Compound name

2D

3D

SMILES

Mol formula

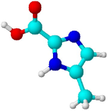

Imidazole-2-carboxylic acid

CC1 = CN = C(N1)C(=O)O

C5HN2O2

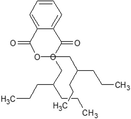

bis (2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester

CCCC(CCC)COC(=O)C1 = CC = CC = C1C(=O)OCC(CCC)CCC

C24H38O4

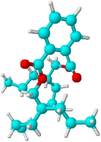

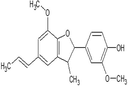

Dehydrodiisoeugenol

CC = CC1 = CC2 = C(C(=C1)OC)OC(C2C)C3 = CC(=C(C = C3)O)OC

C20H22O4

4-Dehydroxy tyramine

C1OC2 = C(O1)C = C(C(=C2)C = NCCC3 = CC = CC = C3)[N + ](=O)[O-]

C16H14N2O4

Trihydroindole

CCOC1 = CC = C(C = C1)C2CC3 = C(C(=C(N3)C(=O)OC(C)C)C)C(=O)C2

C21H25NO4

3-Quinolinecarboxylic acid

CCOC(=O)C1 = CNC2 = C(C1 = O)C = C(C = C2F)F

C12H9F2NO3

Ceftazidime

CC(C)(C(=O)O)ON = C(C1 = CSC(=N1)N)C(=O)NC2C3N(C2 = O)C(=C(CS3)C[N + ]4 = CC = CC = C4)C(=O)[O-]

C22H22N6O7S2

3.5 Molinspiration assessment towards drug likeliness

Based on the calculation of the ion channel modulation, GPCR ligand, nuclear receptor ligand, kinase inhibitor, enzyme inhibition and protease inhibition, the bioactivity score prediction of essential compounds of A. indica against csgA of A. baumannii towards drug likeliness was assessed and tabulated (Table 2).

Compounds

M.wt

Hydrogen Bond Donor

Hydrogen Bond Acceptor

miLogP

Rotatable bonds

nViolations

TPSA (Ǻ)

Volume

N atoms

Imidazole-2-carboxylic acid

126.11

2

4

−0.17

1

0

65.98

104.44

9

bis (2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester

390.56

0

4

8.04

16

1

52.61

407.90

28

Dehydrodiisoeugenol

326.39

1

4

4.10

4

0

47.93

306.90

24

4-Dehydroxy tyramine

298.30

0

6

3.35

5

0

76.66

259.58

22

Trihydroindole

355.43

1

5

4.54

6

0

68.40

335.84

26

3-Quinolinecarboxylic acid

253.20

1

4

0.10

3

0

59.17

203.20

18

Ceftazidime

546.59

4

13

–5.68

9

2

191.23

439.78

37

3.6 Docking analysis of the A. indica derivatives against csgA of A. baumannii

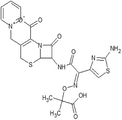

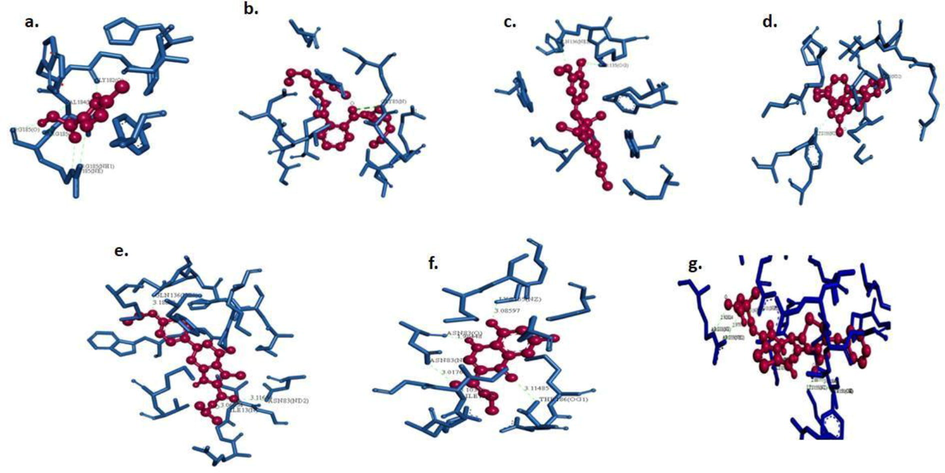

LGA was used for selecting the best conformers. The bond interactions between the essential compounds from A. indica and csgA of A. baumannii in the stick model by discovery studio visualisations between the selected compounds are shown in Fig. 4. The csgA protein interactions with bio-active compounds from A. indica are shown in Table 3. The docking scores, number of hydrogen bonds formed, torsional energy between the ligands and the drugs were recorded (Table 4). The overall docking energies and interactions between the csgA and the A. indica biocompounds were assessed based on the ligand efficiency, intermolecular energy, electrostatic energy, vdW + Hbond + desolv energy, internal energy and torsional energy in kcal/mol (Table 5). The data also showed the least binding energy, van der Waals, π-σ interactions, alkyl/π-alkyl interactions, π-sulphur interactions and imidazole compound was assessed as the promising interacting compound from A. indica.

Visualizing hydrogen interactions between csgA with a. imidazole-2-carboxylic acid b. bis (2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester c. dehydrodiisoeugenol d. 4-dehydroxy tyramine e. trihydroindole f. 3-quinolinecarboxylic acid g. ceftazidime.

Compound name

CsgA

Ligand atoms

Distance (Ǻ)

Docking Energy (Kcal/Mol)

Residue

Atom

Imidazole-2-carboxylic acid

ARG185

NH1

N

2.98

–5.66

ARG185

NE

O

2.76

ARG185

N

O

2.86

ARG185

N

O

2.96

ARG185

O

H

2.26

GLY182

O

H

1.90

VAL184

N

O

3.17

bis(2-propylpentyl) phthalate

GLY85

N

O

3.15

–4.07

Dehydrodiisoeugenol

SER135

OG

NE2

3.02

–8.03

SER135

OG

H

2.13

GLN136

NE2

H

2.87

4-Dehydroxy tyramine

ASN83

ND2

O

2.87

–8.9

LYS155

NZ

O

2.70

LYS155

NZ

O

3.16

Trihydroindole

GLN136

NE2

O

3.18

–9.39

ASN83

ND2

O

3.11

ILE13

N

O

3.06

3-Quinolinecarboxylic acid

THR186

OG1

O

3.11

–6.94

ASN83

ND2

O

3.01

ILE13

N

O

3.10

LYS155

NZ

F

3.08

ASN83

O

H

1.98

Ceftazidime

ARG33

NH2

O

2.97

–9.94

ARG33

NE

O

2.92

ARG11

NH2

O

3.06

TYR151

OH

O

3.07

LYS155

NZ

O

2.88

GLY85

O

H

2.03

GLY85

N

O

2.78

CsgA docking with compounds

Number of hydrogen bonds

Binding energy

Inhibition constant

Ligand efficiency

Intermolecular energy

vdW + Hbond + desolv Energy

Electrostatic energy

Torsional energy

Total internal Unbound

Imidazole-2-carboxylic acid

7

–5.66

70.45

–0.63

–6.26

–5.37

–0.89

0.6

–0.43

bis (2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester

1

–4.07

1.03

–0.15

–8.85

–8.8

–0.04

4.77

–2.64

Dehydrodiisoeugenol

3

–8.03

1.3

–0.33

–9.52

–9.37

–0.15

1.49

–0.31

4-Dehydroxy tyramine

3

–8.9

297.89

–0.4

–10.39

–9.13

–1.26

1.49

–0.99

Trihydroindole

3

–9.39

131.66

–0.36

–11.18

–11.02

–0.16

1.79

–1.13

3-Quinolinecarboxylic acid

5

–6.94

8.12

–0.39

–7.84

–7.58

–0.26

0.89

–0.08

Ceftazidime

7

–9.94

51.46

–0.27

–13.22

–10.81

–2.41

3.28

–2.35

CsgA docking with compounds

Hydrogen bonds interactions

van der Waals interactions

π-σ interactions/ amide-π stacked interactions/ π-cation interactions

alkyl/π-alkyl interactions

π-sulfur interaction

Imidazole-2-carboxylic acid

7

4

1

1

–

bis (2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester

1

7

–

4

–

Dehydrodiisoeugenol

3

3

2

5

–

4-Dehydroxy tyramine

3

6

–

3

–

Trihydroindole

3

9

1

8

–

3-Quinolinecarboxylic acid

5

3

1

6

1

Ceftazidime

7

14

1

5

–

4 Discussion

The potent virulence factor of A. baumannii is its ability to form biofilms in a four major step process viz., attachment of bacteria to the surface, formation of micro-colony, maturation of biofilms and finally its detachment leading to further colonisation. In A. baumannii, formation of biofilm is mediated by cell to cell adhesion through curli fibers, ascribing the virulence and pathogenicity. Thus the present study is intended to molecularly characterise the csgA gene and the association of its frequency with the ESBL producing strains of A. baumannii. Curbing the development of biofilms would be an alternate alternative strategy to battle against the drug resistant strains of A. baumannii. Our study had thus assessed the anti-biofilm activity of the A. indica extract against csgA positive strains of ESBL producing A. baumannii.

Earlier studies demonstrate the occurrence of genotypic detection of putative virulent factors like csgA from A. baumannii to be 63.63% (Tavakol et al., 2018). Another study had reported the occurrence of csgA gene to be about 70% (Darvishi, 2016). A study by Daryanavard et al., had reported the occurrence of the same to be about 55% (Daryanavard and Safaei, 2015). Another study in Iran reported the incidence of csgA gene to be 12.39% which is lower than our studies (Momtaz et al., 2015). In view with this, our study shows about 20.54% occurrence of the csgA gene substantiating the correlation of the same with the ESBL producing strains of A. baumannii. In contradiction a study shows no occurrence of csgA among multi drug resistant strains which highlights the role of some other genes ascribing the same (Zeighami et al., 2019). So, it is obvious that the csgA gene associated biofilm production may vary in its expression and thus requires periodical monitoring to further probe into the insights of its potent virulence role.

We also assessed the anti-biofilm effect of A. indica bio-compounds in the present study as many earlier reports had detailed the characterization of phenolic compounds up to its structural elucidations (Mistry et al., 2014). Anti-biofilm assay was proceeded with the crude extracts rather than the purified compounds for the in-vitro analysis. The oil treated and the oil untreated groups on comparison showed anti-biofilm effect significantly (p < 0.05). For the in-vitro assessments of the anti-biofilm activity, we employed the gold standard crystal violet staining method as it is highly cost effective, adaptable and less time consuming method (Singaravelu et al., 2019). Earlier studies had no documentation on the anti-biofilm activity of A. indica against the ESBL strains of A. baumannii, this study intends to give an insight of biofilm inhibition on the same in csgA producing ESBL-A. baumannii.

Selection of the bioactive compounds from A. indica was based on the detailed analysis from earlier literatures (Chaichoowong et al., 2017). The essential oil compounds from A. indica had been selected for in-silico assessments, as they encompass potent hydrophobic biomolecules and are highly suitable for nano-formulations based on earlier reports (da Costa et al., 2014). We did not perform the purification protocols and thus the study limits itself with the anti-biofilm activity done only with the crude extracts. With the aid of the computational bio-informatics tools and databases, the best fit of the compounds to target the csgA was achieved efficiently. Based on the strength score and pose, a promising ligand – receptor complex was obtained. From the molinspiration results, the drug likeliness was promising with no violations for all the selected bio-compounds except bis (2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester.

Comparing the molecular weight of all the compounds, imidazole-2-carboxylic acid possessed the least molecular weight of 126.11 and bis (2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester possesses the higher molecular weight of 390.36. Other compounds showed a molecular weight ranging between 200 and 370. Assessments on the hydrogen bonds donor and acceptor property, bis (2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester had the greatest number of rotatable bonds of about 16 together with the greatest miLogP value of −0.17. The TPSA value (Topological Polar Surface Area) of a compound is an important evaluation, as it attributes to the oral bio-availabilty of drugs which should be <140 Å. It is promising to note that all the 6 bioactive compounds that we have selected showed TPSA values of <140 Å.

Evaluation of the overall docking energies showed that imidazole-2-carboxylic acid got the greatest number of hydrogen bonds while bis(2-propylpentyl) phthalate has got the least. Trihydroindole shows the least binding energy of –9.39 whereas bis(2-propylpentyl) phthalate show about –4.07. Dehydrodiisoeugenol possessed a greatest inhibition constant whereas imidazole-2-carboxylic acid showed the least inhibition constant. Ligand efficiency, electrostatic and torsional energy were found to be greater in bis(2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester.

We can also infer from the overall interaction that imidazole-2-carboxylic acid showed 7 hydrogen bond interactions, 4 vanderwaal’s interactions, 1 π –σ interaction and 1 π – alkyl interaction which states the stabilisation of the binding structures. This was followed by 3-Quinolinecarboxylic acid with 5 hydrogen bond and bis(2-propylpentyl) phthalate ester showing single hydrogen bond interaction. Trihydroindole has got the highest Vanderwaal interaction followed by bis(2-propylpentyl) phthalate. Dehydrodiisoeugenol showed 2π –σ interactions which is the highest. π–alkyl interactions were found to be greater in trihydroindole. On the other hand, only 3-Quinolinecarboxylic acid showed π –sulfur interactions.

5 Conclusion

The present investigation had documented the presence of csgA gene among the ESBL positive A. baumannii strains which may be considered as a serious threat in hospital environment. In-vitro anti-biofilm activity was promising with the crude extracts of A. indica with imidazole-2-carboxylic acid exhibiting a greater interaction with csgA using computational analysis. However the study requires further experimental analysis for the design of novel drugs from A. indica to combat the menace of biofilm formation in drug resistant strains such as ESBL producers of A. baumannii.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Therapeutics role of Azadirachta indica (Neem) and their active constituents in diseases prevention and treatment. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med.. 2016;2016:1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Novoa, M.-G. et al. (2019) ‘Biofilm Formation and Detection of Fluoroquinolone- and Carbapenem-Resistant Genes in Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii’, The Canadian journal of infectious diseases & medical microbiology = Journal canadien des maladies infectieuses et de la microbiologie medicale / AMMI Canada, 2019, p. 3454907.

- Frequency of infections caused by ESBL-producing bacteria in pediatric ward – single center five-year observation. AOMS. 2019;15(3):688-693.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pigmenten als oxydatieproducten gevormd door bacterien. Versl Koninklijke Akad Wetensch Amsterdam. 1911;19:1092-1103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Environmental contamination makes an important contribution to hospital infection. J. Hosp. Infect.. 2007;65:50-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenicity. IUBMB Life. 2011;63(12):1055-1060.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical profiling of acalypha indica obtained from supercritical carbon dioxide extraction and soxhlet extraction methods. Orient. J. Chem. 2017;33(1):66-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of different formulations of neem oil-based products on control Zabrotes subfasciatus (Boheman, 1833) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) on beans. J. Stored Prod. Res.. 2014;56:49-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- D’Agata, E. M. et al. (1999) ‘Molecular epidemiology of ceftazidime-resistant gram-negative bacilli on inanimate surfaces and their role in cross-transmission during nonoutbreak periods’, Journal of clinical microbiology, 37(9), pp. 3065–3067.

- Darvishi, M. (2016) ‘Virulence Factors Profile and Antimicrobial Resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii Strains Isolated from Various Infections Recovered from Immunosuppressive Patients’, Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal, pp. 1057–1062. doi: 10.13005/bpj/1048.

- Virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance properties of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from pediatrics suffered from UTIs. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci.. 2015;2(11):272-279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cyclic dipeptide cyclo(l-leucyl-l-prolyl) from marine Bacillus amyloliquefaciens mitigates biofilm formation and virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. Pathogens Disease. 2016;74(4):ftw017.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nucleator-dependent intercellular assembly of adhesive curli organelles in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 1996;93(13):6562-6566.

- [Google Scholar]

- The curli nucleator protein, CsgB, contains an amyloidogenic domain that directs CsgA polymerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2007;104(30):12494-12499.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of curli assembly and Escherichia coli biofilm formation by the human systemic amyloid precursor transthyretin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(46):12184-12189.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jawad, A. et al. (1996) ‘Influence of relative humidity and suspending menstrua on survival of Acinetobacter spp. on dry surfaces’, Journal of clinical microbiology, 34(12), pp. 2881–2887.

- Exceptional desiccation tolerance of Acinetobacter radioresistens. J. Hosp. Infect.. 1998;39(3):235-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jawad, A., Seifert, H., et al. (1998) ‘Survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces: comparison of outbreak and sporadic isolates’, Journal of clinical microbiology, 36(7), pp. 1938–1941.

- Microbiological assay for vitamin B12 performed in 96-well microtitre plates. J. Clin. Pathol.. 1991;44(7):592-595.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cell surface hydrophobicity, biofilm formation, adhesives properties and molecular detection of adhesins genes in Staphylococcus aureus associated to dental caries. Microb. Pathog.. 2010;49(1-2):14-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- The antimicrobial activity of Azadirachta indica, Mimusops elengi, Tinospora cardifolia, Ocimum sanctum and 2% chlorhexidine gluconate on common endodontic pathogens: an in vitro study. Eur. J. Dent.. 2014;08(02):172-177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determining the prevalence and detection of the most prevalent virulence genes in Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from hospital infections. Int. J. Med. Lab.. 2015;2(2):87-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Montefour, K. et al. (2008) ‘Acinetobacter baumannii: an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen in critical care’, Critical care nurse, 28(1), pp. 15–25; quiz 26.

- Extended-spectrum ß-lactamases in gram negative bacteria. J. Global Infect. Dis.. 2010;2(3):263.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: No ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis.. 2008;197(8):1079-1081.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial contamination of inanimate surfaces and equipment in the intensive care unit. J. Intensive Care Med.. 2015;3:54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of methanolic plant extracts against nosocomial microorganisms. Evid.-based Complement. Altern. Med.: eCAM. 2016;2016:1572697.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Azadirachta indica crude bark extracts concentrations against gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial pathogens. J. Pharm. Bioall. Sci.. 2019;11(1):33.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular characterization of plasmid-encoded blaTEM, blaSHV and blaCTX-M among extended spectrum β -lactamases [ESBLs] producing Acinetobacter baumannii. Br. J. Biomed. Sci.. 2018;75(4):200-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical extraction and antimicrobial properties of azadirachta indica (neem) Glob. J. Pharmacol.. 2013;7:316-320.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genotyping and distribution of putative virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes of Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from raw meat. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2018;7:120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Virulence characteristics of multidrug resistant biofilm forming Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from intensive care unit patients. BMC Infect. Dis.. 2019;19(1):629.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2020.09.025.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: