Translate this page into:

Mitochondrial COI based molecular identification of harvester termite, Anacanthotermes ochraceus (Burmeister, 1839) in Riyadh Region, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

⁎Corresponding author.

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objective

Termites are well known for being the most destructive pests of household commodities as well as agricultural crops around the globe. The termite fauna (Isoptera) has about 2650 described species worldwide. Several species are the pests of crops and cause damage to wood structures.

Methods

In the present study, 29 specimens of termites collected from different localities of the Riyadh region were identified using mitochondrial gene cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence. COI gene was PCR amplified using universal primers (LCO 1490 and HCO 2198). MEGA7 software was used for phylogenetic tree construction which showed that all 29 specimens grouped together in a single clade indicated close relatedness of all specimens.

Results

All the obtained sequences were submitted into Genbank database and accession numbers were obtained. Phylogenetic analysis showed that all specimens of present research grouped together into a single monophyletic clade, were confirmed to be highly closely related to one another, and proved to be members of the same species. Pairwise nucleotide sequence divergence analysis showed that there was less divergence among all specimens ranging from 0% to 7.8%. Sequence analysis revealed the confirmed precise identification of 29 samples of Anacanthotermes ochraceus with COI barcode analysis.

Conclusions

Molecular data analysis has confirmed morphological identification of all 29 studied samples of A. ochraceus. However, this technology offers strong support for identification of cryptic species which are difficult to identify on the basis of morphological features. Further studies of complete mitogenome can be helpful for accurate identification of termites at species level.

Keywords

Isoptera

Blattodea

DNA barcoding

Anacanthotermes ochraceus

Riyadh

- COI

-

cytochrome c oxidase subunit I

- DNA

-

deoxyribonucleic acid

- CTAB

-

cetyltrimethylammonium bromide

- RAPD

-

Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA

- GPS

-

Global Positioning System

- BLAST

-

basic local alignment search tool

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Termites are members of the insect order Isoptera and are distinguished by their social behavioural traits. A termite colony typically includes a reproductive caste (a queen and a king) as well as workers and soldiers. Out of the 2650 identified termite species worldwide, around 300 species are serious pests that inflict significant damage to houses and timber structures (Edwards and Mill, 1986; Abe et al., 2000). Although various termite species assist in ecological processes, the cycling of nutrients, they are largely known for their economic importance and as a significant pest of agricultural crops (Ahmed et al., 2006). Most of termite research in the Arabian Peninsula, particularly in Saudi Arabia has reported by (Badawi et al., 1986).

DNA barcoding was proposed more than a decade ago as a quick, inexpensive, and simple method of identifying species based on the use of a short and unique gene region to generate the target specimens sequences (Hebert et al., 2003). Many taxonomists are impressed by DNA barcoding, which attempts to link a variety of biological samples with a specific portion of their DNA sequence, primarily the mitochondrial gene “ cytochrome c oxidase subunit I,“ also known as the COI gene (Ebach, 2011). Fragment size of COI has been shown to provide high resolution to identify cryptic species, thereby increasing taxonomy-based biodiversity estimates (Hebert et al., 2004) and its usefulness has been confirmed for several insect orders including Coleoptera (Löbl and Leschen, 2005), Diptera (Scheffer et al., 2006), Ephemeroptera (Ball et al., 2005), Hemiptera (Lee et al., 2011), Hymenoptera (Smith et al., 2008) and Lepidoptera (Hajibabaei et al., 2006).

Other molecular marker like, Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) has also been used to study genetic diversity like for order Neuroptera (Yari et al., 2014). DNA barcodes could aid in the routine identification of insects in applied settings by enabling the recognition of morphologically cryptic species, by associating immature forms with adults (pest management), and by identifying eggs (phytosanitary applications) and fragmentary remains (food quality, ecological analyses) (Park et al., 2011). A crucial evidence of DNA barcoding in animals is that genetic variation within species is lower than genetic variation among species (Hebert et al., 2003; Hebert et al., 2003; Yari et al., 2014). In other words, there is an existence of ‘barcoding gap’ which allow unknown specimens to be identified as an existing species or flagged as a putative undescribed taxon. The presence of global barcoding gap in birds, fish, butterflies (Hebert et al., 2003; Ward et al., 2005; Dincă et al., 2011) sometimes disregarding the importance of local barcoding gaps (Meier et al., 2008). DNA barcoding has proved to be particularly expedient in the study of taxonomically thought-provoking taxa, where morphology-based identifications are maddened due to cryptic diversity (Witt et al., 2006) or phenotypic plasticity (Adamowicz et al., 2004).

In fact, the Saudi termite fauna remains undiscovered, and there is no recent data in the literature. Identification of the pest is important for any successful integrated pest management program. The accuracy of species delimitation is critical to the identify and exploration of insect species. As a result, in present study cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) based DNA barcode of A. ochraceus species of termites from different locations of Riyadh region have been analysed and significance of DNA barcode for accurate identification insect species has been discussed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection and genomic DNA extraction

The Anacanthotermes ochraceus specimens were sampled from agricultural farms covering different habitats of the Riyadh region in 2020. The specimens were collected using an aspirator and hand picking from a broad range of diverse habitats and immediately preserved in absolute ethanol and placed in an ice box and shifted into a fridge at 4 °C in the laboratory. The geographic data of the surveyed sites (e.g. GPS coordinates) is given in the Table 1. For genomic DNA isolation of insect samples, the modified protocol of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method was used (Khan et al., 2017). Liquid nitrogen was used to crystallize the insects and followed by a process of grinding to a fine powder with pestle mortar. CTAB buffer containing 2% β-marceptoethanol (700 µl) was used to make membrane porous and then incubated at 65 °C for cellular disruption. Solution of chloroform and isoamyl alcohol (24:1) were used for separation of DNA and the reaction was precipitated by using 0.6 vol of isopropanol and centrifuge (x 24000 rpm) to pellet down DNA. The pelleted DNA was washed with 70% ethanol to remove the salts and the pellet was air dried. The purification DNA was analysed quantitatively by using nanodrop.

Sample No

Accession Number

Sample Code

Locality/Area

Coordinates

1

ON682943

Shaqra 37 isolate

Shaqraa

25°13.278′N, 45°16.760′E

2

ON529891

HBT 38 isolate

Hawtet bani Tamim (HBT)

23°36.809′N, 46°33.434′E

3

ON682942

Afif 35 isolate

Afif

23°51.837′N, 42°53.568′E

4

ON682941

Afif 34 isolate

Afif

23°51.859′N, 42°53.579′E

5

ON682940

Al-Bajadiah 32 isolate

Al-Bajadiah

24°17.782′N, 43°43.614′E

6

ON682939

Al-Bijadyah 31 isolate

Al-Bajadiah

24°17.804′N, 43°43.625′E

7

ON529890

AlBijadyah 30 isolate

Al-Bajadiah

24°17.783′N, 43°43.584′E

8

ON682937

Al-Bijadyah 26 isolate

Al-Bajadiah

24°18.334′N, 43°44.294′E

9

ON682936

Al-Bijadyah 25 isolate

Al-Bajadiah

24°18.335′N, 43°44.296′E

10

ON529889

AlBijadyah 23 isolate

Al-Bajadiah

24°17.937′N, 43°44.232′E

11

ON529887

Sajir 21 isolate

Sajir

24°09.878′N, 44°36.022′E

12

ON529886

Sajir 19 isolate

Sajir

25°13.332′N, 44°35.856′E

13

ON529885

Sajir 18 isolate

Sajir

25°13.306′N, 44°35.827′E

14

ON529884

Sajir 17 isolate

Sajir

25°12.645′N, 44°36.095′E

15

ON529883

AdDawadmi 16 isolate

Al Dawadmi

24°28.887′N, 44°21.555′E

16

ON529882

AdDawadmi 14 isolate

Al Dawadmi

24°28.701′N, 44°21.178′E

17

ON529881

AdDawadmi 13 isolate

Al Dawadmi

24°28.806′N, 44°20.881′E

18

ON529880

AdDawadmi 12 isolate

Al Dawadmi

24°28.805′N, 44°20.881′E

19

ON529879

AdDawadmi 10 isolate

Al Dawadmi

24°28.887′N, 44°21.540′E

20

ON529877

Dhurma 8 isolate

Dhurma

24°40.894′N, 46°00.364′E

21

ON529876

Dhurma 7 isolate

Dhurma

24°40.896′N, 46°00.367′E

22

ON529870

Dirab1 isolate

Dirab

24°25.094′N, 46°39.093′E

23

ON529892

AsSulayyil 43 isolate

As Sulayyil

20°27.903′N, 45°33.324′E

24

ON682946

As-Sulayyil 44 isolate

As Sulayyil

20°26.063′N, 45°31.302′E

25

ON682945

Al-Aflaj 40 isolate

Al Aflag

21°59.719′N, 46°32.657′E

26

ON682944

Howtat-Bani-Tamim 39 isolate

Hawtet bani Tamim (HBT)

23°36.752′N, 46°39.265′E

27

ON529872

Muzahmiyah 3 isolate

Al Muzahmiyah

24°29.502′N, 46°22.157′E

28

ON529871

Dirab 2 isolate

Dirab

24°25.322′N, 46°39.183′E

29

ON682935

Al-Bijadyah 24 isolate

Al-Bajadiah

24°17.787′N, 43°43.596′E

2.2 Amplification of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I

The isolated genomic DNA of the termite specimens was used as template in PCR reaction for amplification of COI gene. The COI gene was amplified using universal primers (forward primer; LCO 1490: 5′- GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ and reverse primer; HCO 2198: 5′- TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′) (Vrijenhoek, 1994). For reaction, PCR protocol followed by initial denaturation temperature 95 °C for 5 min, denaturation temperature 95 °C for 1-minute, annealing temperature 45 °C for 1 min and elongation/extension temperature 72 °C for 1 min. COI gene amplification was confirmed through Gel electrophoresis using 1% agarose gel.

2.3 Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

Amplified PCR product of desired band size (680–700 bp) was purified using Illustra GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (Healthcare Life Sciences, USA). Purified PCR products were sent to Macrogen Inc. Seoul, South Korea for DNA sequencing. The sequencing data was analyzed using the Lasergene package (DNASTAR, Madison, Wisconsin). Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was used to search out closely related sequences from databases. Closely related sequences were obtained from databases in FASTA format; MEGA7.0 software also was utilised for multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis, while Tree View Software was used for tree display and manipulation. MegAlign application was benefited to pairwise distance analysis for evolutionary divergence between sequences (Tamura et al., 2004).

3 Results

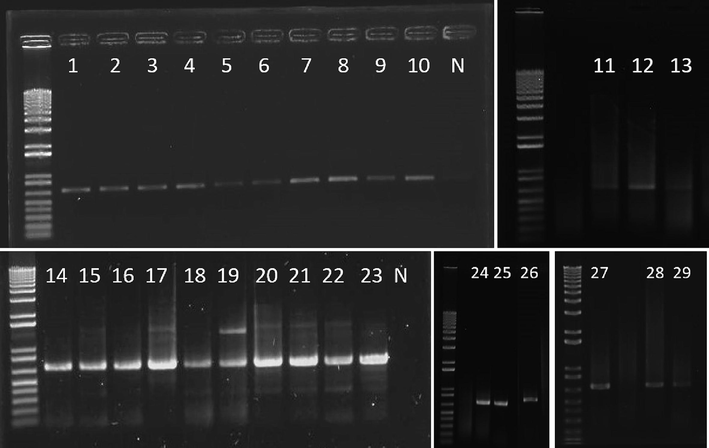

After the DNA extraction and PCR amplification all the amplified PCR products were analysed in 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and showed bright bands of approximately 700 bp size (Fig. 1). The agarose gel shows the samples purity and intensity. The sequenced samples accession numbers are presented in the Table 1.

PCR amplification of COI gene from sampled specimens of Anacanthotermes ochraceus resolved on 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

3.1 Phylogenetic analysis of Anacanthotermes ochraceus

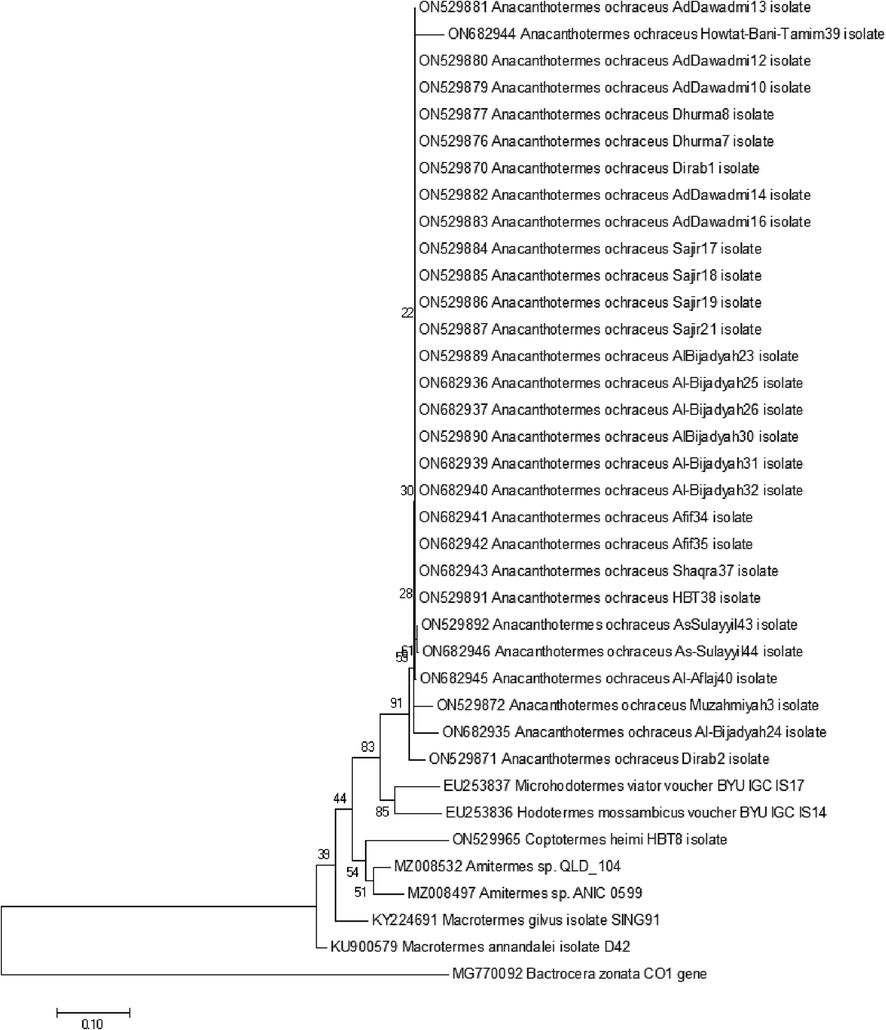

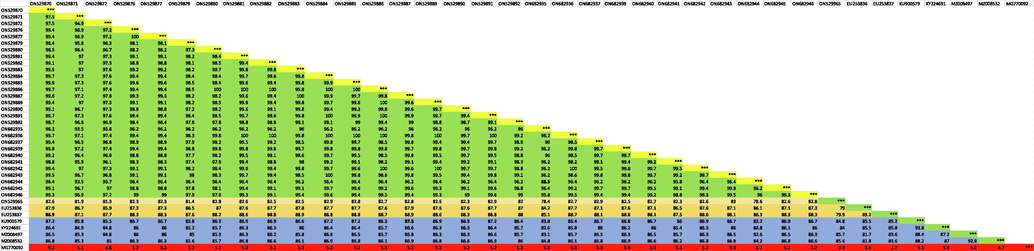

COI gene sequences of 29 samples of A. ochraceus species were analyzed and barcode sequences were submitted into Genbank database with accession numbers ON529870-ON529872, ON529876-ON529877, ON529879-ON529887, ON529889-ON529892, ON682935-ON682937, ON682939-ON682946. Using basic local alignment search tool (BLAST), it was found that the studied samples belong to Hodotermitidae family of termites and there was no COI sequence of A. ochraceus species in the databases but those of two other member of the family Hodotermitidae i.e. Microhodotermes viator (EU253837) (Latreille, 1804) and Hodotermes mossambicus (EU253836) were retrieved from the NCBI database. COI gene sequence of a fruit fly Bactrocera zonata (Saunders, 1842) (MG770092) was used as an outgroup sequence. The sequences of closely species of termites were retrieved in fasta format. Those downloaded sequences along with present research samples sequences were subjected to multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree was constructed using maximum likelihood algorithm. Phylogenetic analysis showed that all the specimens of present study grouped together into a single monophyletic clade, were confirmed to be highly closely related to one another, and proved to be members of the same species. Second closely related clade was the group of different members of genera Microhodotermes and Hodotermes which belong to the family Hodotermitidae. Species of genera Amitermes Silvestri, 1901 and Macrotermes Holmgren, 1910 form separate clades (Fig. 2). Pairwise sequence identity percentage analysis showed that studied samples barcode sequences show 88.5–100% nucleotide sequence identity with one another. This is showing highly conserved nucleotide sequence homology within the collected samples of the A. ochraceus species. Among the sequences retrieved from database M. viator (EU253837) showed highest nucleotide sequence identity of 88.9% with one of present research sample A. ochraceus because M. viator is the member of same family Hodotermitidae. Nucleotide sequence identity with members of other families of termites ranged 82.6–87.3% (Table 2).

Phylogenetic tree was created in MEGA 7.0 software using maximum-likelihood algorithm. The examination shows relationship of COI gene sequences of Anacanthotermes ochraceus with that of other closely related termite species from same family and other families of termites. All termite species used in the phylogenetic tree were labelled by their scientific name along with specific accession number. Numeric values at the base of each branch indicated the percentage of bootstrap value reiterated 1000.

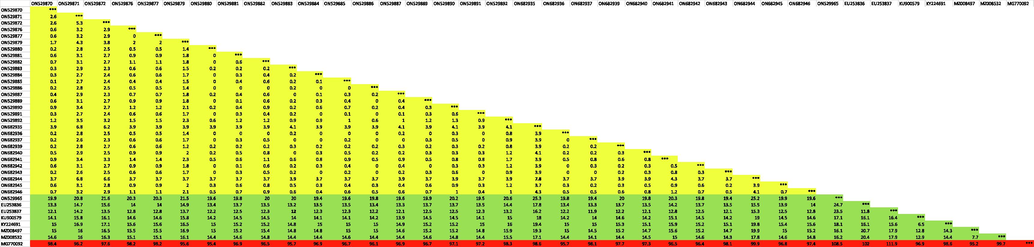

3.2 Intraspecific and interspecific sequence divergence

Degree of sequence divergence at intraspecific as well as interspecific level was studied using MegAlign software application of DNA Star (DNA Star Inc., Madison, WI, USA). A. ochraceus species, 29 samples were analyzed. Intraspecific sequence divergence among studied 29 specimens ranged from 0% to 7.8% indicating low divergence and highly conserved barcode sequence indicating all specimens belong to the same species. Interspecific sequence divergence between studied specimens and other species sequences retrieved from databases showed a high degree of divergence with a minimum interspecific value of 12% with M. viator (EU253837) (Table 3).

4 Discussion

Termites are abundantly present everywhere both in tropical and subtropical regions of the world and exhibit wide genetic diversity (Roy et al., 2006; Cheng et al., 2011). In the past, insect taxonomists were exclusively dependent on the morphological and histological features for the identification of the insect specimens which sometimes might be incorrect and which could lead to revisions of the taxonomic identification and classification of the same organisms. It is also important that specimen can be difficult to identify in different developmental stages (egg, larva, pupa and adult) of sample under study (Hussain et al., 2020). But this present era of the genomics and molecular biology has strengthened the field of taxonomy and systematic identification of species on the basis of DNA sequences (Seifert, 2009). The DNA barcoding has successfully delineated the species borders in insects proving itself a supportive technique for the accurate identification of specimen and discovering new species (Rasool et al., 2020; Sukirno et al., 2020; Wikantyoso et al., 2021; Zaman et al., 2022).

The present study includes 29 COI gene sequences which were amplified with LCO 1490 and HCO 2198 universal primers. These primers have already proved 100% success for insect DNA barcode amplification (Hebert et al., 2003). All the 29 specimens from the given study represented the A. ochraceus species. The sequence analysis of several termite specimens collected from different localities in the Riyadh region confirmed the morphological based identification of the species A. ochraceus, which were previously identified by Sharaf et al., (2021). DNA based identification of soldier caste of genus Coptotermes spp. has been done from Indonesia. The other mitochondrial genes 12S and 16S sequences were used to study phylogenetic relationships and genetic divergence among different species of genus Coptotermes (Wikantyoso et al., 2021). In line with these findings the 29 specimens of A. ochraceus analysis using maximum-likelihood algorithm for phylogenetic study showed highly conserved single clade indicating all specimens belong to same species confirming the morphological studies. Maximum likelihood algorithm has been previously used for phylogenetic relationships of termites by (Bourguignon et al., 2013). Similar results have been reported by Sharma et al., (2013) where several morphological and molecular studies of termites were performed and molecular data confirmed the morphological data. Moreover, the present pairwise nucleotide sequence identity as well as divergence percentage data also confirmed both phylogenetic and morphological information. All specimens identified as same species (intraspecific) showing higher nucleotide sequence identity percentage (88.5–100%) and lower divergence of (0–7.8%). On the other hand, interspecific nucleotide identity was as low as 82.6–87.3% and divergence was as high as 12%. Similar studies also confirmed the genetic divergence of termites at intraspecific as well as interspecific level (Cheng et al., 2011).

The habitat preference of A. ochraceus is remarkably diverse including the various niches in desert habitats (e.g. dead wood, dead date palm fronds, imported wood, dry grass, cartoon bags, dead Acacia, camphora, Cinnamomum and Tamarix, and sheep dung) (Cowie, 1989; Sharaf et al., 2021) which explains the wide geographical distribution records presented in the current study. It is likely that more species will be recorded from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by conducting surveys in poorly collected territories in different seasons and using various collection methods.

5 Conclusions

The specimens of termite species A. ochraceus already identified using morphological traits were revalidated deploying molecular analysis of a mitochondrial gene COI sequence. Molecular data analysis has confirmed morphological identification of all 29 studied samples of A. ochraceus. However, due to limited availability of data about COI barcode sequences about different species of termites in public databases may become hurdle in discovery of new species without the support of morphological data. However, this technology offers strong support for identification of cryptic species which are difficult to identify on the basis of morphological features. Further studies of complete mitogenome can be helpful for accurate identification of termites at species level.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation (MAARIFAH), King Abdul-Aziz City for Science and Technology, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Award Number 13-BIO1410-02).

Ethical Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation (MAARIFAH), King Abdul-Aziz City for Science and Technology, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Award Number 13-BIO1410-02).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbioses, Ecology. Springer Science & Business Media; 2000.

- Species diversity and endemism in the Daphnia of Argentina: a genetic investigation. Zool. J. Linn. Soc.. 2004;140(2):171-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of insecticides against subterranean termites in sugarcane. Int. J. Agric. Biol.. 2006;8(4):508-510.

- [Google Scholar]

- Termites (Isoptera) of Saudi Arabia, their hosts and geographical distribution 1. J. Appl. Entomol.. 1986;101(1–5):413-420.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological identifications of mayflies (Ephemeroptera) using DNA barcodes. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc.. 2005;24(3):508-524.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delineating species boundaries using an iterative taxonomic approach: The case of soldierless termites (Isoptera, Termitidae, Apicotermitinae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.. 2013;69(3):694-703.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence for a higher number of species of Odontotermes (Isoptera) than currently known from Peninsular Malaysia from mitochondrial DNA phylogenies. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20992.

- [Google Scholar]

- The zoogeographical composition and distribution of the Arabian termite fauna. Biol. J. Linn. Soc.. 1989;36(1–2):157-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complete DNA barcode reference library for a country's butterfly fauna reveals high performance for temperate Europe. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.. 2011;278(1704):347-355.

- [Google Scholar]

- Termites in Buildings. Their Biology and Control. Rentokil Ltd; 1986.

- DNA barcodes distinguish species of tropical Lepidoptera. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci.. 2006;103(4):968-971.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. Roy. Soc. London. Ser. B: Biol. Sci.. 2003;270(1512):313-321.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proc. Roy. Soc. London. Ser. B: Biol. Sci.. 2003;270(suppl_1):S96-S99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterfly Astraptes fulgerator. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci.. 2004;101(41):14812-14817.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular identification of sugarcane black bug (Cavelarius excavates) from Pakistan using cytochrome C oxidase I (COI) gene as DNA barcode. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci.. 2020;40(4):1119-1124.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic barcoding and phylogenetic analysis of dusky cotton bug (Oxycarenus hyalinipennis) using mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I gene. Cell. Mol. Biol.. 2017;63(10):59-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barcoding aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) of the Korean Peninsula: updating the global data set. Mol. Ecol. Resour.. 2011;11(1):32-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Demography of coleopterists and their thoughts on DNA barcoding and the Phylocode, with commentary. Coleopt. Bull.. 2005;59(3):284-292.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of mean instead of smallest interspecific distances exaggerates the size of the “barcoding gap” and leads to misidentification. Syst. Biol.. 2008;57(5):809-813.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barcoding bugs: DNA-based identification of the true bugs (Insecta: Hemiptera: Heteroptera) PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18749.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA barcoding of the fire ant genus Solenopsis Westwood (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Riyadh region, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27(1):184-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic differentiation in the soil-feeding termite Cubitermes sp. affinis subarquatus: occurrence of cryptic species revealed by nuclear and mitochondrial markers. BMC Evol. Biol.. 2006;6(1):1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA barcoding applied to invasive leafminers (Diptera: Agromyzidae) in the Philippines. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am.. 2006;99(2):204-210.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cryptic species in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) revisited: we need a change in the alpha-taxonomic approach. Myrmecol. News.. 2009;12:149-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Taxonomy and distribution of termite fauna (Isoptera) in Riyadh Province, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with an updated list of termite species on the Arabian Peninsula. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(12):6795-6802.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic position of Indian termites (Isoptera: Termitidae) with their respective genera inferred from DNA sequence analysis of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase gene subunit I compared to subunit II. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extreme diversity of tropical parasitoid wasps exposed by iterative integration of natural history, DNA barcoding, morphology, and collections. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci.. 2008;105(34):12359-12364.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diversity of red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Oliv. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: studies on the phenotypic and DNA barcodes. International Journal of Tropical Insect. Science. 2020;40(4):899-908.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci.. 2004;101(30):11030-11035.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol.. 1994;3(5):294-299.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA barcoding Australia's fish species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B. 2005;360(1462):1847-1857.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphometric analysis of coptotermes spp. soldier caste (blattodea: rhinotermitidae) in indonesia and evidence of coptotermes gestroi extreme head-capsule shapes. Insects.. 2021;12(5):477.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA barcoding reveals extraordinary cryptic diversity in an amphipod genus: implications for desert spring conservation. Mol. Ecol.. 2006;15(10):3073-3082.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic diversity analysis of chrysopidae family (insecta, neuroptera) via molecular markers. Mol. Biol. Rep.. 2014;41(9):6241-6245.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphometrics, distribution, and DNA barcoding: an integrative identification approach to the genus odontotermes (Termitidae: Blattodea) of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Pakistan. Forests.. 2022;13(5):674.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102782.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: