Translate this page into:

Microwave assisted base-catalyzed 1,3-isomerization of 7-substituted cycloheptatriene bearing electron withdrawing groups

⁎Corresponding author. abdulmajeedsalihhamad@yahoo.com (Abdulmajeed S.H. Alsamarrai)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

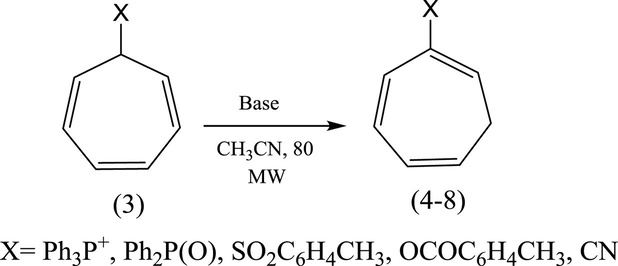

A series of 7-substituted cycloheptatrienes bearing EDG such as (3, X = –PPh3+, –P(O)Ph2, –SO2C6H4CH3, –OCOC6H4CH3 and –CN) were synthesized and their isomerization into the corresponding 2-isomers (4–8) has been achieved, under controlled microwave heating in the presence of easily available DABCO and t-BuOK. On the other hand, the conversion of allyltriphenylphosphonium bromide into vinylic isomer with NEt3 has been carried out in a similar way. This convenient and facile procedure has reduced the average reaction times to a matter of minutes (>20 min), rather than the hours typical of conventional procedures, in addition, the 2-isomers (4–8) were obtained in excellent yields and mechanism of products formation is described.

Keywords

Microwave irradiation

Isomerization

Vinylic phosphonium salt

Substituted cycloheptatriene

1 Introduction

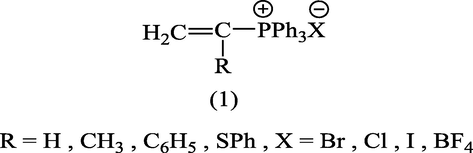

In the last three decades, there has been considerable interest in the reactivity of vinylphosphonium salts such as (1) which is consider as one of the main precursor in the synthesis of carboxylic (Keough and Grayson, 1964; Cory et al.,1980, Cory and Chan, 1975; Darling et al., 1979; Hewson, 1978; Fuchs, 1974), and heterocyclic compounds (Schweizer and Light, 1966; Schweizer and Smucker, 1966; Alsamarrai, 2017; Kuźnik et al., 2017).

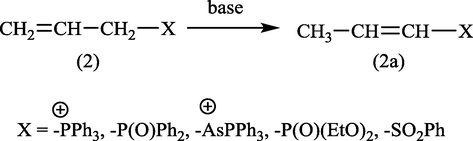

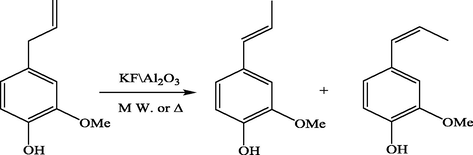

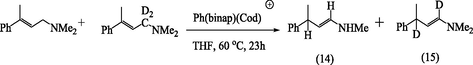

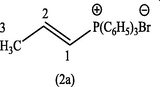

In this respect, the isomerization of allyl, aryl sulphones, allyldiphenylphosphine oxides, diethyl allylphosphonate, allylphosphonium bromide, and allyltriphenyl arsonium bromide such as (2) undergo isomerization to the corresponding vinylic isomers (2a) were achieved by 1,3-proton shift and performed by organic and inorganic bases (Grayson et al., 1959; Swan and Wright, 1971) such as NaH, Et3N, DABCO, pyridine, EtONa, K2CO3 …ets., as it can be seen Fig. 1. Recently, (z)-propenyl ethers were obtained from allyl ethers using lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) as a catalyst and at room temperature (Su and Williard, 2010) Fig. 2.

Conversion of allylic compounds into vinylic compounds.

Conversion of eugenol into vanillin.

In recent years, the application of microwave in organic synthesis has gained increasing attention for the benefit of environment, mildness, and saving of materials. For instance, KF/Al2O3 was introduced as an efficient and versatile catalyst for the isomerization of eugenol into vanillin under heterogeneous reaction conditions and by microwave assistance (Luu et al., 2009) Fig. 3, isomerization of saforle and eugenol were achieved in homogeneous medium under the effect of microwave (Salmoria et al., 1997).

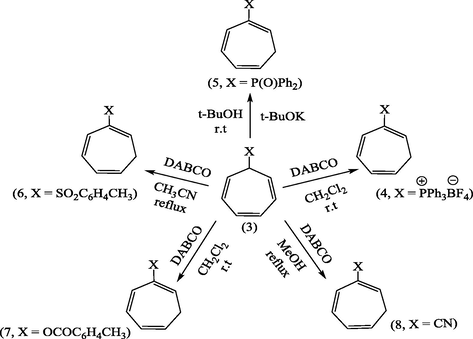

Conversion of (3) into (4–8) under conventional reaction conditions.

However, additional microwave-assisted synthetic processes for the isomerization of allylic acetate prior to a novel intramolecular Diels-Alder cycloaddition to furan gave substituted indole under reaction conditions (Xu and Wipf, 2017).

In continuation of our interest in the development of new approach to the isomerization of (2) and (3) into the corresponding isomers (2a) and (4–8) we reported herein a convenient microwave irradiation approach for this isomerization using NEt3, DABCO, t-BuOK as catalysts.

2 Materials and methods

Melting points were determined on Buchi melting point apparatus using open capillary tube and they were uncorrected. All the required chemicals used were purchased from Aldrich. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on already made 5 × 5 cm plates coated with silica 0.25 cm N-HR/UV254 obtained from Merck. 1H-NMR spectra were recorded on BRUKER spectrometer (300 and 500 MHz) by different solvents with TMS as internal reference. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in ppm relative to TMS as internal standard on the δ scale. IR spectra were recorded on Shimatzu FT-IR-8400S spectrophotometer over a frequency range 4000–400 cm−1. Microwave experiments were conducted using Microwave Synthesis WorkStation (MAS-II), Microwave chemistry technology.

2.1 Preparation of starting materials

Starting materials were prepared as previously reported. The compounds (2) (Keough and Grayson, 1964), (3, X = –+PPh3BF4−) (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000), (3, X = –P(O)Ph2) (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000), (3, X = –SO2C6H4CH3) (Alsamarrai, 2017), (3, X = OCOC6H4CH3) (Alsamarrai, 2014), and (3, X = –CN) (Conrow, 1963).

2.2 Isomerization of allyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (2)

To a solution of allyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (2) (1 g) in dry acetonitrile (5 ml) was added a methanolic solution of (0.1 ml Et3N in 0.4 ml methanol) and irradiated with microwave (500 watt), while the reaction temperature was set up at 80 °C. Examination by TLC showed that the isomerization of (2) to (2a) was completed after 20 min. After cooling, the solvent was removed under vaccuo and the residue was taken up in dichloromethane (10 ml) and washed with 10% aqueous HBF4. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and the solvent was removed under vaccuo again and the remaining crude product recrystallized from ethyl acetate:ether (6:1). The white crystals of propenyl-1-triphenylphosphonium bromide (2a) was collected (Yield: 0.46 g, 46%), m.p., 210–214 °C. [Lit. 213–214] (Grayson and Keough, 1960). The compound (2a) was identified by IR, UV and 1H-NMR. λmax (MeOH): 261.40, 266.40, 272.60 nm; υmax (KBr): 3055 (C—H aromatic), 2950 (C—H aliph), 1589 (C⚌C), 1436 cm−1 (C—P); 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.42 (3H, doublet, CH3), 6.4–7.1 (2H, m, H1,2), 7.5–7.9 (15H, m, C6H5).

2.3 Isomerization of (3, X = –+PPh3BF4−, –P(O)Ph2, –SO2C6H4CH3, –OCOC6H4CH3, and –CN): general procedure

The compounds (3, X = –+PPh3BF4−, –P(O)Ph2, –SO2C6H4CH3, –OCOC6H4CH3, and –CN) (1 g each) were separately dissolved in dry acetonitrile (10 ml) containing catalytic amount of DABCO, except the compound (3, X = –P(O)Ph2) which was dissolved in dry t-butanol containing (30 mg) potassium metal and the mixtures were irradiated under microwave at 500 watt, while the reaction temperature was set up to 80 °C for 15–20 min with one min. interval. The reactions were monitored by TLC. After the isomerization of (3) to (4–8) was completed, the solvents were evaporated and the residues were taken up in dichloromethane (10 ml) each and washed with 10% aqueous HBF4 (10 ml) to remove DABCO and t-BuOk. The organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and the solvents were evaporated to give the crude products of (4–8).

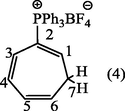

2.3.1 1,3,5-cycloheptatrien-2-phosphonium tetrafluoroborate (4).

The crude product of (4) was dissolved in dichloromethane (10 ml) and precipitated by addition of ether (12 ml) resulting in the separation of pale crystals of 1,3,5-cycloheptatrien-2-phosphonium tetrafluoroborate (4). (Yield : 0.9 g, 90%), m.p., 264–265 °C, [Lit. 262–265 °C] (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000); (Found: C, 67.9; H, 5.3. C25H22BF4P requires C, 68.18; H, 5.0%); λmax (MeOH): 259.80 nm, 265.40 nm, 272.20 nm; υmax (KBr): 3090 (CH-Ar), 3000 (CH-olf.), 2900 (CH-aliph.); 1579.70 (C⚌C-olf). 1436.97 cm−1 (P-Ph); 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.66 (2H, t, J1,7 = J6,7 = 7.5 Hz, H7) 5.65 (1H, d × t, J5,6 1.0 Hz, H6), 6.05 (1H, t × t, JPH1 18.5, J1,7 7.5 Hz, H1), and 6.4–6.7, (2H, m, H4 and H5),7.16 (1H, m, JP,H3 10.5, J3,4 1.0, J3,5 2.0 Hz, H3), 7.5–7.9 (15H, m, C6H5) ppm.

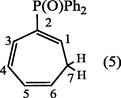

2.3.2 1,3,5-cycloheptatrien-2-yldiphenylphosphine oxide (5).

The deep red residue was passed through an activated alumina column using ether-ethyl acetate (1:2) as eluent. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was recrystallized from ethyl acetate to give 1,3,5-cycloheptatrien-2-yldiphenylphosphine oxide (5). (Yield : 0.63 g, 63%); m.p., 119–120 °C [Lit.120 °C] (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000); (Found : C, 78.0; H, 6.1 C19H17PO requires C, 78.08; H, 5.82%); λmax (EtOH): 261.5, 265, 272 nm; υmax (KBr): 3060 (CH), 1200 cm−1 (P⚌O); 1H-NMR(Toluene-d8) : δ 2.50 (2H, t, H7), 5.50 (1H, d × t, JPH1 17 Hz, H1), 5.90 (1H, m, H6), 6.50 (1H, m, H3), 7.00 (2H, m, J5,6 9 Hz, H4,5), and 7.60 ppm (10H, m, C6H5).

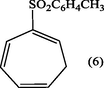

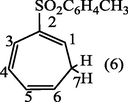

2.3.3 2-Tosylcyclohepta-1,3,5-triene (6).

After the evaporation of the solvent as mentioned earlier the crude residue of (6) was recrystallized from ethanol-H2O (9:1) afforded white crystals of 2-tosylcyclohepta-1,3,5-triene (6). (Yield : 0.87 g, 87%), m.p., 140–142 °C; (Found: C, 68.29; H 5.9. C14H14O2S requires C, 68.29; H, 5.69%); λmax (MeOH); 235.20 nm;υmax (KBr .cm−1); 3075 (CH-aromatic), 2981, 2883 (CH-aliph), 1595(C⚌C), 1560(C⚌C-aromatic), 1145(S⚌O); 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.40 (5H, m, H7 and CH3), 5.45 (1H, d x t, J5,6 9.5 Hz, H6), 6.12 (1H, d × d, J4,5 5.0 Hz, H5), 6.75 (2H, m, H3,4), 7.24 and 7.66 ppm (4H, 2 × d, J 8.0 Hz, aromatic protons).

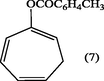

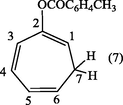

2.3.4 1,3,5-Cycloheptatrienyl-2-toluate (7).

The crude compound (7) was recrystallized from ethanol to give white crystals of 1,3,5-cycloheptatrienyl-2-toluate (7). m.p., 162–4 °C. (Yield: 0.92 g, 92%); λmax (EtOH): 274 nm; υmax (KBr .cm−1): 3079 (CH-aromat.), 2875, 2965 (CH– olef.), 1765 (C⚌O), 1615 (C⚌C aromat.), 1225, 1180 cm−1 (C—O—C); 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.27 (2H, m, H7), 2.3 (3H,CH3) 5.09 (1H, d × t H6), 5.22 (1H,t, H1), 5.24 (1H, m, H4), 6.11 (1H, m, H5), 6.99 (1H, d, H3) 7.49–7.77 ppm (4H, d × d, aromatic protons).

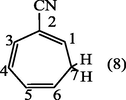

2.3.5 2-cyano-1,3,5- cycloheptatriene (8)

The solvent was evaporated to give brown–oil of 2-cyano-1,3,5- cycloheptatriene (8). (Yield : 0.9 g, 90%); λmax (MeOH); 212 nm, 262.10 nm; υmax (thin film); 3029 (CH-aliph), 2217(C≡N), 1595 cm−1 (C⚌C); 1H-NMR(CCl4) : δ 2.15 (2H, t, J6,7 6.7 Hz, H7), 5.40 (1H, t, J5,6 9.5 Hz, H6), 6.00 (1H, t, H1), 6.25 (1H, d × d, H5), 6.55 (1H, d × d, H4) and 6.8 ppm (1H, d, H3).

3 Results and discussion

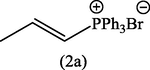

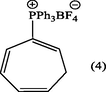

In 2000 and 2017, we were able to introduce DABCO and t-BuOK as an efficient and versatile reagents for the isomerization of 7-substituted cycloheptatrienes bearing EWG groups into the corresponding 2-isomers under homogenous and relatively mild reaction conditions (Alsamarrai, 2017; Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000), see Fig. 3. Almost four decays earlier, Conrow (1963) and Doering et al. (1957) called attention to the usefulness of DABCO in isomerization of (3, X = CN) into (8, X = CN) in a yield of 30% in refluxing methanol for 18 h Fig. 3.

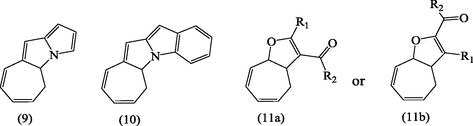

The 2-isomers of 7-substituted cycloheptatrienes bearing EWG such as PPh3+BF4−, P(O)Ph2, SO2C6H4CH3, OCOC6H4CH3, and CN are highly versatile key intermediates in synthesis of heterocyclic compounds under conventional reaction conditions, e.g., compounds (9, 10) (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000) and (11a, b; R1 = R2, Me, Ph or R1 = Me, R2 = Ph) Fig. 4 (Alsamarrai, 2014).

Structures of some heterocyclic compounds.

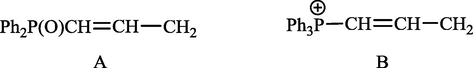

The use of microwave-induced rate acceleration in organic synthesis in comparison to the conventional solution phase reactions was first introduced in 1993 by Loupy and Thach with their investigation of the base- catalyzed isomerization of eugenol (Loupy and Thach, 1993). As a part of our ongoing research into the chemistry of isomerization of 7-substituted cycloheptatrienes, we introduced microwave technology for the isomerization of these compounds toward the corresponding 2-isomers. The starting compound (2) (Keough and Grayson, 1964; Grayson and Keough, 1960) was obtained by reaction of triphenylphosphine with allyl bromide in dichloromethane while the other starting compounds (3, X = +PPh3BF4− (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000), P(O)Ph2 (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000), SO2C6H4CH3 (Alsamarrai, 2017), OCOC6H4CH3 (Alsamarrai, 2014) and CN (Conrow, 1963) were obtained by reaction of triphenylphosphine, methyl diphenylphosphinite, p-toluenesulphinic acid sodium salt, sodium toluate, and sodium cyanide, respectively with tropylium fluoroborate in dichloromethane and methanol as indicated in Fig. 3. The final target compounds (2a, 4–8) were synthesized by isomerization of (2) and (3, X = –+PPh3BF4−, –P(O)Ph2, –SO2C6H4CH3, –OCOC6H4CH3, and –CN) in CH3CN and t-BuOH with DABCO, t-BuOK, and NEt3. DABCO, t-BuOK, and NEt3 proved to be an efficient and versatile reagents under the assistance of microwave irradiation (500 watt) and could perform the isomerization within 15–20 min. whereas the same reactions required 18–24 h by conventional procedures (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000). All reaction were carefully monitored by TLC. Thus, it appeared that the isomerization reactions in all cases showed no traces of starting materials and indicated the formation of only single product. After the removal of the bases (aqueous HBF4), solvents, and purification, assignment of the structures (2a, 4–8) were based on changes in the UV, IR and 1H-NMR spectra; the UV exhibited several bands differing markedly from that of the original starting materials (3, X = +PPh3BF4−) (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000), P(O)Ph2 (Alsamarrai and Hobson, 2000), SO2C6H4CH3 (Alsamarrai, 2017), OCOC6H4CH3 (Alsamarrai, 2014) and CN (Conrow, 1963). The 1H-NMR data (Table 2) showed, the presence of five olefinic protons and a CH2 group adjacent to an olefinic proton coupled to phosphorus through a double bond, i.e., the moieties A and B in compounds (4,5). Upon irradiation of the CH2 signals at 2.66 and 2.50 ppm in compounds (4) and (5) respectively, the signals due to the 6-proton collapsed to a doublet due to coupling between H5 and H6, and the 1-proton also collapsed to a doublet due to coupling between phosphorus and H1, thus confirming the structures (4,5). Details of the characterization of the compounds (2a) and (4–8) reported in the experimental part.

The conversion of (2) into (2a) gave only a moderate yield of the product (46%). The big evidence for the formation of (2a) was come from its 1H-NMR spectrum which indicates the presence of a doublet at 2.42 ppm corresponding to CH3 coupled to an olefinic proton (H2) and a multiplet at 6.4–7.1 ppm for H1 and H2.

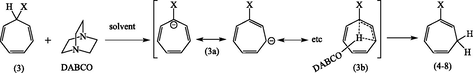

The isomerization presumably occurred via the cycloheptatrienide (3a) as illustrated in Fig. 5. In view of the instability of cycloheptatrienide anion (3a) (Dauben and Rifi, 1963), it seemed somewhat surprising that isomerization proceeded so readily and with relatively mild bases (pka1 and pka2 of DABCO: 2.95 and 8.60 respectively). Moreover, attempts to observe Wittig reactions under these conditions, e.g., using a reactive carbonyl compound such as benzaldehyde particularly with 7-isomers bearing phosphonium and phosphoryl groups, failed to provide any evidence for the formation of the cycloheptatrienide (3a) as an independent species. It seemed likely that the proton transfer leading to the isomers (4–8) occurred within a complex formed from (3a) and a molecule of DABCO.

Proposed mechanism for the conversion of (3) to (4–8).

Similarly, a complex intermediate between DABCO and allylphosphonium bromide (2) would lead to the isomer (2a). Thus, the formation of the 2-isomer, e.g., (4, X = +PPh3BF4−) and the total absence of any deuterated product indicated that the hydrogen shift was intramolecular process (Hunter and Cram, 1964) involving a partially anionic species (3b).

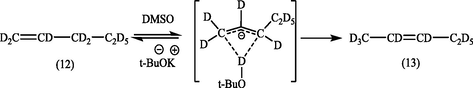

Earlier, such an intramolecular mechanism has been suggested by Bank et al. (1963) for the isomerization of perdeuterio-1-pentene (12) to perdeuterio-2-pentene (13) in dimethyl sulphoxide in the presence of 2-methyl-1-pentene. It was found that when 18% of the deuterium had been lost from the pentene olefin, less than 0.4% deuterium had been incorporated in the 2-methyl-1-pentene or 2-methyl-2-pentene. These intramolecular 1,3-prototropic shifts are not uncommon in β,α-unsaturated compounds (Hunter and Cram, 1964).

Later, a careful investigation of the reaction products (14) and (15) by 1H-NMR and GC–MS analyses showed the absence of mono-deuterated products as it can be seen in the equation below (Tani, 1985). Therefor it is concluded that the present isomerization proceeds exclusively via intramolecular 1,3-hydrogen migration.

In general, the irradiation with microwave resulted in an improved yields and the reaction times were remarkably reduced (Table 1). The outcomes of these reactions are inconsistent with mechanism proposed that the high activation energy of the process could be responsible for the observed improvement under microwave irradiation (Rodriguez and Prieto, 2016).

2-Isomers

Solvent

m.p. °C

Temp. °C

Time/min.

Catalyst

Yield%

CH3CN

210–214

80

20

Et3N + MeOH

46

CH3CN

264–265

80

15–20

DABCO

90

t-BuOH

119–120

80

15–20

DABCO

91

CH3CN

140–142

80

15–20

DABCO

87

CH3CN

162–164

80

15–20

DABCO

92

CH3CN

----

80

15–20

DABCO

90

2-Isomes

H1

H2

H3

H4

H5

H6

H7

6.40–7.10

2.42 d CH3

6.05 t × t

7.16 m

6.4–6.7 m

5.65 d × t

2.66 t

5.50 d × t

6.50 m

7.00 m

5.90 d × d

2.50 t

6.46

6.75 m

6.12 d × d

5.45 d × t

2.40 m

5.22 t

6.99 d

5.24 m

6.11 m

5.09 d × t

2.27 m

6.0 t

6.8 d

6.55 d × d

6.25 d × d

5.4 t

2.15 t

4 Conclusions

7-Substituted cycloheptatrienes bearing EWG groups and their 2-isomers are of interest, partly due to their occurrence in natural products, and partly due to their theoretical synthetic utility involving either 7-substituted cycloheptatrienes (3) or prior isomerization to potentially electrophilic α,β-unsaturated derivatives (4–8). This work conforms the usefulness of microwave as easy, highly yield method, for the isomerization of (3) to the corresponding 2-isomers (4–8) under microwave irradiation. We can reveal that this isomerization proceeds via intramolecular 1,3-hydrogen migration. The process proved to be successful and yields reach to 92% and with short reaction times (>20 min). The simple experimental procedure and easy purification make this protocol advantageous.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to department of chemistry, college of education, University of Samarra, Iraq, for funding this project. Also, authors thank SDI (Samarra Drug Industry) for providing some instrumental facilities.

References

- Synthesis of novel heterocyclic compounds by nucleophilic addition of reaction of nitrogen nucleophiles to 2-cycloheptatrienyltriphenyl phosphonium fluroborate. J. Jordon. Appl. Sci.. 2000;2:54-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of 2-(p-toluenesulphonyl) tropane-2-ene: Anhydroecgonine analog. Phosphorus, Sulfur, Silicon Relat. Elem.. 2017;192:252-254.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alsamarrai, R.T.M., 2014. Synthesis of furan derivatives fused to cycloheptatdiene ring from 1,3-dicarbonyl and substituted phosphonium salt of cycloheptatriene (MSc Dissertation). College of appl. Sci., Univ. of Samarra, Iraq.

- Anionic activation of CH bonds in Olefins. VI. Intramolecular nature and kinetic isotope effect of base-catalyzed olefin isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 1963;85:2115-2118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conrow, K., 1963. Org. Synthesis 1963. Tropylium fluoborate Conrow, Kenneth Organic Synthesis. 43, 101–104.

- Vinyl phosphonium bicycloannulation of cyclohexenones and its use in a stereoselective synthesis of trachyloban-19-oic acid. J. Org. Chem.. 1980;45:1852-1863.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bicycloannulation: a one-step synthesis of tricyclo [3.2. 1.02, 7] octan-6-ones. Tetrahedron Lett.. 1975;16:4441-4444.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enolate alkylations with diethylbutadiene phosphonate-II. Tetrahedron Lett.. 1979;20:2761-2762.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reactions of the cycloheptatrienylium (tropylium) ion. J. Am Chem. Soc.. 1957;79:352-356.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trans-1-butadienyltriphenylphosphonium bromide: a reagent for the 1, 3-cyclohexadienylation of carbonyl groups. Tetrahedron Lett.. 1974;15:4055-4058.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phosphonium compounds. II. Decomposition of phosphonium alkoxides to hydrocarbon, ether and phosphine oxide. J. Am. Chem Soc.. 1960;82:3919-3924.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phosphonium compounds. I. Elimination reactions of 2-cyanoethyl phosphonium salts. Asymmetric phosphines and alkylenediphosphines. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 1959;81:4803-4807.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of triphenyl-1-phenylthiovinyl phosphonium salts and use for preparation of cyclopentanones. Tetrahedron Lett.. 1978;19:3267-3268.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrophilic substitution at saturated carbon. XXIII. Stereochemical stability of allylic and vinyl anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 1964;86:5478-5490.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phosphonioethylation. Michael addition to vinylphosphonium salts1. J. Org. Chem.. 1964;29:631-635.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vinylphosphonium and 2-aminovinylphosphonium salts–preparation and applications in organic synthesis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem.. 2017;13:2710-2738.

- [Google Scholar]

- Base-catalysed isomerization of eugenol: solvent-free conditions and microwave activation. Synth. Commun.. 1993;23:2571-2577.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fast and green microwave-assisted conversion of essential oil allylbenzenes into the corresponding aldehydes via alkene isomerization and subsequent potassium permanganate promoted oxidative alkene group cleavage. Molecules. 2009;14:3411-3424.

- [Google Scholar]

- New insights in the mechanism of the microwave-assisted Pauson-Khand reaction. Tetrahedron. 2016;72:7443-7448.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isomerization of safrole and eugenol under microwave irradiation. Synth. Commun.. 1997;27:4335-4340.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reactions of phosphorus compounds. VIII. Preparation of pyrrolizidine compounds from vinyltriphenylphosphonium bromide. J. Org. Chem.. 1966;31:870-872.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reactions of phosphorus compounds. XI. A general synthesis of substituted 1, 2-dihydroquinolines. J. Org. Chem.. 1966;31:3146-3149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isomerization of allyl ethers initiated by lithium diisopropylamide. Org. letts.. 2010;12:5378-5381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organophosphorus compounds. IX. Vinylphosphonium salts as reagents for proteins. Australian J. Chem.. 1971;24:777-783.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asymmetric isomerization of allylic compounds and the mechanism. Pure Appl. Chem.. 1985;57:1845-1854.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indole synthesis by palladium-catalyzed tandem allylic isomerization–furan Diels-Alder reaction. Org. Biomol. chem.. 2017;15:7093-7096.

- [Google Scholar]