Translate this page into:

Metallo-β-lactamases producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the molecular mechanism of drug resistance variants

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Majmaah University, Majmaah 11952, Saudi Arabia. m.palanisamy@mu.edu.sa (Palanisamy Manikandan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background

Metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) type carbapenemases are produced by pathogenic Pseudomonas spp. and exhibit carbapenemase activity. The study will look into drug resistance and the molecular mechanisms of drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa variants.

Methods

A total of 74 P. aeruginosa strains were isolated from urine, pus, sputum, blood, throat swab, Foley’s catheter, and nasal swab. The isolates were screened for antibiotic susceptibility and the identified MDR strains were further tested for β-lactamase production. Multiplex PCR was used to identify the presence of mcr-1 and blaNDM-1 genes in MDR organisms. The minimum inhibitory concentration for ceftazidime and colistin was also determined, in addition to the biofilm inhibitor activity. Confocal microscopy was used to determine the production of biofilms.

Results

The isolated P. aeruginosa strains exhibited antibiotic resistance to aminoglycosides (amikacin and gentamicin). Fifty three percent of the isolated P. aeruginosa strains produced metallo-β-lactamase and the remaining isolates were non-metallo-β-lactamase type (46.8 %) (p < 0.0001). The MIC value of β-lactamase producers against colistin ranges from 0.5 µg/mL to 6 µg/mL. The MDR bacteria exhibited mcr-1 and blaNDM−1 genes. The MDR P. aeruginosa strain treated with colistin and ceftazidime inhibited initial biofilm formation. These combination of antibiotics effectively prevented initial biofilm development than individual antibiotics (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The current analysis detected MDR among P. aeruginosa isolates that carried drug-resistant genes.

Keywords

β-lactamase gene

Multidrug resistance

Biofilm

Adaptive mechanisms

Drug-resistance genes

1 Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a non-fastidious and ubiquitous bacterium that grows rapidly in wet or humid environments. This is considered one of the opportunistic pathogenic bacteria that generally abundant among diabetes cases, immune-compromised patients, bloodstream, sepsis, indwelling devices, soft tissue infections, including burns, and skin surface (Olasehinde and Lamikanra, 2021). To prevent resistance, various frontline antibacterial agents are prescribed to treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. P. aeruginosa is a biofilm-forming bacterium that escapes from the antibiotic treatment to the site of infection and promotes interactions on the cell surface for the degradation of tissues. Biofilm formation is an adaptive mechanism of bacteria in the P. aeruginosa and it resists bacteria from external stress, and improves colonization, persistence and adaptation, through aggregation of biomolecules (carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids) and exopolysaccharides induced by poly-N-acetylglucosamine (Brindhadevi et al., 2020). In P. aeruginosa, low membrane permeability and multi-drug efflux system are the major factors which are associated with broad substrate specificity and several genetic domains involving multi-drug resistance (MDR) (Zahedani et al., 2021). In P. aeruginosa, increased virulence factors are involved in disease morbidity, with activation of hemolysin that causes tissue damage, red cell destruction and dysfunctional cellular immune responses. Production of extracellular enzymes such as lipases and proteases by biofilm-producing bacteria improves pathogenicity thus assisting the invasion of host cells, affecting host defense mechanisms leading to mammalian tissue damage. The virulent proteins secreted by the pathogenic strains affect lipid membranes resulting in the intracellular survival of pathogenic strains and degradation of lipids leading to tissue damage. Antibiotic resistance mechanism mediated by biofilm formation and efflux pump among P. aeruginosa has been reported previously by various research groups (George et al., 2022).

Metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) type carbapenemases are produced by various pathogenic Pseudomonas spp., and these types of bacteria exhibitcarbapenemase activity. Among Pseudomonas strains various types of MBLs such as Imipenemase (IMP), Sao Paulo Metallo-beta-lactamase (SPM), Verona imipenemase (VIM), Florence imipenemase (FIM), Adelaide IMipenmase (AIM) and New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) have been reported (Acharya et al., 2017). Moreover, NDM type is predominant among P. aeruginosa strains and the gene is associated with plasmid contributing to increased disease outbreaks (Shahin and Ahmadi, 2021). Recently, the prevalence of antibiotic resistance, especially colistin-resistant to P. aeruginosaincreased significantly. Among P. aeruginosa strains the increased colistin resistance was associated with a gene or chromosomal mutation and the presence of the mcr gene was detected (Lin et al., 2016). The transformation of the mcr gene from pathogenic bacteria to other organisms through plasmid was described previously.mcr-1 is the most important prevalent marker among the pathogenic strains, moreover, other types of mcr genes (mcr2 – mcr-9) were also reported among P. aeruginosa (Shahin and Ahmadi, 2021). P. aeruginosa uses an efflux pump due to the presence of MexAB-OprM and this mechanism mediated the development of various classes of antibiotics, including, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, β-lactam, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, novobiocin, macrolides, and sulphonamides (Gautam et al., 2020). P. aeruginosa is involved in nosocomial infections and the analysis of specific genetic material of the Metallo β-lactamase gene is helpful in analyzing the association with other genes involved in drug resistance and identifying the routes of transmission. The MBL-producing P. aeruginosa carries blaNDM-1 gene and has been reported previously. Although various new lactam drugs with potential antimicrobial spectrum, potential antimicrobial activity, and effective drugs beings developed to control Gram-negative bacteria, P. aeruginosa often develops various drug-resistant mechanisms against carbapenem-type drugs. In addition to various drug-resistant mechanisms, the developed bacterial biofilm prevents the activity of antibiotics (Pan et al., 2016). This study analyzed the genes associated with antibiotic resistance, drug resistance mechanisms, and P. aeruginosa biofilm production.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Strains

The study included 74 P. aeruginosa isolates from various clinical specimens. Sample types include urine, pus, sputum, blood, throat swab, Foley's catheter, and nasal swab. Samples showing evident signs of contamination have been excluded from the study.

2.2 Isolation and identification of P. aeruginosa

Samples were streaked onto blood agar and MacConkey agar plates, and they were incubated for twenty-four hours at 37°C. After additional subculturing, the verified P. aeruginosa isolates were identified using colony morphology and biochemical characteristics. The confirmed P. aeruginosa isolates were further subcultured and identified using colony morphology and biochemical features. The development of pyocyanin pigmentation was observed on nutrient agar plates. To purify P. aeruginosa strains, the colonies were subcultured on cetrimide agar medium, incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and fluorescein production was observed (Chawla et al., 2013).

2.3 Antimicrobial susceptibility

Antibiotic susceptibility of the isolated strains was carried out using Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method as described previously. The antibiotics such as amikacin (AK, 10 μg), aztreonam (AT, 30 μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 μg), cefepime (CPM, 30 μg), colistin (CL, 10 μg), imipenem (IPM, 10 μg), ofloxacin (OF, 30 μg),gentamicin (GEN, 30 μg), piperacillin-tazobactam (PIT), piperacillin (PI, 30 μg), levofloxacin (LEV, 30 μg) and meropenem (MRP, 10 μg) were used. Bacteria that were resistant to > 3 antimicrobial classes were considered MDR (Arasu et al., 2019).

2.4 Analysis of bacteria for MBL production

The MBL-producing multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains were determined as described previously. The strains were tested using the Imipenem- EDTA combined disc test. Two imipenem discs were placed on Mueller Hinton Agar medium and 5 μL EDTA was loaded on one disc and the plate was incubated for 18 h at 37°C. After 18 h, the susceptibility of the imipenem-EDTA disc was compared with the imipenem disc (Deshmukh et al., 2011).

2.5 Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

Colistin was used for the determination of MIC by broth dilution method as described earlier. The colistin resistance pattern was detected among the isolated P. aeruginosa strains using standard colistin (Abdullah Al-Dhabi et al., 2015).

2.6 Detection of mcr-1 and blaNDM−1

MDR strains of P. aeruginosa were subjected to the extraction of DNA using the phenol chloroform method as described by the manufacturer instructions. The amount of DNA was quantified using a nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The drug-resistant genes (mcr-1 and blaNDM-1) were determined using the forward (CGGTCAGTCCGTTTGTTC and GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC) and reverse (CTTGGTCGGTCTGTAGGG and CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC) primers (Gurung et al., 2020).

2.7 Analysis of biofilm production by P. aeruginosa strains

Biofilm-production test was performed using the micro titer plate method as described earlier. About 350 µL of nutrient broth and 50 µL inoculums were introduced in a microtiter plate and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After 24 h, the developed biofilm was fixed and stained with crystal violet. The negative control (P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853) was used for analysis. The isolates were categorized as non-, weak-, moderate- and strong-biofilm producers (Santos et al., 2023).

2.8 Synergistic activity of antibiotics on initial adhesion of P. aeruginosa

The effect of antibiotics or combinations was selected for initial inhibition of bacterial cell adhesion to microtiter plates. Briefly, the isolated MDR P. aeruginosa was grown for 12 h and the optical density was observed at 600 nm. The culture was incubated up to reach 1.0 OD at 600 nm. Nutrient broth medium (270 µL), 10 µL bacterial culture and 20 µL of diluted antibiotic or combinations were added into each well. It was allowed for 1 h for attachment to polystyrene-coated plates. The non-adherent cells were removed and fixed with 99 % methanol. It was further stained with 100 µL crystal violet and excess stains were removed. The wells were flooded with 33 % glacial acetic acid (300 µL) and the absorbance was read at 600 nm. To the negative control antibiotic/combinations were not incorporated.

2.9 Biofilm inhibitory effect of antibiotics

The combined effect of colistin and ceftazidime on biofilm inhibitory effects was studied. The 18 h P. aeruginosa culture broth (120 µL) (104 CFU/mL and 106 CFU/mL) was inoculated into nutrient broth medium (300 µL) containing various concentrations of antibiotics (10 – 50 µM). The microtiter plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and the biofilm formation was determined after crystal violet staining (Sandasi et al., 2008).

2.10 Antibiofilm activity of antibiotics and confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis

Biofilm-producing Pa-1 strain was used for this assay. Briefly, biofilm-producing bacterium was inoculated into 24 well microtiter plates. About 1 mL bacterial suspension was added and incubated for 24 h and renewed with culture medium. Then the wells were treated with 0.1 mL antibiotic and distilled water was added to the control (Djordjevic et al., 2002). After 48 h treatment, the biofilm formation was assayed using a confocal laser scanning microscopy.

2.11 Statistical analysis

The results were the average of three different experiments. The final data were analyzed using SPSS (version 18) software. One-way analysis of variance was performed and the significance level was assessed (p < 0.05).

3 Results

3.1 P. aeruginosa population in the samples

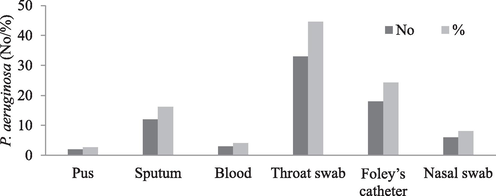

In total, 74 P. aeruginosa strains were identified and included in the study from various clinical specimens. The throat swab was the most common sample, yielding 44.6 % of the isolates (33 nos.) (Fig. 1).

Presence of P. aeruginosa isolates from different clinical samples.

3.2 Drug resistance pattern of P. aeruginosa

A total of 74 P. aeruginosa colonies were detected and tested against different classes of antibiotics to identify the drug-resistance pattern. The isolated P. aeruginosa strains exhibited maximum susceptibility to piperacillin-tazobactam (β-lactam inhibitor) (n = 65, 87.85 %), imipenem (carbapenem) (n = 61, 82.45 %), and meropenem (carbapenem) (n = 59, 79.65 %). The isolated strain exhibited antibiotic resistance to aminoglycosides (amikacin and gentamicin). They presented increased resistance to fluroquinolones such as ofloxacin (n = 47, 63.45 %), ciprofloxacin (n = 45, 60.75 %) and levofloxacin (n = 41, 55.35 %) (Table 1).

Resistance

Intermediate

Susceptible

Antibiotics

n (%)

n (%)

n (%)

Amikacin

21 (25.35)

0

53 (71.65)

Aztreonam

17 (22.95)

1 (1.35)

56 (75.6)

Ceftazidime

10 (13.5)

0

64 (86.5)

Ciprofloxacin

45 (60.75)

5 (6.75)

24 (32.4)

Cefepime

24 (32.4)

0

50 (67.6)

Imipenem

13 (17.55)

0

61 (82.45)

Ofloxacin

47 (63.45)

11 (14.85)

16 (21.6)

Gentamicin

20 (27)

0

54 (73)

Piperacillin-tazobactam

9 (12.15)

0

65 (87.85)

Piperacillin

15 (20.25)

7 (9.45)

52 (70.2)

Levofloxacin

41 (55.35)

1 (1.35)

32 (43.2)

Meropenem

11 (14.85)

4 (5.4)

59 (79.65)

3.3 Analysis of MBL- producing P. aeruginosa and the effect of colistin

Metallo-β-lactamase was produced by over half of the isolates (53.2 %), while non-metallo-β-lactamase types accounted for 46.8 % of the isolates (p < 0.0001). There were notable differences in the generation of β-lactamase (p < 0.0001). Forty β-lactamase strains were selected from among the strains and their MIC values were determined. The MIC value of colistin ranges from 0.5 µg/mL to 6 µg/mL. A total of 33 % of strains presented 0.5 µg/mL, 57.65 % of strains presented 3 µg/mL, and 9.35 % presented 6 µg/mL.

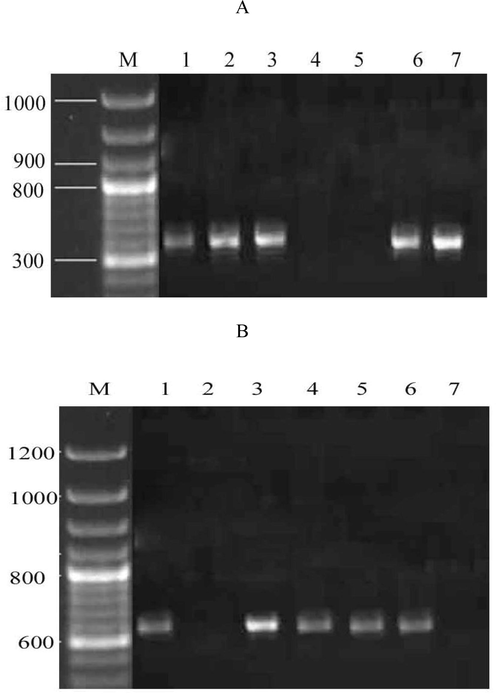

3.4 Determination of mcr-1 and blaNDM−1

The isolated bacterial strains that exhibited maximum tolerance to colistin (6 µg/mL MIC) were subjected to the determination of mcr-1 and blaNDM−1 genes. In this study, the prevalence of the mcr-1 gene was detected from the MDR P. aeruginosa. Among the seven selected bacteria, five strains exhibited the mcr-1 gene. The strains 4 and 5 were mcr-1 negative and the result was depicted in Fig. 2A. In addition, except the strains 2 and 7, other MDRs presented the blaNDM−1 gene. In strain 3, the expression level of the blaNDM−1 gene was higher than other strains (Fig. 2B). These MDR P. aeruginosa strains 1, 2, 3 were isolated from the nasal swab and 4, 5 were isolated from pus. The strains 6 and 7 were isolated from the throat swab.

Agarose gel electrophoresis shows the presence of drug resistance genes in MDR P. aeruginosa. mcr-1 gene was amplified using specific primers (A), blaNDM−1 gene from the MDR P. aeruginosa (B). Lane M represents the DNA ladder and wells 1–7 denote MDR strains 1–7.

3.5 Biofilm-producing P. aeruginosa strains

A biofilm-producing bacterial strain was screened among MDR P. aeruginosa and the result was compared with non-biofilm-producing control. The biofilm-producing potential was classified into weak, moderate and strong biofilm producers. Among the seven MDR bacterial strains, MDR-Pa-1 exhibited maximum biofilm-producing properties and the optical density of the developed biofilm was higher than other strains. Four isolates produced strong biofilms, two were moderate, and one strain produced weak (Table 2).

Bacteria

Biofilm-properties

OD value

p-value

MDR-Pa1

Strong

>1.3

<0.001

MDR-Pa2

Moderate

0.148 ± 0.286

<0.05

MDR-Pa3

Strong

>1.5

<0.001

MDR-Pa4

Weak

0.015 ± 0.063

<0.05

MDR-Pa5

Strong

>1.05

<0.001

MDR-Pa6

Strong

>1.429

<0.001

MDR-Pa7

Moderate

0.248 ± 0.316

<0.05

Control

Nil

0.009 ± 0.02

0.0

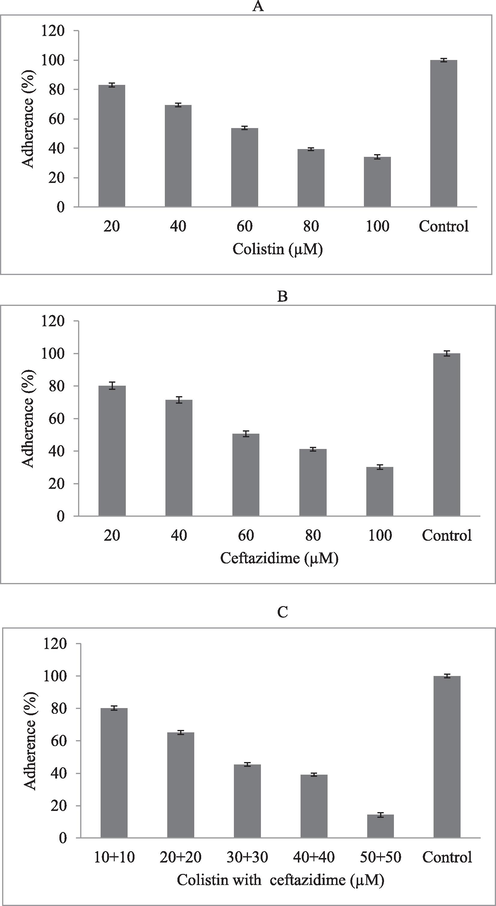

3.6 Effect of colistin with ceftazidime on initial adhesion of P. aeruginosa

In bacterial pathogens, initial adhesion on the substrate is an important step for biofilm development. In this study, the role of colistin, ceftazidime and synergistic activity of colistin and ceftazidime were analyzed. At 20 µM colistin concentration, biofilm adhesion was 83.1 ± 1.3 %. At 100 µM concentration, colistin effectively inhibited initial adhesion on the polystyrene plate than control (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). The broth culture treated with ceftazidime prevented initial adhesion on the polystyrene plate (Fig. 3B). The antibacterial effect was dose-dependent and improved effect was achieved at 100 µM concentration. The combined effect of colistin with ceftazidime was analyzed and improved initial inhibition of biofilm development was achieved than individual antibiotics (p < 0.001). The combined antibiotic treatment (colistin or ceftazidime) showed only 14.3 ± 1.4 % adhesion at 50 µM concentration (Fig. 3C).

Inhibitory effect of colistin and ceftazidime and synergistic activity on P. aeruginosa. inhibitory effect of colistin (A), ceftazidime (B), and combined effect (C) in vitro.

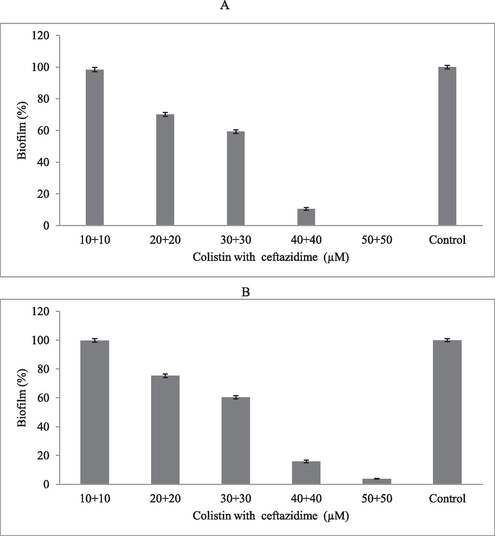

3.7 Biofilm inhibitory effect

Colistin combined with ceftazidime has potential biofilm inhibitory activity in P. aeruginosa. These antibiotics inhibited biofilm formation in microtiter plates inoculated with P. aeruginosa at two different concentrations (104 CFU/mL and 106 CFU/mL). The biofilm inhibitory effect was influenced by inoculum concentration, and at higher inoculums concentration, the maximum antibiotic effect was achieved due to increased bacterial growth (p < 0.05). At 50 µM antibiotic concentration, 100 % biofilm inhibitory effect was achieved at 104 CFU/mL inoculum, and > 95 % biofilm inhibitory effect was achieved at 106 CFU/mL inoculum (Fig. 4A and B).

Biofilm inhibitory effect of colistin and ceftazidime at various concentrations in microtiter plates. P. aeruginosa was cultured in the nutrient broth medium containing antibiotics at 104 CFU/mL (A) and 106 CFU/mL (B) cell densities.

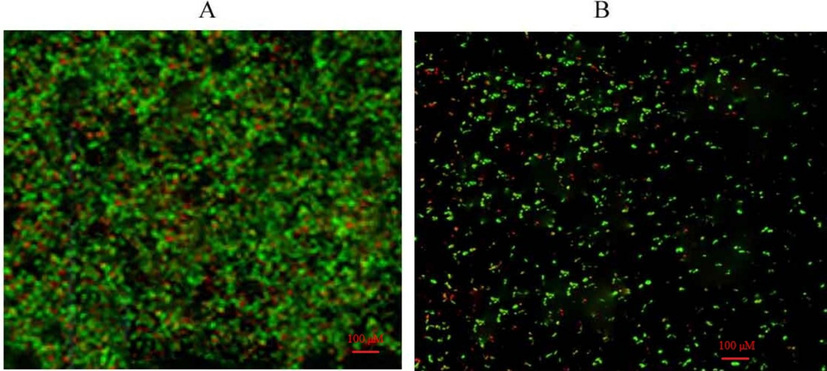

3.8 Determination of biofilm

A confocal microscopy was used to determine P. aeruginosa biofilm formation. The antibiotics reduced the number of live bacterial cells in the biofilm. Biofilms treated with colistin combined with ceftazidime reduced viable bacterial cells after 24 h of incubation. Biofilm inhibition was analyzed and surface scanning was performed using confocal microscopy. The surface layer with 40 – 80 μm thickness biofilm was observed using confocal microscopy. The antibiotics-treated biofilm presented live and dead cell layers within the extracellular matrix. The present finding revealed biofilm-producing property of P. aeruginosa and the combined effect of colistin and ceftazidime on biofilm. The control biofilm appears dark green colour. The biofilm treated with the combination of colistin and ceftazidime reduced live cells and induced cell death (Fig. 5).

Confocal microscopy analysis of P. aeruginosa biofilm and synergistic activity of antibiotics. Microcolonies in the control biofilm (A) and less compact colonies of P. aeruginosa under aerobic conditions after treated with colistin and ceftazidime (B).

4 Discussion

Antimicrobial resistance is a major threat to patient safety, mainly in the hospital environment. In the hospital environment, the admitted patients are highly susceptible to colonization of drug-resistant bacteria due to continuous hospitalization, prolonged exposure to drugs and implementation of various invasive therapeutic protocols. These risk factors lead to increased infection rates, the increased dose or generation of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and the minimum efficacy of antimicrobial drugs. The metallo-β-lactamase producing bacterial strains are resistant to various antibiotics, including carbapenems, these drugs are considered as the final resort to treat Gram-negative bacterial infections. In addition, metallo-β-lactamase producing bacterial strainsdevelops the drug-resistant phenotype to multidrug, because they acquired drug-resistant genes and originate from nosocomial infections (Lagatolla et al., 2004). These metallo-β-lactamase producing bacterial strains pose a serious challenge to antibiotic chemotherapy because most of the strains produce bacterial biofilm. In the present study, 74 P. aeruginosa strains were isolated from the sample and antibiotic resistance was analyzed. The isolated strain exhibited maximum antibiotic resistance to aminoglycosides (amikacin and gentamicin). The present study revealed that the carbapenem-resistant MDR P. aeruginosa strains produce carbapenemase (MBL type). Among the 74 clinical isolates, 53.2 % produced metallo-β-lactamase and the remaining isolates were non-metallo-β-lactamase type (46.8 %). The prevalence of metallo-β-lactamase producing strains revealed an increased rate of carbapenem resistance among the isolated strains.

The rate of carbapenem resistance P. aeruginosa varied based on geographic region, source of specimen, types of infection and selective pressure due to antimicrobials (Morrow et al., 2013). In a study, Meradji et al. (2015) reported a reduced rate (18.75 %) of carbapenems degrading P. aeruginosa. The P. aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients exhibited an increased rate of carbapenem-resistant and enzyme production was reported (Mirsalehian et al., 2017). In a study, Farajzadeh Sheikh et al. (2014) reported multiple-drug resistance P. aeruginosa with 58.7 % resistant to imipenem and 31.8 % resistance to meropenem. In our study, we detected increased drug resistance among carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa than non-carbapenemase producing organisms. The isolated strains showed susceptibility to colistin and the MIC value of colistin ranges from 0.5 µg/mL to 6 µg/mL. These results revealed that colistin become the final resort for multi-resistant P. aeruginosa strains. Various phenotypic characters have been used to screen MBL production and the double-disk synergy test, MBL Etest and β-lactam substrates were used for screening (Inacio et al., 2014). In our study, the prevalence of mcr-1 and blaNDM−1 gene were detected from the MDR P. aeruginosa. Among the seven selected biofilm-forming bacteria, all five strains exhibited mcr-1 gene. In addition, except the strains 2 and 7, other MDR presented blaNDM−1 gene. In strain 3, the expression level of the blaNDM−1 gene was higher than the other strains. These MDR P. aeruginosa strains were isolated from the nasal swab and pus. The presence of blaNDM in P. aeruginosa strain was reported earlier and in our study two bacterial strains were negative for the blaNDM gene. These findings revealed that the isolated bacterial strains have other drug-resistant mechanisms, such as up-regulation of efflux pumps, oprD outer membrane protein-encoding gene and production of other carbapenemases. In a study, Haghi et al. (2017) reported MDR-PA with blaNDM-1 genes isolated from Iran. In certain cases, prolonged hospital stay and urinary tract infections positively influenced MBL-positive P. aeruginosa infections (Lucena et al., 2014). Moreover, in some studies, no correlation was reported between MBL production and clinical characteristics of the admitted patients (Shirani et al., 2016; Zavascki et al., 2006). In this study, 53.2 % P. aeruginosa strains produced metallo-β-lactamase which was lower than reports from Iran, where 61.5 % metallo-β-lactamase producing P. aeruginosa strains were detected (Muddassir et al., 2021). Moreover, the prevalence of reduced numbers of MBL producers (40 %) was determined among carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa in Korea. The percentage of metallo-β-lactamase producing strains varied based on sampling size and region. The antibiotic, cephalosporin has been recommended to treat P. aeruginosa strains producing metallo-β-lactamases and in the present study, colistin and ceftazidime were effective against P. aeruginosa strains. Ismail and Mahmoud (Ismail and Mahmoud, 2018) detected three New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases (NDM-1 and NDM-2) producing strains from Iraq and in our study a total of five NDM-1 strains were detected.

In the present study, the biofilm was viewed under confocal microscopy and the combined effect of colistin and ceftazidime on biofilm was studied. The results revealed the antibiofilm and antimicrobial activity of antibiotics. Antibiotics reduced cell density and less dense microbial cells were observed. These findings revealed the antibiofilm potential of colistin and ceftazidime in vitro against biofilm-forming P. aeruginosa. It is reported that > 80 % of infections are associated with bacterial biofilm and P. aeruginosa is one of the major causative Gram-negative bacteria. Currently, only a few therapeutic options are available to treat biofilm pathogens. Doripenem and tobramycin have been effective in treating Gram-negative P. aeruginosa and prolonged use of aminoglycosides mediates biofilm formation (Bergen et al., 2008). Alanazi et al. (2023) analyzed the prevalence of drug-resistant bacteria from the Tertiary Hospital in Hail, Saudi Arabia. A recent retrospective analysis revealed the prevalence of drug-resistant uropathogens from pediatric patients in tertiary hospital at Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia (Alzahrani et al., 2021). Analysis of drug-resistant patterns of bacterial strains is useful to prescribe antibiotic use. Monitoring the use and dosage of antibiotics was useful to determine the cause of drug-resistance bacteria and to improve physician’s knowledge. In this study, colistin combined with ceftazidime was highly susceptible to P. aeruginosa. Colistin was considered an effective antibiotic to treat highly complex P. aeruginosa.

5 Conclusions

The study results revealed that the isolates were resistant to aminoglycosides. MCR-1 and blaNDM−1 genes were found in multidrug-resistant organisms. The bacteria obtained from the nasal swab, pus, and throat swab all had antibiotic resistance genes. Colistin and ceftazidime treatment prevented the production of early biofilms in MDR P. aeruginosa strains. These antibiotics had more synergistic efficacy and effectively inhibited early biofilm growth than individual antibiotics.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ayoub Al Othaim: Methodology, Investigation, Analysis. Saleh Aloyuni: Conceptualization. Ahmed Ismail: Conceptualization, Methodology, Analysis, Writing – original draft, Supervision. Alaguraj Veluchamy: Conceptualization, Validation. Bader Alshehri: Conceptualization, Validation. Ahmed Abdelhadi: Conceptualization, Validation. Rajendran Vijayakumar: Writing – review & editing. Palanisamy Manikandan: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation.

Acknowledgement

The author extends the appreciation to the Deanship of Postgraduate Studies and Scientific Research at Majmaah University for funding this research work through the project number R-2024-1247.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- In vitro antibacterial, antifungal, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer properties of isosteviol isolated from endangered medicinal plant Pittosporum tetraspermum. Evi-Based Complement Alt Med. Article ID 2015164261

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Detection of metallo-β-lactamases-encoding genes among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a tertiary care hospital, Kathmandu Nepal. BMC Res. Notes. 2017;10:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Infection prevalence at a tertiary hospital in hail, Saudi Arabia: a single-center study to identify strategies to improve antibiotic usage. Infect. Drug. Res. 2023:3719-3728.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retrospective analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility of uropathogens isolated from pediatric patients in tertiary hospital at Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia. In Healthcare. 2021;9(11):1564. (MDPI)

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil of four medicinal plants and protective properties in plum fruits against the spoilage bacteria and fungi. Ind. Crop. Prod.. 2019;133:54-62.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of once-, twice- and thrice-daily dosing of colistin on antibacterial effect and emergence of resistance: Studies with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2008;61:636-642.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biofilm and Quorum sensing mediated pathogenicity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Process Biochem.. 2020;96:49-57.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli other than Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. causing respiratory tract infections in a tertiary care center. J. Global Infect. Dis.. 2013;5(4):144.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metallo-β-lactamase-producing clinical isolates from patients of a tertiary care hospital. J. Lab. Phy.. 2011;3(02):093-097.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microtiter plate assay for assessment of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2002;68(6):2950-2958.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Detection of metallo-beta lactamases among carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Jundishapur J. Microbiol.. 2014;7:e12289.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of blaNDM-1 encoding imipenemase among the imipenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli isolated from various clinical samples at a tertiary care hospital of eastern Nepal: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Int. J. Microbiol.. 2020;1–5

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Infection of Mother and Baby. Keeling’s Fetal Neonatal Pathol.. 2022;1:207-245.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Detection of OXA-48 gene in carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from urine samples. Infect. Drug. Resis.. 2020;23:11-21.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of integrons and gene cassettes among metallo-β-lactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Infect. Epidemiol. Med.. 2017;3:36-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenotypic and genotypic diversity of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from bloodstream infections recovered in the hospitals of Belo Horizonte. Brazil. Chemotherapy.. 2014;60:54-62.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- First detection of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases variants (NDM-1, NDM-2) among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from Iraqi hospitals. Iranian J. Microbiol.. 2018;10(2):98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endemic carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with acquired metallo-beta-lactamase determinants in European hospital. Emerg. Infect. Dis.. 2004;10(3):535-538.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Taiwan: prevalence, risk factors, and impact on outcome of infections. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect.. 2016;49(1):52-59.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nosocomial infections with metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: molecular epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features and outcomes. J. Hosp. Infect.. 2014;87:234-240.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of carbapenem non-susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Eastern Algeria. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Cont.. 2015;4:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Determination of carbapenem resistance mechanism in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from burn patients, in Tehran. Iran. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health.. 2017;7:155-159.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Activities of carbapenem and comparator agents against contemporary US Pseudomonas aeruginosaisolates from the CAPITAL surveillance program. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.. 2013;75:412-416.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and high incidence of metallo-β-lactamase and AmpC-β-lactamases in nosocomial Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Iranian J. Basic. Med. Sci.. 2021;24(10):1373-1379.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of esbls in uro-pathogens obtained from a nigerian tertiary hospital. Niger. J. Pharm. Res.. 2021;16(S):139-147.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Overexpression of MexAB-OprM efflux pump in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch. Microbiol.. 2016;198:565-571.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of five common essential oil components on Listeria monocytogenes biofilms. Food. Microbiol.. 2008;19(11):1070-1075.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Resistance profile and biofilm production of Enterococcus spp., Staphylococcus sp., and Streptococcus spp. from dairy farms in southern Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol.. 2023;54(2):1217-1229.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular characterization of NDM-1-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from hospitalized patients in Iran. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob.. 2021;20:1-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance pattern and evaluation of metallo-beta lactamase genes (VIM and IMP) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains producing MBL enzyme, isolated from patients with secondary immunodeficiency. Adv. Biomed. Res.. 2016;5:124.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coexistence of virulence factors and efflux pump genes in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: analysis of biofilm-forming strains from Iran. Int. J. Microbiol.. 2021;2021(1):5557361.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for nosocomial infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing metallo-beta- lactamase in two tertiary-care teaching hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2006;58:882-885.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]