Translate this page into:

Metabolite profiling of Streptomyces sp. Al-Dhabi-100 isolated from the marine environment in Saudi Arabia with anti-bacterial, anti-tubercular and anti-oxidant potentials

⁎Corresponding author. naldhabi@ksu.edu.sa (Naif Abdullah Al-Dhabi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Recently, bioprospecting of marine actinomycetes has attracted because of the exploration of novel metabolites with promising biological applications such antibacterial, antimicobacterial antioxidant. Therefore, the present study has been aimed to explore the isolation and characterization promising marine actinomycetes from the Jazan region of Saudi Arabia and metabolite profiling of the extracellular metabolites together with assessment of anti-bacterial, anti-tubercular and anti-oxidant potentials. The extracellular metabolites were profiled using gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrum and MIC and MBC values of the fractions were evaluated by broth microdilution techniques. Biochemical, micromorphological and 16S rRNA gene analysis study clearly confirmed that the promising strain Al-Dbabi-100 belonged to the genus Streptomyces. MIC values of the fraction noted as 62.5 µg/ml for E. faecalis, 31.25 µg/ml for B. subtilis, 125 µg/ml for S. aureus, 250 µg/ml for S. epidermidis and 125 µg/ml for K. pneumoniae respectively and cell growth inhibition study resulted 19.78%,71.4% and 91.6% inhibition towards K. pneumoniae, E. coli and P. aeruginosa pathogens. Interestingly, the fraction revealed promising antitubercular and antioxidant activities. GCMS analysis showed 1-(2,6-Dimethyl-4-propoxyphenyl)propan-1-one (7%) and ethyl 2-propylphenyl ester (11.9%) as the major compounds.

Keywords

Marine actinomycetes

Antibacterial

Anti-tubercular

Antioxidant

1 Introduction

Mycobacterium includes obligate and opportunistic pathogens, some species tend to infect internal organs such as lungs while others invasive and infect skin, the major diseases caused by Mycobacterium species (Cook et al., 2009; Han and Silva, 2014). Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is Gram positive, aerobic, rod shaped and acid-fast bacteria are responsible for tuberculosis (TB) (Sakamoto, 2012). Tuberculosis is one of the oldest recorded disease and most devastating infectious diseases (Smith, 2003; Forrellad et al., 2013). According to the statistics of world health organization (WHO), nearly 10 millions are infected annually. Approximately 1.2–1.4 million people die each year owing to the infection by Mtb (WHO, 2012, 2018). Tuberculosis infection can be controlled through chemotherapy treatment by the of combinations of number of antibiotics, first-line anti-TB drugs includes, isoniazid and rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol while in the second-line anti-TB drugs, ethionamide, fluoroquinolones, streptomycin, amikacin and kanamycin can be used (Laurenzo and Mousa, 2011). Nevertheless, the resistance strains lead to hinder the success of TB control programs. Drug-resistant tuberculosis has become a major concern for public health in all over the world (Zaman, 2010; US Centers for Disease Control, 2010). World Health Organization in 2018 report estimated that 18% of treated cases and 3.5% of new cases have multidrug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis (MDR-TB) (WHO, 2018). The hinders the rising of resistant M. tuberculosis strains, there is an urgent need to discover a novel anti-mycobacterial agent with a unique mechanism of action for infection caused by MDR-TB strains (Table 1).

R.T

Compound Name

Area

Area%

6.2012

Benzenebutanoic acid

269,244,150

2.82

6.9212

Acetophenone, 3′-fluoro-4′-methoxy-

16,083,866

0.17

7.7587

Carbamic acid, N-[1,1-

11,049,988

0.12

8.2608

Carbamic acid, N-[1,1-

114,754,694

1.20

8.6179

Benzestrol

423,523,630

4.44

8.7092

Carbamic acid, N-[1,1-

881,109,432

9.24

8.788

1-(2,6-Dimethyl-4-propoxyphenyl)propan-1-one

1,242,330,187

13.03

8.8549

Phenol, 4-(1,1-dimethylpropyl)-

1,016,472,442

10.66

8.9092

1-(2,6-Dimethyl-4-propoxyphenyl)propan-1-one

676,704,799

7.10

9.0007

Benzestrol

524,022,596

5.50

9.0485

4′-Propoxy-2-methylpropiophenone

339,346,271

3.56

9.0964

Phthalic acid, ethyl 2-propylphenyl ester

1,137,483,680

11.93

9.179

Carbamic acid, N-[1,1-

926,047,736

9.72

bis(trifluoromethyl)ethyl]-, 4-(1,1,3,3-

0.00

tetramethylbutyl)phenyl ester

0.00

9.2247

1-(2,6-Dimethyl-4-propoxyphenyl)propan-1-one

394,495,917

4.14

9.2747

Phenol, 2-methyl-4-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylbutyl)-

496,647,093

5.21

9.4726

Carbamic acid, N-[1,1-

47,750,200

0.50

9.5401

1,3,5-Trimethyladamantane

28,342,781

0.30

9.6031

Carbamic acid, N-[1,1-

88,537,914

0.93

9.6618

Carbamic acid, N-[1,1-

26,652,755

0.28

0.00

tetramethylbutyl)phenyl ester

0.00

9.7228

Phenol, 2-methyl-4-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylbutyl)-

34,895,159

0.37

9.7641

Carbamic acid, N-[1,1-

21,336,541

0.22

9.9903

Benzestrol

22,959,728

0.24

10.1469

Hexestrol, O-trifluoroacetyl-

8,775,841

0.09

10.2426

Caffeine

52,542,268

0.55

10.3579

1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-

32,920,637

0.35

methylpropyl) ester

0.00

10.9147

Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester

115,516,821

1.21

11.4999

Dibutyl phthalate

88,586,431

0.93

12.1176

Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-

144,290,842

1.51

dimethylethyl)-4-hydroxy-, ethyl ester

0.00

12.8985

Desogestrel

14,595,261

0.15

13.1378

1-Naphthalenepropanol, .alpha.-

20,335,994

0.21

13.4444

8,11-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester

26,815,518

0.28

13.5358

9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, (E)-

80,734,655

0.85

13.9491

Methyl stearate

85,798,239

0.90

14.5212

Androst-5,16-diene-3.beta.-ol

14,632,206

0.15

14.6343

Octadecanoic acid, 10-methyl-, methyl ester

32,043,034

0.34

16.7746

.psi.,.psi.-Carotene, 3,3′,4,4′-tetradehydro-1′,2′-

12,180,409

0.13

dihydro-1-hydroxy-1′-methoxy-

0.00

19.4565

Corticosterone

23,998,547

0.25

20.296

.beta.-Carotene-3,3′-diol, (3R,3′R)-all-trans-

13,968,889

0.15

21.2706

17Alpha-ethynyl-6beta-methoxy-3alpha,5-

10,234,417

0.11

cyclo-5alpha-androstane-17beta,19-diol

0.00

21.6318

Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

13,892,588

0.15

Total

9531654156.00

100.00

Actinobacteria, mainly species of the genus Streptomyces are prolific source for producing antibiotics and other bioactive secondary metabolites, approximately half of the usable antibiotics are produced by actinobacterial genera (Berdy, 2005; Al-Dhabi et al., 2016; Al-Dhabi et al., 2018a). Several compounds have been derived from Streptomyces with anti-mycobacterials activity such as Caprazamycin B (Igarashi et al., 2003), Sansanmycins (Xie et al., 2007), Urdamycinone E, Urdamycinone G and Dehydroxyaquayamycin, Streptcytosine A (Bu et al., 2014), Chrysomycin A (Arasu et al., 2013; Arasu et al., 2019) and Dinactin (Hussain et al., 2018; Valsalam et al., 2019). We hypothesized that unexplored and extreme environments may harbor Streptomyces species that can produce unique bioactive molecules with novel antibacterial properties against M.tuberculosis. Therefore, the current study was aimed to isolate Streptomyces Al-Dhabi-100 from the marine region of Saudi Arabia and determine its antibacterial, antimycobacterial and antioxidant activities against clinical M. tuberculosis strains.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and reagents

Antibiotics such as streptomycin, actidione and nalidixcic acid was purchased from Himedia, India. Components used for the microbiological media preparations were obtained from Sigma. Different organic solvents such as hexane, ethyl acetate, chloroform and methanol were procured from Somatco, Saudi Arabia. The distilled water used for the experiments were RO treated and sterilized.

2.2 Pathogenic strains and its cultivation

For antimicrobial study different pathogenic strains such as E. faecalis, B. subtilis, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa were gifted from the College of medicine King Saud University medical hospital. The pathogenic strains were stored as the lyophilized form and the strains were activated by thawing down and transferred into the sterile 20 ml nutrient broth containing flask with additional 10% tryptone and incubated under shaking condition for 24 h at 37 °C. After occurrence of growth in the form of cell suspension, the cells were streaked on the nutrient agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The purity of the pathogenic strains were evaluated and further stored in the refrigerator for the routine lab work and cell suspensions were mixed with 20% sterile glycerol and stored in the deep freezer for the prolonged uses.

2.3 Isolation of marine actinomycetes for antimicrobial activities

For the isolation of marine actinomycetes, marine sediment, marine soil samples, marine water, marine rock powder, marine fishes and marine decayed plants were collected from the different locations of ocean areas in Jazan region, Saudi Arabia. Soon after collecting the samples using sterile spatula, the samples were transferred into the sterile storage container and kept in the ice box till reaching the laboratory (Al-Dhabi et al., 2019a).

2.4 Determination of antimicrobial activity of the actinomycetes

Antimicrobial activities of the actinomycetes were determined by cross streak perpendicular method. Briefly, the spore suspension of the actinomycetes were prepared using 0.9% ice cold saline water and streaked on the center of the MNG agar medium and kept at 30 °C for 14 days. After incubation, the freshly cultivated different pathogenic bacteria were streaked perpendicular to the actinomycetes and determined for its inhibition property my measuring the zone of inhibition. Once isolates with promising antimicrobial activity was selected and studied further by characterization using biochemical, 16S rRNA identification and mass cultivation and chemical compound extraction.

2.5 Mass cultivation of marine actinomycetes and organic solvent extraction

Mass cultivation of the marine actinomycetes was performed for the bulk level extraction of crude compounds. Briefly, MNG broth supplemented with 40% marine water and 10% glucose was used as the base for the fermentation medium. About 1000 ml of the fermentation broths were transferred into 2000 ml Erlen Mayer flask, after adjusting the pH to 7.0. the flasks were sterilized. Separately, the spore suspensions of the active marine actinomycetes were prepared using 0.9% saline water and 10 percentage of the spore suspensions were transferred into the flask as the starting inoculums. After that the flasks were incubated at 30 °C for 25 days. The excretion of the antimicrobial substances was visually identified by changing the color from yellow to dark black. After incubation, the cells were separated by centrifugation at 10,000 RPM for 15 min. The collected supernatant was tested for antimicrobial activity by cup plate diffusion method to ensure the antimicrobial property of the supernatant. Further, the supernatant was mixed with 1:3 ratio of ethyl acetate. The crude antimicrobial components were concentrated using the vacuum evaporator with the operating conditions at 35 °C at low pressure. The concentrated substances also checked for its antimicrobial activity by disc diffusion method. Further, silica gel column was packed using 45 cm length and 5 cm width glass column. The crude extracts were eluted using different proportion of the organic solvents such as hexane, ethyl acetate and methanol. The collected six fractions were checked for its purity using thin layer chromatography and the spots with similar rf values were pooled together and evaluated for their antimicrobial activity by disc diffusion method. One fraction with better antimicrobial activity against the tested bacterial pathogens was further tested for MIC values, Anti-tubercular activity, antioxidant activities and chemical characterization.

2.6 MIC and MBC values of the fraction

Antibacterial activity of the fraction was accessed by broth micro dilution method (Arasu et al., 2017).

2.7 Cell wall disruption study

The cell wall disruption study of the fraction was tested by transferring 50 µg/ml concentration (Al-Dhabi et al., 2018).

2.8 Anti-tubercular activity of the fraction

Luciferase Reporter Phage (LRP) assays was followed for the determination of the antituberculosis property of the fraction with slight modifications from the method of Sivakumar et al. (2007). Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv strain was cultivated in Middlebrook G7H9 broth with the concentration of #2 MacFarland standards. Briefly, 100 µg/mL of the fraction and 100 µL of freshly prepared M. tuberculosis cell containing 1 ml sterile cryovial were mixed with 300 µL of the G7H9 containing sterile freshly prepared 10% albumin dextrose complex and 0.5% glycerol and incubated at 37 °C for 3 days in an incubator. Separately only sterile water was used as the control. After the proper incubation, approximately 50 μL solution (25 μL of 0.1 M CaCl2 and 25 μL of titre mycobacteriophage phAETRC202) was carefully transferred into the vial and mixed thoroughly and kept in an incubator at 37 °C for 3 days. After the incubation, 100 μL of the mixed samples were transferred into a specialized luminometer cuvette containing 100 μL of D-luciferin. After the addition of D-luciferin, relative light unit (RLU) was noted in a luminometer (Model – Monolight 2010). The reduction in the RLU value was calculated by following the equation

The RLU values with less than 50% were considered as the promising anti-tubercular activities.

2.9 Antioxidant activities of the fraction

2.9.1 DPPH radical scavenging assay

DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) free radical scavenging assay was by following the methodology of Valsalam et al. (2019) with slight changes. The transformation of the color changes was recorded and the antioxidant potentials were calculated using the below mentioned formula.

2.9.2 Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

Fenton reaction method with slight modification was followed for the measurement of hydroxyl radical scavenging assay (He et al., 2004).

2.9.3 Nitric oxide scavenging activity

Modified version of Dharmendra Singh et al. (2012) was followed for the determination of the nitric oxide scavenging properties of the fractions.

2.10 Chemical profiling of the fraction by GC–MS

The individual chemical composition of the fraction was assessed by subjecting the fraction to the gas chromatography. Briefly, the methodology for operating the gas chromatography instrument was followed from our previous publications. The chemical components were compared with the library of the mass spectrum and the percentage of the individual components was calculated.

3 Results

3.1 Isolation and screening of actinomycetes for antimicrobial potential

In the present study strains with different morphological features were isolated from the coastal region of Jazan and screened for the antimicrobial activity. Among the collected stains, the stain Al-Dhabi-100, pronounced significant antimicrobial activities were selected for further characterization and chemical profiling. The biochemical studies confirmed that the strain was Gram positive, spore forming and aerobic in its properties. Also, the strain was able to produce extra cellular enzymes such amylase, protease and cellulase respectively. Growth characteristics of the strain was performed in different cultivation medium suggested that the strain was filamentous in the initial m stage of the growth and able to bear spore generate spores in its outer surfaces. In addition, the strain cannot able to produce diffusible pigment in the medium. The antimicrobial senility and resistance pattern of the strain towards various studies antibiotics were attractive. Especially the strain was resistance to streptomycin confirmed that the strain belonged to the genus Streptomyces. The 16S rRNA gene sequence obtained from the strain showed 99% percentage similarity and identity towards the Streptomyces strains deposited in the gene bank.

3.2 Antibacterial activity of the fraction

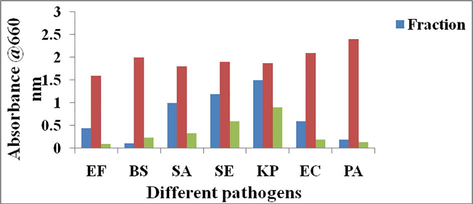

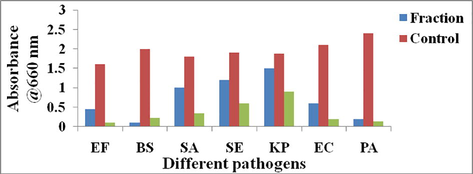

MIC and MBC values of the fractions were shown in figure. The results indicated that the fraction showed MIC values of 62.5 µg/ml for E. faecalis, 31.25 µg/ml for B. subtilis, 125 µg/ml for S. aureus, 250 µg/ml for S. epidermidis and 125 µg/ml for K. pneumoniae respectively (Fig. 1). The MBC values were ranged from 62.5 µg/ml to 500 µg/ml respectively for the studied microbial pathogens. The strand antibiotics streptomycin showed 25 µg/ml to 50 µg/ml respectively for the studied microbial pathogens.

MIC and MBC values of the fraction obtained from the Streptomyces sp strain Al-Dhabi-100.

3.3 Cell growth inhibition assay

The cell growth inhibition properties of the fractions towards the microbial pathogens were displayed in Fig. 2. The results indicated that E. faecalis, B. subtilis, S. aureus and S. epidermidis 72%,94%,44% and 37% cell killing compared to the control whereas K. pneumoniae, E. coli and P. aeruginosa documented 19.78%, 71.4% and 91.6% respectively. The standard antibiotic suppressed above 95% of the cell growth in the suspension conditions.

Cell suspension inhibition assay of the fraction obtained from the Streptomyces sp strain Al-Dhabi-100.

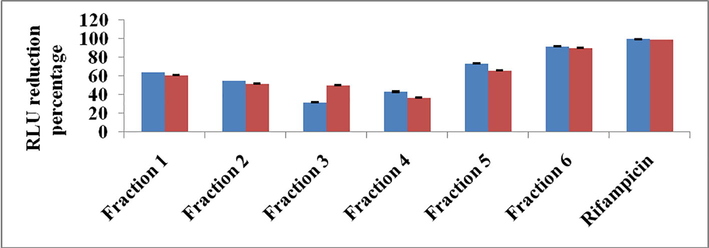

3.4 Anti-tubercular activity of the fraction

The six fractions obtained from the active ethyl acetate extracts were tested for the antimicobacterial studies against the virulent strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Results indicated that the six extracts comparatively showed antimicobacterial activities (Fig. 3). Among the fractions, fraction 6 effectively inhibited the growth of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv. The percentage of the RLU reduction was noted in the figure. It is revealed that fraction 6 showed 91.5% of reduction and the other fractions were lesser than the fraction 6. Also the standard antibiotic rifampicin showed 99.6% at 100 µg/ml level.

Antimicobacterial activity of the fraction obtained from the Streptomyces sp strain Al-Dhabi-100 Blue color; 100 µg/ml concentration, red color 50 µg/ml concentration.

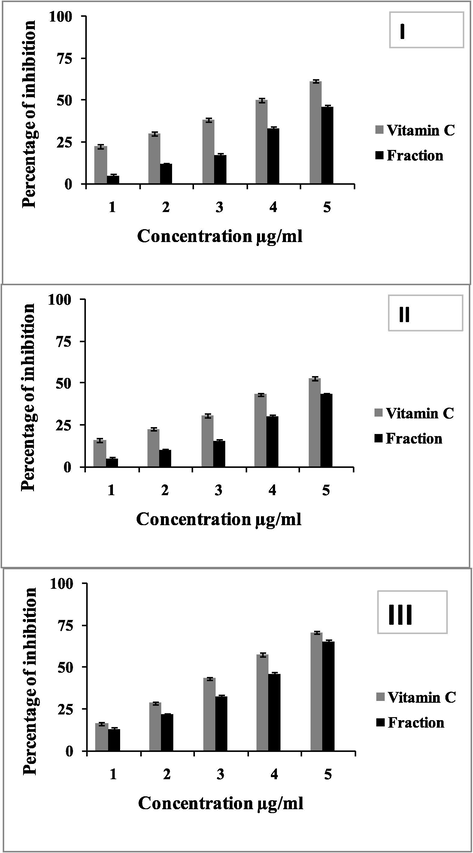

3.5 Antioxidant activities of the fraction

The antioxidant potentials of the fractions were showed in the Fig. 4. DPPH activity study of the fraction revealed that the antioxidant activities were concentration specific. The fifty percentage antioxidant potentials were noted at 5 µg level fraction. Whereas, the concentration from 1, 2, 3 and 5 µg showed 5 and 11.6, 17.33 and 33% percentage respectively. Similarly hydroxyl radical scavenging activity and nitric oxide scavenging activity of the fraction also documented as concentration specific. The antioxidant potentials were directly proportional to the concentration of the fractions. Even though the standard vitamin showed better antioxidant activity, the fractions were slightly lesser in its antioxidant potentials.

Antioxidant properties of the fraction obtained from the Streptomyces sp strain Al-Dhabi-100. I; DPPH, II, hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, III; nitric oxide scavenging activity.

3.6 Chemical profiling of the fraction

Chemical profiling of the fraction guided the presence of various compounds such as benzenebutanoic acid (2.8%), benzestrol (4.44%), 1-(2,6-Dimethyl-4-propoxyphenyl)propan-1-one (13%), phenol, 4-(1,1-dimethylpropyl)- (10.66%), 1-(2,6-Dimethyl-4-propoxyphenyl)propan-1-one (7.0%), ethyl 2-propylphenyl ester (11.9%), Phenol, 2-methyl-4-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylbutyl)- (5.2%), Androst-5,16-diene-3.beta.-ol (0.1%) and .beta.-Carotene-3,3′-diol, (3R,3′R)-all-trans- (0.1%) respectively.

4 Discussion

In general, the extracellular secondary metabolites released from different micro organisms were used as an antibiotics, pigments, toxins, signal blocking agents and enzyme inhibitors (Misra and Fridovich 1972; Tortoli, 2006; Arokiyaraj et al., 2015; Magdy et al., 2017; Al-Dhabi et al., 2018b, 2019a). Among the secondary metabolites, 71% (15,000 numbers) of the total identified compounds were isolated and identified from the marine origin microorganism (Ahmad and Fatma, 2017; Al-Dhabi et al., 2019d). Because of the variations in the marine environments such as different temperature, alternations in the marine environmental pressures, different dissolved oxygen concentrations, different salt concentrations and the availability of the nutrients to the microorganisms stimulate the synthesis and production of structurally variable secondary metabolites with the presence of wide level functional groups (Blunt et al., 2017; Al-Dhabi et al., 2019b). Interestingly, above 91% of the marine natural products were characterized from the marine actinomycetes. Especially, the secondary metabolites obtained from the marine actinomycetes revealed wide level activities as antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer, antidiabetic, antiinflammatory, antianalgesic and cytotoxic characters (Balachandran et al., 2015; Al-Dhabi et al., 2019c). Considering the important properties of marine actinomycetes, the present study has been initiated for the isolation and characterization of novel marine Streptomyces from the Jazan region of Saudi Arabia and determined the chemical profiling and antibacterial, antimicobaterial and antioxidant properties of the isolated active strain. The promising strain Al-Dhabi-100 was different from the other isolated strains with regards to the morphological characteristics and biochemical properties. 16S rRNA gene analysis results confirmed that the stains were closely related to the genus Streptomyces. Also, it is predicted that marine region of Jazan is an ideal place for the cultivation of novel actinomcyetes with promising antibacterial and antifungal properties. Similarly, different actinomcyetes such as Nocardioides, Blastococcus, Serinicoccus, Clavibacter, Nocardiopsis, Actinomadura, Kytococcus, Nesterenkonia, Knoellia and Salinibacterium were identified from the coastal region of Chilie with different biological properties (Undabarrena et al., 2016).

The novel strain Al-Dhabi-100 exhibited antibacterial activity in both solid and liquid fermentation medium clearly evidenced that the produced extracellular metabolites were active in both solid and liquid level. Therefore, efforts were made to extract the active compounds using ethyl acetate and further the column purification technique guided to the collection of six fractions. The fraction 6 comparatively showed good antibacterial activities against the Gram positive and Gram negative clinical pathogens. The outer cell surface of the Gram negative bacteria protects the cells by acting as a barrier to stop the protrusion of the antibiotics or other toxic compounds, however, it is proved that the fraction obtained from the strain Al-Dhabi-100 effectively break the barriers of the cells and might be entered into the cells thereby alter or block the cellular constituents, thereby, the growth of the microbial pathogens was limited (Miller, 2016).

Ashforth et al. (2010) claimed that the structurally variable secondary metabolites derived from marine actinomycetes were known for the treatment of tuberculosis. Antibiotics such as actinomycin, streptomycin, and caprazamycin from different antinomycetes such as Streptomyces antibioticus and Actinomadura sp exhibited better antimicobacterial activities (Ashforth et al., 2010). In coincidence with the previous report, the present study, the fractions obtained from the ethyl acetate extract also revealed above 90% inhibition of the tuberculosis causing strains confirmed the fractions activities.

The antioxidant properties of the fraction were an additional advantage of the strain Al-Dhabi-100. Antioxidants play a vital role in scavenging the free radicals and protecting the human cells from various oxidative stresses. The secondary metabolites containing the phenolic compounds as the functional group in its chemical structure generally exhibited antioxidant properties and thereby showing promising activities such as anti-inflammatory, vascular activity, antitumour activity (Shimamura et al., 2007). Inconsistent with the reports, the identified fraction showed antioxidant activities closely similar to the synthetic vitamin c compounds. With regards to the antioxidant properties, the novel molecules present in the fractions have the chance to use as a chemotherapeutic agent in the pharmaceutical industry.

5 Conclusion

In the present study, novel Streptomyces strain Al-Dhabi-100 isolated from the marine region of Jazan showed good antibacterial activities against the studied pathogens. The MIC and MBC values of the fraction were ranged from 31.25 to 500 μg/mL for the gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. Besides that, the fraction exhibited significant cell suspension inhibition activity against E. faecalis (72%), B. subtilis (94%), S. aureus (44%) and S. epidermidis (37%). Antimicobaterial activity of the fraction towards M. tuberculosis H37Rv was its additional advantage. The antioxidant potential of the fraction would be useful in reducing the stress-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by the National Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation (MAARIFAH), King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Award Number (12-BIO2920-02).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Production of indole-3-acetic acid by cyanobacterial strains. Nat. Prod. J.. 2017;7:112-120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, identification and screening of antimicrobial thermophilic Streptomyces sp. Al-Dhabi-1 isolated from Tharban hot spring, Saudi Arabia. Extremophiles. 2016;20:79-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical profiling of Streptomyces sp. Al-Dhabi-2 recovered from an extreme environment in Saudi Arabia as a novel drug source for medical and industrial applications. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2019;26:758-766.

- [Google Scholar]

- Environmental friendly synthesis of silver nanomaterials from the promising Streptomyces parvus strain Al-Dhabi-91 recovered from the Saudi Arabian marine regions for antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2018;189:176-184.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles produced from marine Streptomyces sp. Al-Dhabi-89 and their potential applications against wound infection and drug resistant clinical pathogens. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 2019111529

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of silver nanomaterials derived from marine Streptomyces sp. Al-Dhabi-87 and its in vitro application against multidrug resistant and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase. Clin. Pathog. Nanomater.. 2018;8(5)

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactivity assessment of the Saudi Arabian Marine Streptomyces sp. Al-Dhabi-90, metabolic profiling and its in vitro inhibitory property against multidrug resistant and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase clinical bacterial pathogens. J. Infect. Public Health. 2019;12:549-556.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents of Streptomyces sp. strain Al-Dhabi-97 isolated from the marine region of Saudi Arabia with antibacterial and anticancer properties. J. Infect. Public Health 2019

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green chemical approach towards the synthesis of CeO2 doped with seashell and its bacterial applications intermediated with fruit extracts. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2017;172:50-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- One step green synthesis of larvicidal, and azo dye degrading antibacterial nanoparticles by response surface methodology. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2019;190:154-162.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial and antifungal activities of polyketide metabolite from marine Streptomyces sp. AP-123 and its cytotoxic effect. Chemosphere. 2013;90(2):479-487.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of Silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Taraxacum officinale and its antimicrobial activity. South Indian J. Biol. Sci.. 2015;2:115-118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioprospecting for antituberculosis leads from microbial metabolites”. Nat. Prod. Rep.. 2010;27:1709-1719.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of Streptomyces sp. (ERINLG-51) isolated from Southern Western Ghats. South Indian J. Biol. Sci.. 2015;1:7-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-mycobacterial nucleoside antibiotics from a marine-derived Streptomyces sp. TPU1236A. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:6102-6112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adv. Microb. Physiol.. 2009;55(81–182):318-319.

- Virulence factors of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Virulence. 2013;4:3-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photometric determination of hydroxyl free radical in Fenton system by brilliant green. Am. J. Clin. Med.. 2004;6:236-237.

- [Google Scholar]

- Streptomyces puniceus strain AS13. Production, characterization and evaluation of bioactive metabolites: a new face of dinactin as an antitumor antibiotic. Microbiol. Res.. 2018;207:196-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caprazamycin B, a novel anti-tuberculosis antibiotic, from Streptomyces sp. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 2003;56:580-583.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and current status of rapid molecular diagnostic testing. Acta Trop.. 2011;119:5-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nigragillin, Nigerazine B and five Naphtho–pyrones from Aspergillus japonicus isolated from hot desert soil. Nat. Prod. J.. 2017;7:216-223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance and regulation of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane barrier by host innate immune molecules. MBio. 2016;7:e01541-e1616.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem.. 1972;247:3170-3175.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pathology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Vet. Pathol.. 2012;49:423-439.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of action and potential for use of tea catechin as an anti-infective agent. AntiInfect. Agents Med. Chem.. 2007;6:57-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and molecular determinants of virulence. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.. 2003;16:463-496.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the diversity and antimicrobial potential of marine actinobacteria from the comau fjord in Northern Patagonia, Chile. Front. Microbiol.. 2016;7:1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR TB) Fact Sheet. Atlanta: United States Centers for Disease Control; 2010.

- Rapid biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from the leaf extract of Tropaeolum majus L. and its enhanced in-vitro antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant and anticancer properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2019;191:65-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2018. Global tuberculosis report 2018.

- World Health Organization, 2012. Global Tuberculosis Report 2012.

- Tuberculosis: a global health problem. J. Health Popul. Nutr.. 2010;28:111-113.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]