Translate this page into:

Larvicidal potential of Thuja orientalis leaves and fruits extracts against Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Botanical pesticides targeted to avoid the pesticide resistance to synthetic ones that conventionally affecting ecosystems diversity. The study designed to evaluate the larvicidal potentials of leaves and fruits extracts (methanol, acetone, hexane, and aqueous) from Thuja orientalis (Pinales: Cupressaceae) against Culex pipiens 3rd instar larvae and to identify the extracts compounds by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) method of analysis. Leaves and fruits extracts used in concentrations, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 ppm against the 3rd larval instar of Cx. pipiens in five replicates and larval mortalities recorded after 24 and 48 h post exposure. The larvicidal potentials of extracts showed concentration dependent and varied between leaves and fruits extracts. At 400 ppm concentration, leaves extracts showed 100 % larval mortality except in hexane extract exhibited 98 %. Acetone, methanol, aqueous and hexane leaves extracts recorded LC50 values, 58.04, 70.20, 77.19 and 84.25 ppm, respectively. Fruits extracts by hexane and methanol exhibited 100 % larval mortality and LC50, 68.26 and 83.21 ppm, respectively, while, acetone and aqueous fruits extracts showed 98 % and 96 % larval mortality and LC50, 92.81 and 102.97 ppm, respectively. Terpenoids and sesquiterpenoids, fatty acid esters mainly identified in both extracts.

The present study showed that extracts from Thuja orientalis leaves and fruits acquired promising larvicidal potential for the control of Cx. pipiens larvae with the role of their chemical constituents.

Keywords

Thuja orientalis

Methanol

Acetone

Hexane

Aqueous

Culex pipiens

Larvicidal

GC–MS

1 Introduction

Mosquitoes considered as a burden to human health by transmitting diseases including malaria, filariasis, dengue, and leishmaniasis (Wilson et al., 2020). Culex pipiens mosquitoes is common house mosquito and one of the most widely distributed mosquitoes worldwide due to its adaptation to human environments and its mode of feeding on birds and mammals reflected by its role in transmission of the West Nile virus and other pathogens (Farajollahi et al., 2011) that urged researches of its control.

Vector control is the main way to reduce public concerns about mosquito-borne diseases including filariasis, dengue, malaria, and leishmaniasis (Wilson et al., 2020). Control of mosquito larvae in aquatic phases is an effective method for reducing mosquito-spread (WHO, 2013). Excessive use of synthetic insecticides, with a complete lack of awareness of the strategy of changing the pesticides, led to resistance to pesticides along with environmental pollution and health risks to humans and non-target biota. Therefore, the search for environmentally friendly alternatives as plants or oils rich in secondary metabolites is a recent trend since they are more efficient, less toxic, biodegradable, and capable of insect decrease plant resistance to these natural compounds (Mouden et al., 2017; Ahmed et al., 2021) besides serving as larvicides, adult pesticides, insect repellents and deterrents (Govindarajan et al., 2016) they destroy only the insects they are meant to kill, leaving no residue on food or in the environment.

Thuja orientalis is a dense, evergreen and coniferous tree belongs to the family Cupressaceae growing in Saudi Arabia (Elsharkawy et al., 2017; Elsharkawy and Ali, 2019). In folk medicine T. orientalis used as herbal medicine for treatment of psoriasis, amenorrhea, enuresis, rheumatism, cystitis, bronchial catarrh and uterine carcinomas (Srivastava et al., 2012). Studies evaluated different activities of T. orientalis like, antimicrobial (Choi et al., 2021), antifungal activity (Caruntu et al., 2020), antioxidant (Nizam and Mushfiq, 2007), anticancer (Elsharkawy et al., 2017), anti-inflammatory (Darwish et al., 2021; Shin et al., 2015), hair growth promotion (Zhang et al., 2013).

The present study designed to investigate the larvicidal activities of methanol, hexane and acetone and aqueous extracts from leaves and fruits of Thuja orientalis plant against Cx. pipiens third instar larvae after exposure to extracts for 24 and 48 h. As well, identification of the chemical composition of the tested extracts by the aid of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) method of analysis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plants materials

Thuja orientalis L. (Pinales: Cupressaceae) leaves and fruits were obtained from Arar region, at Northern Region of Saudi Arabia, where growing wild in March 2022 as previously recorded (Elsharkawy and Ali, 2019). The plant was identified by a taxonomist, prof. Dr. Yahya Masrahi, from the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia.

2.2 Culex pipiens colony

Mosquitoes (Cx. pipiens) were obtained from the Center for Environmental Research and Studies at Jazan University. Rearing was performed under controlled conditions (27 ± 2 °C, relative humidity at 70 % ± 10 %, and 12:12 h light:dark regime). Mosquito larvae were reared in round enamel plates (25 × 20 × 10 cm) filled with 2 L de-chlorinated water and fed with fish food daily. The third instar Cx. pipiens larvae were used for the larvicidal examination.

2.3 Plant extracts.

Leaves and fruits were dried in shade for 7 days at laboratory temperatures (27–29 °C). The dried leaves (40 g) and fruits (25 g) were powdered using a commercial electrical stainless-steel blender and extracted for each solvent including methanol, acetone, hexane, and aqueous using Soxhlet apparatus for 6–8 h according to the solvent type. The leaves and fruits extracts were filtered with Whatman number 1 filter paper through a Buchner funnel. The filtrates then dried using a rotary evaporator under vacuum at 40 °C. The plant leaves extract yields 3.7, 3.2, 2.8, and 1.7 g for methanol, acetone, hexane, and aqueous solvents and yields 2.1, 1.5, 2.3 and 1.1 g for plant fruits, respectively.

2.4 Larvicidal assay

The larvicidal activity was determined for the extracts in concentrations that prepared as 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 ppm based on 1 g/1L (1000 ppm) from each extract stock solution against the 3rd larval instar of Cx. pipiens (WHO, 2005). Twenty Cx. pipiens third instar larvae of were subjected to each extract concentration in 250 mL glass beakers containing 150 mL de-chlorinated water (aqueous suspension) at 27 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 10 % RH, and a 12:12 h (L/D) photoperiod. Five replicates per concentration per extract and control were conducted. Larval mortalities were recorded after 24 and 48 h of exposure.

2.5 Identification of chemical compounds in extracts by gas chromatography-mass spectrometer.

Extracts from promising plant, Thuja orientalis L. were analyzed to investigate their chemical constituents by GC–MS using the Trace GC-TSQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) through TG–5MS direct capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 m thickness of the film) where the column oven temperature initially maintained at 50 °C, then rate was increased 5 °C/min up to 250 °C, for 2 min, and then increased 30 °C/min to 300 °C. The lines for the injector and MS transfer were suspended at 280 °C and 260 °C, respectively, helium was the carrier gas at the rate of 1 mL/min. The solvent delay was 3 min and 2 µl samples were injected automatically using Autosampler AS1310 coupled with GC in the splitless mode. In full scanning mode, electrospray ionization (EI) mass spectra were obtained covering the range 50–650 m/s at an ionization voltage of 70 V. The ion source temperature was fixed at 200 °C. The chemical constituents were identified from the Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC), where the chemical compounds were identified by comparison of their retention times and mass spectra with those of WILEY 09 and NIST 11 mass spectral databases.

2.6 Data analysis

The percentage mortalities were determined according to Abbott, (1925). The larval control results did not need correction, as the mortality was less than 5 %, according to the WHO guidelines (WHO, 2005) (no larval control mortality recorded throughout the study). Mortality data from all the replicates were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to find the differences among the activity between each plant extract concentrations using the least significant difference (LSD) test. Also, data from all the replicates were subjected to analysis to determine the larval LC50, LC90, and LC95 as well as chi-square values within confidence limits at 95 % (lower confidence limit (LCL) and upper confidence limit (UCL) by using probit analysis and regression between log extract concentration and probit values. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics v22 – 64 bit), and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3 Results

3.1 Larvicidal activity

The data about the larvicidal activities of the tested Thuja orientalis leaves extracts against the third instar larvae of Cx. pipiens after 24 h are summarized in Table 1, and after 48 h are summarized in Table 2. The analysis of responses of the leaves extracts revealed that the larvicidal activities after 24 h showed 100 % mortalities at 400 ppm of methanol, acetone and aqueous extracts. While hexane leaves extract at 400 ppm showed 98 % larval mortality. Acetone leaves extract showed the highest efficacy by inducing 100 % mortality (LC50, 58.04, LC90, 169.27, and LC95, 229.27 ppm), followed by methanol extract by 100 % mortality (LC50, 70.20, LC90, 221.66, and LC95, 307.07 ppm), followed by aqueous extract by 100 % mortality (LC50, 77.19, LC90, 244.26, and LC95, 338.95 ppm). While, hexane extract showed the least efficacy as compared to others, inducing 98.00 % mortality (LC50, 84.25, LC90, 283.47, and LC95, 399.84 ppm) (Table 1). The larvicidal activities of the leaves extracts after 48 h showed 100 % mortalities at 400 ppm for all tested extracts. Acetone leaves extract showed the highest efficacy (LC50, 43.40, LC90, 102.62, and LC95, 130.98 ppm), followed by methanol extract (LC50, 54.75, LC90, 156.00, and LC95, 209.92 ppm), followed by the aqueous extract (LC50, 63.76, LC90, 198.50, and LC95, 273.89 ppm). Then, hexane showed (LC50, 69.02, LC90, 225.14, and LC95, 314.78 ppm) (Table 2). Significance at 0.05 level between different superscripts. (a) In Chi-Square Tests, no heterogeneity factor was used in the calculation of confidence limits because the significance level was greater than 0.05. Significance at 0.05 level between different superscripts. (a) In Chi-Square Tests, no heterogeneity factor was used in the calculation of confidence limits because the significance level was greater than 0.05.

Leaves extract

Conc. ppm

Mortality%

(Mean ± SE)LC50

(LCL–UCL.)LC90

(LCL–UCL.)LC95

(LCL–UCL.)Chi

(Sig)Regression equation

R2

Methanol

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

70.20

(61.92–79.19)221.66

(185.53–278.05)307.07

(248.31–404.83)4.417

(0.220a)Y = −4.33 + 2.33*x

0.997

25

15.00 ± 2.24b

50

35.00 ± 3.16c

100

61.00 ± 4.30d

200

86.00 ± 2.45e

400

100.00 ± 0.00f

Acetone

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

58.04

(51.25–65.24)169.27

(143.49–208.94)229.27

(188.22–296.63)1.884

(0.597a)Y = −4.68 + 2.65*x

0.997

25

18.00 ± 2.55b

50

41.00 ± 2.92c

100

72.00 ± 2.55d

200

93.00 ± 2.55e

400

100.00 ± 0.00f

Hexane

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

84.25

(74.21–95.43)283.47

(234.18–361.87)399.84

(318.35–537.98)3.348

(0.341a)Y = −4.95 + 2.6*x

0.976

25

12.00 ± 2.00b

50

29.00 ± 3.32c

100

54.00 ± 2.45d

200

79.00 ± 2.45e

400

98.00 ± 1.22f

Aqueous

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

77.19

(68.22–87.06)244.26

(204.00–307.18)338.95

(273.22–447.30)5.630

(0.131a)Y = −4.32 + 2.27*x

0.999

25

13.00 ± 2.00b

50

31.00 ± 4.00c

100

58.00 ± 2.55d

200

82.00 ± 1.22e

400

100.00 ± 0.00f

Leaves extract

Conc. ppm

Mortality %

(Mean ± SE)LC50

(LCL–UCL.)LC90

(LCL–UCL.)LC95

(LCL–UCL.)Chi

(Sig)Regression equation

R2

Methanol

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

54.75

(48.63–61.48)156.00

(132.59–192.02)209.92

(172.87–270.73)2.260

(0.520a)Y = −4.8 + 2.77*x

0.992

25

20.00 ± 1.58b

50

42.00 ± 4.90c

100

75.00 ± 4.18d

200

95.00 ± 3.16e

400

100.00 ± 0.00e

Acetone

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

43.40

(38.72–48.22)102.62

(88.81–123.99)130.98

(110.22–165.22)3.112

(0.375a)Y = −5.26 + 3.21*x

0.988

25

24.00 ± 2.45b

50

53.00 ± 4.06c

100

89.00 ± 1.87d

200

100.00 ± 0.00e

400

100.00 ± 0.00e

Hexane

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

69.02

(60.68–78.06)225.14

(187.68–284.10)314.78

(253.15–418.36)4.622

(0.202a)Y = −4.15 + 2.24*x

0.999

25

16.00 ± 1.87b

50

36.00 ± 1.87c

100

62.00 ± 2.55d

200

85.00 ± 2.24e

400

100.00 ± 0.00f

Aqueous

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

63.76

(56.17–71.92)198.50

(166.68–248.05)273.89

(222.26–359.70)4.041

(0.257a)Y = −4.38 + 2.43*x

0.991

25

18.00 ± 2.55b

50

37.00 ± 2.00c

100

65.00 ± 4.18d

200

90.00 ± 4.18e

400

100.00 ± 0.00f

The results about the larvicidal activities of the tested T. orientalis fruits extracts against the third instar larvae of Cx. pipiens after 24 h are summarized in Table 3 and after 48 h are summarized in Table 4. The analysis of fruits extracts data revealed that the larvicidal activities after 24 h showed 100 % mortalities at 400 ppm of methanol and hexane extracts. While acetone and aqueous fruits extract at 400 ppm showed 98 % and 96 % larval mortalities, respectively. Hexane fruits extract showed the highest efficacy by inducing 100 % mortality (LC50, 68.26, LC90, 201.48, and LC95, 273.84 ppm), followed by methanol extract by 100 % mortality (LC50, 83.21, LC90, 253.85, and LC95, 348.25 ppm). The acetone extract induced 98 % mortality (LC50, 92.81, LC90, 296.34, and LC95, 411.83 ppm). While, the aqueous extract showed the least efficacy as compared to others, inducing 96 % mortality (LC50, 102.97, LC90, 333.60, and LC95, 465.54 ppm) (Table 3). The larvicidal activities of the fruits extracts after 48 h showed 100 % mortalities at 400 ppm for all tested extracts. Hexane extract showed the highest efficacy (LC50, 50.60, LC90, 119.30, and LC95, 152.14 ppm), followed by methanol extract (LC50, 68.62, LC90, 205.88, and LC95, 281.12 ppm), followed by the acetone extract (LC50, 76.43, LC90, 236.40, and LC95 (), 325.58 ppm). While, aqueous showed (LC50, 81.85, LC90, 253.48, and LC95, 349.23 ppm) (Table 4). Significance at 0.05 level between different superscripts. (a) In Chi-Square Tests, no heterogeneity factor was used in the calculation of confidence limits because the significance level was greater than 0.05. Significance at 0.05 level between different superscripts. (a) In Chi-Square Tests, no heterogeneity factor was used in the calculation of confidence limits because the significance level was greater than 0.05.

Fruit extract

Conc. ppm

Mortality%

(Mean ± SE)LC50

(LCL–UCL.)LC90

(LCL–UCL.)LC95

(LCL–UCL.)Chi

(Sig)Regression equation

R2

Methanol

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

83.21

(73.84–93.61)253.85

(212.80–317.49)348.25

(282.48–456.44)5.980

(0.113a)Y = −4.55 + 2.34*x

1.000

25

10.00 ± 1.58b

50

29.00 ± 2.92c

100

55.00 ± 4.74d

200

80.00 ± 3.16e

400

100.00 ± 0.00f

Acetone

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

92.81

(82.18–104.78)296.34

(246.13–375.30)411.83

(330.40–547.84)3.894

(0.273a)Y = −5.27 + 2.71*x

0.974

25

9.00 ± 1.00b

50

25.00 ± 1.58c

100

51.00 ± 3.32d

200

76.00 ± 2.92e

400

98.00 ± 1.22f

Hexane

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

68.26

(60.49–76.66)201.48

(170.32–249.29)273.84

(224.24–354.73)2.659

(0.447a)Y = −4.68 + 2.54*x

1.000

25

13.00 ± 2.55b

50

36.00 ± 1.00c

100

65.00 ± 4.18d

200

88.00 ± 3.00e

400

100.00 ± 0.00f

Aqueous

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

102.97

(91.14–116.45)333.60

(275.53–425.82)465.54

(371.08–624.83)2.596

(0.458a)Y = −5.18 + 2.59*x

0.987

25

7.00 ± 1.22b

50

23.00 ± 2.00c

100

46.00 ± 4.30d

200

73.00 ± 2.00e

400

96.00 ± 1.87f

Fruits extract

Conc. ppm

Mortality%

(Mean ± SE)LC50

(LCL–UCL.)LC90

(LCL–UCL.)LC95

(LCL–UCL.)Chi

(Sig)Regression equation

R2

Methanol

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

68.62

(60.74–77.16)205.88

(173.67–255.45)281.12

(229.59–365.45)3.189

(0.363a)Y = −4.56 + 2.47*x

0.999

25

14.00 ± 2.92b

50

34.00 ± 3.67c

100

66.00 ± 4.30d

200

87.00 ± 5.83e

400

100.00 ± 0.00e

Acetone

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

76.43

(67.66–86.07)236.40

(198.09–295.92)325.58

(263.83–427.56)5.274

(0.153a)Y = −4.44 + 2.34*x

0.997

25

13.00 ± 3.00b

50

31.00 ± 4.85c

100

57.00 ± 4.66d

200

84.00 ± 4.00e

400

100.00 ± 0.00e

Hexane

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

50.60

(45.43–56.07)119.30

(103.29–143.64)152.14

(128.27–190.61)4.305

(0.230a)Y = −5.21 + 3.04*x

0.994

25

18.00 ± 3.39b

50

45.00 ± 3.54c

100

82.00 ± 6.04d

200

100.00 ± 0.00e

400

100.00 ± 0.00e

Aqueous

0.0

0.00 ± 0.0a

81.85

(72.54–92.17)253.48

(212.04–317.98)349.23

(282.50–459.55)6.258

(0.100a)Y = −4.46 + 2.3*x

0.998

25

11.00 ± 1.87b

50

30.00 ± 2.24c

100

54.00 ± 2.92d

200

81.00 ± 3.32e

400

100.00 ± 0.00f

3.2 Chemical analysis

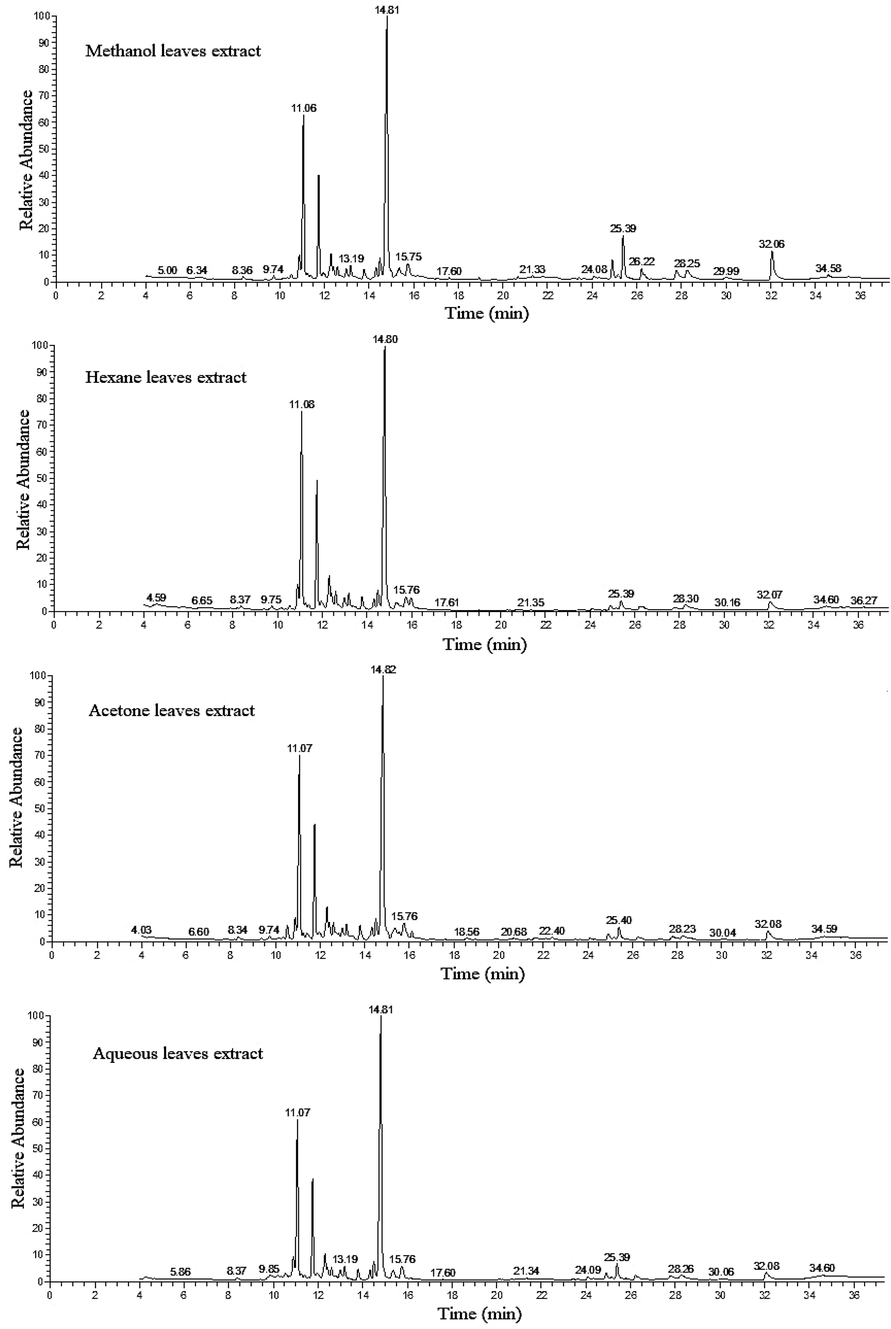

The GC–MS analysis revealed that the main constituents of the T. orientalis leaves extracts were the sesquiterpenoids and terpenoids (Table 5) and (Fig. 1). The main % area for sesquiterpenoids compounds commonly detected in all extracts, were, cedrol (33.03, 35.77, 33.99 and 38.25 %), caryophyllene (18.49, 25.31, 21.68 and 20.67 %) and humulene (10.94, 15.22, 12.28 and 12.35 %) for methanol, hexane, acetone and aqueous leaves extracts, respectively. Followed by, germacrene D (2.80, 4.00, 3.60 and 3.35 %), allocedrol (2.26, 2.22, 2.16 and 2.43 %), α-Eudesmol (1.95, 1.92, 2.91 and 2.58 %), cadina-1(10),4-diene (1.29, 1.67, 1.30 and 1.58 %), selinene (1.27, 1.18, 1.32 and 1.59 %), γ-muurolene (1.17, 1.47, 1.08 and 1.26 %), caryophyllene oxide (1.16, 1.25, 1.39 and 1.29 %), cedrene (0.39, 2.66, 0.60 and 2.33 %) and γ-elemene (0.28, 1.54, 0.62 and 1.52 %) for methanol, hexane, acetone and aqueous leaves extracts, respectively. Also, fatty acid methyl ester, cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-docosahexaenoic acid, methyl ester (1.22, 1.31, 0.29 and 0.97 %) for the same aforementioned extracts, respectively. other compounds detected in three extracts only, pimara-7,15-dien-3-ol (6.04, 1.53 and 0.54 %), α-muurolene (0.29, 1.80 and 0.31 %), alloaromadendrene (1.11, 2.11 and 0.64 %) and butyl 4,7,10,13,16,19-docosahexaenoate (3.52, 1.43 and 3.00 %) where, were detected in methanol, acetone and aqueous leaves extracts, respectively. The retinoid compound 4,14-retro-retinol represented by 1.44, 1.25 and 1.25 area % in hexan, acetone and aqueous leaves extracts, respectively. The compounds, Bornyl acetate (0.39 and 0.44 %), α-terpinyl acetate (0.48 and 0.36 %), β-elemene (0.52 and 1.73 %), 1,7-Di-epi-β-cedrene (2.47 and 2.06 %), valencen (1.05 and 1.44 %), cedarn-8-ol (0.19 and 0.14 %) and α-acorenol (1.20 and 1.64 %) were recorded in methanol and acetone leaves extracts, respectively. Meanwhile, the terpenoid compound, ehydro-4-epiabietol represented by 0.73 and 1.03 area % and the sesquiterpenoid, γ-gurjunene represented by 0.33 and 1.10 area % in acetone and aqueous leaves extracts, respectively. There are compounds were detected only in the methanol leaves extract as 4-hydroxy-3,3′,4-trimethoxystilbene (3.95 %), sugiol (1.49 %), totarol (0.52 %) and copalol (0.51 %). β-Chamigrene and linolenic acid, methyl ester were detected in hexane leaves extract and represented by 1.81 and 1.26 area %, respectively.

No

Molecular formula

Chemical compound

Methanol

(%)Hexan

(%)Acetone

(%)Aqueous (%)

Nature of compound

1

C12H20O2

Bornyl acetate

0.39

–

0.44

–

Bicyclic monoterpenoid

2

C12H20O2

α-Terpinyl acetate

0.48

–

0.36

–

Monoterpene ester monoterpenoid

3

C17H28O2

Elemyl acetate

–

–

0.75

–

Monocyclic monoterpenoid

4

C20H32O

Pimara-7,15-dien-3-ol

6.04

–

1.53

0.54

Terpenoid

5

C20H34O

Copalol

0.51

–

–

–

Terpenoid

6

C20H30O

Sugiol

1.49

–

–

–

Terpenoid

7

C20H30O

Totarol

0.52

–

–

–

Terpenoid

8

C20H30O

Dehydro-4-epiabietol

–

–

0.73

1.03

Terpenoid

9

C15H24

β-Elemene

0.52

–

1.73

–

Sesquiterpenoid

10

C15H24

1,7-Di-epi-β-cedrene

2.47

–

2.06

–

Sesquiterpenoid

11

C15H24

Caryophyllene

18.49

25.31

21.68

20.67

Sesquiterpenoid

12

C15H24

α-Muurolene

0.29

–

1.80

0.31

Sesquiterpenoid

13

C15H24

γ-Elemene

0.28

1.54

0.62

1.52

Sesquiterpenoid

14

C15H24

Humulene

10.94

15.22

12.28

12.35

Sesquiterpenoid

15

C15H24

Cedrene

0.39

2.66

0.60

2.33

Sesquiterpenoid

16

C15H24

Selinene

1.27

1.18

1.32

1.59

Sesquiterpenoid

17

C15H24

Germacrene D

2.80

4.00

3.60

3.35

Sesquiterpenoid

18

C15H24

Valencen

1.05

–

1.44

–

Sesquiterpenoid

19

C15H24

γ-Muurolene

1.17

1.47

1.08

1.26

Sesquiterpenoid

20

C15H24

Cadina-1(10),4-diene

1.29

1.67

1.30

1.58

Sesquiterpenoid

21

C15H24

Alloaromadendrene

1.11

–

2.11

0.64

Sesquiterpenoid

22

C15H24

Cedrenol

–

–

–

0.20

Sesquiterpenoid

23

C15H24

Aromandendrene

–

–

–

1.65

Sesquiterpenoid

24

C15H24O

Caryophyllene oxide

1.16

1.25

1.39

1.29

Sesquiterpenoid

25

C15H26O

Allocedrol

2.26

2.22

2.16

2.43

Sesquiterpenoid

26

C15H26O

Cedrol

33.03

35.77

33.99

38.25

Sesquiterpenoid alcohol

27

C15H26O

Cedran-8-ol

0.19

–

0.14

–

Sesquiterpenoid

28

C15H26O

α -acorenol

1.20

–

1.64

–

Sesquiterpenoid

29

C15H26O

α-Eudesmol

1.95

1.92

2.91

2.58

Cycloeudesmane sesquiterpene

30

C15H24

β-Chamigrene

–

1.81

–

–

Sesquiterpenoid

31

C15H24

γ-Gurjunene

–

–

0.33

1.10

Sesquiterpenoid

32

C19H32O2

Linolenic acid, methyl ester

–

1.26

–

–

Fatty acid methyl ester

33

C23H34O2

cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-Docosahexaenoic acid, methyl ester

1.22

1.31

0.29

0.97

very long-chain fatty acid methyl ester

34

C26H40O2

Butyl 4,7,10,13,16,19-docosahexaenoate

3.52

–

1.43

3.00

very long-chain fatty acid

35

C17H18O4

4-Hydroxy-3,3′,4-trimethoxystilbene

3.95

Stilbene polyphenol

36

C20H30O

4,14-retro-retinol

–

1.44

1.25

1.25

Retinoid

The TIC chromatograms of leaves, methanol, hexane, acetone and aqueous extracts from Thuja orientalis showing chemical constituents separation detected by GC–MS.

Elemyl acetate compound detected in acetone leaves extract only and represented by 0.75 area %. Cedrenol and aromandendrene compounds detected in aqueous leaves extract only and represented by 0.20 and 1.65 area %, respectively.

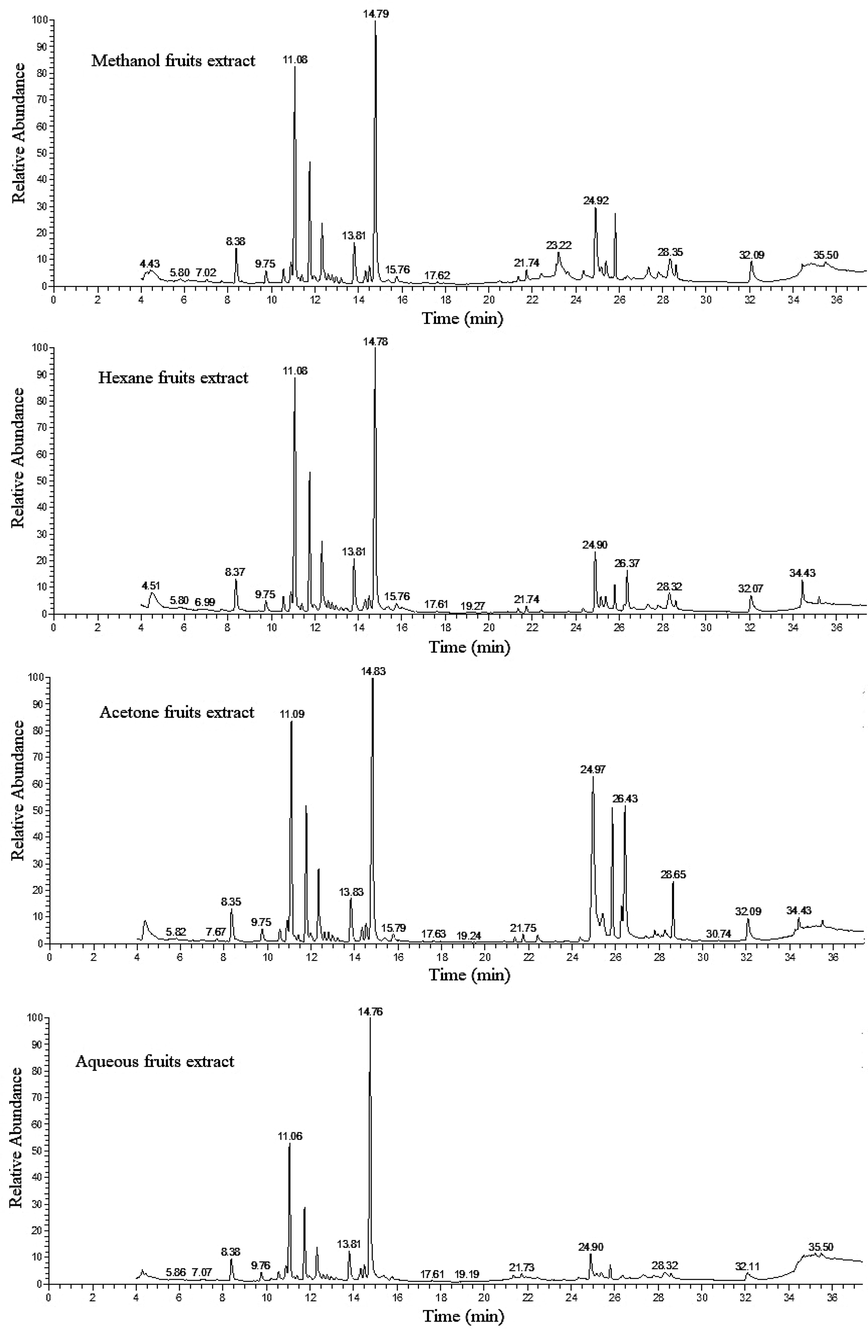

The GC–MS analysis revealed that the main constituents of the fruits extracts were represented in Table 6 and (Fig. 2). The main commonly sesquiterpenoids compounds in all extracts were, cedrol (21.26, 25.11, 18.55 and 36.66 %) and caryophyllene (17.06, 19.93, 15.21 and 17.04 %) for methanol, hexane, acetone and aqueous fruits extracts, respectively. Followed by the compounds, humuline (9.05, 10.93, 8.62 and 9.06 %), germacrene D (4.93, 5.76, 5.16 and 4.44 %), elemol (4.20, 4.57, 3.42 and 4.05 %), bornyl acetate (3.14, 3.08, 2.48 and 3.35 %), terpinolene (1.14, 2.75, 1.77 and 1.62 %), α-terpinyl acetate (1.10, 0.93, 1.10 and 1.22 %), cedrene (1.45, 1.36, 1.22 and 1.44 %), allocedrol (1.48, 1.18, 1.26 and 1.84 %), β-elemene (1.15, 1.28, 0.86 and 1.07 %), caryophyllene oxide (1.08, 1.14, 1.04 and 1.62 %), selinene (0.60, 0.59, 0.56 and 0.65 %) for methanol, hexane, acetone and aqueous fruits extracts, respectively. Two compounds were detected in three extracts only, labda-8(20),12,14-triene (4.64, 1.80 and 8.02 %) and trachyloban (0.81, 0.63 and 0.52 %), in methanol, hexan and acetone fruits extracts, respectively. Alloaromadendrene recorded in methanol and acetone fruits extracts by 0.48 and 0.53 area%, respectively. While, γ-elemene detected in methanol, hexane and aqueous extracts by 0.51, 0.53 and 0.42 area %, respectively. Isopimaral and olic acid detected in hexan and acetone extracts by 5.64, 5.64 and 2.02 and 0.76 area %, respectively. cis-5,8,11,14,17-eicosapentaenoic acid, methyl ester represented by 7.11 and 3.48 area %, i-Propyl 7,10,13,16,19-docosapentaenoate represented by 2.26 and 2.26 area %, arachidonic acid methyl ester represented by 0.58 and 1.13 area %, 6,9,12,15-docosatetraenoic acid, methyl ester represented by 0.63 and 1.89 area %, dodecanoic acid, 2,3-bis(acetyloxy)propyl ester represented by 0.76 and 0.42 area %, and in methanol and aqueous extracts, respectively. β-Eudesmol compound detected in hexane and aqueous fruits extracts and represented by by 0.80 and 0.70 area %, respectively.

No

Molecular formula

Chemical compound

Methanol (%)

Hexan (%)

Acetone (%)

Aqueous (%)

Nature of compound

1

C10H16

Terpinolene

1.14

2.75

1.77

1.62

Menthane monoterpenoid

2

C10H16

2-Carene

1.00

–

–

–

Bicyclic monoterpenoid

3

C20H32

Labda-8(20),12,14-triene

4.64

1.80

8.02

Terpenoid

4

C21H32O2

Labda-8(20) 12 14-triene-19-oic acid methyl ester (z)-

–

2.95

–

–

Terpenoid

5

C21H34O

Labda-8(20),14-dien-13-ol, (13S)-

–

–

–

1.62

Terpenoid

6

C20H32

(-)-Atisirene

0.42

–

–

–

Terpenoid

7

C20H32

Trachyloban

0.81

0.63

0.52

–

Terpenoid

8

C12H20O2

Bornyl acetate

3.14

3.08

2.48

3.35

Bicyclic monoterpenoid

9

C12H20O2

α-Terpinyl acetate

1.10

0.93

1.10

1.22

Monoterpene ester

10

C20H28O6

16-Hydroxyingenol

0.45

–

–

–

Terpenoid

11

C20H30O2

Communic Acid

0.93

–

–

–

Terpenoid

12

C20H32O

Pimara-7,15-dien-3-ol

–

–

1.46

–

Terpenoid

13

C23H38O2Si

Pimaric acid TMS derivative

–

–

8.43

–

Terpenoid

14

C23H38O2Si

Isopimaric acid TMS ester

–

–

–

–

Terpenoid

15

C20H30O

Isopimaral

–

5.64

5.64

–

Terpenoid

16

C20H34O

Copalol

–

1.05

–

–

Terpenoid

17

C20H30O

Totarol

–

–

–

–

Terpenoid

18

C20H30O

Dehydro-4-epiabietol

–

–

–

–

Terpenoid

19

C21H32O2

Isopimaric acid, methyl ester

–

1.00

–

–

Terpenoid

20

C15H24

β-Elemene

1.15

1.28

0.86

1.07

Sesquiterpenoid

21

C15H24

γ-Elemene

0.51

0.53

–

0.42

Sesquiterpenoid

22

C15H24

δ-EIemene

0.68

–

–

–

Sesquiterpenoid

23

C15H24

1,7-Di-epi-β-cedrene

–

–

–

Sesquiterpenoid

24

C15H24

Caryophyllene

17.06

19.93

15.21

17.04

Sesquiterpenoid

25

C15H24

Humulene

9.05

10.93

8.62

9.06

Sesquiterpenoid

26

C15H24

Cedrene

1.45

1.36

1.22

1.44

Sesquiterpenoid

27

C15H24

Selinene

0.60

0.59

0.56

0.65

Sesquiterpenoid

28

C15H24

Germacrene D

4.93

5.76

5.16

4.44

Sesquiterpenoid

29

C15H24

Isogermacrene D

0.31

–

–

–

Sesquiterpenoid

30

C15H24

Valencen

–

–

–

1.05

Sesquiterpenoid

31

C15H24

Cadina-1(10),4-diene

0.47

–

–

–

Sesquiterpenoid

32

C15H24

Alloaromadendrene

0.48

–

0.53

–

Sesquiterpenoid

33

C15H24

Chamigrene

–

0.61

–

–

Sesquiterpenoid

34

C20H32

Cubenol

–

–

–

1.48

Sesquiterpenoid

35

C15H24O

Caryophyllene oxide

1.08

1.14

1.04

1.62

Sesquiterpenoid

36

C15H26O

Allocedrol

1.48

1.18

1.26

1.84

Sesquiterpenoid

37

C15H26O

Cedrol

21.26

25.11

18.55

36.66

Sesquiterpenoid alcohol

38

C15H26O

α-Eudesmol

0.64

–

–

–

Cycloeudesmane sesquiterpene

39

C15H26O

β-Eudesmol

–

0.80

–

0.70

Cycloeudesmane sesquiterpene

40

C15H26O

Elemol

4.20

4.57

3.42

4.05

Sesquiterpenoid

41

C17H18O4

1-Heptatriacotanol

0.95

–

–

–

Fatty alcohol

42

C18H34O2

Oleic Acid

–

2.02

0.76

–

Fatty acid

43

C18H30O2

10-Heptadecen-8-ynoic acid, methyl ester,(E)-

–

–

–

0.49

Fatty acid methyl ester

44

C19H34O6

Dodecanoic acid, 2,3-bis(acetyloxy)propyl ester

0.76

–

–

0.42

Lauric fatty acid ester with hydroxypropanediyl diacetate

45

C19H30O2

13,16-Octadecadiynoic acid, methyl ester

3.24

–

–

–

Fatty acid methyl ester

46

C19H32O2

6,9,12-Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester

–

–

0.62

Fatty acid methyl ester

47

C21H34O2

Arachidonic acid methyl ester

0.58

–

–

1.13

Fatty acid methyl ester

48

C21H32O2

cis-5,8,11,14,17-Eicosapentaenoic acid, methyl ester

7.11

–

–

3.48

Fatty acid methyl ester

49

C21H36O2

Linolenic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester (Z,Z,Z)-

0.29

–

–

–

Fatty acid ethyl ester

50

C23H36O2

7,10,13,16,19-docosapentaenoic acid, methyl ester

–

–

–

0.81

Fatty acid ethyl ester

51

C22H32O2

Doconexent

1.42

–

–

–

very long-chain fatty acid

52

C23H34O2

cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-Docosahexaenoic acid

0.84

–

–

–

very long-chain fatty acid

53

C25H40O2

i-Propyl 7,10,13,16,19-docosapentaenoate

2.26

–

–

2.26

very long-chain fatty acid

54

C23H38O2

6,9,12,15-Docosatetraenoic acid, methyl ester

0.63

–

–

1.89

very long-chain fatty acid methyl ester

55

C21H36O4

9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester, (Z,Z,Z)-

0.59

–

–

1.24

1-monoglyceride derives from α-linolenic acid

56

C21H38O2Si

α-Linolenic acid, TMS derivative

–

–

12.23

–

Fatty acid trimethyl ester

57

C23H38O2Si

Eicosapentaenoic acid, TMS derivative

–

–

1.81

–

Fatty acid trimethyl ester

58

C21H34

Androst-5-ene, 4,4-dimethyl-, (13à)-

1.85

–

–

–

Steroid

59

C21H34O2

Androstan-17-one, 3-ethyl-3-hydroxy-, (5à)-

–

0.60

–

–

Steroid

60

C27H42O3

Pseduosarsasapogenin-5,20-dien

0.54

Steroidal saponin

61

C17H18O4

4-Hydroxy-3,3′,4-trimethoxystilbene

Stilbene polyphenol

62

C20H30O

4,14-retro-retinol

1.45

1.71

Retinoid

63

C20H28O6

Dotriacontane

0.45

Alkane

The TIC chromatograms of fruits, methanol, hexane, acetone and aqueous extracts from Thuja orientalis showing chemical constituents separation detected by GC–MS.

There are 15 compounds detected only in methanol fruits extract only which were, 13,16-octadecadiynoic acid, methyl ester (3.24 %), Androst-5-ene, 4,4-dimethyl-, (13à)- (1.85), doconexent (1.42 %), 2-Carene (1.00 %), 1-heptatriacotanol (0.95 %), communic acid (0.93 %), cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-docosahexaenoic acid (0.84 %), δ-eIemene (0.68 %), α-eudesmol (0.64 %), Pseduosarsasapogenin-5,20-dien (0.54 %), Cadina-1(10),4-diene (0.47 %), 16-hydroxyingenol (0.45), (-)-Atisirene (0.42 %), isogermacrene D (0.31 %), linolenic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester (Z,Z,Z)-(0.29 %). Six compounds detected only in hexane fruits extract which were, labda-8(20) 12 14-triene-19-oic acid methyl ester (z)-(2.95 %), copalol (1.05 %), isopimaric acid, methyl ester (1.00 %), chamigrene (0.61 %), Androstan-17-one, 3-ethyl-3-hydroxy-, (5à)-(0.60 %) and Dotriacontane (0.45 %). Four compounds detected only in acetone fruits extract were, α-linolenic acid, TMS derivative (12.23 %), pimaric acid TMS derivative (8.43 %), eicosapentaenoic acid, TMS derivative (1.81 %) and pimara-7,15-dien-3-ol (1.46 %). While, in aqueous fruits extract there are six compounds detected which were, labda-8(20),14-dien-13-ol, (13S)- (1.62 %), valencen (1.05 %), cubenol (1.48 %), 7,10,13,16,19-docosapentaenoic acid, methyl ester (0.81 %), 6,9,12-octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester (0.62 %) and 10-heptadecen-8-ynoic acid, methyl ester,(E)- (0.49 %) (Table 6) and (Fig. 2).

4 Discussion

Generally the study reviled larvicidal activities of T. orientalis leaves and fruits extracts in a concentration dependent manner whatever the activities varied between leaves and fruits tested extracts. Leaves extracts ordered according to larval toxicity as acetone > methanol > aqueous > hexane. While, fruits extracts ordered as hexane > methanol > acetone > aqueous. Collectively acetone T. orientalis leaves extract showed throughout the tested extracts, the most effective larvicidal activity against C. pipiens larvae (100 % mortality) and (LC50, 58.04 ppm LC90, 169.27 ppm LC50, 229.27 ppm) at concentration 400 ppm.

Different Plant extracts previously tested for their larvicidal activities against mosquitoes, El-Sheikh et al. (2012) tested the larval toxicity of ethanol, acetone and petroleum ether extracts of Tribulus terrestris leaves, against the third instar larvae Ae. aegypti and predicted dose dependent larvicidal activities for the tested extracts in addition to variation of larvicidal activities related to solvent used. Where, crude plant extracts showed previously more efficiency in controlling mosquitoes over the purified compounds toxicity, which in line with the present study results (Ghosh et al., 2012). Another study estimated larval toxicity of leaves aqueous extracts in three tested concentrations from Ricinus communis L. (0.06, 0.12 and 0.2 g/l), Daphne gnidium L (0.09, 0.18 and 0.3 g/l) and Thymus vulgaris L. (0.0225, 0.045 and 0.09 g/l), against early instar larvae of Cx. pipiens and Cs. Longiareolata and showed in line with the present study results that the larval mortality increased with exposure times (24, 48 and 72 h), and the LC50 recorded values decreased in the same manner (Dahchar et al., 2016).

The chemical compounds detected in the extracts in line with that detected in previous studies, however, there were differences in the amount or number of the main components (Elsharkawy et al., 2017; Guleria et al., 2008; Nickavar et al., 2003; Ololade et al., 2014; Sanei-Dehkordi et al., 2018).

The common sesquiterpenoids highly represented as % areas in the chromatograms of all tested leaves and fruits extracts were, Cedrol, Caryophyllene, Humulene, Germacrene D and Elemol (common only in fruits extracts). The medium common ones were, γ-Elemene, Cedrene, Selinene, γ-Muurolene, Cadina-1(10),4-diene, Caryophyllene oxide, Allocedrol, α-Eudesmol and the fatty acid methyl ester, cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-Docosahexaenoic acid, methyl ester in leaves extracts and bornyl acetate, α-Terpinyl acetate, Cedrene, β-Elemene, Selinene and Caryophyllene oxide were medium common in fruits extracts. The observed larvicidal activities of the tested extracts may related to their chemical constituents synergistic actions, either the major or minor ones that may impact on the predicted larvicidal activities (Huong et al., 2020).

The essential oil P. orientalis L. (Family Cupressaceae) oil showed insecticide and molluscicidal activity (Hashemi and Safavi 2012; Ju-Hyun et al., 2005; Lei, et al., 2010). Thuja orientalis previously acquired cytotoxic principles and contained terpenoids including pimaric and isopimaric acids, fatty acids, aliphatic compounds like alkanes and bioflavonoids (Mehta et al., 1999). The essential oil extracted from T. orientalis leaves predicted larvicidal activity against Anopheles stephensi and Culex pipiens late third or young 4th instar larvae, where carene and cedrol were from the main constituents of the extract (Sanei-Dehkordi et al., 2018). Also extracts predicted diterpenes and labdane-type diterpenes in line with the previously recorded (Kim et al 2012; Kim et al., 2013). Cedrol the main constituent in the tested extracts was postulated as alternative to conventional synthetic acaricides for the black-legged ticks, Ixodes scapularis Say which is a human vector causing disease (Eller et al., 2014). Caryophyllene oxide and germacrene D individual compounds previously showed potent larvicidal activities against A. anthropophagus (Zhu and Tian, 2013). Also β-elemene and α-humulene showed larvicidal activities against A. subpictus, Ae albopictus, and Cx. tritaeniorhynchus (Govindarajan and Benelli, 2016). Jeon et al. (2005) showed that essential oils extracted from P. orientalis had strong activities on mosquito larvae Cx. pipiens and Ae. aegypti recording 100 % mortality at 400 ppm. Furthermore, Sanei-Dehkordi et al. (2018) verified the high efficiency of P. orientalis oil against A. stephensi (LC50, 11.67 ppm) and Cx. pipiens (LC50, 18.60 ppm). Ethanol and acetone leaves extracts of T. orientalis previously evaluated larvicidal activities against mosquitoes recording LC50, 13.10 and 200.87 ppm after 24 h and 9.02 and 127.53 ppm after 48 h, against A. stephensi third instar larvae, respectively. Besides recording against C. quinquefasciatus third instar larvae, LC50, 22.74 and 69.03 ppm after 24 h and 16.72 and 51.14 ppm after 48 h, respectively (Sharma et al., 2005).

In addition and in accordance with the present results behavior, hexane plant parts and seeds extracts of Physalis angulate, Peganum harmala, Tecrium polium and Thymus vulgaris were evaluated for their larvicidal potentials against the fourth instar larvae of Culex pipiens molestus, and showed that mortality increased with exposure times (24 and 48 h) and the LC50 recorded values decreased with exposure times (Mekhlif and Muhammad, 2021). A study tested larvicidal activities leaves oils extracts against A. aegypti and recorded that the main components in leaves of G. blepharophylla was the caryophyllene oxide, while, in G. friesiana were α-,β- and γ-eudesmols and in G. hispida, was (E)-caryophyllene. According to the predicted results oil extracted from G. friesiana recorded the best larvicidal effect against A. aegypti and hypothesized that sesquiterpenes in oils can reflect more controlling activity as compared to monoterpenes (Aciole et al., 2011). The aforementioned study results may declare the predicted advantage of acetone leaves extract results where the extract acquired highest content of eudesmol as compared to other extracts.

5 Conclusion

The leaves and fruits methanol, hexane, acetone and aqueous extracts of T. orientalis reviled high larvicidal potential at 400 ppm concentration against the third instar larvae of Cx. pipiens with the advantage of leaves acetone extract that predicted the lowest effective larval toxicity concentration. Further studies about the mode of the larvicidal action of the extracts should be under investigation.

Authorship contribution

Author declare her acknowledgment to the Center for Environmental Research and Studies at Jazan University for the technical support.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Author declare her acknowledgment to the Center for Environmental Research and Studies at Jazan University for the technical support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol.. 1925;18(2):265-267.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Insecticidal activity of three species of Guatteria (Annonaceae) against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Rev. Colomb. Entomol.. 2011;37:262-268.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N., Alam, M., Saeed, M., Ullah, H., Iqbal, T., Al-Mutairi, K.A., Shahjeer, K., Ullah, R., Ahmed, S., Ahmed, N.A.A.H., Khater, H.F., Salman, M., 2021. Botanical Insecticides Are a Non-Toxic Alternative to Conventional Pesticides in the Control of Insects and Pests, in: Global Decline of Insects. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.100416.

- Thuja occidentalis L. (Cupressaceae): Ethnobotany, phytochemistry and biological activity. Molecules. 2020;25(22):5416.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Growth suppression of a gingivitis and skin pathogen Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium) acnes by medicinal plant extracts. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2021;10(9):1092.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity of some plant extracts against two mosquito species Culex pipiens and Culiseta longiareolata. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud.. 2016;4:346-350.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical profiling and identification of anti-inflammatory biomarkers of oriental Thuja (Platycladus orientalis) using UPLC/MS/MS and network pharmacology-based analyses. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2021;1–5

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bioactivity of cedarwood oil and cedrol against arthropod pests. Environ. Entomol.. 2014;43(3):762-766.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of drought condition of North Region of Saudi Arabia on accumulation of chemical compounds, antimicrobial and larvicidal activities of Thuja Orientalis. Orient. J. Chem.. 2019;35(2):738-743.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of antioxidant and anticancer activity of Thuja orientalis growing in Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Br. J. Pharm. Res. 2017;15:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Insecticidal and repellent activities of methanolic extract of Tribulus terrestris L. (Zygophyllaceae) against the malarial vector Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae). Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. A, Entomol.. 2012;5:13-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Bird biting” mosquitoes and human disease: a review of the role of Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes in epidemiology. Infect. Genet. Evol.. 2011;11:1577-1585.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plant extracts as potential mosquito larvicides. Indian J. Med. Res.. 2012;135(5):581-598. PMID: 22771587

- [Google Scholar]

- α-Humulene and β-elemene from Syzygium zeylanicum (Myrtaceae) essential oil: highly effective and eco-friendly larvicides against Anopheles subpictus, Aedes albopictus, and Culex tritaeniorhynchus (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res.. 2016;115:2771-2778.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eugenol, α-pinene and β-caryophyllene from Plectranthus barbatus essential oil as eco-friendly larvicides against malaria, dengue and Japanese encephalitis mosquito vectors. Parasitol. Res.. 2016;115(2):807-815.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and fungitoxic activity of essential oil of Thuja orientalis L. grown in the north-western Himalaya. Zeitschrift für Naturforsch. C. 2008;63:211-214.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents and toxicity of essential oils of oriental arborvitae, Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco, against three stored-product beetles. Chil. J. Agr. Res.. 2012;72(2):188-194.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquito larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Zingiber collinsii against Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Oleo Sci.. 2020;69(2):153-160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity of Chamaecyparis obtusa and Thuja orientalis leaf oils against two mosquito species. J. Appl. Biol. Chem.. 2005;48(1):26-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity of Chamaecyparis obusta and Thuja orientalis leaf oils against two mosquito species. Agric. Chem. Biotech.. 2005;48(1):26-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Three new diterpenoids from the leaves of Thuja orientalis. Planta Med.. 2012;78:485-487.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.-H., Li, H., Wu, Q., Lee, H.J., Ryu, J.-H., 2013. A new labdane diterpenoid with anti-inflammatory activity from Thuja orientalis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 146, 760–767. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.02.001.

- Composition and variability of essential oils of Platycladus orientalis growing in China. Biochem. Syst. Ecol.. 2010;38(5):1000-1006.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of novel compounds from Thuja orientalis (leaves) Indian J. Chem. - B Org Med. Chem.. 1999;38(8):1005-1008.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal potentials of four medicinal plant extracts on mosquito vector, Culex pipiens molestus (Diptera: Culicidae) Int. J. Mosq. Res.. 2021;8(4):01-05.

- [Google Scholar]

- Towards eco-friendly crop protection: natural deep eutectic solvents and defensive secondary metabolites. Phytochem. Rev.. 2017;16:935-951.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Volatile constituents of the fruit and leaf oils of Thuja orientalis L. grown in Iran. Zeitschrift für Naturforsch.. 2003;C 58(3–4):171-172.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of water and alcohol extracts of Thuja orientalis leaves. Adv. Tradit. Med.. 2007;7:65-73.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical and Therapeutic Studies of the Fruit essential oil of Thuja orientalis from Nigeria. Glob. J. Sci. Front. Res. B Chem. 2014;14(7):14-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil composition and larvicidal evaluation of Platycladus orientalis against two mosquito vectors, Anopheles stephensi and Culex pipiens. J. Arthropod. Borne. Dis.. 2018;12(2):101-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal potential of Nerium indicum and Thuja oriertelis extracts against malaria and Japanese encephalitis vector. J. Environ. Biol.. 2005;26(4):657-660.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thuja orientalis reduces airway inflammation in ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma. Mol. Med. Rep.. 2015;12:4640-4646.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biological properties of Thuja orientalis Linn. Adv. Life Sci.. 2012;2:17-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for laboratory and field testing of mosquito larvicides. World Health Organization 2005:1-41. Retrieved from

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2013). Larval source management: a supplementary malaria vector control measure, 1–2. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85379/9789241505604_eng.pdf.

- The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.. 2020;14:e0007831.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hair growth-promoting activity of hot water extract of Thuja orientalis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.. 2013;13:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and larvicidal activity of essential oil of Artemisia gilvescens against Anopheles anthropophagus. Parasitol. Res.. 2013;112(3):1137-1142.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102396.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: