Translate this page into:

Larvicidal activity of plant extracts by inhibition of detoxification enzymes in Culex pipiens

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objectives

Plant extracts have been a safe and eco-friendly substituent of chemical pesticides, used against mosquitoes to prevent vector-borne infections e.g., chikungunya, yellow fever, dengue, filariasis, dirofilariasis tularemia, malaria, and many other diseases.

Methods

The larvicidal activities of the acetone extracts of four plants e.g., Lantana camara, Ruta chalepensis, Rhazya stricta, and Acalypha fruticosa was evaluated against Culex pipiens. The composition secondary metabolites of the most effective extract (L. camara) was examined using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS). The expression level of Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and Glutathione S-transferase (GST) genes were assessed through qRT-PCR.

Results

The results revealed that the extract of L. camara caused 98% mortality in Cx. pipiens followed by R. stricta (91%), A. fruticosa (79%), and R. chalepensis (69%) as compared to azadirachtin, used as a positive control. The results showed that LD50 and LD90 of the extract of L. camara were significantly higher as compared to R. stricta, A. fruticosa, and R. chalepensis extract. The extract of L. camara also significantly reduced the activities of AChE and GST as compared to the larvae, treated with the extracts of another plant extracts as well as a positive control. The chemical composition of L. camara, was determined through GC–MS.

Conclusions

The most important insecticidal compounds were including undecane, terephthalic acid, dimethyl-propane-thiosulfinate, fluorobenzoic acid octadecenoic acid. The insecticidal activity of the L. camara extracts against Cx. pipiens might be due to one or more of these compounds.

Keywords

Plant Extracts

Culex pipiens

Metabolites profile

Acetylcholinesterase

Glutathione S-transferases

1 Introduction

Mosquitoes are the most important pest, cause several infectious diseases e.g., dengue, chikungunya, malaria, filariasis, yellow fever, dirofilariasis tularemia, and many other diseases. Culex pipiens are common house mosquito which transmits several infections for example West Nile fever, Sindbis fever, lymphatic filariasis, and Japanese encephalitis (Brugman et al., 2018). Cx. pipiens pipiens and Cx. pipiens pallens are the two subspecies of Cx. pipiens (Yang et al., 2004). Female Cx. pipiens normally feed on the blood of vertebrae including human beings and birds and hence transmits infectious diseases from birds to humans and from humans to humans. Eggs are laid in clumps on the surface of stagnant water bodies, such as pools, ditches, water tanks, and vases (Jang et al., 2020). The diseases transmitted by Cx. pipiens cause tens of thousands of deaths annually. Moreover, a majority of these diseases, for instance, West Nile fever, St Louis encephalitis, and lymphatic filariasis are not vaccine-preventable in humans (Rehman et al., 2019). Therefore, pest management remains an indispensable tool in the control and prevention of mosquito-borne infections.

Although Lantana camara is an ornamental plant, it is considered an invasive species in agricultural areas (Ghisalberti, 2000). L. camara is a valuable source of biologically active compounds, and phytochemical studies have shown the metbolites including terpenoids, phenylethanoid glycosides, flavonoids, and flavonoids are present in L. camara. Antifungal, antiprotozoal, antibacterial antiviral, allelopathic properties, antioxidant, activities of the metabolites extracted from L. camara has been detected (Elumalai et al., 2017). Ruta chalepensis is another small perennial shrub, used for the treatment of fever and joint pain in indigenous Arabic medicine (Günaydin and Savci, 2005). R. chalepensis is a flowering plant evergreen herb that grows up to 80 cm tall. Because of the variety of biological activities caused by their secondary metabolites, including antifungal, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, Rutaceae species have attracted a great deal of interest. In the Mediterranean region, one of the widely distributed species is R. Chalepensis, usually referred to as fringed rue. The plant abounds in alkaloids and is well-known for its antioxidant properties (Elumalai., 2017). Acalypha fruticosa is also very well-known medicinal plant, belongs to the spurge family of Angiosperms. Dried leaves of A. fruticosa are used for making tea in Ethiopia. Furthermore, the leaf extracts of plants also show growth inhibition of agricultural pests (Lingathurai et al., 2011). A. fruticosa has been used extensively as a repellent or insecticide against ectoparasites and flies and also used as food, fodder. The powder of the dried leaves, soak in water is used heal the skin of animals. Rhazya stricta is known to possess some biological activity against insects and used in folk medicine. It was shown to be rich in alkaloids of different types, flavonoids, sterols and volatile oil. R. stricta possess a strong antimicrobial activity and also possess bioactive molecules such as alkaloids, terpenoids, antioxidants.

The insects manage the toxicity through their antioxidant defense mechanism, which consists of both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant components (Turhan et al., 2020; Türkan et al., 2020). Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are multifunctional enzymes that play a central role in the detoxification of both endogenous and xenobiotic compounds and protection against the toxicity (Taslimi and Gulçin, 2018; Gülçin et al., 2020b).

In the present study, the pesticidal activity of acetone extracts from L. camara, R. chalepensis, R. stricta, and A. fruticosa leaves was tested against Cx. pipiens. The basic aim of the study was to compare the insecticidal activities of the four plats and to identify the most significant plant against the Cx. pipiens. moreover, the study was also aimed to determine the capability to overcome the antioxidant enzymes such as AChE and GST in larvae which are produced and withstand the toxicity.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Reproduction of Cx. Pipiens

The Cx. pipiens larvae have been collected from the laboratory for mosquito studies from the Mosquito Research Laboratory, King Abdulaziz University Saudi Arabia. The larvae were reared on artificial food, added in containers (25 × 35 × 6 cm) filled water. The colony was maintained under the following conditions: 27 °C ± 2 °C, 70% ± 5% R.H.

2.2 Collection and processing of plant material

The plants used in the study, i.e., L. camara, R. chalepensis, R. stricta, and A. fruticosa, were collected from different places in Saudi Arabia. The leaves were plucked, washed with tap water, and shade dried for a few days. Finally, the dried leaves were ground to a fine powder with the help of a laboratory grinder (Philips, Germany).

2.3 Preparation of extract of different plants

Exactly 40–60 g of leaf powder was added to a Soxhlet apparatus, along with 200 ml of absolute acetone. The extraction continued for six hours. The extracts were then concentrated in a rotary evaporator until they became considerably viscous. To prepare the stock solutions, 1 ml of acetone extracts were mixed with 99 ml of 0.3% dimethyl-sulphoxide (prepared in distilled water). Finally, 100, 300, 500, 700, and 1000 mg/l of working solutions were made in distilled water.

2.4 Larvicidal bioassay of different plants against Cx. Pipiens

After preparing the aforementioned concentrations of the plant extract, each preparation was added to 250 ml glass beakers. Then 25 early fourth instar larvae were introduced in each assembly. Experiments were run in quadruplicates. The larvae were given standard larval food and the temperature was kept 28 ± 2 °C. After 24 h of exposure, percentage mortality was noted. Thenceforth, cumulative mortalities of larvae and pupae were documented daily. Live pupae were transferred to new beakers containing fresh water. Partially emerged adults or adults who failed to leave the water surface were not considered viable (Maheswaran et al., 2008). Negative and positive control reactions were conducted. In the positive control, 1% of Azadirachtin was used. LC50 and LC90 of the plant extracts were also calculated using probit analysis.

2.5 Assessment of AChE in larvae

Acetylthiocholine was used to evaluate the AChE activity as described by Ellman et al. (1961). Five heads of the mosquito larvae were homogenized in a solution containing 1 ml Triton X-100, 38.03 mg ethylene glycol tetra-acetic acid (EGTA), 5.845 g NaCl, and 80 ml Tris buffer (10 mM, pH 7). At 5000 rpm, the homogenate was centrifuged for 5 min and 100 μl of supernatant was added to 1 ml of Tris (0.1 M, pH 8), 100 μl of 5–5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DNTB) in Tris (0.01 M, pH 8) buffer. 100 μl acetylthiocholine was added after 5 min. The activity of AChE was measured by a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan) at 412 nm (Topal et al., 2017; Cakmak and Gülçin, 2019; Aras et al., 2019; Gülçin et al., 2020a).

2.6 Analysis of GST activity in larvae

The decapitated larvae were homogenized in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6, centrifuged for 30 min at10,000 rpm and activity the GST was assessed as described by Gülçin et al., (2016a) Absorption changes were recorded at 340 nm by means of spectrophotometers (Shimadzu, Japan). According to Bradford (1976), the protein content was evaluated using bovine serum albumin as the standard (BSA, Sigma).

2.7 Identification of compounds through GC–MS analysis

The plant selected has been dried and crushed into a fine powder using mortar and pestle. During the drying and extraction of plant metabolites, proper action was taken to ensure that bioactive constituents were not lost or destroyed. Using acetone, the extraction was carried out and the extract was filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. At a split ratio of 10:1, exactly 2 μl of sample volume was injected into GC–MS (Agilent Technologies, USA). The helium gas (He) was used at a flow rate of 1 ml/min as a carrier gas. The column was set at 60 °C for 2 min and then increased to 160 °C for 5 min at a rate of 5 °C/min. In the electron ionization system, in electron impact mode, the ionization energy to detect the ions was 70 eV. Compared with the library present in the NIST library was the spectrum of detected compounds in the extract.

2.8 Statistical analysis

The results were presented as mean ± SD, and to perform statistical analyses, MS office Excel 2016 was used. DMRT was performed using the Statistic Analysis Method (SAS 9.1, USA) to detect major variations between treatments and controls.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Larvicidal, pupicidal and emergence inhibition bioassay of different plant extract

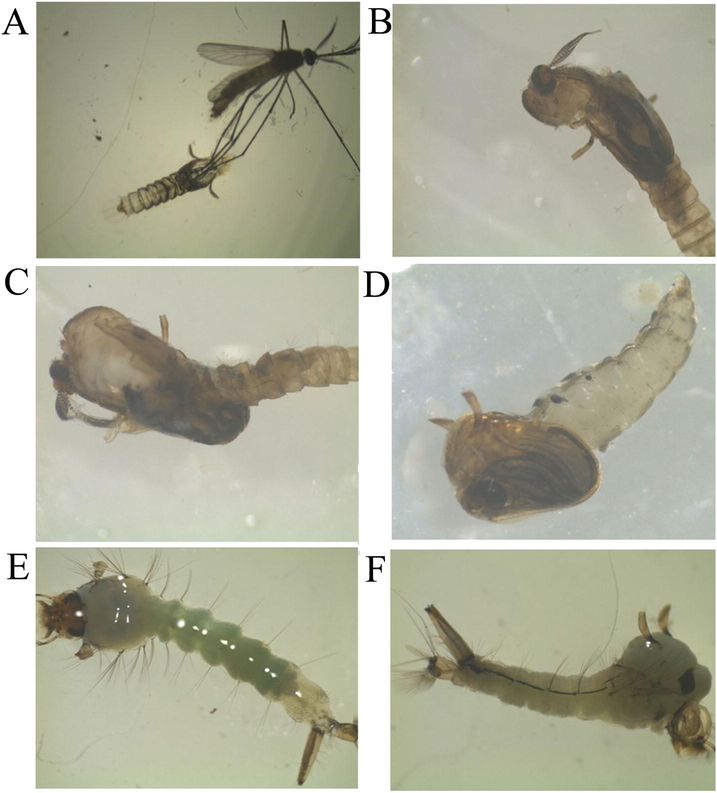

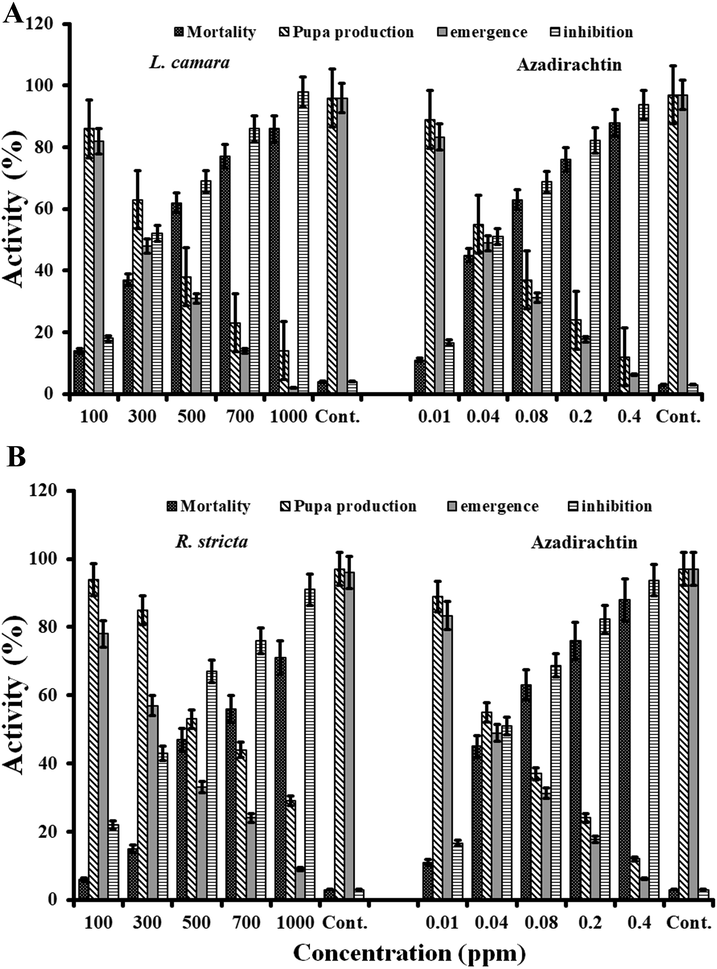

The compounds are often inexpensive, biodegradable, and highly effective, therefore they are used frequently against the pest (Ahmed et al., 2016). The results of our study showed that the larvicidal activity of L. camara extract was 14% when 100 mg/l concentration was applied. However, the mortality was increased up to 98% when 1000 mg/l concentration was applied. Interestingly, fewer adults emerged from the surviving pupae, as we increased the concentration of the plant extract. This indicated that the plant extract is highly toxic for the pupae, caused incomplete emergence of an adult from a pupa (Fig. 1A and 1B). The extract of the L. camara caused inhibition of pupa production from larvae (Fig. 1C and 1D) and also caused larvae deformities (Fig. 1E and 1F). The total percentage inhibition, observed at 1000 mg/l was up to 98% (Fig. 2A).

(A) Incomplete emergence of the adult mosquito from pupa (B) the antennae, mouth parts, and legs of the mosquito are still attached in the pupal exuvia. (C) Emergence of adults from pupa (D) Intermediate stage between adult and pupa (E) Generation of pupa from larvae (F) Intermediate stage between larva and pupa.

(A) Larvicidal activity of the acetone extract of Lantana camara against Cx. Pipiens. The different concentrations of the extract were used to assess the larval mortality, rate of pupa production, rate of emergence, and rate of inhibition. (B) Different concentrations of extracts of Rhazya stricta was assessed against Cx. Pipiens estimate it’s larvicidal activity. The assessment was carried out to determine the larval mortality, rate of pupa production, rate of emergence, and rate of inhibition. Different concentrations of azadirachtin were used as positive control.

Previous studies reported very strong larvicidal activities of acetone, ethanolic and methanolic extracts of the L. camara against Anopheles stephensi, Aedes aegypti and Cx. quinquefasciatus, larvae (Abutaha et al., 2018a). The larvicidal activity of L. camara was evaluated in previous studies and the results revealed a very high level of insecticidal activities against mosquitos (Fatope et al., 2002). The methanol and ethanol extract were prepared and their larvicidal activity was observed against Cx. pipiens and Aedes aegypti. The extracts exhibited a profound larvicidal activity.

The R. stricta plant extract was also used to determine the larvicidal activity against the Cx. pipiens. The percentage of larvae mortality was 6, and 71% when 100 and 1000 mg/l of the extract R. stricta was applied respectively. Similarly, only 9 pupae out of 29 were transformed in to adults, showed 91% inhibition at the concentration of 1000 mg/l (Fig. 2B). Commercially available larvicidal chemical azadirachtin was used as a positive control.

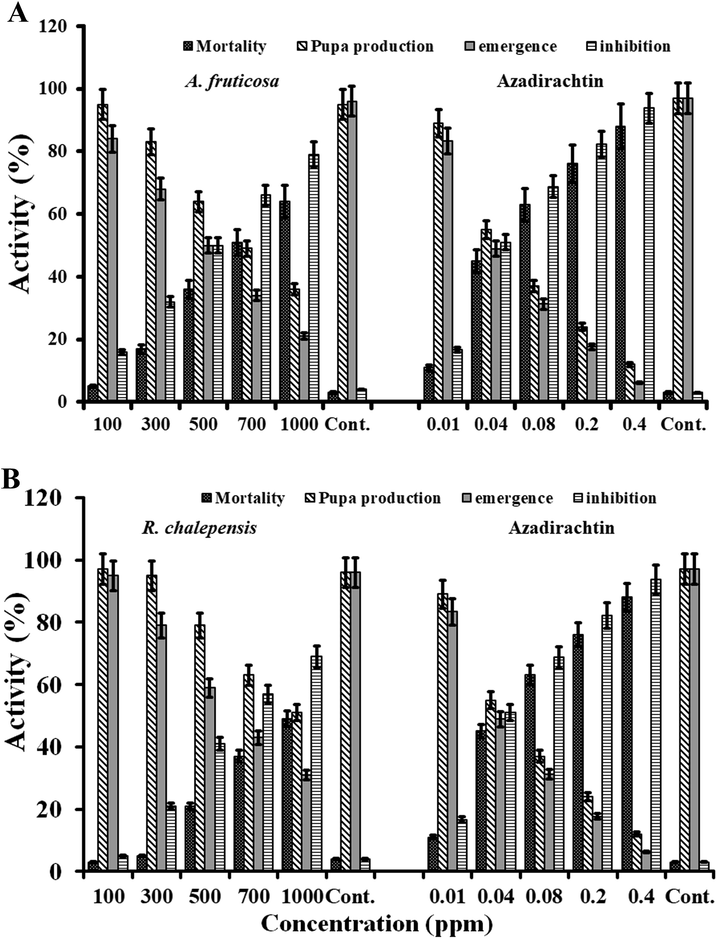

The rate of larval mortality of A. fruticosa extract was 5 and 64% at 100 and at 1000 mg/l respectively. Moreover, at the concentration of 1000 mg/ml, 21 out of 36 larvae were transformed in to adults and the percent inhibition at 100 and 1000 mg/l was 16 and 79% respectively (Fig. 3A). Commercially available larvicidal chemical azadirachtin was used as a positive control. The chloroform extracts of the leaves of A. fruticosa showed the best activity against the cabbage moth. The leaves were found to have terpenoids, saponins, and other pesticidal compounds. Previous study showed the potential of leaf extracts of Acalypha indica against Anopheles stephensi (Lingathurai et al., 2011).

(A) Larval mortality, rate of pupa production, rate of emergence, and rate of inhibition of Cx. Pipiens were determined after treatment of the extract (different concentrations) of Acalypha fruticose. (B) Toxicity of the extract of Ruta chalepensis was determined against larvae of Cx. Pipiens. the larval mortality, rate of pupa production, rate of emergence, and rate of inhibition were assessed after treatment of different concentrations of the extract. Azadirachtin were used as positive control in different concentrations.

The rate of mortality of larvae after the application of 1000 mg/l of the extract of R. chalepensis was 49%. The number of adults emerging from the surviving pupae were decreased and percent inhibition at the concentration of 1000 mg/l was increase up to 69% (Fig. 3B). Commercially available larvicidal chemical azadirachtin was used as a positive control. The studies focused on Ae. albopictus (Conti et al., 2013), Ae. Aegypti (Ali et al., 2013), Cx. pipiens and barber’s pole worm (Brugman et al., 2018).

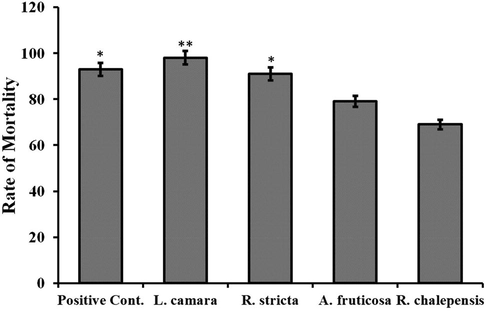

The overall results revealed that the extract of L. camara caused 98% larval mortality showing a significantly higher rate of mortality as compared to activities of all the other plant extracts (Fig. 4). Initial studies indicated that the leaves of L. camara is a rich source of bioactive molecules (Fatope et al., 2020). In addition, the larvicidal activity of the L. camara was even slightly higher than the azadirachtin used as a positive control. The extract of R. stricta caused 91%, A. fruticosa and R. chalepensis caused 79% and 69% mortality in mosquito larvae respectively. Previous reports also revealed that L. camara was successfully used against insects and caused 100% morality even after 24 h (Keziah et al., 2015). However, the extract of Nepeta cataria showed 70% mortality as compared to L. camara when used against insects in equal concentration and the mortality of S. oryzae was up to 74% (Xu et al., 2016).

A comparison of larvicidal activities caused by different plant extracts against Cx. Pipiens.

3.2 Estimation of lethal concentrations of different plant extracts

The value of lethal concentration (LD50 and LC90) of a chemical means an amount needed to kill 50% and 90% of the members of a tested population respectively. In the present study, the extract of L. camara was evaluated and the results revealed that (Table 1) the LC50 for the plant extract was found to be 264 mg/l and the LC90 was 844.8 mg/l. The Chi value calculated was 8.178. Similarly, the LC50 and LC90 for R. stricta were 293.4 and 1294 mg/l, respectively (Table 1). The value of the calculated Chi was 6.1123. The LC50 and LC90 of the extract of A. fruticosa were 435.6 and 2167 mg/l, respectively (Table 1). The value of calculated Chi was 4.9. The LC50 and LC90 of the leaf extract of R. chalepensis were 611.9 and 2284 mg/l, respectively (Table 1). The value of calculated Chi was 1.3368. The LC50 dose of O. basilicum was applied against the A. stephensi larvae different stages with mortalities ranged from 0.276% to 0.305%, (Dris et al., 2017). The toxic effect of plants e.g., Cymbopogan citrates Acorus calamus, Ocimum basilicum, Mentha arvensis, and Saussurea lappa were assessed against larvae of Cx. quinquefasciatus and Ae. Aegypti, the results revealed the highest larvicidal activity in the volatile oil of O. basilicum with LC50 of 75.35 and 92.30 mg/l respectively (Enan, 2005). The overall larvicidal activity of extract of L. camara was higher as compared to azadirachtin (commercially available larvicidal chemical), used as a reference, and positive control and was also higher than the R. stricta, A. fruticosa, and R. chalepensis. Based on our results and results of the other studies enticed us to investigate the chemical composition of L. camara through (GC–MS).

Plant/ Pesticide

LC50 (ppm)

LC90 (ppm)

Slope

Chi

Conc.

Lower Limit

Upper Limit

Calculated

Tabulated

Lantana camara

264

168.9

352.3

844.8

2.537

8.178

7.8

Rhazya stricta

293.4

248.7

338.6

1294

1.988

6.1123

7.8

Acalypha fruticosa

435.6

374.4

506.3

2167

1.834

4.9543

7.8

Ruta chalepensis

611.9

539.3

705.5

2284

2.240

1.3368

7.8

Azadirachtin

0.044

0.0359

0.0536

0.294

1.558

1.2958

7.8

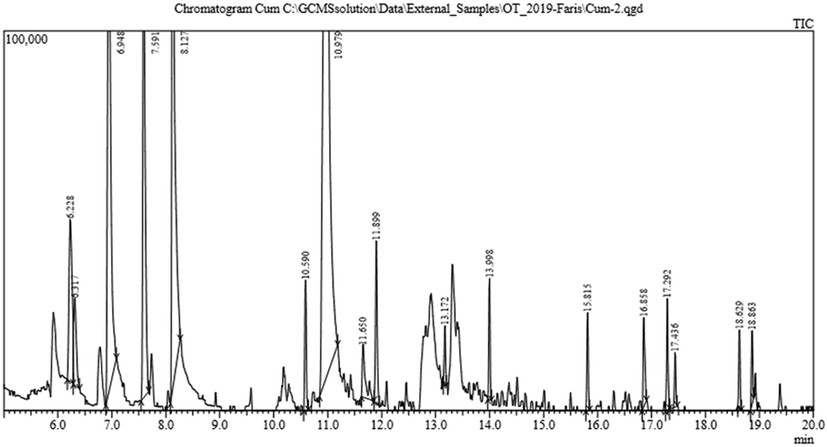

3.3 Assessment of chemical insecticidal compounds of L. Camara through GC–MS

The extract of L. camara showed the highest insecticidal activity against Cx. pipiens as compared to other plant extracts e.g., R. stricta, A. fruticosa, and R. chalepensis used in this study. Therefore, L. camara was subjected to GC–MS analysis to determine the chemical constituents of the extract of L. camara. The GC–MS profile of the compounds showed some very important biological active metabolites that have been reported with very strong insecticidal activities (Fig. 5). A wide array of a chemical compound of L. Camara has been reported, which showed the importance of the plant extracts (Table 2). The wide array of the metabolites can be attributed to the influence of gene pool which is translated into a variety of metabolites against a wide range of insects (Khan et al., 2017; Ullah et al., 2020). RT, retention time; A/H, ration of area and hight.

GC–MS spectra of the extract of Lantana camara shows the peaks of different compounds.

Peak#

RT

Area

Height

A/H

Name

1

6.228

171,231

42,738

4.01

Undecane, 3,7-dimethyl-

2

6.317

73,832

22,839

3.23

3-Nonen-1-ol, (Z)-

3

6.948

531,544

123,380

4.31

4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-

4

7.591

397,235

143,486

2.77

Naphthalene

5

8.127

629,514

163,043

3.86

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural

6

10.59

66,344

34,354

1.93

Hexane, 3,3-dimethyl-

7

10.979

1,330,639

176,843

7.52

Sucrose

8

11.65

54,738

13,431

4.08

Butyl(dimethyl)silyloxycyclopentane

9

11.899

90,674

42,854

2.12

Tetrasiloxane, 3,5-diethoxy-1,1,1,7,7,7-hexamethyl-3,5-bis(trimethylsiloxy)-

10

13.172

26,305

15,605

1.69

Hexane, 3,3-dimethyl-

11

13.998

52,812

31,936

1.65

N-(Trifluoroacetyl)-N,O,O',O''-tetrakis(trimethylsilyl)norepinephrine

12

15.815

44,140

25,810

1.71

Cyclohexasiloxane, dodecamethyl-

13

16.858

54,228

23,471

2.31

Methyl valerate

14

17.292

51,583

29,348

1.76

1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-methylpropyl) ester

15

17.436

22,593

14,381

1.57

1-(2-Methoxyethoxy)-2-methyl-2-propanol, methyl ether

The compounds such as Cyclopentasiloxane were found in Cornus officinalis, where 5-hydroxymethyl furfural was the most important metabolite, showed significant insecticidal activity against mosquito which showed strong larvicidal agent against different insects including mosquitos (Ullah, 2019). Ullah et al. (2015) detected secondary metabolites i.e., benzylideneacetone, acetylated phenylalanine-glycine-valine indole, proline-tyrosine, oxindole, p- and hydroxyphenyl propionic acid which showed very strong insecticidal activities against different insects such as Plutella xylostella, Manduca sexta, Salix exigua. Naphthalene was also detected in the extract of L. camara in the present study which has been used as an insecticidal compound. Tineola bisselliella and Tinea pellionella demonstrated that Naphthalene showed insecticidal activity against a wide range of insects such as moth, mosquitos, and other insects (Supriya et al., 2010).

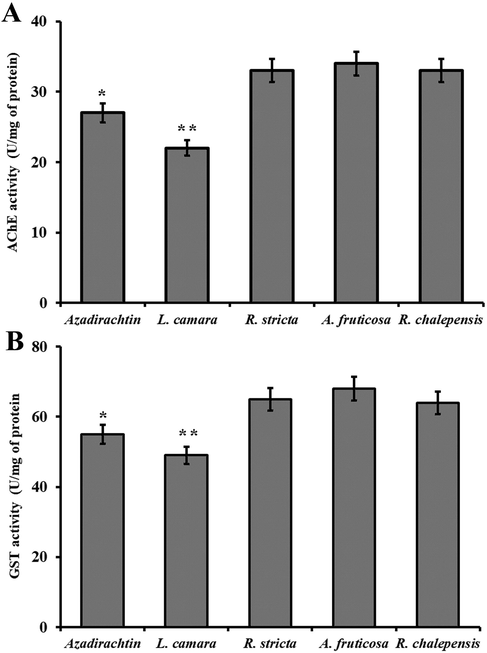

3.4 Assessment of AChE activity in larvae

The activity of AChE was determined in the larvae of Cx. pipiens treated at the concentration of 1000 mg/l of the extract of L. camara. The results (Fig. 6A) showed that the extract significantly (P < 0.05) inhibited the specific activity of AChE in larvae as compared to the other plant extract as well as azadirachtin, used as a positive control. Results showed that the extract of L. camara significantly restricted the AchE activity in larvae as compared to the larvae treated with other plant extract and/or positive control. Due to these results it has been suggested that the extract of L. camara significantly reduced the production of antioxidants as compared to other plant extracts which might be the reason to cause a higher rate of mortality in mosquitos (Abutaha et al., 2018; Rehman et al., 2020).

Assessment of antioxidant enzymes in larvae. (A) Analysis of AChE in the larvae of Cx. Pipiens treated with different plant extract. (B) Analysis of GST in the larvae of Cx. Pipiens treated with different plant extract. The (*) represents positive control and (**) represents significant difference from control.

Chemicals including camphor and fenchone have been reported as AChE inhibitors in several insects such as Tribolium castaneum and Sitophilus oryzae (Farnesi et al., 2012). GC–MS profiling revealed the presence of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, naphthalene, Cyclopentasiloxane, benzene dicarboxylic acid, tridecanoic acid. Most of these chemicals have been reported as a strong pesticide. These compounds inhibit the AChE, which is used to protect the insects against the insecticidal compounds, and hence the extract was highly toxic to the insects due to these metabolites.

3.5 Analysis of the GST activity in larvae

The GST activity was measured in larvae treated with different plant extracts and results revealed that the GST activity was significantly reduced in larvae treated with extract of L. camara as compared to other plans extract as well as a positive control (Fig. 6B). The GST has been reported to play an important role in stress physiology and are implicated in intracellular transport and various biosynthetic pathways (Rehman and Rather, 2019). The extract of L. camara showed the most significant larvicidal effects because it was succeeded to reduce the GST level and hence the immune level of the larvae was overcome by the toxicity of L. camara earlier as compared to other plants (Gülçin et al., 2016b; Gulçin et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2020).

4 Conclusion

To sum up, all the plants included in the study showed an appreciable larvicidal activity and the highest activity was exhibited by L. camara. The study further necessitates the complete phytochemical analysis of the leaf extracts. The extract of L. camara significantly reduced the activities of AChE and GST enzymes in larvae as compared to other plant extract. The phytochemical analysis will indicate clearly that what compounds present in the leaves bear larvicidal activity. Furthermore, the toxic effect of the plants on animals should also be checked, only then they can be deemed safe for human use.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant No. (J: 211-130-1440). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Larvicidal potency of selected xerophytic plant extracts on Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) Entomol. Res.. 2018;48:362-371.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: A green expertise. J. Adv. Res.. 2016;7(1):17-28.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biting deterrence, repellency, and larvicidal activity of Ruta chalepensis (Sapindales: Rutaceae) essential oil and its major individual constituents against mosquitoes. J. Med. Entomol.. 2013;50:1267-1274.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aras, A., Bursal, E., Türkan, F., Tohma, H., Kılıç, Ö., Gülçin, İ., Köksal, E., 2019. Phytochemical Content, Antidiabetic, Anticholinergic, and Antioxidant Activities of Endemic Lecokia cretica Extracts. Chem Biodivers 16, e1900341, doi:10.1002/cbdv.201900341.

- A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem.. 1976;72(1-2):248-254.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brugman, V., Hernández-Triana, L., Medlock, J., Fooks, A., Carpenter, S., Johnson, N.J.I.j., 2018. The role of culex pipiens L.(diptera: culicidae) in virus transmission in Europe. Int. J Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 389-394. https://doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020389.

- Cakmak, K.C., Gülçin, İ., 2019. Anticholinergic and antioxidant activities of usnic acid-an activity-structure insight. Toxicol. Rep. 6, 1273-1280, doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.11.003.

- Larvicidal and repellent activity of essential oils from wild and cultivated Ruta chalepensis L. (Rutaceae) against Aedes albopictus Skuse (Diptera: Culicidae), an arbovirus vector. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(3):991-999.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and activity of an Ocimum basilicum essential oil on Culex pipiens larvae: Toxicological, biometrical and biochemical aspects. S. Afr. J. Bot.. 2017;113:362-369.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity and GC–MS analysis of Leucas aspera against Aedes aegypti Anopheles stephensi and Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Saudi Soc. Agricul. Sci.. 2017;16(4):306-313.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol.. 1961;7(2):88-95.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular and pharmacological analysis of an octopamine receptor from American cockroach and fruit fly in response to plant essential. Arch. Insect. Biochem. Physiol.. 2005;59:161-171.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Farnesi, L.C., Brito, J.M., Linss, J.G., Pelajo-Machado, M., Valle, D., Rezende, G.L., 2012. Physiological and morphological aspects of Aedes aegypti developing larvae: effects of the chitin synthesis inhibitor novaluron. PLoS One 7, e30363-e30363. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030363.

- Larvicidal Activity of Extracts and Triterpenoids from Lantana camara. Pharm. Biol.. 2002;40(8):564-567.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anticholinergic, antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of Anatolian pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium)-analysis of its polyphenol contents by LC-MS/MS. Biocatal. Agricult. Biotechnol.. 2020;23:101441.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) on metabolic enzymes including acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase, glutathione S-transferase, lactoperoxidase, and carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes I, II, IX, and XII. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.. 2016;31(6):1095-1101.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gülçin, İ., Scozzafava, A., Supuran, C. T., Koksal, Z., Turkan, F., Çetinkaya, S., Bingöl, Z., Huyut, Z., Alwasel, S. H., 2016b. Rosmarinic acid inhibits some metabolic enzymes including glutathione S-transferase, lactoperoxidase, acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase and carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 31, 1698-702, doi:10.3109/14756366.2015.1135914.

- Antidiabetic and antiparasitic potentials: Inhibition effects of some natural antioxidant compounds on α-glycosidase, α-amylase and human glutathione S-transferase enzymes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2018;119:741-746.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of nitrogen, phosphorus, selenium and sulfur-containing heterocyclic compounds – Determination of their carbonic anhydrase, acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase and α-glycosidase inhibition properties. Bioorg. Chem.. 2020;103:104171.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Günaydin a, K., Savci b, S.J.N.P.R., 2005. Phytochemical studies on Ruta chalepensİs (LAM) lamarck. Natural Prod. Res. 19, 203-210. Doi: 10.1080/14786410310001630546.

- Cloning and expression of the insecticidal toxin gene “tccB” from Photorhabdus temperata M1021 in Escherichia coli expression system. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol.. 2020;23(1):172-176.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Keziah, E.A., Nukenine, E.N., Danga, S.P.Y., Younoussa, L., Esimone, C.O., 2015. Creams formulated with Ocimum gratissimum L. and Lantana camara L. crude extracts and fractions as mosquito repellents against Aedes aegypti L. (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Insect. Sci. 15, 45-50. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iev025.

- Host plant growth promotion and cadmium detoxification in Solanum nigrum, mediated by endophytic fungi. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2017;136:180-188.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A., Jahan, S., Imtiyaz, Z., Alshahrani, S., Antar Makeen, H., Mohammed Alshehri, B., Kumar, A., Arafah, A., Rehman, M. U., 2020. Neuroprotection: Targeting Multiple Pathways by Naturally Occurring Phytochemicals. Biomedicines 8, doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8080284.

- Antifeedant and larvicidal activities of Acalypha fruticosa Forssk. (Euphorbiaceae) against Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) larvae. J. King Saud University – Sci.. 2011;23(1):11-16.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity of Leucas aspera (Willd.) against the larvae of Culex quinquefasciatus Say. and Aedes aegypti L. J. Saudi Soc.. 2008;2:214-217.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, M. U., Rashid, S., Arafah, A., Qamar, W., Alsaffar, R. M., Ahmad, A., Almatroudi, N. M., Alqahtani, S. M. A., Rashid, S. M., Ahmad, S. B., 2020. Piperine Regulates Nrf-2/Keap-1 Signalling and Exhibits Anticancer Effect in Experimental Colon Carcinogenesis in Wistar Rats. Biology (Basel) 9, doi: 10.3390/biology9090302.

- Rehman, M. U., Rather, I. A., 2019. Myricetin Abrogates Cisplatin-Induced Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Response, and Goblet Cell Disintegration in Colon of Wistar Rats. Plants (Basel) 9, doi: 10.3390/plants9010028.

- Supriya, B., Patra, P.S., Bisweswar, M., 2010. Efficacy of some vegetable oils and naphthalene in storage condition against Callosobruchus chinensis L. infestation. Int. J. Appl. Agric. Sci. 1, 174-176. https://doi.org/10.37322

- Antioxidant and anticholinergic properties of olivetol. J. Food Biochem.. 2018;42(3):e12516.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Novel eugenol derivatives: Potent acetylcholinesterase and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2017;94:845-851.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Turhan, K., Pektaş, B., Türkan, F., Tuğcu, F. T., Turgut, Z., Taslimi, P., Karaman, H. S., Gulcin, I., 2020. Novel benzo[b]xanthene derivatives: Bismuth(III) triflate-catalyzed one-pot synthesis, characterization, and acetylcholinesterase, glutathione S-transferase, and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory properties. Archiv. der Pharmazie 353, 2000030, Doi: 10.1002/ardp.202000030.

- Türkan, F., Huyut, Z., Taslimi, P., Huyut, M. T., Gülçin, İ., 2020. Investigation of the effects of cephalosporin antibiotics on glutathione S-transferase activity in different tissues of rats in vivo conditions in order to drug development research. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 43, 423-428, doi:10.1080/01480545.2018.1497644.

- Ullah, I., 2019. Improvement of Cadmium Detoxification Potential and Plant Growth Promotion by Bacterial Endophytes. Preprints.org.

- Ullah, I., Al-Ghamdi, K. M. S., Anwar, Y., A. Mahyoub, J., 2020. Exploring the Insect Control and Plant Growth Promotion Potentials of Endophytes Isolated From Calotropis procera Present in Jeddah KSA. Natl. Prod. Commun. 15, 1934578X20912869, doi:10.1177/1934578x20912869.

- Benzaldehyde as an insecticidal, antimicrobial, and antioxidant compound produced by Photorhabdus temperata M1021. J. Microbiol.. 2015;53(2):127-133.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A Novel Insecticidal Peptide SLP1 Produced by Streptomyces laindensis H008 against Lipaphis erysimi. Molecules. 2016;21:1101-1109.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal Activity of Medicinal Plant Extracts Against Aedes aegypti, Ochlerotatus togoi, and Culex pipiens pallens (Diptera: Culicidae) J. Asia-Pac. Entomol.. 2004;7(2):227-232.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]