Translate this page into:

Laboratory evaluation of the effects of Portunus pelagicus extracts against Culex pipiens larvae and aquatic non-target organisms

⁎Correspondent author. falmekhlafi@ksu.edu.sa (Fahd A. Al-Mekhlafi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) is a pathogen-bearing mosquito found worldwide. Marine organisms are a promising source to search for mosquito-killing substances. The potential of the different solvent extracts of Portunus pelagicus was examined using Cx. pipiens 3rd instar. The bio-safety evaluation was carried out using Danio rerio (zebrafish) and Artemia nauplii (brine shrimp). The larvicidal activity of Portunus pelagicus (blue crab) was found in chloroform extracts against Cx. pipiens 3rd instars, with LC50 value of 109.11 and LC90 value of 88.44 ppm after 48 h of treatment. A Biosafety assessment of P. pelagicus methanol extract on D. rerio and A. nauplii revealed that the extract had toxic effects on A. nauplii but was safe for D. rerio. However, the non-toxicity of the extract towards D. rerio may be misleading; further investigation on other aquatic organisms is required. Thus, the extract should be used with caution.

Keywords

Culex pipiens

Toxicity

Larvicidal property

Portunus pelagicus

Zebrafish

1 Introduction

Marine natural products are unexplored sources of promising compounds of multipurpose applications that have drawn the attention of scientists for the discovery of innovative medications. (Rekha et al., 2018). Many marine organisms are exposed to extreme environmental conditions that permit them to adapt to new environments and produce different secondary metabolites not found in other organisms (Rekha et al., 2018). Several researchers have reported that secondary metabolites extracted or isolated from marine invertebrates possess biological and therapeutic activities such as anti-parasitic, anticancer, antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities (Barzkar et al., 2019). Marine crabs possess active compounds isolated from different tissues and organs, such as chitin (Casadidio et al., 2019), glucosamine (Barrow, 2010), astaxanthin, and phenolic compounds (Rasmussen and Morrissey, 2007).

Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) is distributed far and wide and may transmit many pathogens, such as the filarial parasite, Rift Valley fever virus, and West Nile virus to humans and animals (Kasai et al., 2008). Cx. pipiens can be found in several Saudi Arabian provinces (Alahmed et al., 2019) and was the most promising vector of bancroftian filariasis (Omar, 1996), reported to be resistant to many insecticides deltamethrin, cyfluthrin, bifenthrin, and this resistance is increasing (Al-Sarar, 2010).

Mosquito control is mainly dependent on synthetic insecticides. Insecticides eliminate large numbers of mosquitoes; as a result, it reduces the transmission of disease but causes resistance in mosquitoes, which may spread to mosquitoes from different geographic regions (Demok et al., 2019; Organization, 2018).

Mosquitocide resistance in Cx. pipiens has been reported from different areas in Riyadh (Al-Sarar et al., 2005). It has been revealed to have marked resistance to deltamethrin (187.1 folds), Moderate to low resistance to beta cyfluthrin (14 folds), and lambda cyhalothrin (3.8 folds) respectively (Al-Sarar, 2010). Cx. pipiens isolated from other countries have also shown high resistance levels to deltamethrin (233– and 453-folds) (Daaboub et al., 2008), moderate and low resistance levels to bifenthrin (38.4-fold), and lambda-cyhalothrin (3.8-fold) (Nazni et al., 2005). However, Cx. pipiens was reported to be susceptible to fenitrothion (Al-Sarar, 2010).

Natural products are increasingly used to combat vectors because they are considered safe to use, such as Azadirachta indica, Anacadium occidentale, Mangifera indica and Cocos nucifera (Innocent et al., 2014). These natural products, however, can have a detrimental effect on the non-target organisms. If a natural product extract is to be used for controlling mosquito larvae, there is a possibility that some components may leak into the groundwater and migrate into nearby rivers and streams, causing toxicity to non-target organisms (Cannon et al., 2004).

There is a large body of literature on the biosafety assessment of natural products on non-target organisms such as D. rerio and Artemia nauplii (Abutaha et al., 2020; Ragavendran et al., 2019). Interesting similarities exist between the genetic make-up of humans and D. rerio, including the presence of over 84% of the genes associated with human illnesses. (Truong et al., 2014). A. salina is a valuable test organism used for toxicity testing with several toxicology applications (Nunes et al., 2006). This is because A. salina assays could replace cytotoxicity assays that contain animal serum (McLaughlin et al., 1998). The cytotoxicity assays are expensive, time-consuming, tedious, and lack simplicity. Currently, A. salina tests are used in toxicology (Costa-Lotufo et al., 2005) to screen extracts for drug discovery (Sangian et al., 2013).

Therefore, the effects of natural product extracts on non-target aquatic organisms must be studied in detail before they are recommended for mosquito control programs. The effects of P. pelagicus extract on mosquitoes and non-target aquatic species have not been documented.

2 Material and method

2.1 Preparation of solvent extracts

Portunus pelagicus was purchased from the market, washed several times with distilled water (DW), and then oven dried at 50 °C for 72 h. After being pulverized in an electronic blender, 80 g of the substance was extracted using the Soxhlet method in a series of four different solvents: hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and methanol. All the extracts obtained were filtered. The solvents were evaporated separately using a rotovap (Germany). The dried extract from each solvent extract was then dissolved in methanol to obtain two fractions. One of the fractions is methanol-soluble, whereas the other is not (soluble only in hexane). The fractions were evaporated. All the fractions were kept at − 80 °C in glass bottles until use. Stock solutions (100 mg/mL) of methanol soluble fraction were then subjected to larvicidal screening. The insoluble methanol fractions were untested due to their insolubility in water.

2.2 Preparation of aqueous extracts

Portunus pelagicus (70 g) was soaked in 500 mL of DW, sonicated for 30 min, and kept on a shaker for 3 h. Later, the extract was filtered, evaporated using rotovap, and kept at − 80 °C in glass bottles until use. Stock solutions (10 mg/mL) were made after being stored for 24 h, and larvicidal screening was carried out.

2.3 Larva rearing

Eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults of Cx. pipiens were collected from the insectary at Zoology Department (King Saud University, Saudi Arabia, Riyadh) at 28 ± 2 °C and under a 12-h photoperiod.

2.4 Mosquito larvicidal bioassay

The recent larvicidal activity of P. pelagicus extracts (133–233 ppm) was calculated after 24 and 48 h. Portunus pelagicus extracts were individually introduced to sterile six-well plates (Corning Inc., NY, USA), allowed to evaporate, and redissolved in tap water (total volume, 6 mL) to test against the 3rd instar Cx. pipiens. The assay was done in triplicate with 20 larvae per concentration. Aqueous control and methanol (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) control were maintained separately. During the treatment, the larvae were fed TetraMint ground fish meal (Germany). Larval mortality (%) was calculated 24 and 48 h post-treatment and expressed as 50% (LC50) and 90% (LD90) lethal dose values. Probit analysis was used to calculate the LC50 and LC90 (Finney, 1952).

2.5 Histopathology study

For histological investigations, larvae (treated and control) were fixed in buffered formalin (10%), then processed as reported previously (Al-Doaiss et al., 2021) using an automatic tissue processor (Sakura, Finetek, Japan), embedding station (Sakura) and a rotary microtome (RM2245, Leica Biosystems, Wetzler, Germany). Finally, the sections (5 μm) were stained (hematoxylin and eosin) using an autostainer (5020, Leica Biosystems). The stained sections were photographed using a microscope (BX53, Olympus, Japan).

2.6 Non-targeted organism test

2.6.1 Artemia nauplii

Artemia cysts (BIO-MARINE®, USA) were hatched following the method of Latha et al. (2016). A. nauplii eggs (50 mg) were added to 1000 mL seawater (salinity of 30 parts per thousand) in a separatory funnel under 26 ± 2 °C, pH 8.4; and light: dark period of 16:8h. The flask was aerated for 24 h using an air pump. The hatched A. nauplii (24 h) were used for toxicity tests using 500, 375, 175,100, and 50 µg/ml of chloroform extract. Freshly hatched eggs were separated into six sets (groups), each containing 50 animals. Seawater was used as a control. The assay was carried out in six-well plates using 3 mL seawater for 24 h to evaluate the toxic effect of P. pelagicus extract. The mortality was reported after 24 h, and the experiment was replicated thrice. The LD50 value was calculated using the origin software.

2.6.2 Toxicity on Danio rerio

Wild-type AB strain D. rerio (1 year) were acquired from the International Resource Center, Oregon University, USA, and kept in fish tanks (10-liter tanks; Tecniplast, Exton, PA, USA) at 28.5 °C and pH 7.5 and fed daily with Zeigler flake food (Zeiglers Bros, USA). Danio rerio were used for the non-target organism test, with three fish (three replicates) being tested with 180 and 220 μg/mL extract dissolved in 400 mL of fish water. A control group was also established with 400 mL of fish water. The tests were performed for 24 h, and fish mortality was recorded.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The LC50 and LC90% confidence limits and chi-square values of mortality were calculated using probit analysis using SPSS software. All the results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3 Result

The various extraction solvents were found to have significant weight differences in the yield obtained. The lowest percentage yield was found in ethyl acetate (10 mg), hexane (20 mg), and chloroform (1 g) extract, respectively. In contrast, the highest yield was observed in the methanol (12 g) and aqueous (10 g) extracts.

The mortality in the percentage of Cx. pipiens larvae post-treatment with different P. pelagicus chloroform extracts concentrations is given in Table 1. The promising result were found against the 3rd instar Cx. pipiens using the chloroform extract, resulting in LC50 values of 180.05 µg/mL after 24 h of treatment (Table 1). The LC50 value was 109.11 after 48 h of treatment with the chloroform extract. In control (methanol), all the larvae were live, and no mortality was reported. However, in the treatment group, the dead larvae settled down. The analysis revealed that LC50 and LC90 values decreased gradually with time. Dose-dependent mortality was also correlated positively with extract concentrations (Table 1). LC50 - lethal concentration 50% mortality, LC90 - lethal concentration 90% mortality. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was used to assess significant differences between the recorded readings (three replicates of 20 each). Data for columns with different letters are significantly different P < 0.05.

Concentration (μg/mL)

% Mortality ± SE

Time

24 h

48 h

133

00 ± 00d

26.67 ± 3.33c

167

33.33 ± 3.33c

56.67 ± 3.33b

200

80.00 ± 5.77b

100 ± 0.00a

233

100.00 ± 0.00a

0.00a ± 100

Control

00 ± 00d

6.67 ± 3.33d

LC50 (μg/mL)

180.05

88.44

LC90 (μg/mL)

218.47

109.11

Df

4

4

F-value

236.50

268.00

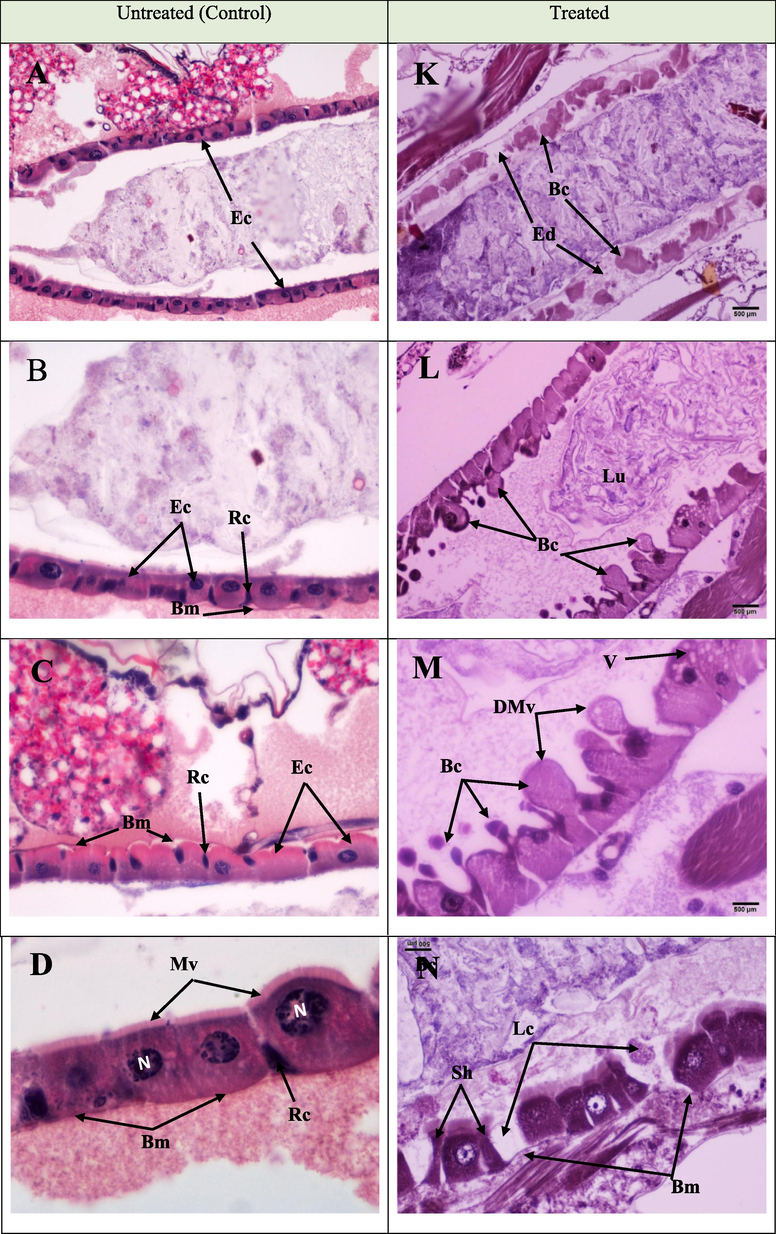

In the control group, the midgut was lined by a simple cuboidal epithelial broad healthy cell with rounded large nuclei, smooth acidophilic cytoplasm, and well-developed microvilli (brush border). All epithelial cells were closely attached to the basement membrane (basal lamina). A peritrophic membrane-surrounded lumen shields the epithelia from food substances (Fig. 1A–D). In contrast, the histopathological observation of the midgut of the treated larvae exhibited aberrations (Fig. 1. K–N) such as severe damage, structural disorganization, deformation, and maximum degeneration of epithelial cells (De) and edema (Fig. 1[K]). Formation of globular protrusions towards the lumen and epithelial cell blebbing into the gut lumen were observed (Fig. 1[L]). Swelling or elongation and blebbing of the epithelial cells, degradation and destruction of microvilli, and vesicle formation in the cytoplasm of the epithelial cell were also observed (Fig. 1[M]). Moreover, the treated larvae exhibited alterations in cell size and shape (Fig. 1[N]).

The longitudinal section in the midgut of Culex pipiens larvae showing histopathological alterations induced by Portunus pelagicus on the epithelia of the midgut of Cx. pipiens larvae. A to D represent longitudinal sections in the midguts of untreated control larvae, showing typical and healthy epithelial cells (Ec), microvilli (Mv), nuclei (N), and regenerative cells (Rc). K to N represent longitudinal sections in midguts of treated larvae, showing affected gut epithelial layer with several lesions. Degenerated epithelial cells (De), edema (Ed), blebbing (Bc), protruding cells into the lumen (Lu), degraded microvilli (DMV), swelling or elongation, and blebbing of the epithelial cells, alterations in cell size and shape of epithelial cells (Sh), irregular basement membrane (Bm), and loss of some cells (Lc).

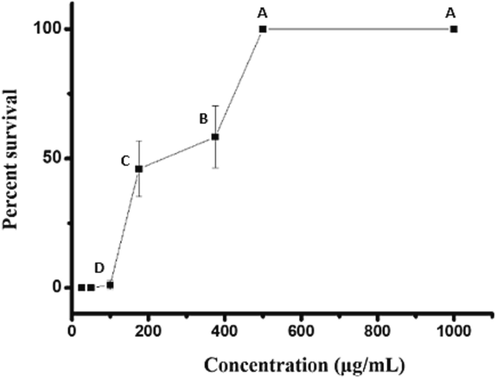

The toxicity of P. pelagicus chloroform extract on A. nauplii after 24 h od exposure is presented in Fig. 2. The control and the 500, 375, 175, 100, and 50 ppm treated groups showed 0, 100, 58, 45, and 1% mortality after 24 h treatment, respectively. However, the calculated LD50 value was 242 µg/mL. Based on the result obtained, P. pelagicus chloroform extract was unsafe for A. nauplii at high concentrations; the LC50 of the extract for A. nauplii is higher than that for mosquito larvae. The effect of P. pelagicus chloroform extract against a non-target organism, D. rerio, is shown in Fig. 3. Results indicated that the extract is not toxic to D. rerio at LC50 (250 µg/ml) and LC100 (500 µg/ml) doses.

Toxicity of Portunus pelagicus chloroform extract against Artemia nauplii.

Testing the toxicity of Portunus pelagicus chloroform extract on Danio rerio.

4 Discussion

Researchers worldwide are interested in finding natural mosquitocidal chemicals that are environmentally safe, and it is preferred for mosquito control more than synthetic mosquitocides (Benelli et al., 2015). Nature is rich in novel bioactive compounds for the welfare of humankind. The literature reveals that the products extracted from marine habitats have more novel bioactive compounds with higher biological activities than those isolated from terrestrial sources (Sujatha and Joseph, 2011). Recently, extracts from marine organisms have been screened for larvicidal activity. Few investigations have described the application of products from marine organisms such as sea squirt (Chio and Yang, 2008; Mohd Hussein et al., 2001), sea lily (Su et al., 2016), and marine sponges (Reegan et al., 2015; Sujatha and Joseph, 2011) as mosquito control agents. Extracts of marine green algae such as Ulva lactuca Linn, Halimeda macroloba Decsne, and Caulerpa racemosa Frosk have also been investigated for their insecticidal activity (Adaikala Raj et al., 2017). However, to our knowledge, no researcher has studied the mosquitocidal potential of P. pelagicus extracts.

Histomorphological changes in larvae treated with 90 μg/mL extract indicate the larval death cause. Anatomically, the midgut of Cx. Pipiens larvae is divided into three regions. All regions are composed of a single cuboidal epithelial cell layer with apical microvilli (Mahmoud et al., 2019). The release of digestive enzymes and nutrient absorption via the microvilli are essential activities of the midgut in larvae (Yu et al., 2015). Most previous studies have shown that larvicidal substances cause damage to the epithelial cells of the midgut, which is probably where the compounds are absorbed. The injury to the midgut region disrupts its function, causing larval death (Jiraungkoorskul and Jiraungkoorskul, 2015). Histopathological alterations observed in the midgut include edema, protruding cells, microvilli (brush border) destruction swelling or elongation, and blebbing of the epithelial cells, and vacuolization of cytoplasm, and alterations in cell size and epithelial cell shape. These observations agree with the findings of previous studies (Yu et al., 2015) (Abutaha et al., 2022) (Almkehlafi et al., 2018). (Mahmoud et al., 2019) recorded histopathological results and toxicological data in the midgut region of larvae treated by plant extracts (Piper nigrum, Azadirachta indica, and Eucalyptus regnans) and showed that the alterations were epithelial cell vacuolization, microvilli disorganization, and basement membrane detachment. Similarly, Cx. pipiens treatment with Artemisia judaica resulted in cell swelling, epithelial cell vacuolation, the appearance of cell debris in the lumen, and loss of normal features of the midgut (Hamouda et al., 1996). Most histological alterations on Cx. quinquefasciatus were microvilli destruction, swelling, protruding, degeneration, and epithelial cell vacuolization after treatment with Melia azedarach or Matricharia chamomilla extracts (Al-Mehmadi and Al-Khalaf, 2010) (Almehmadi, 2011). Regardless of the type of natural or chemical larvicidal substance used, the similarities in histological changes in the midgut epithelia indicate that such changes are a response to cellular toxicity (Jiraungkoorskul and Jiraungkoorskul, 2015).

Lowering the mucosal membrane's surface tension is a major function of metabolites resulting in damaging the digestive system, therefore ion transport, osmoregulation, and nutrition absorption (Sina and Shukri, 2016).

A promising mosquitocidal extract should be target-specific. Hence, toxicity testing using the A. nauplii is a rapid method to evaluate the toxicity of substances (McLaughlin et al., 1998). Extracts with LC50 values higher than 1000 g/mL are non-toxic, whereas those with LC50 values of 1000 g/ml are considered harmful, according to earlier (Clarkson et al., 2004) toxicity indices. The biotoxicity of chloroform extract was assessed on the non-target organism A. nauplii. According to our findings, the extract was poisonous to A. nauplii, with an LC50 value of 242 g/mL.

The effect of the extract on non-target organisms showed that P. pelagicus chloroform extracts are safe on D. rerio but not on A. nauplii. However, further evaluation is required to assess damages and deformities in tested organisms using different methods and parameters.

This suggests that this extract should be used with caution. The non-toxicity of the extract on D. rerio may be misleading and lead to problems for other aquatic species. However, further research is needed to assess its effects on a wide range of non-target organisms to get the complete picture before being considered an alternative to current mosquitocides.

5 Conclusion

The current work documents the larvicidal actions of P. pelagicus against Cx. pipiens for the first time. The screening results suggest that P. pelagicus chloroform extracts are promising for larval control. However, further investigation is required to isolate the active compound/s in the extract and identify their mechanism of action.

Acknowledgement

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R112), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This project was funded by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R112), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Target and nontarget toxicity of Cassia fistula fruit extract against Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae), lung cells (BEAS-2B) and Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. J. Med. Entomol.. 2020;57(2):493-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of different extracts of marine macro green algae for larvicidal activity against dengue fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti (diptera: Culiadae) International Letters of Natural Sciences. 2017;62:44-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment and an updated list of the mosquitoes of Saudi Arabia. Parasit. Vectors. 2019;12(1):1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological, histological and ultrastructural characterisation of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) larval midgut. African Entomology. 2021;29(1):274-288.

- [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mehmadi, R.M., Al-Khalaf, A.A., 2010. Larvicidal and histological effects of Melia azedarach extract on Culex quinquefasciatus Say larvae (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of King Saud University-Science 22 77-85(2).

- Almehmadi, R.M., 2011. Larvicidal Histopathological and Ultra-structure Studies of Matrichiaria chamomella Extracts Against the Rift Valley Fever Mosquito Culex quinquefascia tus (Culicidaee: Diptera). Journal of Entomology-Academic Journals Inc. 8(1), 63-72.

- Insecticide resistance of Culex pipiens (L.) populations (Diptera: Culicidae) from Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia: Status and overcome. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2010;17(2):95-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Susceptibility of Culex pipiens from different locations in Riyadh City to insecticides used to control mosquitoes in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Pest Control and Environmental Science. 2005;13:79-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Marine nutraceuticals: glucosamine and omega-3 fatty acids: new trends for established ingredients. Agro Food Ind Hi Tech. 2010;21(2):36-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolites from marine microorganisms, micro, and macroalgae: Immense scope for pharmacology. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17(8):464.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mediterranean essential oils as effective weapons against the West Nile vector Culex pipiens and the Echinostoma intermediate host Physella acuta: what happens around? An acute toxicity survey on non-target mayflies. Parasitol. Res.. 2015;114(3):1011-1021.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chitin and chitosans: Characteristics, eco-friendly processes, and applications in cosmetic science. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17(6):369.

- [Google Scholar]

- A bioassay for natural insect repellents. J. Asia Pac. Entomol.. 2008;11(4):225-227.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro antiplasmodial activity of medicinal plants native to or naturalised in South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2004;92(2–3):177-191.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies of the anticancer potential of plants used in Bangladeshi folk medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2005;99(1):21-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Resistance to pyrethroid insecticides in Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) from Tunisia. Acta Trop.. 2008;107(1):30-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insecticide resistance status of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes in Papua New Guinea. Parasit. Vectors. 2019;12(1):1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Probit analysis: a statistical treatment of the sigmoid response curve. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1952.

- Toxicity and histopathological effects of Artemisia judaica and Anagallis arvensis extracts on Culex pipiens larvae. Journal-Egyptian German Society of Zoology. 1996;20:43-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-mosquito plants as an alternative or incremental method for malaria vector control among rural communities of Bagamoyo District. Tanzania. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine. 2014;10(1):1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal and histopathological effects of Cassia siamea leaf extract against Culex quinquefasciatus. Trop. Life Sci. Res.. 2015;26(2):15-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- PCR-based identification of Culex pipiens complex collected in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis.. 2008;61(3):184-191.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, D.M., Abd El-Bar, M.M., Salem, D., Rady, M.H., 2019. Larvicidal potential and ultra-structural changes induced after treatment of Culex pipiens L.(Diptera: Culicidae) larvae with some botanical extracted oils. Synthesis 12, 15-18.

- The use of biological assays to evaluate botanicals. Drug Inf. J.. 1998;32(2):513-524.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insecticidal activity of the methanol extracts of some tunicate species against Aedes aegypti and Anopheles maculatus. Pharm. Biol.. 2001;39(3):213-216.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adult and larval insecticide susceptibility status of Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) mosquitoes in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. Trop. Biomed.. 2005;22(1):63-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of the genus Artemia in ecotoxicity testing. Environ. Pollut.. 2006;144(2):453-462.

- [Google Scholar]

- A survey of bancroftian filariasis among South-East Asian expatriate workers in Saudi Arabia. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1996;1(2):155-160.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W.H., 2018. Global report on insecticide resistance in malaria vectors: 2010–2016. https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241514057/en/.

- Larvicidal, histopathological, antibacterial activity of indigenous fungus Penicillium sp. against Aedes aegypti L and Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) (Diptera: Culicidae) and its acetylcholinesterase inhibition and toxicity assessment of zebrafish (Danio rerio) Front. Microbiol.. 2019;10(427):1-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Marine biotechnology for production of food ingredients. Adv. Food Nutr. Res.. 2007;52:237-292.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal, ovicidal and repellent activities of marine sponge Cliona celata (Grant) extracts against Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae) Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med.. 2015;8(1):29-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Searching for crab-borne antimicrobial peptides: Crustin from Portunus pelagicus triggers biofilm inhibition and immune responses of Artemia salina against GFP tagged Vibrio parahaemolyticus Dahv2. Mol. Immunol.. 2018;101:396-408.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiplasmodial activity of ethanolic extracts of some selected medicinal plants from the northwest of Iran. Parasitol. Res.. 2013;112(11):3697-3701.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activities of extract flower Averrhoa bilimbi L. towards important species mosquito, Anopheles barbirostris (Diptera: Culicidae). International Journal of. Zool. Res.. 2016;12(1):25-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insecticidal activity and insect repellency of four species of sea lily (comatulida: comatulidae) from Taiwan. J. Insect Sci.. 2016;16(1):1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sujatha, S., Joseph, B., 2011. Effect of few marine sponges and its biological activity against Aedes aegypti Linn. Musca domestica (Linnaeus, 1758)(Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of fisheries and Aquatic Science 6(2), 170-177.

- A rapid throughput approach identifies cognitive deficits in adult zebrafish from developmental exposure to polybrominated flame retardants. Neurotoxicology. 2014;43:134-142.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity, inhibition effect on development, histopathological alteration and morphological aberration induced by seaweed extracts in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med.. 2015;8(12):1006-1012.

- [Google Scholar]