Translate this page into:

Isolation, characterization, and predatory activity of nematode-trapping fungus, Arthrobotrys oligospora PSGSS01

⁎Corresponding author. shobana@psgcas.ac.in (Coimbatore Subramanian Shobana)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A research study was undertaken to find a fungus that could effectively trap and kill Meloidogyne spp., which are root-knot nematodes that cause significant crop loss worldwide. Soil samples were collected and processed appropriately for the isolation of nematode-trapping fungi. After a primary screening, a potential nematode-trapping fungus, Arthrobotrys oligospora (Orbilia oligospora) PSGSS01 was selected for further investigation. Its growth was tested under various conditions, including different media types, temperatures, and pH levels. Its predatory activity on Meloidogyne incognita was also assessed in vitro. The fungus exhibited septate double-celled conidiospores, trapping hyphae, and radiating and sparse mycelium. Optimal conditions for growth were found to be at 25 °C and a pH of 4.0 and 5.0 on corn meal agar. The best temperature and pH for conidiospore germination were 25°C − 37°C and 5.0, respectively. The isolate could trap 94% of second-stage juveniles of M. incognita, and 92% juvenile mortality was recorded in 120 h at 28°C. Therefore, the study concluded that the isolate A. oligospora (Orbilia oligospora) PSGSS01 could be used as a biological control agent against root-knot nematodes.

Keywords

Arthrobotrys oligospora

Biological control

Growth characteristics

Meloidogyne incognita

Nematode-trapping

- PPNs

-

Plant parasitic nematodes

- RKNs

-

Root-knot nematodes

- NTF

-

Nematode-trapping fungi

- J2

-

Second-stage juveniles

- CMA

-

Corn meal agar

- PDA

-

Potato dextrose agar

- PCR

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- ITS

-

internal transcribed spacer

- NA

-

Nutrient agar

- PCA

-

Potato carrot agar

- MEA

-

Malt extract agar

- SDA

-

Sabouraud’s dextrose agar

- CDA

-

Czapek-Dox agar

- CYA

-

Czapek’s yeast agar

- RBA

-

Rose Bengal agar (RBA)

- REA

-

Rice extract agar

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Plant parasitic nematodes (PPNs) infect plants by altering the root morphology due to their feeding behaviour or by invading the plant tissue. PPNs cause significant losses ranging from 18–25 % in vegetables, 20–25 % in pulses, and 18–23 % in oil seed crops (Kumar et al., 2020). Among PPNs, the root-knot nematode (RKN), Meloidogyne spp., are the most damaging parasites of plant roots, and they parasitise over 3000 plant species (Sun et al., 2008; Regaieg et al., 2010). Various approaches have been used to control these nematodes, but chemical nematicides are commonly used due to their quick results. However, overuse of these pesticides has led to the development of resistance in nematode populations, affecting non-target organisms and the environment (Duponnois et al., 1995, Chauhan et al., 2002). Therefore, it is crucial to develop biological control agents to protect plant crops.

Nematode-trapping fungi (NTF) are widely found in soil and prey on nematodes as a nutrient source. These fungi develop specific trapping devices, such as adhesive networks, knobs, and constricting rings, to trap and extract nutrients from nematode prey (Nordbring-Hertz et al., 2006). Most NTF can live as both saprophytes and parasites and play a key role in maintaining nematode populations in diverse natural environments. Arthrobotrys oligospora is a major NTF and has been considered a model organism for understanding the interaction between fungi and nematodes. It has been widely studied as a possible biological control agent against plant parasitic nematodes (Singh et al., 2005; Tahseen et al., 2005). This study aims to isolate and characterize, a potential NTF from soil samples and determine its optimal growth conditions as well as its predatory activity to use it as a biocontrol agent against root-knot nematodes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Nematodes for the study

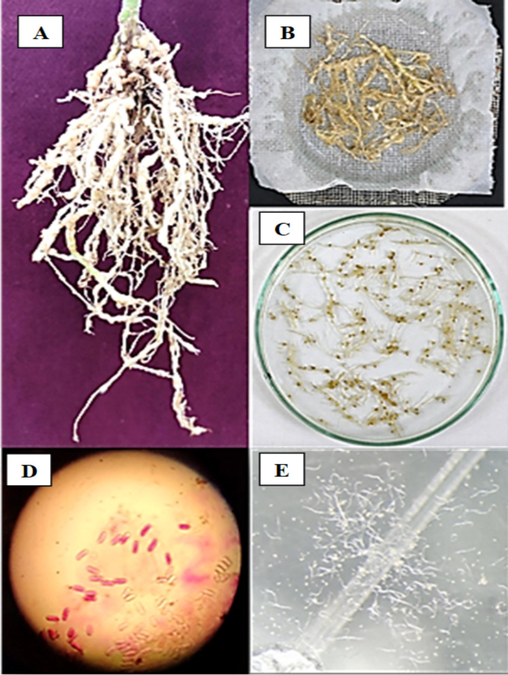

Tomato plants that were infested with nematodes were collected from Thondamuthur Village of Coimbatore district in Tamil Nadu (10.9899° N, 76.8409° E), India. The plants were uprooted, placed in a paper bag, and transported to the laboratory. To extract the nematode eggs, a modified version of Jenkins' method (Jenkins, 1964) was used. The roots were washed with tap water and then washed thrice with sterile distilled water containing chloramphenicol (50 mg/mL). Next, the roots were cut into smaller pieces (10 mm −15 mm) with a sterile scalpel and immersed in sterile distilled water containing chloramphenicol (30 mg/mL) for 30 min. The dislodged and suspended egg masses were transferred into a beaker of sterile water and continuously aerated using a small motor. The hatched nematodes were collected by centrifuging the above at 2000 rpm for 3 min. The harvested second-stage juveniles (J2) were washed three times with sterile distilled water containing tetracycline (50 ppm) (Fig. 1). The nematodes were further confirmed for identification with the Department of Nematology at Tamilnadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore – 641 003, India. J2 larval suspension was allowed to infect tomato cultivar Jyothi in earthen pots containing sterile soil. These plants served as the source of nematodes for subsequent studies.

Root portion of tomato plant infected with Meloidogyne sp. (A); Pieces of infected roots processed for the collection of egg mass (B); Egg mass of Meloidogyne sp. (C); Individual egg mass as observed under 40 × of light microscope (D); J2 stage of M. incognita. harvested in water (E).

2.2 Collection of soil samples

Soil samples were collected from various locations in Tamilnadu and Kerala States in India between February 2018 and January 2019. The samples were taken from agricultural fields, steep terrain, high-altitude grasslands, undisturbed soil, and areas with a high accumulation of organic materials. Exactly, 200 g of soil sample was taken from the surface to a depth of 5 cm with the help of a small shovel and was then placed in properly labelled sterile polythene bags, transported to the laboratory, and processed within 24 h.

2.3 Isolation of nematode-trapping fungi

The soil samples were left to air dry for 6–8 h at room temperature and then crushed in a sterile mortar and pestle to achieve the desired consistency. One gram of soil sample was spread across sterile water agar plates (2% agar; 0.02% chloramphenicol) and incubated at 28°C for 7 d. Subsequently, each plate was inoculated with 100 freshly harvested J2 larvae of Meloidogyne incognita. The plates were continuously monitored for three weeks under a 40 × objective lens of a stereo microscope (Nikon SMZ-745 T) to check for the presence of characteristic trap formation by the fungus. The isolates that showed morphological characteristics of A. oligospora and formation of trapping structures were sub-cultured as 2 × 2 mm growth blocks on fresh corn meal agar (CMA; corn meal infusion − 50 g, agar −15 g, distilled water − 1000 mL) plates, incubated at 28 °C for 7 d until good sporulation was obtained. The fungal spores were harvested by washing the plates with a small quantity of sterile distilled water containing 0.05 % Tween 60 (Chandrawathani et al., 1998). The purified fungal spores were preserved in 60 % of the glycerol stock for long-term storage and further studies.

2.4 Morphological and molecular identification of nematode-trapping fungi

Pure culture of the fungal isolates was grown on CMA at 28°C for 7 d until the sporulation was observed. Next, the isolates were subjected to lactophenol cotton blue wet mount preparation and observed under 40 × and 100 × objectives of a compound microscope to check for the characteristic conidiophore and conidiospore morphology of A. oligospora. The isolates that showed these characteristics were then subjected to molecular characterization.

The NTF was grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium for 10 d at 28 °C. DNA was extracted using the EXpure Microbial DNA isolation kit developed by Bogar Bio Bee Stores Pvt. Ltd. and was quantified using a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer. The extracted genomic DNA was then amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) employing fungal-specific internal transcribed spacer (ITS) primers. ITS 1 primer (5′ TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG 3′) and ITS 4 primer (5′ TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC 3′) were used to amplify the partial 18S rRNA gene, ITS1, 5.8S rRNA gene, ITS2 and partial 28S rRNA gene (White et al., 1990). The PCR amplicons were visualized through electrophoresis on 1 % (w/v) agarose gel. The amplicons were purified using exoSAP. The ABI PrismH Big DyeTM Terminator v. 3.0 Ready Reaction Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) was used for sequencing PCR. The sequencing reaction was performed as follows: 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 25 cycles consisting of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C. The unincorporated PCR primers and dNTPs were removed from PCR products by using a Montage PCR Clean-up kit (Millipore). The program MUSCLE 3.7 was used for multiple alignments of sequences (Edgar, 2004). The resulting aligned sequences were cured using the program Gblocks 0. 91b.

Finally, the assembled contiguous sequence of DNA was prepared and a BLAST search of ITS1, 5.8S rRNA gene, ITS2, and partial 28S rRNA gene against GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) database was used to identify isolate(s) to species level. The nucleotide sequences were deposited in GenBank.

2.5 Assessment of optimal media, pH, and temperature for the growth of NTF

The test fungal isolate (8 mm disc from 7 days old pure culture on CMA) was inoculated onto ten different growth media viz., nutrient agar (NA), potato carrot agar (PCA), malt extract agar (MEA), Sabouraud's dextrose agar (SDA), CMA, Czapek- Dox agar (CDA), Czapek's yeast agar (CYA), PDA, rose Bengal agar (RBA) and rice extract agar (REA). The plates were incubated at 28°C for 5 d. To evaluate the optimal pH for the growth, the isolate was inoculated on the optimal growth medium at different pH ranging from 4.0 to 8.0 and incubated at 28 ± 1°C for 5 d. To find the optimal growth temperature, the isolate was inoculated on an optimal growth medium with optimal growth pH and incubated at different temperatures ranging from 4 ± 1°C to 45 ± 1°C for 5 d. The radial growth diameter (mm) was measured on the 3rd, 5th and 7th days, and the mean from quadruplicate plates was calculated and compared (Singh et al., 2005).

2.6 Effect of temperature and pH on the germination of conidiospores

The test isolates were grown on SDA slants for 7 d at 28°C. To dislodge the conidia, a gentle vortex was applied to the culture slant after adding 2 mL of sterile saline (0.9 % NaCl), and the mycelial remnants from the conidial suspension were separated through sterile cotton wool filtration. The optimal temperature and pH for conidiospore germination were determined by the method described by Nagesh et al. (2005). Aliquots of conidial suspension with 100 conidiospores/100 μL were pipetted onto 2 % CMA plates and incubated for 5 d at different temperatures (4 ± 1°C, 15 ± 1°C, 25 ± 1°C, 37 ± 1°C and 45 ± 1°C). Similarly, the conidial suspension was inoculated onto another set of 2 % CMA plates at different pH (4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0) and incubated at optimal temperature for 5 d. The plates were periodically examined under a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ-745 T) to count the number of germinated conidiospores, and individual colonies formed. The percentage of conidiospore germination was then calculated.

2.7 In vitro predaceous activity of the nematode-trapping fungi

The predaceous activity of A. oligospora was tested in vitro following the method described by Galper et al. (1995). A 2 % water agar plate containing a 10-day-old fungal mat (about 1 mm thick) of A. oligospora was prepared. An aliquot of 100 freshly hatched, healthy, and surface-sterilized J2 larvae of M. incognita per 100 μL of the suspension was spread onto the plate. The plates were incubated at 28°C, and the trapping mechanism was observed under a stereomicroscope every 24 h for 7 d. The uncaptured juveniles were collected by washing the plates with sterile water, and their number was counted to estimate the percentage of captured juveniles (Nagesh et al., 2005). Four replicate plates were used, and the mean values were estimated. Data were analyzed using the analysis of variance, and the means were separated according to modified Duncan's multiple range test (Steel and Torrie, 1980).

3 Results

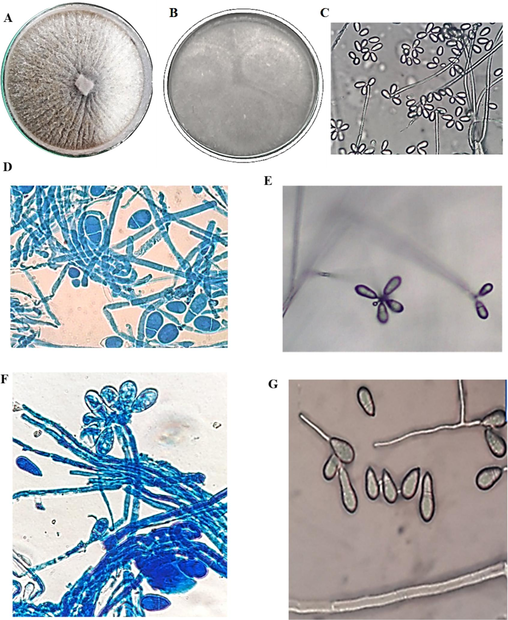

In the present study, out of 110 soil samples processed, only one isolate exhibited the formation of traps and related structures characteristic to the nematode-trapping fungi and captured nematodes. The isolate was from the soil containing the debris of decaying vegetable matter in Coimbatore (11.0329° N, 77.0348° E), Tamilnadu state, India. On CMA, the mycelium radiated out from the point of inoculation. Microscopic morphology after lactophenol cotton blue staining revealed the presence of sparse mycelium with branched hyphae and the erect conidiophore bearing at least six conidiospores at their tips. The conidia were ovoid, two-celled with the apical cell being larger than the basal cell (Fig. 2). The microscopic morphology of the isolate matched with the description of Drechsler (1937) and Haard (1968) for Arthrobotrys oligospora. Further, the morphological characteristics were compared to that of A. oligospora (MTCC − 2103) for quality control purposes. The isolate identity was further confirmed with ITS 1 & 2 and 58s rRNA sequencing, and the sequences were submitted to the GenBank (Orbilia oligospora PSGSS01, Accession Number: ON 820166]. The isolate A. oligospora PSGSS01 is maintained at the Mycology Laboratory, PSG College of Arts & Science, Coimbatore, India.

Morphological observations of A. oligospora PSGSS01 – Colonies on potato carrot agar (A), corn meal agar (B); Direct observation of hyphae and conidia on water agar at 100 × (C); Hyphae and conidia from potato carrot agar after lactophenol cotton blue staining under 100 × (D); Conidia arranged in cluster on conidiophore on water agar under 100 × (E); Conidia arranged in cluster on conidiophore visualized after lactophenol cotton blue staining under 100 × (F); Germ tube formation in the distal cell of two-cell pear-shaped conidia (G).

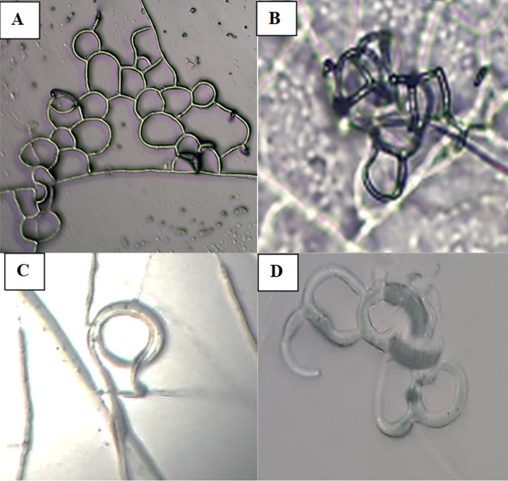

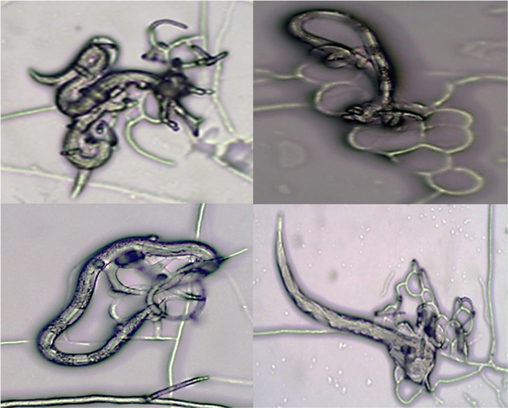

The study also analysed the morphological characteristics of A. oligospora PSGSS01 in the presence of freshly prepared J2 stage larvae of M. incognita. The nematode-infested pure culture of A. oligospora PSGSS01 produced a specialized mycelial network required for predacious activity. The study documented the formation of three-dimensional hyphal traps by A. oligospora PSGSS01 within 24 h of nematode induction. The isolate formed an adhesive network with clearly visible constricting rings and adhesive knobs. In the preliminary analysis, it was found that the J2 larvae of M. incognita were effectively trapped by the A. oligospora PSGSS01 after 24 h of induction (Figs. 3 and 4).

Microscopic morphology of A. oligospora PSGSS01 after induction with Meloidogyne sp. on 2% corn meal agar medium under 40 × – Three-dimensional adhesive network (A&B); Constricting ring on hyphae (C); Adhesive knobs (D).

Second-stage juveniles of Meloidogyne sp. trapped by A. oligospora PSGSS01 on 2% corn meal agar medium under 40 ×.

Of the 10 different media that were evaluated for the optimal growth of A. oligospora PSGSS01, the highest radial growth diameter (80 mm) was observed on (CMA) and SDA followed by PDA (73 mm), CDA (70 mm), and PCA (62 mm). A. oligospora (MTCC-2103) recorded similar growth patterns on CDA, NA and CMA while on all the other media, it exhibited lesser growth when compared to A. oligospora PSGSS01 (Table1). For both isolates, the least growth diameter was recorded on RBA. Values are means of four replicated plates; Means followed by the same letter within a column are not significantly different (P > 0.05) according to modified Duncan’s multiple range test.

S. No.

Medium

Mean radial growth diameter (mm) on 5th day of incubation

A. oligospora

PSGSS01

A. oligospora

(MTCC-2103)

1.

Sabouraud’s dextrose agar

80a

(8.944)70b

(8.367)

2.

Czapek dox agar

70b

(8.367)70b

(8.367)

3.

Potato carrot agar

62c

(7.820)54c

(7.287)

4.

Potato dextrose agar

73ab

(8.494)65b

(8.007)

5.

Malt extract agar

36d

(5.999)28d

(5.477)

6.

Czapek yeast agar

30e

(5.477)28d

(5.477)

7.

Rose Bengal agar

28e

(5.290)26d

(5.290)

8.

Rice extract agar

40d

(6.325)30d

(5.264)

9.

Nutrient agar

30e

(5.477)30d

(5.097)

10.

Corn meal agar

80a

(8.944)80a

(8.944)

CD (0.05) = 0.450

CV = 4.383

CD (0.05) = 0.557

CV = 5.710

As CMA recorded the highest radial growth diameter, the same was used for the assessment of optimal temperature and pH for the germination of conidiospores, radial growth, and sporulation of A. oligospora PSGSS01. At 25°C and pH 5.0, the highest values were observed for growth diameter (90 mm) & germination of conidiospores (100 %), the shortest time required for sporulation (7 d and 10 d) and maximum production of conidiospores (4 × 106 and 5 × 106). Exactly, 82 % of conidiospores germinated at 37 °C and only, ≤ 30 % of conidiospores germinated at all the other temperatures tested. Similar values for the time taken for sporulation (10 d) and conidiospore germination (100 %) were observed at pH 5.0 and 6.0. Therefore, the present analysis concludes that the CMA medium with a pH of 5.0 and at a temperature of 25°C is found to be satisfactory for the growth and sporulation of A. oligospora PSGSS01 (Table 2). Values are means of two replicated plates; Means followed by the same letter within a column are not significantly different according to modified Duncan’s multiple range test.

Growth Parameter analysed

Growth characteristics of A. oligospora PSGSS01

Temperature (°C)

Radial growth (mm)

Conidiospore germination

Sporulation days

Conidiospore production

4

1d

(5.739)15e

(22.643)>25e

(30.747)1x103c

15

50c

(45.000)26d

(30.616)18d

(25.088)2x104c

25

90a

(71.565)100a

(87.134)7a

(15.265)4x106a

37

70b

(57.536)82b

(64.978)12bc

(20.104)3x105b

45

1d

(5.739)30c

(33.211)15bc

(22.786)1x104c

CD (0.05): 8.596

CV: 15.370CD (0.05): 3.318

CV: 4.615CD (0.05): 3.410

CV: 9.926

pH

Radial growth (mm)

Conidiospore germination

Sporulation days

Conidiospore production

4.0

76b

(8.729)23c

(4.873)>25d

(30.000)2x104c

5.0

90a

(9.487)100a

(10.00)10a

(18.392)5x106c

6.0

85a

(9.220)100a

(10.00)10a

(18.392)4x106c

7.0

42c

(6.511)75b

(8.658)15b

(22.764)2x105b

8.0

0d

(0.707)12d

(3.458)18c

(25.088)1x104c

CD (0.05): 0.311

CV: 2.971CD (0.05): 0.235

CV: 2.105CD (0.05): 1.921

CV: 5.560

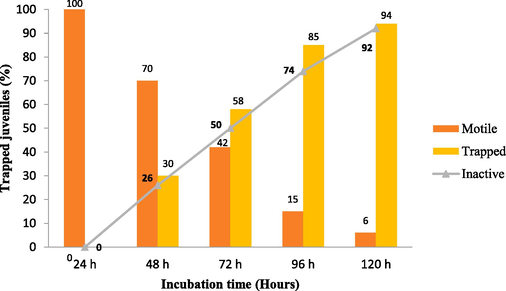

The results of the in vitro predacious activity showed that the number of nematodes captured and killed by A. oligospora PSGSS01 increased with the time of exposure of nematodes to the fungal plate. Trapping was not observed until 24 h. From 48 h to 120 h, there was an increase in the number of trapped nematodes from 30 % to 94 %, respectively. There was a gradual increase of dead J2 larvae over the period (Fig. 5). Overall,> 90 % of nematodes were killed on the 5th day of incubation.

In vitro predacity of A. oligospora against M. incognita J2 juveniles on CMA PSGSS01 medium a 28 °C.

4 Discussion

PPNs have been implicated as one of the major pests of vegetable cultivation among which Meloidogyne spp. are the key damaging PPN genera in the vegetable ecosystem (Gowda et al., 2017). After the root invasion, M. incognita induces the invaded cells to proliferate leading to the formation of galls, a characteristic feature of root-knot nematodes (RKNs; Soliman et al., 2021). As NTF are natural enemies of nematodes, they are suitable candidates for controlling nematodes (Sun et al., 2024). Therefore, the important application of NTF is to be used as an ecological and cost-effective alternative for the control of RKNs (Wernet and Fischer, 2022). According to Wang et al. (2023) A. oligospora is the first documented and widely researched NTF species. The present investigation was undertaken to determine the factors influencing the growth of A. oligospora isolated from this region and to establish its predacious activity upon M. incognita.

Even though a larger number of soil samples (n = 110) were processed for the isolation of NTF, only one isolate showed satisfactory trapping structures and other related features corresponding to NTF. Through morphological examinations and sequencing results the isolate was identified as A. oligospora. The widest-spread predatory fungi are in the family of Orbiliaceae (Ascomycetes) (Moore et al., 2011), and A. oligospora is one such fungus. In A. oligospora, the dimorphic feature is characterized by the saprobic stage and infectious stage (Niu and Zhang, 2011). A. oligospora is a facultative trapper of nematode for nitrogen acquisition (Barron, 1992) and is predominantly found in the rhizosphere soil (Nordbring-Hertz, 2004; Niu and Zhang, 2011; Jiang et al., 2017). Niu and Zhang (2011) stated that A. oligospora has been recorded from Asia, Africa, North and South America, and Australia. Many authors have documented A. oligospora and related species from various places in India (Nagesh et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2005; Kumar and Singh, 2006; Singh et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2015; Namrata et al., 2018; Kassam et al., 2021). The current study documents A. oligospora isolated from the soil containing the debris of decaying vegetable matter in Coimbatore (11.0329° N, 77.0348° E), Tamilnadu state, India.

According to Nordbring-Hertz (2004), A. oligospora forms adhesive network traps following induction by nematodes or nutrient depletion. Similarly, in the present study, the pure culture of A. oligospora PSGSS01 was able to produce the specialized structures only after the induction with J2 larvae of M. incognita. Therefore, it could be concluded that the isolate required nematodes to produce traps on an agar medium. According to Jaffee et al. (1992), the dependence on specialized conditions for trap induction on agar may not be important in soil. Induction is not ecologically important if traps are always induced in the natural environment. However, in the present study other fungi that do not exhibit spontaneous trap formation on agar were not examined. Nordbring-Hertz et al. (2006) and Yang et al. (2007), have stated that the trapping structure formed by these fungi indicated their conversion from saprophytic to predacious lifestyles. Similar results were discussed by Nagesh et al. (2005), Singh et al. (2012) and Wang et al. (2018). Further, Wang et al. (2017) reported that on CMA time required for the formation of traps by A. thaumasia was lesser when compared to PDA, and a greater number of traps were observed on CMA than PDA. The present isolate formed an adhesive network with clearly visible constricting rings and adhesive knobs. Nordbring-Hertz et al. (2004) have detailed the adhesive network trap, adhesive knob, conidial trap, and hyphal coils produced by A. oligospora strains. Veenhuis et al. (1985) stated that after adhesion, a penetration tube from the mycelial network pierces the nematode cuticle, leading to paralysis and rapid colonization of nematode tissues by the fungus.

The optimal growth media, pH and temperature were determined for A. oligospora PSGSS01. While analysing the radial growth diameter of the isolate on various media, it was found that CMA and SDA were the most suitable media. Kumar et al. (2005) stated that PDA supported the maximum growth of A. dactyloides. Varying growth responses on different media may suggest that the salts and amino acids influence not only the growth but also the formation of predacious structures as evinced by Kassam et al. (2021). In the present study, germination of conidiospores, growth, and sporulation were observed on CMA at all temperatures under analysis, with the highest values recorded at 25°C and pH 5.0 (Table 2). Gomez et al. (2003) described that two Cuban isolates of A. oligospora showed the highest growth at 25°C and least growth at 4°C and conidiospore formation differed at varying temperatures. According to Kumar et al. (2005), the differences in growth and sporulation of A. oligospora on a specific medium are due to their respective nutritional requirement. Kassam et al. (2021) stated that the growth rate of A. thaumasia was significantly higher in CMA, and maximum sporulation was observed in RBA. In the present study, the least growth diameter was recorded on RBA. However, the current results have given an idea of the optimal growth parameters to design a suitable low-cost medium for the mass cultivation of A. oligospora PSGSS01.

A. oligospora PSGSS01 could trap the nematodes only after 24 h of nematode induction and thereafter, a gradual increase in the number of trapped nematodes and dead nematodes was recorded. Nagesh et al. (2005) documented the increase of trapped nematodes from 22 % to 86 % throughout 48 h to 96 h by A. oligospora. According to Singh et al. (2012), A. oligospora VSN−1 killed 66.8 % M. incognita (J2) within seven days at 25 ± 2°C. Mexican isolates of A. oligospora (n = 7) were able to capture 58.91 % of larvae of Haemonchus contortus (Arroyo-Balán et al., 2021). However, in the present study, it was found that >90 % of nematodes were killed on the 5th day of incubation.

5 Conclusion

The present study has not only isolated NTF from Coimbatore, India but also evaluated the optimal growth conditions for the isolate. The in vitro predacious efficacy has desirable outcomes. It could be concluded that A. oligospora PSGSS01 is a potential candidate for the development of a biocontrol agent against RKNs.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sreeram Suresh: Methodology, Investigation, Analysis. Shanthi Annaiyan: Conceptualization. Coimbatore Subramanian Shobana: Conceptualization, Methodology, Analysis, Writing – original draft, Supervision. Amal Mohamed AlGarawi: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation. Ashraf Atef Hatamleh: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation. Selvaraj Arokiyaraj: Conceptualization, Validation.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, for the support. The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers supporting project number (RSPD2024R1095) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- High predatory capacity of a novel Arthrobotrys oligospora variety on the ovine gastrointestinal nematode Haemonchus contortus (Rhabditomorpha: Trichostrongylidae) Pathogens.. 2021;10:815.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lignolytic and cellulolytic fungi as predators and parasites. In: Carroll G.C., Wicklow D.T., eds. The Fungal Community: Its Organization and Role in the Ecosystem. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1992. p. :311-326.

- [Google Scholar]

- The control of free-living stages of Strongylodes papillorus by the nematophagous fungi, Arthrobotrys oligospora. Vet. Parasitol.. 1998;76:321-325.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of an Indian isolate of Arthrobotrys musiformis, a possible biocontrol candidate against round worms. Vet. Parasitol.. 2002;16:17-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Some hyphomycetes that prey on free-living terricolous nematodes. Mycologia.. 1937;29:447-552.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biological characteristics and effects of two strains of Arthrobotrys oligospora from Senegal on Meloidogyne species parasitizing tomato plants. Biocontrol Sci.. 1995;5:517-525.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2004;32:1792-1797.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Simple screening methods for assessing the predaceous activity of nematode-trapping fungi. Nematologica.. 1995;41:130-140.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification and characterization of Cuban isolates of nematode-trapping fungi. Revista De Proteccion Vegetal.. 2003;18:53-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gowda, M.T., Rai, A.B., Singh, B., 2017. Root Knot Nematode: A threat to Vegetable Production and its Management. IIVR Technical Bulletin No.76. IIVR, Varanasi.

- Taxonomic studies on the genus Arthrobotrys corda. Mycologia.. 1968;60:1140-1159.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trap production by nematophagous fungi growing from parasitized nematodes. Phytopathology.. 1992;82:615-620.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A rapid centrifugal-flotation technique for separating nematodes from soil. Plant Dis. Rep.. 1964;48:692.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification, characterization, and evaluation of nematophagous fungal species of Arthrobotrys and Tolypocladium for the management of Meloidogyne incognita. Front. Microbiol.. 2021;12(1–16):790223

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crop loss estimations due to plant-parasitic nematodes in major crops in India. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett.. 2020;43:409-412.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Screening of different media and substrates for cultural variability and mass culture of Arthrobotrys dactyloides Drechsler. Mycobiology.. 2005;33:215-222.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Variability in Indian isolates of Arthrobotrys dactyloides Drechsler: a nematode-trapping fungus. Curr. Microbiol.. 2006;2006(52):293-299.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of germination and carnivorous activities of a nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys dactyloides in fungistatic and fungicidal soil environment. Biological Control. 2015;82:76-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 21st Century Guidebook to Fungi (second ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

- Isolation, in vitro characterization and predaceous activity of an Indian isolate of the fungus, Arthrobotrys oligospora on the root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Nematol. Medit.. 2005;33:179-183.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of temperature and light on growth, capture and predation of Haemonchus contortus by Arthrobotrys oligospora. J. Vet. Parasitol.. 2018;32:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Arthrobotrys oligospora: a model organism for understanding the interaction between fungi and nematodes. Mycology.. 2011;2:59-78.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Morphogenesis in the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora-an extensive plasticity of infection structures. Mycologist.. 2004;18:125-133.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nematophagous Fungi. In: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2006. p. :1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of culture filtrates from the nematophagous fungus Verticillium leptobactrum on viability of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2010;26:2285-2289.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological variations in conidia of Arthrobotrys oligospora on different media. Mycobiology.. 2005;33:118-120.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of biocontrol potential of Arthrobotrys oligospora against Meloidogyne graminicola and Rhizoctonia solani in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Biocontrol Sci.. 2012;60:262-270.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Suppression of root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita on tomato plants using the nematode trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora Fresenius. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2021;131:2402-2415.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Principles and procedures of Statistics. A biometrical Approach (second ed.). New York: McGraw- Hill Book Co.; 1980.

- The efficacy of nematicidal strain Syncephalastrum racemosum. Ann. Microbiol.. 2008;58:369-373.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolites from a global regulator engineered strain of Pseudomonas lurida and their inducement of trap formation in Arthrobotrys oligospora. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric.. 2024;11:25.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of the nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia on nematode and microbial populations. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci.. 2005;70:81-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of fate of electron-dense microbodies in trap cells of the nematophagous fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. g.. 1985;51:399-407.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Integrated metabolomics and morphogenesis reveal volatile signaling of the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2018;84:e02749-e02817.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in life history transition with nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora and its application in sustainable agriculture. Pathogens.. 2023;12:367.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, Identification, and characterisation of the nematophagous fungus Arthrobotrys thaumasia (Monacrosporium thaumasium) from China. Biocontrol Sci. Technol.. 2017;27:378-392.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Establishment of Arthrobotrys flagrans as biocontrol agent against the root pathogenic nematode Xiphinema index. Environ. Microbiol.. 2022;25:283-293.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S., Taylor, J., 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, in: Innes, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.S., White, T.J. (Eds.), OCR Protocols. Academic Press. London, U.K. pp. 315–322. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1.

- Evolution of nematode-trapping cells of predatory fungi of the Orbiliaceae based on evidence from rRNA-encoding DNA and multiprotein sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8379-8384.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]