Isolation and characterization of novel carotenoid pigment from marine Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 and their biological applications

⁎Corresponding author. nishap@mesmarampally.org (Nisha Pallath)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Background

Numerous types of carotenoids with other structures are produced by organisms like bacteria, fungi, algae, yeast, higher plants, etc. In the present study, carotenoid pigment-producing, orange or red-pigmented organisms were isolated from scraping from the ship hull.

Material and Methods

According to Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, the isolated bright orange pigmented organism was identified based on morphology, biochemical and physiological characters, strain myelin basic protein MBP-2 and identified as Planococcus maritimus.

Results

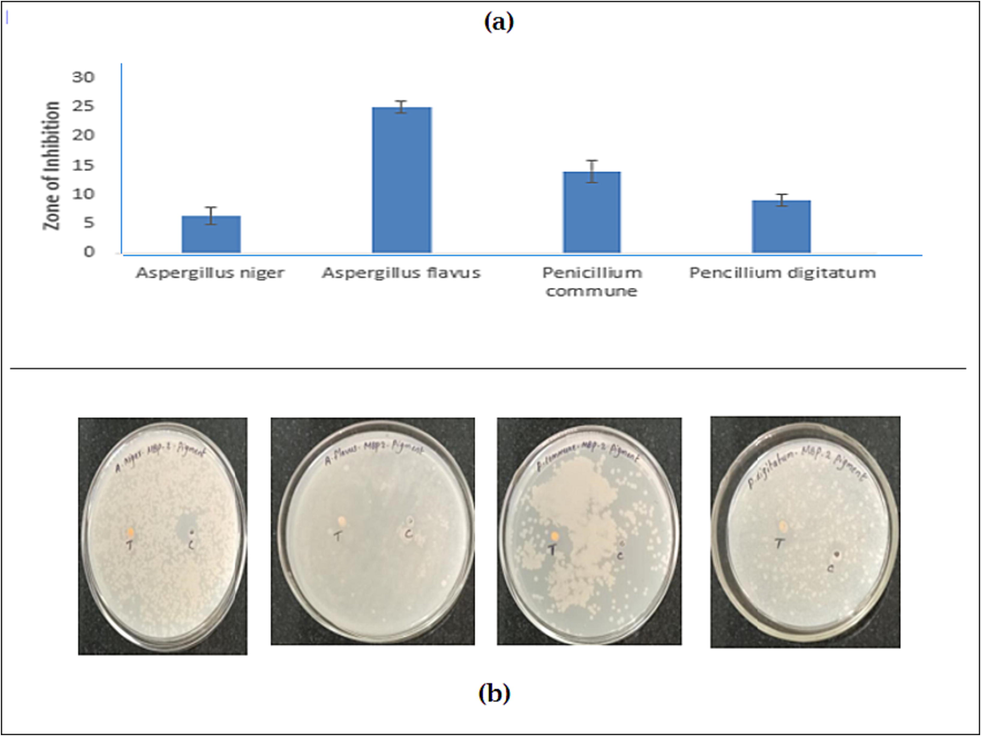

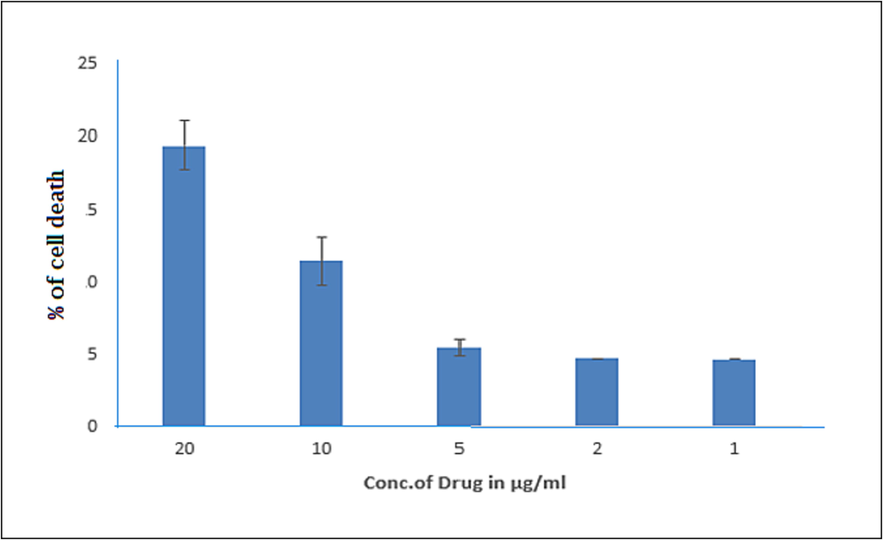

Orange pigment was extracted by solvent extraction method and characterized by using UV–Vis spectroscopy, scanning electron microscope, Transmission electron microscope, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. The Maximum absorbance was obtained at 447 nm, justify the presence carotenoid pigment in MBP-2 and FTIR results reveals the same. The antibacterial activities were performed against gram positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) was 6 ± 0.12 mm, Bacillus cereus (ATCC 14579) was 12.3 ± 1.02 mm and gram negative Escherichia coli was 5.8 ± 0.91 mm, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 39315) was 5.6 ± 1.12 mm and Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 13313) was 11.6 ± 1.01. Furthermore antifungal activities were tested against Aspergillus niger (5 ± 2.15 mm), Aspergillus flavus (25 ± 0.85 mm), Pencillium commune( 14.8 ± 1.15 mm), Pencillium digitatum (12.0 ± 1.8) mmand showed sensitive to some of the bacterial and fungal pathogens. The in-vitro cytotoxic activity of pigment showed 19.46 ± 1.46% of cell death against DLA cells at 20 μl/ml of the drug concentration.

Conclusion

The isolated orange carotenoid is a good source to treat antimicrobial, antifungal and anticancer activates and further study to be implemented.

Keywords

Planococcus maritimus

Orange pigments

Antimicrobial

Antifungal

Cytotoxicity

1 Introduction

Natural pigments and synthetic colours are widely employed in many aspects of daily life, including food, feed, textiles, paper, printing ink, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Color additives are necessary in the food industry since color is crucial in determining whether a consumer would accept a food product. As a result, several artificial food colours have been produced, many of which have adverse side effects. Uses of natural additives are becoming more and more popular because of the toxicity of certain artificial colourants. As consumer awareness has grown, more focus has been placed on the creation of natural colors derived from fruits, vegetables, roots, and microbes (Goswami and Bhowal, 2014). The production of microbial pigments is a relatively new phenomenon. The term “microbial pigments” refers to when microbial cells are used to create the color (Masi et al., 2014). Bacterial pigments are also more environmentally friendly and have better biodegradability. Carotenoids are more observed and studied. Bacterial pigments are used extensively throughout various industries, including the food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, textile, and dye sectors. Recent study identified carotenoid biosynthetic different gene cluster which are produced by Planococcus sp. CP5-4 (Moyo et al., 2022).

Carotenoid pigments are two types of colourants: natural and synthetic. Because they are toxic and non-biodegradable, synthetic colourants are bad for the environment and people’s health. Natural pigment produced by bacteria, fungus, plants, and animals is now in greater demand (Sánchez-Muñoz et al., 2020). Bacterial pigments have been shown to have antibacterial (Boontosaeng et al., 2016), antioxidant (Manimala and Murugesan, 2014), and anticancer action, and they may play a significant role as a food coloring additive (Tibor, 2007). among the different colors claimed to be produced by bacteria. Two types of natural carotenoids and xanthophylls which are in orange and yellow in colour respectively (Berman et al., 2015). Microorganisms that produce carotenoids include Paracoccus, Bacillus, Micrococcus, flavobacterium, Sporobolomyces, Blakeslea trispora, Rhodotorula, and Phaffia (Manimala and Murugesan, 2014). One of the most common natural pigments found in various plants and microorganisms is carotenoids (Berman et al., 2015). Because of their demonstrated pro vitamin A and antioxidant action, which are yellow, orange, red in color these are employed in the food, cosmetic, and feed industries. About 700 distinct chemical structures with unusual colours and biological characteristics make up these pigment (Stafsness et al., 2010). The lipophilic isoproprenoid molecule known as carotenoids have double bonds that combine to form a light-absorbing chromophore, giving them their coloring properties (Chirstaki et al., 2013). Carotenoids are vulnerable to oxidation, isomerization, and light, heat, acids, and oxygen because of these double bonds (Amorim-Carrihlo et al., 2014). Carotenoids may help bacteria adjust their membrane fluidity so they may live in low-temperature environments. By absorbing or blocking UV light, carotenoid also protects bacterial cells (Dieser et al., 2010). The present study confirmed that the scraping from the ship hull samples producing orange pigmented bacteria Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 and exhibited excellent biological activities including antimicrobial, antifungal and cytotoxicity effects (see Table 1).

| S. No | Drug Concentration (µl/ml) | Live cells | Dead Cells | Total no. of cells | SD | % of cell Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 104 | 5 | 109 | 0 | 4.59 ± 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 104 | 5 | 109 | 0 | 4.59 ± 0 |

| 3 | 5 | 102.5 | 5.25 | 107.75 | 0.59 | 4.88 ± 0.59 |

| 4 | 10 | 92.5 | 10.75 | 103.25 | 1.67 | 10.4 ± 1.67 |

| 5 | 20 | 83.25 | 17.75 | 101 | 1.62 | 17.6 ± 1.62 |

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample and isolation

The experimental samples were collected randomly from marine biofilm sources by scraping from the boat hull with help of a sterile spatula and it shifted to a sterile sample collection bottle. Heterotrophic microbes were isolated by the standard plate method and pure cultures were maintained.

2.2 Identification of MBP-2

We follow the study to Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology, isolated dominant orange pigmented colonies (MBP-2) were obtained from the characteristic features of morphological, biochemical, and physiological and also 16 s rRNA Sequencing analysis.

2.3 Evolutionary relationships of taxa

The Neighbor-Joining method inferred the evolutionary history (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The measurement (%) of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (100 replicates). This analysis involved 128 nucleotide sequences. Evolutionary studies were conducted in MEGA11 Software (Tamura et al., 2021).

2.4 Pigment production

A loop of pure cultured Pre-inoculum was inoculated into Luria Bertani broth and it was incubated for 7 days in a rotary shaker at room temperature and in 120 rpm. The culture was centrifuged for 10 min at 10000 rpm, and the supernatant was mixed with solvents to extract the pigment. Using motor and pestle, pellets were grinding well in dark till pellet became colorless. Extracted pigment in solvent was allow to concentrate and dried pigment was quantified. A modified method carried out pigment production and solvent extraction (Gunasekaran, 2005).

2.5 Confirmatory test for carotenoids

Bacterial colonies were inoculated in to LB broth, incubated at 37 °C at 120 rpm for 3 days. After the desired incubation the broth was centrifuged at 4 °C at 8000 rpm for 10 min. Pellet was washed repeatedly using distilled water and centrifuged. and mixed with methanol and incubate at 60 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered through Whatman No.1 filter paper and collect the orange-pigmented precipitate was mixed with Sulfuric acid and water in a ratio of 1:9. The appearance of blue color is the confirmatory test of carotenoid.

2.6 Pigment extraction

The test organism was inoculated into the nutrient broth with pH 4 and incubated for 72 h at 27 ± 2 °C. Then, centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min and collect supernatant and pellet, the pellet was mixed separately with five solvents (I) Acetone, (II) Ethyl acetate, (III) Isopropanol, (IV) Ethyl alcohol, (V Butyl alcohol. Extracted Pigment in solvents were compared for the selection of powerful solvent.

2.7 Characterizations

Pigment extracted with ethyl alcohol was characterized by SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy and UV–VIS spectrophotometry, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) which is the preferred FTIR spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU 1730 model, JAPAN) in the diffuse reflectance mode operating at a resolution of 0.2 cm−1.

2.8 Antibacterial activity

The antimicrobial efficiency of the orange pigment and green synthesized silver nanoparticle from bacterial culture supernatant were tested by well diffusion method against the bacterial pathogens such as Staphylococcus sp, Bacillus sp, Klebsiella sp, E.coli, Pseudomonas sp. Muller Hinton Agar plates were prepared and wells prepared by cutting media using gel puncture. 50 µg/50 µl of pigment suspension as well as the appropriate control were added. The zone of inhibition of bacterial was measured after incubate at 37 °C for 24–48 h, the inoculum sizes of 1x 106 cfu/mL (CLSI, 2012).

2.9 Antifungal activity

The antifungal activity of bacterial pigment was assayed by using the well diffusion method against Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Pencillium commune, Pencillium digitatum. Pre inoculam was prepared, uniformly spread on to Sabouraud Dextrose Agar plates, and 50 µg/50 µl of sample were added to respective wells with control. The zone of inhibition of fungi was measured in mm after incubation at room temperature for 48–72 h (CLSI, 2012).

2.10 In-Vitro cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity analysis was performed using Dalton’s Lymphoma Ascites cells (DLA). Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion method. Viable cells suspension (1x106 cells in 0.1 ml) was added to tubes containing different concentrations 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 µl/ ml Planococcus maritimus orange pigments and the total volume up to 1 ml using phosphate buffered cell line (PBS) followed (Thavamani et al., 2014; Devanesan and Alsalhi., 2021).

2.11 Statistical evaluation

The statistical evaluation was performed with simple Microsoft excel and mean and standard deviation with > 0.005.

3 Results

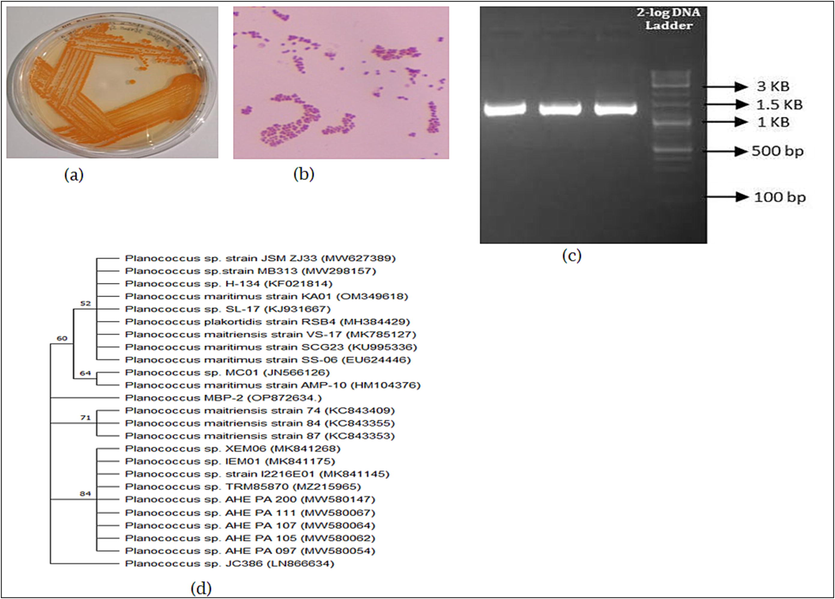

The collected samples of large numbers of orange pigment producing bacteria (Fig. 1a.) were selected (MBP-2) for further investigations. The preliminary identification of bacterial isolate was revealed by Bergeys Manual Determinative Bacteriology (Fig. 1b.) and Molecular Identification. The genomic DNA of MBP-2 was isolated, quality was checked using the Agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) (Fig. 1c.) was captured under UV light using Gel Documentation System (Bio-rad). Isolated DNA shows the molecular weight of 1.5 KB were subjected to PCR. The sequencing reaction was done in PCR thermal cycle and sequence quality was checked using sequence scanner software v1 (Applied Biosystem). Sequences were BLAST in NCBI, shows that MBP-2 was 99.88% similarity with Planococcus maritimus. GenBank accession No– OP872634. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA11.The tree was constructed with maximum likelihood tree, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree and 100 repeated number used with traditional rectangular method. (Fig. 1d.).

- (a) Orange pigment producing bacteria; (b) Identification of bacterial revealed by Bergeys Manual Determinative Bacteriology; (c) Isolated the DNA from MBP-2 and identified by agarose gel electrophoresis; (d) phylogenetic tree analysis showing the Planococcus sp.

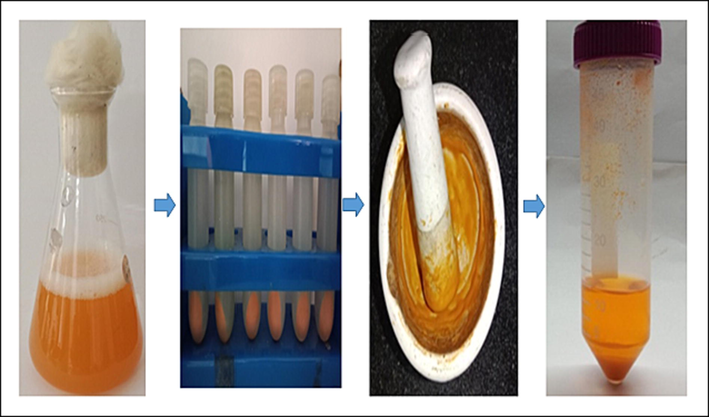

Pigment production was quantified the optimum conditions like, pH 7, Incubation time 72 h by using nutrient broth. The extracted pigment in ethyl alcohol was quantified 2.064 g /L (Fig. 2.). The maximum biomass dry weight and carotenoid production at 96 h and pH 8, were 3.71 g/L and 9.39 mg/100 g respectively. Carotenoid production and dry weight biomass were increased in higher pH than the lower pH studied.

- The optimization process of Orange pigments quantification by using nutrient broth medium (optimum pH 7 at 72 h).

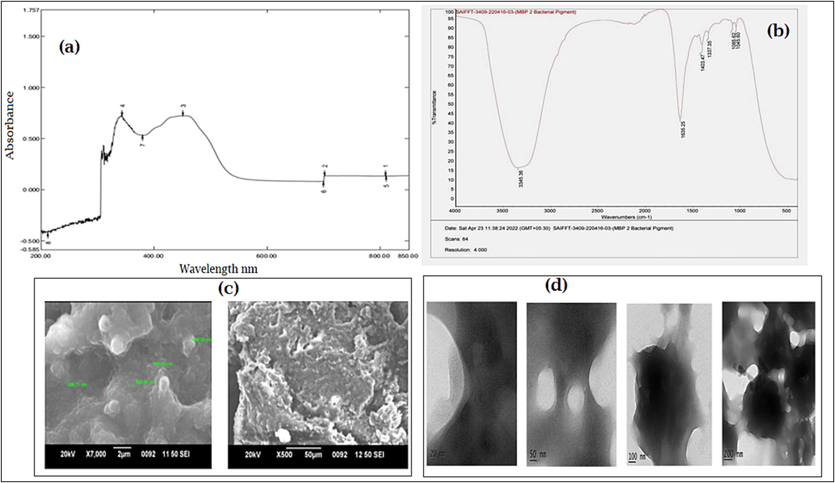

In UV –VIS spectroscopy, maximum absorbance of orange colored pigment was obtained at 447 nm (Fig-3a). It was confirmed the presence of carotenoid pigment. The FTIR spectrum report was analyzed and interpreted corresponding to the standard peak values 3345.36 Symmetrical stretching of Hydroxyl group (–OH), 1635.25 presence of amide, 1403.47 stretching vibration presence of aromatics (C–C) 1357.35 N-O stretching vibrations presence of nitro compounds 1085.62 and 1045.60C-N stretching vibration presence of aliphatic amines (Fig. 3b). FTIR conform the presence of carotenoid. Similar studies reported the FTIR bands at 1653–1661 cm−1 indicates the presence of chlorophyll 1424–1426 cm -1 as -C–H- (CH2) bending vibration from methylene of carotenoids or lycopene, 1366–1367 cm −1 band as the β-ionone ring of β-carotene due to the C–H, (–CH3) symmetrical bending. Surface structures of orange pigment was visualized in various magnification under scanning electron microscope (Fig. 3c) and also used to measurement of transmission electron microscope TEM (Fig. 3d).

- Characterizations of identified pigment producing bacteria (a) Orange colored pigment -UV absorbance; (b) FTIR spectrum of carotenoid pigment from bacterial species; (c) Scanning electron microscopy of Orange color pigment; (d) Transmission electron microscopy of Orange color pigment.

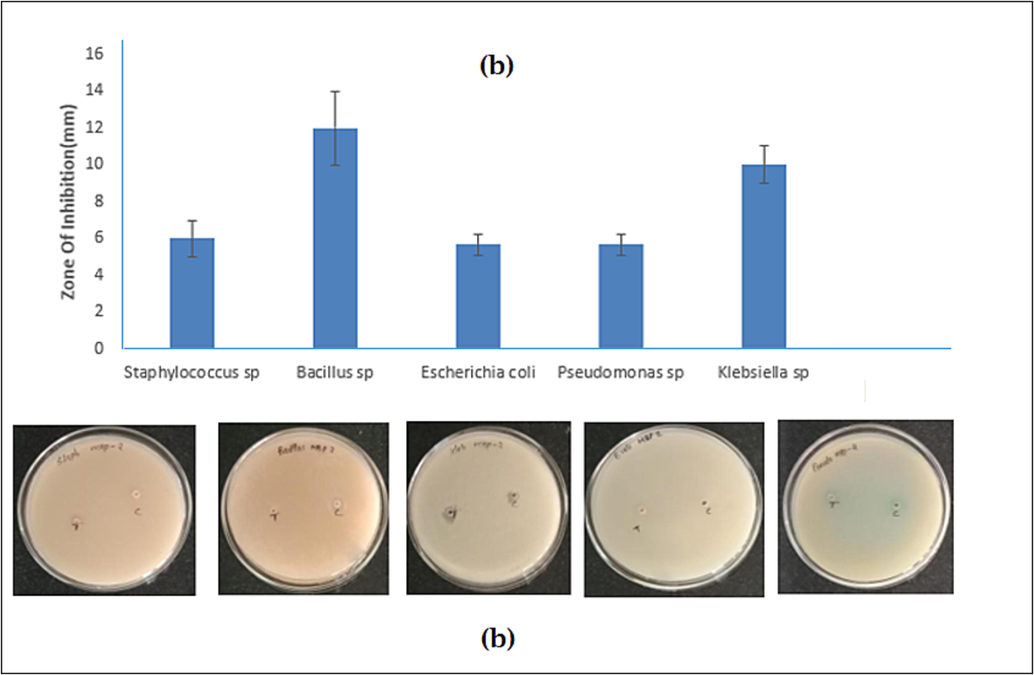

The antibacterial activity of orange pigment was analyzed after the incubation with a different concentrations 40–80 µg/ml concentration of pigment was able to inhibit mostly tested pathogens, the plates were observed for the zone of inhibition (Fig. 4 (a-b). The of zone of inhibition results of both gram positive and gram negative pathogens results were B. cereus was 12.3 ± 1.02 mm, S. aureus was 6 ± 0.12 mm, K. pneumoniae was 11.6 ± 1.01. E. coli was 5.8 ± 0.91 mm and P. aeruginosa was 5.6 ± 1.12 mm.

- The antibacterial activity of orange pigment against Staphylococcus sp., Bacillus sp., Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas sp., Klebsiella sp. (a) Zone of inhibition mm (b) plate observation.

The Antifungal activity of pigment extracted was assayed with different concentration of orange pigment 40–80 µg/ml (Fig. 5 a-b.). Orange pigment showed the excellent inhibition activity against tested organisms was 25 ± 0.85 mm against A. flavus, P. commune was 14.8 ± 1.15 mm, P. digitatum 12.0 ± 1.8 mm and minimal inhibition results was against A. niger was 5 ± 2.15 mm.

- The Antifungal activity of A. niger, A. flavus, P. digitatum, P. commune pigment extract (a) Zone of inhibition mm (b) plate observation.

The pigment shows a good cytotoxicity of 17.6% of cell death against DLA cells at 20 µl (Fig. 6a and b). For the in vitro cytotoxicity analysis, the different concentration of pigment is added with DLA cells in Table 1. The carotenoid pigments from an extremophilic Deinococcus sp UDEC-P1 and Arthrobacter sp.

- Effect of orange pigment on cytotoxicity effects with different concentration by MTT assay in DLA cells.

4 Discussion

In the present investigation isolate orange pigment MBP-2 identified as Planococcus maritimus and studied their biological activities including antimicrobial, antifungal and cytotoxicity effects. There are numerous enzymes are responsible for the formation of pigments (Pandey et al, 2018). Another work on yellow pigment from Micrococcus sp produced maximum carotenoid at 35 °C, pH 6 and at 96 h, the maximum yield was 4.13 g / l and 9.97 mg /100 g of carotenoid in apple pomace based medium (Nisha and Thangavel, 2014; Maoka T, 2019). Psychrotrophic Planococcus maritimus produced maximum carotenoid yield at 10 °C after 6 days of incubation at pH 7 in BHI; the highest production was at 3% NaCl concentration (Kushwaha1 et al., 2020). Psychrotrophic Planococcus maritimus producing carotenoids showed maximum absorbance at tentative peaks 458 nm and 437 nm, with control (Kushwaha1 et al., 2020).

Methanol extract of the carotenoid pigments analyzed using UV–Vis in the 200–800 nm range showed the maximum absorbance at 466 nm as similar observation was reported (Vila et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2001). Similar studies were reported that, most of the carotenoid pigments have maximum absorption range between 375 and –505 nm (Sahin, 2011; Kusmita et al., 2017).

Interestingly, the bands in the range of 1511–1530, 1153–1159 and 1003–1010 cm -1 also represent bacterial carotenoids (Kushwaha et al., 2014). FTIR spectra of carotenoid pigment from bacterial species functional peaks at 1661, 1653, 1654 and 1655 cm-1 the peaks in range between 1600 and 1670 correspond to protein (Suresh et al., 2016) and the peaks of 1425, 1426 and 1424 cm-1, are the vibrations of methylene in Beta carotene standard at 1450.68 cm-1 peak height (Parlog, 2011; Bermejo et al., 2021).

The pigment produced by Planococcus maritimus of the present study exhibited good antibacterial activity against B. cereus and K. pneumoniae. The similar study was reported orange pigment involve the treatment of bacterial pathogens which penetrate to cytoplasmic membrane was broken (Zhao et al., 2016). Recent study was reported that Planococcus maritimus to shield the Caenorhabditis elegans from damaged by Vibrio anguillarum (Li et al., 2021). The present study exhibits excellent antifungal effects of Aspergillus niger, Aspergillu sflavus, Pencillium digitatum,Pencillium commune, the similar effects of antimicrobial and antifungal effects of Planococcus sp halophilic bacterium which are capable to produce the variety of secondary metabolites act as an antioxidant agent (Waghmode et al., 2020). UDEC-A13 were the compound with anticancer activity and were reported to be used as a novel anticancer agent (Tapia et al., 2021). Another study reported the P. maritimus SAMP MCC have a good source of cytotoxic effects with different cell line (Waghmode et al., 2020).

5 Conclusion

The present study concluded, according to Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, the isolated dominant organism Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 was identified. To confirm with different characterizations UV spectrum and FTIR obtained the presence of carotenoid pigment. The carotenoid pigment produced by Planococcus maritimus is exhibited good antibacterial activity against Bacillus sp (12.3 ± 1.02 mm) and Klebsiella sp (11.6 ± 1.01) and also excellent antifungal results were observed for A. flavus ( 25 ± 0.85 mm), P. commune ( 14.8 ± 1.15 mm) and P. digitatum (12.0 ± 1.8 mm). The in-vitro cytotoxic activity of pigment of cell death against DLA cells. This study suggested that, the orange pigmented bacteria Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 may use as an excellent antimicrobial, antifungal and cytotoxic agents.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R398) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Nutritionally important carotenoids as consumer product. Phytochem. Rev.. 2015;14:727-743.

- [Google Scholar]

- β-Carotene biofortification of chia sprouts with plant growth regulators. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2021;168:398-409.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pigments production of bacteria isolated from dried seafood and capability to inhibit microbial pathogens. IOSR. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol.. 2016;10:30-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Functional properties of carotenoids originating from algae. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2013;93:5-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests. Approved Standard. 11th ed. Volume 32 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, NJ, USA: 2012.

- Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using the Flower Extract of Abelmoschus esculentus for Cytotoxicity and Antimicrobial Studies. Int. J. Nanomed.. 2021;16:3343-3356.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carotenoid pigmentation in Antarctic heterotrophic bacteria as a strategy to withstand environmental stresses. Arctic Antarctica and Alpine Research. 2010;42:396-405.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification and characterization of extracellular red pigment producing bacteria isolated from soil. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci.. 2014;3(9):169-176.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity by pigmented psychrotrophic bacterial isolates. Ind. J. Appl. Res.. 2014;4:70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of carotenoids in psychrotrophic bacteria by spectroscopic approach. J. BioSci. Biotechnol.. 2014;3:253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification and characterization of psychrotrophic strain of Planococcus maritimus for glucosylated C30 carotenoid production. Indian J. Experimental Biol.. 2020;58:190-197.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of carotenoid pigments from bacterial symbionts of soft-coral Sarcophyton sp. from North Java Sea. Int. Aquat. Res,. 2017;9:61-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Planococcus maritimus ML1206 Isolated from Wild Oysters Enhances the Survival of Caenorhabditis elegans against Vibrio anguillarum. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19(3):150.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of carotenoid pigment extracted from Sporobolomyces sp. isolated from natural source. J. Appl Nat. Sci.. 2014;6(2):649-653.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure and biosynthesis of carotenoids produced by a novel Planococcus sp. isolated from South Africa. Microb. Cell Fact.. 2022;21:43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of exopolysaccharide from biofilm producing marine bacteria. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2014;2(8):846-853.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimisation and characterisation of the orange pigment produced by a cold adapted strain of Penicillium sp. (GBPI_P155) isolated from mountain ecosystem. Mycology. 2018;9(2):81-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parlog, R.M., 2011. Metabolomic studies applied on different sea buckthorn (Hippophae Rhamnoides L.) varieties, Ph.D. Thesis Wageningen University at Netherlands. http://usamvcluj.ro/en/files/teze/en/2011/parlog.pdf.

- Significance of absorption spectra for the chemotaxonomic characterization of pigmented bacteria. Turkish J. Biol.. 2011;35(2):167-175.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 1987;4:406-425.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of fungal and bacterial pigments and their applications. In Biotechnological production of bioactive compounds 2020:327-361.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of marine pigmented bacteria from Norwegian coastal waters and screening for carotenoids with UVA-blue light absorbing properties. J. Microbiol.. 2010;48:16-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- FTIR and multivariate analysis to study the effect of bulk and nano copper oxide on peanut plant leaves. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Devices. 2016;1(3):343-350.

- [Google Scholar]

- MEGA 11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antiproliferative activity of carotenoid pigments produced by extremophile bacteria. Nat. product res.. 2021;35(22):4638-4642.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer activity of Cocculus hirsutus against Dalton's lymphoma ascites (DLA) cells in mice. Pharm. Biol.. 2014;52(7):867-872.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liquid Chromatography of natural pigments and synthetic dyes. J. Chromatographic Lib.. 2007;71:1-591.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carotenoids from heterotrophic bacteria isolated from Fildes Peninsula, King George Island, Antarctica. Biotechnol. Rep. (Amst.). 2019;21:e00306

- [Google Scholar]

- Planococcus species - an imminent resource to explore biosurfactant and bioactive metabolites for industrial applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.. 2020;8:996.

- [Google Scholar]

- The presence of 9-cis-beta-carotene in cytochrome b(6)f complex from spinach. BBA. 2001;1506(3):182-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial characteristics of orange pigment extracted from monascus pigments against escherichia coli. Czech J. Food Sci.. 2016;34(3):197-203.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102872.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: