Translate this page into:

IS711 sequencing of Brucella melitensis and Brucella abortus strains, and use of microchip-based real-time PCR for rapid monitoring

⁎Corresponding authors at: Department of Public Health, College of Public Health and Health Informatics, Qassim University, Al-Bukairiyah, Saudi Arabia (A. Elbehiry) and Department of Botany and Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia (I. Moussa). ar.elbehiry@qu.edu.sa (Ayman Elbehiry)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

In animal production systems around the world, brucellosis is a serious zoonotic disease that creates public health hazards and losses in economic terms. The aim of the study is to genotype and molecularly characterize Brucella melitensis (B. melitensis) and Brucella abortus (B. abortus) collected from different animal species and humans. A total of 50 isolates of Brucella species (16B. melitensis and 34B. abortus) were isolated from 1081 animal and human samples using a culture technique, followed by biochemical identification using the Vitek 2 compact system and proteomic identification using mass spectrometry technology. Molecular genotyping was performed on all isolates using multiplex real-time PCR. Six isolates from each genotype of Brucella species were selected and genetically evaluated by IS711 insertion sequences. Microchips-based real-time PCR for Brucella species identification was performed on twelve genetically characterized isolates as a first attempt. Forty-four (88%) isolates of Brucella species were detected using multiplex real-time PCR. Based on IS711 nucleotide sequencing, twelve isolates were phylogenetically clustered into their specific clusters. The results of the comparative analysis of conventional real time and microchips-based real time indicated that the later is faster and qualitatively more sensitive than conventional real time; however, further studies are needed to ensure that it is capable of serving as a gold standard alternative for Brucella species monitoring.

Keywords

Brucella species

Phylogenetic analysis

microchip-based real-time PCR

IS711 sequencing

1 Introduction

Brucellosis is one of the most common zoonotic disease with public health importance and industrial farming systems around the world suffer substantial financial losses as a result of it. (Seleem et al., 2010; Janowicz et al., 2018). The disease remains endemic in the Middle East despite being well-controlled in western countries. (Kirk et al., 2015). Brucella is a gram negative intracellular bacterium that cause disease in domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep, goats and camels (Richomme et al., 2006; Saeed et al., 2019). All of the Brucella species identified from livestock, including Brucella melitensis (B. melitensis), Brucella abortus (B. abortus), Brucella suis (B. suis), and Brucella canis (B. canis), are virulent to humans (Al Jindan, 2021). Human-animal contact and environmental boundaries are often points of transmission of Brucella strains that infect humans and animals (Assenga et al., 2015; Godfroid, 2017) since humans, livestock, and wildlife often share the same habitats. The humans’ infection with brucellosis was frequently due to damaged skin during direct contact with infected parturition materials as in gynaecological examination or as in examining and flaying slaughtered animals. Infection could be also through the mucous membranes (mucosa) and airways. Moreover, infection could be occurred during handling the infected animals' manure (Solecki, 1999; Galinska and Zagórski, 2013). While infections by ingestion of infected milk or dairy products are rare (Solecki, 1999). Middle East has an endemic case of brucellosis (Greco et al., 2018). B. abortus and B. melitensis have been isolated from animals and Humans (Sayour and Sayour, 2018; Sayour et al., 2020), while B. suis has only been isolated from animal (Khan et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2020). Generally, diagnosis of brucellosis is based on classical isolation and identification methods, serological tests or molecular techniques (Boussetta, 1991;Yagupsky et al., 2019).

Many different methods have been used worldwide to identify and characterize Brucella species and determine how they spread to other mammals, including human (Ntirandekura et al., 2020). Isolation is considered a gold slandered for diagnosis but has many disadvantages such as, need prolonged time and poses a high risk of infection to the veterinarians work with it. Moreover, to handle samples and live bacteria for ultimate identification and biotyping, level 3 biocontainment facilities and highly qualified technical employees are required. (Yu and Nielsen, 2010; Khan and Zahoor, 2018). Fast and precise diagnostic technologies are necessary in order to prevent disease transmission from animals to humans, reduce health risks, and minimize economic losses. The most effective diagnostic approach is the PCR test in order to detect Brucella strains (Yu and Nielsen, 2010; Khan and Zahoor, 2018). Microchip real-time PCR is considered as a friendly alternative to traditional real-time PCR. It has been shown to deliver reliable, sensitive, and specific results in less time (Cojocaru et al., 2021).

Molecular and computational techniques are providing us with an improved understanding of how Brucella species differ in terms of evolutionary development, specificity, and pathogenicity in various hosts (Vidal et al., 2018). For the purpose of establishing relationships and grouping of Brucella species, phylogenetic analyses based on random repeats, genomic loci and 16S rRNA gene sequencing are useful (Menshawy et al., 2014; Shome et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2018). A high homology of DNA is found between Brucella species, with more than 90 %. Based on the polymorphism of the IS711 insertion sequence in the Brucella genome, it is a prospective molecular method for distinguishing between species of Brucella and its biovars (Bricker et al., 1994; Mancilla et al., 2011). Selim et al. (2019) explained how identification of the common Brucella and characterization of its molecular characteristics makes it easier to determine the source of the infection and take the appropriate measures to control brucellosis. The current work intends to identify and molecular characterize the isolated samples from several governorates in Saudi Arabia and Egypt and throw the light on rapid technique for Brucella species diagnosis.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Ethical statement

A written authorization or ethical approval were not necessary for this study because neither humans nor animals actively participated. Neither human nor animal samples were used. Our only source of bacteria was routine medical testing or strain collection. As a result, none of the clinical strains were obtained from patients or animals for use in this study. Samples obtained from routine diagnostic procedures were used instead.

2.2 Samples collections, isolation and identification

In Saudi Arabia's Al-Qassim province, samples of milk, vaginal swabs, and blood from 364 animals with a high rate of brucellosis, and 70 human blood samples from individuals who suffered from hyperthermia after close contact with suspect animals were collected. Moreover, 617 different tissues (spleen and lymph nodes) of aborted fetuses or animal carcasses and milk were collected from Egyptian governorates. From cow and goat farms, we collected 15 ml of each milk and blood sample, as well as vaginal swabs. A tissue sample was collected aseptically, extraneous materials were removed, and tissue samples were sliced into small pieces and then macerated in sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS), as described in the OIE manual (2018) (OIE. Brucellosis et al., 2018). The biosafety level two (BSL2) was applied to all microbiological samples deemed to have relatively high impacts. In brief, the samples were rotated at 6000 rpm for 10 min to concentrate the organism, after which the sediment was inoculated onto a specific, antibiotic-containing medium (Brucella Selective Agar), after which the cultured plates were examined for Brucella species on the 4th day and then on a daily basis throughout the next 2–4 weeks at 37 °C in the existence of 10 % CO2. After several subcultures, the Brucella colonies appeared spherical, shiny, pinpointed, and honey-colored. The bacterial colonies were then identified biochemically using both the Vitek 2 Compact System (bioMérieux, France) and other similar approaches such as catalase activity, oxidase activity, CO2 requirements, urease, hydrogen sulfide production, lactose fermentation, and nitrate reduction. The MALDI Biotyper (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) was used to identify Brucella species from their proteomic data.

2.3 DNA extraction and molecular detection

2.3.1 Conventional real time PCR

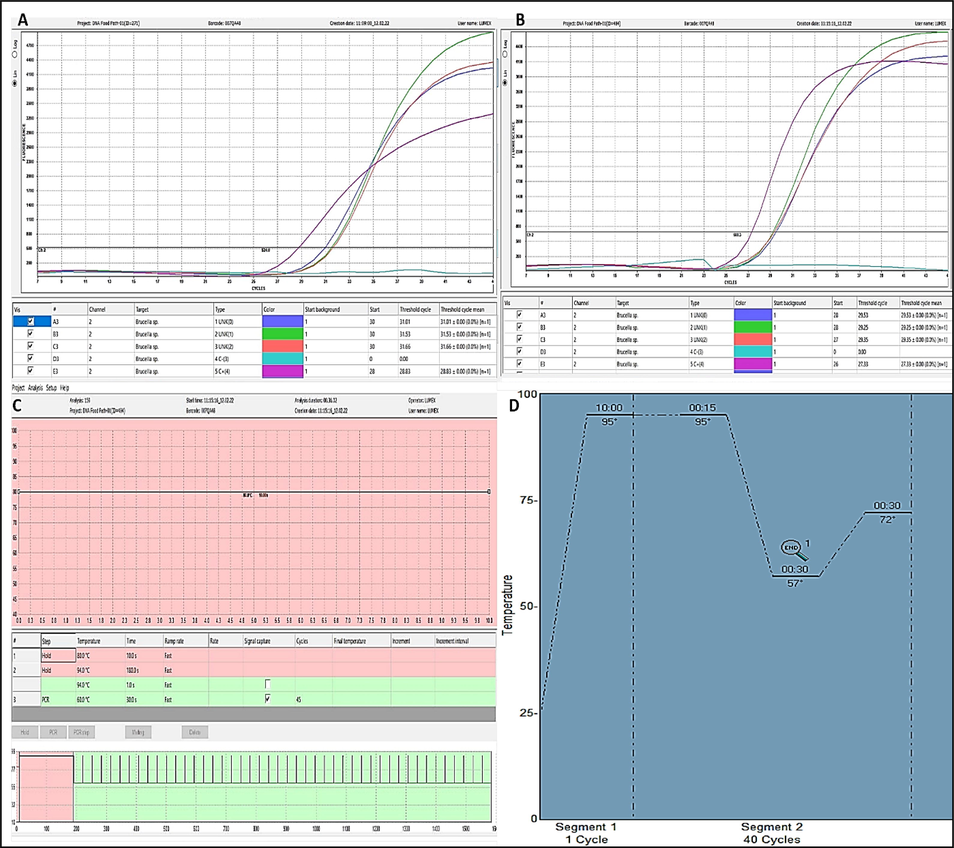

The biochemical confirmed colonies were subjected to molecular detection by standard conventional real time PCR. At first the DNA was extracted from bacterial pellet using GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (thermofisher, cat# K0722) according to manufacturer’s instruction. The extracted DNA was detected for Brucella species by uniplex real time PCR. Then genotyped for B. abortus and B. meletensis by multiplex realtime PCR. The primers and probes used are listed in Table 1. The kit used for standard real time PCR is Ambion™, Path-ID™ (applied biosystem, cat# 4388644 M). The master mix was prepared by adding 12.5 µl of 2✕ qPCR Master Mix and 0.5 µl of each primer (50 pmol) and 0.125 µl of probe (30 pmol) and 6.375 µl nuclease-free water to adjust the final volume 25 µl, finally 5 µl of the extracted DNA was added. The thermal profile starts with enzyme activation and DNA denaturation at 95C° for 10 min. The amplification cycles were done at 95C° for 15 sec. and 57C° for 30 sec., finaly 72C° for 30 sec. (40 cycles) for Brucella species and B. melitensis and B. abortus genotyping. The conventional real time PCR was conducted in Stratagene MX30005P thermal cycler machine (Aligent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

S

Genotype

Primer Sequence

PCR type

Reference

1

Brucella species

F

GCTCGGTTGCCAATATCAATGC

Rel time PCR

(Dal et al., 2019)

R

GGGTAAAGCGTCGCCAGAAG

Probe

FAM-AAATCTTCCACCTTGCCCTTGCCATCA-Tamra

2

B. melitensis

F

AACAAGCGGCACCCCTAAAA

Multiplex Real time PCR (Genotyping)

R

CATGCGCTATGATCTGGTTACG

Probe

FAM-CAGGAGTGTTTCGGCTCAGAATAATCCACA-Tamra

3

B. abortus

F

GCGGCTTTTCTATCACGGTATTC

R

CATGCGCTATGATCTGGTTACG

Probe

HEXCGCTCATGCTCGCCAGACTTCAATG-Tamra

4

B. melitensis

Bm

AAATCGCGTCCTTGCTGGTCTGA

Conventional PCR and sequencing

(Che et al., 2019)

IS711

TGCCGATCACTTAAGGGCCTTCAT

5

B. abortus

Ba

GACGAACGGAATTTTTCCAATCCC

IS711

TGCCGATCACTTAAGGGCCTTCAT

2.3.2 Microchip real time PCR

The developed & optimized microchips with lyophilized reagents ready to use by Lumex Instruments for real-time PCR analyzer AriaDNA ™ (lumex, Mission, Canada) were used to detect Brucella species. Two 25.4x25.4x0.5 mm3 glass slides consist the microchip; the bottom slide considers the PCR reaction chamber while the top slid has a thin heater. In the reaction chamber (bottom slid) there are two different size holes; the inlet (2 mm) and outlet (1 mm). A total of 1.2 µl of DNA (six isolates for each genotype) were loaded individually into the reaction chamber through the 2 mm hole. The thermal profile was adjusted as follow with fast ramp rate; 80C° for 10 sec. then 94C° for 180 sec. for activation and initial denaturation followed by amplification cycles at 94C° for 1 sec for denaturation and 60C° for 30 secs for annealing and polymerization for 45 cycles.

2.4 Molecular characterization of the insertion sequence (IS711) by DNA nucleotide sequencing

The IS 711 of 12 samples of both B. abortus and B. melitensis (6 for each genotype) were partially amplified by conventional PCR using Phusion® High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix with HF Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using specific primers (Table 1). The thermal profile as follow; the initial denaturation 98C° for 30 secs then the cycling stage began with denaturation at 98C° for 10 secs, annealing at 65C° (both genotype) for 30 secs then extention at 72C° for 30 secs (35 cycles) and the final extension was at 72C° for 5 min. By using a QIAquick® gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Gmbh, Hilden, Germany), the positive amplicons were purified. Bigdye® Terminator V3.1 cycle sequencing kit was used to conduct the sequence reactions (PerkinElmer, Foster City, CA). The sequencing reactions were purified using a DyeEx® kit (Qiagen, Gmbh, Hilden, Germany) before they were mounted in the Applied Biosystems 3500 xl genetic analyzer machine (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

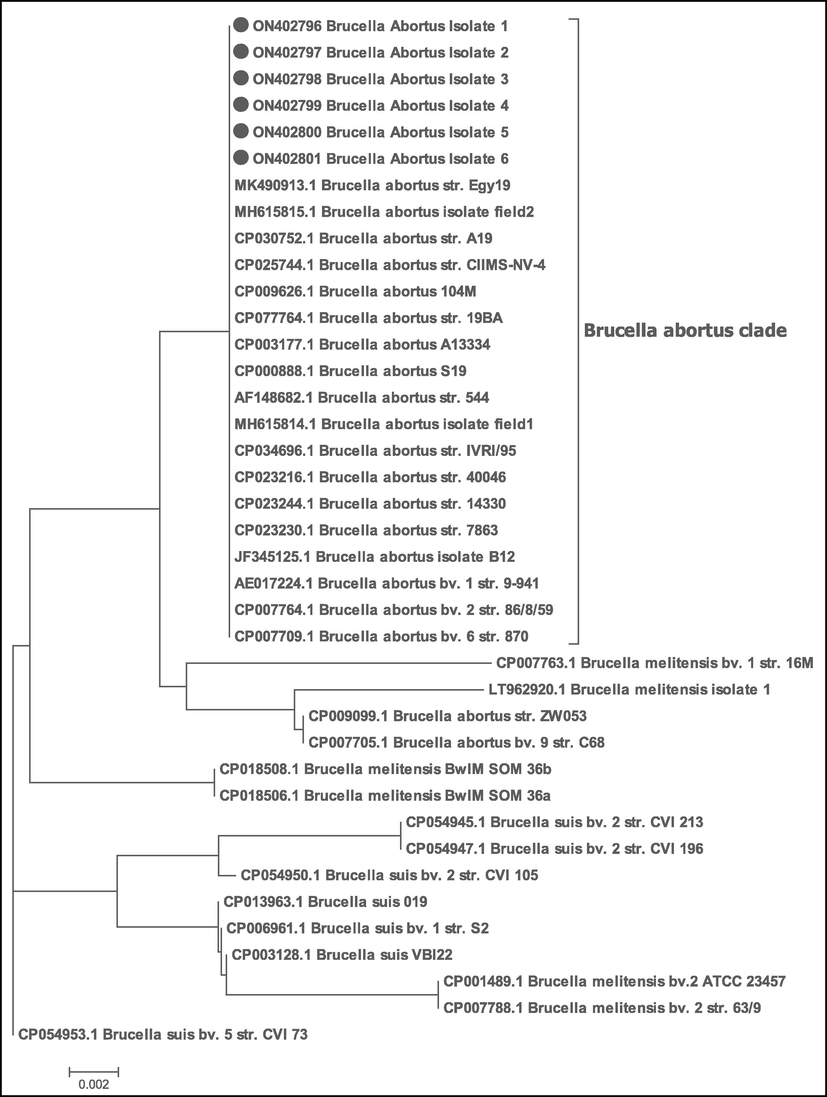

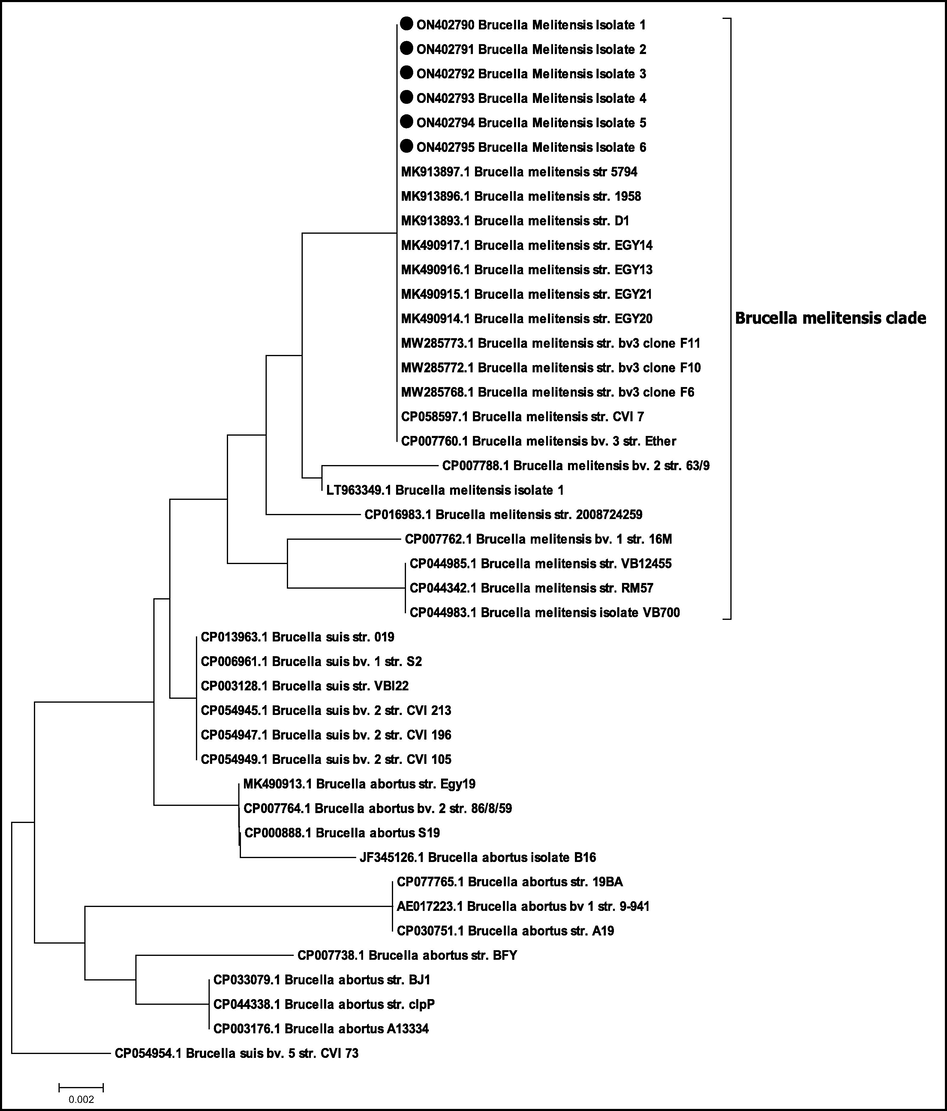

2.5 Alignment and phylogenetic analysis

The nucleotide sequence was aligned using Bioedit 7.2 software (Hall, BioEdit). Mega 7.0.26 software was used to construct a nucleotide phylogenetic tree of the sequenced isolates using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap (Kumar et al., 2016). The analysis of the sequenced isolates was carried out in comparison with different genotypes and biovars retrieved from the Gene Bank, their accession No. included within the taxa of the phylogenetic tree.

3 Results

3.1 Molecular detection of the isolated colonies

A total of 50 Brucella species (16B. melitensis and 34B. abortus) were detected using culture and biochemical methods in this study. In Saudi Arabia's Al-Qassim province, 25Brucella species isolates (11B. melitensis and 14B. abortus). Moreover, 25Brucella species isolates (5B. melitensis and 20B. abortus) in Egyptian governorates. The molecular detection of the biochemical identified isolates (50 isolates) by standard real time PCR revealed that the 44 isolates are positive for Brucella species and genotyped as 29 isolates of B. abortus and 15 isolates of B. melitensis (Fig. 1). The genetically confirmed isolates by gene sequencing were subjected to detection by microchip real time PCR and the comparison between Ct values are shown in Table 2.

Shows the amplification plots of microchip based real time PCR for Brucella species. (a) Amplification plot for a group of selected B. abortus isolates. (b) Amplification plot for a group of the selected B. melitensis isolates. (c) The thermal profile used in this study for microchip based real time PCR for Brucella species. (d) Thermal profile used in conventional Real time PCR.

Isolates No.

Brucella species Real time PCR Ct

B. abortus

Real time PCR Ct

B. melitensis

Real time PCR CtMicrochip Real time PCR Ct.

Genotype

Accession Number in Gene Bank

Isolate No. 1

31.87

Negative

32.91

29.53

B. melitensis

ON402790

Isolate No. 2

30.93

Negative

31.11

29.25

B. melitensis

ON402791

Isolate No. 3

30.62

Negative

30.98

29.35

B. melitensis

ON402792

Isolate No. 4

32.43

Negative

33.99

33.02

B. melitensis

ON402793

Isolate No. 5

21

Negative

21.51

20.16

B. melitensis

ON402794

Isolate No. 6

26.14

Negative

25.00

23.34

B. melitensis

ON402795

Isolate No. 1

34.86

32.37

Negative

31.01

B. abortus

ON402796

Isolate No. 2

33.13

31.17

Negative

31.53

B. abortus

ON402797

Isolate No. 3

33.23

32.94

Negative

31.66

B. abortus

ON402798

Isolate No. 4

19.65

15.56

Negative

15.32

B. abortus

ON402799

Isolate No. 5

17.59

14.67

Negative

14.22

B. abortus

ON402800

Isolate No. 6

24.75

18.53

Negative

20.43

B. abortus

ON402801

3.2 Phylogenetic and sequence analysis

The purified PCR amplicons of the selected positive isolates of 498 bp in case of B. abortus (6 isolates) and 733 bp in case of B. melitensis (6 isolates) were sequenced for insertion Sequence (IS711). The accession Number of the sequenced B. melitensis isolates are from ON402790 to ON402795 and The Accession Number of the sequenced B. abortus isolates are from ON402796 to ON402801. The all partially sequenced isolates of B. abortus are 100 % identity with each other, also the selected isolates of B. melitensis are 100 % identity. The phylogenetic tree clustered all the partially sequenced isolates of B. abortus with the same genotype and all the partially sequenced isolates of B. melitensis with their genotype as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. In both trees for B. abortus and B. melitensis the root of tree is B. suis bv 5str. CVI73 with accession No. CP054953.1 in gene bank.

Phylogenetic tree of the selected isolates (B. abortus) in the study and indicated by filled circle. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method (Tamura et al. 2004). All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016). The tree shows that the all six isolates were clustered with B. abortus isolates and other genotypes strains that retrieved from NCBI. The accession No. of the sequences were illustrated within the taxa.

Phylogenetic tree of the selected isolates (B. melitensis) in the study and indicated by filled circle. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method (Tamura et al., 2004). All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016). The tree shows that the all six isolates were clustered with B. melitensis isolates and other genotypes strains that retrieved from NCBI. The accession No. of the sequences were illustrated within the taxa.

4 Discussion

Brucellosis is a public-health hazard zoonotic disease that causes significant economic losses owing to mortality, morbidity, infertility, abortion, medical care costs as a direct consequence or revenue loss and vaccination as an indirect effect (Donev, 2010; Khan and Zahoor, 2018). The brucellosis has been an endemic disease in middle east for several years (Wareth et al., 2014). In this study, 50 samples were isolated from suspected 1051 clinical samples collected from human and different species (cattle, buffaloes, sheep, and goats). These positive isolates were molecular detected by both systems; standard conventional real time PCR and microchip real time PCR. Forty-four isolates only are positive by real time PCR by both systems for general Brucella species detection representing 88 % of the biochemical characterized isolates. This percent emphasis the specificity of the PCR system used in the current study more over, other studies ensured that sensitivity of real time PCR is more than other tests including bacterial culture and isolation from clinical samples (Ilhan et al., 2008; Yu and Nielsen, 2010).

As far as our knowledge goes, this is the first study to include microchip real time PCR as a test for Brucella species. Microchip real time PCR was positive for all isolates that had been genetically characterized by conventional real time PCR, indicating its accuracy. The microchip real time PCR offers a less expensive and faster equivalent to the most reliable and sensitive test available today (Cojocaru et al., 2021). It engrosses about 30 min versus the standard real time PCR that takes about 80 min and at the same time the Microchip based real time PCR keeps the same gold standard in sensitivity qualitatively as it was measured in the current study, the comparison between the cut threshold (Ct) of the standard real time PCR and Microchip based real time PCR are listed in Table 2 for the sequenced isolates only for proper genetic typing of the isolates under ct comparison between both real time PCR systems. While the quantitative sensitivity of the Microchip based real time PCR tested by other studies (Gill et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2019).

However quantitative sensitivity, specificity and limit of detection criteria are required to ensure the use of the microchip real time PCR in Brucella species monitoring and genotyping as a gold standard alternate in Brucella diagnosis. Regarding to the molecular characterization of the current circulating Brucella species, 6 isolates were selected from genotyped B. abortus and another 6 isolates were selected from genotyped B. melitensis by real time PCR for molecular characterization by partial sequencing of the insertion sequence IS711. The Insertion sequence (IS711) is a short DNA sequences transpose within and between genomes causing genomic rearrangements. It inserts randomly and takes genomic locations. It can have used for distinguishing between different isolates and its typing (Halling et al., 1993; Mancilla et al., 2011).

The selected partially sequenced 6 isolates of B. abortus isolates are identical and the 6 isolates sequenced of B. melitensis are identical too, referring the conservancy of IS711 between sequenced isolates. Despite Brucella being a relatively homogenous and ultramonomorphic genus, there were no differences between isolates obtained from various animals living in various governorates. (Khan et al., 2021). Phylogenetically, the 6 isolates of B. abortus isolates were clustered within the B. abortus clade and the other 6 isolates of B. melitensis were clustered within its clade as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The presence of different biovars for the same Brucella type in its clade of the phylogenetic tree indicating the limitation of the IS711 sequence to differentiate between subspecies or biovars (Whatmore, 2009). In conclusion, the current study spots the light to the urgency of implementation of rapid accurate tests to monitor and genotyping of the Brucella species due to its hazard impact on public health and animal production and reproduction.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education and Qassim University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number (QU-IF-1-4-2).

Funding

The Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education and Qassim University, Saudi Arabia (the project number: QU-IF-1-4-2).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Scenario of pathogenesis and socioeconomic burden of human brucellosis in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;28(1):272-279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of Brucella infection in the human, livestock and wildlife interface in the Katavi-Rukwa ecosystem. Tanzania. BMC veterinary research. 2015;11(1):1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic au laboratoire de la brucellose animale [Laboratory diagnosis of animal brucellosis] Arch. Inst. Pasteur Tunis. 1991;68(3–4):285-293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 1994;32(11):2660-2666.

- [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring the course of Brucella infection with qPCR-based detection. Int. J. Infect. Dis.. 2019;89:66-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microchip RT-PCR detection of nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 samples. J. Mol. Diagn.. 2021;23(6):683-690.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction with serological tests and culture for diagnosing human brucellosis. J. Infect. Public Health. 2019;12(3):337-342.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brucellosis as priority public health challenge in South Eastern European countries. Croat. Med. J.. 2010;51(4):283-284.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brucellosis in humans-etiology, diagnostics, clinical forms. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med.. 2013;20(2):233-238.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification and quantitation of cashmere (pashmina) fiber and wool using novel microchip based real-time PCR technology. Journal of Textile Science and Technology. 2018;04(04):141-150.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brucellosis in livestock and wildlife: zoonotic diseases without pandemic potential in need of innovative one health approaches. Archives of Public Health. 2017;75(1):1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proteomic analyses on an ancient Egyptian cheese and biomolecular evidence of brucellosis. Anal. Chem.. 2018;90(16):9673-9676.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sequence and characterization of an insertion sequence, IS711, from Brucella ovis. Gene. 1993;133(1):123-127.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of culture and PCR for the detection of Brucella melitensis in blood and lymphoid tissues of serologically positive and negative slaughtered sheep. Lett. Appl. Microbiol.. 2008;46(3):301-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- Core genome multilocus sequence typing and single nucleotide polymorphism analysis in the epidemiology of Brucella melitensis infections. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2018;56(9)

- [Google Scholar]

- An improved method of DNA preparation for PCR-based detection of Brucella in raw camel milk samples from Riyadh region and its comparison with immunological methods. J. Food Saf.. 2018;38(1):e12381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serological and molecular identification of Brucella spp. in pigs from Cairo and Giza Governorates. Egypt. Pathogens. 2019;8(4):248.

- [Google Scholar]

- Whole-Genome sequencing for tracing the genetic diversity of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis isolated from livestock in Egypt. Pathogens. 2021;10(6):759.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence and molecular identification of Brucella spp. camels in Egypt. Microorganisms. 2020;8(7):1035.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview of brucellosis in cattle and humans, and its serological and molecular diagnosis in control strategies. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2018;3(2):65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correction: World Health Organization estimates of the global and regional disease burden of 22 foodborne bacterial, protozoal, and viral diseases, 2010: a data synthesis. PLoS Med.. 2015;12(12):e1001940.

- [Google Scholar]

- MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2016;33(7):1870-1874.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of new IS711 insertion sites in Brucella abortus field isolates. BMC Microbiol.. 2011;11(1):1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Menshawy, A., Perez-Sancho, M., Garcia-Seco, T., Hosein, H.I., García, N., Martinez, I., Sayour, A.E., Goyache, J., Azzam, R.A., Dominguez, L. and Alvarez, J., 2014. Assessment of genetic diversity of zoonotic Brucella spp. recovered from livestock in Egypt using multiple locus VNTR analysis. BioMed Research International, 2014.

- Molecular characterization of Brucella species detected in humans and domestic ruminants of pastoral areas in Kagera ecosystem, Tanzania. Veterinary medicine and science. 2020;6(4):711-719.

- [Google Scholar]

- OIE. Brucellosis (Brucella abortus, B. melitensis and B. suis) (infection with B. abortus, B. melitensis and B. suis). In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals, 7th ed.; World Health Organization for Animal Health: Paris, France, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 355–398.

- Contact rates and exposure to inter-species disease transmission in mountain ungulates. Epidemiol. Infect.. 2006;134(1):21-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroepidemiology and the molecular detection of animal brucellosis in Punjab, Pakistan. Microorganisms. 2019;7(10):449.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 1987;4(4):406-425.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sayour, A.E. and Sayour, H.E., 2018, December. Binomial identification of Brucella isolates by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. In: Proceedings of the Second Scientific Conference of Food Safety and Technology, Cairo, Egypt (pp. 25-27).

- MLVA fingerprinting of Brucella melitensis circulating among livestock and cases of sporadic human illness in Egypt. Transbound. Emerg. Dis.. 2020;67(6):2435-2445.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence and molecular characterization of Brucella species in naturally infected cattle and sheep. Prev. Vet. Med.. 2019;171:104756

- [Google Scholar]

- Shome, R., Krithiga, N., Padmashree, B.S., Shome, B.R., Saikia, G.K., Sharma, N.S., Chauhan, H., Chandel, B.S., Rajendhran, J. and Rahman, H., 2016. Genotyping of Indian antigenic, vaccine and field Brucella spp using Multiple Locus Sequence Typing.

- Occupational and para-occupational diseases in agriculture. VI International Seminar on Ergonomics, Work Safety and Occupational Hygiene. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med.. 1999;6(2):171-172.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2004;101(30):11030-11035.

- [Google Scholar]

- A fully portable microchip real-time polymerase chain reaction for rapid detection of pathogen. Electrophoresis. 2019;40(12–13):1699-1707.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview on the phylogenetic classification of Brucella. Revista UDCA Actualidad & Divulgación Científica. 2018;21(1):109-118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Animal brucellosis in Egypt. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2014;8(11):1365-1373.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current understanding of the genetic diversity of Brucella, an expanding genus of zoonotic pathogens. Infect. Genet. Evol.. 2009;9(6):1168-1184.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory diagnosis of human brucellosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.. 2019;33(1):e00073-e00119.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of detection of Brucella spp. by polymerase chain reaction. Croat. Med. J.. 2010;51(4):306-313.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102468.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: