Translate this page into:

Investigation of bioactive constituents and evaluation of in vitro bioactivities of different Setaria glauca extracts

⁎Corresponding authors at: Department of Botany, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. javed.iqbal@bkuc.edu.pk (Javed Iqbal), tmahmood@qau.edu.pk (Tariq Mahmood)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University

Abstract

The aim of this research was to look at the various biological potentials and phytochemical components of S. glauca. Utilizing FT-IR spectroscopy, different functional groups were identified. Tests for total reducing power (TRP), total antioxidant capacity (TAC), and DPPH were employed to assess the antioxidant qualities of a specific medicinal plant. The antibacterial activity of five different strains of bacteria were assessed using the disc diffusion method. Laboratory-cultured nauplii were killed in the brine shrimp lethality experiment to assess the cytotoxic capability. Statistical software version 8.1 was utilized to conduct an analysis of variance (ANOVA), with each experiment being repeated three times. In S. glauca, ten distinct functional groups were found. TAC (SGM = 20.07 AAE/g) and DPPH scavenging capacity (IC50 = 28.38 µg/mL) were noted in the methanol extract of S. glauca (SGM) as well as the total reducing power (TRP) of 62.87 GAE/g was found in SGM. The antibacterial activity was evaluated using several types of bacteria. The maximum zone of inhibition (MI) against P. aeruginosa (ATCC) was found in SGC (12 ± 1.0 mm mean value). The chloroform extract of S. glauca (SGC) exhibited the highest cytotoxic potential, with an LC50 of 31.12 µg/mL. The present investigation examined the remarkable biological capabilities exhibited by S. glauca. Future research in therapeutic development could potentially be enhanced by the isolation and characterization of these bioactive compounds through further research.

Keywords

Phytochemical

Antioxidant

Cytotoxic

Phytotoxic

Antibacterial

Biopharmacological

1 Introduction

Throughout history, medicinal plants have been utilized to cure diseases, improve health, and foster wellbeing. The medicinal capabilities of the bioactive chemicals found in these plants make them significant resources for both conventional and contemporary medicine. Plants play a significant role in pharmaceutical research and development; around 25 % of prescribed medications worldwide are generated from them (Newman and Cragg, 2020; Ali et al., 2023). These systems acknowledge the benefits of using natural remedies as well as the holistic approach to healthcare. There exists a vast array of medicinal plants, several species of which have been investigated for their therapeutic use. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 80 % of individuals in developing countries get their basic medical needs from conventional herbal therapy (Ansari et al., 2023, Heise et al., 2023; Noreen et al., 2023). The use of medicinal plants in contemporary healthcare has become more popular recently. Numerous investigations are devoted to determining and evaluating the medicinal potentials of different plants, which results in the identification of novel bioactive substances and possible therapies (Abbasi et al., 2020; Ijaz et al., 2024a). Medical plants have significant potential for enhancing world health and offering accessible and cheap therapies for a variety of disorders as study into their advantages continues. Renala Khurd is an administrative division of the Okara district of Punjab with a total area of 230299 acres. Okara District is located on the Southern border of the Punjab, Pakistan (Board et al., 2017).

Setaria glauca (L), a fodder grass with rapid growth, may grow as tall as 1 m (Kalita et al., 2013). Plants are mature enough to generate seeds when they reach a height of 5 to 10 cm (Langille et al., 2001). S. glauca is a productive plant that is used to create herbal medicines. Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) may be made from S. glauca as well as several woody plants by the process of acid hydrolysis. In the pharmaceutical sector, microcrystalline cellulose is a drug delivery system. MCC and micro beads containing isoniazid, a TB antibacterial medication known as Nydrazid, have been used to treat the disease. That was the first medication in its class to get approval when intestinal fluid (artificial fluid used in therapeutic labs) was also present (Kalita et al., 2013). Yellow foxtail's vegetative tissues are used as food by animals, and several species of birds eat its seed. In India, the grains of S. glauca are used in a variety of culinary preparations, including boiling grain (anna), thin gruel (peja or ganji), porridge (sankati), and unleavened bread (roti). In the Indian town of Jalaripalli, S. glauca grains are used to make six different types of food (Kosma et al., 2004).

These systems acknowledge the benefits of using natural remedies as well as the holistic approach to healthcare. There exists a vast array of medicinal plants, several species of which have been investigated for their therapeutic use. For example, the WHO estimates that over 80 % of individuals in developing countries get their basic medical needs from conventional herbal therapy.

Research has focused on the identification of bioactive compounds and investigation of in vitro bioactivities of different Setaria glauca extracts (Tykhonova et al., 2021; Ijaz et al., 2023, 2024b). Overall, Setaria glauca exhibit medicinal potential, but further research is needed to fully understand its therapeutic potential. Through in vitro experiments, this work attempts to evaluate the possible biological activities of the bioactive chemicals found in S. glauca extracts in addition to identifying and characterizing them. We intend to open up new avenues for investigation into the therapeutic qualities of S. glauca and investigate its possible uses in the pharmaceutical and healthcare sectors by clarifying its bioactive profile and bioactivities. We hope that this study will shed light on the significance of traditional medicinal plants, such as S. glauca for drug development and discovery, highlighting their potential as a source of new therapeutic molecules.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 1. Collection of plants and preparation of plant extract

S. glauca (Acc. No. 130836) was gathered as an intact plant in the Renala Khurd, district of Okara, Punjab, Pakistan. The entire plant was harvested, thoroughly cleaned, shade-dried, and milled into a fine powder. The extraction technique involved the use of 30 g/300 mL of both polar (methanol) and nonpolar (chloroform). The ultimate blend was permitted to settle at ambient temperature for a duration of seven days prior to undergoing filtration. Subsequently, it was transferred into incubator shaker and agitated for a period of ten minutes at a speed of 200 rpm. The resulting filtrates were then stored at a temperature of 4 °C for future utilization, following concentration through employment of an evaporator (R-200 Buchi, Switzerland). For each plant extract, a 900 mL filtrate was obtained by repeating the entire process three times.

2.2 FTIR analysis

The Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was conducted using the Maitera and Chukkol technique as described by Maitera et al. (2016). Plant specimens weighing 0.5 mg were positioned on the diamond area of the spectrophotometer. The absorption spectra were produced utilizing wavenumbers ranging from 4000 to 400 cm−1 (Maitera et al., 2016).

2.3 Evaluation of antioxidant analysis

2.3.1 DPPH radical scavenging assay

Each plant sample (20 µL) to be tested was mixed with 180 µL of DPPH reagent in respective wells in order to attain the final volume of 200 µL. Ascorbic acid was taken as positive control while DMSO was used as negative control. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 25 °C in dark and absorbance was recorded at 517 nm employing microplate reader. DPPH free radical scavenging capability was calculated by formula below:

2.3.2 Total antioxidant capacity analysis

A 100 µL sample solution (of each plant) was mixed in 900 µL of reagent solution (4 mM ammonium molybdate, 0.6 M sulfuric acid and 28 mM sodium phosphate). The resulting mixture was incubated for 90 min at 95 °C and then mixture was cooled at room temperature. For the generation of calibration curves, varying concentrations of ascorbic acid were employed, alongside 100 µL of DMSO used the blank. The Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) was quantified by representing it as milligrams of ascorbic acid equivalent per gram of plant material. The data were illustrated as AAE by utilizing the calibration curve for ascorbic acid (y = 0.0001x + 0.3365) (Uchoa et al., 2015).

2.3.3 Total reducing power analysis

After adding 200 ml of 0.2 M phosphate buffer and 100 ml of 1 % potassium ferricyanide solution, the mixture was incubated at 50° C for 20 min. After that, it was subjected to a total reducing power test. After adding 200 L of trichloroacetic acid, the mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm. To acidify the reaction mixture, 150 mL of the supernatant layer was removed and combined with 50 mL of 0.1 mL sodium chloride solution. The results were expressed as milligrams of ascorbic acid per gram of plant extract, with gallic acid acting as the positive control (Ravisankar et al., 2014).

2.4 Antibacterial activity

Three bacterial strains (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus) that are resistant to multiple drugs were effectively inhibited by the antimicrobial activity. Additionally, five bacterial strains from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were also susceptible to the antimicrobial agent: L. monocytogenes (ATCC 13932), E. coli (ATCC 25922) S. aureus (ATCC 66332593), S. enterica (ATCC 14028), and P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853). The Quaid-e-Azam University in Islamabad's Department of Microbiology provided the bacterial strains. One liter of distilled water was added to the 28 g nutrient agar medium to bring its pH down to 6.5. Next, around 6 mm in diameter spherical discs were created using Whatman's filter paper #1. The sterile atmosphere was preserved. Poured into a Petri plate, the autoclaved medium was allowed to solidify. 1. The 5-liter sample solution and the 2.5-liter reference medication were applied onto filter paper discs let it dried, and then placed on petri plates containing nutritional agar medium and bacterial inoculums. Each plate was then put in an incubator at 37 °C for a complete day. After the incubation period, the clear zones of inhibition were precisely gauged using a Vernier caliper, and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by the broth microdilution technique (Moonmun et al., 2017).

2.4.1 Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and activity index (AI) determination

The plant extract's minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was assessed across six different dilutions (from 31.25 mg/mL to 1000 mg/mL) to evaluate its effectiveness against fungi. In the case of bacteria, both MIC and AI were calculated. However, the activity index was determined using the following formula:

2.5 Cytotoxicity assay

Artemia salina eggs were incubated in a divided hatching tray containing artificial seawater. The hatching process involved using a solution consisting of 3.8 g of sea salt dissolved in one liter of distilled water. The incubation period lasted for one to two days, resulting in the hatching of the eggs. Subsequently, 10 Nauplii were transferred into individual glass vials containing dried plant material and 5 mL of seawater. The experimental setup included a positive control group with nauplii, sea water, and vincristine sulfate in vials, as well as a negative control group with methanol, nauplii, and sea water. Following a 24-hour incubation period, each vial's dead nauplii count was noted, and the LC50 values were computed using three experiment repeats. Next, the death rate was contrasted with that of the group under positive control (Olowa et al., 2013).

2.6 Phytotoxicity assay

In order to accomplish this task, Petri plates that had been autoclaved were filled with Whatman filter paper #1 (sterile filter paper). After the sample solution was poured and allowed to evaporate, 5 mL of distilled water was added. Subsequently, the plates were sterilized for 50–60 s in a 1 % mercury chloride solution, and 15–20 radish seeds were placed and covered with parafilm. The Petri plates were then put in an incubator at 25 °C. After a period of 5 days, the percentage of germinated seeds was determined, and then root length was carefully documented. Following the repetition of the experiment three times, calculations were carried out (Ramalakshmi et al., 2013).

3 Results

Antioxidants, DPPH radical scavenging, TRP, TAC, antibacterial activity, cytotoxicity, and phytotoxicity of S. glauca were tested at six different dilutions. Both methanol and chloroform extracts were employed, with dilutions 1000 µg/mL to 31.25 µg/mL. The degrees of significance were indicated by A-N, A-L, A-G, and A-G at P < 0.05 (LSD). The data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Asterisks denoted significant differences (p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**. P < 0.001***) while NS represented non-significant (p < 0.05). The degree of freedom was represented by df. SGM: S. glauca methanol extract; SGC: S. glauca chloroform extract.

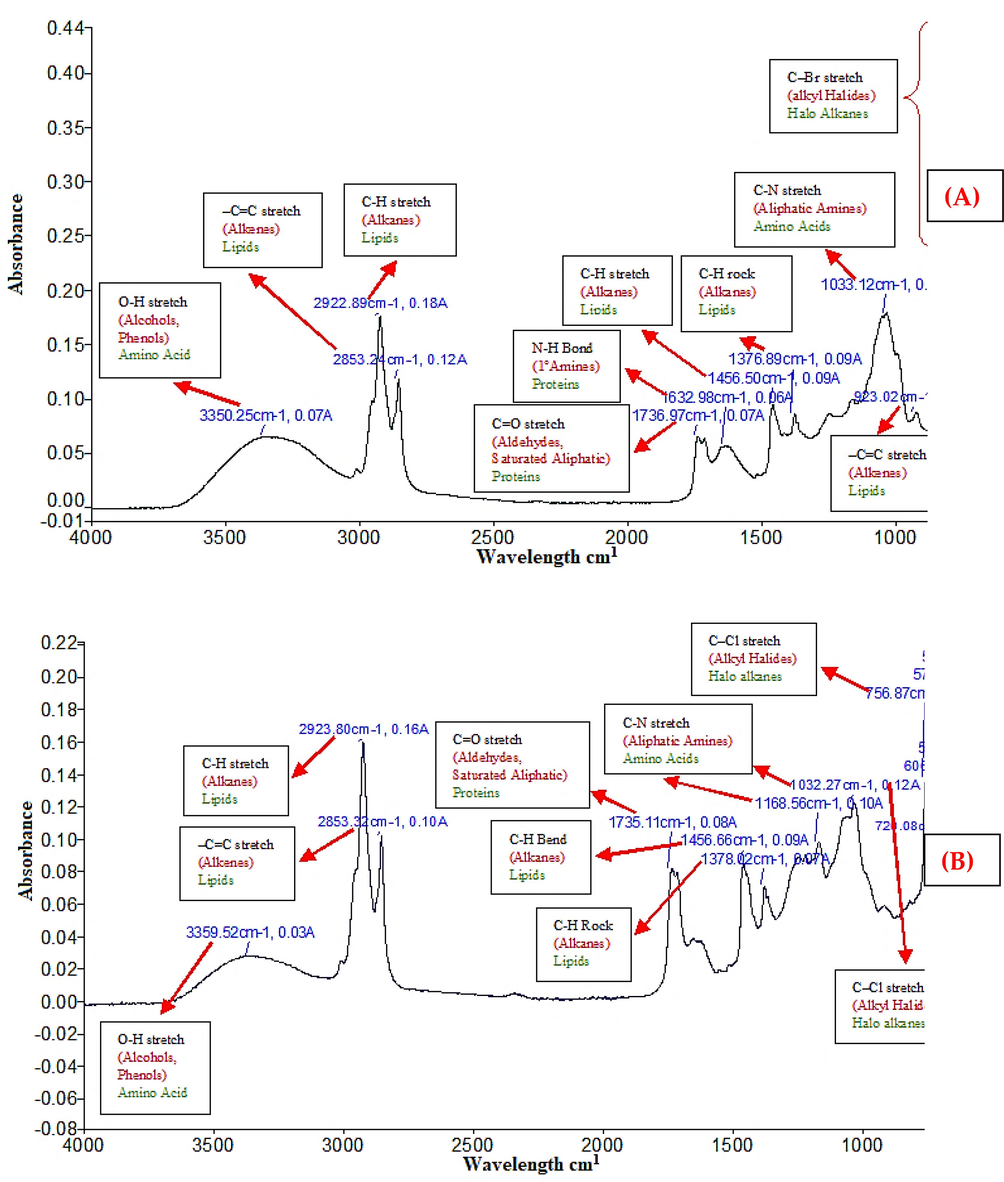

3.1 FTIR spectroscopy

The functional groups in SGM include O–H bonds (alcohols, phenols), =C–H stretches (alkenes), C–H stretches (alkanes), C–H bend (alkanes), N–H bends (1^amines), C = O stretches (aldehydes, saturated aliphatic), C-Br stretches (alkyl halides), C-N stretches (aliphatic amines), and = C–H bend (alkenes) (Fig. 1 A). The results of the SGC investigation revealed the indication of functional groups with the following names: C–H bend (alkanes), C–H stretch (alkanes), C–H rock (alkanes), C–H stretch (alkyl halides), C–N stretch (aliphatic amines), and C = O stretch (saturated aliphatic, aldehydes) (Fig. 1 B).

FTIR study of S. glauca (SGM) methanol extract and S. glauca (SGC) chloroform extract.

3.2 Antioxidant assays

The capacity of plants to scavenge ROS is part of their antioxidant potential. Plants have a built-in antioxidant capacity to scavenge ROS and shield cells from harm; otherwise, ROS would destroy cell function. Taking into account the above mentioned information, an antioxidant study using the DPPH test, TAC, and TRP was conducted to determine the antioxidant capacity of S. glauca.

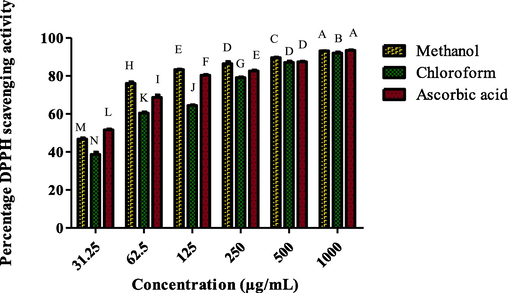

3.3 DPPH radical scavenging assay

The IC50 value of 28.38 ± 0.52 µg/mL is the smallest in SGM. SGC, on the other hand, displayed the highest IC50 value of 48.58 ± 2.10 µg/mL, with a % DPPH scavenging activity ranging from 38.73 ± 1.20 µg/mL to 92.04 ± 0.06 µg/mL (Fig. 2). As a reference, ascorbic acid showed a substantial IC50 value of 24.78 ± 1.13 µg/mL (Table 1).

S. glauca methanol and chloroform extracts' capacity to scavenge DPPH radicals at different dilutions.

Sr. No.

Plant Samples

IC50 (µg/mL)

1

SGM

28.39 ± 0.52D

2

SGC

48.58 ± 2.10B

3

Ascorbic acid

24.78 ± 1.13E

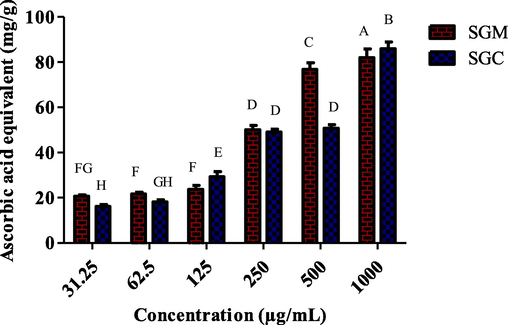

3.4 Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) analysis

The TAC of S. glauca was assessed by analyzing its methanol and chloroform extracts at six varying concentrations (1000 µg/mL to 31.25 µg/mL). Additionally, the TAC of each plant sample was determined by measuring the amount of ascorbic acid equivalent (mg/g) using the phosphomolybdate test (Fig. 3). The results indicated that SGC had the highest TAC value (16.11 ± 0.94 AAE/g to 85.95 ± 3.04 AAE/g), while SGM's methanol extract had the lowest value (20.7 ± 0.5 AAE/g to 82.03 ± 3.79 AAE/g).

1. Different dilutions were used to analyze the total antioxidant capacity of methanol and chloroform extracts of S. glauca.

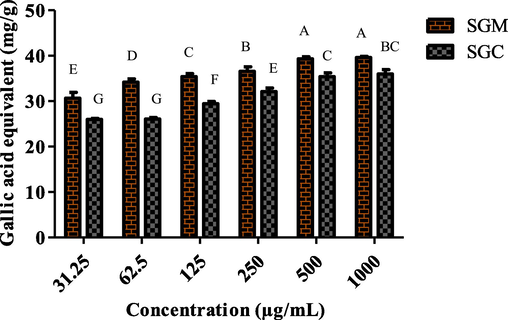

3.5 Total reducing power (TRP) analysis

Six different dilutions were prepared for both chloroform and methanol extracts, with concentrations 1000 µg/mL to 31.25 µg/mL, the total reducing power of S. glauca was evaluated. An increase in extract absorbance suggested a greater capacity to reduce ferric iron. SGM revealed 62.87 ± 0.73 GAE/g to 40 ± 0.59 GAE/g decreasing potential, while SGC represented 52.69 ± 2.68 GAE/g to 24.30 ± 0.61 GAE/g TRP values. It was noted that S. glauca extracts produced substantial effects (Fig. 4).

The TRP of different dilutions of methanol and chloroform extracts of S. glauca was determined.

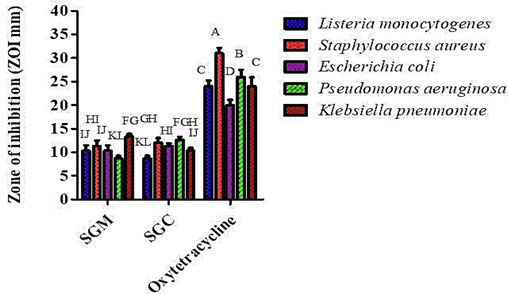

3.6 Antibacterial activity

The method of disc diffusion was employed to assess the antibacterial potential of S. glauca at five different concentrations (1000–62.5 µg/mL) for both chloroform and methanol extracts. Plant extracts were tested against one MDR strain (K. pneumoniae) and four ATCC strains (S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa). The findings showed that, in relation to every bacterial strain, every plant extract demonstrated resistance with varying degrees of inhibition (Fig. 5). On the other hand, oxytetracycline demonstrated ZOI against E. coli, K. pneumoniae (MDR), and L. monocytogenes of 20 mm, 24 mm, and 24 mm were the mean values respectively. Extracts with a zone of inhibition between 20 and 25 mm exhibited a minimum inhibitory concentration of 10 µg/mL; similarly, extracts with a ZOI between 15 and 20 mm showed a MIC of 50 µg/mL, and extracts with a ZOI between 10 and 15 mm showed a MIC of 50 µg/mL. The highest ZOI (13.33 ± 0.57 mm mean value) against K. pneumoniae (MDR) was seen in the methanol extract of S. glauca, whereas the inhibition zone (mean value) against S. aureus was 11.33 ± 1.15 mm. SGM demonstrated a ZOI of 10.33 ± 1.15 mm against L. monocytogenes, however the lowest ZOI (mean value) of 8.66 ± 0.5 mm was seen against P. aeruginosa. When SGC was used against P. aeruginosa, the highest zone of inhibition was found to be 12 ± 1.0 the mean value. The results of SGC analysis showed that the ZOI against P. aeruginosa was 12.66 ± 0.56, while the ZOI against S. aureus was 12 ± 1 mean value. The ZOI against E. coli was 11.33 ± 0.57 mm, and the ZOI against K. pneumoniae was 10.33 ± 0.57 mm. SGC produced the smallest zone of inhibition (ZOI) at 8.66 ± 0.5 mm (mean value) for P. aeruginosa. On the other hand, oxytetracycline, utilized as a positive control, exhibited a maximum ZOI of 36 mm (mean value) for S. aureus and 26 mm (mean value) for P. aeruginosa. Oxytetracycline was compared to a regular medication as its positive control, while DMSO used as the negative control with no zone of inhibition observed. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each plant extract was determined in comparison to five bacterial strains (Table 2). Key: S. glauca methanol extract; SGC: S. glauca chloroform extract; ATCC: American type culture collection; MDR: Multi drug resistant: MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration.

S. glauca extracts in methanol and chloroform have antibacterial activity at different dilutions, along with standard (oxytetracycline).

Sr. No.

Bacterial Strains

SGM

MIC (µg/mL)

SGC

MIC (µg/mL)

Oxytetracycline

MIC (µg/mL)

1

L. monocytogenes (ATCC)

50

−

25

2

S. aureus (ATCC)

50

50

10

3

E. coli (ATCC)

50

50

25

4

K. pneumoniae (MDR)

50

50

50

5

P. aeruginosa (ATCC)

−

50

50

3.7 Cytotoxicity assay

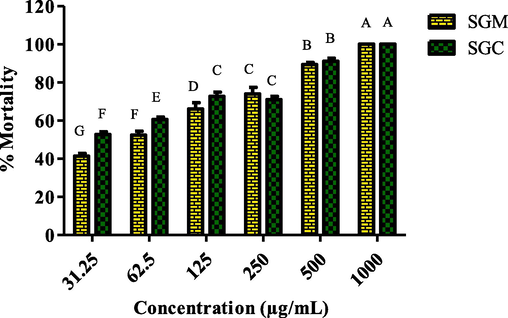

The lethality experiment with brine shrimp was employed to assess the cytotoxicity of plant extracts. There were six different S. glauca dilutions employed, 1000 µg/mL to 31.25 µg/mL (Fig. 6). The effects demonstrated a strong correlation between plant extracts' cytotoxic potency and dilutions. Additionally, the tested samples' LC50 values were computed (Table 3). With the lowest LC50 value of 31.12 ± 1.43 µg/mL among the four plant extracts, SGC produced the best results (Fig. 6), followed by SGM at 53.40 ± 0.80 µg/mL. The cytotoxic potential of chloroform extract is greater than that of polar solvents. Vincristine sulphate was employed as a positive control at 0.64 ± 0.04 µg/mL.

Cytotoxicity of S. glauca extracts in methanol and chloroform at different dilutions.

Sr. No.

Plant Samples

LC50 (µg/mL)

3

SGM

53.40 ± 0.80A

4

SGC

31.12 ± 1.43B

5

Vincristine sulphate

0.64 ± 0.04C

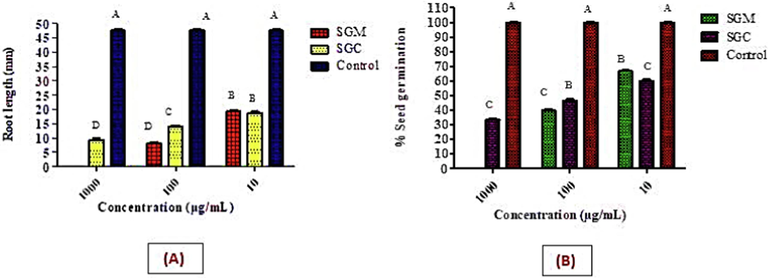

3.8 Phytotoxicity assay

Allelopathy, also known as phytotoxicity, is the inhibition of growth and development caused by various toxins released by neighboring plants. In the radish seed germination study, the phytotoxic effects of S. glauca were assessed at three varied concentrations: 1000 µg/mL, 100 µg/mL, and 10 µg/mL. After a 5-day incubation period, the current study measured the minimum percentage of germination in the seeds and the minimum length of the roots. When compared to other extracts, it was found that SGM produced the greatest outcomes by decreasing both the percentage of seed germination and the length of the roots (Fig. 7A). Additionally, SGC's phytotoxicity was assessed, with notable outcomes. As a control, water demonstrated the highest percentage of seed germination as well as the longest root lengths (Fig. 7B).

Phytotoxic effect of methanol and chloroform extracts of S. glauca on the percentage germination of radish seeds at different dilutions.

4 Discussion

The objective of the present investigation was to report on the various therapeutic potential of S. glauca. As far as we know, this is the first analysis of S. glauca's biological activities, including cytotoxicity, phytotoxicity, and antibacterial activity, as well as antioxidant tests (DPPH, TAC, TRP, and FTIR). Phytochemical study of S. glauca revealed the TPC of 89.17 ± 0.53 mg GAE/mg in methanol extract and minimum in chloroform extract 152.41 ± 1.70 GAE mg/g. Previously authors (Goudar et al., 2016; Chandrasekara et al., 2012; Butnariu et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2013) stated the TPC in plants of same genus Setaria (S. italica, S. viridis and S. italica) and results are in line with the findings i.e. TPC = 57.17 ± 0.78 mg GAE/100 in aqueous extract. In present work, the TFC revealed by S. glauca was maximum in chloroform extract (25.70 ± 1.63 QE mg/g) and minimum in methanol extract (13.61 ± 1.60 QE mg/g). These findings are also correlated with the work of Sharma et al. (Sharma et al., 2015) mentioning that the TFC values ranged from 28.1 ± 0.19 mg RU/g in S. italica. Hence it can be concluded that the selected plants with significant phenolic and flavonoid contents which contribute to different biological purposes. The idea that a large proportion of bioactive chemicals are present in plants is supported by FTIR spectroscopy. Plants have a variety of phytochemical classes, as demonstrated by the functional groups that were recognized using the FTIR analysis. The S. glauca extracts were also found to include the functional groups C–H, N–H, C-N, =C–H, C = O, O–H, and −C-Br in the current investigation. Similar reports (Stroescu et al., 2013; Ashokkumar et al., 2014; Nagarajan et al., 2017) are available in literature in which authors reported different functional groups in some medicinal plants.

Methanol extracts shown considerable promise for DPPH antioxidant action. Our results show that S. glauca methanol extract has a greater potential for antioxidants, with an IC50 value of 28.38 ± 0.52 µg/mL. Suma and Urooj described similar outcomes (Suma et al., 2012) mentioning that the S. italica methanol extract showed significant DPPH radical scavenging potential as compared to other solvents (chloroform and ethanol). Our findings correlate with the findings of Amadou et al. (Amadou et al., 2013) and Sharma et al. (Sharma et al., 2015) indicating the percentage free radical scavenging activity (62.45 % to 90.54 % to 85.28 ± 2.06 mg/mL) of S. italica aqueous extract. In this investigation, the chloroform extract of S. glauca with an IC50 of 48.58 ± 2.10 g/mL demonstrated strong DPPH free radical scavenging capacity. Plants with minimum IC50 values are the potential target for the synthesis of antioxidant medications, and they have a significant impect in the pharmaceutical sector. The antioxidant capacity of each selected plant extract was assessed using the TAC (phosphomolybdenum test). In the present study, the highest TAC value of S. glauca was found in its chloroform extract, which was 85.95 ± 3.04 mg AAE/g. Its methanol extract had a TAC value of 82.03 ± 3.79 mg AAE/g. Previously, Asharani et al. (Asharani et al., 2010) observed the TAC of S. italica ranged from 5.7 mM TE/g to 4.4 mM TE/g which has been correlated in the present study.

One method for measuring antioxidants is the FRAP test. Antioxidant capacity and reducing power of a plant are connected (Dorman et al., 2003). and the stronger the antioxidant activity, the higher the reducing power (Guo et al., 2016). S. glauca methanol extract depicted maximum TRP value of 39.58 ± 0.26 GAE mg/g. Our findings also correlate with the work of Suma and Urooj (Suma et al., 2012) describing that the methanol extracts revealed maximum TRP in S. italica. In the current study, non-polar solvent extracts also showed remarkable antioxidant potential. Therefore, it is possible that certain plant extracts might be employed in the food industry as antioxidants and in the pharmaceutical industry to treat a variety of illnesses. The available data also demonstrated that, when it came to main antibacterial activity against five different bacterial strains, the methanol extracts outperformed the other extract. In a separate investigation, the methanol extract of S. glauca shown the highest ZOI (13.33 mm) against K. pneumoniae, while the chloroform extract had noteworthy efficacy against several types of bacteria. Our findings are parallel to the report of Peksel et al. (Peksel et al., 2006) in which author mentioned that S. italica exhibited strong antibacterial potential against E. coli (16.27 ± 0.34 mm) and S. aureus (14.17 ± 0.42 mm).

Cytotoxicity is one of the in vitro biological screening methods employed to assess extracts during the drug-discovery process. We confirmed the presence of both anticancer and pesticidal chemicals using the brine shrimp mortality assay. The chloroform extract of S. glauca showed a minimum LC50 value of 31.12 ± 1.43 µg/mL in the current investigation. S. glauca methanol extract produced impressive LC50 values with excellent lethality potential, suggesting that the chosen plant can be utilized to create anticancer medications. The genuine approach to identifying the bioactive chemicals found in plants is the brine shrimp lethality evaluation (Ullah et al., 2013). Plants exhibit allelopathic capabilities owing to the existence of distinct biochemicals known as allelochemicals. These allelochemicals exert a wide range of impacts on organisms, affecting their ability to germinate, survive, grow, and reproduce through a multitude of mechanisms (Latif, et al., 2017). The phytotoxic potential of specific plants was assessed using the radish seed assay. The methanol extracts exhibited the shortest root length and the highest percentage of seed inhibition, followed by the chloroform extracts, as indicated by the findings. The toxicity level of medicinal plants was found to escalate with increasing concentration (Gilani et al., 2010). Based on the correlation found in the recent study, it was observed that the methanol extracts of S. glauca showed the lowest level of inhibition on seed germination at a concentration of 10 µg/mL. However, as the concentration increased from 10 µg/mL to 1000 µg/mL, the toxicity of these plants completely prevented seed germination. This suggests that plants with strong allelopathic potential could be utilized as a viable strategy for biological weed management (Mahajan et al., 2013).

4.1 Statistics

The experiments were carried out three times, and the mean ± standard deviation was calculated using Microsoft Excel version 2016. ANOVA was employed in Statistical version 8.1 to assess the results of the antioxidant analysis, biological evaluation, and phytochemical analysis. LSD was used to determine the significant level. The LC50 value was calculated using the Finney, 1952 Probit analysis tool, while the IC50 value was estimated using Graph Prism version 5.01.

5 Conclusion

The ability of S. galuca, a plant well-known for its therapeutic characteristics, to cure a wide range of illnesses has long been appreciated. Strong bioactive compounds that have beneficial therapeutic properties are suggested by the traditional folk medical usage of S. galuca. The phytochemical and biological characteristics of S. galuca was not well explored priviously, despite its popularity in traditional medicine. In current study the biological and phytochemical potential of methanol as well as chloroform extracts of S. galuca have been documented. Research is being done on the phytochemicals that have been taken out of these medicinal plants because they have been used as a source for already commercialized drugs. The findings from antioxidant tests conducted on S. galuca extracts indicate that the Chloroform extract of S. galuca shows promising potential in mitigating oxidative stress and can be consequently used as a potential target for the innocuous production of natural medicines in pharmaceutical industry. The FTIR analysis revealed the presence of several classes of phytochemicals which are responsible for their phytochemical and biological activities. Chloroform extract of S. galuca exhibited significant antioxidant potential as well as cytotoxic potential. The present research indicates that antioxidant, antibacterial, cytotoxic, and phytotoxic tests provide scientific foundations and explore various aspects of medicinal plants that are crucial in defense mechanisms and can combat pathogens effectively. Overall, Setaria glauca exhibit medicinal potential, but further research is needed to fully understand its therapeutic potential.

6 Consent for publication

All authors consent to publish this manuscript in Journal of King Saud University – Science.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shumaila Ijaz: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Javed Iqbal: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Conceptualization. Banzeer Ahsan Abbasi: Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal analysis. Sobia Kanwal: Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal analysis. Mahboobeh Mahmoodi: Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal analysis. Mohammad Raish: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Tariq Mahmood: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSPD2024R957) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Green formulation and chemical characterizations of Rhamnella gilgitica aqueous leaves extract conjugated NiONPs and their multiple therapeutic properties. J. Mol. Struct.. 2020;1218:128490

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethnomedicinal plant use value in Lower Swat, Pakistan. Ethnobot. Res. Appl.. 2023;25:1-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antimicrobial, antioxidant activities, and nutritional values of fermented foxtail millet extracts by Lactobacillus paracasei Fn032. Int. J. Food Prop.. 2013;16(6):1179-1190.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, M. K. A., Iqbal, M., Chaachouay, N., Ansari, A. A., and Owens, G. (2023). The Concept and Status of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Plants as Medicine and Aromatics: Pharmacognosy, Ecology and Conservation, 129.

- Natural antioxidants in edible flours of selected small millets. Int. J. Food Prop.. 2010;13(1):41-50.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening by FTIR spectroscopic analysis of leaf extracts of selected Indian medicinal plants. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci.. 2014;3(1):395-406.

- [Google Scholar]

- Board, Y. P. (2017). Annual Report 2016-17.

- Butnariu, M., Bostan, C., and Samfira, I. Determination of mineral contents and antioxidant activity in some plants that contain allelochemicals of Banat region (Western Romania). Studia Universitatis“ Vasile Goldis” Arad. Seria Stiintele Vietii (Life Sciences Series). 2012, 22(1), 95.

- Effect of processing on the antioxidant activity of millet grains. Food Chem.. 2012;133(1):1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterisation of the antioxidant properties of de-odourised aqueous extracts from selected Lamiaceae herbs. Food Chem.. 2003;83(2):255-262.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytotoxic studies of medicinal plant species of Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot.. 2010;42(2):987-996.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of processing on ferulic acid content in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) grain cultivars evaluated by HPTLC. Orient J Chem.. 2016;32(4):2251-2258.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant efficacy of rosemary ethanol extract in palm oil during frying and accelerated storage. Ind. Crop. Prod.. 2016;2016(94):82-88.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heise, T., Villar-Lopez, M., and Salaverry, O. (2023). Person-centered traditional medicine. In Person Centered Medicine (pp. 665-684). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Ijaz, S., Iqbal, J., Abbasi, B. A., Kanwal, S., Tavafoghi, M., Ahmed, M. Z., & Mahmood, T. (2024a). Investigation of bioactive constituents and evaluation of different in vitro antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity potentials of different Portulacaria afra extracts. Journal of King Saud University-Science, 2024a, 36(2), 103033.

- Ijaz, S., Iqbal, J., Abbasi, B. A., Tufail, A., Yaseen, T., Uddin, S., & Sharifi‐Rad, J. (2024b). Current stage of preclinical and clinical development of guggulsterone in cancers: Challenges and promises. Cell Biology International, 2024b, 48(2), 128-142.

- Rosmarinic acid and its derivatives: Current insights on anticancer potential and other biomedical applications. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2023;162:114687

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraction and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from fodder grass; Setaria glauca (L) P. Beauv, and its potential as a drug delivery vehicle for isoniazid, a first line antituberculosis drug. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces. 2013;108:85-89.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cadmium bioaccumulation in yellow foxtail (Setaria glauca LP Beauv): Impact on seed head morphology. Am. J. Undergrad. Res.. 2004;3(1):9-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Langille, P. D. Selectivity of nicosulfuron on Setaria glauca (L.) Beauv. and Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv. Publication Information (1). 2001. https://hdl.handle.net/10214/23564.

- Latif, S., Chiapusio, G., and Weston, L. A. Allelopathy and the role of allelochemicals in plant defence. In Advances in botanical research. 2017, Vol. 82, pp. 19-54. Academic Press. doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2016.12.001.

- The role of cultivars in managing weeds in dry-seeded rice production systems. Crop Prot.. 2013;49:52-57.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical and fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis of Faidherbia Albida (Del) as a preservative agent. World J. Res. Rev.. 2016;3(3):25-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative phytochemical estimation and evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activity of methanol and ethanol extracts of heliconia rostrata. Indian J. Pharm. Sci.. 2017;79(1):79-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis of garlic (Allium) Int. J. Zool. Stud.. 2017;2(6):11-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod.. 2020;83(3):770-803.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological and molecular characterizations of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and their influence on soil physicochemical properties and plant nutrition. ACS Omega. 2023;8(36):32468-32482.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brine shrimp lethality assay of the ethanolic extracts of three selected species of medicinal plants from Iligan City, Philippines. Mortality. 2013;1(T2):T3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxident activities of aqueous extracts of Purslane (Portulaca oleracea subsp. Sativa l.) Italian J. Food Sci.. 2006;18(3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on cytotoxic, phytotoxic and volatile profile of the bark extract of the medicinal plant, Mallotus tetracoccus (Roxb.) Kurz. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2013;12(43):6176-6184.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activites and phytochemical analysis of methanol extract of leaves of Hypericum hookerianum. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2014;6(4):456-460.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity, total phenolics, flavonoids and antinutritional characteristics of germinated foxtail millet (Setaria italica) Cogent Food Agric.. 2015;1(1):1081728.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of fatty acids extraction from Portulaca oleracea seed using response surface methodology. Ind. Crop. Prod.. 2013;43:405-411.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of extracts from foxtail millet (Setaria italica) J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2012;49(4):500-504.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of Setaria glauca (L.) p. beauv. population’s vital parameters in grain agrophytocenoses. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag.. 2021;77(1):36-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity and phytochemical profile of Spondias tuberosa Arruda leaves extracts. Am. J. Plant Sci.. 2015;6(19):3038.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti–bacterial activity and brine shrimp lethality bioassay of methanolic extracts of fourteen different edible vegetables from Bangladesh. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed.. 2013;3(1):1-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103321.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: