Translate this page into:

Instrumental insemination: A nontraditional technique to produce superior quality honey bee (Apis mellifera) queens

⁎Corresponding author at: Unit of Bee Research and Honey Production, Biology Departement, Faculty of Science, P.O. Box 9004, Abha 61413, Saudi Arabia. khalidtalpur@hotmail.com (Khalid Ali Khan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Honey bee queen serves as a colony's centre hub, producing eggs and releasing pheromones to keep a colony together. Artificial insemination in Apis mellifera, trending research these days, is a consistent method for controlling mating in honey bees. Quality queen production is essential to maintaining a healthy bee colony. A review of comparative studies on superior quality honey bee (A. mellifera) queens production through nontraditional techniques and various factors affecting the instrumental insemination process has been compiled in this article. Several factors like; rearing conditions, stress, inseminator’s skills, food availability, mating age of queen, queen banking, temperature, sperms stored in the spermatheca, sperms quality and quantity, semen handling and storage, CO2 and nitrogen treatments, pheromones affect the performance of instrumentally inseminated queens. Moreover, different data collection showed that different methods used for queen treatment which have a significant effect on the performance of the queen. This review suggested that artificially inseminated queens could be more productive if experiments were done with proper attention and precision.

Keywords

Apis mellifera

Queen

Artificial insemination

Superior quality

Drone

Various factors

1 Introduction

Honey bees' natural mating system is highly polyandrous (Gençer et al., 2014; Rousseau et al., 2015). Honey bee queen naturally mates in flight with 6–18 (Gençer and Kahya, 2011), 10 to 20 (Cobey et al., 2013), 15–20 drones (Cobey, 2016), by taking one or two mating flights (Hasnat, 2018) in the congregation area of the drones where approximately 10,000–30,000 drones are present from different genetic sources (Cobey, 2016). This is the unique behavior of the European honey bee queen in all domestic animals (Rousseau et al., 2015; Hasnat, 2018).

Artificial insemination (also called control mating) is an important tool for A. mellifera breeding in which semen is collected from the selected drone(s); this mixture can be used to inseminate a large group of queens (Van Praagh et al., 2014). Artificial insemination in honey bee queens (A. mellifera) started in the 1920s, first depicted in the 1940s (Prodělalová et al., 2019) and in the 1950′s (Cobey, 2007). This practice is more common in Poland, in which annually 50,000 to 90,000 queen bees are inseminated, while in the rest of the world, only 6000 to 10,000 queens are artificially inseminated (Gąbka and Cobey, 2018). In honey bee queens, artificial insemination has become a routine practice which conquers all problems that occur in natural mating (Pieplow et al., 2017; Abou-Shaara et al., 2021). Artificial insemination is a well-organized method of reproduction for control mating and selecting the best quality traits (Hasnat, 2018). Through artificial insemination colonies with desirable traits (like pollen hoarding, Varroa mite resistance, hygienic behaviors) can be produced (Huang et al., 2009; Khan and Ghramh, 2021). This is also an important tool for the genetic control of honey bees and widely used in research purposes from about last 70 years (Cobey et al., 2013; Cobey, 2016).

To attain their selection goals, beekeepers mix a queen with drones from a single 'father' lineage (Pieplow et al., 2017). Artificial insemination is a consistent method for breeding and to control random mating of honey bees but till semen storage for a long time (more than two weeks) remains impossible (Cobey, 2016).

The primary objective of this paper is to review the comparative study of naturally mated and artificially inseminated A.mellifera L. queen from 1946 to the present date. In addition, to demonstrate the factors which affecting the performance of instrumentally inseminated queens; rearing conditions, stress, inseminator’s skills, food availability, mating age of queen, queen banking, temperature, sperms stored in the spermatheca, sperms quality and quantity, semen handling and storage, CO2 and nitrogen treatments, and pheromones.

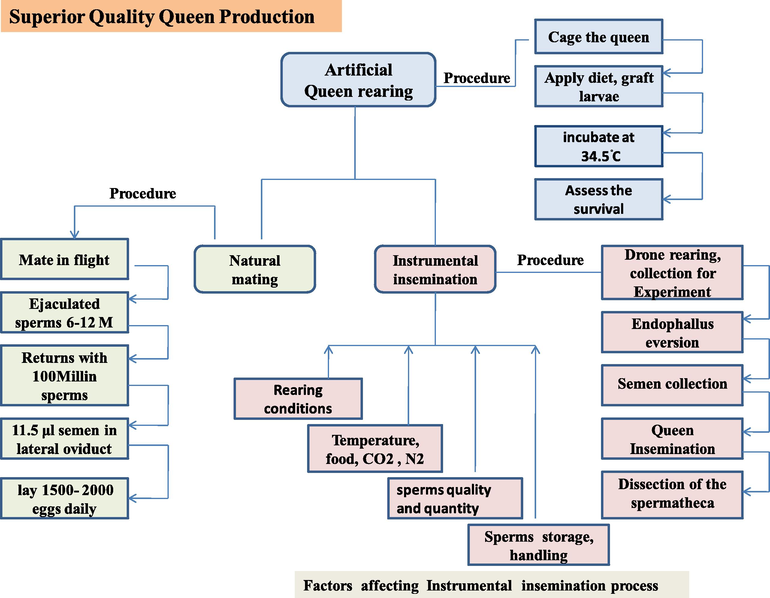

2 Superior quality queen bees production

Quality queen bees production is a trending research in these days. Queen rearing is very important to replace of failed queen from colony where it is very necessary. In this practice, first the queen is artificially reared in the laboratory and then kept in the colony to mate naturally or inseminated artificially by the selected breed strain.

2.1 Artificial queen rearing

Artificial queen rearing is very important practice because replacements of mated queen in colony reduce the gap between the eggs not laid and the production of new bees. Therefore, this process has refigured beekeeping industry (Contreras-Martinez et al., 2017). There are many factors which can affect queen quality; origin of larvae, age of the grafted larvae, number of nurse bees, food availability for the colony, and the number of drones queen mates. All the qualities of the colony depend on the queen's characteristics (Mahbobi et al., 2012).

The fecundity of the queen decrease after the first year of her age so requeening is very important to maintain a healthy colony because queen failure may lead to direct colon loss (Contreras-Martinez et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2021b). There are some parameters for the high-quality queen; high brood production, good hygienic behavior, high pollen production, low swarming tendency, high honey yield, calmness, high disease resistance (Hatjina et al., 2014). Productivity, swarming, disease resistance calmness or aggressiveness, development of the colony depends upon the genetic origin of the queen and the drone (with which she mates) (Hatjina et al., 2014).

In-vitro mostly-two rearing methods are used, in the first rear one larva in each cup and fed on daily basis according to need (Crailsheim et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2021a), which is about 160 µL in the entire larval developmental period (Aupinel et al., 2005). In the second method, provide the excess diet and transfer the larva to new dish frequently (Crailsheim et al., 2013). Diploid larvae that fed by the royal jelly rich in protein destined to queen (either by grafting method or natural rearing) (Hasnat, 2018).

Queen is caged in the empty brood comb for oviposition, which is confirmed after 72 h. Sterile the lab environment to avoid bacterial and fungal infections and prepare the diet as sugar solution with royal jelly in the ratio of 1:1 (w/w). Apply diets and graft the larvae into the cups (maintain temperature during grafting). Ingredients in the royal jelly (lipid, protein and sugar) of the worker and the queen larvae remain the same. If the sugar is added up with the juvenile hormone, larvae are determined to a queen. Incubate the larvae at 34.5 °C at relative humidity 95 % for six days and 80 % at day seven. Assess the survival of the larvae and remove the dead larvae from the incubator to prevent decay and contamination. Capping the rearing plates by beeswax and rotating vertically at day 11. Evaluate the rearing success by comparison with sister bees naturally rear in the colony (Crailsheim et al., 2013).

After the queen rearing, the queen is specified to the colony and allowed to naturally mate with the drones or artificially inseminated in the laboratory.

2.2 Natural mating

Drones mating with queen occurs very quickly. Each drone, during mating, ejaculates the sperms of about 6–12 million. A very small part of the sperms transfer to spermatheca, and the remaining hoard in the lateral oviduct of the queen. At the last mating with the drone, part of the reproductive organ shows the mating sign (Buescu et al., 2015).

After mating queen returns to the colony with the 100 million sperms in her genital tract and about 11.5 μL of semen in her lateral oviduct (Gençer et al., 2014). After this entire process of mating, ovaries become activated, and the queen starts to lay eggs about 1,500 per day (Kocher et al., 2010).

2.3 Artificial insemination

Select the healthy drones for the semen collection and healthy queens for the artificial insemination from the best hive (and use the drone after transfer within 30 min; if not, the drone’s physical cooling makes this task impossible) (Stoian et al., 2018).

Drones could be collected instantly after development (keep them in drone cages in bank colony) or mature drones on the day of insemination. Semen is collected from the mature drones by the eversion of endophallus. This eversion by hand occurs such as partial and complete eversion. Take a few seconds for the eversion of endophallus, maturity evaluation, and sperm quality determination. As the drone does not have sufficient semen (∼1 µL) or evert properly should be rejected. Have a great supply of mature drones (>need) because not all drones will yield semen. Avoid to touching the endophallus with fingers. Also, maintain the warm condition by the light above the flying box and feed well (a piece of honeycomb or bee candy) to expand their movement before use (Cobey et al., 2013). If the drone is mature, the abdomen will be hard in touch and cornua (a pair of horn-like structures) will be yellow-orange, and if the drone is immature, the abdomen will be soft and cornua will lack color (Cobey, 2016).

Semen is collected in a syringe from many drones and stored in a capillary glass tube (avoid containing air bubbles and extra saline with semen). Keep the syringe tip moist with the saline to avoid dryness; if exposed to air, sperms will dry very quickly. Semen collected from each drone about 1 µL and ∼ 8 to 12 µL is the standard volume to inseminate a queen. Maintain the sanitary conditions as mostly drones defecate during this process (but if the queen defecates during insemination discard the queen) and keep the alcohol-soaked towel for cleaning (Cobey et al., 2013).

Queen is inseminated during 5 to 12 days after emergence. Use CO2 treatment to anesthetize (Cobey et al., 2013) and neurosecretory production of the juvenile hormone that triggers the oviposition in the queen (Cobey, 2007). Usually, two treatments of CO2 are required; the first one or two days before the insemination and the second during the insemination. Cage the queen cells or use the queen excluder if use the mating nuclei to avoid the natural mating of the queen. Delivers the standard volume (is 8 to 12 µL) of semen into the oviduct and releases the queen into the mating nucleus to encourage sperm migration. The process of semen insertion should be completed in very short time (in seconds) for each queen. After the insemination, take the queen in the cage from the holder and release to her nucleus colony (Cobey et al., 2013).

The success of insemination can be checked out by the dissection of spermatheca 40 h after the insemination (about 40 h are required for the sperm migration after insemination). Before dissection, queens can be detained in nursery colonies. For dissection, first crush the head and thorax of the queen and then dissect the abdomen of the queen. The success of the insemination depends on the shade, color, and density of the spermatheca. The creamy tan color of the spermatheca shows the full insemination while the milky appearance shows the failed queen and if the spermatheca is clear, it shows the queen is a virgin (Cobey et al., 2013).

After the procedure of insemination, queens are mostly kept in queen cages with the low number of workers or sometimes in nursery colonies without workers. The complete procedure of insemination requires full attention, care, and accuracy for better results (Cobey, 2016).

3 Comparative study of naturally mated and artificially inseminated queens

Comparative studies about the performance of artificially inseminated and naturally mated queens have been started since 1900 s. Queen quality and performance of the queen could be estimated by the colony productivity, queen survival, quality, and onset of oviposition. Various studies have been compared with the performance of the naturally mated queen (NMQs) and artificially inseminated queen (AIQs). Most of the studies illustrate that artificially inseminated queens are more productive than naturally mated queens and some studies show the equal performance of both naturally mated and artificially inseminated queens (see Table 1).

Naturally mated queens (NMQs)

Artificially inseminated queens (AIQS)

Studies reported by

No. of NMQs

Colony productivity

Queen survival

Oviposition. Time & %

No. of AIQs

Colony productivity

Queen survival

Oviposition Time & %

Treatments

43

52.6 kg honey

65

95.3 kg honey

3x2.5 µL semen

(Roberts, 1946)

72

39 kg honey

15

54 kg honey

Woyke & (Ruttner, 1976)

1483

8 % less

58 % 1 Y 15 % 2 Y

672

50 % 1 Y, 27 % 2 Y.

(Vesely, 1984)

9

18,343 cells

2 Y

16

18,963 cells

2 Y

8 µL semen age 7–10 days

(Wilde, 1987)

10

21,817 cells

23

34,413 cells

20

2303 cm3

3998

cm3

19

2074 cm34145 cm3

Age 6–10 days 8 µL semen

Nelson & Laidlaw, 1988

12

8.6 Fr10.7 Fr

14

8.8 Fr10.4 Fr

Cobey, 1998

1114

38.0 kg

1105

37.9 kg

(Pritsch and Bienefeld, 2002)

2025

37.0 kg

1656

37.4 kg

1289

2.9 % in 5 days,

67.7 % in 6 to 10 days, 90.4 % in 15 days5 to 12 days

Skowronek et al., 2002

137

19.4 kg

612

21.3 kg

Age 7–8 days,Sem.12 µL

Cermak, 2004

50

233

Age 7–8 days Semen 12 µL

Equal survive

Equal survive

97 %

8 µL Semen with 6 min CO2 treat

Gerula et al., 2011

3.1 Colony productivity

Colony productivity depends on the productive queen. Numerous studies have compared the performance of NMQs and AIQs by weight of the queen, brood, and honey yield.

In the comparative studies of Roberts (1946) reported that colonies of NMQs showed low production of honey and credited the best performance of AIQs. A study reviewed in the 1970s stated that colonies have the instrumentally inseminated showed the the highest productivity. Another result was reported by Ruttner (1976) that colonies headed by AIQs showed high productivity at Apicultural Research Institute in Oberursel, Germany. According to the study of (Nelson & Laidlaw, 1988), there is no difference between productivity of AIQs and NMQs. Colony headed by AIQs produces more honey than NMQs about an average of 8%–12% (Vesely, 1984). In Germany at the Central Breeding Evaluation Program reported that AIQ shows equal or higher productivity (Pritsch and Bienefeld, 2002). Recently, the bee research institutes presented a report that there is no difference in the performance of NMQs and AIQs (Cobey, 2007). Colonies headed by AIQs of A. mellifera showed more productivity than the colonies headed by the NMQs (Pritsch and Bienefeld, 2002; Hasnat, 2018; Shawer et al., 2021). Remarkably, most of the studies presented that colonies headed by the AIQs illustrated high production (Cobey, 2007).

Artificial insemination also has disadvantages, like loss of genetic variability and change in worker behavior. To avoid these disadvantages, it is suggested to inseminate the queen by the semen of drones collected from different lines. Inbreeding problems can be avoided by avoid the unidirectional selection of drones (Pieplow et al., 2017).

Cobey (1998) observed the weight of the colony and brood area over two seasons in Ohio, USA, and stated that there is no difference in the productivity of AIQs and NMQs. In addition, Cobey (2007) reviewed a study that AIQs have a propensity to ascertain colonies, and have the potential to high brood production and high honey yield as compared to NMQs. But the pheromone production occurs later in AIQs, which affects the acceptance of the queen in the colony. AIQs have the same brood production as occurs in NMQs, but the honey yield was high in AIQs as compared to NMQs (Cobey, 2007).

3.2 Queen survival

Queen must have enough time for breeding. Many studies have compared the age of NMQs and AIQs. Otten et al. (1998) observed 522 AIQs in Germany and reported that age and time of insemination affect the achievement of the insemination procedure. The success rate of insemination procedure was 95 %, 82 %, and 80 % in the queens which were inseminated at the age of 10 days, 7 days, and 13 days old post-emergence, respectively.

The survival of the queen in any colony is strongly reliant on the number of sperms in spermatheca obtained either through natural mating or artificial insemination. As the queen ages, number of sperms decrease, the queen is replaced by a new queen. Rousseau et al. (2015) from North America reported that decrease of sperms observed in the young queens cause the replacement of queens in the colony. This decrease in sperm may be due to the infertility of drones. Data were presented by Cermak (2004) from Czech Republic, which shows that both NMQs and AIQs show higher survival rate. Cobey (1998) reported that both NMQs and AIQs have the same survival rate an average of 18 months in Ohio, USA. Some other studies also show that there is no difference in the survival of NMQs and AIQs.

In addition, most of the studies reported that there is no significant difference in the age and survival rate of the NMQs and AIQs (Cobey, 2007). The suitable age of the queen is very important to maintain for the artificial insemination procedure. Older queen mostly cannot make the appropriate egg-laying pattern in the brood frame (Hasnat, 2018). The most favorable age is the 7-10th day of emergence for the instrumental insemination of queens. Insemination in these days of life also increases the survival of the queen. At this age, number of spermatozoa that enters into the spermatheca is also reasonable (Gerula et al., 2011). Other studies also stated the equal survival of both groups.

3.3 Oviposition and success rate

Instrumental insemination success depends upon the fecundity and survival of the queen and worker brood production. Most of the studies presented the data about the equal performance of NMQs and AIQs. Some assumptions are that the lack of mating flight may affect the performance of the queen, but also the opposite data are present, which show that this aspect does not affect the performance of the AIQs. However, there are some factors like the hive condition, seasonal effects etc., that affect oviposition in both the naturally mated queen and artificially inseminated queen. Recent studies suggested that physiology changed with the queen's age and according to the time of insemination. Optimal insemination occurs mostly at daylight, and the queens start oviposition at which were inseminated at the 2 pm to 3 pm as compared to the queens inseminated at the morning time. Time period difference between the insemination (insemination in AIQs and mating in NMQs) and the start of oviposition is different among artificially inseminated and naturally mated queens. As NMQs start oviposition within 2–4 days after mating. A study reported that NMQs produce more brood early oviposition than the AIQs, and these factors also depend upon the early emergence of the queen. And also the opposite study is present that the brood production is high in AIQs that start oviposition later than the NMQs in which the onset of oviposition is prior to other groups (Cobey, 2007). A study was reported by (Tibor et al., 1987) that oviposition starts in 1396 naturally mated queens in means average of 10 days in Alberta Canada.

Furthermore, Wilde (1994) examined queens for three years and presented data that onset of oviposition occurs in 77 AIQs after 10 to 37 days of emergence, and in NMQs onset of oviposition occurs after 7 to 26 days of emergence. The surroundings of the queen also affect the rate and time of oviposition. The presence of workers (nurse bees) also affects the rate of oviposition in both the NMQs and AIQs. A study of large data set of six years was reported from Poland about 1,289 AIQs in whom it was observed that oviposition time varied after emergence from 3 to 36 days. It was observed that oviposition started earlier in the queens which was inseminated about 5 to 12 days of emergence. About 2.9 % of AIQs started oviposition in 5 days, 67.7 % in 6 to 10 days and 90.4 % of queen’s onset of oviposition occurs in 15 days. It was also observed that oviposition is affected by brood type in the colony as the queen’s oviposition starts earlier in the colony, which has a young brood than the colony of the emerging brood. Humidity above 90 % and chilled nights also postponed the onset of oviposition (Skowronek et al., 2002). Chuda-Mickiewicz et al. (2003) reported a study of 79 AIQs and state that queens held in large mating nuclei start oviposition earlier as compared to the queens held with small population of worker bees in small nuclei. A study was reported by Woyke and (Ruttner, 1976) that AIQs illustrate a higher success rate (if inseminated properly) than the NMQs. According to (Woyke et al., 2008) onset of oviposition in artificial insemination do not occur due to the lack of contact with the drone's sting chamber. To prove this observation, queens were permitted to fly without drones on an island, and oviposition did not occur in these queens. Gerula et al. (2012) reported a study that the onset of oviposition occurs at 3 to 33 days to post insemination and did not affect by number of spermatozoa in the spermatheca. It was also reported that spermatozoa numbers are the same in both NMQs and AIQs. This report is similar to the observation of (Kaftanoglu and Peng, 1982), who start oviposition in virgin queens by treating CO2.

Other studies were presented by (Mackensen and Roberts, 1948; Wilde, 1994), which showed different results to this data. According to their studies, NMQs have high numbers of spermatozoa in the spermatheca than AIQs. There was a great difference in the number of spermatozoa in the spermatheca of NMQs and AIQs; NMQs have the high number of spermatozoa, according to these studies. In the process of instrumental insemination, conditions are established before the experiment, so the external factors mostly do not affect the results as compared to natural mating, in which external factors affect the mating success. Queens’s success of artificial insemination can be increased by the proper time of insemination. The best time for artificial insemination is when endeavoring to execute flights or returns without mating from the first flight. Avail this time for insemination can give the best results, as the number of spermatozoa could be the same as in the natural mating. Queen naturally mates at the age of seven days, or inseminated artificially could have the same number of spermatozoa in spermatheca (Gerula et al., 2012). Gerula et al. (2011) reported that oviposition start in 74 % NMQs which relate to the previous studies of (Woyke, 1960; Skowronek, 1976) who reported 69.5 % and 69 % of oviposition of queen respectively. According to (Gerula et al., 2011), oviposition start in 97 % AIQs, when inserting the 8 µL semen with a dose of CO2 of six minutes. Onset of oviposition according to (Ebadi and Gary, 1980) 80 to 90 %, (Moritz, 1984) 90 %, (Kühnert et al., 1989) 85 % (Konopacka, 1991) 50 % to 85 % occurs which depends upon the treatment of CO2. Further, Konopacka (1991) reported that 50 % onset of oviposition occurs in AIQs treated with CO2 for 30 s. Artificial insemination has been improved in recent years, and most of the success of the technique depends upon the inseminators’ skills.

3.4 Disease infestation

The endurance of any colony depends on the health of a queen. Queens is always less vulnerable to diseases than workers, but some viruses also damage the queen with the workers. The infestation rate of these viruses through instrumental insemination is very low (Prodělalová et al., 2019). Instrumental insemination also reduces the threat of transmission of dangerous pests (Buescu et al., 2015). In the natural mating, the queen mates with various drones, and the chances to getting disease also increase. But if the virus is present in the Ejaculates, both artificial insemination and natural mating are effective routes for transmitting the virus (Stoian et al., 2018).

There are two routes of transmission in honey bees; transmit either vertically (mother to progeny) or horizontally (between same generation individuals), also called venereal transmission). Venereal transmission is the direct route of transmission through food contamination, through contact of individuals, and most important is through drone sperms which ejaculated during natural mating and sometimes insertion of infected sperms during artificial insemination. There is another route of transmission, which is called the indirect or biological vectors route (Prodělalová et al., 2019). Prodělalová et al. (2019) reported that both artificial insemination and natural mating are efficient routes of transmission of the deformed wing virus (DWV). But the transmission of the DWV occurs mostly through natural mating because of mate with infectious drones. These viruses then transfer from queens to eggs, and whole colony could be destroyed and these viruses could be detected in fertilized eggs of the queen.

Using the ejaculate of an infected drone or queen mate with an infected drone both routes can develop a disease, so natural mating and artificial insemination could be the more effective routes of disease or infection transmission. The distribution of viruses and infections is the most important concern for the beekeepers and the authorities of the regions where artificial insemination is mostly practiced. Artificial insemination in which the queen is inseminated by the semen of one or several drones is also the most effective route of horizontal transmission of the virus, if the semen is not analyzed properly. But upto a limit, this transmission is controllable in artificial insemination as compared to natural mating, where drones from different regions with different viruses come.

4 Factors affecting the performance of artificially inseminated queens

Performance of the artificially inseminated queen is affected by the rearing conditions, stress, inseminator’s skills, nutrition, mating age of queen, queen banking, temperature, sperms stored in the spermatheca, sperms quality and quantity, semen handling and storage, CO2 and nitrogen treatments, pheromones (see Table 2). For the success of the insemination procedure optimization of these factors is necessary.

4.1 Rearing conditions

Success or the better performance of the AIQs depends upon the rearing queen and quality of drones. Weight at the time of rearing (emergence) affects the fecundity of queens. The less weighted queen’s egg-laying starts before, the more weighted queen. Acaricide’s presence in the rearing colony leads to lessen the fertility and age of queens and drones. Various studies have been reported on the effect of rearing conditions on the performance of AIQs (Haarmann et al., 2002; Skowronek et al., 2002).

The quality of the queen is directly dependent on the age of the larvae from which she emerged and the food given to this larva. If the queen is not inseminated at the proper time after emergence, this may lead to affect the queen's quality negatively. The conditions provided to the queen and drone at the time of rearing affect their quality and performance. To obtain the best results, it is needed to decrease the time period of drones’ storage because drones are stressed up very quickly. It is important to remove the stresses particularly chemical substances, parasites, pathogens, environmental conditions, and lack of nutrition (Buescu et al., 2015).

Notably, the best rearing environment is also a crucial factor to achieve the best results of AIQs. Various studies have been reported for the effect of rearing conditions on the performance of AIQs (Cobey, 2007). Drone’s storage space and the conditions given to them until maturity affect the results of instrumental insemination. Also the rearing conditions change the qualities of the queen if not handled properly (Buescu et al., 2015).

4.2 Stress factors

There are many factors which can cause stress and affect the results of the instrumental insemination process. These factors could be deficiency of food (to avoid this stress, give the pollen syrup to the rearing drones), pesticides deposits, miticides, poor climatic conditions, parasites, pathogens, and many other environmental issues. To obtain the best results, it is needed to decrease the time period of drones’ storage because drones are stressed up very quickly. It is important that to remove the stress factors for the success of the insemination process. Availability or lack of food to the drones during the larval stage affects their maturity by affecting the number and viability of sperms. Pollen absence also influences reproduction and development. Moreover, it is noted that environmental conditions and the genetics of drones affects the sperms count and viability (Haarmann et al., 2002; Buescu et al., 2015; Cobey, 2016).

4.3 Inseminator’s skills

The success of the insemination procedure also depends upon the inseminator’s skills, his/her attention, precision, and accuracy towards the procedure. The inseminator’s skills are, how to position the queen, open the vaginal cavity and bypass the valve fold and insert the semen. Queen and drone(s) care are the most important in insemination techniques (Cobey, 2016).

4.4 Food availability

Lack of food hinders the process of queen rearing and grafting, especially at brood production time, and resulting affects the instrumental insemination process. So it is recommendation that keep the queens with nurse bees with extra supplementation of food in the colony in pre and post-insemination (Hasnat, 2018). In AIQs the quality of the queen is totally based on the food that is provided to larvae by the nurse bees. Also, the nutrition supplies to the drone larva affect the viability of the sperms at maturity, and if the pollen is low at this developmental stage, it may decrease the reproductively of the drone (Buescu et al., 2015; Jagdale et al., 2021).

4.5 Mating age of queens

Queen can be instrumentally inseminated when she is of few days to few months, but the queen's age is the crucial factor that affects the queen’s performance (Cobey, 2007). Queen takes natural mating flights between the 4–13 days after emergence. In both, artificial or naturally queens have an optimal age for the receptiveness (this age is 4 – 13 after emergence in one study), which is different in different studies. If the mating is too early (before 5 days) or too late (after 14 days) low-quality queen will be produced, so try to avail this age of the queen (Buescu et al., 2015).

4.6 Seasonal effects

Environmental and seasonal conditions also affect the performance of queens. As the queens start mating earlier in the season, they lay eggs upto late in the season. So also for artificial insemination, this season is best. According to (Jhajj et al., 1992), the queen mates 5 days earlier and time to start egg-laying, lay eggs late in the season, about 11 days. Although genetic makeup plays a role in the fertility of a queen, the queen is more affected by the seasonal conditions than her genotype (Guler and Alpay, 2005).

4.7 Effects of banking queens

In the cages, the queen may not receive a proper diet. If the queen receives insufficient protein diet results in delayed egg-laying. After insemination, if the queens are limited to the cages increases the time period to oviposition, and pheromones development and also affects the sperm's storage. In the queen bank, the large number of queens can be placed and until the preparation of new colony or the instrumental insemination procedure. Several studies showed that, this practice of queen bank negatively affects the queen performance. So the conditions given to queens; caged or free in the nuclei, with nurse bees or without nurse bees before and after the insemination procedure also affect the performance of queen. The presence of nurse bees has a positive effect on the performance of artificially inseminated queens (Cobey, 2007).

4.8 Temperature

Temperature is an important factor that can affect the insemination method (Fig. 1). According to (Woyke & Jasinski, 1976), the temperature should be 34 °C before and after the insemination process. Gerula et al. (2011) recommended that the temperature of the location where to perform the experiment should be equal as the nest of the honeybees (Hasnat, 2018). Temperature variations, particularly at pupal development time affect the viability of sperms and the sexual maturity of the drones (Hasnat, 2018). Temperature is the most critical factor for sperm migration to the spermatheca (Buescu et al., 2015).

Quality queen production, natural vs artificial insemination, and factors affecting instrumental insemination.

If the temperature of the brood nest is low, it delays the egg-laying and also the success rate of the insemination procedure. The introduction pattern of the queens is to arrange in the clusters at low temperature, resulting in earlier oviposition (Cobey, 2007).

4.9 Number of sperm stored in the spermatheca of queens

Most of the studies suggested that queen is caging with the higher number of worker bees’ increases the success rate of the insemination procedure. Treatments given to the queen before and after the insemination procedure affect the storage of sperm cells in the spermatheca. Otten et al. (1998) observed that queens kept after insemination with 200 worker bees have the 70 % success rate and queen loss is 12 %, and the queens kept with 1200 worker bees have a 95 % success rate and 1 % queen loss. Gontarz et al. (2005) reported that the temperature of the cage with or without worker bees is always different, lower when the queen is virgin or nurse bees are recently introduced and high even after the 2 h. The sperm storage rate also increases with the increase in the number of worker bees in the cages.

Sperms stored by AIQs are less in numbers than the NMQs, while the numbers of sperms are larger in both groups (Cobey, 2007). In addition, sperms migration to the spermatheca from the lateral oviduct to the queen has affected by hive conditions, the size colony provided to the queen, and the temperature provided (Buescu et al., 2015). In Natural mating, only 10 % of the sperm are collected in the oviduct and stored in the spermatheca after mating with several drones. Queen caging after the process of insemination lessen the sperm movement to spermatheca (Cobey, 2007). According to the previous study by (Woyke and Jasinski, 1976), two sets of the queen was taken and give an Equal dose 8 µL of semen to them. One set was caged and the other was moving freely. Sperms stored in the spermatheca of the caged queen were 2.9 and 2.5 million, and sperms of freely moving queens were 4.2 million and 4.4 million. The storage of sperms in the spermatheca of queens mostly depends upon the nurse bees. Woyke and Jasiński (1990) artificially inseminated 70 queens in aged of 7–8 days with the semen dose of 8 µL, divided into three groups and provided different numbers of nurse bees to each group. 150 nurse bees were provided to group one, 350 to group second, and 750 to group third. Egg-laying started in 15 days in group first, 13.5 days in group second, and 11.5 days in group third. As the number of worker bees increased, queens lay eggs much earlier. When the number of worker bees up to 9500, the queen starts egg-laying in the average of 7 days because as the number of worker bees increases, the temperature of the clusters also increases. If the temperature increase up to 1 0C egg-laying could start 1 to 2 days earlier.

4.10 Quality and quantity of sperms

Semen entrance and maintenance in the oviduct lead to spermatheca in artificial insemination is affected by the insemination tip (Fig. 1). A study was reported by (Bieńkowska and Panasiuk, 2006), that 246 queens were inseminated artificially by inseminated tips with different diameters. About 72.3 % were inseminated by tip of 0.16 mm; clear the oviducts after insemination approximately in 48 h, but queens were inseminated by tip of diameter 0.19 mm, only 50.4 % of them cleared their oviduct.

Mating of the honey bee queens stimulates the changes in her behavior, functioning, gene expression, and pheromone release. The main benefit of instrumental insemination is queen can be inseminated by the semen of a single drone (called single drone insemination) or by the many drones (called multi-drone insemination). Pheromones released by the queens also depend upon the sperm quality sperm quantity, which results in changing worker activities (Richard et al., 2011). To obtain the best results by instrumental insemination volume of semen dose (standard volume of semen dose 8–12 µL), number of semen doses and best quality of sperms, its collection are the main factors (Hasnat, 2018).

4.11 Effects of semen handling and storage

Quality of sperms handling and dose also affect the performance of instrumentally inseminated queen (Fig. 1). Sperms' best handling is also an essential factor for best performance. Handling, physical and the chemical properties (nutrients, pH, osmolarity) of the sperm and diluents used for the insemination process can also affect the performance of AIQs (Collins, 2000).

Storage of sperms by the queen in the spermatheca is very important for the continuance of the best colony, and this storage is for her lifespan (3–5 years). The viability of the sperms remains constant in the spermatheca (globular organ with a diameter of 1.1 mm) of the queen for many years. Queen provides important ingredients (antioxidant, proteins, oxygen, sugars) to the sperms in spermatheca (Buescu et al., 2015). Honeybee semen can be stored at room temperature for two weeks, but storage should be dark because sunlight can also change the viability of the sperms. For short time storage, 21 °C is the optimal temperature, but the temperature may fluctuate between 13 and 25 °C (Hopkins and Herr, 2010; Cobey et al., 2013).

The cryopreservation technique could be used for long-term semen storage. In this technique cryoprotectants (dimethyl sulfoxide) could be used to avoid intracellular icing (Hopkins and Herr, 2010; Cobey et al., 2013). Other storage type is crioconserved (sperms storage in liquid nitrogen), but the queen inseminated by this type of stored semen mostly layed unfertilized eggs (Buescu et al., 2015). Slow cooling upto −3 °C may maintain the 93 % viability of sperms and if cooling speedily goes to zero, viability remains 13 %, so the slow cooling to avoid heatstroke is very important (Hopkins and Herr, 2010).

4.12 Effects of carbon dioxide and nitrogen treatments

Queens are anesthetized with CO2 during the insemination process. This treatment also has the positive effect on the oviposition (Susan W Cobey, 2007). Anesthetize the queen with CO2 gas to start oviposition in virgin queens. It was reported that two treatments of CO2 gas (each treatment of 3 min) diminish the harmful effects of anesthesia, and at the same time 70 % of queens started egg-laying (within 15 days) after the insemination (Gerula et al., 2011). A high concentration of CO2 is also harmful to the other members (workers) of the colony. Workers start their work outside the hive/colony earlier because the worker's ages are faster and live a very short life. The worker bees who lived under the influence of CO2 develop less body fats, and the development of the wax glands and hypopharyngeal glands is repressed (Chuda-Mickiewicz et al., 2012). If the concentration of CO2 is over 80 % and remains for more than 3 min has harmful effects. This harmful effect of CO2 gas can be moderated by the use of nitrogen (N2) gas in anesthesia (Czekońska, 2009).

Nitrogen treatments with CO2 also increase the attractiveness of the worker bees towards the queen. It is suggested that nitrogen has the neutral effect on the bees (Chuda-Mickiewicz et al., 2012). But the low volume of nitrogen is more effective for anesthesia of worker bees than a higher volume of nitrogen (Czekońska, 2009). Two treatments of CO2 are suggested to increase the fecundity and decrease the latency period of the queens. The first treatment is one or two days before the insemination, and the second treatment is just before the insemination procedure and these treatments also have the positive effect on the sperm migration into the oviduct after insemination. Some studies reported that CO2 treatment causes the weight loss of the queen in the first phase if received two CO2 treatments (Buescu et al., 2015; Hasnat, 2018).

4.13 Pheromones

Queen undergoes many physiological and behavioral changes during her virgin and mated life span. Pheromones released by virgin queens also have a different composition than the mated queens. Pheromones in the queens have been produced by Dufour’s and mandibular glands. Queen pheromones consists of 9-oxo-(E) 2-decenoic acid (ODA), (R)- and (S)-9-hydroxy-(E)-2-decenoic acid (9-HDA), methyl p-hydroxybenzoate (HOB), and 4-hydroxy-3 methyoxyphenylethanol (HVA). Worker behavior and physiology are affected for the short term or long term by QMPs (Richard et al., 2007). Morevoer, queen pheromone is a mix of chemical substances like 9-oxo-(E)-2-decenoic acid, (R)- and (S)-9–hydroxy-(E)-2-decenoic acid, methyl p -hydroxybenzoate, 4–hydroxy–3-methyoxyphenylethanol, palmityl alcohol, methyl oleate, linolenic acid and coniferyl alcohol (Trhlin and Rajchard, 2011). Pheromones have many functions like aggregation, mate attraction, and other biological behavior of the queen and workers. The production of hormones is affected by CO2, semen quality and quantity, and inseminator’s skills for the manipulation of the genital tract during insemination (Cobey, 2016).

5 Conclusions

This review is about the quality queen production, a comparative study of artificially inseminated and naturally mated queens, and some factors which affect the performance of artificially inseminated queen. Most of the studies are presented about quality queen production. The larva is reared artificially in the laboratory under controlled conditions. After rearing, when the larva develops into a queen (virgin queen), kept in the hive and allowed for natural mating or artificially inseminated in the laboratory. This review presents the data about the comparison of artificially inseminated queens and naturally mated queens, in which most of the studies support artificial insemination. A large data set is presented from 1940 s to the present time which concludes that the productivity of the colonies headed by the artificially inseminated queens is higher. The consistency of the artificial insemination method illustrates that this method can be used for the control and selective breeding of bees Apis mellifera. L, and is also an efficient tool for stock management. Treatments and the surrounding conditions affect the performance of both artificially inseminated queens and naturally mated queens. If the beekeeping is not properly done, it may affect the performance of the queens in both groups. Sperm cell migration (from the lateral oviduct to spermatheca of the queen) is affected by the queen age, queen caging, and nest or hive temperature. Queen survival is directly dependent on the storage of sperms in the spermatheca. Quantity and quality of semen dosage and semen handling affect the results of artificial insemination. These all factors are controllable and to get the best results of artificial insemination, all factors should be optimized with appropriate beekeeping practices.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate the support of the Research Center for Advanced Materials Science (RCAMS) at King Khalid University Abha, Saudi Arabia through a project number RCAMS/KKU/001-21. This research work was also supported by Agricultural Linkages Program – project entitled “Superior Quality honeybee queen production through Non- traditional Techniques” under Grant No. ALP NR- 047 of Honeybee Research Institute (HBRI), National Agricultural Research Centre (NARC), Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC), federal Ministry of National Food Security and Research Islamabad, Pakistan.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Genetic network analysis between Apis mellifera subspecies based on mtDNA argues the purity of specimens from North Africa, the Levant and Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(5):2718-2725.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improvement of artificial feeding in a standard in vitro method for rearing Apis mellifera larvae. Bull. Insectol. 2005;58(2):107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of the diameter of the inseminating needle tip on the results of bee queens’ fertilization. J. Apic. Sci. 2006;50(2):137-145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Artificial Insemination on Apis mellifera–aspects of Artificial Inseminated Queen Performances And Factors That May Affect Their Performance. The publishing house of the Romanian Academy; 2015.

- Evaluation of artificially inseminated and naturally mated bee queens in Zubri. Czech Republic (in Czech) Vcelarstvi. 2004;57:148-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Success rates for instrumental insemination of carbon dioxide and nitrogen anaesthetised honey bee (Apis mellifera) queens. J. Apic. Res.. 2012;51(1):74-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Onset of oviposition in honey bee queens kept in boxes with non-free flying bees. J. Apic. Sci.. 2003;47(1):27-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of colony performance of instrumentally inseminated and naturally mated honey bee queens. In: Proceedings of American Bee Research Conference, Colorado Springs, CO, USA. American Bee Journal; 1998. p. :292.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison studies of instrumentally inseminated and naturally mated honey bee queens and factors affecting their performance. Apidologie. 2007;38(4):390-410.

- [Google Scholar]

- An introduction to instrumental insemination of honey bee queens. Bee World. 2016;93(2):33-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Standard methods for instrumental insemination of Apis mellifera queens. J. Apic. Res.. 2013;52(4):1-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between semen quality and performance of instrumentally inseminated honey bee queens. Apidologie. 2000;31(3):421-429.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of different substrates on the acceptance of grafted larvae in commercial honey bee (Apis Mellifera) queen rearing. J. Apic. Sci.. 2017;61(2):245-251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Standard methods for artificial rearing of Apis mellifera larvae. J. Apic. Res.. 2013;52(1):1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of different concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) in a mixture with air or nitrogen upon the survival of the honey bee (Apis mellifera) J. Apic. Res.. 2009;48(1):67-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting survival, migration of spermatozoa and onset of oviposition in instrumentally inseminated queen honeybees. J. Apic. Res.. 1980;19(2):96-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors, based on common practices, affecting the results of instrumental insemination of honey bee queens. Apidologie. 2018;49(6):773-780.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are sperm traits of drones (Apis mellifera L.) from laying worker colonies noteworthy? J. Apic. Res.. 2011;50(2):130-137.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why the viability of spermatozoa diminishes in the honeybee (Apis mellifera) within short time during natural mating and preparation for instrumental insemination. Apidologie. 2014;45(6):757-770.

- [Google Scholar]

- Instrumental insemination of honey bee queens during flight activity predisposition period 1. Onset of oviposition. J. Apic. Sci.. 2011;55(2):53-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Instrumental insemination of honey bee queens during flight activity predisposition period 2. Number of spermatozoa in spermatheca. J. Apic. Sci.. 2012;56(1):159-167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of queen caging conditions on insemination results. J. Apic. Sci. 2005;49(1):5-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reproductive characteristics of some honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) genotypes. J. Anim. Vet. Adv.. 2005;4(10):864-870.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of fluvalinate and coumaphos on queen honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in two commercial queen rearing operations. J. Econ. Entomol.. 2002;95(1):28-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Viability of honey bee eggs from progeny of frozen spermatozoa. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am.. 1981;74(5):482-486.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oviposition rates of instrumentally inseminated and naturally mated queen honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am.. 1986;79(1):112-115.

- [Google Scholar]

- Harbo, J.R. (1986b). Propagation and instrumental insemination.

- Hasnat, M. (2018). “Reproductive Potential Difference of Artificially Inseminated and Naturally Mated Honey Bee Queens (Apis mellifera L.)”.).

- A review of methods used in some European countries for assessing the quality of honey bee queens through their physical characters and the performance of their colonies. J. Apic. Res.. 2014;53(3):337-363.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting the successful cryopreservation of honey bee (Apis mellifera) spermatozoa. Apidologie. 2010;41(5):548-556.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparisons of the queen volatile compounds of instrumentally inseminated versus naturally mated honey bee (Apis mellifera) queens. Apidologie. 2009;40(4):464-471.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional profile and potential health benefits of super foods: a review. Sustainability. 2021;13(16):9240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of queen trap for Apis mellifera L. and studies on the premating period. Indian Bee J.. 1992;5:63-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of insemination on the initiation of oviposition in the queen honeybee. J. Apic. Res.. 1982;21(1):3-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- An investigation of the efficacy of hygienic behavior of various honey bee (Apis mellifera) races toward Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) mite infestation. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci.. 2021;33(3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Queen cells acceptance rate and royal jelly production in worker honey bees of two Apis mellifera races. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4)

- [Google Scholar]

- Honey bee (Apis mellifera) preference towards micronutrients and their impact on bee colonies. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(6):3362-3366.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of mating and instrumental insemination on queen honey bee flight behaviour and gene expression. Insect Mol. Biol.. 2010;19(2):153-162.

- [Google Scholar]

- Konopacka, Z. (1991). Effect of CO2 and N2O anaesthetics on results of instrumental insemination of honey bee queens. Pszczelnicze Zeszyty Naukowe (Poland).

- Use of homogenized drone semen in a bee breeding program in Western Australia. Apidologie. 1989;20(5):371-381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relation of semen volume to success in artificial insemination of queen honey bees. J. Econ. Entomol.. 1964;57(4):581-583.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of carbon dioxide on initial oviposition of artificially inseminated and virgin queen bees. J. Econ. Entomol.. 2014;40(3):344-349.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mackensen, O., and Roberts, W. (1948). A manual for the artificial insemination of queen bees.

- Effects of the age of grafted larvae and the effects of supplemental feeding on some morphological characteristics of Iranian queen honey bees (Apis mellifera meda Skorikov, 1929) J. Apic. Sci.. 2012;56(1):93-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of different diluents on insemination success in the honeybee using mixed semen. J. Apic. Res.. 1984;23(3):164-167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D., and Laidlaw, H. (1988). An evaluation of instrumentally inseminated queens shipped in packages.

- Artificial insemination: Methodological influence on the results. Apidologie (France) 1998

- [Google Scholar]

- A scientific note on using large mixed sperm samples in instrumental insemination of honeybee queens. Apidologie. 2017;48(5):716-718.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of performance of bee colonies with naturally mated and artificially inseminated queens (Am carnica) Apidologie. 2002;33:513.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple virus infections in western honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) ejaculate used for instrumental insemination. Viruses. 2019;11(4):306.

- [Google Scholar]

- Queen honey bee introduction and early survival–effects of queen age at introduction. Apidologie. 2004;35(4):383-388.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of instrumental insemination and insemination quantity on Dufour’s gland chemical profiles and vitellogenin expression in honey bee queens (Apis mellifera) J. Chem. Ecol.. 2011;37(9):1027-1036.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of insemination quantity on honey bee queen physiology. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(10):e980.

- [Google Scholar]

- Varroa in the mating yard. I. The effects of varroa jacobsoni and apistan on drone honey bees. AmerIcan Bee J. (USA) 1999

- [Google Scholar]

- Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) drone sperm quality in relation to age, genetic line, and time of breeding. Can. Entomol.. 2015;147(6):702-711.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ruttner, F. (1976). “The instrumental insemination of the queen bee”.).

- Seasonal variations of colony activities linked to morphometric and glands characterizations of hybrid Carniolan honey bee (Apis mellifera carnica Pollmann) workers. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci.. 2021;33(6)

- [Google Scholar]

- Mating behavior of queen honey bees after carbon dioxide anaesthesia. Pszcelnicze Zeszyty Nnaukowe. 1976;20:99-115.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting oviposition of artificially inseminated honeybee queens. J. Apic. Sci.. 2002;2(46)

- [Google Scholar]

- Technical, sanitary and environmental sequences to improve artificial insemination of honey bee, Apis mellifera. Part I. Experimental results. Anim. Biol. Anim. Husb.. 2018;10(2):122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of honeybee queen weight and air temperature on the initiation of oviposition. J. Apic. Res.. 1987;26(2):73-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical communication in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.): a review. Vet. Med.. 2011;56(6):265-273.

- [Google Scholar]

- mixing and storing large volumes of honeybee (Apis. meliferra meliferra) sperm integrated in breeding program. Proc. Neth. Entomol. Soc. Meet. 2014;25:39-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Der Einfluss der künstlichen Besamung auf die Leistungszucht. Bienenvater. 1984;105:332-335.

- [Google Scholar]

- The development and productivity of honey bee colonies with naturally mated and artificially inseminated queens. Proc. XXX1st International Apimondia Congress, Warsaw, Poland 1987:442-444.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of keeping queen honey bees after instrumental insemination on their performance. Acta Academiae Agricultural Technicae Olstenensis, Zootechnica. 1994;39:153-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Naturalne i sztuczne unasienianie matek pszczelich. Pszczelnicze Zeszyty Naukowe. 1960;4(3/4):183-275.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural and artificial insemination of queen honeybees. Bee World. 1962;43(1):21-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors that determine the number of spermatozoa in the spermatheca of naturally mated queens. Z. Bienenforsch.. 1966;8:236-247.

- [Google Scholar]

- Woyke, J. (1988). Problems with queen banks.

- Correct queen maintenance before and after instrumental insemination, tested in Egypt. J. Apic. Res.. 1989;28(4):187-190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of natural mating of instrumentally inseminated queen honeybees by proper method of instrumental insemination. J. Apic. Sci.. 2001;45(1):101-114.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of age on the results of instrumental insemination of honeybee queens. Apidologie. 1976;7(4):301-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the dynamics of entry of spermatozoa into the spermatheca of instrumentally inseminated queen honey bees kept under different conditions. Pszczelnicze Zeszyty Naukowe. 1985;29:377-388.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of the number of attendant worker bees on the initiation of egg laying by instrumentally inseminated queens kept in small nuclei. J. Apic. Res.. 1990;29(2):101-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Further investigations on natural mating of instrumentally inseminated Apis mellifera queens. J. Apic. Res.. 1995;34(2):105-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Onset of oviposition by honey bee queens, mated either naturally or by various instrumental insemination methods, fits a lognormal distribution. J. Apic. Res.. 2008;47(1):1-9.

- [Google Scholar]