Translate this page into:

Insights into the phylogenetic relationship of the lamiids orders based on whole chloroplast genome sequencing

⁎Corresponding author. m.alawfe-7@hotmail.com (Mohammad S. Alawfi),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Lamiids, an asterid clade consists of over 40,000 species distributed among eight orders, Icacinales, Garryales and Metteniusales, known informally as “basal lamiids”, Boraginales, Gentianales, Lamiales, Solanales, and Vahliales, known informally as “core lamiids”. Over recent years, different phylogenetic studies have clarified the formation of lamiids, however, the relationships among the orders remain unresolved. The whole chloroplast genome sequences of 49 taxa have been downloaded from GenBank (NCBI) and used to evaluate the evolutionary relationships of lamiids, and particularly to test the relationships among the main lineages of lamiids. The phylogenetic tree resulting from using Maximum Parsimony and Bayesian Inference were with identical topologies and provide good support for the following relationships, Lamiales as sister to Solanales, and Boraginales as sister to Gentianales together forming the core lamiids. In basal lamiids, the result support Garryales as sister to Metteniusales, while Icacinales was found to be the immediate sister to the other orders in the core lamiids. Our results may improve our understanding of the relationships between the orders of lamiids.

Keywords

Basal lamiids

Chloroplast genome

Core lamiids

Phylogenetic relationship

Systematics

1 Introduction

Asterids is the largest group in eudicots and comprising two clades, campanulids and lamiids (Zhang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). The lamiids are the largest, most species-rich and most diverse clade of asterids, with estimates ranging between 40,000 to 50,000 species, representing 15% of eudicots (Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead, 2014; Yang et al., 2020). According to the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG IV, 2016), the clade is composed of eight orders, Icacinales (Include Icacinaceae and Oncothecaceae), Garryales and Metteniusales, referred to informally as “basal lamiids”. The rest of the lamiids include Boraginales, Gentianales, Lamiales, Solanales, and Vahliales, known informally as “core lamiids”. Different phylogenetic studies strongly favoured the monophyly of the clade (Albach et al., 2001; Soltis et al., 2011; Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead, 2014). The lamiids has been referred to by several names including asterids I, euasterids I or lamiidae (Takhtajan, 1987; Chase et al., 1993, APG I, 1998. Olmstead et al., 2000; Soltis et al., 2000, APG II, 2003; Soltis et al., 2011). Multiple characters of lamiids have been inferred as ancestral states such as woody habit, superior ovaries, unitegmic ovules, trilacunar nodes, scalariform perforation plates, presence of iridoids cellular endosperm and opposite leaves (Stull et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022). However, considerable morphological differences within the lamiids clade, the non-molecular synapomorphies are uncertain (Stull et al., 2015).

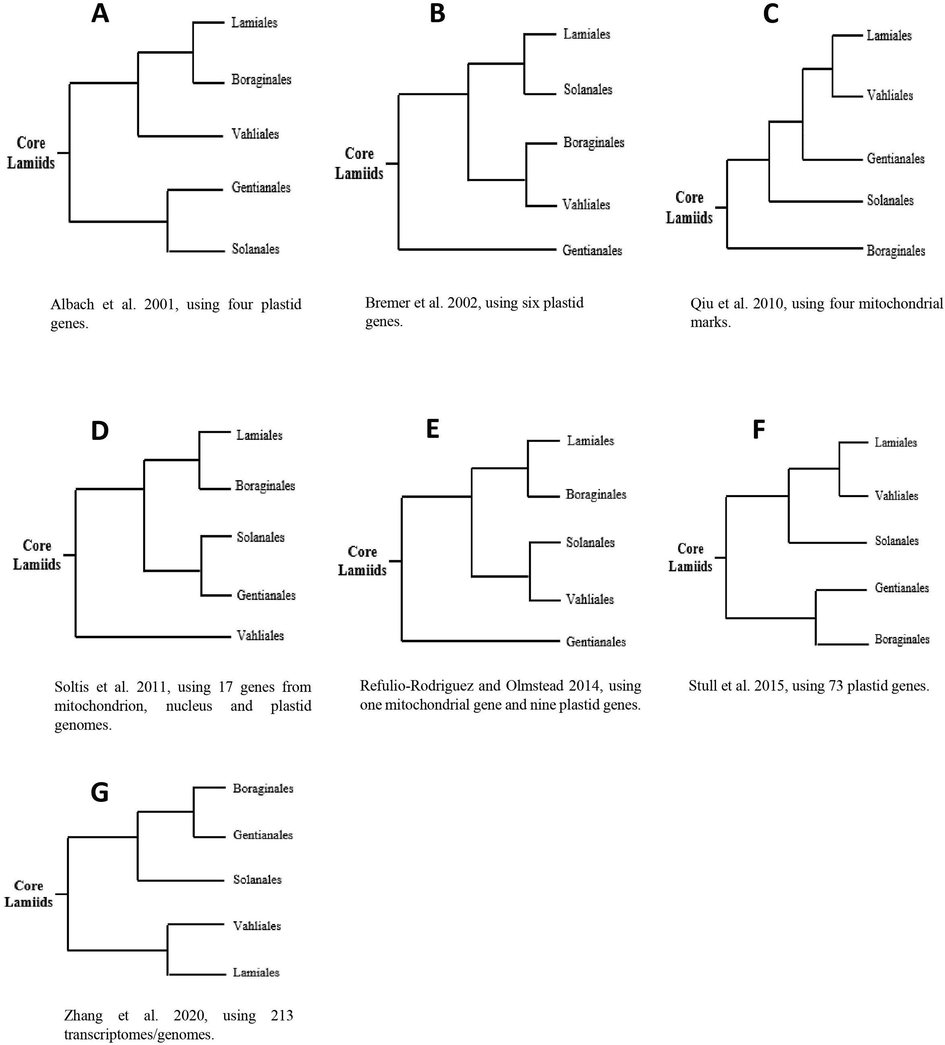

The formation of lamiids has been clarified by numerous phylogenetic studies during the last few decades. However, the relationships among the orders of lamiids remain unclear or inconsistent. Firstly, the evolutionary relationships amongst the core lamiids group, Boraginales, Gentianales, Lamiales, Solanales, and Vahliales are contradictory (Fig. 1 A-G). Based on one nucleus gene (18S) and three chloroplast genes (atpB, ndhF and rbcL) Albach et al. (2001) (Fig. 1-A) have found support for the relationships (((Lamiales–Boraginales), Vahliales), Gentianales–Solanales) with strong Maximum Parsimony (MP) support. Bremer et al. (2002) (Fig. 1-B) recovered a different topology (((Lamiales–Solanales), Boraginales–Vahliales), Gentianales) using six plastid genes (rbcL, ndhF, matK, trnL, trnV and rps16), however, the MP support was low. Qiu et al. (2010) (Fig. 1-C) based on four mitochondrial marks (atp1, matR, nad5, and rps3) obtained different relationships ((((Lamiales–Vahliales), Gentianales), Solanales), Boraginales) but with low Maximum Likelihood (ML) support. Soltis et al. (2011) (Fig. 1-D) recovered the pattern (((Boraginales–Lamiales), Solanales–Gentianales), Vahliales) using 17 genes including two nucleus genes (18S and 26S rDNA), eight plastid genes (rbcL, rpoC2, rps16, rps4, psbBTNH, ndhF, matK, and atpB), and four mitochondrial marks (rps3, nad5, matR, and atp1) with strong ML support. Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead (2014) (Fig. 1-E) using one mitochondrial gene (rps3) and nine chloroplast genes (trnV-atpE, trnL-F, rps16, rps4, rbcL, psbBTNH, ndhF, matK and atpB) have recovered (((Boraginales–Lamiales), Solanales–Vahliales), Gentianales) with moderate ML support but strong Bayesian Inference (BI) support. Stull et al. (2015) (Fig. 1-F) have recognized a different topology (((Lamiales – Vahliales), Solanales), Gentianales–Boraginales) based on 73 protein-coding genes, with strong BI support, however, ML support was low. Zhang et al. (2020) (Fig. 1-G) recovered (((Boraginales–Gentianales), Solanales), Vahliales–Lamiales) based on 213 transcriptomes/genomes, with strong ML support.

Seven different topologies from previous phylogenetic studies show different results in identifying the evolutionary relationship among the core lamiids.

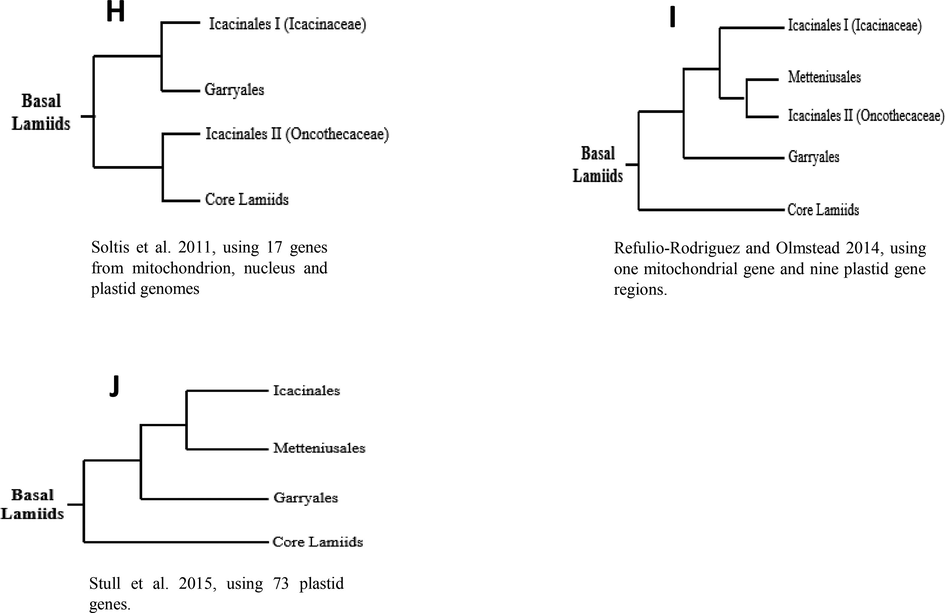

Secondly, the relationships between the other three lamiids orders, Icacinales, Garryales, and Metteniusales are controversial. Soltis et al. (2011) (Fig. 2-H) recovered the pattern ((Icacinaceae– Garryales), Oncothecaceae) with moderate ML support, however, Metteniusales order was not included. Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead (2014) (Fig. 2-I) recovered a different relationship (((Icacinaceae), Metteniusales–Oncothecaceae), Garryales) with weak BI, ML and MP support. Stull et al. (2015) (Fig. 2-J) have found support for the relationships ((Icacinales–Metteniusales), Garryales) with relatively strong ML support. Moreover, Metteniusales was found to be the immediate sister to the core lamiids in Gonzalez et al. (2007), Icacinales by Soltis et al. (2011), and it was Garryales in Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead (2014) and Stull et al. (2015).

Three different topologies from previous phylogenetic studies show different results in identifying the evolutionary relationship among the basal lamiids.

Generally, as reviewed above, the relationships among the major lineages of lamiids have suffered from instability. Most of the phylogenetic studies that covered the evolutionary relationships between the orders of the lamiids were based on a few markers or genes (including chloroplast, nucleus and mitochondrial DNA). Using a single or a few genes may lead to different results in identifying the evolutionary relationship among species in comparison to chloroplast (cp) genome sequencing, which is based on the whole genome (Yao et al., 2020). Since the plastid genome approach has the capacity to resolve evolutionary relationships among some complex taxa (Huang et al., 2020). The plastid genome has been extensively used in plant phylogenetic studies (Adachi et al., 2000). The chloroplast genome of angiosperms species highly conserved in term of structural, gene content and arrangement (Fonseca et al., 2022). In this work, we sought to cover the relationships among the major lineages of lamiids reported in previous studies and determine the closest relatives of each order using chloroplast genome sequences data. Systematics is discussed in light of the phylogenetic analyses.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Samples sequences

The chloroplast genome sequences of 49 taxa, 47 that represent all major lineages identified to date within lamiids (except Vahliales; the cp genome of this order was not available) and two taxa represent campanulids clade as outgroup were downloaded from Genbank - NCBI (Table 1). MAFFT v.7 was used to align all of the downloaded cp genome sequences (Katoh and Standley, 2013).

Order

Family

Species

Accession Number

1

Garryales

Garryaceae

Aucuba obcordata

NC_056113

2

Icacinales

Icacinaceae

Iodes cirrhosa

NC_036304

3

Metteniusales

Metteniusaceae

Pittosporopsis kerrii

MK488090

4

Boraginales

Boraginaceae

Arnebia euchroma

NC_053782

5

Boraginales

Boraginaceae

Borago officinalis

NC_046796

6

Boraginales

Boraginaceae

Lithospermum erythrorhizon

NC_053783

7

Boraginales

Boraginaceae

Onosma fuyunensis

NC_049569

8

Boraginales

Ehretiaceae

Ehretia dicksonii

MZ555766

9

Gentianales

Apocynaceae

Alstonia scholaris

NC_057091

10

Gentianales

Apocynaceae

Apocynum venetum

NC_053902

11

Gentianales

Apocynaceae

Periploca forrestii

NC_056319

12

Gentianales

Apocynaceae

Vincetoxicum hainanense

NC_051946

13

Gentianales

Gelsemiaceae

Gelsemium elegans

MH327990

14

Gentianales

Gentianaceae

Eustoma exaltatum

MK991810

15

Gentianales

Gentianaceae

Exacum affine

NC_056993

16

Gentianales

Gentianaceae

Fagraea fragrans

NC_057263

17

Gentianales

Gentianaceae

Gentiana manshurica

NC_053840

18

Gentianales

Loganiaceae

Mitrasacme pygmaea

NC_050922

19

Gentianales

Loganiaceae

Mitreola yangchunensis

NC_050923

20

Gentianales

Rubiaceae

Cinchona officinalis

MZ151891

21

Gentianales

Rubiaceae

Dunnia sinensis

MN883829

22

Gentianales

Rubiaceae

Emmenopterys henryi

NC_036300

23

Lamiales

Acanthaceae

Acanthus ilicifolius

MW752129

24

Lamiales

Bignoniaceae

Tanaecium tetragonolobum

KR534325

25

Lamiales

Carlemanniaceae

Silvianthus bracteatus

NC_047484

26

Lamiales

Gesneriaceae

Boea hygrometrica

NC_016468

27

Lamiales

Lamiaceae

Lamium takeshimense

MN240520

28

Lamiales

Lentibulariaceae

Genlisea violacea

NC_037083

29

Lamiales

Linderniaceae

Torenia benthamiana

NC_045273

30

Lamiales

Mazaceae

Mazus xiuningensis

NC_056340

31

Lamiales

Oleaceae

Olea europaea

MT182986

32

Lamiales

Paulowniaceae

Paulownia elongata

MK805127

33

Lamiales

Plantaginaceae

Plantago depressa

NC_041161

34

Lamiales

Scrophulariaceae

Verbascum phoeniceum

MN893301

35

Lamiales

Verbenaceae

Verbena officinalis

MW348926

36

Solanales

Convolvulaceae

Convolvulus arvensis

NC_054224

37

Solanales

Convolvulaceae

Cressa cretica

NC_035516

38

Solanales

Convolvulaceae

Evolvulus alsinoides

MN548282

39

Solanales

Convolvulaceae

Ipomoea ramosissima

NC_041205

40

Solanales

Solanaceae

Capsicum lycianthoides

NC_026551

41

Solanales

Solanaceae

Datura stramonium

MT610897

42

Solanales

Solanaceae

Hyoscyamus niger

KF248009

43

Solanales

Solanaceae

Lycium ferocissimum

MN866909

44

Solanales

Solanaceae

Nicandra physalodes

MN165114

45

Solanales

Solanaceae

Nicotiana attenuata

MG182422

46

Solanales

Solanaceae

Physalis minima

NC_048515

47

Solanales

Solanaceae

Solanum anguivi

NC_039611

48

Aquifoliales

Helwingiaceae

Helwingia chinensis

MZ504968

49

Apiales

Araliaceae

Kalopanax septemlobus

NC_022814

2.2 Phylogenetic analysis - Maximum Parsimony (MP)

Maximum parsimony PAUP version 4.0b10 was used to analyze the aligned sequences (Felsenstein, 1978). The heuristic searches were assessed with 100,000 replicates of branch swapping, tree bisection reconnections and random taxon addition. Non-parametric bootstrap analysis was determined with 1,000 replicates to evaluate branch support.

2.3 Phylogenetic analysis - Bayesian inference (BI)

MrBayes version 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al., 2012) was used to perform Bayesian inference, and the best substitution model (GTR + G) was identified using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) in jModelTest version 3.7. (Posada, 2008). MrBayes was run for 1,000,000 generations with two separate Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses, sampling and printing every 500 generations. Both constructed trees from (MP) and (BI) were edited and visualized using FigTree version 1.4.4.

3 Results

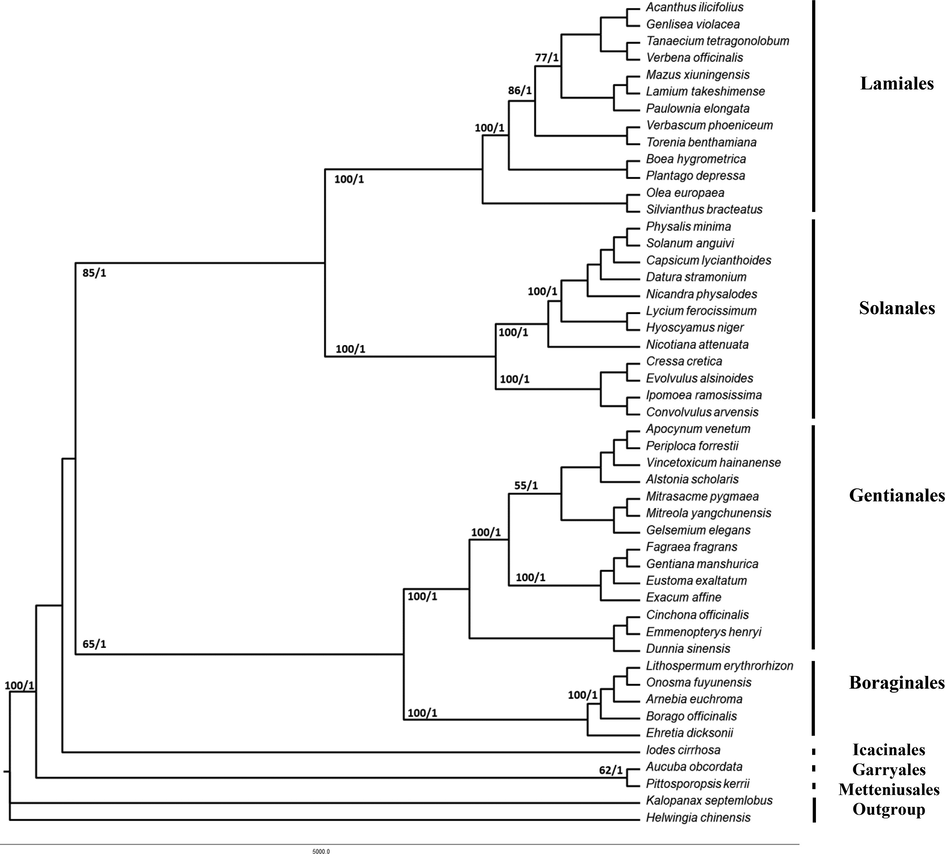

The topologies resulting from the Maximum Parsimony and Bayesian analyses were virtually identical. The phylogenetic tree is presented in Fig. 3 with bootstrap (BS) and posterior probability (PP) support values. The basal lamiids together with core lamiids formed a strongly supported clade (BS = 100, PP = 1).

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction of the 49 species based on the whole plastid genomes using Maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses; the tree illustrate the relationships among the major lineages of lamiids and the figures in the branch nodes represent the total of bootstrap (BS)/posterior probability (PP).

3.1 Phylogenetic Inference: Relationships within basal lamiids

The first clade to diverge in basal lamiids consists of Garryales and Metteniusales were recovered as a sister but with strong support only from PP (BS = 62, PP = 1), while Icacinales was found to be the immediate sister to the core lamiids.

3.2 Phylogenetic Inference: Relationships within core lamiids

The core lamiids formed a strongly supported clade (BS = 100, PP = 1). Lamiales and Solanales were recovered as sister with strong support (BS = 85, PP = 1), while Boraginales and Gentianales were recovered as a sister but with strong support only from PP (BS = 65, PP = 1).

4 Discussion

4.1 Phylogeny of basal lamiids

The first clade to diverge consists of Garryales and Metteniusales (Fig. 3). This finding contrasts with Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead (2014) and Stull et al. (2015), which they have suggested that Metteniusales is sister to Icacinales. The results also indicate that Icacinales are the immediate sister to the other orders within the core lamiids. This is accordant with Soltis et al. (2011).

4.2 Phylogeny of core lamiids

Lamiales and Solanales are recovered as sisters, consistent with Bremer et al. (2002) and Stull et al. (2015). The second clade consists of Boraginales and Gentianales. This finding is consistent with Stull et al. (2015) and Zhang et al. (2020). However, several previous phylogenetic studies identified different relationships between the orders within core lamiids in comparison to our findings. For example, Lamiales was recovered as sister to Boraginales in Albach et al. (2001), Soltis et al. (2011) and Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead (2014), as sister to Vahliales and Gentianales in Qiu et al. (2010). Also, Solanales was recovered as sister to Gentianales in Albach et al. (2001) and Soltis et al. (2011), as sister to Vahliales in Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead (2014), as sister to Boraginales and Gentianales in Zhang et al. (2020). In addition, Boraginales was recovered as sister to Lamiales in Albach et al. (2001), Soltis et al. (2011) and Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead (2014), as sister to Vahliales in Bremer et al. (2002), the earliest branch to diverge and sister to all other orders in Qiu et al. (2010). Moreover, Gentianales was recovered as sister to Solanales in Albach et al. (2001) and Soltis et al. (2011), the earliest branch to diverge and sister to the all other orders in Bremer et al. (2002) and Refulio-Rodriguez and Olmstead (2014), as sister to Lamiales and Vahliales in Qiu et al. (2010).

5 Conclusion

Larger-scale phylogenetic studies of angiosperms have not definitively determined the relationships among the major lineages of lamiids. Most of the molecular analyses that covered the evolutionary relationships within the lamiids were based on a few markers or genes. Using whole chloroplast genome sequencing gives a more reliable result in identifying the evolutionary relationship among species in comparison to the use of a few genes. In this study, we used 49 whole chloroplast genome sequences, 47 taxa that represent all major lineages identified to date within lamiids except Vahliales; the cp genome of this order was not available, while two taxa represent campanulids clade as outgroup. In basal lamiids clade, our results suggest that Garryales as sister to Metteniusales, while Icacinales is the immediate sister to the other orders within the core lamiids. In core lamiids, Lamiales was found to be sister to Solanales, and Boraginales as sister to Gentianales. This finding increases our understanding of relationships among lineages of lamiids. However, these relationships need more fully investigated with additional sequence data and taxa, especially the chloroplast genome sequence of Vahliales taxa, which was not sampled in the present study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Plastid genome phylogeny and a model of amino acid substitution for proteins encoded by chloroplast DNA. J. Mol. Evol.. 2000;50(4):348-358.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic analysis of asterids based on sequences of four genes. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard.. 2001;88(2):163-212.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard.. 1998;85(4):531-553.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetics of asterids based on 3 coding and 3 non-coding chloroplast DNA markers and the utility of non-coding DNA at higher taxonomic levels. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.. 2002;24(2):274-301.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetics of seed plants: An analysis of nucleotide sequences from the plastid gene rbcL. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard.. 1993;80(3):528.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cases in which parsimony or compatibility methods will be positively misleading. Syst. Zool.. 1978;27(4):401-410.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Putting small and big pieces together: a genome assembly approach reveals the largest Lamiid plastome in a woody vine. Peer J.. 2022;10:e13207.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metteniusaceae, an early-diverging family in the lamiid clade. Taxon. 2007;56(3):795-800.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative chloroplast genomics of fritillaria (Liliaceae), inferences for phylogenetic relationships between fritillaria and lilium and plastome evolution. Plants.. 2020;9(2)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Bot. J. Linnean Soc.. 2003;141(4):399-436.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linnean Soc.. 2016;181(1):1-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2013;30(4):772-780.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plastid phylogenomic insights into relationships of all flowering plant families. BMC Biol.. 2021;19(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The phylogeny of the Asteridae sensu lato based on chloroplast ndhF gene sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.. 2000;16(1):96-112.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- jModelTest: Phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2008;25(7):1253-1256.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Angiosperm phylogeny inferred from sequences of four mitochondrial genes. J. System. Evol.. 2010;48(6):391-425.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mrbayes 3.2: Efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol.. 2012;61(3):539-542.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Angiosperm phylogeny inferred from 18S rDNA, rbcL, and atpB sequences. Bot. J. Linnean Soc.. 2000;133(4):381-461.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Resolving basal lamiid phylogeny and the circumscription of icacinaceae with a plastome-scale data set. Am. J. Botany.. 2015;102(11):1794-1813.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Character evolution and missing (morphological) data across asteridae. American J. of Botany.. 2018;105(3):470-479.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Takhtajan, A. L., 1987. Sistema Magnoliofitov = Systema Magnoliophytorum. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Quantifying the Variation in the Geometries of the Outer Rims of Corolla Tubes of Vinca major L. Plants.. 2022;11(15):1987.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of angiosperm pollen: 8. Lamiids1. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard.. 2020;105(3):323-376.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Complete chloroplast genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of two dracocephalum plants. Biomed Res. Int.. 2020;2020:1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asterid Phylogenomics/Phylotranscriptomics uncover morphological evolutionary histories and support phylogenetic placement for numerous whole-genome duplications. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2020;37(11):3188-3210.

- [Google Scholar]