Translate this page into:

Inhibition of SARS-CoV2 viral infection with natural antiviral plants constituents: An in-silico approach

⁎Corresponding authors at: Department of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, AlMaarefa University, Dariyah, 13713, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (S.M.B. Asdaq), Krupanidhi College of Pharmacy, #12/1, Chikkabelandur, Carmelaram Post, Varthur Hobli, Bangalore-560035, India (P. Das). paramitadas04@gmail.com (Paramita Das), sasdag@mcst.edu.sa (Syed Mohammed Basheeruddin Asdaq), sasdaq@gmail.com (Syed Mohammed Basheeruddin Asdaq),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Background and Objective

In 2019, a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV-2) was declared pandemic. Advancement in computational technology has provided rapid and cost-effective techniques to test the efficacy of newer therapeutic agents. This study evaluated some of the potent phytochemicals obtained from AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa, and Homeopathy)-listed medicinal plants against SARS-CoV-2 proteins using computational techniques.

Materials and methods

The potential SARS-CoV-2 protein targets were utilized to study the ligand–protein binding characteristics. The bioactive agents were obtained from ashwagandha, liquorice, amla, neem, tinospora, pepper, and stevia. Ivermectin was utilized as a reference agent to compare its efficacy with phytochemicals.

Results

The computational analysis suggested that all the bioactive components from the selected plants possessed negative docking scores (ranging from −6.24 to −10.53). The phytoconstituents were well absorbed, distributed in the body except for the CNS, metabolized by liver enzymes, well cleared from the body, and well tolerated. The data suggest that AYUSH-recommended plants demonstrated therapeutic efficacy against SARS CoV-2 virus infection with significantly reduced toxicity.

Conclusion

The phytoconstituents were found to hinder the early stages of infection, such as absorption and penetration, while ivermectin prevented the passage of genetic material from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Additional research involving living tissues and clinical trials are suggested to corroborate the computational findings.

Keywords

COVID-19

Antioxidant

Molecular docking

Pharmacokinetics

Toxicity

Natural product

1 Introduction

Pandemics are one of the major reasons for devastating human health, including infections caused by viruses, bacteria, and fungi. A virus is a submicron parasite that resides in the host cell. The viruses either contain RNA or DNA but not both (Domingo, 2020).

The pandemic began to spread coronaviruses from the Coronaviridae family in the early twenty-first century (Davidson, 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Jeffrey and Kenneth, 2005). Coronavirus contains an RNA genome in its capsid, which contains spike proteins that are the main cause for the binding of the virus to host cells (Boopathi et al., 2021). A coronavirus variant named severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was discovered in humans in 2002. Later in 2012, a mutated variant of influenza that also had similarities with coronavirus was identified as MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia (Shereen et al., 2020). In 2019, the coronavirus came with a much superior mutant, namely Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 was also identified as Corona virus-induced disease 2019 (COVID-19), which started earliest in Wuhan, China, in November. The mutation in spike proteins on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 has a greater affinity to bind with angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE-II) than SARS-CoV. The spike proteins are present as a trimer in mature viruses, which helps in the entry of the virus into the cell (Xie et al., 2020). The S1 of SARS-CoV-2 RBD recognizes most of the sites in ACE-2, as it is only present in a lying-down position that helps in enhanced binding to ACE-2 (Shang et al., 2020). On entering the cell, the proteases activate the virus and infect the cell. The discovery of medicines and vaccines began as the virus spread, but only a few of them showed a positive response in treating the virus. As the virus became resistant to the drugs, several mutated forms such as alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and omicron evolved.

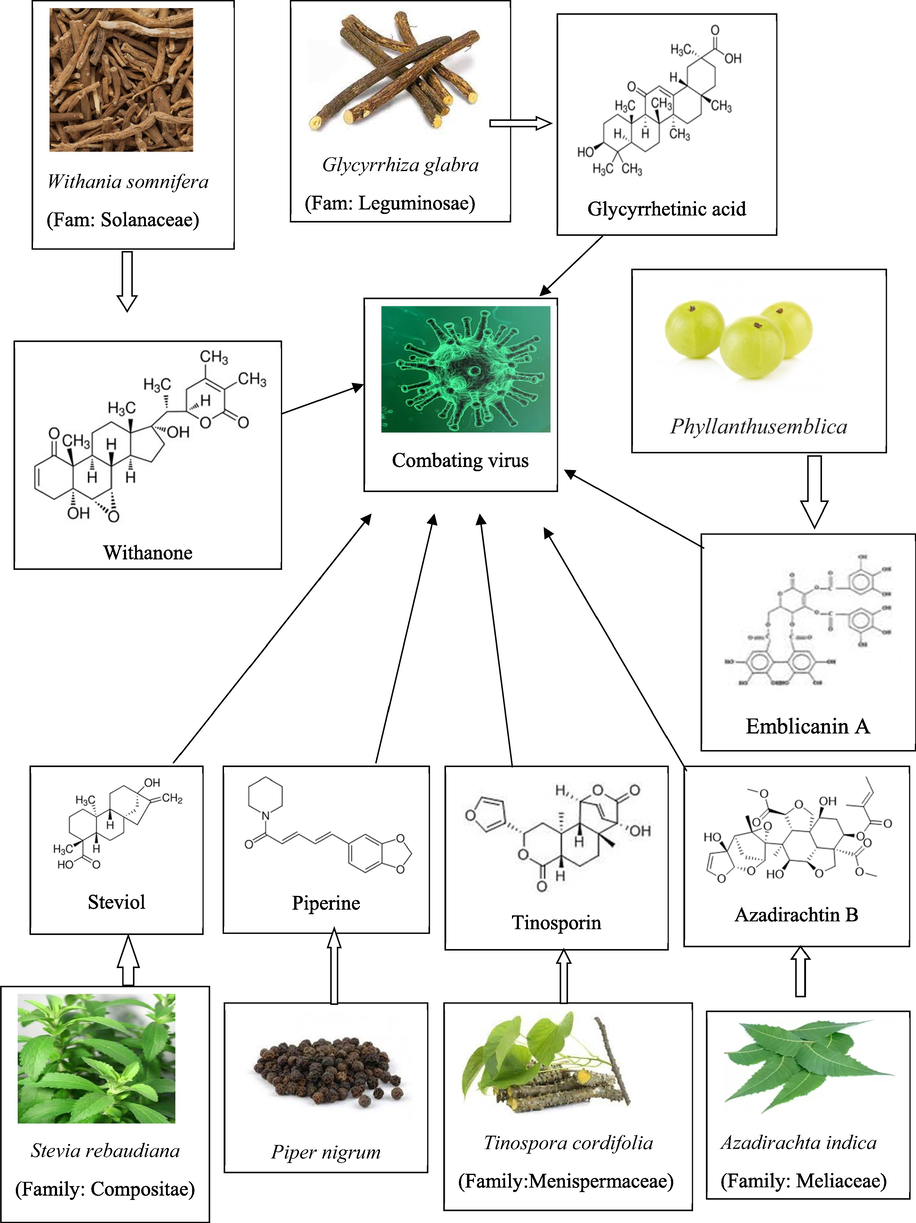

Recently, many scientific studies have revealed anti-viral activity with some specific natural plants, especially against the COVID virus (Ahmad et al., 2022; Das, 2022; Gezici and Sekeroglu, 2020). Natural plants demonstrated a positive effect on COVID control through physiochemical actions such as anti-mutagenic, anti-viral, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties. Herbal plants have low toxic substances that help with high intake and minor side effects (Umar et al., 2021). In daily life, a human consumes a lot of plant material in the form of food, through which immunity is easily acquired for various diseases, including COVID (Borse et al., 2021). The Indian Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa, and Homoeopathy (AYUSH) has recommended several important medicinal plants that have a significant impact in combating viral infections, particularly SARS-CoV-2. The selected plants are Withania somnifera, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Phyllanthus emblica, Azadirachta indica, Tinospora cordifolia, Piper nigrum and Stevia rebaudiana. All the listed plants contain potent bioactive compounds that have versatile therapeutic as well as medicinal properties. A literature survey revealed that withanone in Withania somnifera belongs to the Solanaceae family, shows potent antiviral activity (Kumar et al., 2022). Further, glycyrrhetinic acid from Glycyrrhiza glabra (F: Leguminosae) reported its potent antiviral activity (Huan et al., 2021) and emollicanin A from amla fruit (F: Phyllanthaceae) showed highly potent antiviral effects (Kar et al., 2022). Additionally, azadirachtin B from neem tree (F: Meliaceae) showed remarkable effects in combating viral infection (Baildya et al., 2021), and tinosporin from Tinospora cordifolia (F: Menispermaceae) demonstrated both antiviral agent and immunomodulatory properties (Khan and Rathi, 2020). Piperine from Piper nigrum (Family: Piperaceae) has recently been shown to have potent antiviral activity in addition to strong immunomodulatory potential (Nag and Chowdhury, 2020). Finally, steviol from Stevia rebaudiana (F: Asteraceae) shown to have potent antiviral activity (Peteliuk et al., 2021).

Therefore, it was our interest to determine the anti-COVID-19 capabilities of those plants and their bioactive constituents, which have been demonstrated to possess antiviral effects in different studies and listed in the medicinal plant list of the AYUSH department. The goal of this study was to compare the anti-COVID potential of the above-mentioned plants and their major bioactive constituents to standard Ivermectin using an in-silico method.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Selection of target and ligand

In the study, 7 potential targets of SARS CoV-2 were selected. 3D structural models of 6LZG (ACE2, SpS1 pro), 4TWW (3CL pro), 7AEH (3CL pro, Nsp5), 5S2T (Nsp3 pro), 7KZA (HCAb, LCAb), 7KVL (M pro), and 6 W63 (3CL pro) were acquired from the RCSB PDB (protein data bank) in PDB format. Prior to docking, energy minimization was performed by using MOE 2018 (molecular operating environment), water and ligand molecules were also removed before minimization. Ivermectin was used as a standard drug (Popp et al., 2021). Ligands were selected from literature studies based on antiviral properties. The chemical constituents in Ashwagandha (Withanone) (Dhanjal et al., 2021), Liquorice (Glycyrrhetinic acid) (Maddah et al., 2021), Amla (Emblicanin A) (Murugesan et al., 2021), Neem (Azadirachtin B) (Adegbola et al., 2021), Tinospora (Tinosporin) (Saha and Gosh, 2013), Black pepper (Piperine) (Lee et al., 2020), and Stevia (Steviol) (Das 2022) was used as a ligand that were effective against viral infections (Fig. 1). The structures of ligands were obtained from the ZINC15 database in SDF format. The online structure file generator tool from the national cancer institute is used to convert SDF format to PDB format. The biological sources, 2D structure, and ligand ID along with the docking score are mentioned in Table 1.

The phytochemical constituents with biological source used for the computational study.

Phytochemicals/ Repurposed drugs

Biological Source

3d and 2D structure with ZINC ID

Docking Score

(Kcal/mol)

PBD ID:6LZG

Ivermectin

(Standard)Streptomyces avermitilis

ZINC238808778−4.67

Withanone

(Compound A)Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera)

ZINC42876996−7.67

PDB ID:4TWW

Ivermectin

(Standard)Streptomyces avermitilis

ZINC238808778−7.39

Glycyrrhetinic acid

(Compound B)Liquorice

(Glycyrrhiza glabra)

ZINC19203128−7.55

PDB ID:7AEH

Ivermectin

(Standard)Streptomyces avermitilis

ZINC238808778−7.28

Emblicanin A

(Compound C)Amla (Phyllanthus emblica)

ZINC85664941−10.53

PDB ID:5S2T

Ivermectin

(Standard)Streptomyces avermitilis

ZINC238808778−6.08

Azadirachtin B

(Compound D)Neem (Azadirachta indica)

ZINC49841184−9.94

PDB ID:7KZA

Ivermectin

(Standard)Streptomyces avermitilis

ZINC238808778−6.26

Tinosporin

(Compound E)Tinospora cordifolia

ZINC4097885−7.13

PDB ID:7KVL

Ivermectin

(Standard)Streptomyces avermitilis

ZINC238808778−6.02

Piperine

(Compoud F)Piper nigrum

ZINC1529772−6.24

PDB ID:6W63

Ivermectin

(Standard)

Streptomyces avermitilis

ZINC238808778−6.2

Steviol

(Compound G)Stevia rebaudiana

ZINC6491272−6.9

2.2 Docking studies

The docking studies were conducted using AutoDock 4.2. Docking is used to predicting the binding interaction between protein and ligand, which gives specific activity. The binding interaction defines the basic biochemical processes based on the behaviour of the ligand at the site of a protein. At the end of docking studies, a docking score is obtained which determines the binding affinity of the target and ligand. The more negative is the docking score, the better the binding affinity and the greater the positive docking score, the weaker the binding activity. Discovery Studio 2021 was used for the visualization of the interaction between ligand and target. The obtained docking scores are compared with the docking score of standard ivermectin on the target.

2.3 ADMET studies

ADMET studies were performed by using pkCSM which depicted the values of parameters for different ligands, which were further compared with the standard Ivermectin.

3 Results

3.1 Molecular docking analysis

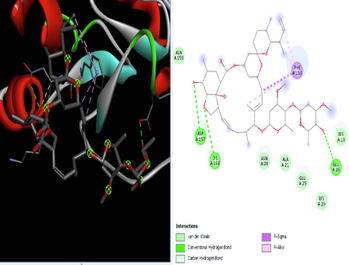

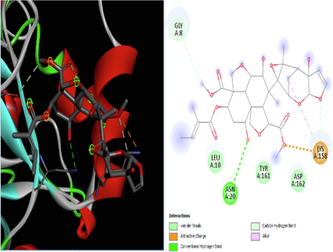

In the present study, 7 medicinal plants were selected, and a chemical constituent from each plant with antiviral properties was docked with SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Ivermectin was used as a reference drug and docked with all the proteins used in this study, as it was approved by the FDA for treating COVID-19. 6LZG was docked with ligand A (withanone), 4TWW was docked with ligand B (glycyrrhetinic acid), 7AEH was docked with ligand C (emblicanin A), 5S2T was docked with ligand D (azadirachtin B), 7KZA was docked with ligand E (tinosporin), 7KVL was docked with ligand F (piperine), and 6 W63 was docked with ligand G (steviol), and each of these proteins was docked with ivermectin, respectively. The binding energies of the phytochemicals and the control drug are depicted in Table 1. The docking scores for the different proteins were found to be 6LZG (Ivermectin = − 4.67, Withanone = −7.67), 4TWW (Ivermectin = −7.39, Glycyrrhetinic acid = −7.55), 7AEH (Ivermectin = −7.28, Emblicannin A = −10.53), 5S2T (Ivermectin = −6.08, Azadirachtin B = −9.94), 7KZA (Ivermectin = −6.26, Tinosporin = −7.13), 7KVL (Ivermectin = −6.02, Piperine = −6.24), and 6 W63 (Ivermectin = −6.2, Steviol = −6.7).

3.2 ADMET studies

For the development and discovery of new drugs, absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination, and toxicity play a significant role. The SMILES format of ligands was used to predict their properties. The study evaluated water solubility, intestinal absorption, CNS permeability, LD50, hepatotoxicity, etc., which are depicted in Table 2. All tested phytochemical ligands scored negative values for the water solubility characteristics, and the highest (−4.22) was found to be for ligand B (Glycyrrhetinic acid). The Caco2 permeability was found to be positive for all ligands except ligand C (Emblicannin A). The intestinal absorption was found to be 100 % for ligand B (Glycyrrhetinic acid) and the lowest was observed with ligand C (Emblicannin A). All ligands showed p-glycoprotein substrate activity except ligand E (Tinosporin) and ligand G (Steviol). The highest VDss value (0.875) was observed for ligand D (Azadirachtin B) and the lowest (−1.004) was for ligand B (Glycyrrhetinic acid). Note: Ligand A – Withanone, ligand B – Glycyrrhetinic acid, ligand C – Emblicannin A, ligand D – Azadirachtin B, ligand E – Tinosporin, ligand F – Piperine and ligand – Steviol.

ADMET properties

Ivermectin

Ligand

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

ABSORPTION

Water solubility

−4.33

−3.91

−4.222

−2.892

−3.47

−3.917

−3.464

−2.907

Caco2 permeability

0.577

0.982

1.053

−0.711

0.987

1.219

1.596

1.347

Intestinal absorption (human)

79.159

96.061

100

66.526

86.595

98.005

94.444

98.759

P-glycoprotein substrate

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

No

DISTRIBUTION

VDss (human)

0.64

0.46

−1.004

0.002

0.875

0.243

0.158

−0.942

CNS permeability

−3.416

−2.818

−1.017

−6.199

−3.094

−2.923

−1.879

−0.134

METABOLISM

CYP3A4 substrate

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

CYP2C19 inhibitor

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

No

CYP2C9 inhibitor

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

No

No

CYP3A4 inhibitor

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

EXCRETION

Total Clearance

0.533

0.381

−0.114

0.641

0.263

0.689

0.232

0.507

Renal OCT2 substrate

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

TOXICITY

AMES toxicity

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

Max. tolerated dose (human)

−1.288

−0.569

0.741

0.438

−0.446

−0.314

−0.38

−0.141

hERG II inhibitor

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

Oral Rat Acute Toxicity (LD50)

3.706

2.806

3.824

2.481

3.339

2.819

2.811

1.954

Hepatotoxicity

Yes

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

All ligands except ligand C (Emblicannin A) and ligand D (Azadirachtin B) exhibited CYP3A4 substrate activity. The ligands F (piperine) and C (embrlicannin A) inhibited CYP2C19 and CYP2C9, respectively. The highest total clearance (0.689) was found with ligand E (Tinosporin) and the lowest (−0.1114) with ligand B (Glycyrrhetinic acid). Renal OCT2 substrate was found with three ligands, such as ligand A (Withanone), ligand C (Emblicannin A) and ligand F (Piperine).

None of the tested ligands exhibited AMES toxicity potential. The maximum tolerated dose was found to be highest (0.741) for ligand B (Glycyrrhetinic acid), highest oral rat acute toxicity (LD 50) value was observed with ligand D (Azadirachtin B); and two ligands (Piperine and Steviol) showed hepatotoxicity potential.

The ligands' molecular properties are listed in Table 3. The highest molecular weight was found with ligand C (Emblicannin A). The highest log P value for ligand B (Glycyrrhetinic acid), more rotatable bonds in ligand D (Tinosporin), more acceptor ability with ligand C (Emblicannin A), and donor property in ligand C (Emblicannin A). Note: Ligand A – Withanone, ligand B – Glycyrrhetinic acid, ligand C – Emblicannin A, ligand D – Azadirachtin B, ligand E – Tinosporin, ligand F – Piperine and ligand – Steviol.

Molecular properties

Ivermectin

Ligands

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

Molecular weight

875.1

470.6

470.6

782.5

662.6

358.3

285.3

318.4

Log P

5.60

3.49

6.41

1.36

−0.09

2.53

2.99

4.155

Rotatable bonds

8

2

1

4

5

1

3

1

Acceptor

14

6

3

22

14

6

3

2

Donors

3

2

2

12

3

1

0

2

4 Discussion

According to the literature, herbal medicines have been used since ancient times in the treatment of multiple health hazards, including a vast number of infectious diseases (Siddique et al., 2021). Following the completion of the preclinical and clinical evaluations, several of them are commercially marketed. These components are gaining popularity, being derived from nature, they are devoid of serious adverse effects and have been reported to cure the disease by treating the root cause (Singh et al., 2020). As a result, it is believed that any medicinal plant may serve as a potential source for the treatment of every disease, including viral infections (Aschale et al., 2021).

Diseases caused by infectious microorganisms present difficulties in treatment due to the quick development of resistance. Besides, the medications might interfere with the host cell's functioning, leading to the appearance of several adverse effects. Viruses made of either RNA or DNA complicate treatment because the organism rapidly modifies its structural components to develop resistance to therapeutic interventions (Davidson, 2021; Qin et al., 2021; Sulimov et al., 2021). Several medicinal plants have been shown to exhibit strong inhibition (in vitro) against viral replication, boosting the likelihood of discovering new bioactive plant chemicals (Severson et al., 2008). Based on this research, in the present study, ashwagandha, liquorice, amla, neem, tinospora, pepper, and Stevia were selected as per the AYUSH recommendation. As reported, the bioactive constituents of these selected plants have shown potent antiviral properties in in vitro studies. Withanone from Ashwagandha showed in vitro antiviral activity by targeting the viral main protease (MPro) and host transmembrane TMPRSS2 (Balkrishna et al., 2021). Also, embricanin A from Phyllanthus emblica reported the inhibitory activity of herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) and type-2 (HSV-2) (Chojnacka et al., 2021).

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) is currently-one of the most widely used approaches for drug development and discovery (Wang et al., 2018). The research suggests that docking studies can be performed on the phytochemicals of herbal plants. Docking studies were done using Autodock, which helps in depicting the required data. The herbal plants were selected based on their anti-viral properties and other pharmacological activities that were liable for blocking the entry of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) (Fallah et al., 2021).

According to the literature, docking studies are determined by hydrogen bonds, as they play a crucial role in docking. It was found that hydrogen bonds had a direct relationship with the binding energy (docking score). Based on this, the current study was conducted to determine the efficacy of the AYUSH-recommended plants against SARS CoV-2 viral infection using an in-silico docking study. Ivermectin has been approved by the FDA for clinical studies against SARS-CoV-2, which was used as a reference (Caly et a., 2020) for the present study and has shown less binding energy and less hydrogen bonding compared to the ligands such as A, B, C, E, F, and G (Table 1). The test compounds exhibited satisfactory pharmacokinetic properties and low toxicity potential compared to the reference drug (Table 2). The findings are consistent with previous findings that compounds with antiviral properties may be effective against SARS-CoV-2 (Caly et al., 2020).

In our study, a similar result was also recorded where emblicanin A (from Phyllanthus emblica) showed a higher binding affinity with a −10.53 (Sharma et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021), followed by Azadirachtin B (from Azadirachta indica) with a binding affinity of 9.94 when compared with the reference Ivermectin. Except for neem, all other herbal plants in the study showed better hydrogen bonding, but azadirachtin B acts as an adjuvant. Compared to all the test compounds, ligand C (emblicannin A) showed the best activity, which is a phytoconstituent of Amla. Interestingly, the Stevia plant also showed potent antiviral action by binding affinity with a value of −6.9 when docked with the steviol group, which was higher than piperine (−6.24) from Piper nigrum (piperine), although both piperine and steviol showed hepatotoxic potential (Tables 1 and 2). These findings support previous findings that compounds with high binding affinity for proteins have higher negativity in docking scores (Fallah et al., 2021).

5 Conclusion

In this study, molecular docking and ADMET studies were carried out for phytochemicals from important AYUSH-recommended herbal plants with SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Ivermectin was used as a controlled drug and was found to have less docking properties as well as hepatotoxic. In comparison, all the phytochemical ligands tested exhibited strong binding characteristics with SARS-CoV-2 proteins, but emblicannin A and azadirachtin B were found to be superior. The data suggest that the phytochemical constituents could be potential agents against SARS-CoV-2. However, more studies are needed to validate the potential of the compounds using both animal and clinical tests.

Funding

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R115) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors would like to acknowledge AlMaarefa University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for extending financial support to do this research.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R115) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors are thankful to the Management and Principal of Krupanidhi College of Pharmacy for the given facilities to conduct docking studies through software.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Molecular docking and ADMET studies of Allium cepa, Azadirachta indica and Xylopia aethiopica isolates as potential anti-viral drugs for COVID-19. Virus Dis.. 2021;32(1):1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive genomic study, mutation screening, phylogenetic and statistical analysis of SARS-CoV-2 and its variant omicron among different countries. J. Infect. Public Health. 2022;15(8):878-891.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic Review on Traditional Medicinal Plants Used for the Treatment of Viral and Fungal Infections in Ethiopia. J. Exp. Pharmacol.. 2021;13:807-815.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of potential drug from Azadirachta Indica (Neem) extracts for SARS-CoV-2: An insight from molecular docking and MD-simulation studies. J. Mol. Struct.. 2021;1227:129390

- [Google Scholar]

- Withanone from Withania somnifera Attenuates SARS-CoV-2 RBD and Host ACE2 Interactions to Rescue Spike Protein Induced Pathologies in Humanized Zebrafish Model. Drug Des. Devel. Ther.. 2021;15:1111-1133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel 2019 coronavirus structure, mechanism of action, antiviral drug promises and rule out against its treatment. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.. 2021;39(9):3409-3418.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ayurveda botanicals in COVID-19 management: An in silico multi-target approach. J. Plus One.. 2021;16(6):e0248479.

- [Google Scholar]

- The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antivir. Res.. 2020;178:104787

- [Google Scholar]

- Herbal plants as immunity modulators against COVID-19: A primary preventive measure during home quarantine. J. Herbal Med.. 2022;32:100501

- [Google Scholar]

- Viruses' evolvement as a never stopping perpetuum mobile. J. Virolog. Methods.. 2021;289(188):114037

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular mechanism of anti-SARS-CoV2 activity of Ashwagandha-derived withanolides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2021;184:297-312.

- [Google Scholar]

- Introduction to virus origins and their role in biological evolution. Virus Populat.. 2020;1–33

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular docking investigation of antiviral herbal compounds as potential inhibitors of sars-cov-2 spike receptor. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem.. 2021;11(5):12916-12924.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel SARS CoV-2 and COVID-19 outbreak: current perspectives on plant based antiviral agents and complementary therapy. Ind. J. Pharma. Edu. Res.. 2020;54(3):S442-S456.

- [Google Scholar]

- Research Progress on the Antiviral Activity of Glycyrrhizin and its Derivatives in Liquorice. Front. Pharmacol.. 2021;12:680674

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- History and Recent Advances in. Corona virus Discovery. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis.. 2005;24(11):S223-S227.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of phytocompounds as newer antiviral drugs against COVID-19 through molecular docking and simulation based study. J. Mol. Graph. Model.. 2022;114:108192

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tinospora Cordifolia-An immunomodulatory drug in Ayurveda for prevention and treatment of Covid-19. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci.. 2020;11(1):1695-1699.

- [Google Scholar]

- Withanone and Withaferin-A are predicted to interact with transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) and block entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.. 2022;40(1):1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and antioxidant capacity of black pepper pericarp. ApplBiol Chem.. 2020;63(35)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Proposing high-affinity inhibitors from Glycyrrhiza glabra L. against SARS-CoV-2 infection: virtual screening and computational analysis. New J. Chem.. 2021;45(35):15977-15995.

- [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan, S., Kottekad, S., Crasta, I., Sreevathsan, S., Usharani, D., Perumal, M.K., Mudliar, S.N., 2021. Targeting COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) main protease through active phytocompounds of ayurvedic medicinal plants - Emblica officinalis (Amla), Phyllanthus niruri Linn. (Bhumi Amla) and Tinospora cordifolia (Giloy) - A molecular docking and simulation study. Comput. Biol. Med. 136, 104683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104683.

- Piperine, an alkaloid of black pepper seeds can effectively inhibit the antiviral enzymes of Dengue and Ebola viruses, an in silico molecular docking study. Virus Disease.. 2020;31(3):308-315.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural sweetener Stevia rebaudiana: Functionalities, health benefits and potential risks. EXCLI J.. 2021;20:1412-1430.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ivermectin for preventing and treating COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2021;7(7):CD015017.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) targets and mechanisms of puerarin. J. Cell Mol. Med.. 2021 Jan;25(2):677-685.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-throughput screening of a 100,000-compound library for inhibitors of influenza A virus (H3N2) J. Biomol. Screen.. 2008;13:879-887.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2020;117(21):11727-11734.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of natural inhibitors against prime targets of SARS-CoV-2 using molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation and MM-PBSA approaches. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J. Adv. Res.. 2020;24(16):91-98.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Medicinal plants used to treat infectious diseases in the central part and a northern district of Bangladesh – An ethnopharmacological perception. J. Herb. Med.. 2021;29:100484

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of herbal plants in prevention and treatment of parasitic diseases. J. Sci. Res.. 2020;64(1):50-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-silico analysis of the inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease by some active compounds from selected African plants. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci.. 2021;16(2):162-176.

- [Google Scholar]

- A human monoclonal antibody blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun.. 2020;11(1):2251.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of Drug Binding Sites and Action Mechanisms with Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Curr. Top. Med. Chem.. 2018;18(27):2268-2277.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spike Proteins of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 Utilize Different Mechanisms to Bind With Human ACE2. Front Mol. Biosci.. 2020;7:591873

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolomics and in silico docking-directed discovery of small-molecule enzyme targets. Anal. Chem.. 2021;93(6):3072-3081.

- [Google Scholar]