Influence of nanoparticles on food: An analytical assessment

⁎Corresponding author. sasdeky@kku.edu.sa (Sazada Siddiqui),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Nanotechnology is a novel frontier transforming traditional food sector into an emergent, dynamic and innovative food industry. The swift advancement of nanotechnology has been expediating the alterations of conventional food principally the creation of elegant and vibrant packaging and for betterment of quality of food and its safety, various new nanomaterials have been created. Advances in nano-packaging, nano-biosensors, and nanofood are the foremost recent progressions of nanoscience. Technology based on nanoscience has a vital impact on the quality, safety, and packing of food materials. Nanotechnology application enables preservation of food, increases shelf life, and facilitates nutrition enrichment. In spite of the enormous benefits of nanotechnology, there are vital concerns regarding its usage; since the accumulation of nanoparticles (NPs) in human beings and environment can result in various safety and health hazards.

In the present article, current trends in nanotechnology are examined, and the utmost difficult tasks and favorable prospects in the food sectors are focused. The toxicological basics and risk evaluation of nanomaterials in these novel foods are also reviewed. For balanced and sustainable advancement, the possible use of bio-inspired and biosynthesized nanomaterials is emphasized. Though, vital queries regarding higher performing, lesser noxious nanomaterials should be focused to enable dynamic progress and use of nanotechnology. In order to manage the usage, production, handling, treatment, and discarding of nanomaterials; legislation and regulation are of great importance. To reinforce awareness among public and acknowledgement of the new nano-enabled foods, hard work needs to be done. In conclusion, nanotechnology proposes an overabundance of prospects, by delivering a new and workable substitute in the food industry.

Keywords

Nanoparticles

Nanomaterials

Nanotechnology

Food

Food safety

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology is altering our whole social order and it is extensively used in our daily life. Novel methodologies of nanotechnology in food industry, the utmost current progresses made in the domain of nanostructured constituents that have substantial influence on the food sector. Since, the present food segment demands modernization, nanotechnology combined with novel interdisciplinary methods and processing procedures has empowered significant developments capable of transforming the food industry. Nanotechnology can help to determine tasks confronted by the food and bioprocessing companies for progressing and executing systems that can yield quantitative and qualitative foods that are viable, harmless, and biodegradable. After the Department of Agriculture of United States printed the first ever roadmap in September 9, 2003 nanotechnology has started stepping in food industry (US DOA, 2003). During the last decade, research work on this subject has risen steeply. It nearly covered every single aspect in the food industry including packing and processing of food. (Christopher et al., 2021; Silvana et al., 2020; Xiaojia et al., 2019; Dasgupta and Ranjan, 2018).

The beverage and food segment are a worldwide multi trillion-dollar business (Xiaojia et al., 2019; Cushen et al., 2012). By the year 2020, a current evaluation of the universal economic effect of nanotechnology is anticipated to be at least $3 trillion. Globally, this may operate 6 million labors in the expanding nanotechnology trade (Roco et al., 2011). It has motivated several food companies occupied in the progress and promotion of innovative nanomaterial centered foods and shooting up manufacturing competence, safety, taste, and various features of food. Incredibly, there are hundreds of products that have already been marketed and used in the food business. During the last decade, there are more than hundreds of foods that have been promoted and consumed in the food industry. With an exception to iron oxide and titanium dioxide which have been used as colorant and food pigment respectively, neither a single nanomaterial comprising products have been put into the food used by humans. The essential cause is that legislation and regulation is restricted concerning nano food, particularly because of the intricacy of nanomaterials and legislating processes (Kumar et al., 2020; Daniela et al., 2019).

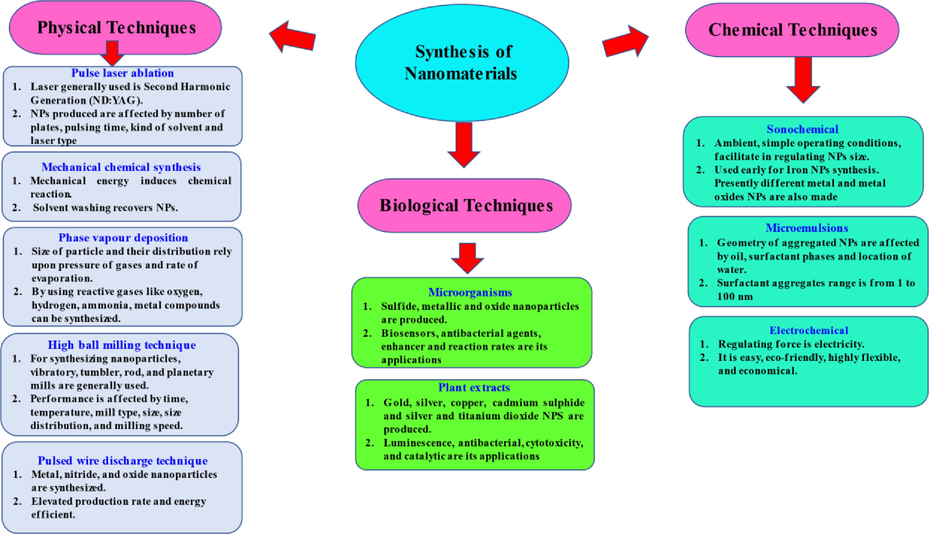

2 Nanomaterial synthesis

Nanomaterials having one dimension varying from 1 to 100 nm are covered in Nanotechnology. Various techniques are accessible for synthesizing several kinds of nanomaterials in form of colloids, particles, powders, tubes, clusters, rods, wires, and thin films. The synthesis techniques are categorized in three prime techniques (physical, chemical, and biological) for synthesis of nanomaterials as depicted in the self-explanatory (Fig. 1). The technique created is upon the basis of the kind of nanostructures like nanowires, nanoplates, quantum dots, and nanorods.

-

Physical techniques: Evaporation and mechanical forces are normally used in synthesizing nanomaterials. Some physical techniques used for synthesizing nanomaterials are mechanical chemical synthesis, pulse laser ablation, physical vapor deposition through consolidation, high ball milling, and pulsed wire discharge method (Ubaidullah et al., 2020a; Ameta et al., 2020).

-

Chemical techniques: Chemical techniques have few benefits over physical like synthesis at a low temperature of less than 350 °C, potential of making different shapes and sizes of nanoparticles, simple transition of end products in liquid form to thin films or dry powder, and possibility of assimilation of iron atoms while synthesis (Mateja et al., 2021; Al-Enizi et al., 2020a; 2020b;; Ubaidullah et al., 2020b). The chemical techniques are sonochemical, microemulsion, and electrochemical (Monalisa et al., 2021).

-

Biological techniques: The benefits of synthesizing nanomaterials by using biological techniques are simple scaling-up, nontoxicity, ecofriendly, reproducibility in making, and distinct morphology. The biological techniques involve the synthesis of nanoparticles by microorganisms like yeasts, bacteria, fungi and by plant extracts. (Yogita et al., 2021; Shivraj et al., 2020; Singh, 2016).

- Synthesis of Nanomaterials.

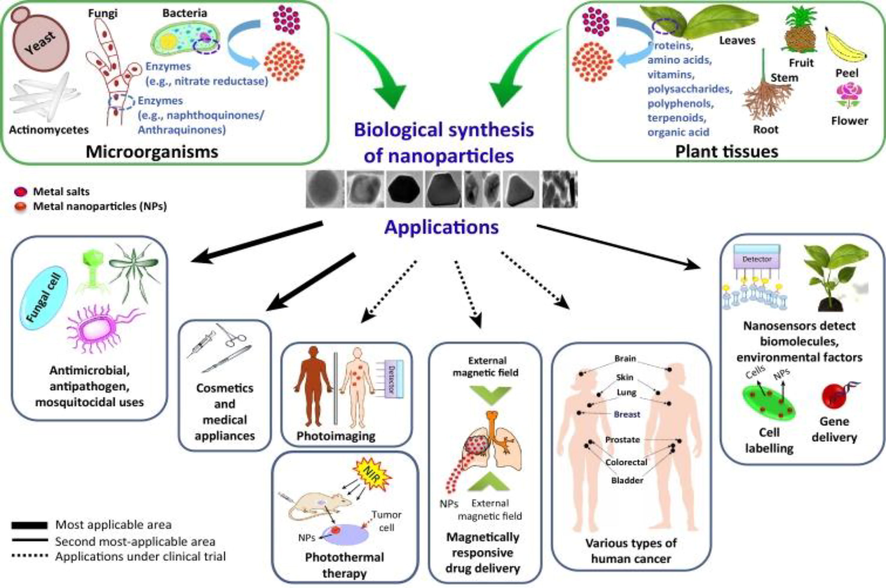

3 Biosynthesized nanoparticles

For viable and green environment friendly chemistry process, biosynthesis has become a recent trend for the advancement and design of various NPs (Fig. 2). Several parts of plants for example fruits, roots, leaves, and their extracts and various biological organisms including fungi, yeast, enzymes, bacteria, and actinomycetes have exhibited assuring appropriateness for the biosynthesis of NPs as listed (Table 1).

- Biotic synthesis and NPs application. Reproduced with permission from Singh et al. (2016a).

| Biological model | Biogenic nanoparticles | Classification | Characteristics | Note | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aquatic algae | |||||

| Brown alga Cystoseira trinoids | CuO nanoparticles | XRD, TEM (7-10 nm), Raman, FE-SEM (6-7, 8 nm), EDX, AFM | Antioxidant, antibacterial and catalytic in nature | Stabilizing and reducing | (Gu et al., 2018) |

| Macroalga Sargassum muticum | ZnO nanoparticles | FESEM, FTIR, XRD, 30- 57 nm, UV- vis | Not applicable | (Azizi et al., 2014) | |

| Plant extracts | |||||

| Root of red ginseng | Silver and gold nanoparticles | EDX, UV-vis, TEM (10-30 nm) | Antimicrobial action | Stabilizing and reducing | (Singh et al., 2016b) |

| Seeds of Coffee Arabica | Silver nanoparticles | FTIR, DLS (20-30 nm), UV-vis, TEM, XRD, SEM-EDXA | Mic ≤ 0.2675 mg/L on S. aureus and E. coli | (Dhand et al., 2016) | |

| Leaf of Cassia tora | Silver nanoparticles | SEM, FTIR, EDAX and XRD | Antibacterial and antioxidant actives | Plant extract is used as a reducing agent | (Adio et al., 2017) |

| Aloe vera | Nanoscale zero-valent iron | EDS, FTIR, TGA, FESEM and XRD | Elimination of arsenic and selenium from water | Plant extracts is used as a reducing agent | (Saravanakumar et al., 2015) |

| Leaf of Atrocarpus altilis | Silver nanoparticles | FTIR, XRD, EDX, SEM (34 nm), TEM (38 nm) and DLS (162.3 nm) | Antioxidant and antimicrobial | Phyto ingredients as capping agent | (Ravichandran et al., 2016) |

| Leaf of Nigella sativa | Silver nanoparticles | SEM 15, nm, UV-vis, FTIR | Lesser cytotoxicity and phytotoxicity than wet –chemistry synthesis ones (30 nm) | Extract of plant is used as capping and reducing agent | (Amooaghaie et al., 2015) |

| Oranges and Pineapples | Silver nanoparticles | SEM (10-300 nm), UV-vis | Not applicable | Reducing agent | (Hyllested et al., 2015) |

| Leaf of Butea monosperma | Silver and gold nanoparticles | XRD, TEM, XPS, FTIR, DLS, UV-vis | Inhibition of cancer cell creation | Extract of plant is used as reducing, stabilizing /capping agent | (Patra et al., 2015) |

| Bark of Butea monosperma | Silver nanoparticles | TEM, FTIR, XRD, EDX and DLS (98.28 nm) | Antibacterial action and cytotoxic impact on human myeloid leukemia cell line. | Capping and reducing agent | (Pattanayak et al., 2017) |

| Fruit of Longan | Silver nanoparticles | TEM (4-10 nm), XRD, EDX, FTIR, UV-vis | Enzymatic browning reduction on white cabbage. MIC .31.25 µg/ml against Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtills, 62.5 µg/ml against E.coli | Reducing, stabilizing /capping agent | (Khan et al., 2016) |

| Bacteria | |||||

| Serratia sp. BHU-S4 | Silver nanoparticles | XRD, EDXA, FTIR and TEM (10-20 nm) | Used as fungicide against phytopathogen bipllaris sorokiniana instigating spot blotch disease in wheat plants | Stabilization and reduction | (Mishra et al., 2014) |

| Pichia fermentans JA2 | Zinc oxide and silver nanoparticles | XRD, UV-vis, and FE-SEM-EDX analysis | Silver NPs contained majority of the G-clinical pathogens; ZnO nanoparticles contained only Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Synergistic effect exhibited with antibiotics | (Chauhan et al., 2015) |

| Bacillus cereus srtain HMH1 | Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles | FT-IR, 29.3 nm .FE-SEM, DLS,, EDS UV-vis, and VSM | Lesser cytoticity: IC50 MCF7->5 mg/ml and IC50, 3T3> 7.5mg/ml | Stabilizing and capping agent | (Fatemi et al., 2018) |

| Fungi | |||||

| Aspergillus flavus TFR 7 | TiO2 nanoparticles | EDX, DLS, TEM (12-15 nm) | Stimulate plant G root length (%49.6+) shoot length (%17+) root area (%43+) and root nodules (%67.5+) Encourage rhizosphere microbes | From rhizosphere soil, fungi is isolated | (Raliya et al., 2015) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Silver nanoparticles | FTIR, UV-vis, XRD, TEM | Photocatalytic degeneraytion of methylene blue | Biomolecules act as capping and reducing agent | (Roy et al., 2015) |

| Aspergillus flavus and Emericella nidulans | Silver nanoparticles | FTIR, EDX, Hexagonal-and triangular-shaped DLS (36-531 nm, 37-340 nm), XRD TEM (30-150 nm, 10-450 nm) | Antibiofilm and synergistic antibacterial action | Capping and reducing agent | (Barapatre et al., 2016) |

| Yeast | |||||

| Candida lusitaniae | Silver chloride / silver nanoparticles | SEM-EDS, FIB/SEM, UV-vis, XRD, TEM | Antimicrobial action | From gut of termite, yeast is isolated | (Eugenio et al., 2016) |

| Magnusiomyces ingens LH-F1 | Gold nanoparticles | FTIR, SEM, UV-vis, SDS-PAGE, DLS, TEM | Catalytic reducing of nitrophenols | Reducing, stabilizing /capping agent | (Zhang et al., 2016) |

| Rhodotorula glutinis and Cryptococcus laurentii | Silver nanoparticles | FTIR, UV-vis, TEM (15-220 nm), XRD | Antifungal action against Phytopathogenic fungi (Aspergillus niger, Penicillium expansum, Botrytis cinerea, Rhizopus and Alternaria species) | From apple peel yeast is isolated | (Fernández et al., 2016) |

| Actinomycetes | |||||

| Strain NH21 of Streptomyces | Gold and silver nanoparticles | UV-vis, FTIR, AFM, TEM | Antibacterial action | Capping agent, isolated from acidic soil | (Składanowski et al., 2017) |

| Isolated VITBN4 | CuO nanoparticles | XRD (61.7 nm), TEM (61.7 nm) DLS (198 nm), FTIR, EDX, SEM, UV-vis | Antibacterial action against fish and human bacterial pathogens | Stabilization, reduction and capping agent, isolated from soil sample | (Nabila and Kannabiran, 2018) |

| Enzymes | |||||

| Alpha amylase | TO2 nanoparticles | FTIR, XRD, TEM | MIC of 62.5 µg/ml Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcous aureus | Enzyme is used as capping and reducing agent | (Ahmad et al., 2015) |

XRD = X-Ray Diffraction; TEM = Transmission electron microscopy; EDX = Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis; SEM = Scanning electron microscope; AFM = Atomic force microscopy; UV–Vis = Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy; FTIR = Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy; FESEM = Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope; AFM = Atomic force microscopy; EDS or EDAX = Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis.

Most of the researchers have stated three important benefits:

-

in order that a lesser number of hazardous substances will be utilized through the engineering procedures, biological system as producing host can act as reducing, capping and stabilizing agent.

-

the usage of unsafe chemicals and resources for energy gets alleviated by biosynthesis which often takes place in neutral pH and ambient pressure and temperature.

-

because of the surface functionalization throughout the biosynthesis procedure, majority of the biosynthesized nanoparticles are less toxic and biocompatible.

As a replacement for applying chemical capping, reducing, and stabilizing agents, biological systems can perform as operative elements. Previous researches have shown that macrobiomolecules for example lipids and proteins having operative carboxyl and amide groups could be adsorbed on the surface of NPs, that means it might be participating in the stabilization of Au NPs (Christopher et al., 2021; Silvana et al., 2020). Moreover, the function of biomolecules in nanomaterial synthesis as capping agent is reported in many studies (Table 1). Furthermore, for biological systems; neutral pH, ambient pressure, and temperature are the normal requisites. Chemical synthesis of nanomaterials is frequently done and is often carried out at extreme pH and high pressure, temperature (Mateja et al., 2021; Monalisa et al., 2021).

4 Recent status on food nanotechnology

In food industry, tested nanomaterials comprise of organic (natural product nanoparticles), inorganic (metal and metal oxide nanoparticles) and both organic and inorganic for example clay. Amongst all metal nanoparticles, gold nanoparticle is generally considered as a detector/sensor whereas silver nanoparticle because of its antimicrobial action is used mostly for commercial purpose. For flavor enhancing, disinfecting and food additives, titanium dioxide nanoparticles are widely applied. Natural product nanoparticles are used as constituents or enhancements in food industry (Yogita et al., 2021; Monalisa et al., 2021)

Various NPs have revealed great possibility and capability in every single phase of food industry and agriculture. Within several facets of consumer goods, food nanotechnology has penetrated for example food conservation, packing and supplements or additives. In safeguarding of food safety, nanotechnology has progressed the food treatment and storing processes (Monalisa et al., 2021). On nanometer scale, various chemicals supplemented as food additives or packing ingredients have been found partly existing. For example, in the nanometer range, food-grade TiO2 NPs have been found up to roughly 40% (Dudefoi et al., 2017). Although TiO2 NPs are usually acknowledged as lesser toxic at ambient conditions, long-term contact to such NPs may cause unfavorable effects (Mateja et al., 2021; Dorier et al., 2017). Certain NPs applied in food products are listed (Table 2). The major bases for regulation and legislation are United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) and European Commission (EC) on food nanotechnology. On the basis of risk evaluation of the particle size of a substance, some authorizations are made by EC and U.S. FDA. Under research and development (R&D), a few applications are also comprised to designate possible future applications (Table 2).

| Nanoparticles used in processing of foods - A | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usage | Nanoparticles | Producer | Recent status | Comment | Reference |

| Color flavorings | Synthetic iron oxide TiO2 |

Relieved from permit Relieved from permit |

> 1% by food weight >0.25 (for cats and dogs) and 0.1 (human) % by complete food weight |

(CFR, 2018) (https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text) (U.S. FDA, 2015) (CFR, 2011) (https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text) |

|

| Additive Preservers Flavor carries Fruit and vegetables promotion Anticaking substances Nutritive dietetic enhancement |

Carbon black Titanium nitride Iron oxide Aluminum oxide Silicon dioxide Cobalt oxide MnO (E530) ZnO Silver -silica Silica dioxide (E551) Silica dioxide (E551) Silica dioxide (E551) Copper oxide Iron oxide Zno |

Nanox intelligent particles | Approved by EC 10/2011: not sanctioned by the U.S. FDA as additive Approved by EC 10/2011 FCS a inventory Approved by EC 10/2008 Relieved from permit REG b Generally recognized as safe |

No passage stated, to be used in PET Bottles only upto 20 mg/kg. > 2.5% w/w in the polymer Approval established on conservative dimensions of particles FCN NO. 1235 4 > ppm by silver weight blended into polymers as an antimicrobial agent >10,000 mg/kg, not including infant foods and foods for young children >2% of the solid ink >2% by food weight Approved for use as animal fodder |

(EU 2011) (U.S. FDA 2018) https://www.accessdata.fda.gov) Euroapen Commision. Regulation (EC, 2008) https://eur-lex. (CFR, 2017) (https:// www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-) (CFR, 2018) (https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text) (U.S. FDA 2018) https://www.fda.) |

| Nanoparticles food contact packing- B | |||||

| Usage | Nanoparticles | Producer | Recent status | Comment | Reference |

| Pesticides identification Pathogens identification |

Zinc Oxide QDs Fluorescent nanosensor Plasmonic nanosensors Magnetic nanosensors |

Generally recognized as safe Research and development |

(Sahoo et al. 2018) (Kearns et al. 2017)) (Banerjee et al. 2016) |

||

| Toxins identification | Phosphorescent QDs Plasmonic nanosensors |

Research and development |

(Sun et al. 2018) (Zhang et al. 2016) |

||

| Edible film/covering | Chitosan/Nano-Silica Covering Nanoemulsion/Quinoa Protein/ Chitosan Poly-ε-caprolactone Nanoemulsion with lemongrass essential oil Bio-nano-hybrid pectins and LDH salicylate Bentonite (Al2O3 4SiO2nH2O) |

Research and development (Generally recognized as safe) |

Test done on Longan fruit Test done on fresh strawberries Test made on fresh cut red delicious apples Test done on fresh –cut - Fuji apples Test made on fresh apricots Test done on fresh –cut - Fuji apples U.S. FDSA 21 CFR 184.1155 |

(Shi et al. 2013) (Robledo et al. 2018) (Zambrano-Zaragoza et al. 2014) (Salvia-Trujillo et al. 2015) (Gorrasi and Bugatti, 2016) (CFR 2018) https:// www.ecfr.gov/cgi- |

|

| Flame Retardation additive, gas barrier, etc. Prevent abrasive wear | Montmorillonite Montmorillonite chromium (iii) oxide Nanoemulsion with lemongrass essential oil |

Poly One corporation Nanocor ®inc. Toyo Seiken Kaisha Limited and Nanocor Incorporated. Oerlikon Balzers covering AG, Oerlikon surface solutions AG. |

FCS a inventory | FCN NO. 1163 FCN NO. 932. FCN NO. 1839. For usage at a thickness not exceeding 200 nm, not used in contact with human milk and infant formula. |

(U.S. FDA 2018) https://www.accessdata.fda.gov (Gorrasi and Bugatti, 2016) (Salvia-Trujillo et al., 2015) |

| Deter abrasive wear heat enhancer in Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) polymers | Titanium aluminum nitrite Tin antimony oxide |

Balzers Aktingeselleschaft Nyacol Nano Technologies, Inc |

(Generally recognized as safe) FCS a Inventory |

FCN NO. 302, The utmost thickness of the coating of surface must not exceed 5 µm. FCN NO. 1437. less than 0.05 by polymer weight |

(CFR 2018) https:// www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin) (U.S. FDA 2018) https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/) |

5 Usage of nanoparticles in processing of food

Nanomaterials are widely used as carriers for food enhancement for example nanoemulsion and nanoencapsulation, preservatives, feeding foods used for animals, flavors or color additives (Vivek et al., 2018). The exclusive features and properties of nanomaterials which are engineerable may pose excessive benefits for processing of food as constituents or additives. Inorganic oxide chemicals allowed by the U.S. FDA are MgO (E530), TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551) as food flavor carrier, food color additives and anti-caking agent (Table 2). In cake icing, puddings, candy, gum and white sauces TiO2 is extensively used as a food additive (Kumar et al., 2020). Apart from titanium nitride and carbon black, present permissions on the chemicals enumerated in (Table 2) for processing of food are on the basis of conventional particle size. Besides foods being directly supplied to human beings, animal feeds also constitute a substantial part in the worldwide food business, ensuring safe and cheap manufacturing of products used for animals all over the world. U.S. FDA has considered zinc oxide, copper oxide and iron oxide as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) nutritive dietary enhancement in animal feeds (Table 2 A).

6 Application of nanoparticles in food packaging

In food industry, nanotechnology has been broadly studied, established and industrialized for food packing as an innovative solution (Emamhadi et al., 2020; Daniela et al., 2019). During production, carriage and storing, food contact ingredients are meant to openly contact food produces. Nanomaterials intended for food packing enjoy various benefits as related to traditional packing material. Because of their thermal, mechanical and barrier properties and lower cost, nano clay is generally used for food packing.

Based on the physiochemical properties of the nanomaterials, nanoclays are classified into various subclasses like bentonite, montmorillonite, halloysite, kaolinite and hectorite. Bentonite and Montmorillonite are now enumerated as GRAS and in Effective Food Contact Substance (FCS) regulations by the U.S. FDA (Table 2 B). FCS operates as the U.S. FDA in effect premarket guidelines for food contact materials that have been established to be safe and sound for their proposed usage. Nevertheless, recent study designates probable migration risks related with nano clay packing (Muthu et al., 2018; Störmer et al., 2017). For food storage and preservation, edible covering with nanomaterials encoded has also demonstrated wonderful potential. Coated fresh foods for example fruits and vegetables remains fresh throughout storage and transportation processes.

Other usages in food contact packing comprise of toxins detection (Daniela et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2018), pesticides detection (Monalisa et al., 2021; Sahoo et al., 2018) and pathogens detection (Kearns et al., 2017). These are under active research and advancement because of the ultra-sensitive tendencies of nanomaterials. A current report from Sahoo et al. (2018) discovered that ZnO quantum dots (QD) could be applied to distinguish several pesticides comprising glyphosate, atrazine, aldrin and tetradifon because of the fact that the pesticide comprising of strong leaving groups (e.g., -Cl) act together with QD rapidly with huge binding affinity at 107 M−1. Additionally, ZnO QD could also photocatalyze pesticides during interaction. In order to utilize sensors based on nanomaterials for examining the quality of food, “smart packaging” has become immensely popular.

7 Application of nanotechnology in food safety

Safety of food is an emerging concern for public health. The important aspect regarding food safety is that it does not pose any risk or harm to the user while consuming (Pal, 2017). Recent advances in nanotechnology have transformed the food manufacturing, by its several usages in food safety, processing, and security and also increasing nutraceutical worth and shelf-life and slashing packing waste (Wesley et al., 2014). Pathogens, contaminants, and toxins are a major risk for the health of human beings. Progresses in nanotechnology have enhanced the shelf-life, detection of toxins, and microbial contamination (Inbaraj and Chen, 2016). Moreover, nanomaterials as well as quantum dots, nanotubes made of carbon and nanoparticles containing metals could be utilized to make biosensors for the detection of food pathogens (Wesley et al., 2014)

Nanoparticle application for the ascertainment of food pathogens and toxins was stated (Burris et al., 2012). By using several nanostructured materials (NSMs) and organic receptors in a unified system, nano-biosensors are created as bioanalytical tools (Chandra et al., 2011). To ascertain the pathogens, present in food and substances that spoil the food, several kinds of biosensors have been created (Li et al., 2014). In food samples, biosensors based on fluorescent dye and magnetic NPs have been created for finding Campylobacter (Stutzenberger et al., 2007), E. coli (Cheng et al., 2009), and Salmonella (Fu et al., 2008). Food pathogens like E. coli, Salmonella sp., Listeria monocytogenesin and mycotoxins present in food can be easily detected by applying specially designed biosensors (Durán and Marcato, 2013). In order to swiftly and precisely identify the microbes, surface enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is used as nano-biosensing device. To find bacteria silver nano colloids are generally applied in SERS (Baranwal et al., 2016), since silver nano colloids increase Raman signs. In addition to silver nano colloids, silver NPs (Abbaspour et al., 2015), graphene oxide (Zuo et al., 2013), plasmonic gold (Fang et al., 2017), carbon nanotubes (Yang et al., 2013), and magnetic beads (Holzinger et al., 2014) are generally applied to find pathogens present in food. Ascertainment of E. coli present in food is possible now by the detection of scattering of light by cells. This sensor works by binding to an identified protein and represented as bacteria on a chip made of silicon having a tendency to bind further with other E. coli existent on the food (Bhattacharya et al., 2007). Synthesized DNA molecular beacons are utilized as nano-barcodes to detect pathogens present in food (Li et al., 2004). Chen and Durst (2006) created an immunosorbent assay based on array to find Listeria monocytogenesin, E. coli O157:H7, and Salmonella sp., by applying G-liposomal nano-vesicles protein. DeCory et al. (2005) created a beadimmunoliposome assay to swiftly ascertain E. coli O157:H7 present in aqueous samples. Moreover, several investigators have used liposome-based techniques to detect pathogens (Shukla et al., 2016). Nano sensors like nano cantilevers use materials based on silicon to distinguish proteins and identify pathogens which vibrate at various frequencies subject to biomass (Jain, 2003). Thakur et al. (2018) found single bacterial cell of E. coli by applying a nanoparticle based diminished graphene field-influence transistor instrument. Moreover, by using magnet based nanoglodimmuno sensor, aflatoxins formed by A. parasiticus, and Aspergillus flavus that soil food could be identified (Tang et al., 2009).

8 Toxicologic fundamentals and risk evaluation

8.1 Exposure paths and their relations

The growing usage of nanomaterials in the food sector has fascinated public attentions over the past few years. Either the nanomaterials are purposefully put in as additives in food or involuntarily introduced through migration (Hannon et al., 2016) in numerous foodstuffs. Due to the exclusive physiochemical properties of nanomaterials, their applications and usage increases, subsequently raising apprehensions about the human health and ecology (He et al., 2018).

In ecology and environs, the performance and outcome of nanomaterials is mainly dependent on the physiochemical properties of the nanomaterials. Moreover, the intricacy of the conditions prevalent in the environment confines the probability of the performance and outcome of nanomaterials. Due to the intricate nano-bio-eco relations, it is hard to track and examine the allocation of nanomaterials (He et al., 2018). Though a universal methodology has been suggested for interpretation of the nano-bio-eco relations amongst the abiotic and biotic environments and nanomaterials in a linked ecosystem (He et al., 2014a), case-by-case investigations are required for a decisive evaluation of nanotoxicity in the environment.

8.2 Safety issues

In spite of the enormous advantages of NPs in food sector, there is immense concern related to their toxicity and noxious effect on environment. The prime aspects related to the behavior, fate, biological accessibility, disposal, and harmfulness of NPs to environment was described by Klaine et al, (2008). NPs are purposefully supplemented as food additives or coincidentally introduced through migration (Hannon et al., 2016) in various food products. Upfront exposure of buyers to NPs used in food sector jeopardizes the health of humans. Exposure is limited till the NPs remain in food packing. But there are high risks associated with the passage of NPs to humans by ingestion of food. Impact of NPs on health of humans and safety related to the usage of NPs was stated by Teow et al, (2011). They described the entries of NPs, their distribution and absorption in human bodies, emphasizing the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity. To have an understanding of the mode of action, behavior, and functioning of NPs in living systems, in order to develop safe nanotechnology, was described by Stark, (2011). Various previous researches have disclosed the toxic effect of NPs used in food and packaging. The toxic effect of NPs on human organs relies on their physicochemical features like biological distribution and availability, concentration in food product and quantity of food ingested (Wani and Kothari, 2018). NPs like asbestos (Hett, 2004), could activate immune response or settle down in brain (Scrinis, 2008).

Toxic assessment of Metal NPs was studied by Schrand et al. (2010), They stated that as NP size reduces, its toxic level enhances. Small NPs having high reactivity and capability to traverse membranes and capillaries could pile up in CNS (Central Nervous System) (Borm and Kreyling, 2004). Interaction of NPs with enzymes and proteins could trigger oxidative stress and production of ROS (Reactive oxygen species) inducing damage to mitochondria and cell, leading to cell death (He et al., 2014b). Overgeneration of ROS could damage neurons (Long et al., 2007), acute DNA damage (He et al., 2014b), autophagy (Khan et al., 2012) carcinogenesis, mutagenesis, and age-related illnesses in human beings. TiO2 NPs could trigger tumorlike alterations in cells of human beings (Botelho et al., 2014) and anti-caking silica NPs could be cytotoxic in lung cells (Athinarayanan et al., 2014). Silver NPs affect fibroblast in human lungs by enhancing ROS, reducing ATP level, inducing chromosomal anomalies, and damaging mitochondria and DNA. (Kim et al., 2007). Carbon Nanotubes, generally used in food packing has toxic effects on human lungs and skin (Mills and Hazafy, 2009). Jovanović (2015) stated the accumulation of TiO2 NPs in human bodies by eating chewing gums having TiO2 NPs. Similarly, Athinarayanan et al. (2014) reported the accumulation of SiO2 NPs in gut epithelia after eating food having E551. Various Metal NPs like CuO (Karlsson et al., 2013), Ag (McShan et al., 2014), and ZnO (Fukui et al., 2012) could have harmful effects in food stimulants by increasing intracellular ROS triggering peroxidation in lipids and damage to DNA (Fukui et al., 2012). Furthermore, there are less toxicological researches on NPs used in edible coatings and food packing. There are limited documented studies on prospective toxicity of NPs on human beings. Hence, risk assessment researches to identify the harmful and noxious effects of NPs on the health of human beings must be crucially investigated and in silico, in vitro, and in vivo analysis are required to standardize protocols for regulating safety issues and risk assessment related to the usage of NPs in food sector.

8.3 Data creating and its analysis

In food industry, systematic and precise evaluation of nanotoxicology is fundamental to safe use, sensible engineering, management and usage of nanomaterials. Additionally, recent procedures characteristically applied for toxicology deliver slight information that is beneficial for chemists to develop their sustainable blueprint for large scale application (Maertens and Plugge, 2018). On the basis of many research studies on cell damage both in vivo and in vitro, the toxicological figures are yet mostly restricted to extend any decisive statement regarding the regular pattern of exposure to nanomaterials and their noxious effect on the health of human beings. By means of model organisms and cell lines for example Escherichia coli (Gou et al., 2010) and cell lines of human A549 lung adenocarcinoma (Li et al., 2016), respectively, for producing omics figures is possibly the upcoming mechanism for the analysis of nanotoxicity. At the same time, machine learning methodology must be modified to study the increasing data.

9 Frontline issues

Even though various studies exhibited less noxious impact of nanomaterials in food produces (Xiaojia et al., 2019; Dudefoi et al., 2017), the noxiousness may get changed due to long-term exposure. Little is known about the biodistribution and bioavailability of nanomaterials therein and the severe and lasting toxicity upon coming in contact with them. Currently, France has decided to re-evaluate the safety of TiO2 (E171) as additives in food at the legislature level. French Agricultural Research Institute led research group in 2017, stated the pretumorous, non-malicious harms in the rat colons who were fed with TiO2 NPs for>100 days (Bettini et al., 2017). Afterwards, agency for French Food safety assessed the French Agricultural Research Institute research and made suggestions on the carcinogenic capability of TiO2 to European Chemicals Agency. In 2018, one of the amendments in French Farm and Food bill gets cleared in the National Assembly, is aimed to ban the promotion and trading in of TiO2 food additives in food industry by 2020, though it is not yet finalized (France USDA, 2018). A U.S. based company; Dunkin Donuts has also said that they will stop the usage of TiO2 NPs in their donuts. French confectionary subsidiary of Mars Inc., and Mars Chocolate, France, have by now declared to ban TiO2. Advancement made on prohibiting the application of E171 is an illustration of how law and regulations would influence the usage and promotion of nano-food. Although nanotechnology has huge benefits, the prospect of nanotechnology in food manufacturing is still undefined because of their toxicity, laws and regulations and awareness and its acceptance in public.

There is an ongoing debate on the possible hazards of conventional nanomaterials. Additional information on risk evaluation is certainly essential. Furthermore, various strategies have been applied to decrease the noxiousness of engineered nanomaterials and in the meantime, enhance the choice and preference of target and performance consistency. In order to create engineered nanomaterials less toxic and more viable, precise tailoring on doping, morphological restrain and surface function has been established as real deals.

10 Public awareness and approval

Due to their antimicrobial properties, silver nanoparticles were added into various food and milk packings. Without having any information about the adding up of these nanoparticles, common public used these products. It leads to both legislative and ethical problems. Now a days, appropriate labeling becomes obligatory so that public is conscious of what they eat. It is producer's accountability to keep this data clear and accessible to the general public. Approval and awareness amongst public are a significant issue but it is frequently overlooked by a food producer as they tend to keep their expertise secret.

11 Assessment of nanotechnology

In each and every part of food manufacturing, nanotechnology shows favorable possibilities to be used extensively. It is based on restricted information attained primarily from laboratories. Taking into account, the uncertain ecological effect and the meager ability to regulate properties and material interaction at nanoscale level, the applied usage of nanotechnology and promoting nanomaterial centered produce remains undefined. In turn, it correspondingly confines the advancement of the legislator and regulatory bodies, additionally becoming a hindrance for publicizing of innovative goods. There is low level of awareness among public regarding food nanotechnology. Public needs to be notified regarding the status of food nanotechnology whereas food producers choose the contrary because their expertise is secret. For achievement in present biotechnology industry, applying ecologically responsive practices has become most crucial. Since, food manufacturing is a trillion-dollar business, numerous goods related to nanotechnology have been promoted globally for example packing materials. It will remain a challenge for the producer because of monitoring of safety codes by government legislatives.

12 Conclusion

Innovative researches and their consequent viable applications are emerging and amplifying their extent from one domain to another. There is enormous potential in nanotechnology for improving and evolving food industry across a broad spectrum covering numerous domains of specialties as well as embodying various facets of food management. In food industry and technology, nanotechnology has a bright role in enhancing shelf life, storage, safety, security, superior quality, high nutrition value, therapeutic and fortified food free from pathogens packed in an elegant and dynamic manner. Nanotechnology enables a drastic improvement in properties of food packing material but more studies and advancement are required to figure out the potential benefits and detriments. It enhances the functionality of food packing materials by improving the food properties like tasty, nutritious, and healthy food, when packed. It is generally acknowledged that nanofoods would be widely available to consumers globally in upcoming years.

The foremost concern for researchers and monitoring bodies are benefits to end users and food safety. Therefore, it is vital to invest monetary resources, innovative researches, and ample time to attain the commercialization of nanofoods. Various legislative agencies like FDA emphasize upon nanoparticle features for example size of particles, their hazardous properties, and correlation with their absorption in human intestines. The food companies must precisely pursue the guidelines issued by legislative bodies for example WHO and FDA to assess the safety, security, packing, storage, and usage of supplements in food. Limited documented work is available regarding safety of humans after oral consumption of nanoparticles and their distribution, absorption, and metabolism. It is essential innovate novel tests for examining the noxious effects of NPs on the health of human beings and also exposure risks. Moreover, it is essential to formulate stringent monitoring guidelines regarding the safe usage of nanomaterials in food stuffs at world level. The application of computational and instrumentation science could enable scientists to have exceptional knowledge regarding toxicologic and hazardous impact of NPs on cell lines and tissues in human beings. Therefore social, scientific, and technical considerations are essential to augment the nanotechnology applications in various domains. Furthermore, it is also essential to engineer NPs with latest techniques to make them highly safe and effective in food sector.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for funding this project under grant number: 13-AGR2119-07. We also express our gratitude to King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia for providing administrative and technical support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aptamer-conjugated silver nanoparticles for electrochemical dual-aptamer-based sandwich detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2015;68:149-155.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arsenic and selenium removal from water using biosynthesized nanoscale zerovalent iron: a factorial design analysis. Process Safe Environ.. 2017;107:518-527.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alpha amylase assisted synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles: structural characterization and application as antibacterial agents. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2015;283:171-177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Self-grown one-dimensional nickel sulfo-selenide nanostructured electrocatalysts for water splitting reactions. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy.. 2020;45(32):15904-15914.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of NiOx@NPC composite for high-performance supercapacitor via waste PET plastic-derived Ni-MOF. Compos. B Eng.. 2020;183:107655

- [Google Scholar]

- Biogenic Nano-Particles and their Use in Agro-ecosystems. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2020. p. :457-488.

- [CrossRef]

- Synthesis, characterization and biocompatibility of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Nigella sativa leaf extract in comparison with chemical silver nanoparticles. Ecotox. Environ. Safe.. 2015;120:400-408.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presence of nanosilica (E551) in commercial food products: TNF-mediated oxidative stress and altered cell cycle progression in human lung fibroblast cells. Cell Bio. and Toxicol.. 2014;30(2):89-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green biosynthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using brown marine macroalga Sargassum muticum aqueous extract. Mater. Lett.. 2014;116:275-277.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiparametric magneto-fluorescent nanosensors for the ultrasensitive detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7. ACS Infect. Dis.. 2016;2:667-673.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phyto fabricated metallic nanoparticles and their clinical applications. RSC Adv.. 2016;6(107):105996-106010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by lignin-degrading fungus. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2016;3:8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Food-grade TiO2 impairs intestinal and systemic immune homeostasis, initiates preneoplastic lesions and promotes aberrant crypt development in the rat colon. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biomems and nanotechnology based approaches for rapid detection of biological entities. J. Rapid Meth. Autom. Microbiol.. 2007;15:1-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological hazards of inhaled nanoparticle-potential implications for drug delivery. J. Nanosci. Nanotech.. 2004;4(5):521-531.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in human gastric epithelial cells in vitro. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2014;68:59-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fluorescent nanoparticles: Sensing pathogens and toxins in foods and crops. Trends Food Sci. Technol.. 2012;28:143-152.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of daunomycin using phosphatidylserine and aptamer coimmobilized on Au nanoparticles deposited conducting polymer. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2011;26(11):4442-4449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles using Pichia fermentans JA2 and their antimicrobial property. Appl. Nanosci.. 2015;5(1):63-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simultaneous detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes with an array-based immunosorbent assay using universal protein G-liposomal nanovesicles. Talanta. 2006;69(1):232-238.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combining biofunctional magnetic nanoparticles and ATP bioluminescence for rapid detection of Escherichia coli. Talanta. 2009;77(4):1332-1336.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to responsible innovation of nanotechnology applications in food and agriculture: A study of US experts and developers. NanoImpact.. 2021;23:100326.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Electronic code of federal regulations. Title 21: Food and drugs. part 73 d listing of color additives exempt from certification. The United States office of the federal register (OFR) and the United States. Government Publishing Office; 2018. https:// www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text.

- Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Electronic code of federal regulations. title 21: food and drugs. part 184d direct food substances affirmed as generally recognized as safe. subpart b dlisting of specific substances affirmed as gras. the united states office of the federal register (ofr) and the united states. Government Publishing Office; 2018. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID¼79a76b1d7e7a98ae9.

- Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Title 21–food and drugs. Chapter i–food and drug administration. Department of health and human services. Subchapter B–food for human consumption (continued). Part 172 – food additives permitted for direct addition to food for human consumption. Subpart E–anticakingagents. Sec. 172.480 silicon dioxide. United State Food and Drug Administration; 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/.

- Nanotechnologies in the food industry recent developments, risks and regulation. Trends Food Sci. Technol.. 2012;24(1):30-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances and challenges on applications of nanotechnology in food packaging: A literature review. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2019;134:110814.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An Introduction to food grade nanoemulsions: Nanotechnology in food sector. Springer Singapore 2018:1-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of an immunomagnetic bead immunoliposome fluorescence assay for rapid detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in aqueous samples and comparison of the assay with a standard microbiological method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2005;71(4):1856-1864.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Coffea arabica seed extract and its antibacterial activity. Mater Sci. Eng.. 2016;58:36-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Continuous in vitro exposure of intestinal epithelial cells to E171 food additive causes oxidative stress, inducing oxidation of DNA bases but no endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nanotoxicology 2017:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of food grade and nano-TiO2 particles on a human intestinal community. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2017;106:242-249.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanobiotechnology perspectives. Role of nanotechnology in the food industry a review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2013;48(6):1127-1134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanomaterials for food packaging applications: A systematic review. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2020;46:111825

- [Google Scholar]

- Yeast-derived biosynthesis of silver/silver chloride nanoparticles and their antiproliferative activity against bacteria. RSC Adv.. 2016;6(12):9893-9904.

- [Google Scholar]

- Euroapen Commision. Regulation (EC) No. 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Food Additives. The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union; 2008. https://eur-lex. europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri¼celex% 3A32008R1333.

- Active and intelligent packaging in meat industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol.. 2017;61:60-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracellular biosynthesis of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles by Bacillus cereus strain HMH1: characterization and in vitro cytotoxicity analysis on MCF-7 and 3T3 cell lines. J. Biotechnol.. 2018;270:1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of silver nanoparticles using yeasts and evaluation of their antifungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi. Process Biochem.. 2016;51(9):1306-1313.

- [Google Scholar]

- France USDA, 2018. Plans to ban titanium dioxide in food products. Information Network (GAIN) Report. Global Agriculture: USDA Foreign Agriculture Service. https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/france-france-plans-ban-titanium-dioxide-food-products. Accessed 11 Jan 2020Accessed 11 Jan 2020

- An Au/Si hetero-nanorod based biosensor for Salmonella detection. Nanotechnology.. 2008;19:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of zinc ion release and oxidative stress induced by intratracheal instillation of ZnO nanoparticles to rat lung. Chemico-Biol. Intera.. 2012;198(3):29-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Edible bio-nano-hybrid coatings for food protection based on pectins and LDH-salicylate: preparation and analysis of physical properties. LWT-Food Sci. Technol.. 2016;69:139-145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanistic toxicity assessment of nanomaterials by whole-cell-array stress genes expression analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2010;44(15):5964-5970.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasoundassisted biosynthesis of CuO-NPs using brown alga Cystoseira trinodis: characterization, photocatalytic AOP, DPPH scavenging and antibacterial investigations. Ultrason. Sonochem.. 2018;41:109-119.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the migration potential of nanosilver from nanoparticle-coated lowdensity polyethylene food packaging into food simulants. Food Addit. Contam. A.. 2016;33:167-178.

- [Google Scholar]

- An in vivo study on the photo enhanced toxicities of S-doped TiO2 nanoparticles to zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio) in terms of malformation, mortality, rheotaxis dysfunction, and DNA damage. Nanotoxicology.. 2014;8:185-195.

- [Google Scholar]

- Using a holistic approach to assess the impact of engineered nanomaterials inducing toxicity in aquatic systems. J. Food Drug Anal.. 2014;22:128-146.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity of engineered nanomaterials mediated by nano-bio-eco interactions. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev.. 2018;36(1):21-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hett, A., 2004. Nanotechnology: Small Matter, Many Unknowns. Swiss Reinsurance, Zurich, pp. 1–55.

- Green preparation and spectroscopic characterization of plasmonic silver nanoparticles using fruits as reducing agents. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol.. 2015;6:293-299.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanomaterial-based sensors for detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens and toxins as well as pork adulteration in meat products. J. Food Drug Anal.. 2016;24:15-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanodiagnostics: application of nanotechnology in molecular diagnostics. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn.. 2003;3(2):153-161.

- [Google Scholar]

- Critical review of public health regulations of titanium dioxide, a human food additive. Inte. Environ. Ass. Manage.. 2015;11(1):10-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cell membrane damage and protein interaction induced by copper containing nanoparticles- Importance of themetal release process. Toxicology. 2013;313(1):59-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- SERS detection of multiple antimicrobial-resistant pathogens using nanosensors. Anal. Chem.. 2017;89(23):12666-12673.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enzymatic browning reduction in white cabbage, potent antibacterial and antioxidant activities of biogenic silver nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq.. 2016;215:39-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Induction of ROS, mitochondrial damage andautophagy in lung epithelial cancer cells by iron oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33(5):1477-1488.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med.. 2007;3(1):95-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanomaterials in the environment: behavior, fate, bioavailability, and effects. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.. 2008;27(9):1825-1851.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology and its challenges in the food sector: a review. Mater. Today Chem.. 2020;17:100332.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Integrative functional transcriptomic analyses implicate specific molecular pathways in pulmonary toxicity from exposure to aluminum oxide nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology. 2016;10(7):957-969.

- [Google Scholar]

- Raman spectroscopy in the analysis of food and pharmaceutical nanomaterials. J. Food Drug Anal.. 2014;22(1):28-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanosize titanium dioxide stimulates reactive oxygen species in brain microglia and damages neurons in vitro. Environ. Health Perspect.. 2007;115:1631.

- [Google Scholar]

- Better metrics for “sustainable by design”: toward an in silico green toxicology for green(er) chemistry. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng.. 2018;6(2):1999-2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- (Bio) Nanotechnology in Food Science—Food Packaging. Nanomaterials.. 2021;11(2):292.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular toxicity mechanism of nanosilver. J. Food and Drug Anal.. 2014;22(1):116-127.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanocrystalline SnO2-based, UVB-activated, colourimetric oxygen indicator. Sens. Actuators, B. 2009;136(2):344-349.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S., Singh, B.R., Singh, A., Keswani, C., Naqvi, A.H., Singh, H.B., 2014. Biofabricated silver nanoparticles act as a strong fungicide against Bipolaris sorokiniana causing spot blotch disease in wheat. PLoS One 9, 97881.

- Nanotechnology: Current applications and future scope in food. Food Frontiers.. 2021;2(1):3-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology: current uses and future applications in the food industry. 3. Biotech.. 2018;8:74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis characterization and antibacterial activity of copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) from actinomycetes. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol.. 2018;15:56-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology: a new approach in food packaging. J. Food Micro. Safety Hy.. 2017;2:121.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis, characterization of gold and silver nanoparticles and their potential application for cancer therapeutics. Mater. Sci. Eng., C. 2015;53:298-309.

- [Google Scholar]

- Butea monosperma bark extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: characterization and biomedical applications. J. Saudi Chem. Soc.. 2017;21(6):673-684.

- [Google Scholar]

- TiO2 nanoparticle biosynthesis and its physiological effect on mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) Biotechnol. Rep,. 2015;5:22-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Atrocarpus altilis leaf extract and the study of their antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Mater. Lett.. 2016;180:264-267.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of antimicrobial edible coating of thymol nanoemulsion/ quinoa protein/chitosan on the safety, sensorial properties, and quality of refrigerated strawberries (Fragaria ananassa) under commercial storage environment. Food Bioprocess Technol.. 2018;11(8):1566-1574.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology research directions for societal needs in 2020: Retrospective and outlook. Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York: Springer; 2011.

- Photocatalytic activity of biogenic silver nanoparticles synthesized using yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) extract. Appl. Nanosci.. 2015;5(8):953-959.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanosensing of pesticides by zinc oxide quantum dot: an optical and electrochemical approach for the detection of pesticides in water. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2018;66(2):414-423.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of antimicrobial nanoemulsions as edible coatings: impact on safety and quality attributes of Fuji apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol.. 2015;105:8-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Cassia tora leaf extract and its antioxidant and antibacterial activities. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2015;28:277-281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrinis, G., 2008. On the ideology of nutritionism. Gastronomica. 8 (1), 39–48.

- Metal-based nanoparticles and their toxicity assessment. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. Nanoparticl. Toxicity.. 2010;2(5):544-568.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of on the physicochemical characteristics of longan fruit under ambient temperature. J. Food Eng.. 2013;118:125-131.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnologies in Food Science: Applications, Recent Trends, and Future Perspectives. Nano-Micro. Lett.. 2020;12:45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunoliposomebased immunomagnetic concentration and separation assay for rapid detection of Cronobacter sakazakii. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2016;77:986-994.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology application in food packaging: a plethora of opportunities versus pending risks assessment and public concerns. Food Res. Inter.. 2020;137:109664

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology applications in functional foods; opportunities and challenges. Prevent. Nutri. Food Sci.. 2016;21(1):1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological synthesis of nanoparticles from plants and microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol.. 2016;34(7):588-599.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biogenic silver and gold nanoparticles synthesized using red ginseng root extract, and their applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol.. 2016;44:811-816.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver and gold nanoparticles synthesized from Streptomyces sp. isolated from with special reference to its antibacterial activity against pathogens. J. Cluster Sci.. 2017;28:59-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoparticles in biological systems. Angewandte Chemie Int. Edn.. 2011;50(6):1242-1258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Critical review of the migration potential of nanoparticles in food contact plastics. Trends Food Sci. Technol.. 2017;63:39-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stutzenberger, F.J., Latour, R.A., Sun, Y., Tzeng, T. 2007. Adhesin-specific nanoparticles and process for using same. US Patent No 20070184120.

- Pathogenic detection and phenotype using magnetic nanoparticle-urease nanosensor. Sens. Actuators, B. 2018;259:428-432.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic nanogold microspheresbased lateral-flow immunodipstick for rapid detection of aflatoxin B2 in food. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2009;25:514-518.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health impact and safety of engineered nanomaterials. Chem. Commun.. 2011;47(25):7025.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid detection of single E. coli bacteria using a graphene-based field-effect transistor device. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2018;110:16-22.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 10/2011 of 14 January 2011 on plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food Text with EEA relevance. Official J. Eur. Union.. 2011;12:1-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Waste PET plastic derived ZnO@NMC nanocomposite via MOF-5 construction for hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. J. King Saud Uni – Sci.. 2020;32(4):2397-2405.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrothermal synthesis of novel nickel oxide@nitrogenous mesoporous carbon nanocomposite using costless smoked cigarette filter for high performance supercapacitor. Mater. Lett.. 2020;266:127492

- [Google Scholar]

- US DOA 2003. Nanoscale science and engineering for agriculture and food systems: a report submitted to cooperative state research, education and extension service. Washington, DC: Department of Agriculture; 2003. the United States.

- US FDA 2018. Inventory of effective food contact substance (FCS) notifications. Administration USFaD. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/?set¼FCN. Accessed 11 Jan 2020.

- US FDA, 2018. Food additive status list. US FDA/CFSAN Office of Food Additive Safety. https://www.fda. gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/ FoodAdditivesIngredients/ucm091048.htm. Accessed 11 Jan 2020

- Prospects of using nanotechnology for food preservation, safety, and security. J. Food Drug Anal.. 2018;26(4):1201-1214.

- [Google Scholar]

- Agricultural nanotechnology: applications and challenges. Annals of Plant Sci.. 2018;7(3):2146-2148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review on nanotechnology applications in food packaging and safety. Int. J. Eng. Res.. 2014;3(11):645-651.

- [Google Scholar]

- The current application of nanotechnology in food and agriculture. J. Food Drug Anal.. 2019;27(1):1-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly specific and cost-efficient detection of Salmonella paratyphi combining aptamers with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Sensors.. 2013;13:6865-6881.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanobiotechnology applications in food sector and future innovations. Microb. Biotech. in Food and Health. 2021:197-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quintanar-Guerrero D. The effect of nano-coatings with A-tocopherol and xanthan gum on shelf-life and browning index of fresh-cut “red delicious” apples. Innovat. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol.. 2014;22:188-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasmon coupling enhanced Raman scattering nanobeacon for single-step, ultrasensitive detection of cholera toxin. Anal. Chem.. 2016;88(15):7447-7452.

- [Google Scholar]

- A PDMS/paper/glass hybrid microfluidic biochip integrated with aptamer functionalized graphene oxide nano-biosensors for one step multiplexed pathogen detection. Lab Chip. 2013;13(19):3921.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101530.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: