In vivo and in vitro anticoccidial efficacy of Astragalus membranaceus against Eimeria papillata infection

⁎Corresponding author. azema1@yahoo.com (A.S. Abdel-Baki)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Coccidiosis is a parasitic disease of wild and domestic animals caused by Eimeria spp. Currently, several drugs are available for the control of this disease but resistance has been confirmed for all them. There is an urgent need, therefore, for the identification of new compounds as alternative treatments to control coccidiosis. Astragalus membranaceus proven to have anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, immunomodulating and anticancer activities. The present study was therefore undertaken to assess the in vivo and the in vitro anticoccidial activity of Astragalus membranaceus root (AMR). Mice were divided into five groups, with the first left non-infected and the second, third, fourth and fifth groups being infected with 1 × 103 sporulated oocysts of E. papillata. The third, fourth and fifth groups also received, respectively, an oral dose of 10, 25 and 50 mg/kg AMR suspended in physiological saline daily for five consecutive days. 50 mg/kg, was the most effective dose, inducing a significant reduction in the number of oocysts output in mice faeces (by about 57%), accompanied by a significant decrease in the number of parasitic stages in jejunal sections. Moreover, the treatment with AMR increased the number of goblet cells and upregulated the expression of its specific gene, MUC2. In addition, our study proved that AMR reduced oxidative damage since levels of TBARS decreased (indicating reduced lipid peroxidation), levels of glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) increased, and the mRNA level of iNOS was downregulated. Also, AMR treatment revealed anti-apoptotic activity as it was able to regulate the gene expression of Bcl-2 in the jejunum of E. papillata infected mice. Finally, the in vitro study revealed that AMR significantly inhabited the oocyst sporulation in a dose dependent manner. Overall, therefore, our results indicate that AMR exhibits significant in vivo and in vitro anticoccidial effects.

Keywords

Coccidia

Astragalus membranaceus

Oxidative stress

MUC2

iNOs

Bcl2 sporulation

1 Introduction

Eimeria are the most significant protozoan parasites of Phylum Apicomplexa. They are considering the main risk to avian production since they are the causative agent of avian coccidiosis (Blake et al., 2015). The life cycle of the Eimeria involves two phases; an exogenous phase in the environment and an endogenous phase in the intestine of animals (Lal et al., 2010). Eimeria infect the digestive tract of their hosts and immediately reproduce in their cells (Mehlhorn, 2014). This causes malabsorption of nutrients, diarrhoea, with or without blood, high feed conversion, weight loss, increased susceptibility to bacterial pathogens and, in severe cases, even death (Alnassan et al., 2014). Of the various Eimeria species Eimeria papillata infects the mouse jejunum, causing extensive damage to the intestinal mucosa, inflammation and oxidative stress (Abdel-Latif et al., 2016). It therefore represents an appropriate model to study animal coccidiosis (Dkhil, 2013).

Astragalus membranaceus, also known as Huang-qi, is a therapeutic herb utilised in numerous herbal formulations to treat a wide variety of diseases and body disorders (Auyeung et al., 2016). Many reports have portrayed the potential remedial values of AMR, including anti-virus, anti-stress, anti-aging, anti-radiation, anti-microbial and anti-cancer properties (Qiao et al., 2018). These have been associated with its immunomodulating, anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activities of AMR (Auyeung et al., 2016). The dried roots of Astragalus membranaceus (AMR) contain numerous bioactive compounds such as polysaccharides, astragalosides, flavonoids, saponins, trace elements and amino acids (Zhao et al., 2012), and it is believed that these underpin the plant’s multifunctional biological and pharmaceutical properties. In addition, the root is additionally widely utilised as a health food supplement around the world and in poultry industry (Abla et al., 2019).

Regarding its anticoccidial properties, there is only one preliminary study on the effect of polysaccharide extracted from Astragalus membranaceus in conjunction with vaccine on the cellular and humoural immunity of E. tenella infected chickens (Guo et al., 2004).

The objective of the present study was therefore to investigate the anticoccidial effect of Astragalus membranaceus on Eimeria papillata-infected mice.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Astragalus membranaceus root

The dried powder of Astragalus membranaceus root, was purchased from Xi'an Frankherb Biotech Co., Ltd. Shaanxi, China. The root powder was suspended in physiological saline for medication at different concentrations.

2.2 Mice

Male swiss albino mice weighing 22–25 g and aged 6–7 weeks were used in the present study. The animals were kept in specific pathogen-free conditions at a controlled temperature (21 °C) with 12 h of light and 12 h of dark, free access to water and a standard mouse chow diet.

3 Parasite

The parasite used in the study was a laboratory strain of E. papillata maintained by periodic passage through coccidian-free mice. Unsporulated oocysts were obtained from the faeces of mice four days after infection and allowed to sporulate in readiness for utilisation in the experiment. The number of these newly acquired oocysts was adjusted such that each mouse was given 1 × 103 sporulated oocysts in 100 μl of physiological saline by oral gavage.

3.1 Treatment schedule

Mice were divided into five groups with eight mice in each. The first group was left uninfected and the remaining four groups were infected with E. papillata. Of these, one hour after infection, the third, fourth and fifth groups were treated with AMR at doses of 10, 25 and 50 mg/kg respectively; this AMR treatment was then repeated daily for a further four days. Faeces were collected daily and oocysts per gram (OPG) faeces were estimated using the McMaster modified technique (Schito et al., 1996). On day 5 p.i., mice were euthanised and jejuna were collected for the subsequent studies.

3.2 Intestinal tissue preparations for biochemical and histological studies

Pieces of the freshly expelled jejunum were homogenised as described by Tsakiris et al. (2004). The obtained homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 500g in a cooling centrifuge. The supernatant was isolated for use in biochemical investigations. Other different pieces of jejunum were quickly fixed in 10% formalin buffered phosphate. This fixed tissue was then processed, sectioned and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in order to assess the parasitic developmental stages in at least ten well-orientated villous

3.3 Determination of oxidative stress markers

The activity of reduced glutathione (GSH) was estimated following the method described by Ellman (1959) with slight modifications, as previously reported by Sedlak and Lindsay (1968). This method is based on the reduction of 5,5′ dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) with glutathione (GSH) to produce a yellow compound, and its values were expressed as mg /g. Also, peroxidase activity (GPX) (U/L) was quantified by spectrophotometry according to the method suggested by Kar and Mishra (1976). The lipid peroxidation activity was assayed according to the method described by Ohkawa et al. (1979). This method measures the concentration of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS).

3.4 Histochemistry

The prepared paraffin sections were deparaffinised with xylene then rehydrated gradually in descending ethanol and finally with water. Sections were then stained with Alcian blue (Sigma) to estimate the goblet cells (Allen et al., 1986). The number of goblet cells in the jejunum were counted for each animal in at least ten well-orientated villous crypt units (VCUs). Results were given as the mean number of goblet cells per ten villi.

3.5 Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from pieces of the jejunum using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Contaminating genomic DNA was digested with the DNA-free™ kit (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany), before cDNA was synthesised using a Reverse Transcription kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, California, USA). RT-PCR was performed in a TaqMan7500 (Applied Biosystems) using the QuantiTect™ SYBR® Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The specific primers for mucin 2 (MUC2), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOs), Bcl2 and 18S rRNA were obtained from Qiagen. The initial incubation was done at 50 °C for 2 min, followed by Taq polymerase activation at 95 °C for 10 min, 1 cycle, followed by 30 cycles at 95 °C for 10 min, 60 °C for 35 s and 72 °C for 30 s. All PCR reactions produced just a single yield of the expected size, as recognised by melting point analysis and gel electrophoresis. Quantitative assessment was performed with TaqMan7500 system software (Applied Biosystems). Expression of genes was normalised to that of 18S rRNA (Delic et al., 2010).

3.6 Effect of AMR on oocyst sporulation in vitro

An in vitro assay was carried out to estimate the effect of different concentrations of AMR on the sporulation of E. papillata oocysts. In this assay, we tested three concentrations (10, 25 and 50 mg)/ 5 ml potassium dichromate containing 1 × 104 oocysts. Control untreated oocysts remained without treatment and each test was performed in triplicate. All petri dishes used for these treatments were incubated for between 48 h and 96 h at 25–29 °C and 80% relative humidity. At the end of the incubation, the oocysts were washed in distilled water as described by Fatemi et al. (2015). The samples were then stored at 4 °C. The sporulation time and the number of sporulated oocysts were recorded and counted with a haemocytometer as done by Molan et al. (2009).

3.7 Statistical analysis

For the data analysis, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS (version 20) statistical program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Analysis of differences between the means of infected and non-infected controls or infected and infected+AMR was performed using Dunnett’s t-test

4 Results

4.1 Effect of AMR suspension on faecal oocyst output

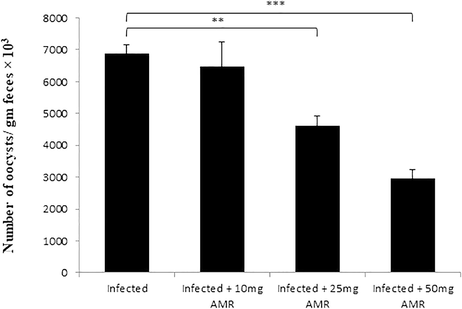

On day 5p.i. faecal oocyst output was at its peak of approximately 6875 ± 270.03 oocysts/g faeces in the infected group. The oocyst output was significantly reduced in the groups treated with AMR suspension by 5.8, 32.9 and 57%, respectively (Fig. 1). It was thus quite evident that the 50 mg/kg dose was the most effective at suppressing the faecal oocyst output. We therefore used only the 50 mg/kg dose for the subsequent investigations.

- Oocyst output profiles of mice infected with E. papillata and treated with various doses of AMR on day 5 p.i. (All values presented as Mean ± SE). * Significant difference as compared to control (P < 0.05).

4.2 Histological observations

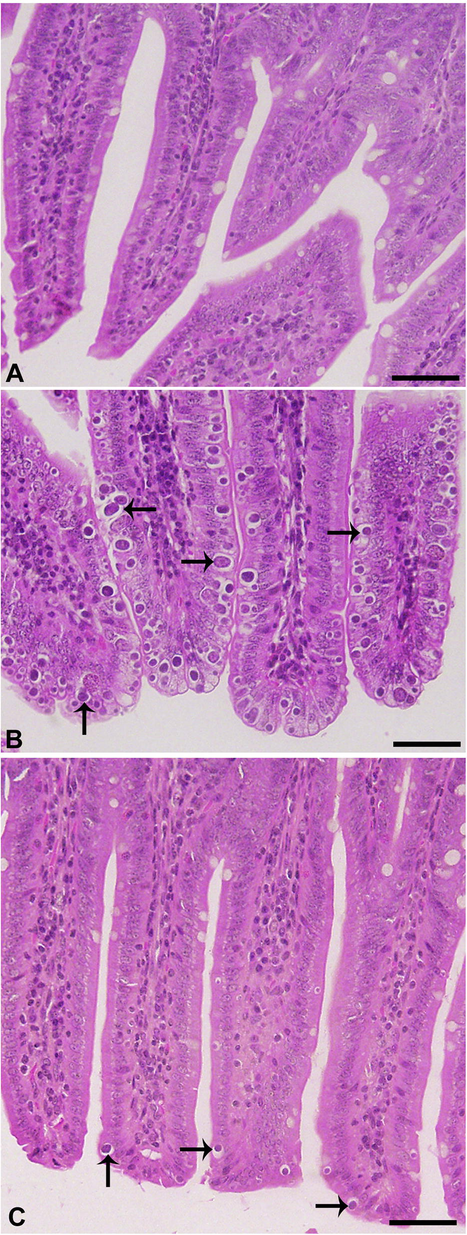

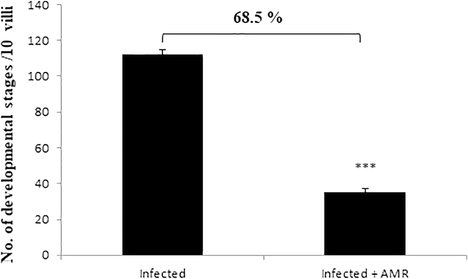

Experimental infection of mice with E. papillata oocysts led to the development of different parasite stages in the epithelial cells of the jejunum (Fig. 2). The treatment with 50 mg/kg AMR significantly reduced the number of parasitic stages per ten villous-crypt units (P < 0.001) by 68.5% in comparison to the infected group (Figs. 2, 3).

- Effect of AMR on E. papillata developmental stages in jejuna histological sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A, uninfected control; B, infected containing developmental stages (arrows); C, Infected treated with reduced numbers of developmental stages. Scale-bar = 50 µm.

- Effect of AMR induced reduction in the number of parasitic stages in mouse jejunum infected with E. papillata. (All values presented as Mean ± SE). * Significant difference as compared to control (P < 0.05).

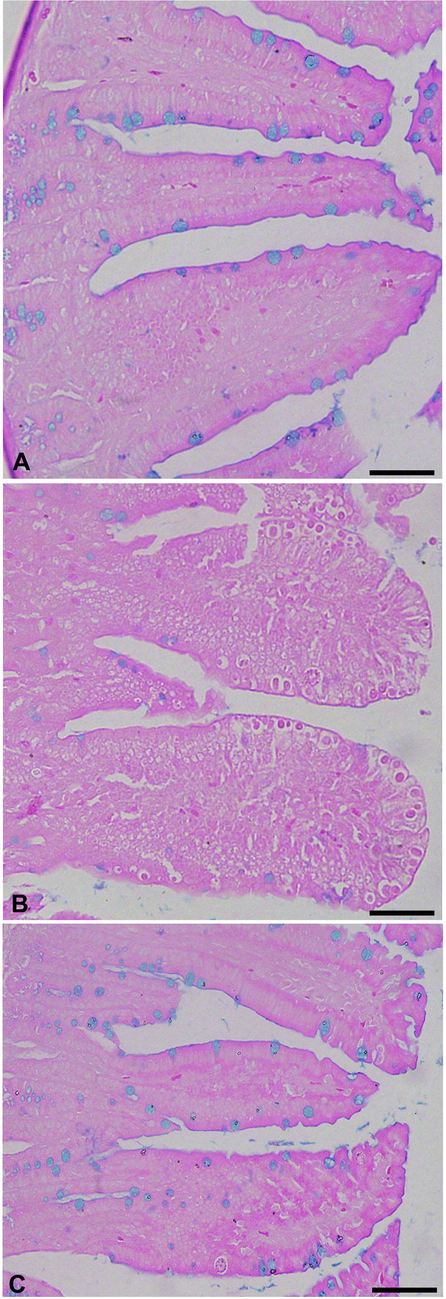

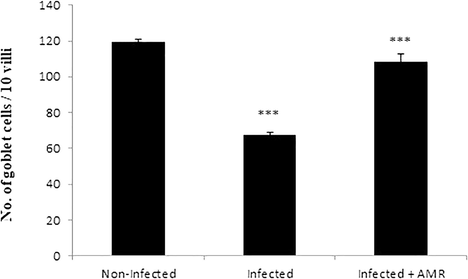

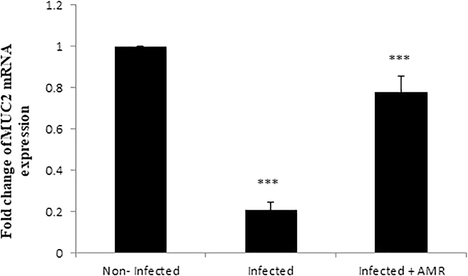

4.3 Effect of AMR on intestinal goblet cells and mRNA expression of MUC2

Microscopic examination of jejuna Alcian blue stained sections revealed that the E. papillata infection induced a significant reduction (P < 0.001) in the number of goblet cells in comparison to the non-infected group (Figs. 4, 5). The jejuna of mice treated with AMR, however, exhibited significantly higher numbers of goblet cells in comparison to the infected group (Figs. 4, 5). Similarly, a significant decrease (P < 0.001) in mRNA expression of MUC2 was observed in the infected group, but this returned close to normal (i.e. uninfected) levels in the treated group (Fig. 6).

- Effect of AMR on the number of goblet cells in mouse jejunum infected with E. papillata. A, uninfected control; B, infected containing developmental stages; C, Infected treated with reduced numbers of goblet cells. Section stained with Alcian blue. Scale-bar = 50 µm.

- Effect of AMR induced reduction in the number of goblet cells in mouse jejunum infected with E. papillata. (All values presented as Mean ± SE). * Significant difference as compared to control (P < 0.05).

- Effect of AMR on MUC2 gene expression in the jejunum of mice infected with E. papillata. Expression of gene was normalised to that of 18S rRNA, and relative expression is given as fold change compared to the non-infected control mice. Values are given as means ± SE. Significant change at P < 0.001 relative to infected mice.

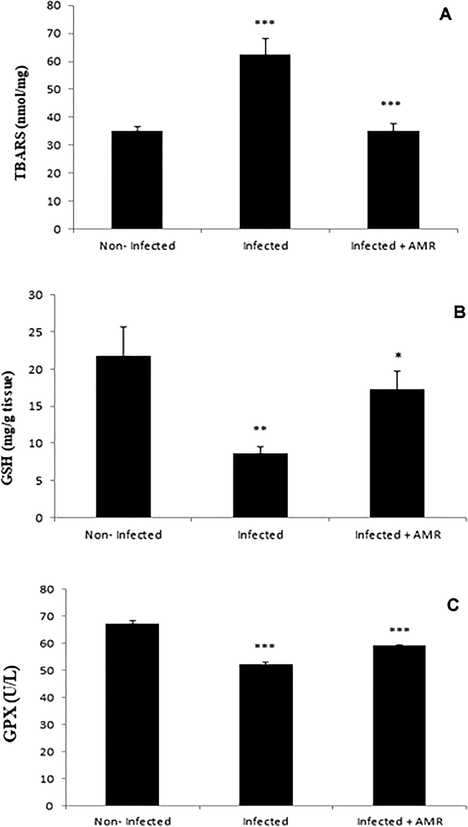

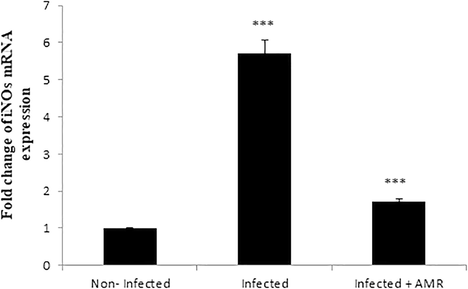

4.4 Effect of AST on oxidative stress in intestines

Compared to the non-infected group, infection with E. papillata induced a highly significant increase (p < 0.001) in TBARS and a significant decrease (P < 0.01, P < 0.001) in GSH and GPX in the infected control group (Fig. 7A–C respectively). Treatment with a dose of 50 mg/kg of AMR, however, induced a significant decrease (P < 0.001) in TBARS and significant increases in GSH and GPX (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, respectively) (Figs. 7A, 7B, 7C respectively). Additionally, the mRNA level of iNOS was upregulated due to the infection, while AMR significantly downregulated the expression of this gene (Fig. 8).

- Effect of AMR on the levels of oxidative stress parameters in mouse jejunum infected with E. papillata. A – TBARS, B – GSH and C – GPX. (All values presented as Mean ± SE). * Significant difference as compared to control (P < 0.05).

- Effect of AMR on the mRNA level of iNOS in the jejunum of mice infected with E. papillata. Expression of gene was normalised to that of 18S rRNA, and relative expression is given as fold change compared to the non-infected control mice. Values are given as means ± SE. Significant change at P < 0.001 relative to infected mice.

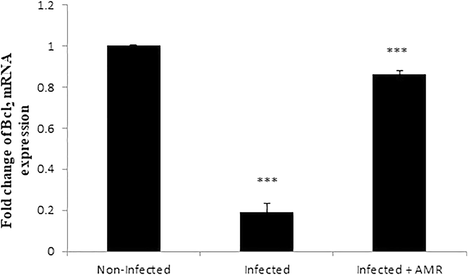

4.5 Effect of AMR on mRNA expression of Bcl2

Our results further investigated the role of AMR in infection-induced apoptosis, by evaluating the mRNA expression of Bcl-2. It was found that this was significantly (p < 0.001) downregulated after E. papillata infection but significantly increased again upon treatment with AMR (Fig. 9)

- Effect of AMR on the mRNA level of Bcl-2 in the jejunum of mice infected with E. papillata. Expression of gene was normalised to that of 18S rRNA, and relative expression is given as fold change compared to the non-infected control mice. Values are given as means ± SE. Significant change at P < 0.001 relative to infected mice.

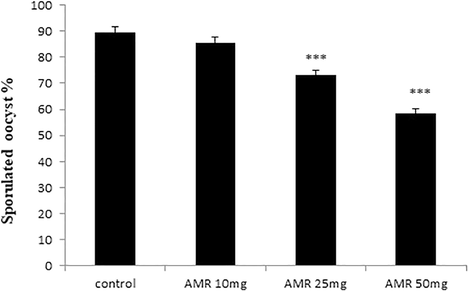

4.6 Effect of AMR on oocyst sporulation in vitro

The in vitro study revealed that 89.6% of the oocysts were sporulated in the control group while the sporulation rates in the treated groups were 85.4, 73.3 and 58.3% for 10, 25 and 50 mg/ 5 ml concentrations, respectively (Fig. 10). In other words, sporulation was 34.9 and 18.1% less than with the control group with AMR doses of 50 and 25 mg/ 5 ml, respectively. The difference in sporulation rates at the 10 mg/5 ml dose was not significant, however.

- In vitro effect of AMR on E. papillata oocyst sporulation. Dose of 10 mg have no significant effect while the other doses showed significant effect. Values are given as means ± SE.

5 Discussion

Many publications have shown that AMR has promising efficacy against a wide variety of diseases and body disorders (see Auyeung et al., 2016). According to subchronic toxicity studies of Yu et al. (2007) on AMR extract, the dose of 50 mg/kg is safe without any distinct toxicity and side effects. As well as it found that a dose of 50 mg/kg of Astragalus root extract can ameliorate the immunity of mice treated with cyclophosphamide and exhibits considerable activity against cholinesterase and oxidative stress of in a retrograde amnesia mice model (Qiu and Cheng, 2019; Abdelaziz et al., 2019 respectively). In the present study, three doses of AMR (10, 25 and 50 mg/kg) were screened as a target natural product against coccidia. In terms of anticoccidial efficacy, this study clearly demonstrated that of the all tested doses, 50 mg/kg was the most effective.

In this work, we illustrated that AMR interfered with the life cycle of E. papillata at all stages and also with oocyst sporulation, evidenced by a significant reduction in both of the developmental stages in mice jejuna and the faecal oocyst excretion, in addition to significant suppression in the rates of oocyst sporulation in a dose dependent manner. Guo et al. (2004) showed that the polysaccharide extract from AMR possesses anticoccidial activity in chicken coccidiosis, through elevation of Eimeria parasite-specific IgA that can bind and damage sporozoites, impairing their extracellular differentiation and thereby preventing parasite invasion and intracellular development. This is similar to how Bidens pilosa acts against coccidiosis in chickens by interfering with oocyst sporulation and sporozoite invasion into cells (Yang et al., 2019). It also appears that AMR suspension inhibits oocyst sporulation and this will eventually curtail infection transmission, as suggested by Fatemi et al. (2015) and Yang et al. (2019).

Goblet cells are known to act as a dynamic protective agent against pathogenic bacteria, viruses and parasites by changing the constituents of mucus and by increasing their number and size (Khan, 2008). Cheng (1974) documented that the stem cells that produce goblet cells are confined to the intestinal crypts. It is striking, therefore, that examination of jejunum histological sections revealed that the parasitic stages of E. papillata were mostly found in the crypt region, similar to the findings of Thagfan et al. (2017). It seems that, during the course of infection, these stem cells are parasitised and became unable to produce goblet cells, which could explain the significant reduction in their numbers in the infected group (Linh et al., 2009; Dkhil, 2013). This reduction was also associated with downregulation of the MUC2 gene which is widely expressed in goblet cells of the small intestine (Forder et al., 2012). This gene is responsible for regulation of mucin secretion and immune/inflammatory response against pathogen-induced injury (Forder et al., 2012; Thagfan et al., 2017). In this study, we have shown that AMR treatment interferes with the parasite development and consequently increases both the number of goblet cells and the expression of their specific gene, MUC2, to close to normal levels, as previously reported by Dkhil (2013) and Thagfan et al. (2017) while using plant extracts as anticoccidial agents against E. papillata infection.

E. papillata infection is also associated with oxidative damage within infected mucosal tissue (Abdel-Latif et al., 2016). In the present study, infection induced oxidative stress by increasing TBARS, reducing GPX and GSH levels and upregulating the mRNA level of iNOS. Similarly, Dkhil et al. (2011) found that the treatment with garlic extract increased mRNA levels of iNOS and IFN-γ, and IL-6 in E. papillata infection. Administration of AMR suspension reduced the levels of oxidative enzymes and enhanced the antioxidant capability of mice jejunum tissue through normalising the values of GSH, GPX, TBARS and iNOs. This is in line with previous research that has ascribed the pronounced potential effects of AMR to the antioxidant (El-Shafei et al., 2013) and anti-inflammatory (Auyeung et al., 2016) activities of the biologically active ingredients of this root.

Eimeria spp. have the ability to protect infected host cells from apoptosis by promoting the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 during the process of the maturation of schizonts at the initial stage of the infection (Del Cacho et al., 2004) while, at late stages of Eimeria infection, Bcl-2 expression was significantly reduced to enable the escape of the merozoites (Jiao et al., 2018). The present study revealed that on day 5 p.i., E. papillata infection suppressed the expression of Bcl-2. Similarly, Jiao et al. (2018) noticed that the expression of Bcl-2 protein in E. tenella parasitised tissue was significantly reduced on day 5 p.i. Also, Metwaly et al. (2014) found a significant increase in the total number of apoptotic cells in mice jejuna infected with E. papillata on day 5 p.i. In our study, we have shown that oral treatment with AMR suspension remarkably increased the mRNA expression of Bcl-2 on day 5 p.i., an outcome similar to that reported by Jiao et al. (2018) when using Artemisia annua extract as an anticoccidial agent, and a potential explanation for the reduced oocyst output that we noted on day 5 p.i.

In light of the above results, it can be concluded that AMR possesses notable anticoccidial activity, evidenced by the combination of reduced oocyst output and sporulation, reduced numbers of the parasite developmental stages in the jejunum, restoration of normal numbers of goblet cells and associated upregulation in the expression of the MUC2 gene. In addition, AMR acts as an antioxidant and an anti-apoptotic agent through normalising the values of GSH, GPX, TBARS and regulating the mRNA expressions of iNOs and Bcl-2 genes, which also interferes with the parasitic life cycle.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Researcher Supporting Project (RSP-2019/3), King Saud University.

References

- Protective effects of Astragalus kahiricus root extract on ethanol-induced retrograde memory impairments in mice. J. Herbmed. Pharmacol.. 2019;8:295-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticoccidial activities of chitosan on Eimeria papillata-infected mice. Parasitol. Res.. 2016;115:2845-2852.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of miRNAs and their response to cold stress in Astragalus Membranaceus. Biomolecules. 2019;9:182.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of mucus in the protection of the gastroduodenal mucosa. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl.. 1986;217:1-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Necrotic enteritis in chickens: development of a straightforward disease model system. Vet. Rec.. 2014;174:555.

- [Google Scholar]

- Astragalus membranaceus: a review of its protection against inflammation and gastrointestinal cancers. Am. J. Chin. Med.. 2016;44:1-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population, genetic, and antigenic diversity of the apicomplexan Eimeria tenella and their relevance to vaccine development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2015;112:E5343-E534350.

- [Google Scholar]

- Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. II. Mucous cells. Am. J. Anat.. 1974;141:481-501.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression of anti-apoptotic factors in cells parasitized by second-generation schizonts of Eimeria tenella and Eimeria necatrix. Vet. Parasitol.. 2004;125:287-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Testosterone-induced permanent changes of hepatic gene expression in female mice sustained during Plasmodium chabaudi malaria infection. J. Mol. Endocrinol.. 2010;45:379-390.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-coccidial, anthelmintic and antioxidant activities of pomegranate (Punica granatum) peel extract. Parasitol. Res.. 2013;112:2639-2646.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticoccidial and antiinflammatory activity of garlic in murine Eimeria papillata infections. Vet. Parasitol.. 2011;175:66-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of different levels of astragalus root powder in broiler chick diets on the physiological and biochemical changes. J. Appl. Sci. Res.. 2013;9:2104-2118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Artemisia annua extracts on sporulation of Eimeria oocysts. Parasitol. Res.. 2015;114:1207-1211.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative analyses of genes associated with mucin synthesis of broiler chickens with induced necrotic enteritis. Poult. Sci.. 2012;91:1335-1341.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of mushroom and herb polysaccharides on cellular and humoral immune responses of Eimeria tenella-infected chickens. Poult. Sci.. 2004;83:1124-1132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Artemisinin and Artemisia annua leaves alleviate Eimeria tenella infection by facilitating apoptosis of host cells and suppressing inflammatory response. Vet. Parasitol.. 2018;254:172-177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalase, peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase activities during rice leaf senescence. Plant Physiol.. 1976;57:315-319.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physiological changes in the gastrointestinal tract and host protective immunity: learning from the mouse-Trichinella spiralis model. Parasitology. 2008;135:671-682.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proteomic comparison of four Eimeria tenella life cycle stages. Proteomics.. 2010;9:4566-14476.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eimeria vermiformis infection reduces goblet cells by multiplication in the crypt cells of the small intestine of C57BL/6 mice. Parasitol. Res.. 2009;104:789-794.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedic Reference of Parasitology (fourth ed.). Berlin: Springer Press; 2014.

- Anti-coccidial and anti-apoptotic activities of palm pollen grains on Eimeria papillata-induced infection in mice. Biologia. 2014;69:254-259.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of pine bark (Pious radiata) extracts on sporulation of coccidian oocysts. Folia Parasitol.. 2009;56:1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem.. 1979;95:351-358.

- [Google Scholar]

- Astragalus affects fecal microbial composition of young hens as determined by 16S rRNA sequencing. AMB Exp.. 2018;8:70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Astragalus membranaceus polysaccharide on the serum cytokine levels and spermatogenesis of mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;140:771-774.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of four murine Eimeria species in immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. J. Parasitol.. 1996;82:255-262.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman's reagent. Anal. Biochem.. 1968;25:192-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vivo anticoccidial activity of Salvadora persica root extracts. Pakistan J. Zool.. 2017;49:53-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protective effect of L-cysteine and glutathione on the modulated suckling rat brain Na+, K+, ATPase and Mg2+-ATPase activities induced by the in vitro galactosaemia. Pharmacol. Res.. 2004;495:475-479.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-coccidial properties and mechanisms of an edible herb, Bidens pilosa, and its active compounds for coccidiosis. Sci. Rep.. 2019;9:2896.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subchronic toxicity studies of Radix Astragali extract in rats and dogs. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2007;110:352-355.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mesorhizobium silamurunense sp. nov., isolated from root nodules of Astragalus species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.. 2012;62:2180-2186.

- [Google Scholar]