In vitro activity against multi-drug resistant bacteria and cytotoxicity of lichens collected from Mount Cameroon

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, P.O. Box 63 Buea, South West Region, Cameroon. njutain.moses@ubuea.cm (Moses N. Ngemenya)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Natural products remain a promising source of new efficacious antimicrobials to counter increasing resistance and prevent emergence of multidrug and extensively resistant bacteria phenotypes which hinder successful chemotherapy. Lichens have been shown to possess significant antimicrobial activity. This study investigated the antibacterial properties of six lichens found on Mount Cameroon. Methanol extracts of the lichens were screened against nine multidrug resistant clinical bacteria isolates and 6 control strains using disc diffusion and microdilution assays. The phytochemical composition of the extracts was determined and active extracts evaluated for cytotoxicity on monkey kidney epithelial LLC-MK2 cells using microscopy and MTT-formazan assay. Three extracts showed intermediate to high activity with diameters of inhibition zones ranging from 15 to 30 mm against all nine multidrug resistant strains similar to gentamicin positive control (P = 0.1018–0.6699). Extracts of Usnea articulata and Usnea florida, were the most active with minimum inhibitory concentrations of 4–10 mg/mL and showed broad spectrum dose-dependent activity. All the extracts were not cytotoxic (CC50 from 56.58 to 278.50 µg/mL) and the most active were rich in alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids among others. The considerable broad spectrum bacteriostatic activity against multidrug resistant strains and lack of cytotoxicity of U. articulata and U. florida justifies further exploration of these lichens to identify the bioactive molecules for development into new efficacious antibacterials.

Keywords

Lichens

Antibiotics

Resistance

Antibacterials

Toxicity

Phytochemistry

1 Introduction

Presently the use of antibiotics faces two challenges. Firstly antibiotic chemotherapy is seriously threatened with clinical failure due to emergence of resistance to antibiotics, which is now a major public health threat (WHO, 2016). Resistance has emerged in almost all classes of antibiotics over time and the magnitude in pathogenic bacteria of importance continues to increase resulting in multi-drug resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pan-drug resistant bacteria phenotypes (Ventola, 2015, Magiorakos et al., 2012). The pathogenic bacteria that are highly resistant include Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Enterobacteriaceae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Magiorakos et al., 2012). Resistance is particularly high with up to 100% resistance to some antibiotics in the African region where Cameroon is found; the high rates attributed to indiscriminate use of antibiotics in this region (Essack et al., 2016). Secondly, the impact of resistance is further compounded by the scarcity of new antibiotics; only two new classes (oxazolidinone and cyclic lipopeptide) have been introduced into clinical use in the last two decades though a couple of dozen antibiotics are in various phases of clinical development (Coates et al., 2011). Hence there is a need for novel antibacterial agents.

Multiple approaches are being employed in the discovery of new antibiotics which include medicinal synthetic chemistry, screening of compound libraries and drugs used to treat other diseases, molecular biology techniques involving metagenomics and functional screening, combinatorial biosynthesis to generate libraries of hybrid molecules, exploration of natural products among others. Natural products have a high potential of affording a wide variety of not readily synthesizable diverse structures hence are the most promising in yielding new antibiotic classes (Penesyan et al., 2015).

Lichens have been shown to have several properties with potential benefits to human health. Lichens are not single organisms but composed of fungal filaments, in symbiotic association with alga cells, usually a green algae or a cyanobacterium. They are slow growing and found in a wide variety of natural habitats or in places with low temperatures, prolong darkness; drought and continuous sunlight. (Shrestha and St. Clair, 2013). They are rich in secondary metabolites and are used for several purposes including medicinal, food, ritual and spiritual, aesthetics and decorative, ethno- veterinary, manufacture of Litmus indicator among others (Devkota et al., 2017; Mitrović et al., 2011). Lichens have been used for centuries to treat a wide variety of ailments including infections which is well documented (Shrestha and St. Clair, 2013; Crawford, 2015). Several studies on lichens natural products both crude extracts and isolated pure compounds have demonstrated medicinal properties including antibiotic, anticancer, antiviral among others (Shrestha and St. Clair, 2013). Some studies on their antibacterial activity have reported promising activity of crude extracts and pure compounds against bacteria including multi-drug resistant strains (Segatore et al., 2012; Manojlovic et al., 2012). Information and studies on lichens found in Cameroon are very limited. In one study, a DNA-based identification of lichen fungi forming species on lava flows on Mount Cameroon, 44 out of 58 lichen species were identified using basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) similarity search (Orock et al., 2012). Sequences relating to these species were till then not available in public databases. This study focused on some of these lichens which have not been extensively studied particularly for antibacterial activity and toxicity.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation and phytochemical analysis of extracts

All the lichens were collected in April 2016 from Mount Cameroon found in the Southwest of Cameroon and one of them also collected at Ekona, a village at the foot of the mountain. They were collected by Dr. Ayuk Elizabeth Orock, a Lichenologist in the Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of Buea. The lichens include Usnea articulata, Usnea florida, Leptigium gelatinisum, Physcia parietina, Ramalina sinensis and Xanthoparmelia plitti. Crude extracts were prepared as previously described (Mbah et al., 2012). The lichens were chopped, air-dried under laboratory conditions at room temperature for two weeks. Each dried material was ground to fine powder, weighed and macerated in methanol then filtered through Whatman filter paper No.1 into weighed bottles and kept to dry at room temperature. Maceration was done four times for three days each for plant materials available in small quantities to increase yield. The filtrate was evaporated (Rotavapor BÜCHI R-200), the extracts kept at room temperature to dry to constant mass, then weighed and stored at 4 °C until tested. Phytochemical tests were performed for presence of secondary metabolites in the extracts as described by Hossain et al., (2013). Briefly about 1 g of each extract was dissolved in the appropriate solvent and reacted with corresponding reagents to detect specific functional groups. The Dragendorff test showed an orange spot for alkaloids; the cyanidin test produced a dark red coloration for flavonoid; the Liebermann-Burchard test showed blue green indicating steroids and reddish coloration for terpenoids; persistent foam was seen in the frothing test showing saponins and the ferric chloride test produced a blue black coloration indicating presence of tannins.

2.2 Bacterial cells

Clinical strains of bacteria were obtained from the Regional Hospital Annex Buea, South West Region of Cameroon. They were identified by culture and biochemical tests using API 20E test kit (Biomérieux, France), and the cells stored in 10% sterile glycerol in Mueller Hinton Broth (Liofilchem, Italy) at −20 °C until use. Six control strains were included namely Escherichia coli KTE 181 (NR 32771), NR-515 Salmonella choleraesius and NR-4311 Salmonella enterica, NR-46003 Staphylococcus aureus strain 315, NRS-848 Staphylococcus epidermidis, were obtained from BEI Resources and P. aeruginosa Boston 41501 (ATCC 27853) from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, USA).

2.3 Antibacterial susceptibility test

The Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI, 2012) was employed as previously described (Akoachere et al., 2014) with some modifications. A uniform spread of bacterial cells on Mueller–Hinton agar was made using 100 μL of McFarland 0.5 (approximately 1.5 × 108 CFUs/mL) bacterial suspension. Plates were allowed to dry for 3–5 minutes. Discs of twelve reference antibiotics (LiofilChem, Italy), were embedded on the surface of the bacteria spread. Plates were incubated at 37 °C in a heating incubator (DHP-9052, England) for 18 to 24 h and diameter of zones of inhibition measured.

2.4 Determination of antibacterial activity

This was done as previously described by Mbah et al., (2012) with some modifications. A 10 mg/100 μL solution of each lichen methanol extract was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Sterile paper discs (6 mm diameter) were gently fixed on agar plates prepared as in the Kirby-Bauer method above. Ten (10) microlitres of test solution containing 1 mg extract was transferred on to the corresponding disc. Gentamicin standard disc (10 μg) and 10 μL of DMSO were included as positive and negative controls respectively. The plate was incubated at 37 °C (DHP-9052, England) for 18–24 h and diameter of zone of inhibition measured.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined as previously described (Mbah et al., 2012) with some modifications. Briefly, extract stock solutions were prepared by completely dissolving 40 mg of crude extract in 200 μL of DMSO and 800 μL of Mueller Hinton (MH) broth added and mixed. Each stock was diluted in MH broth to give 32, 24, 16, 8, 4, 2, and 1 mg/mL test solutions (final test range 0.25 to 10 mg/mL). The microtire plate wells comprised 50 μL of extract test solution or gentamicin (50 μg/mL) positive control,130 μL of MH broth containing bromothymol blue indicator followed by 20 μL of bacteria suspension (6.0 × 106 CFUs/mL) to all required wells. Saline (50 μL of 0.85%) was added to the negative control. The optical densities (OD) of wells were read at 595 nm (Emax microplate reader, Molecular Devices, USA). The plates was incubated at 37 °C (DHP-9052, England) for 24 h, read visually for inhibition and the OD read again. All experiments were done in duplicate. Percentage inhibition of bacteria cell growth after 24 h of incubation was calculated using the formula:

MIC was taken as the lowest concentration which showed >50% inhibition of bacterial growth. For minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) assay required well contents were mixed and 20 μL of MIC well diluted in 180 μL of fresh medium. The OD was read before and after incubation as above. The percentage growth of bacteria cells was calculated using the following formula and MBC was recorded as the lowest concentration of MIC wells with <50% growth.

2.5 Cytotoxicity test

All reagents used were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (USA). RPMI-1640 complete culture medium (CCM) containing sodium bicarbonate was supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 0.3g gamma-irradiated L-glutamine powder, 5%heat inactivated new born calf serum (NBCS), 200 units/mL penicillin and 200 μg/mL streptomycin and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B, pH 7.4. Monkey kidney epithelial cells (LLC-MK2; ATCC, USA) were cultured (37 °C, 5% CO2 in humidified air; Heracell150i, USA) to confluence using standard protocol and trypsinized to dislodge, centrifuged in incomplete culture medium (ICM, without NBCS) as above and re-suspended in CCM and counted by microscopy. The cells (3000 cells/ 100 μL in CCM) were seeded into 96-wells flat bottom microtitre plate (Becton Dickinson,) and incubated same for 3 days to grow and become fully confluent.

Cytotoxicity assay was done as described (Nondo et al., 2015) with some modifications. Briefly, 25 mg/mL extract stock was prepared in DMSO and 2 mg/mL serially diluted to 1000–15.625 µg/mL test concentration range. Then 100 µL test solution was added to corresponding wells with cells and incubated for five days. Negative control, NC (cells in medium and 2% DMSO without extract) and positive control (30 μM auranofin) were also included. The shape and appearance of the cells were examined microscopically daily for five days. Viability of the cells was assessed using the formazan assay. The plate was washed with ICM to decolorize wells by shaking three times at 600 RPM for five minutes at 37 °C in an incubator. MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide] solution (100 μL) was added into the wells, the plate incubated for 2 h and 100 μL DMSO added to solubilise the formazan precipitate. The plate was shaken at 400 RPM for five minutes at 37 °C inside an incubator and optical density (OD) of wells read at 595 nm (Emax microplate reader). Percentage inhibition of formazan formation was calculated using the formula

2.6 Data analysis

Zone diameters from susceptibility test and antibacterial screening by disc diffusion were interpreted based on Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute reference data for the corresponding antibiotics (CLSI, 2012). The T- test performed using the MedCalc software version v8.0.0.1 was used to compare the zone diameters of the extracts to that of the gentamicin positive control with significance taken at P < 0.05. To determine minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), the experiment was considered valid only when both bacterial growth in the negative control was >50% and the positive control showed an inhibition of >50% after 24 h incubation compared to the baseline at 0 h. The MIC was determined by plotting percentage inhibition against concentration using Microsoft Excel 2010 and the MIC value interpolated from the curve. Data from cytotoxicity assay were analyzed using Graph pad prism version 6.0 and the concentration of extract that produced 50% cytotoxic effect on Monkey kidney epithelial cells CC50 recorded.

3 Results

3.1 Yield and phytochemical composition of extracts

The weights of the dried extracts were recorded and yield calculated as shown on Table 1. U. articulata is rich in four classes of phytochemicals (alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids and steroids). U. florida has high amounts of saponins and steroids while Xanthoparmelia plitti similarly is rich in terpenoids and saponins.

| Lichen Species | Yield of extracts (g) (% w/w) | Phytochemical constituents (relative amounts) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Flavonoids | Triterpenoids | Saponins | Steroids | Tannins | ||

| Usnea articulata | 3.84 (3.9) | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | + |

| Usnea florida | 4.59 (4.3) | ++ | ++ | − | +++ | +++ | − |

| Ramalina sinensis | 0.21 (0.62) | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Leptigium .gelatinisum | 0.14 (0.54) | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Xanthoparmelia plitti | 2.11 (3.1) | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | − |

| Physcia parietina | 0.21 (0.49) | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd |

Relative amount of phytochemical:- +, trace; ++, moderate; +++, high. − Nd: not done due to insufficient yield

3.2 Antibiotic susceptibility of test bacteria

The sixteen bacterial strains (six controls and ten clinical isolates) showed inhibition zones ranging from 7 to 37 mm for twelve antibiotics belonging to eight chemical classes (Table 2). Nine of the ten clinical isolates were multidrug resistant with P. rettgeri being the most resistant to at least one molecule of six antibiotics classes. All clinical isolates were susceptible to the aminoglycosides (gentamicin and amikacin) while resistant to the cephalosporins (cefuroxime and cefotaxime). Eight and seven of the isolates were susceptible to the quinolones, ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin, respectively while 7 of the isolates were susceptible to nitrofurantoin and chloramphenicol. Five and four isolates were susceptible to imipenem and ceftriaxone respectively. Three of the bacterial isolates were susceptible to tetracycline and trimethoprim. Four control strains, E. coli, S. enterica, S. aureus and S. epidermidis, were multidrug resistant but were also susceptible to the aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones like the clinical isolates.

| Bacteria strains | Diameter of zone of inhibition (mm) | Resistant antibiotic classes (n) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK | GN | CRO | CXM | CT | C | CIP | NOR | IMI | NIT | TE | TRI | ||

| E. cloacae | 23 | 17 | 15r | – | – | 24 | 30 | 30 | 15 r | 16 | – | 27 | 3 |

| E. coli | 25 | 18 | – | – | – | 22 | – | 10r | 25 | 30 | – | – | 4 |

| C. freundi | 27 | 24 | – | – | – | 23 | 30 | 32 | – | 25 | 15 | – | 3 |

| C. youngae | 30 | 28 | – | – | – | 27 | 31 | 31 | – | 25 | – | 11 | 3 |

| Citrobacter sp | 19 | 16 | 17r | – | – | 21 | 20 | 26 | – | 22 | 16 | 30 | 2 |

| P. mirabilis | 20 | 20 | 23 | – | – | – | 37 | 36 | – | 14 r | – | 22 | 4 |

| P. rettgeri | 20 | 19 | – | – | – | – | 25 | 27 | – | – | – | – | 6 |

| P. vulgaris | 20 | 16 | 25 | – | – | 30 | 28 | 30 | 15 r | 14 r | – | – | 5 |

| S. typhi | 19 | 20 | – | – | – | – | 25 | 25 | – | 15 | – | – | 5 |

| Salmonella sp | 20 | 15 | – | – | – | 23 | 36 | 37 | 18 r | 18 | 17 | – | 3 |

| E. coli ф | Nd | 20 | 8r | Nd | Nd | 29 | 26 | 30 | 8r | 22 | 8r | 8r | 4 |

| P. aeruginosa ф | Nd | 24 | NI | Nd | Nd | 18 | 30 | 24 | – | 20 | 20 | NI | 1 |

| S. choleraesius ф | Nd | 22 | 20 | Nd | Nd | 30 | 20 | 28 | – | 21 | 19 | – | 2 |

| S. entrica ф | Nd | 19 | – | Nd | Nd | 25 | 29 | 27 | 9r | 9r | 19 | 11 | 3 |

| S. aureus ф | Nd | 21 | 8r | Nd | Nd | 15 | 22 | 19 | 7r | 12r | 19 | 7r | 4 |

| S. epidermidis ф | Nd | 22 | 10r | Nd | Nd | 28 | Nd | 19 | – | 7r | 28 | 29 | 3 |

n: number of antibiotic classes to which bacteria are resistant based on reference zone diameters (CLSI, 2012). ф Control strains; the others are clinical isolates. Nd: not done. NI: antibiotics not indicated for susceptibility testing (CLSI, 2012). r, - (0 mm zone of inhibition), both indicate resistant strain. Aminoglycosides (AK, Amikacin; GN, Gentamicin). Cephems (CRO, Ceftriaxone; CXM, Cefuroxime; CT, Cefotaxime). Phenicols (C, Chloramphenicol). Fluoroquinolone (CIP, Ciprofloxacin; NOR, Norfloxacin). Carbapenems (IMI, Imipenem). Nitrofurans (NIT, Ntrofurantoin)…Tetracyclines (TE, Tetracycline). Folate Pathway Inhibitors (TRI:,Trimethoprim).

3.3 Antibacterial activity of crude extracts

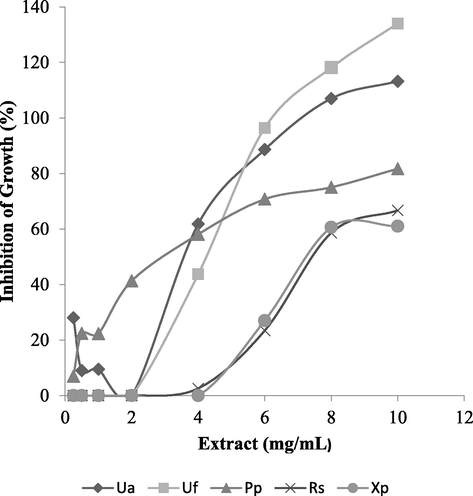

All the six extracts were active against at least two bacterial strains with diameter of zones of inhibition ranging from 9 to 30 mm for clinical isolates and 7 to 29 for control strains (Table 3). Extracts of three lichens (U. articulata, U. fllorida and R. sinensis) were highly active (zones ≥ 20 mm,) against at least five of both control and clinical strains; the other three showed weak activity. Overall, U. articulata, and U. fllorida, were the most active. All bacterial isolates were susceptible (zones ≥ 20 mm) to gentamicin except for one which was moderately sensitive (zone = 18 mm) as shown on Table 3. Statistical analyses (T-test) showed that the activities of U. articulata, U. fllorida and R. sinensis in the diffusion test was similar to the gentamicin positive control (P = 0.1018 to 0.6699) whereas the gentamicin was more active than the other three extracts (P < 0.0001) shown on Table 3. In the MIC experiments, growth of negative control ranged from 124 to 200%; and inhibition in positive control containing gentamicin ranged from 79.3 to 91.6%. Based on the criteria stated under data analysis above, the MICs ranged from 4 to 10 mg/mL. The lowest MIC (4 mg/mL) was produced by two lichens, U. articulata and P. parietina. Overall the highest number of MICs was recorded for U. articulata and U. florida, against five organisms while no MIC was observed for L. gelatinisum in the concentration range tested (Table 4). U. articulata and U. florida, produced MICs against four clinical and one control strain each. MICs were recorded for at least two lichen extracts against each strain and the highest was four extracts with MIC values against E. coli (Table 4). The active extracts showed broad spectrum bacteriostatic activity against seven Gram-negative bacteria which was dose-dependent as illustrated for the lowest MICs in Fig. 1. No MIC was recorded against Gram-positive S. aureus (not shown on Table 4). No MBC was recorded for all the extracts.

| Bacteria Strain | Lichen extracts | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ua | Uf | Rs | Lg | Pp | Xp | GN | TE | C | |

| Diameter zone of inhibition (mm) | |||||||||

| E. cloacae | 24 | 25 | 17 | – | – | – | 27 | 16 | Nd |

| E. coli | 19 | 27 | 18 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 22 | Nd | Nd |

| C. freundi | 13 | 19 | 21 | – | 11 | 12 | 23 | 15 | Nd |

| C. youngae | 16 | 16 | 24 | – | – | – | 24 | 10 | Nd |

| P. mirabilis | 22 | 21 | 18 | – | 10 | 11 | 22 | Nd | Nd |

| P. rettgeri | 19 | 23 | 22 | – | 11 | 10 | 21 | Nd | Nd |

| P. vulgaris | 21 | 29 | 25 | 11 | – | – | 24 | 10 | Nd |

| S. typhi | 26 | 23 | 26 | – | 11 | – | Nd | Nd | 27 |

| S. aureus | – | 30 | Nd | – | 9 | 14 | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| E. coli ф | 7 | – | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | 23 | Nd | Nd |

| P. aeruginosa ф | 28 | 18 | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | 26 | Nd | Nd |

| S. choleraesius ф | 9 | 12 | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | 20 | Nd | Nd |

| S. entrica ф | – | – | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | 18 | Nd | Nd |

| S. aureus ф | 29 | 25 | 22 | Nd | Nd | Nd | 29 | Nd | Nd |

| S. epidermidis ф | – | – | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | 21 | Nd | Nd |

| Activity* | Frequency (n) | ||||||||

| Highly active (≥ 20 mm) | 6 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | Na | Na |

| Moderately active (15–19 mm) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Na | Na |

| Weak activity (> 6 ≤ 14 mm) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 0 | Na | Na |

| Inactive | 3 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 0 | Na | Na |

| Total | 15 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 13 | Na | Na |

| T –test (P value) | =0.1018 | = 0.6699 | =0.2375 | <0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |||

Lichens species: Ua: Usnea articulata ; Uf: Usnea florida ; Rs: Ramalina sinensis; Lg: Leptigium gelatinisum; Pp: Physcia parietina; Xp: Xanthoparmelia plitti. Positive control antibiotics:- GN: Gentamicin; TE: Tetracycline; C: Chloramphenicol. ф: Control strains,-: no zone of inhibition observed. Nd: not done. * Activity category deduced from data for reference antibiotics (CLSI, 2012). Na: Not applicable

| Extract code | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (mg/mL) | CC50 (µg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | C. freudi | C. youngae | P. mirabilis | P. rettgeri | S. typhi | S. enterica ф | ||

| Ua | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 | Nil | Na | 8 | 62.4 |

| Uf | 8 | 5 | 6 | 9 | Nil | Na | 10 | 56.6 |

| Rs | − | Nd | Nd | Nd | 8 | 10 | Nd | 90.3 |

| Lg | − | − | − | − | − | 278.5 | ||

| Pp | 4 | Nd | Nd | Nd | 8 | 4 | Nd | 92.3 |

| Xp. | 10 | Na | Na | − | 7 | 9 | Nd | 190.8 |

Extract code:- Ua: Usnea articulata ; Uf: Usnea florida ; Rs: Ramalina sinensis; Lg: Leptigium gelatinisum; Pp: Physcia parietina; Xp: Xanthoparmelia plitti. ф Control strain.

Data are from experiments with >50% growth in negative control and > 50% inhibition in positive control (gentamicin) after 24 h incubation compared to baseline at 0 h. −: no or < 50% inhibition at highest concentration (10 mg/mL) tested. Na: not considered as inhibition in positive control was <50%. Nd: not done. CC50: cytotoxic concentration for 50% of cells; CC50 > 30 µg/mL: cut-off for negligible cytotoxicity (Hossain et al., 2013).

- Dose-dependent inhibition of bacterial growth by methanol crude extracts of lichens. Minimum inhibitory concentration is the lowest concentration which shows > 50% inhibition of growth. Ua: Usnea articulata against C. youngae; Uf: Usnea florida against C. freundi; Pp: Physcia parietina against S. typhi; Rs: Ramalina sinensis against P. rettgeri; Xp: Xanthoparmelia plitti against P. rettgeri.

3.4 Cytotoxicity of extracts

Cytotoxicity profile was evaluated on monkey kidney epithelial cells in the range 15.625 to 1000 μg/mL. The CC50 of the extracts were all >30 μg/mL, the cut point for lack of cytotoxicity (Ogbole et al., 2017) as shown on Table 4. This suggests a low risk of toxicity on mammalian cells. U. articulata and U. fllorida, the most active lichens, had relatively lower CC50 values while L. gelatinisum and X. plitti had the highest CC50 values hence were least cytotoxic.

4 Discussion

The antimicrobial properties of lichens including antibacterial activity have been demonstrated in several studies. This study of lichens found on Mount Cameroon has revealed that two of the six lichens, Usnea articulata and Usnea florida possess considerable activity against multidrug resistant bacteria and low risk of cytotoxicity to mammalian cells. These findings demonstrate the potential of these lichens as promising sources of new antibacterials. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study on the antibacterial activity of these lichens (except Usnea florida and R. sinensis) and their cytotoxicity (except Usnea florida).

Following antibacterial susceptibility tests multidrug resistance was observed in nine clinical isolates of bacteria cells with only one isolate not found to be multidrug resistant (Table 2). The isolates satisfied two criteria to be classified multidrug resistant. Firstly the isolate is resistant to at least one antibiotic in three or more antibiotic classes (Magiorakos et al., 2012) and secondly the antibiotic is indicated for susceptibility testing against the species of the isolate according to the CLSI (2012). This finding confirms that of the Medical Laboratory of the Buea Regional Hospital Annex, the source of the clinical isolates, where isolates were initially found to be resistant following susceptibility tests. This also indicates multidrug resistance in the study area as earlier reported (Akoachere et al., 2014). The clinical isolates were particularly resistant to the cephem antibiotics but still largely susceptible to the aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones. However, considering this trend there is a likelihood of these phenotypes developing resistance to these active molecules giving rise to extensively resistant phenotypes in the study area, further aggravating morbidity and mortality from their infections. This prevailing situation justifies the search for new efficacious and safe antibiotics.

Based on the zones of inhibition, crude extracts of U. articulata, U. florida, and R. sinensis all had high activity against most test organisms including control strains (Table 3). This finding which is comparable to the gentamicin positive control (P = 0.1018–0.6699) is primary evidence that these extracts may be a good source of new antibacterials. Overall two extracts (U. articulata and U. florida) were the most active with MICs of 4–10 mg/mL against five strains. Results of the microdilution and diffusion experiments were generally consistent. However R. sinensis showed high activity in the diffusion test while Physcia parietina was also more active in the MIC assay; this difference is probably due to the differences in chemical properties of the component secondary metabolites and the experimental systems. The results of the micro-dilution assay confirm that the active lichens have broad spectrum bacteriostatic activity against Gram-negative bacteria (Table 4). Furthermore the activity in the MIC assay was dose-dependent (Fig. 1) suggesting that the active lichens contain bioactive secondary metabolites which are potential antibacterials.

A study (Cankılıç et al., 2017) reported very high antibacterial activity for Usnea florida and moderate activity of thamnolic acid isolated from it, while Çobanoğlu et al., (2016), reported no or weak antibacterial activity for methanol extracts of Usnea florida. Shrestha also reported high activity for R. sinensis. Various MICs have been reported for different species of lichens. Manojlovic et al., (2012) recorded much lower values (15.62–62.50 μg/mL) for Umbilicaria cylindrical while Kosanic and Rankovic, (2011) reported values relatively close to those in this study (0.78 to 6.25 mg/mL) for Cladonia furcata, Hypogymnia physodes, and Umbilicaria polyphylla. Differences in reported activities may be due to site of collection, phytochemical composition and some methodological differences. The high antibacterial activity observed with these extracts may be accounted for by secondary metabolites such as usnic acid, barbatic acid, lecanoic acid, antranolin, salazinic acid, stictic acid, physodic acid amongst others, which have been previously isolated from the Usnea and Ramalina genera and reported to possess good antibacterial activity (Kosanic and Rankovic, 2011; Martins et al., 2010). The activity recorded in this study may be accounted for by some of these metabolites acting independently or in synergy; but this remains to be demonstrated experimentally.

Following phytochemical analysis, relatively high amounts of alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids and steroids were detected in U. articulata extract while U. florida extract was rich in saponins and steroids (Table 1). The phytochemistry of three of the lichens (Ramalina sinensis, Leptogium gelatinisum, Physcia parietina) and their secondary metabolites remains to be fully established. The cytotoxicity test revealed that all the extracts were not cytotoxic as their CC50 values were all >30 μg/mL (Table 4), the cut-off value for cytotoxic effect in 50% of the cells (Ogbole et al., 2017). This finding is similar to that of Karagöz et al., (2009) who reported CC50 ranging from 20 to 450 μg/mL for ethanol extracts of eleven lichens on Vero cell lines. This finding indicates a low risk of toxicity to mammalian cells, suggesting their secondary metabolites may not be toxic and justifies further study of these lichens as potential sources of new efficacious antibacterials.

5 Conclusion

U. articulata and U. florida showed promising broad spectrum bacteriostatic activity against multidrug resistant strains of bacteria and low risk of cytotoxicity hence their bioactive molecules should be isolated and investigated for antibacterial activity. Furthermore the efficacy of the crude extracts of these active lichens should be evaluated using an in vivo model of bacterial infection.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PNNB: bench experiments. AEO: collection and identification of lichens. KDN and SBB: preparation of extracts, phytochemical tests, drafting the manuscript. AK: isolation and characterization of clinical bacteria cells. MNN: conception and study design, supervision of experiments, drafted manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The work was funded under the University of Buea 2016 Budget with assistance from the Biotechnology Unit of the same institution. Mr. Mbaabe Felix of the Life Sciences Laboratory provided technical assistance with bacterial cultures.

References

- Risk factors for wound infection in health care facilities in Buea, Cameroon: aerobic bacterial pathogens and antibiogram of isolates. Pan. Afr. Med. J.. 2014;18(6)

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of antibacterial, antituberculosis and antifungal effects of lichen Usnea florida and its thamnolic acid constituent. Biomed. Res.. 2017;28:3108-3113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty second informational supplement M100–S22. Wayne, 2012. http://antimicrobianos.com.ar/ATB/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/M100S22E.pdf (accessed 15.12.16.).

- Novel classes of antibiotics or more of the same? Br. J. Pharmacol.. 2011;163:184-194.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of the lichens Physcia aipolia, Xanthoria parietina, Usnea florida, Usnea subfloridana and Melanohalea exasperata. Modern Phytomorphology. 2016;10:19-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lichens Used in Traditional Medicine. In: Rankovic B., ed. Lichen Secondary Metabolites Bioactive properties and Pharmaceutical potential. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 27–80

- [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous knowledge and use of lichens by the lichenophilic communities of the Nepal Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed.. 2017;13:15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial resistance in the WHO African region: current status and roadmap for action. J. Public. Health.. 2016;39:8-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of total phenol, flavonoids contents and phytochemical screening of various leaves crude extracts of locally grown Thymus vulgaris. Asian. Pac. J. Trop. Biomed.. 2013;3:705-710.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity of some lichen extracts. J. Med. Plants. Res.. 2009;3:1034-1039.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of some lichens and their constituents. J. Med. Food.. 2011;14:1624-1630.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.. 2012;18:268-281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of Lichen Umbilicaria cylindrica (L.) Delise (Umbilicariaceae) Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med.. 2012;2012:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cladia aggregata (lichen) from Brazilian northeast: chemical characterization and antimicrobial activity. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol.. 2010;53:115-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioassay-guided discovery of antibacterial agents: in vitro screening of Peperomia vulcanica, Peperomia fernandopoioana and Scleria striatinux. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob.. 2012;2012(11):10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic discovery: combatting bacterial resistance in cells and in biofilm communities. Molecules. 2015;20:5286-5298.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the cytotoxic activity of extracts from medicinal plants used for the treatment of malaria in Kagera and Lindi regions, Tanzania. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci.. 2015;5:007-012.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro cytotoxic activity of medicinal plants from Nigeria ethnomedicine on Rhabdomyosarcoma cancer cell line and HPLC analysis of active extracts. BMC. Complement Altern. Med.. 2017;2017(17):494.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA-based identification of lichen-forming fungi: can publicly available sequence databases aid in lichen diversity inventories of Mount Cameroon (West Africa)? Lichenologist. 2012;44:833-839.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro interaction of usnic acid in combination with antimicrobial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates determined by FICI and DE model methods. Phytomedicine. 2012;19:341-347.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lichens: a promising source of antibiotic and anticancer drugs. Phytochem. Rev.. 2013;12:229-244.

- [Google Scholar]

- The antibiotics resistance crisis. Part 1: Causes and threats. Pharm. Ther.. 2015;4:277-283.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2017. Antimicrobial resistance Fact sheet Updated September 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/ (accessed on 24 .06.17).