Translate this page into:

Green synthesis of Cerium oxide / Moringa oleifera seed extract nano-composite and its molluscicidsal activities against biomophalaria alexanderina

⁎Corresponding author. guraishi@yahoo.com (Saleh Al-Quraishy)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The green synthesis method is one of the most economic and ecofriendly approach for preparation of metal oxide nanoparticles. In the current study, Moringa oleifera seed was used for synthesis of Ce2O3/M. oleifera (Ce2O3/MNCs) nano-composite. The bio-composite was characterized using FT-IR, XRD, SEM and HR-TEM. The FTIR analysis confirmed the phytochemical involvement in bio-composite. Its crystalline and size was well demonstrated through X-ray Diffraction and HR-TEM. The TEM images revealed these particles in circle shape with average size of 30 nm. The present investigation showed that Ce2O3/MNCs was toxic to B. alexandrina snails with LC50 of 314.5 mg/L. The survival and the reproductive rates of the snails were significantly reduced after exposing to ¼ and ½ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs. The present study showed that Ce2O3/MNCs has significant ovicidal and larvicidal activities. Also, the exposure to ½ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs showed alterations in the tegmental architectures of the head-foot region, in addition it caused significant damages in both of the hermaphrodite and digestive glands of B. alexandrina. Conclusively, Ce2O3/MNCs nano-composite could be utilized as a new molluscicidal agent for the snails of schistosomiasis.

Keywords

Cerium oxide/ Moringa oleifera nano-composite

Nanoceria

Schistosomiasis

Molluscicide

1 Introduction

Phytosynthesis of metal and their oxide nanoparticles (NPs) has gained a great interest as it is safe, cost-effective, and eco-friendly method (Singh et al., 2018). Cerium oxide nanoparticles, nanoceria, (Ce2O3 NPs) has received much consideration as a reliable photo-catalysts, oxygen sensors, ultraviolet absorbent, and as a possible therapeutic alternative in biology and medical sciences (Charbgoo et al., 2017). Several studies confirmed the synthesis of cerium oxide nanoparticles using green methods from the leaf extract of Acalypha indica, Gloriosa superba and Aloe vera (Rajeshkumar & Naik, 2018).

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease caused by blood flukes (trematode worms) of the genus Schistosoma and it is recognized as leading cause of significant mortality and morbidity worldwide (Augusto and de Mello-Silva, 2018). Snails of the genus of Biomphalaria are the intermediate host for Schistosoma mansoni (Ibrahim and Sayed, 2019). Thus, the elimination or control of snails may be an alternative approach to control and to interrupt the transmission of schistosomiasis (Omobhude et al., 2017). Chemical molluscicides are the most common approach to control snails for prevention of Schistosoma transmission (King and Bertsch, 2015). Currently, the application these molluscicides is hampered by their high cost, toxicity to non-target organisms and environmental hazards (Mandefro et al., 2017). Recently, nanomaterials have been proven to have molluscicidal activities either due to their toxic effect or/and due to its ability to reduce the snail fertility (Ali et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2019). Nowadays, several studies highlighting the potential of biogenic nanoparticles compared to their chemically made analogs (Guilger et al., 2017; Xiong et al., 2018; Capeness et al., 2019).

It has been previously established that Moringa oleifera seed extract has potent molluscicidal and ovicidal activities against the snails of genus Biomphalaria (Ibrahim and Abdalla, 2017). As the Phytosynthesized Ce2O3 NPs have no side effects in biomedical applications (Charbgoo et al., 2017), our present investigation was therefore inspired additional investigation into the use of plant extracts for the synthesis of nanoceria from the M. oleifera seed extract. The present study was also, aimed to: (i) characterize M. oleifera phytosynthesized Ce2O3 NPs with using FTIR, XRD, SEM and TEM (ii) testify its molluscicidal activity and its effect on the biological systems of B. alexandrina snails (iii) evaluate its toxicity on the larval stages of S. mansoni.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of Cerium oxide / M. Oleifera nano-composite (Ce2O3/MNCs)

The collected M. oleifera seeds were dried at 50 °C in digital electrical drier for 48 h, and then grinded to size range from 1 mm to 0.2 mm. To obtain seed extract, 6 g of the grinded seeds were dispersed in 30 ml distilled water under stirring for 30 min at 70 °C. The obtained extract was mixed with 50 ml of CeSO4 (0.1 M) and warmed at 65 °C for 3 h. Then, it was left at room temperature overnight for precipitation Cerium oxide particles which was separated and washed several times by ethanol and distilled water. Finally, the fabricated Ce2O3/MNCs was dried at 60 °C for 12 h and then calcinated at 350 °C for 3 h.

2.2 Characterization of the Cerium oxide / M. Oleifera nano-composite (Ce2O3/MNCs)

Ce2O3/MNCs were characterized using X-ray diffraction pattern (a PANalytical (Empyrean) X-ray diffractometer), JEOL-JEM 2100 transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and Gemini, Zeiss-Ultra 55 scanning electron microscope (SEM). Meanwhile, FT-IR spectra were investigated with a Bruker (Vertex 70 FTIR-FT Raman) spectrometer.

2.3 Snails and larvae of schistosomiasis mansoni

Adult B. alexandrina snails, Schistosoma mansoni ova and cercariae were obtained from Theodor Bilharz Research Institute (TBRI). The snails were maintained in plastic aquaria and fed on oven dried lettuce leaves and TetraMin®. Water of the aquaria was changed once a week. For collecting the egg masses, pieces of polyethylene sheets were used.

2.4 Determination of the LC50 and LC90

Snails of B. alexandrina were exposed to different concentrations of Ce2O3/MNCs (200, 250,300,350 and 400 mg/L) for 48 h at room temperature (22–25 °C) to calculate the LC50 and LC90. Snails of the same size were exposed to dechlorinated water only and considered as the control group. Then, the snails were removed from the exposure solution, and maintained in dechlorinated tap water for 24 hr for recovery. The snails’ percent mortality was recorded (WHO, 1965). The lethal concentration and the slope values were estimated by Probit analysis. Three replicates of 10 snails were used for each concentration.

2.5 Effect of ¼ and ½ of the LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs on the survival and reproductive rates of B. Alexandrina

B. alexandrina snails were exposed to ¼ and ½ of the LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs for two weeks (24 h/d) while snails of the control group were maintained in dechlorinated water. The effects of these concentrations on the net reproductive rate (R0) of B. alexandrina snails were represented by the summation of survival rate (Lx) multiplied by the mean number of eggs/snail/week (Mx) during the experimental period as suggested by El-Gindy et al. (1965).

2.6 Scanning electron microscopic studies of the head foot region of B. Alexandrina

The head foot regions of snails were separated under a stereomicroscope. Then, the specimens were fixed, dehydrated, critically dried and coated as recommended by Ibrahim and Abdel-Tawab (2020). Finally, they were photographed by JSM-6510 LA.

2.7 Ovicidal activity

100 eggs of B. Alexandrina on polyethylene sheets were used and subjected to ¼ and ½ of the LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs for 24 h. Then, the eggs were transferred to petri dishes containing dechlorinated water and were examined daily for seven days under a stereomicroscope. Another 100 eggs in dechlorinated water were used as a control group.

2.8 Miracidicidal and cercaricidal activities

100 freshly hatched S. mansoni miracidia, and cercariae in 5 ml of water were mixed in a separated petri dish with 5 ml of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs. Another petri dish containing 10 ml dechlorinated tap water with either 100 freshly hatched miracidia or 100 freshly shed cercariae were kept as control (Abdel-Ghaffar et al., 2016). The motility of cercariae and miracidia were noticed by a dissecting microscope for any alterations. Immobile ones were supposed to be dead (Obare, 2016).

2.9 Histological evaluation of B. Alexandrina snail’s digestive and hermaphrodite glands

After two weeks of exposure and recovery, some B. alexandrina adult snails were selected randomly and dissected. The digestive and hermaphrodite glands were removed, and fixed in Bouin's solution. Glands were dehydrated and then embedded in paraffin wax. Finally, both gland were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Mohamed and Saad, 1990).

2.10 Statistics

The lethal concentration (LC10, LC25, LC50, and LC90) values, slop and the 95% Confidence limit (CL) of LC50 were calculated by Probit analysis (Finney, 1971) using SPSS v. 22.

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of the Cerium oxide / M. Oleifera nano-composite (Ce2O3/MNCs)

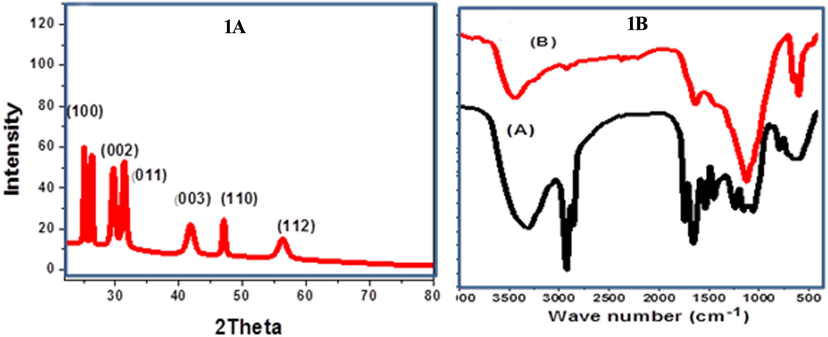

The polycrystalline nature of the biogenic Ce2O3/MNCs was confirmed by XRD pattern (Fig. 1A). The diffraction pattern is fitted well with the characteristic peaks of the pure Cerium oxide (Ce2O3, 00-044-1086). The phase structure of Ce2O3 was hexagonal with P-321 as a space group and its number 158. The lattice parameters were a = b = 3.891 Å and C = 6.0630 Å and cell volume unit was 79.5 × 106 pm3. The noticed diffraction pattern at 2θ = 26.5, 29.6, 30.5. The peaks of 44.8, 46.91, and 56.2 are regarding to the crystallographic planes (1 0 0), (0 0 2), (0 1 1), (0 0 3), (1 1 0), and (1 1 2) which can be matched to Ce2O3 pattern. The peak intensity in XRD diffraction elucidated the high crystallinity of the biogenic Ce2O3/MNCs. The crystallite size (D) were estimated using Scherrer equation (D = 0.9λ/W Cosθ), where W is the full width at half maximum in radians, θ is the Bragg’s angle, and λ is the X-ray wavelength (CuKα = 0.15405 nm). The estimated value of D was ∼ 30.5 nm. The lattice defects number of biogenic cerium oxide was investigated. The dislocation density was calculated according to Williamson and Smallman’s relation, δ = N/D2; where N equals unity in case of the minimum dislocation density. The estimated value of δ is10 × 10−4 dislocation/nm2. This small value of δ showed a good lattice structure for cerium oxide sample. FT-IR spectra of M. oleifera seeds and Ce2O3/MNCs were showed in Fig. 1B and Table 1. Both of them illustrated the characteristic functional groups of the studied structures.

Characterization of Ce2O3/MNCs. (1A) XRD patterns of Ce2O3/MNCs, (1B) FT-IR spectra of Moringa extract (A) and Ce2O3/MNCs nanostructure (B).

Absorption bands cm−1

M. oleifera seeds

Ce2O3/MNCs

3311

O-H stretching of fatty acids, carbohydrates and the lignin units and to N–H stretching

2923 and 2852

C–H symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibration in CH2

1750 and 1630

C=O connection stretching

1587

C–N stretching vibration and the deformation of the N–H starching vibration

3673 cm-1 and 1611

hydrogen bonded OH groups present in the aqueous phase

2350

CH stretching vibration

1362 and 1113 cm

Ce2O3 nanoparticles and C–O–C stretching

750,604 and 460

chemical interaction between Ce and oxygen

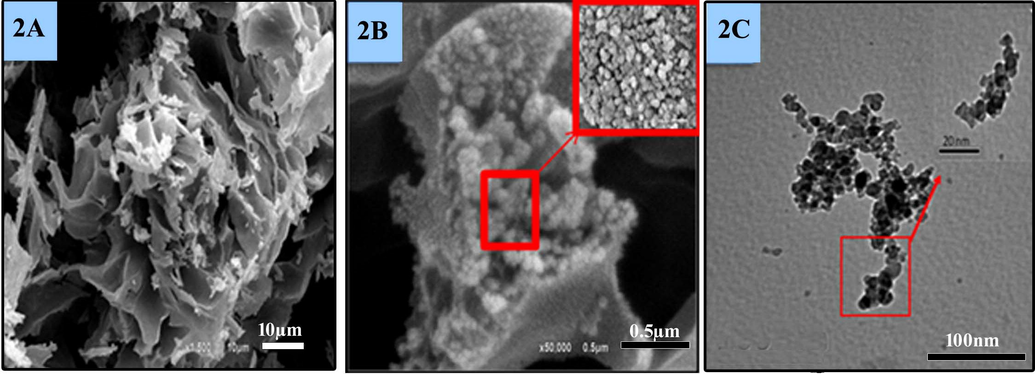

The morphological criteria of Moringa seeds and biogenic Ce2O3/MNCs were obsereved through the FE-SEM images (Fig. 2A, B). Moringa seed exrtact was appeared as layers that were wrapped to be like cabbage papers (Fig. 2A). The synthesized Ce2O3/MNCs were strongly agglomerated to form nanoparticles with a size ranged from 25 to 35 nm (Fig. 2 B) and with uniform nanoporous features which was shown in the magnified image (Fig. 2B). TEM revealed the Ce2O3/MNCs as crystalline stacked nanograins with circle like shapes and with average particles size ranged from 28.5 to 30 nm (Fig. 2C).

Electron microscopic characterization. (2A) SEM of the Moringa extract, (2B) SEM of the Ce2O3/MNCs, (2C) TEM of Ce2O3/MNCs.

3.2 Biological activities

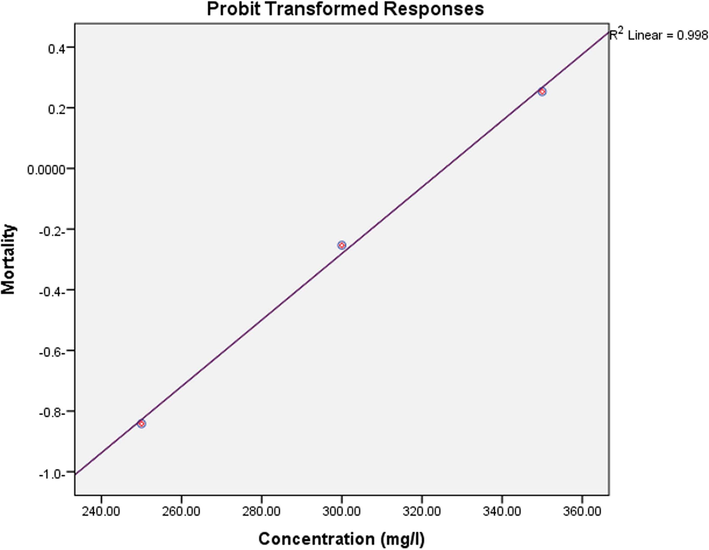

In the present study, Ce2O3/MNCs was tested for its molluscicidal activity against snails of B. alexandrina. Probit analysis showed that the LC50 was 314.5 mg/L while the LC90 was 386.5 mg/L (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Snails

LC10 (mg/L)

LC25 (mg/L

LC50 (mg/L)

Confidence limits of LC50 (mg/L)

LC90 (mg/L)

Slope

Biomphalaria alexandrina

242.6

276.7

314.5

271.1- 364.9

386.5

1.3

Molluscicidal activity of the tested Ce2O3/MNCs against adult B. alexandrina snail.

3.3 Effect of ¼ and ½ of the LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs on the survival and reproductive rates of B. Alexandrina

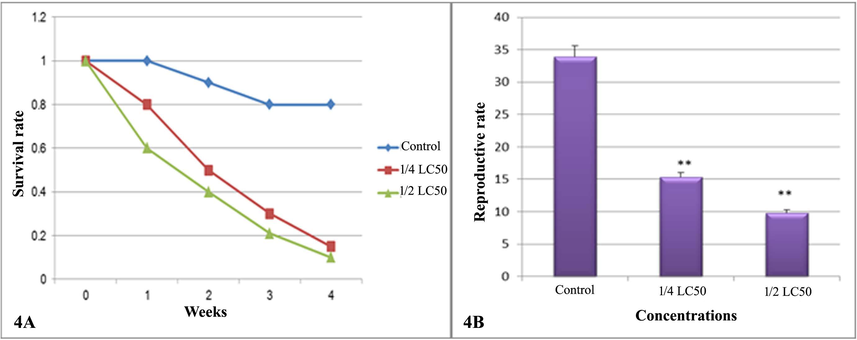

It was found that the survival rate of B. alexandrina snails was significantly reduced (p < 0.05) when compared with the control group after the treatment with doses of ¼ and ½ of the LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs in dose dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Also, the fecundity (MX) of snails was significantly reduced and this was associated with significant reduction (p < 0.01) in the reproductive rate (Ro) (Fig. 4B).

Survival and reproductive rates of B. alexandrina snails. (4A) The survival rate, (4A) The reproductive rate.

3.4 Effect of Ce2O3/MNCs on the head foot region of B. Alexandrina

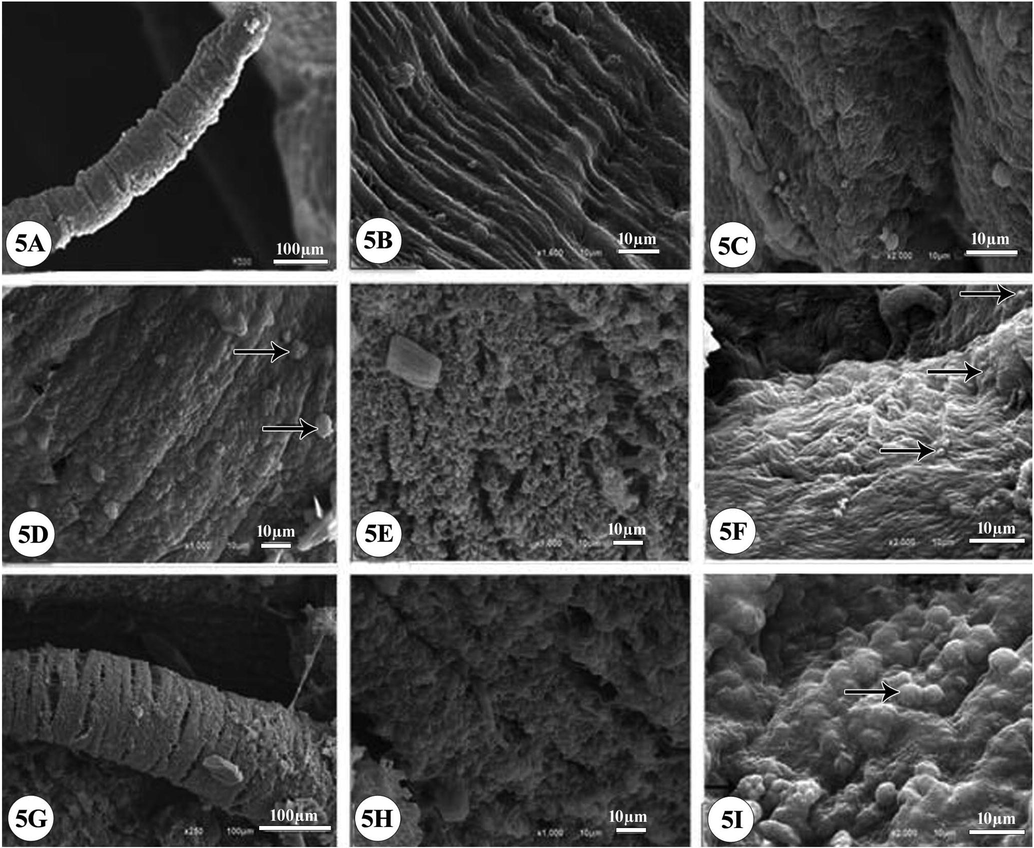

The scanning electron micrographs of the soft part of Biomphalaria alexandrina snails showing the normal tentacles with a smooth surface (Fig. 5A), the smooth tegmental surface of mantle with microvilli and fine spines (Fig. 5B), and foot plantaris with notable surface fold (Fig. 5C). Following the exposure to ¼ of the LC50, the tentacles appeared rough with erosion and damaged cilia (Fig. 5D). Also, the tegmental surface of mantle became rough with mostly complete destroyed microvilli while foot appeared with dense cilia (Fig. 5E, F). Meanwhile after the exposure to ½ of LC50, tentacles appeared rough with erosion (Fig. 5G) and the mantle tegmental architectures was alternated and showed rough surface sometimes with nipples and erosion (Fig. 5H). The foot plantaris folds became flat and the cilia were significantly disappeared (Fig. 5I).

Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of B. alexandrina snails (soft part). (5A) Normal ultrastructure of tentacles with a smooth surface, (5B) the smooth tegmental surface of mantle with conspicuous microvilli and fine spines, (5C) foot plantaris with notable surface fold. After exposure to ¼ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs for 24 h: the micrographs showing limited changes in ultrastructure morphology; (5D) tentacles became rough with erosion (arrows); (5E) the tegmental surface of mantle became rough, most microvilli completely destroyed, (5F) foot with dense cilia (arrows). After exposure to ½ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs for 24 h; (5G) tentacles became rough with erosion (5H) showing alteration of mantle tegmental architectures, rough surface, nipples and erosion, (5I) foot folds became flat, nipples appeared (arrows), the cilia disappeared significantly.

3.5 Ovicidal activity

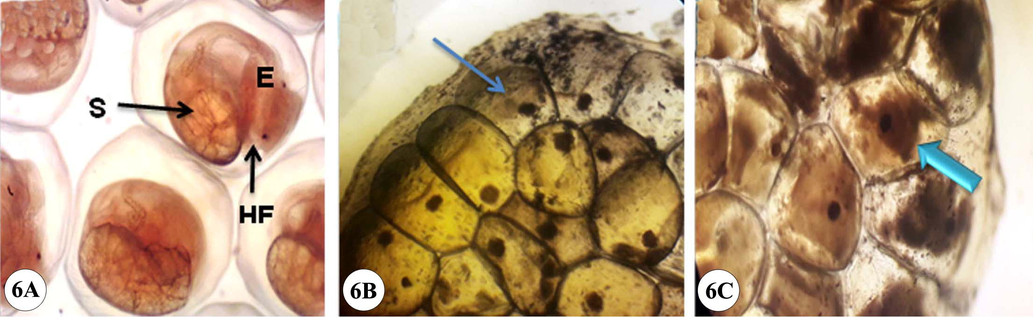

The exposure of B. alexandrina snail’s eggs to the doses of ¼ and ½ of the LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs led to variation in the embryonic development, where some embryos were degenerated and others were died (Fig. 6).

Embryos of B. alexandrina snails (7 days old). (6A) Normal control embryos of seven-days-aged where the snails completely formed (E: eye; HF: head foot; S: shell). (6B) After exposure of the egg mass to ¼ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs while (6C) after exposure to ½ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs for 24 h followed by 24 h of recovery; showing the embryos died (thin arrow) and some degenerated (thick arrow).

3.6 Miracidicidal and cercaricidal activities:

Exposing of S. mansoni miracidae to the dose LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs caused 100% death rate after 210 min compared to 55% in the control group (Table 3). While, 100% death rate of cercariae was achieved after 240 min compared to 60% in the control group.

Conc (mg/L)

mortality % (cumulative) of miracidia and cercariae after the following intervals (min)

30

60

90

120

150

180

210

240

Miracidia

Control

0

0

5

20

40

50

55

65

treated

10

30

60

70

80

90

100

Cercariae

Control

0

0

0

10

20

35

40

60

treated

5

30

35

40

50

80

95

100

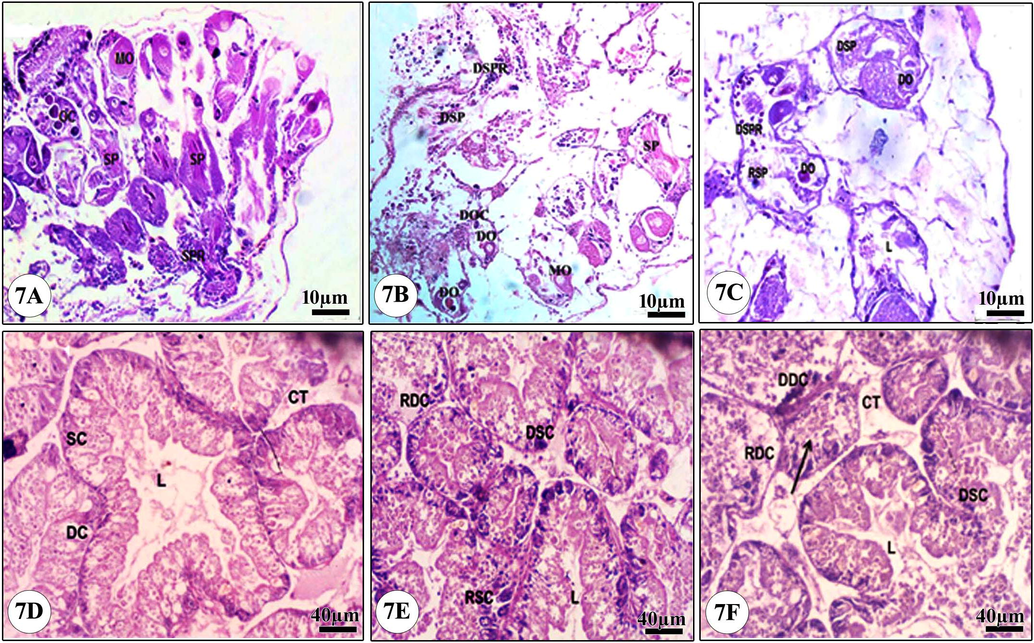

3.7 Histological evaluation

The sections of the control group revealed the hermaphrodite gland containing female oogenic cells with normal oocytes and mature ova and the male reproductive cells with normal spermatocytes and sperms (Fig. 7A). The treatment of snails with a dose of ¼ of the LC50 caused slight disintegration of some oocytes, mature ova, spermatocytes and sperms (Fig. 7B). While, the treatment with a dose of ½ of the LC50, showed significant as the connective tissue was disappeared and replaced by vacuoles with great damage in the gonadal cells in addition to degeneration and destruction in sperms, eggs, spermatocytes, and oocytes (Fig. 7C).

Light micrograph of the hermaphrodite and the digestive glands of B. alexandrina snails. (7A) Normal hermaphrodite gland, (7B) Snails exposed to ¼ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs, (7C) Snails exposed to ½ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs, (7D) Normal digestive gland, (7E) Snails exposed to ¼ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs, (7F) Snails exposed to ½ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs. MO: Mature ovum, OC: Oocytes, SP: Sperms, SPR: Spermatocytes, DO: Degenerated ovum, DSP: Degenerated sperms, DOC: Degenerated oocytes, DSPR: Degenerated spermatocytes. DC: Digestive cells, SC: Secretory cells, L: Lumen, CT: Connective tissue, RDC: Ruptured digestive cells, DDC: Degenerated digestive cells, DSC: Degenerated secretory cells, RSC: Ruptured digestive cells. The arrow indicated that the tubule is totally ruptured.

The digestive gland of the control group showed many tubular glands with one layer of two cells types; secretory cells (SC) and digestive cells (DC) (Fig. 7D). Treatment with ¼ of the LC50 caused some digestive cells rupture and vacuolization in addition to a significant increase in the number of SC (Fig. 7E). While the treatment with ½ of the LC50 led to lumen (L) increase, degeneration and rupture of most of the DC and SC while the tubular glands lost their confirmed shape (Fig. 7F).

4 Discussion

Cerium oxide is one of the important nanomaterials recorded by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (Djanaguiraman et al., 2018). The synthesis of Ce2O3/MNCs bio-composite was carried out through activation, growth and termination stages (Thilagavathi et al., 2015). This newly formed nanoceria possessing large surface area, where, their average particles size ranged from 28.5 to 30 nm as estimated form SEM micrographs and these values were fit to these obtained from XRD data by Debye-Scherrer equation. This novel Ce2O3/MNCs could serve as a new molluscicide.

Therefore, the present study investigated the molluscicidal activities of Ce2O3/MNCs against B. alexandrina. The results showed that Ce2O3/MNCs was toxic to B. alexandrina with LC50 of 314.5 mg/L. Few studies explored the effect of NPs against B. alexandrina as ZnONPs which exhibited molluscicidal effects against B. alexandrina (Fahmy et al., 2014). Also, iron nanoparticles caused significant mortality in B. alexandrina (Khalil et al., 2018). These variations in the molluscicidal effects of the nanoparticles were due to the nature of structure materials and the size differences of the used nanoparticle (Attia et al., 2017). Our results revealed that exposing of B. alexandrina snails to the doses of ¼ and ½ of the LC50 of Ce2O3/MNPs for 24 hrs/ week significantly reduced its survival rate. Similarly, Oliveira-Filho et al. (2019) found that the silver nanoparticles caused adverse effects on the survival and the reproduction rates of Biomphalaria glabrata.

Also, in the present study the concentrations of ¼ and ½ of LC50 of Ce2O3/MNPs were negatively affected the fecundity of the exposed snails and this was associated with significant reduction (p < 0.01) in the reproductive rate (Ro). These adverse effects might be due to the ability of Ce2O3/MNCs to cause oxidative stress (Khorrami et al., 2019) which led to decreasing fertility, delaying in the snail development, and subsequently the death of this snail (Fahmy et al., 2014). Also, these results could be attributed to the harmful effects of Ce2O3/MNCs on the reproductive system of treated snails, hence considerably reduced their oviposition and this was supported by the histological evaluation of the hermaphrodite gland (Seitz et al., 2013; Gallo et al., 2016).

In the present investigation, the exposure of B. alexandrina snails’ eggs to the doses of ¼ and ½ of the LC50 of Ce2O3/MNCs caused embryonic degeneration and embryonic death. The alterations in the embryonic development and the mortalities in embryonated eggs were related to accumulation of particles in egg mass which led to the changes in the nature of hyaline material (ootheca) as suggested by Fahmy et al. (2014). Similarly, Besnaci et al. (2016) found that the application of Fe2O3 nanoparticles on the eggs of Helix aspersa exhibited egg membrane deformation with significant reduction in the hatching rate.

The electron micrographs of B. alexandrina soft parts treated with Ce2O3/MNCs showed alterations in the tentacles and the tegmental architectures. In general, nanomaterials possessed highly adhesive properties to a cell membrane therefore, it affects the membrane structures and its macromolecules (Attia et al., 2017; Rasel et al., 2019). Similarly, the damage in the tegument structure of B. alexandrina due to the exposure to Ce2O3/MNCs could the main cause for its death (Ibrahim and Abdel-Tawab, 2020).

The present results evidenced that Ce2O3/MNCs had cercaricidal and miracidicidal activities. These results agreed with that of Moustafa et al. (2018) who found that silver and gold nanoparticles caused significant increase in the mortality of S. mansoni cercariae and therefore, it could prevent or modulate the infectivity of cercariae in vivo. Also, Shaldoum et al. (2016) found that the infection rate of snails exposed to Cu2O NPs was significantly decreased.

The histological sections of the hermaphrodite gland of B. alexandrina after the exposure to Ce2O3/MNCs showed great damage in the gonadal cells with degeneration of some mature ova, spermatocytes, oocytes and sperms. Also, the connective tissue

was vacuolated and dissolved. Saad et al. (2019) reported similar histological alterations in B. alexandrina treated with Cu2O NPs. The observed reduction in snail egg production due to destruction of hermaphrodite glands which possibly attributed to apoptosis and oxidative damage induced by Ce2O3/MNCs (Omobhude et al., 2017).

Exposing of the digestive gland of B. alexandrina to Ce2O3/MNCs led to significant increase in the number of SC. Meanwhile, DC were ruptured and vacuolated and the tubular glands lost their confirmed shape. Correspondingly, Fahmy and Sayed (2017) reported similar histological alterations in the digestive gland of Coelatura aegyptiaca treatmented with ZnONPs.

4.1 Mechanism of action

The speculated mechanism for bioactivity of Ce2O3/MNCs against B. alexandrina snail was suspected to be as following: Firstly, the exposure of the snails to the testified concentrations of Ce2O3/MNCs caused a noticeable reduction in survival and hatchability rates. Ibrahim and Abdalla, 2017 attributed these effects to the significant increase in the levels of transaminases (ALT and AST) that led to hepatic damage.

Secondly, Ce2O3/MNCs may be uptake into the snail through ingestion and translocate across the gut wall, thus it affects the digestive gland and the hermaphrodite gland which leads to increase in the secretory cells number and loss of the connective tissues in addition to deformed sperms and degenerations of eggs (Cross et al., 2019).

Finally, the exposure to Ce2O3 nano-composite caused damage and alteration in the tegmental architectures of the snail soft parts which induced excessive cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and subsequently leading to noticeable tissue damage due to the oxidative stress (Eom and Choi, 2009; Rogers et al., 2015).

Table 4 showed that the efficiency of our biocatalyst which are higher than the previously reported properties using different biocatalysts from different parts of Moringa.

Plant

Plant part

Snail

Dose

Activity

Reference

Moringa oleifera

Ground seed

Biomphalaria glabrata, Physa marmorata and Melanoides tuberculatus

M. oleifera is active against B. glabrata (LC50:(419mg/l; LC90: (1000mg/l and P. marmorata (LC50: (339mg/l; LC90: (789mg/l) but has no effect against M. tuberculatus.

The seed powder has molluscicidal activity as it caused mortality to the B. glabrata and P. marmorata snail

(Silva et al., 2013)

Aqueous extract of flower

Biomphalaria glabrata

LC50 (2.37mg/ml)

The flower extract has molluscicidal activity as it delayed the development of embyos and caused mortaility to Biomphalaria glabrata adult snails. Also, the embryos generated by snails exposed to the extract were affected

(Rocha-Filho et al., 2015)

Ethanolic extracts of leaf powder

Lymnaea acuminate

96h LC50: (197.59 mg/L)

The leaf powder has molluscicidal activity as it is inhibited secreation of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and acid / alkaline phosphatase (ACP/ ALP) in the nervous tissue of L. acuminate.

(Upadhyay et al., 2013)

5 Conclusion

Herein, we are successfully synthesized Ce2O3/MNCs bio-composite by low cost green synthesis method. The newly synthesized Ce2O3/MNCs bio-composite was characterized by several techniques including XRD, FTIR, HR-TEM, and FE-SEM. The morphological study revealed the formation of uniform agglomeration of spherical particles with average size of 30 nm. The present results showed that the newly synthesized Ce2O3/MNCs has significant lethal effect on B. alexandrina snails and this can affirm its suitability as biodegradable molluscicidal agent. Further field studies are needed to evaluate the effect of Ce2O3/MNCs on the surrounding no target organisms.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Researcher Supporting Project (RSP-2020/3), King Saud University.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- The Impact of three herbicides on biological and histological aspects of Biomphalaria alexandrina, intermediate host of Schistosoma mansoni. Malacologia. 2016;59:197-210.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative stress and genotoxic effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles in freshwater snail Lymnaea luteola L. Aquat. Toxicol.. 2012;124:83-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrophilic nanosilica as a new larvicidal and molluscicidal agent for controlling of major infectious diseases in Egypt. Vet. World. 2017;10:1046-1051.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical molluscicides and schistosomiasis: what we know and what we still need to learn. Vet. Sci.. 2018;5:94.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Embryotoxicity evaluation of iron oxide Fe2O3 on land snails: Helix aspersa. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud.. 2016;4:317-323.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of biogenic nanoparticles for the reduction of 4-nitrophenol and oxidative Laccase-Like reactions. Front. Microbiol.. 2019;10:997.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerium oxide nanoparticles: green synthesis and biological applications. Int. J. Nanomed.. 2017;12:1401-1413.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The fate of cerium oxide nanoparticles in sediments and their routes of uptake in a freshwater worm. Nanotoxicology. 2019;13:894-908.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerium oxide nanoparticles decrease drought induced oxidative damage in sorghum leading to higher photosynthesis and grain yield. ACS Omega. 2018;3:14406-14416.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of low concentrations of sodium pentachlorophenate on the fecundity and egg viability of Bulinus truncatus from Central Iraq. Bull. Endem. Dis.. 1965;7:44-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative stress of CeO2 nanoparticles via p38-Nrf-2 signaling pathway in human bronchial epithelial cell, Beas-2B. Toxicol. Lett.. 2009;187:77-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ecotoxicological effect of sublethal exposure to zinc oxide nanoparticles on freshwater snail Biomphalaria alexandrina. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.. 2014;67:192-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological perturbations of zinc oxide nanoparticles in the Coelatura aegyptiaca mussel. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2017;33:564-575.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finney, D.J., 1971. Probit analsysis, Cambridge University Press, J. Pharm. Sci. 60, 2. https://doi.org/07161417

- Spermiotoxicity of nickel nanoparticles in the marine invertebrate Ciona intestinalis (ascidians) Nanotoxicology. 2016;10:1096-1104.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles based on Trichoderma harzianum: synthesis, characterization, toxicity evaluation and biological activity. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7:44421.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of Moringa oleifera seed aqueous extract on some biological, biochemical, and histological aspects of Biomphalaria alexandrina snails. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int.. 2017;24:28072-28078.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cystoseira barbata marine algae have a molluscicidal activity against Biomphalaria alexandrina snails supported by scanning electron microscopy, hematological and histopathological alterations, and larvicidal activity against the infective stages of Schistosoma mansoni. Biologia. 2020;75:1945-1954.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological impact of oxyfluorfen 24% herbicide on the reproductive system, antioxidant enzymes, and endocrine disruption of Biomphalaria alexandrina (Ehrenberg, 1831) snails. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2019;26:7960-7968.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, L.M.M., Azzam, A.M., M., M., Nigm, A., Taha, H., Soliman, M.I., 2018. In vitro effects of iron nanoparticles on Schistosoma mansoni adult worms and its intermediate host snail. Biomphalaria. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 48, 363–368.

- Antioxidant and toxicity studies of biosynthesized cerium oxide nanoparticles in rats. Int. J. Nanomed.. 2019;14:2915-2926.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Historical perspective: snail control to prevent schistosomiasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.. 2015;9

- [Google Scholar]

- Molluscicidal effect of Achyranthes aspera L. (Amaranthaceae) aqueous extract on adult snails of Biomphalaria pfeifferi and Lymnaea natalensis. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2017;6:133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histological studies on the hermaphrodite gland of Lymnaea caillaudi and Biomphalaria alexandrina upon infection with certain larval trematodes. Egypt. J. Histol.. 1990;13:47-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- The potential effects of silver and gold nanoparticles as molluscicides and cercaricides on Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitol. Res.. 2018;117:3867-3880.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of cercaricidal and miracicidal activity of selected plant extracts against larval stages of Schistosoma mansoni. J. Nat. Sci. Res.. 2016;6:24-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Filho, E.C., de Freitas Muniz, D.H., de Carvalho, E.L., Cáceres-Velez, P.R., Fascineli, M.L., Azevedo, R.B., Grisolia, C.K., 2019. Effects of AgNPs on the snail Biomphalaria glabrata: survival, reproduction and silver accumulation. Toxics 7, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics7010012

- Molluscicidal activities of curcumin-nisin polylactic acid nanoparticle on Biomphalaria pfeifferi. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.. 2017;11

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biomedical applications of Cerium oxide nanoparticles - A Review. Biotechnol Rep. (Amst). 2018;17:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of nanoparticle uptake on the biophysical properties of cell for biomedical engineering applications. Sci. Rep.. 2019;9(9):5859.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Filho, C.A.A., Albuquerque, L.P., Silva, L.R.S., Silva, P.C.B., Coelho, L.C.B.B., Navarro, D.M.A.F., Albuquerque, M.C.P.A., Melo, A.M.M.A., Napoleão, T.H., Pontual, E.V., 2015. Assessment of toxicity of Moringa oleifera flower extract to Biomphalaria glabrata, Schistosoma mansoni and Artemia salina. Chemosphere 132, 188–192.

- Cerium oxide nanoparticle aggregates affect stress response and function in Caenorhabditis elegans. SAGE Open Med.. 2015;3 2050312115575387

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Cystoseira barbata and Dictyota dichotoma-algae on reproduction and protein pattern of Biomphalaria alexandrina snails. Molluscan Res.. 2019;39:82-88.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanoparticle toxicity in Daphnia magna reproduction studies: the importance of test design. Aquat. Toxicol.. 2013;126:163-168.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biomphalaria alexandrina snails as a bio-monitor for water pollution using genotoxic’s effect of cuprous oxide nanoparticles and copper sulphate. Middle East J. Appl. Sci.. 2016;6:189-197.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molluscicidal activity of Moringa oleiferaon on Biomphalaria glabrata: integrated dynamics to the control of the snail host of Schistosoma mansoni. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn.. 2013;23:848-850.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Green” synthesis of metals and their oxide nanoparticles: applications for environmental remediation. J. Nanobiotechnol.. 2018;16:84.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary phytochemical screening of different solvent mediated medicinal plant extracts evaluated. Int. Res. J. Pharm.. 2015;6:10-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of molluscicidal component of Moringa oleifera leaf and Momordica charantia fruits and their modes of action in snail Lymnaea acuminata. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 2013;55:251-259.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biogenic synthesis of Pd-based nanoparticles with enhanced catalytic activity. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.. 2018;1:1467-1475.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanomaterials for the removal of heavy metals from wastewater. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:424.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]