Translate this page into:

GCMS fingerprinting, in vitro pharmacological activities, and in vivo anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effect of selected edible herbs from Kashmir valley

⁎Corresponding authors. smarazi@ksu.edu.sa (Suhail Razak), tayyaba_sona@yahoo.com (Tayyaba Afsar),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

The people of Kashmir customarily practice traditional medicines for curing various ailments. 3 nutritious herbs; Melissa officinalis L (Lamiaceae, MO), Taraxacum officinale L (Compositae, TO), and Urtica dioica L (Urticaceae, UD) were selected based on their ingestion as a folklore remedy for treating various illness, including infections, inflammation, and cancer. We aimed to scientifically validate their indigenous usage. Plant extracts were prepared by extraction in 95% methanol and subjected to qualitative phytochemical screening, total phenolic (TPC), flavonoid content (TFC), and Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS). In vitro, antioxidant and antiproliferative activities were determined. For in vivo study; 56 Wister rats were randomly assorted into 8 groups. Rats in the control group received saline, toxicity group received Acetaminophen/paracetamol (APAP, 2 g/kg b.w) orally for 7 days. Treatment groups received 300 mg/kg of MO, TO, or UD, respectively for 7 days after APAP (2 g/kg b.w) administration. Serum inflammation markers, antioxidant parameters, and histopathology were investigated. The GC–MS of methanol extracts indicated 16 compounds in MO (21.6% 1-nitro-β-d-arabinofuranos, as major compound), 19 compounds in TO (30.06% rutin, as major compound) and 15 compounds in UD (29.86% saponin, as major compound). TO exhibited more significant antiradical capacity in DPPH assay (IC50 29.6 ± 1.12 µg/mL) and antioxidant activity in CUPRAC assay (889.34 ± 5.65 μM Trolox/g DW of extract) compared to MO (657.77 ± 5.21) and UD (534.45 ± 4.56). MO, TO and UD exhibited potent anti-proliferative potency against HT 29 and HCT 116 cancer cells, while no cytotoxicity against normal Vero cell lines. MO, TO, and UD ameliorated (p < 0.001) APAP-induced hepatotoxicity by improving elevated ALT, AST, and ALP levels and significantly (p < 0.001) decreasing TNF-α and IL-6 levels in serum. Histological examinations confirmed the biochemical findings. The present study confirmed the scientific basis for the application of (selected) medicinal herbs (studied). Plant extracts revealed antioxidant and hepatoprotective potential against APAP-induced liver injury. Further investigations to understand the mechanism of action and use in clinical trials is recommended.

Keywords

GC–MS

Nutritious herbs

Melissa officinalis

Taraxacum officinale

Urtica dioica

Anticancer

Antioxidant

Hepatoprotective

- GCMS

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- DPPH

2, 2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- CUPRAC

Cupric reducing antioxidant capacity

- CFU

Colony-forming unit

- APAP

Acetaminophen/paracetamol

- LFTs

Liver function tests

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- GSH

Glutathione

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- POD

Peroxidase

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- LPO

Lipid peroxidation

- DDMP

2, 3-dihydro-2, 5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one

- PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Jammu and Kashmir Himalaya’s often referred to as Terrestrial Paradise on Earth, is situated at the Northwestern tip of the Himalayan biodiversity hotspot. The valuable indigenous knowledge, when accompanied and validated by the most modern scientific insights, can propose novel drug leads (Malik et al., 2011b). For the current investigation, we have selected the three edible herbs. These herbs were chosen based on recorded ethnobotanical information, confirmation for their sustained usage, and indigenous accessibility.

Melissa officinalis L. (Lamiaceae) is a perennial edible herb commonly called lemon balm. In India; lemon balm is cultivated in Jammu and Kashmir, Uttrakhand, and some parts of South India (Verma et al., 2015). MO is traditionally used as an antispasmodic, anti-insomnia tonic, carminative, painkiller, for digestion, antidepressant, memory booster, antibacterial, antiviral (Verma et al., 2015). MO essential oil possesses antimicrobial, anticancer, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects (Moacă et al., 2018). Citronellal, citral, geranial, terpinene, rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, several flavonoids (luteolin-7-O-glucoside, isoquercitrin, apigenin-7-O-glucoside, and rhamnocitrin), methyl carnosoate, rosmarinic acid, ferulic acid, 2 (3, 4-dihydroxyphenyl), and hydroxycinnamic acid are main metabolites identified in MO oil.

Taraxacum officinale L. (Compositae) commonly known as Dandelion (Local Kashmiri name: Handh) is a perennial edible herb. In Jammu and Kashmir, it is commonly distributed throughout Gurez, Tilel, Dachigam, Dubjan, Sonamarag, and Gulmarg. TO is traditionally used in the cure of various problems i.e., for the treatment of chronic cough, asthma, infection, acidity, urinary disorders, cirrhosis, jaundice, dyspepsia with constipation, and heart weakness, gout, eczema, blood purifier and specially used by women's after childbirth to prevent inflammation (Choi et al., 2010). The leaves and roots possess antitumor, antioxidant, and hypolipidemic activities. The roots contain carbohydrates, sesquiterpene lactones, carotenoids (lutein), fatty acids (myristic), flavonoids (apigenin and luteolin), and triterpenes while leaves possess cichoriin, Taraxalisin, coumarins, and aesculin (Nahid et al., 2008).

Urtica dioica L. (Urticaceae) commonly known as stinging nettle (Local Kashmiri name: Soyi) is an abundant herb that grows on moist and fertile soil. In folk medicine, it is used as a remedy for paralytic limbs or flailing arthritic, rheumatism. (Malik et al., 2011a). UD is infrequently domesticated because of its sting, however, the species is still prevalent as medicines and food in under developing countries. UD is a worthy source of caffeic acid analogs, flavonoids, and phenylpropanoids (Adhikari et al., 2016). Further work should be done to learn the medicinal value of these three edible herbs from Kashmir cultivars.

We aim to investigate the antioxidant, anticancer, hepatoprotective, and anti-inflammatory potential of three selected herbs. Furthermore, the phytochemical analysis was validated by GCMS analysis.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Plant collection

Melissa officinalis L. (MO; leaves, and stem), Urtica dioica L. (UD; leaves, and stem) and Taraxacum officinale L. (TO; leaves, stem, and roots) were collected in July from Qazigund area, Anantnag District, Jammu, and Kashmir. Plant specimens were identified by Raouf Ahmad Mir (Head Product Development, Globils Agri and Food Enterprises, Lassipora, Pulwama, J&K) and voucher specimens (#0235601, #0235602 and 0235603) were deposited at the herbarium of Globils Agri and Food Enterprises (Lassipora, Pulwama, J&K, India).

2.2 Ethics statement

No particular authorizations were required for the collection of plants as the areas were not in private-possession or secure in any way and the field studies did not encompass endangered or protected species.

2.3 Description of plant collection area

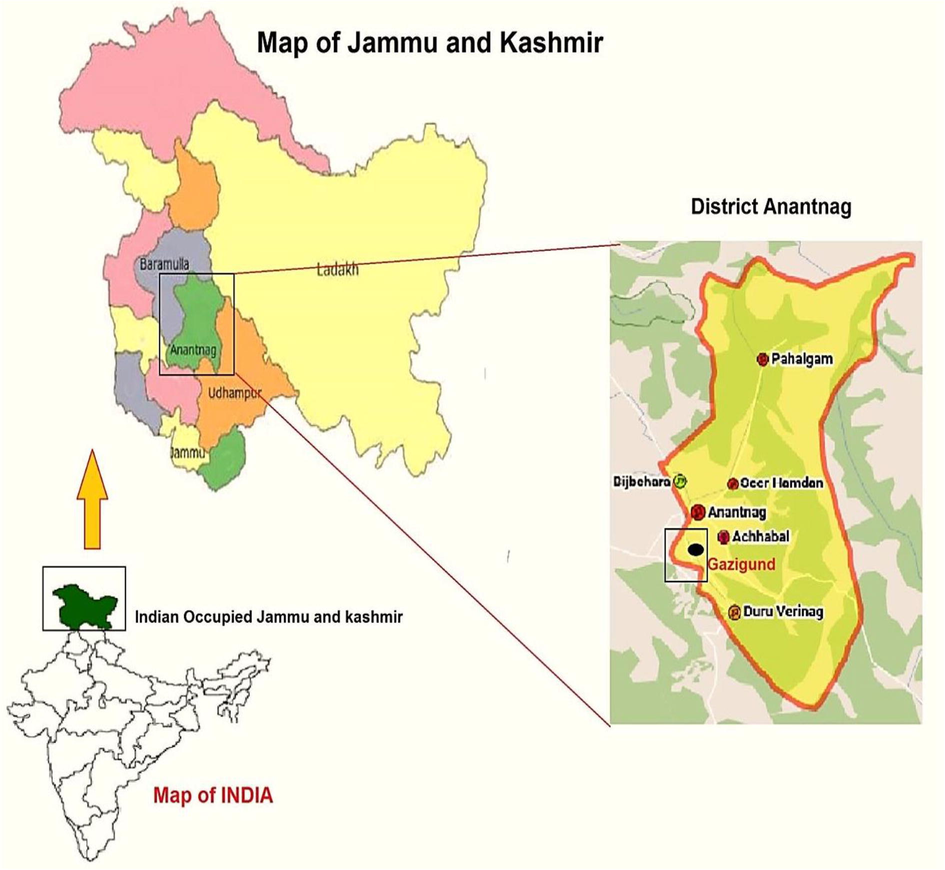

Anantnag district is in the southern sector of Jhelum Valley, geographically lies between 33°-20ʹ to 34°-15ʹ north latitude and 74°–30ʹ to 75°–35ʹ east longitude. It is the third most populous district of Jammu and Kashmir. It comprises of thick forests and mountains. The weather is mild cold in summer also. Map of the study area is shown in Fig. 1.

Map of study area. Maps were downloaded from www.mapsofindia.com and modified.

2.4 Plant extracts preparation

Herbs were dried in the shade for 10 days and powdered with a blender. Each plant powder (5 g) was added to 100 mL methanol (95%) and placed in a water bath at 37 °C for 3 h. The mixture was extracted twice with 100 mL of methanol for 72 h at room temperature and filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The filtrates were concentrated in vacuo using a rotary evaporator (Buchi, R114, Switzerland).

2.5 Qualitative and quantitative phytochemical screening

The extracts were subjected to qualitative phytochemical analysis by the well-defined methods for the detection of flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, terpenoids, tannins, cardiac glycoside, reducing sugars, pholobatannins, coumarins, and anthraquinones. Total phenolic content was measured using Folin-Ciocalteu reagents. An aqueous solution of gallic acid (10–500 mg/L concentrations) was used for calibration. The results were represented as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/g sample. The total flavonoid content was checked according to the colorimetric assay (Afsar et al., 2016). Aqueous solutions of known rutin concentrations in the range of 50–100 mg/L were used for calibration and the results were expressed as mg rutin equivalents (REQ)/g sample.

2.6 Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS)

To investigate the chemical fingerprinting of the different crude extracts, GC/MS analysis was performed using Thermo GC -Trace Ultra version 5.0, apparatus combined with Thermo MS DSQ II mass spectrometer. The mixtures were partitioned on a ZB 5-MS capillary regular non-polar column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm FILM) to purify the samples. The column temperature was set at 70 °C for 2 min, 70–260 °C at 6 °C/min, and as a final point held for 10 min at 260 °C. The particle-free diluted sample was introduced in splitless mode (split-flow: 10 mL/min, splitless time: 1 min). The carrier gas (helium) was employed at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min and 1 μL sample was injected. The relative percentages of crude extract constituents were quantified as peak area normalization. The mass spectral scan range was set in full scan mode from 50 to 650 (m/z). The compounds were identified by comparing their retention indices with those of authentic samples deposited on the Wiley9 and main lab computer library search program; built up using authentic compounds (Casuga et al., 2016).

2.7 Determination of antioxidant activity

2.7.1 Sample preparation

The stock solution of each extract was prepared in methanol (95%) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL and diluted to make the successive dilutions (0–250 µg/mL).

2.7.1.1 DPPH assay

The DPPH assay was done by the previously described protocol (Afsar et al., 2016). The absorbance was recorded using a UV-1601 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at 517 nm. The percentage of inhibition was assessed as follow:

As a standard reference compound ascorbic acid was employed.

2.7.1.2 Reducing capacity measurement using CUPRAC technique

The cupric ion reducing the antioxidant ability of all extracts was evaluated following the previously described scheme (Al-Rimawi et al., 2016). The absorbance was noted at 450 nm compared to the reagent blank. A Standard curve was set via various doses of Trolox.

The results were shown as:

2.8 Anti-proliferative activity

2.8.1 Cell lines and culture conditions

Human colorectal cancer cell lines HCT 116 and HT 29 (ATCC® CCL-247™ and ATCC® HTB-38™ respectively) and purchased from American Type Culture Collection (MD, USA). A Vero (CCL-81™, normal kidney cells) cell line was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). HCT 116 and HT 29 were grown in a CO2 (5%) atmosphere at 37 °C in medium (DMEM medium 1640 (GIBCO), 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin). MO, TO and UD extract samples suspended in DMSO were tested for anti-proliferative activity against both cell lines. Cells were grown to get 70% confluence and treated with different concentrations (0–50 µg) of each extracted sample for 48 h. The dilution of DMSO applied for each treatment was 0.1% (V/V).

2.8.1.1 Measurement of Anti-proliferative activity

10 × 103 cells/well were grown in 1 mL of culture medium comprising 0–250 µg dilution of each sample in 96-well plate. Cells were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C, 200 µL of 3–4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (5–7 mg/mL PBS) was added to each well and incubated for 2 h and 200 µL of DMSO was added and spun (1800×g for 5 min at 4 °C). The absorbance was taken at 540 nm on a microplate reader (Elx 800). Cell viability in each tested sample was calculated by the following formula:

Blank is the absorbance of only cell culture media without the cancer cells.

IC50 values were calculated using Graph pad prism 5

2.9 Animal model of hepatotoxicity

Adult male Wister rats, weighing 200 – 220 g, were kept under standard laboratory conditions on a 12-h light/dark cycle at 25° C ± 2° C. The animals had free access to standard rat pellet diet with water ad libitum. All animals were kept following the recommendations of the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH publications no. 80–23; 1996).

2.9.1 Acute toxicity testing

The acute toxicity examination was led in line with the guideline 425 of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for the analysis of substances for acute oral toxicity. Male Wister rats (n = 6) were treated with different doses (50, 250, 500, 1000, 2000, and 3000 mg/kg, p.o.) of MO, TO and UD, while the control group received distilled water. Animals were detected constantly for 2 h for comportment, and autonomic profiles and later 24 h and 72 h for any fatality (Afsar and Razak, 2019).

2.9.2 In vivo Experimental plan

56 male Wister rats were randomly allocated into 8 groups (n = 7). The group I received saline. Group II, III, and IV were treated orally for 7 days with 300 mg/kg dose of MO, TO and UD respectively. In Group V received Acetaminophen/paracetamol (APAP) (2 g/kg b.w) for 7 days orally (Mishra et al., 2015). Group VI, VII, and VIII were co-treated with APAP + MO (300 mg/kg b.w, oral), APAP (2 g/kg b.w) + TO (300 mg/kg b.w, oral) and APAP (2 g/kg b.w) + UD (300 mg/kg b.w, oral) respectively for 7 days.

24 h after the last treatment, all animals were weighed and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Trunk blood was taken and centrifuged at 500×g for 15 min at 4 °C to obtain serum and kept on −80 °C for further analysis. The liver was removed; one-half was preserved in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further biochemical analysis while the remaining half was processed for histology.

2.9.3 Liver function tests (LFTs) in serum

Serum examination of various liver function biomarkers such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was estimated by using standard AMP diagnostic kits (Stattogger Strasse 31b 8045 Graz, Austria).

2.9.4 Determination of serum TNF-α and IL-6

Concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 in serum were determined using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer manual (R&D systems).

2.9.5 Estimation of tissue protein content

Total soluble protein content within the tissue samples was estimated using a previously established protocol (Afsar and Razak, 2019).

2.9.6 Assessment of biochemical parameters

GSH, SOD, and MDA levels in liver tissues were tested following previously described protocols (Afsar and Razak, 2019).

2.9.7 Histopathological examination by light microscopy

Liver tissues from the respective groups were preserved in buffered formalin. After dehydration tissue samples were secured in paraffin to make blocks for microtomy. Tissues were sectioned 4–5 µm with a microtome and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) and studied under a light microscope (DIALUX 20 EB) at 40X.

2.9.8 Statistical tests

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate. Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way and two-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis using Graphpad Prism software. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Qualitative and quantitative phytochemical screening

Table 1 shows the qualitative and quantitative phytochemical analysis of methanol extract of MO, TO, and UD. Qualitative phytochemical screening indicated various polar and nonpolar components in all extracts. The chemical composition of MO oils has done previously (Pirbalouti et al., 2019); however, this is the first report on the methanol crude extract collected from Kashmir. Phenolic and flavonoid constituent function as antioxidants and play a role in combating cancer, infection, and vast degenerative infirmities (Afsar et al., 2016). The quantity of phenolic and flavonoid content in MO, TO, and UD methanol extracts were calculated from the standard calibration curve of gallic acid (R2 = 0.93) and rutin (R2 = 0.92) respectively. TO showed the highest content of TPC and TFC, followed by MO and UD (Table 1). The total phenolic contents of TO extract determined in the current study were noted to be higher than calculated from methanol extract of Brazilian species (Colle et al., 2012). This might be linked to variation in agro-climatic conditions, maturity at harvest as well as a difference in extraction technique and polarity of extracting solvent. A negative sign (−) indicates absence, positive sign (+) indicates presence, N/A indicates not applicable for the specific testing. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Data analyzed by One-way ANOVA using Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test. Asterisks *, **, *** represent significance at p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001 from MO, + represent significance at p < 0.01 from TO and #, ### represent significance at p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001 from ASC standard compound. MO: Melissa officinalis, TO: Taraxacum officinale and UD: Urtica dioica.

Tests

Samples

Melissa officinalis (MO)

Taraxacum officinale (TO)

Urtica dioica (UD)

Ascorbic acid (ASC)

Qualitative phytochemical screening

Tannins

+

+

+

N/A

Steroids

+

+

+

N/A

Saponins

+

+

+

N/A

Alkaloids

+

+

+

N/A

Flavonoids

+

+

+

N/A

Coumarins

+

+

–

N/A

Terpenoids

+

+

+

N/A

Pholobatanins

+

+

–

N/A

Reducing sugars

+

+

+

N/A

Anthraquinones

+

–

–

N/A

Cardiac Glycosides

+

+

+

N/A

Quantitative phytochemical screening

TPC (mg gallic acid equivalent/g dry sample

151.6 ± 1.21

185.3 ± 1.15**

99.5 ± 1.98***,##

N/A

TFC (mg rutin equivalent/g dry sample

117 ± 3.52

149 ± 1.32**

84 ± 1.04***,##

N/A

Antioxidant activity

DPPH IC50 (µgml)

43.8 ± 1.22

29.6 ± 1.12***

76.3 ± 1.92***,+++,###

25.4 ± 1.51

CUPRAC (μmol Trolox/g DW of extract)

657.77 ± 5.21

889.34 ± 5.65***

534.45 ± 4.56+++,###

3.2 Compound fingerprinting by GCMS

3.2.1 Chemical profiling of M. officinalis

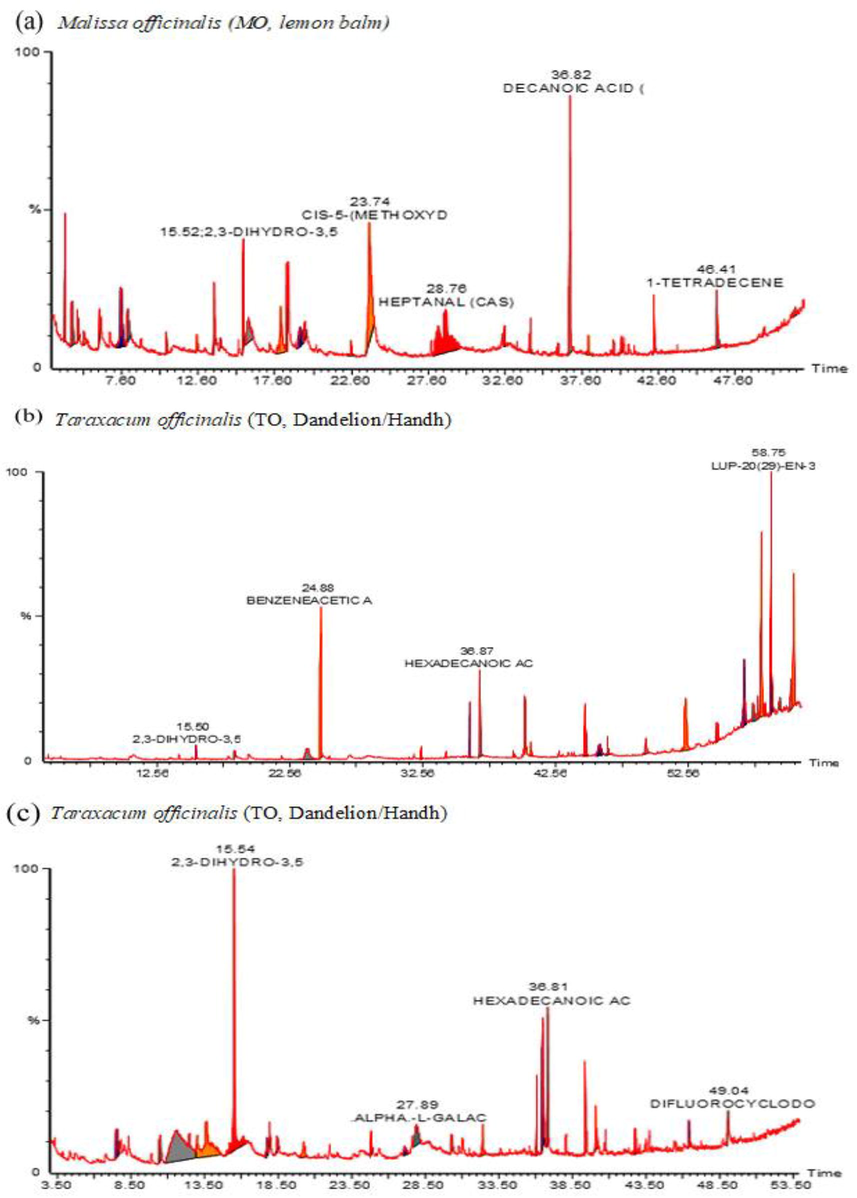

GCMS chromatogram detected the presence of 16 constituents in the methanol extract of MO harvested in Kashmir (Fig. 2a, Table 2), representing 91.2% of the composition of MO. Dominant compounds on the basis of % peak area and bioactivity were 1-nitro-β-d-arabino-furanos (21.57%), 3-hydroxy-2 methyl-4 h-pyran-4-one (maltol, 11.54%), methyl (E)-3-acetoxy-4-nitro-2-butenoate (9.71%), 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4 h-pyran-4-one (DDMP, 8.54%), decanoic acid (7.21%), dl-glyceraldehyde dimer (6.08%), 2-furan-carboxaldehyde (5.9%), 4-methyl-morpholine (2.93%). Furan and pyran derivatives are major compounds identified in MO by GCMS possess anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial potentials (Chai et al., 2013). while DDMP is a saponin with proven antioxidant and antitumor potentials (Čechovská et al., 2011). The presence of bioactive metabolites in MO might be attributed to the therapeutic actions of MO.

GCMS fingerprinting of crude methanol extract of Malissa officinalis (MO, lemon balm), Taraxacum officinalis (TO, Dandelion/Handh), and Urtica dioica (UD, Nettle/soyi). GCMS analysis detected 16 compounds in MO, 19 compounds in TO, and 15 compounds in UD. Compounds were identified based on % peak area and retention time.

Peak

Compounds

RT

Area

% Area

Compound class/activity

1

METHYL (E)-3-ACETOXY-4-NITRO-2-BUTENOATE

7.55

103,097

9.71

acrylate ester

2

DL-GLYCERALDEHYDE DIMER

7.99

64,618

6.08

Carbohydrate (preservative)

3

2,4-DIHYDROXY-2,5-DIMETHYL-3(2H)-FURAN-3-ONE

10.52

15,355

1.450

Furan (Aroma compound/antioxidant/ anticancer)

4

4-METHYL-MORPHOLINE

12.51

31,164

2.930

Tertiary amine (Pharmaceutical industry/ Antibacterial, anticancer)

5

3-HYDROXY-2-METHYL-4H-PYRAN-4-ONE

13.63

122,546

11.54

Phenol/Maltol (antioxidant, anticancer (Wang, Jenner et al. 2007)

6

CYCLOBUTANOL

14.04

48,513

4.570

Cyclic alcohol

7

2,3-DIHYDRO-3,5-DIHYDROXY-6-METHYL-4H-PYRAN-4-ONE

15.52

89,778

8.450

(DDMP) (anticancer, antioxidant (Čechovská et al., 2011)).

8

2-FURANCARBOXALDEHYDE

17.96

63,426

5.970

Aldehyde/Furfural (Major flavor component, antimicrobial (Chai et al., 2013)

9

1-NITRO-.BETA.-D-ARABINOFURANOS

18.41

229,129

21.570

heterocyclic compounds Nucleoside (antineoplastic)

10

2,3-DIHYDROXY-PROPANAL

19.22

54,504

5.130

Glyceraldehyde metabolite

11

HEPTANAL

28.76

19,636

1.85

Alkyl aldehyde (flavoring agent)

12

DECANOIC ACID

36.82

76,636

7.210

Fatty acid /Capric acid Flavoring agent, anticancer activity on cultured human colorectal, skin and breast cancer (Narayanan, Baskaran et al. 2015)

13

ISOPROPYL MYRISTATE

38.04

5897

0.560

Ester of isopropyl alcohol and myristic acid

14

EICOSYL ACETATE

40.24

9443

0.890

Fatty ester/pheromone

15

BETA.-H-PREGNANE

42.31

18,559

1.750

steroid

16

TETRADECENE

46.41

23,985

2.260

Acyclic olefins.

3.2.2 Chemical profiling of T. officinalis

GCMS analysis detected 19 compounds in the methanol extract of TO harvested in Kashmir (Fig. 2b, Table 3) representing 99.99% of the TO compositions. Dominant active compounds on the basis of % peak area and retention time were hydroxy-benzeneacetic acid (rutin metabolite, 30.060%), β-amyrin (10.790%), eicosane (8.580%), Lup-20(29)-en-3-ol (7.320%), hentriacontane (6.54%), 3-methyl-2-pentanone (6.24%), hexadecanoic acid (3.160%), methyl ester of hexadecanoic acid (2.78%), lupeol (2.99%), and tritetracontane (2.10%). Active metabolites detected in TO belongs to phenols, terpenes, fatty acids, and alkanes classes. The identification of triterpenes in TO is scientific validation of its use in inflammatory conditions, especially after pregnancy because the identified compounds have potent anti-inflammatory activity. The antioxidant action of TO might be attributed to amyrin isomers. β-amyrins have anti-apoptotic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and hepatoprotective effects (Ghosh et al., 2015). The bioactive fatty acids identified in TO are palmitic acid (methyl ester of hexadecanoic acid 2.780% and hexadecanoic acid 3.160%). Palmitic acid possesses antimicrobial, antitumor, and antioxidant activities (Harada et al., 2002; Pinto et al., 2017). Lupeol has diverse therapeutic potentials including antioxidant, anticancer, hepatoprotective, chemo-preventive, and anti-inflammatory (Wal et al. 2011).

Peak

Compounds

RT

Area

Area %

Compound class/activity

1

2,3-DIHYDRO-3,5-DIHYDROXY-6-METHYL

4-H-PYRAN-4-ONE15.50

25,150

0.440

Saponin/DDMP (Antioxidant, anticancer (Čechovská et al., 2011))

2

3-HYDROXY-HEXANOIC ACID

18.39

137,126

2.410

Fatty acid

3

3-METHYL-2-PENTANONE

23.90

354,832

6.240

Aliphatic ketone (flavoring agent)

4

HYDROXY-BENZENEACETIC ACID

24.88

1,710,578

30.060

Phenol/Rutin metabolite (antioxidant anticancer against colon cancer (Amić et al., 2016)

5

TETRADECANOIC ACID

32.44

25,427

0.450

Fatty acid/Myristic acid (anticancer, Reno-protective)

6

METHYL ESTER OF HEXADECANOIC ACID

36.09

158,163

2.780

Fatty acid/palmitic acid methyl ester/metabolite (antimicrobial, antitumor, antioxidant (Harada et al., 2002, Pinto et al., 2017)

7

HEXADECANOIC ACID

36.87

179,928

3.160

Fatty acid /palmitic acid (antimicrobial, antitumor ,antioxidant (Harada et al., 2002, Pinto et al., 2017))

8

DECANENITRILE

40.26

124,901

2.190

Nitrile (fragrance)

9

4-ETHYL-2,6-DIMETHTHYL-4-HEPTANOL

40.69

18,395

0.320

Alcohol (Sweat aroma)

10

HENTRIACONTANE

44.79

372,386

6.540

Alkane (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticancer (Khajuria, Gupta et al. 2017)

11

2-HYDROXY-1-HEXADECANOIC ACID

46.47

37,435

0.660

Fatty acid

12

TRITETRACONTANE

49.33

119,447

2.100

Alkyl (Anti-inflammatory)

13

NONACOSANE

52.31

45,389

7.980

Alkane/ plant metabolite (Pheromone)

14

2-OCTYLDODECAN-1-OL

54.70

157,603

2.770

Fatty Alcohol (emollient)

15

EICOSANE

56.71

488,368

8.580

Alkanes (plant metabolite, antioxidant, Anti-tumor activity against the human gastric SGC-7901 cell line (Sivasubramanian and Brindha 2013)

16

COPROSTAN-16.BETA.-OL

57.74

126,612

2.220

Cholesterol

17

BETA.-AMYRIN

58.03

614,141

10.790

Pentacyclic triterpenoid (Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant (Ghosh et al., 2015))

18

LUP-20(29)-EN-3-OL

58.76

416,300

7.320

Triterpene (antioxidant, anticancer, hepatoprotective, antibacterial, chemo- preventive, anti-inflammatory (Wal, Wal et al. 2011))

19

LUPEOL

60.44

170,112

2.990

Triterpene (Wal, Wal et al. 2011)

3.2.3 Chemical profiling of U. dioica

GCMS analysis detected 15 compounds in the methanol extract of UD harvested in Kashmir (Fig. 2c, Table 4) representing 95.38% of UD chemical composition. Dominant active compounds identified on the basis of % peak area and bioactivity were 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4 h-pyran-4-one (29.860%), β-ketoglutaric acid (15.910%), N-(phenethyl) phenylacetamide (15.260%), 3-amino-2-oxazolidinone (7.530%), α.-l-galactopyranoside (5.380%), Ketoglutaric benzenepropanoic acid/hydrocinnamic acid (4.570%), hexadecanoic acid (4.250%), and 9, 12-octadecadienoic acid (2.020%). In UD, the major antioxidant and anti-mutagenic components identified are 2, 3-dihydro-3, and 5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4 h-pyran-4-one (DDMP). The previous report revealed DDMP as a major antioxidant compound in prunes and plums (Čechovská et al., 2011). α-ketoglutarate is the main component of the Krebs cycle that plays a role in protein synthesis, bone development and not only extends lifespan but also delays age-related diseases, indicating its role in the prevention and treatment of aging and age-related diseases (Wu et al., 2016). Linolenic acids are essential long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that decrease chronic degenerative and inflammatory diseases (Saha and Ghosh 2012). The therapeutic potential of combine fatty acid composition may probably contribute to the health benefits of UD.

Peak

Compounds

RT

Area

Area %

Compound class/activity

1

B-KETOGLUTARIC ACID

7.57

384,553

15.910

Carboxylic acid (antibacterial)

2

2,3-DIHYDRO-3,5-DIHYDROXY-6-METHYL-4H-PYRAN-4-ONE

15.54

721,644

29.860

Saponin/DDMP (antioxidant, Anti- proliferative, pro-apoptotic against colon cancer, antioxidant (Čechovská et al., 2011)

3

HEXANAMIDE

17.76

33,834

1.400

Amide

4

3-AMINO-2-OXAZOLIDINONE

18.45

182,010

7.530

Metabolite of Furazolidone and Nitrofuran, (Antibacterial , antibiotic (Cooper, Elliott et al. 2004).

5

N-METHYL-3-ETHOXYAMPHETAMINE

20.25

14,373

0.590

alkaloid

6

BENZENEPROPANOIC ACID

24.82

110,513

4.570

Carboxylic acid / hydrocinnamic acid (used for flavoring, a preservative to maintain the original aroma quality of frozen foods, antioxidant, antimicrobial (Sova 2012).

7

ALPHA.-L-GALACTOPYRANOSIDE

27.86

129,912

5.380

Carbohydrate (an energy source for the body)

8

DECANOIC ACID

32.40

21,282

0.880

Fatty acid

9

PENTADECANOIC ACID

36.06

94,085

3.890

Fatty acid/milk fat

10

N-(PHENETHYL) PHENYLACETAMIDE

36.46

368,724

15.260

Amide(anticancer, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antibacterial (Rani, Pal et al. 2014))

11

HEXADECANOIC ACID

36.81

102,593

4.250

Fatty acid/ palmatic acid (Harada et al., 2002; Pinto et al., 2017)

12

9,12-OCTADECADIENOIC ACID

39.34

48,857

2.020

Fatty acid/linoliec acid (antioxidant, antitumour (Saha and Ghosh 2012))

13

D6-DODECENE-1-OL

40.05

55,273

2.290

Acyclic Alkenes

14

2-HEXYLALLYL ALCOHOL

42.75

35,179

1.460

Alcohol

15

HEXADECANOIC ACID

46.29

2080

0.090

Fatty acid

3.3 Determination of antioxidant activity

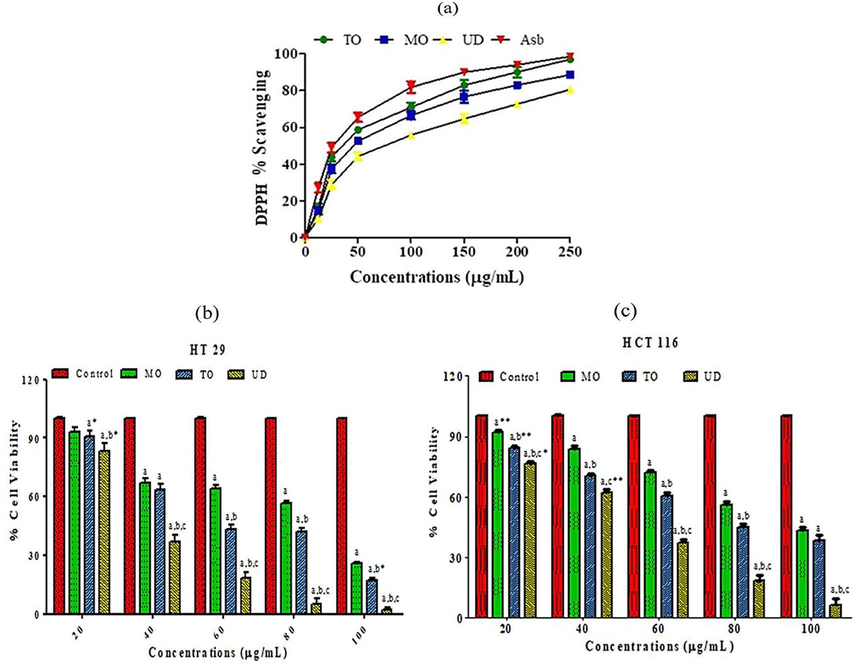

The free radical scavenging potential of MO, TO and UD extracts against DPPH radical in comparison with standard antioxidants ascorbic acid is shown in Fig. 3a. The IC50 values of all tested extracts and standard antioxidants are shown in Table 1. The overall activity followed the sequence; ascorbic acid > TO > MO > UD. The observed anti-radical activity would be attributed to the highest amount of phenolic and flavonoids in these herbal extracts. Correlation analysis indicated that the DPPH radical quenching activity of extracts showed good correlation with TPC (R2 = 0.9879) and TFC (R2 = 0.8477).

(a) Dose-dependent scavenging activity of methanol extracts of 3 edible herbs (MO, TO and UD). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). GA: Ascorbic acid used as a standard reference compound. (b) The anti-proliferative potential of MO, TO and UD against HT 29 cells. (c) The anti-proliferative potential of MO, TO and UD against HCT 116 cells. Cells viability percentage measured by MTT assay. Values expressed as mean ± SEM. Alphabets show significance from the control group at p < 0.0001, “b” indicates significance from MO treated group at p < 0.0001, and “c” indicates significance from TO treated group at p < 0.0001. Asterisks *, ** shows significance at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001. (Two-way ANOVA accompanied by Bonferroni posttests). MO: Melissa officinalis, TO: Taraxacum officinale and UD: Urtica dioica.

The CUPRAC absorbance of the incubation solution due to the reduction of Cu (II)-neocuproine reagent decreased in the presence of polyphenolics. The extracts (250 μg/mL) exhibited good CUPRAC total capacities. The reducing potential of studied herbal extracts was in the order of TO > MO > UD (Table 1). Reducing the potential of the methanol extracts of tested herbal extracts showed a good correlation with total phenolic (R2 = 0.979) and flavonoid content (R2 = 0.8977). The Significant antioxidant potential of the individual herb was observed by other researchers while examining the antioxidant activity of TO flower extract (Colle et al., 2012), ethanol, and water extract of MO leaves (Koksal et al., 2011) and protein fractions from aerial parts of UD (Di Sotto et al., 2015). Secondary metabolites have been identified in all extracts by GCMS that have proven antioxidant activities.

3.4 Specific anti-proliferative activity against cancer cells

The result of the MTT assay revealed that all extracts inhibited colon cell proliferation in a dose-dependent response; maximum cell inhibition was observed at 250 µg/mL against both cell lines (Fig. 3b and c). UD treatment was more effective against both cell lines compared to MO and TO, with IC50 values found to be 35.30 ± 1.86 µg/mL for HT 29 cell line, and 49.80 ± 1.85 µg/mL for HCT 116 cell line (Table 5). All tested extracts did not show growth inhibitory effects against normal Vero cells up to 250 μg/mL. The anticancer potential was in the order of UD > TO > MO. In a previous investigation, 50% ethanolic extracts of MO showed significant inhibition of cell proliferation against HTC116 cells after 72 h of treatment, reducing cell proliferation to values close to 40% at 5 μg/mL dose (Encalada et al., 2011). The furans and pyran metabolites seem to be the bioactive, involved in inducing anticancer activity in MO. UD has been used traditionally for cancer treatment and this is the first scientific validation of the anti-proliferative potential of UD against colon cancer cells. In TO, the major compound detected by GCMS examination was Rutin metabolite (30.06%) besides several other constituents with potent anticancer and anti-inflammatory potential (Amić et al., 2016). The major anticancer metabolite in UD seems to be saponin (DDMP: 29.86%). DDMP significantly suppresses cancer growth in colon cell lines (Salyer 2011). Anti-Proliferative effects of tested herbs seem to be cell type-specific, as extracts did not show growth inhibitory effects against normal Vero cell lines at tested doses. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for in vitro anti-proliferative activity, and n = 7 for in vivo testing). For in vitro activity Asterisks ** and *** represent significance difference from MO group at p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001, ++ and +++ represent significance difference from TO group at p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001 respectively. For in vivo experiment asterisks ***, **, * represents significance at p < 0.0001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.05 vs. control group. +++ Represents significance at p < 0.0001 vs. APAP group. # represents significance at p < 0.05 vs. APAP + MO group. / Represents significance at p < 0.05 vs. APAP + TO group. Non-significant difference (p > 0.05) was recorded between control and extract alone (MO, TO and UD) treated group in all parameters (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests). MO: Melissa officinalis, TO: Taraxacum officinale and UD: Urtica dioica.

In vitro anti-proliferative activity

In vivo antioxidant and oxidative stress biomarkers

Groups

HT 29 IC50 (µg/ml)

HCT 116 IC50 (µg/ml)

Protein (µg/mg Tissue)

MDA (nM/min/mg protein)

GSH (µM/gtissue)

SOD (U/mg protein)

POD (U/min)

Saline

N/A

N/A

4.66 ± 0.05

3.5 ± 0.156

19.98 ± 0.28

1.55 ± 0.06

13.40 ± 0.23b

MO

84.50 ± 2.43

88.40 ± 2.54

4.68 ± 0.04+++

3.47 ± 0.112+++

20.08 ± 0.28+++

1.56 ± 0.07+++

13.41 ± 0.23+++

TO

53.25 ± 2.11***

73.90 ± 2.36**

4.71 ± 0.15+++

3.45 ± 0.087+++

20.11 ± 0.16+++

1.54 ± 0.08+++

13.44 ± 0.27+++

UD

35.30 ± 1.86***,++

49.80 ± 1.85***,+++

4.67 ± 0.13+++

3.51 ± 0.504+++

18.38 ± 0.29+++

1.53 ± 0.05+++

13.42 ± 0.25+++

APAP

N/A

N/A

1.19 ± 0.05***

9.97 ± 0.337***

10.08 ± 0.28***

0.39 ± 0.03***

7.23 ± 0.39***

APAP + MO

N/A

N/A

4.53 ± 0.11+++

4.75 ± 0.107*,+++

17.34 ± 0.11+++

1.31 ± 0.04*,+++

12.57 ± 0.44

APAP + TO

N/A

N/A

4.61 ± 0.16+++

4.14 ± 0.06+++

18.32 ± 0.19+++

1.35 ± 0.03*,+++

12.50 ± 0.66

APAP + UD

N/A

N/A

4.52 ± 0.13+++

4.95 ± 0.09**,+++,/

15.83 ± 0.21*,+++

1.29 ± 0.05*,+++

9.21 ± 0.29**,+++,#,/

3.5 In vivo anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effect

Acetaminophen or paracetamol (APAP) is a frequently used antipyretic and analgesic drug. The APAP-induced toxicity model is generally used to investigate the prospective hepatoprotective action of plant extracts/compounds.

3.5.1 Acute toxicity evaluation

MO, TO and UD were found to be safe at all tested doses (up to 3000 mg/kg b.w) and did not induce any detrimental indications in rats like sedation, convulsions, diarrhea, and irritation. During the 72 h of assessment, no mortality was observed. Therefore, one-tenth of the maximum dose, 300 mg/kg b.w. was used for in vivo evaluations.

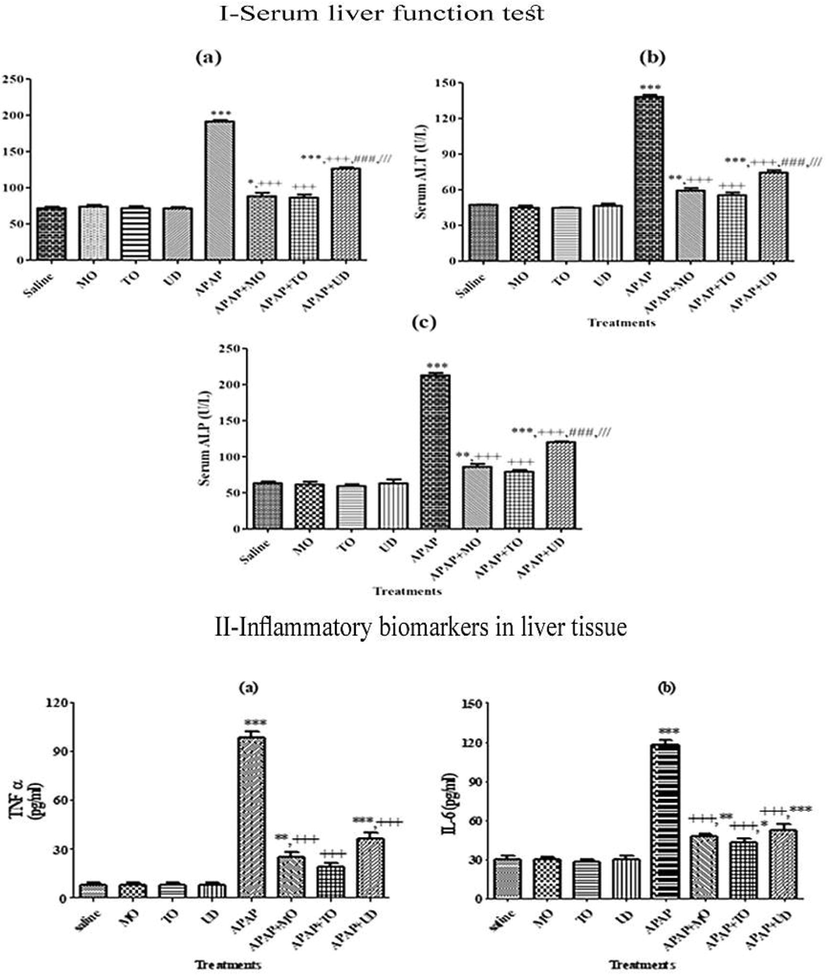

3.5.2 Effect of herbal extracts on hepatic markers in serum

Administration of APAP in rats by oral route caused liver damage as indicated by a significant increase in serum enzymes ALP, AST, and ALT activity as compared with the control group (Fig. 4 I; a, b, and c). The increase in AST and ALT levels may be due to increased LPO. Co-administration of rats with MO, TO and UD extracts with APAP significantly restored the hepatic marker levels in serum towards normal values. A significant increase in serum activities of AST and ALT considered as marker enzymes of hepatocyte cytolysis. Our results are in line with previous findings that demonstrated the ameliorating potential of MO against Malathione induce alterations in hepatic function markers (Sief et al., 2015).

I Effect of MO, TO and UD on serum liver function tests (LFTs). II: Effect on inflammatory biomarkers in Liver tissues of various treatment groups. Values are shown as Mean ± SEM (n = 7). *, **, *** indicate significance vs. saline group at p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001 probability level, +, ++, +++ indicate significance from the APAP group at p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, ### represents significance at p < 0.0001 vs. APAP + MO group. /// Represents significance at p < 0.0001 vs. APAP + TO group. Non-significant difference (p > 0.05) was recorded between control and extract alone (MO, TO and UD) treated group in all parameters (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests). APAP: Acetaminophen/paracetamol, MO: Melissa officinalis, TO: Taraxacum officinale and UD: Urtica dioica.

3.5.3 Effect of herbal extracts on pro-inflammatory biomarkers in hepatic tissue

A more evident approach to assess inflammation is to measure the extent of circulating cytokines. Therefore, the extract/compound exerting an anti-inflammatory activity might also demonstrate hepatoprotective activity. Induction of hepatotoxicity by APAP significantly (p < 0.0001) increased serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6 compared to control and extract alone treated groups (Fig. 4II; a, and b). Our results are similar to reports of James and coworkers suggested that TNF-α and interleukins are released in response to APAP intoxication and are responsible for certain pathological manifestations of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity (James et al., 2005). Among the tested herbs, TO showed a more significant reduction in TNF-α and IL6 levels compared to MO (p < 0.05) and UD (p < 0.001) respectively. The ability of tested herbs specifically TO to inhibit inflammatory cytokine production might be associated with its benefits in the treatment of various inflammatory conditions.

3.5.4 Measurement of oxidative stress markers and antioxidants in the liver

The combination of hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity synergistically prevents the initiation and progression of hepatocellular injury. We observed that APAP treatment resulted in substantial (p < 0.0001) lessening in liver tissue soluble protein as compared to control and MO, TO and UD alone treated groups (Table 5). Co-treatment with MO, TO and UD significantly (p < 0.0001) restored tissue protein content in comparison to APAP alone treated group. Oxidative stress has been reflected as one of the underlying mechanisms of APAP-persuaded acute organ injury. APAP-induced significant (p < 0.0001) intensification in MDA levels as compared to control and extracts alone treated groups. Co-treatment with MO, TO and UD resulted in a diminution in the MDA levels. MO and TO administration seems to be more effective in reducing the APAP-induced oxidative trauma compared to UD. Besides that, previous findings endorsed MO, TO and UD antioxidant activity (Koksal et al., 2011; Colle et al., 2012). The ability of MO and TO exert hepatoprotective activity possibly via its antioxidant action.

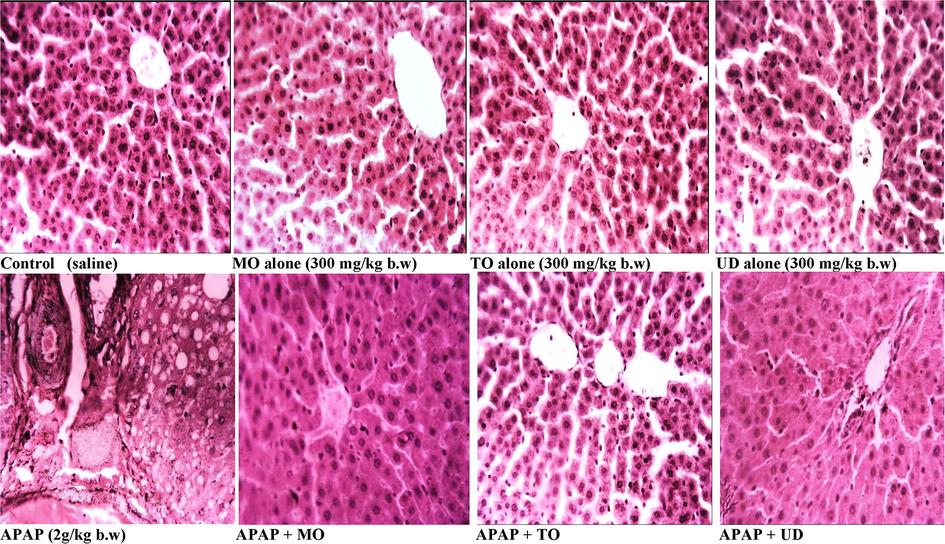

3.6 Histopathological examination

Histopathological observations demonstrated that the control group showed normal lobular architecture and hepatic cells with intact cytoplasm and well-defined sinusoids (Fig. 5) The section of APAP intoxicated liver, exhibited massive necrosis, presence of hemorrhage, and inflammation with infiltration of lymphocytes. Interestingly, these pathological changes were found to be reduced with treatment with MO, TO and UD indicating the extract’s ability to reverse the APAP-induced hepatic injury. The presence of marked necrosis, hemorrhage, and inflammation following treatment with APAP was shown in other studies as well (Mahmood et al., 2014). TO seems to be more protective in preventing liver damage. Histological study apprehends our biochemical findings. MO, TO and UD persuaded hepatoprotective action is proposed to conceivably implicate the synergistic actions of flavonoids, saponins, terpenoids, and tannins (Le Tran et al., 2002; Pan and Lai, 2010).

Histopathology sections from various treatment groups (H&E staining, magnification 40X). Representative section of liver from the control and extracts alone (300 mg/kg b.w oral dose) treated groups showed the normal morphology of tissue. APAP (2 g/kg b.w oral dose) treated rat liver exhibiting greater cellular injuries, loss of hepatic tissue structure organization and assortment of inflammatory cells. Treatment of rats with MO, TO and UD protect liver from APAP induced hepatic injury:Acetaminophen/paracetamol, MO: Melissa officinalis, TO: Taraxacum officinale and UD: Urtica dioica.

4 Conclusion

Present study provided scientific proof for the antioxidant, anticancer, and hepatoprotective activities of MO, TO and UD. The occurrence of several bioactive compounds validates their use for the cure of various ailments by traditional practitioners and conveys supportive data for future studies that will lead to their consumption in cancer, oxidative stress, and anti-inflammatory remedies. In-depth examinations are in progress to conclude the possible hepatoprotective mechanism (s) involved and to isolate and identify the responsible bioactive compounds from the tested herbal extracts. However, anticancer potential of MO, TO, and UD warrants further examinations as a potential nutraceutical or functional food for cancer prevention.

5 Limitations of the study

Future studies are needed to confirm the findings obtained in our study using molecular tools and immune-histochemical techniques. Additionally, due to lack of funding presently we were unable to analyze the details of the signaling mechanism involved in the anti-inflammatory and anticancer potential of selected herbs. Therefore, investigating the detailed mechanism of protection and how these edible herbs induce various pharmacological activities with special focus on the anticancer potential in tumor models should be the focus of further investigations.

6 Declarations

6.1 Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval (# 0236) was taken from the Experimental Animal Care Committee, Department of Animal Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Not applicate

6.2 Consent for publication

Not applicable

6.3 Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

6.4 Authors’ contributions

SR and TA made significant contributions to conception, design, experimentation, acquisition, and interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. DA, AA, MA, AAA, and RAC made a substantial contribution to experimentation and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through research group no. RGP-193.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their heartfelt thankfulness to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University, KSA for its support through the research group no. (RGP-193).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Comparison of nutritional properties of Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) flour with wheat and barley flours. Food Sci. Nutrit.. 2016;4(1):119-124.

- [Google Scholar]

- Afsar, T., S. Razak, A. J. L. I. h. Almajwal and disease (2019). “Effect of Acacia hydaspica R. Parker extract on lipid peroxidation, antioxidant status, liver function test and histopathology in doxorubicin treated rats.” 18(1): 126.

- Evaluation of antioxidant, anti-hemolytic and anticancer activity of various solvent extracts of Acacia Hydaspica R. Parker aerial parts. BMC Complem. Altern. Med.. 2016;16(1):258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer activity, antioxidant activity, and phenolic and flavonoids content of wild Tragopogon porrifolius plant extracts. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med.. 2016;2016(1):7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Free radical scavenging and COX-2 inhibition by simple colon metabolites of polyphenols: a theoretical approach. Comput. Biol. Chem.. 2016;65:45-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Casuga, F. P., A. L. Castillo and M. J.-A. T. J. A. P. J. o. T. B. Corpuz (2016). “GC–MS analysis of bioactive compounds present in different extracts of an endemic plant Broussonetia luzonica (Blanco)(Moraceae) leaves.” 6(11): 957-961.

- On the role of 2, 3-dihydro-3, 5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-(4H)-pyran-4-one in antioxidant capacity of prunes. Eur. Food Res. Technol.. 2011;233(3):367-376.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antityrosinase and antimicrobial activities of furfuryl alcohol, furfural and furoic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2013;57:151-155.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of dandelion (taraxacum officinale) root and leaf on cholesterol-fed rabbits. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2010;11(1):67-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Colle, D., L. P. Arantes, R. Rauber, S. E. C. de Mattos, J. B. T. d. Rocha, C. W. Nogueira and F. A. A. Soares (2012). “Antioxidant properties of Taraxacum officinale fruit extract are involved in the protective effect against cellular death induced by sodium nitroprusside in brain of rats.” Pharmaceutical biology 50(7): 883-891.

- Cooper, K. M., Caddell, A., Elliott, C. T., & Kennedy, D. G. (2004). Production and characterisation of polyclonal antibodies to a derivative of 3-amino-2-oxazolidinone, a metabolite of the nitrofuran furazolidone. Analytica Chimica Acta, 520(1-2), 79-86.

- Antimutagenic and antioxidant activity of a protein fraction from aerial parts of Urtica dioica. Pharm. Biol.. 2015;53(6):935-938.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-proliferative effect of Melissa officinalis on human colon cancer cell line. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr.. 2011;66(4):328-334.

- [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS analysis of bioactive compounds in the methanol extract of Clerodendrum viscosum leaves. Pharmacognosy Res.. 2015;7(1):110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antitumor activity of palmitic acid found as a selective cytotoxic substance in a marine red alga. Anticancer Res.. 2002;22(5):2587-2590.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytokines and toxicity in acetaminophen overdose. J. Clin. Pharmacol.. 2005;45(10):1165-1171.

- [Google Scholar]

- Khajuria, V., Gupta, S., Sharma, N., Kumar, A., Lone, N. A., Khullar, M., ... & Ahmed, Z. (2017). Anti-inflammatory potential of hentriacontane in LPS stimulated RAW 264.7 cells and mice model. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 92, 175-186.

- Antioxidant activity of melissa officinalis leaves. J. Med. Plants Res.. 2011;5(2):217-222.

- [Google Scholar]

- Le Tran, Q., I. K. Adnyana, Y. Tezuka, Y. Harimaya, I. Saiki, Y. Kurashige, Q. K. Tran and S. J. P. m. Kadota (2002). “Hepatoprotective effect of majonoside R2, the major saponin from Vietnamese ginseng (Panax vietnamensis).” 68(05): 402-406.

- Mahmood, N., S. Mamat, F. Kamisan, F. Yahya, M. Kamarolzaman, N. Nasir, N. Mohtarrudin, S. Tohid and Z. Zakaria (2014). “Amelioration of paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rat by the administration of methanol extract of Muntingia calabura L. leaves.” BioMed research international 2014.

- Ethnomedicinal practices and conservation status of medicinal plants of North Kashmir Himalayas. Res. J. Med. Plant. 2011;5(5):515-530.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A. H., A. A. Khuroo, G. Dar and Z. Khan (2011). “Ethnomedicinal uses of some plants in the Kashmir Himalaya.”

- Hepatoprotective potential of ethanolic extract of Pandanus odoratissimus root against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci.. 2015;7(1):45.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of melissa officinalis leaves and stems ethanolic extracts in terms of antioxidant, cytotoxic, and antiproliferative potential. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med.. 2018;2018:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective role of dandelion against acute liver damage induced in albino rats. J. Nat. Prod.. 2008;4(2)

- [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, A., Baskaran, S. A., Amalaradjou, M. A. R., & Venkitanarayanan, K. (2015). Anticarcinogenic properties of medium chain fatty acids on human colorectal, skin and breast cancer cells in vitro. International journal of molecular sciences, 16(3), 5014-5027.

- Pan, M.-H., C.-S. Lai, C.-T. J. F. Ho and function (2010). “Anti-inflammatory activity of natural dietary flavonoids.” 1(1): 15-31.

- Antifungal and antioxidant activity of fatty acid methyl esters from vegetable oils. Anais Acad. Brasil. Ciências. 2017;89(3):1671-1681.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pirbalouti, A. G., M. Nekoei, M. Rahimmalek, F. J. B. Malekpoor and A. Biotechnology (2019). “Chemical composition and yield of essential oil from lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) under foliar applications of jasmonic and salicylic acids.” 19: 101144.

- Prawal Verma, Anand Singh, Laiq-ur-Rahaman and J. R. Bahl (2015). “Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) an herbal medicinal plant with broad therapeutic uses and cultivation practices: A review.” International Journal of Recent Advances in Multidisciplinary Research Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2(11): 5.

- Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect of conjugated linolenic acid isomers against streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Br. J. Nutr.. 2012;108(6):974-983.

- [Google Scholar]

- Salyer, J. T. (2011). “Effect of Soyasaponin Fractions on Human Colon Cancer Cells.”

- Ameliorative role of melissa officinalis against hepatorenal toxicities of organophosphorus malathion in male rats. MOJ Toxicol. 2015;1(3):00013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sivasubramanian, R., & Brindha, P. (2013). In-vitro cytotoxic, antioxidant and GC-MS studies on Centratherum punctatum Cass. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci, 5(3), 364-367.

- Sova, M. (2012). Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of cinnamic acid derivatives. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry, 12(8), 749-767.

- Rani, P., Pal, D., Hegde, R. R., & Hashim, S. R. (2016). Acetamides: chemotherapeutic agents for inflammation-associated cancers. Journal of Chemotherapy, 28(4), 255-265.

- Wang, H., Jenner, A.M., Lee, C.Y.J., Shui, G., Tang, S.Y., Whiteman, M. ... & Halliwell, B., 2007. The identification of antioxidants in dark soy sauce. Free Radical Research 41.

- Alpha-ketoglutarate: physiological functions and applications. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul). 2016;24(1):1-8.

- [Google Scholar]