Translate this page into:

Fluorescent pseudomonads (FPs) as a potential biocontrol and plant growth promoting agent associated with tomato rhizosphere

⁎Corresponding author. shanmugaiahv@gmail.com (Shanmugaiah Vellasamy)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A total of 87 FPs have been isolated from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) rhizosphere and evaluated by dual plate assay method for the antimicrobial activity of Ralstonia solanacearum. Of which, 30 FPs showed antagonistic activity against R. solanacearum with the zone of inhibitions (ZOI) ranging from 19 mm to 28 mm. Similarly, antagonistic FPs significantly controlled various fungal phytopathogens such as Rhizoctonia solani (6.3 mm−20 mm), Macrophomina phaseolina (8.7 mm−19.3 mm), Fusarium oxysporum (7.3 mm−30.7 mm), and Sclerotium rolfsii (5.3 mm−21 mm). The cell-free culture filtrate of Pseudomonas sp VSMKU3054 significantly suppressed the fungal pathogens and increased the root and shoot length of the tomato seedlings compared to the control. Furthermore, the antagonistic FPs effectively produced lytic enzymes and antimicrobial traits such as amylase (6), protease (30), cellulase (28), pectinase (12), chitinase (22), gelatinase (27), siderophore (28), hydrogen cyanide (25), phosphate solubilization (30), and Indole acetic acid (IAA) (23). Genetic diversity of FPs was assessed by BOX-PCR with specific primers revealed that two distinct clusters were observed, whereas, RFLP analyses were showed that 5 to 16 bands ranged from 75 bp to 1.2 bp with two major clusters using restriction enzyme HaeIII. The antibiotic encoding genes were detected from FPs, of which 10 FPs were positive for 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG), 9 FPs were positive for pyoleuterin (PLT), 10 FPs were positive for hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and none of them obtained pyrrolnitrin (PRN) with respective primers. Based on the superior antagonistic isolates against R. solanacearum and phytofungal pathogens and other antimicrobial traits, the isolate VSMKU3054 was selected for further studies. Based on the morphological, physiological and 98% of 16 s rDNA sequence similarity, the selected isolate VSMKU3054 was identified as Pseudomonas fluorescens. Further, the potential isolate P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 and cell free culture filtrate remarkably enhance tomato seedling growth such as root and shoot length, fresh and dry weight and vigor index compared to control. This study indicated that rhizospheric isolates of FPs have more potential for plant growth promotion and plant protection from plant pathogenic microbes.

Keywords

Fluorescent pseudomonads

Ralstonia solanacearum

Fungal pathogens

Antibiotic encoding genes

Antimicrobial traits and plant growth promotion

1 Introduction

Beneficial microbes like Pseudomonas spp are colonizing plant roots and protect the plants from plant pathogens by the secretion of plant growth promoting substance, antimicrobial compounds and pathogenic related proteins (Ashajyothi et al., 2020; Agaras et al., 2020). Plant growth prompting rhizobacteria (PGPR) were includes Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Pseudomonads, Bacillus, Streptomyces, Enterobacter, Clostridium, Burkholderia, and Stenotrophomonas (Sheoran et al., 2015). FPs act as PGPR and produce a multiple level of plant growth-promoting substances like indole −3- acetic acid (IAA) (Ricci et al., 2019), aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase (Win et al., 2018) and insoluble phosphates are solubilized by phosphate solubilizing bacteria like FPs (Naik et al., 2008). Root associated FPs are controlled various phytopathogens with different mechanisms such as volatile substances, antibiosis and hydrolytic enzymes such as chitinase and protease production (Shanmugaiah et al., 2008; Köhl et al., 2019).

Antagonistic microorganisms are mostly isolated from rhizosphere, among them Pseudomonas spp is a promising biocontrol agent without extensive studies (Xue et al., 2013). FPs naturally occurs in rhizosphere; they are non-pathogenic and produce secondary metabolites to control the soil-borne plant pathogens (Raaijmakers et al., 2002). Pseudomonas spp are plant growth prompting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and potential biocontrol agent to suppress various plant pathogenic bacteria like R. solanacearum (Lemessa and Zeller, 2007). Furthermore, FPs is a prominent group of rhizospheric microorganisms that are ecologically very important microorganism for plant growth promotion and biocontrol properties (Salman, 2010).

In recent days, due to high demand of tomato production based on its high potential both food and agriculture sector, tomato production has been increased. About 15 to 55% tomato crop loss has been reported by bacterial wilt vascular pathogen R. solanacearum. Whereas in India, on average up to 10 to 20% were seen in some cases 90% (Rai et al., 2017). Chemically synthesis antibiotics, fungicides, pesticides, and weedicides have been used for several years for the protection of plant fungi and bacterial pathogens. But many regulations on the use of chemicals have been enforced in recent days. Because, they are creating major environmental and public risks and health hazards. Significant problems have been caused by chemical-based treatments, such as decreased productivity, fruit taste and yield loss, because of chemical fungicide persistent in to soil and environment. Moreover, the chemical fungicide could not be degradable from the environment. Hence it will create more environment problems and health hazards (Pertot et al., 2008). In addition, chemical treatments for plant diseases are costly and harm to the environment and public health (Shanmugaiah et al., 2010, 2015).

In this contest alternative strategies were developed for the management of plant diseases and encourage plant growth instead of using chemical fertilizers, fungicides and pesticides for the development of environment friendly and sustainable ecosystem. Hence, the use of antagonistic microorganism for plant growth-promotions are wise choice with a broad spectral and widespread alternative approach to control plant pathogens (Shanmugaiah et al., 2006; Harikrishnan et al., 2014). Studies were shown that the management of bacterial wilt disease and other phytopathogens could be successfully controlled by the application of biocontrol agents like Pseudomonas sp. (Shanmugaiah et al., 2010; Nithya et al., 2020; Elsayed et al., 2020), Bacillus (Shanmugaiah et al., 2008; Rais et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019), Streptomyces (Harikrishnan et al., 2016; Kaur et al., 2019) and Trichoderma (Shanmugaiah et al., 2009; Mazrou et al., 2020) to control various plant pathogenic bacterial and fungal organism (Vanitha and Umesha, 2011).

In addition, to understand molecular plant microbe interaction and ecological function in the rhizosphere and other various molecular and biotechnological applications for the rhizosphere and root residing bacteria and their biocontrol potential are most essential. Rice, banana, sugarcane, and tomato are most important food crops in the world and they are widely grown in developing countries. But, the bacterial and fungal pathogens are constrains and most important for the production of rice, banana, sugarcane, tomato, and other crops (Naik et al., 2008). Indiscriminate use of chemical fungicides and chemically synthesized antibiotics in agriculture is detrimental to the environment and lethal to other beneficial micro-organisms for the control of phytopathogens. (Giorgio et al., 2016). Hence, in this juncture need to develop antagonistic microbes are resistant towards pathogenic microbes. Further, the multiple applications of antibiotics and plant growth-promoting molecules and other substance produced by Pseudomonas spp are most important to study their diversity, through which to find out novel indigenous bio inoculants for sustainable and bioorganic fertilizer without causing any environmental pollution and harmful effect to farmers.

The indigenous antagonistic rhizobacteria are potentially enhanced the control of soil-borne plant pathogens because native isolates are more effective than exotic isolates (Cabanas et al., 2018; Chenniappan et al., 2019). Pseudomonas spp are well known producer of antimicrobial metabolites like DAPG, but as per our literature survey FPs from tomato rhizosphere and it also modify stress hormones and antioxidant expression in abiotically stressed plants that would be useful for initiation of plant defense mechanisms (Duke et al., 2017). Hence, the present study was carried out with the following objectives i) isolation and characterization of FPs for the effective control of phytopathogens ii) Detection of antibiotic encoding gens from FPs isolated from tomato rhizosphere iii) Functional characterization and plant growth promoting traits of FPs iv) To study, the genetic diversity of FPs by RFLP and BOX-PCR.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Isolation of fluorescent pseudomonads

Samples of the tomato rhizosphere were collected from various locations in the Madurai district, Tamil Nadu, India. 10 g of tomato rhizosphere samples were shaken in 90 ml of sterilized water at 120 rpm for 30 min (Shanmugaiah et al., 2006). The soil suspension was diluted serially and spread on King's B agar (King et al., 1954). The plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C and viewed at 365 nm under a UV illuminator. The purified single colonies were preserved in 30% glycerol at −80 °C.

2.2 Screening of FPs against phytopathogens

The antagonistic behaviors of all FP isolates were screened towards bacterial tomato wilt pathogen R. solanacearum on Nutrient Agar (NA) by dual plate assay method (Zhou et al., 2012). The R. solanacearum (107 CFU/ml), similarly all FPs isolates (107 CFU/ml) inoculated on Nutrient Agar with three replicates on the periphery of Petri plate. After 2 days of incubation at 28 °C, the inhibition zone was measured.

Similarly, FPs isolated from tomato rhizosphere were assayed against phyto fungal pathogens such as R. solani, S. rolfsii, M. pheaseolina, and F. oxysporum on PDA medium in triplicate by dual plate assay method as per Shanmugaiah et al. (2010). Nine millimeters of mycelial discs were cut from the young growing edge of the fungus with a sterilized cork borer and placed in the centre of the Petri dish. The 24 bacterial isolates were punctiform inoculation aseptically at the periphery of the PDA plate and incubated for 5 days at 28 ± 2 °C. For every isolate, there were three duplications kept. The inhibition zone was measured in the nearest millimeter between the two cultures.

2.3 Biochemical tests of FPs

All FPs were chosen for further characterization by standard biochemical tests based on the promising antagonistic behavior compared to the control (Nithya et al., 2019). The following tests were conducted for Gram’s reaction, catalase and oxidase activity, Indole, VP, MR, citrate utilization and shape of the isolates. Outcomes of these assessments were recorded as either positive or negative.

2.4 Production of lytic enzyme and antimicrobial traits

All antagonistic isolates of FPs were tested for hydrolytic enzyme production by the qualitative assay method (Shanmugaiah et al., 2008). The hydrolytic enzyme production assay was performed to determine the production of protease, gelatinase, amylase, cellulase, chitinase, and pectinase for all isolates of FPs on nutrient agar supplemented with 1% of the respective substrates (Ayyadurai et al., 2006). A clear zone around the colonies of FPs was showed hydrolytic enzyme activity after 48 h of incubation.

2.5 Antimicrobial metabolites characterization

2.5.1 Hydrogen cyanide (HCN)

HCN development was accomplished as stated by Lorck (1948). Briefly, fresh isolates of FPs were grown in nutrient sucrose medium (NSM) supplement with 4.4% of glycine. Sterilized Whatman No1 filter paper soaked with a solution containing 1% picric acid and 2% sodium carbonate and placed on the lid of the petri dish. To prevent gas exchange from the inside of the Petri dish, the plates were tightly sealed with parafilm and incubated for 48 h. A change in the color of the filter paper from yellow to orange, indicating the production of HCN.

2.5.2 Siderophore

Siderophore creation by FPs was determined by Chrome Azurole S (CAS) assay by the method of Alexander and Zuberer (1991). The FPs was inoculated in cetrimide agar and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, 0.7% of CAS agar was superimposed on cetrimide agar and the plates were incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. The production of siderophore was indicates the change of color from blue to brownish orange.

2.5.3 Indole acetic acid (IAA)

The development of indole acetic acid by the FPs isolates was evaluated using the method of Bric et al. (1991). In King's B broth, the FPs were inoculated with 0.4 percent

L-tryptophan supplementation and incubated for 24 h. After 10,000 rpm centrifugation for 15 min, the 2 ml of cell-free culture filtrate was combined with 4 ml of reagent from Salkowski (1 ml of 0.5 M FeCl3 in 50 ml of 35% HClO4). The mix was incubated for 20 min at room temperature.

2.5.4 Phosphate solubilization

Each isolates of FPs were punctiform inoculation on Pikovskaya’s agar (Pikovskaya, 1948). At 28 ± 2 °C for 48 h, the plates were incubated. The creation of a clear zone around the colony was considered as positive for solubilization of insoluble phosphate compared to control.

2.6 DNA extraction

By the heat lysis method, genomic DNA was extracted from FPs (Keel et al., 1996). Briefly, a loopful of fresh colonies of FPs were suspended in 100 µl of lysis solution (50 mM KCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 10 mM Tris HCl, pH-8.3) and incubated at 99 °C for 10 min. After that bacterial cell suspension was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 1 min. For 30 min, the heat-lysed bacterial suspension was frozen at −20 °C.

2.7 BOX – PCR and RFLP analysis for genomic fingerprinting

All the antagonistic isolates of FPs were subjected to BOX-PCR and RFLP analysis was performed with the procedure followed from previous studies (Nithya et al., 2020; Rana et al., 2014; Saikia et al., 2011) BOX-PCR are carried out with BOX-A1R primer (5′-CTACGGCAAGG CGACGCTGACG-3′). To perform RFLP analysis, amplified 16S rDNA product are digest with Hae III restriction enzyme. BOX PCR and RFLP genomic fingerprinting computer assisted analysis were performed by GelClust software to construct phylogenetic tree, for which neighbor-joining method and unweighted pair group with mathematical average (UPGMA) algorithms were used (Moin et al., 2020).

2.8 Detection of antimicrobial encoding genes by PCR

Antibiotic encoding genes such as 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol (phlD), pyoluteorin (pltB), pyrrolnitrin (prnA), and hydrogen cyanide (hcnBC) were detected from 30 FPs and amplified by PCR (Smart PCR, Cyber Lab, USA) using previously reported gene-specific respective primers (Table 1). As reference strains, positive controls were used, P. fluorescens CHAO, and P. fluorescens Pf5. 25 µl of PCR reaction was carried out included 25 ng of template DNA, 1x thermo-DNA buffer, 1.5 mmol−1 MgCl2, 0.2 mmol−1 of each dNTP, 20 pmol of each primer, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (GeNet Bio, India). A 5 µl of aliquot of each amplification product was electrophoresed on a 1 percent agarose gel in 1x Tris-acetate- EDTA (TAE) buffer at 50v for 45 min, stained with ethidium bromide, and PCR products were visualized with Gel documentation. phlD: 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol; pltB: pyoluteorin; prnA: pyrrolnitrin and hcnBC: hydrogen cyanide.

Primers

Encoding gene

Sequence (5′ → 3′)

PCR Conditions

Product size (bp)

References

B2BF

phlD

ACCCACCGCAGCATCGTTTATGAGC

95 ˚C for 3 min, 30 cycles at 94˚C for 60 sec, 57.5 ˚C for 60 sec, 72˚C for 60 sec, 72 ˚C for 5 min, 4 °C-α.

629

Immanuel et al., 2012

BPR4

CCGGTATGGAAGATGAAAAAGTC

PltB -F

pltB

CGGAGCATGGACCCCCAG

95 ˚C for 2 min, 30 cycles at 94 ˚C for 60 sec, 67 ˚C for 45 sec, 72 ˚C for 60 sec, 72 ˚C for 10 min, 4 °C-α.

850

Mavrodi et al., 2001

PltB -R

GTGCCCGATATTGGTCTTGACC

PrnA -F

prnA

GTGTTCTTCGACTTCCTCGG

95 ˚C for 3 min, by 30 cycles at 94 ˚C for 30 sec, 63 ˚C for 45 sec, 72 ˚C for 60 sec, 72˚C for 5 min, 4 °C-α.

1050

de Souza and Raaijmakers 2003

PrnA -R

TGCCGGTTCGCGAGCCAGA

Hen -F

hcnBC

ACTGCCAGGGGCGGATGTGC

95 °C- 3 min; 94 °C for 30 s, 63 °C − 45 s; 72 °C for 1 min for 30 cycles and 72 °C for 5 min, 4 °C-α

600

Ramette et al., 2006

Hen –R

ACGATGTGCTCGGCGTAC

2.9 16 s rDNA identification of Pseudomonas sp. VSMKU3054

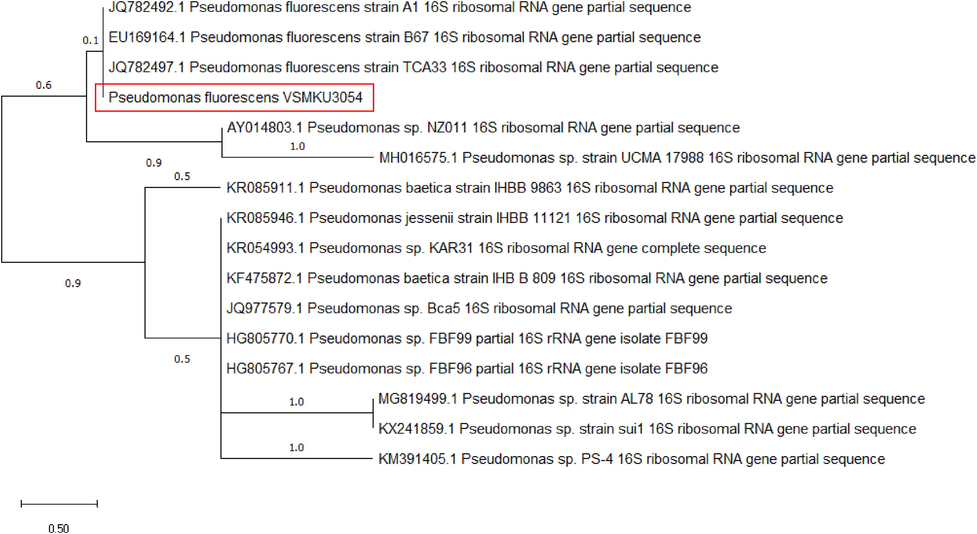

The selected isolates of Pseudomonas sp VSMKU3054 genomic DNA was amplified with 16S rDNA primer 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGTCAGAACGCT-3′) and 1492R (5′- TACGGCTA CCTTGTTACGACTTCACCCC-3′) (Rana et al., 2014). Phylogenetic tree was constructed by unweighted pair group of arithmetic mean analysis method and tree was evaluated by the bootstrap method using the software MEGA 4.

2.10 Influence of P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 on tomato seed germination

Tomato seeds germination was assessed treated with P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 under in vitro conditions. Bacterial wilt susceptible tomato seeds (PKM1) were purchased from Horticultural College & Research Institute, Periyakulam, Theni District, Tamil Nadu, India. The seeds were sterilised with 1 percent sodium hypochlorite for 2 min and washed three times with sterile distilled water, followed by blot drying. P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 and R. solanacearum were grown in the respective medium for 24 h and bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The pellets were resuspended by distilled water and the bacterial cell suspension was adjusted to 0.1O.D. at 600 nm (≈1 X 108 CFU). The seeds were immersed with bacterial cultures for 30 min and seeds were germinated on moist blotter paper placed with 25 Petri dishes. About 25 seeds per plate were placed with the standard procedure as described by the International Seed Testing Association. The plates were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 10 days. The seeds were treated with distilled water was considered as negative control (Vanitha and Umesha, 2011).

2.11 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with statistical tools from SPSS 16.0 (Statistical Software for the Social Sciences). The data in all groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the P-values were < 0.05 the findings were deemed statistically important.

3 Results

3.1 Isolation and antagonistic activity of FPs

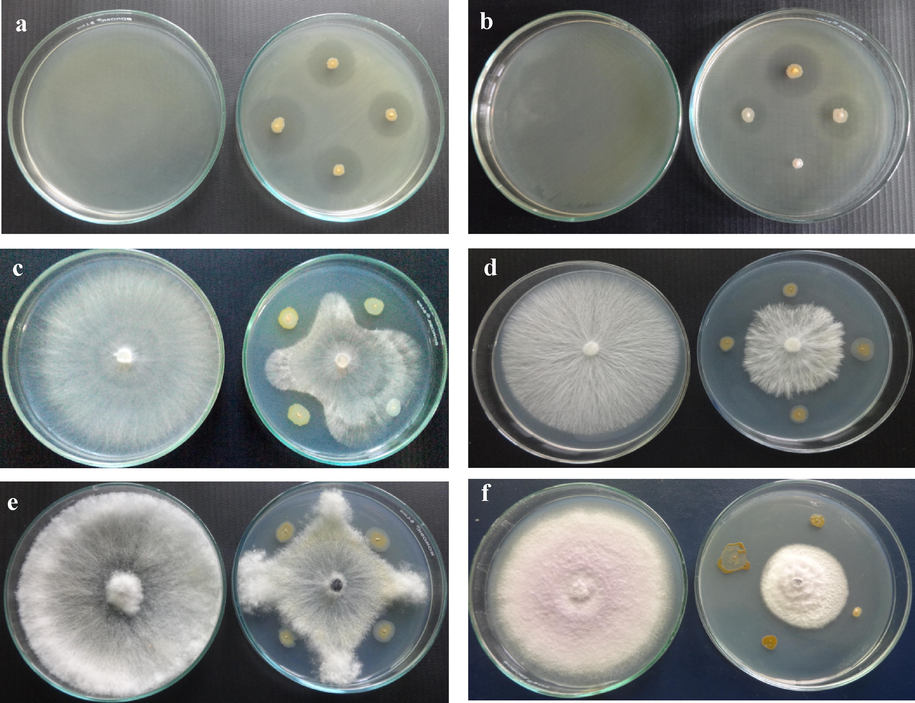

A total of 87 FPs was isolated from tomato rhizosphere. Of which, 30 FPs were exhibited potential antagonistic activity against R. solanacearum. Among them an isolate Pseudomonas sp VSMKU3054 was chosen for additional studies based on the more antibacterial activity against R. solanacearum (28 mm) as compared to control (Table 2 and Fig. 1a & b). All the 30 antagonistic isolates of FPs were exhibited remarkable antifungal activity with various levels of the zone of inhibition (ZOI) against different fungal phytopathogens such as R. solani (20 mm), S. rolfsii (21 mm), M. phaseolina (19.3 mm), and F. oxysporum (30.7 mm) compared to control tested on dual plate. The ZOI ranged from 5 to 31 mm (Table 2 and Fig. 1c–f). Values are triplicates with standard deviation.

Isolates of FPs

R. solanacearum (mm)

R.solani (mm)

S. rolfsii (mm)

M. phaseolina (mm)

F. oxysporum (mm)

VSMKU3001

26.7 ± 1.15

10 ± 1

14.3 ± 1.15

8.7 ± 0.58

8.7 ± 2.08

VSMKU3003

22 ± 0

8 ± 1

11.3 ± 0.58

11 ± 1.15

11 ± 2

VSMKU3004

23.3 ± 0.58

9.3 ± 0.58

9 ± 1

11.7 ± 1.15

8.3 ± 2.08

VSMKU3005

19 ± 1

8 ± 0

7.7 ± 0.58

11 ± 2.65

7.3 ± 0.58

VSMKU3007

22.7 ± 0.58

–

8 ± 0

–

10 ± 1

VSMKU3009

25.7 ± 2.08

7.3 ± 0.58

5.3 ± 0.58

9.7 ± 0.58

8.3 ± 0.58

VSMKU3011

22.7 ± 0.58

8.3 ± 0.58

10.7 ± 0.58

10 ± 1.7

8 ± 1

VSMKU3012

24.3 ± 0.58

12 ± 1

14 ± 0

15.3 ± 2.08

21.7 ± 1.53

VSMKU3021

19.7 ± 0.58

12.7 ± 0.58

13.3 ± 1.15

20 ± 1

25.7 ± 1.53

VSMKU3022

20.3 ± 1.15

12.7 ± 0.58

10.7 ± 0.58

19.3 ± 0.58

26 ± 1

VSMKU3024

20 ± 1

13.3 ± 1.53

14 ± 1

17.7 ± 1.53

27 ± 1

VSMKU3025

19.3 ± 0.58

12.7 ± 1.53

11.7 ± 1.15

18.7 ± 1.53

25 ± 1

VSMKU3029

25 ± 1

12.3 ± 0.58

13.3 ± 0.58

18.7 ± 1.53

25.7 ± 1.15

VSMKU3030

21 ± 1

11 ± 0

14.3 ± 1.15

17.7 ± 1.15

27.7 ± 1.15

VSMKU3032

21 ± 1

10 ± 1

10.7 ± 0.58

16 ± 1

26.3 ± 0.58

VSMKU3034

24.7 ± 1.15

8.7 ± 1.15

10.3 ± 1.53

18 ± 1

26.3 ± 1.15

VSMKU3035

22 ± 1

6.3 ± 1.15

13 ± 0

18.7 ± 0.58

30.7 ± 0.58

VSMKU3036

20.7 ± 0.58

15 ± 1

15.3 ± 0.58

13 ± 1

16.3 ± 2.31

VSMKU3038

21.7 ± 0.58

15.7 ± 1.15

21 ± 1

11 ± 1

16.7 ± 0.58

VSMKU3044

23.4 ± 0.58

14 ± 1

16.6 ± 0.58

14.7 ± 1.53

16 ± 1.73

VSMKU3049

24.3 ± 0.58

16 ± 0

16.7 ± 0.58

14.7 ± 1.53

15 ± 1

VSMKU3054

28 ± 1

16.3 ± 3.21

13.7 ± 1.53

11 ± 1

11.7 ± 0.58

VSMKU3055

22.7 ± 0.58

15.7 ± 0.58

10 ± 0

13.7 ± 0.58

20.3 ± 1.53

VSMKU3062

22.7 ± 2.08

12.7 ± 0.58

13.3 ± 0.58

11.7 ± 0.58

20 ± 1

VSMKU3063

21.7 ± 1.15

12.3 ± 0.58

10 ± 1

13 ± 2.65

20 ± 2.65

VSMKU3065

20.7 ± 2.30

17 ± 1

9.3 ± 1.53

11.7 ± 1.53

14 ± 2.65

VSMKU3066

21 ± 1

15.3 ± 1.53

10.3 ± 1.53

12.3 ± 1.15

15.3 ± 2.08

VSMKU3076

22.7 ± 0.58

18 ± 2

13 ± 0

13.7 ± 1.53

12.7 ± 2.08

VSMKU3078

23.7 ± 0.58

20 ± 0

12.7 ± 0.58

12.3 ± 2.08

13.7 ± 1.53

VSMKU3080

22.3 ± 0.58

18 ± 1

7 ± 1

15.3 ± 1.53

15 ± 1.73

Antagonistic activity of FPs against R. solanacearum and fungal plant pathogens: a & b - R. solanacearum + FPs, c - R. solani + FPs, d - S. rolfsii + FPs, e - M. phaseolina + FPs and f- F. oxysporum + FPs.

3.2 Morphological and physiological characterization

All the antagonistic isolates of FPs were tested for phenotypic characterization by morphological and various biochemical tests. All antagonistic isolates were Gram-negative, rod shape, motile, positive for catalase, oxidase and citrate consumption, whereas negative for IMVIC (Table 3). The productions of hydrolytic enzymes by antagonistic FPs were showed positive with different levels of the zone of clearance such as amylase (6), protease (30), cellulose (28), pectinase (12), gelatinase (27) and, chitinase (22) compared to control (Table 4). + indicates positive reaction; – indicates negative reaction. + indicates positive reaction; – indicates negative reaction.

FP’s

Gram’s Reaction

Shape

Indole

VP

MR

Citrate Utilization

Catalase

oxidase

VSMKU3001

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3003

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3004

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3005

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3007

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3009

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3011

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3012

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3021

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3022

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3024

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3025

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3029

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3030

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3032

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3034

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3035

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3036

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3038

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3044

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3049

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3054

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3055

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3062

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3063

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3065

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3066

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3076

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3078

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3080

–

Rod

–

–

–

+

+

+

FP’s

Amylase

Protease

Cellulase

Pectinase

Chitinase

Gelatinase

Siderophore Production

HCN

IAA

Phosphate Solubilization

VSMKU3001

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

–

+

+

VSMKU3003

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

–

+

+

VSMKU3004

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

–

–

+

VSMKU3005

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

–

–

+

VSMKU3007

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3009

–

+

+

–

–

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3011

–

+

+

–

+

+

–

–

+

+

VSMKU3012

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3021

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3022

–

+

+

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

VSMKU3024

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3025

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3029

–

+

–

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3030

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3032

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3034

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

–

+

VSMKU3035

–

+

+

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3036

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3038

–

+

–

+

–

+

+

+

–

+

VSMKU3044

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

–

VSMKU3049

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3054

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3055

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

–

+

VSMKU3062

–

+

+

+

–

–

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3063

–

+

+

–

–

–

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3065

–

+

+

+

–

+

+

+

–

+

VSMKU3066

+

+

+

+

–

–

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3076

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

VSMKU3078

–

+

+

+

–

+

+

+

–

+

VSMKU3080

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

3.3 Production of antimicrobial and plant growth-promoting traits by FPs

Among 30 FPs, 27 and 25 FPs were showed positive for siderophore and hydrogen cyanide production. All 30 FPs were showed positive for phosphate solubilization. Of the 30 FPs, 23 isolates of FPs were showed positive for the production of Indole acetic acid (IAA) (Table 4).

3.4 Genotypic fingerprinting analysis

3.4.1 Box PCR

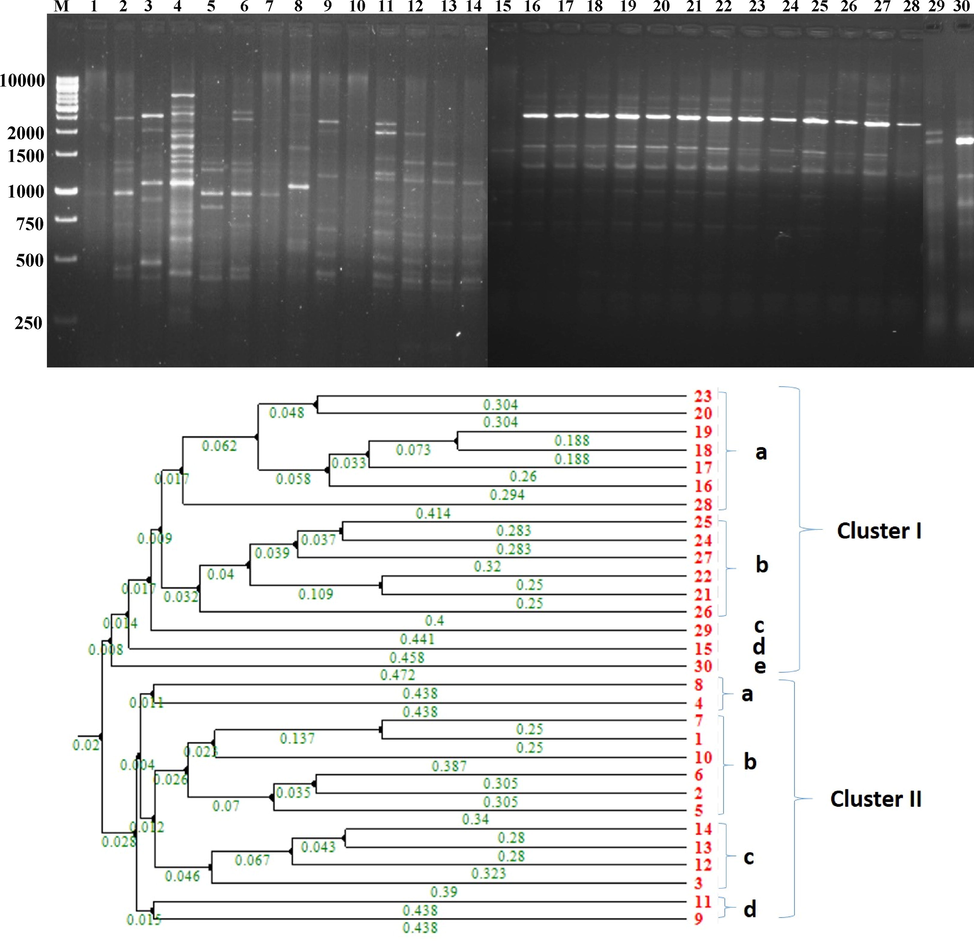

The cluster analysis was performed based on the pair-wise constant similarity with UPGMA of BOX-PCR. A total of two distinct genomic clusters and 85% similarity coefficient generated 16 distinct BOX profiles with 160 bp to 6 kb (Fig. 2a and b). A total of 16 isolates, 60 percent identical to other strains, were grouped into cluster I. Cluster II consisted of 14 isolates which, compared to other strains, were 40% identical. Due to their high degree of genetic heterogeneity, all antagonistic isolates of FPs displayed substantial variations in fingerprinting patterns and distributed into different clusters. The current study showed a high degree of genetic heterogeneity and distribution between different isolates of FPs in different clusters. The present study detected a high degree of genetic variability among different species of FPs based on our findings.

BOX-PCR analysis of FPs. Fig. 2a and b. Dendrogram of BOX-PCR by Neighbor-joining metheod: 1-VSMKU3001, 2-VSMKU3003, 3-VSMKU3004, 4-VSMKU3005, 5-VSMKU3007, 6-VSMKU3009, 7-VSMKU3011, 8-VSMKU3012, 9-VSMKU3055, 10-VSMKU3062, 11- VSMKU3063, 12-VSMKU3065, 13-VSMKU3066, 14-VSMKU3076, 15-VSMKU3078, 16- VSMKU3080, 17-VSMKU3025, 18-VSMKU3029, 19-VSMKU3030, 20-VSMKU3032, 21- VSMKU3034, 22-VSMKU3035, 23-VSMKU3036, 24-VSMKU3038, 25-VSMKU3044, 26- VSMKU3049, 27-VSMKU3054, 28-VSMKU3024, 29-VSMKU3021, 30-VSMKU3022.

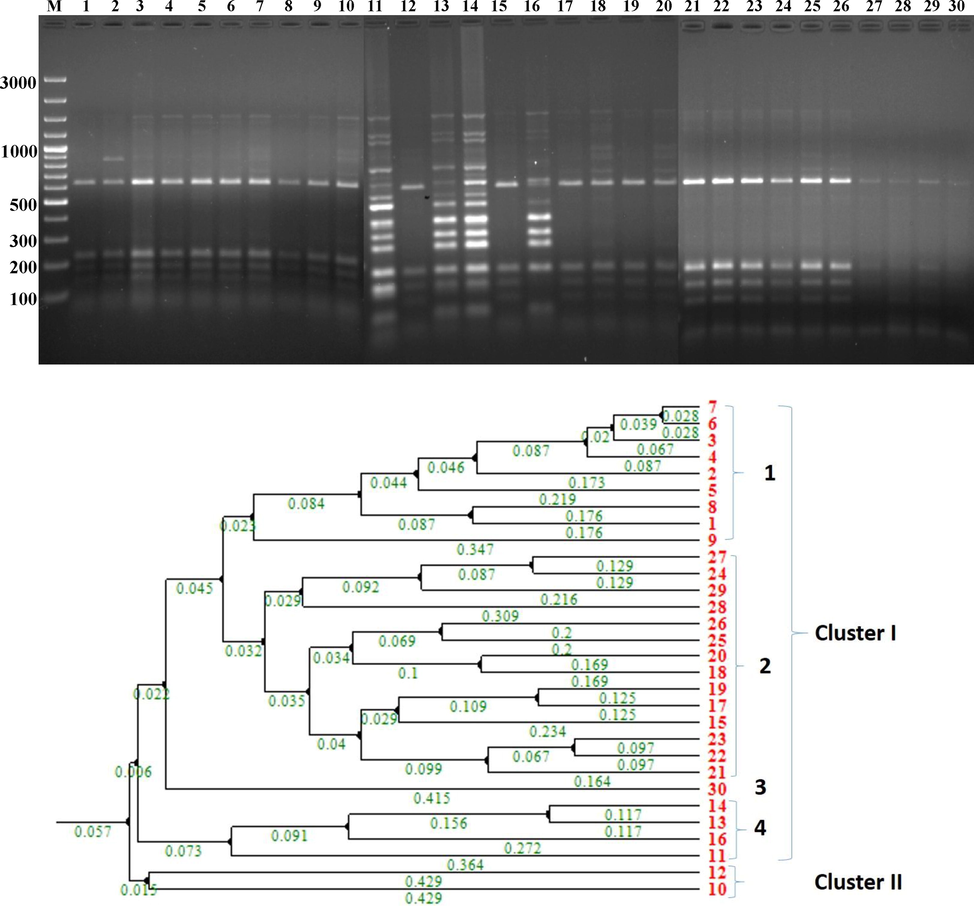

3.4.2 Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)

The PCR product dependent RFLP (16 s rDNA) was performed using a Hae III restriction enzyme with genomic fingerprinting process. A total of 30 FPs and reference strains were amplified with primers 27F and 1492R. Gel electrophoresis of the undigested PCR products were exposed that all the isolates produced a single band, about 1500 bp (Fig. 3a and b). Genetic fingerprinting analysis exhibited massive variation among the isolates of FPs. The fingerprinting pattern after digestion with Hae III exposed 16 different restriction patterns in the range of 75 bp to 1.2kp. A dendrogram was constructed and divided into two major clusters. A total of 28 isolates were grouped in Cluster I and further they were divided into four subs clads. Sub-clads 1 comprises nine isolates, 2 comprising fifteen isolates, 3 comprising one isolate, and 4 comprising four isolates. The cluster II presented only two isolates. The data analysis of RFLP similarities was done using Jaccard’s coefficient.

RFLP analysis of FPs. Fig. 3a and b. Dendrogram of RFLP by UPGMA –Pearson correlation: M−Marker (100 bp), 1-VSMKU3001, 2-VSMKU3003, 3-VSMKU3004, 4-VSMKU3005, 5-VSMKU3007, 6-VSMKU3009, 7-VSMKU3011, 8-VSMKU3012, 9- VSMKU3035, 10- VSMKU3036, 11- VSMKU3021, 12- VSMKU3022, 13- VSMKU3024, 14- VSMKU3025, 15- VSMKU3029, 16- VSMKU3030, 17- VSMKU3032, 18- VSMKU3034, 19- VSMKU3038, 20- VSMKU3044, 21- VSMKU3049, 22– VSMKU3054, 23– VSMKU3055, 24- VSMKU3062, 25- VSMKU3063, 26- VSMKU3065, 27- VSMKU3066, 28- VSMKU3076, 29- VSMKU3078, 30- VSMKU3080.

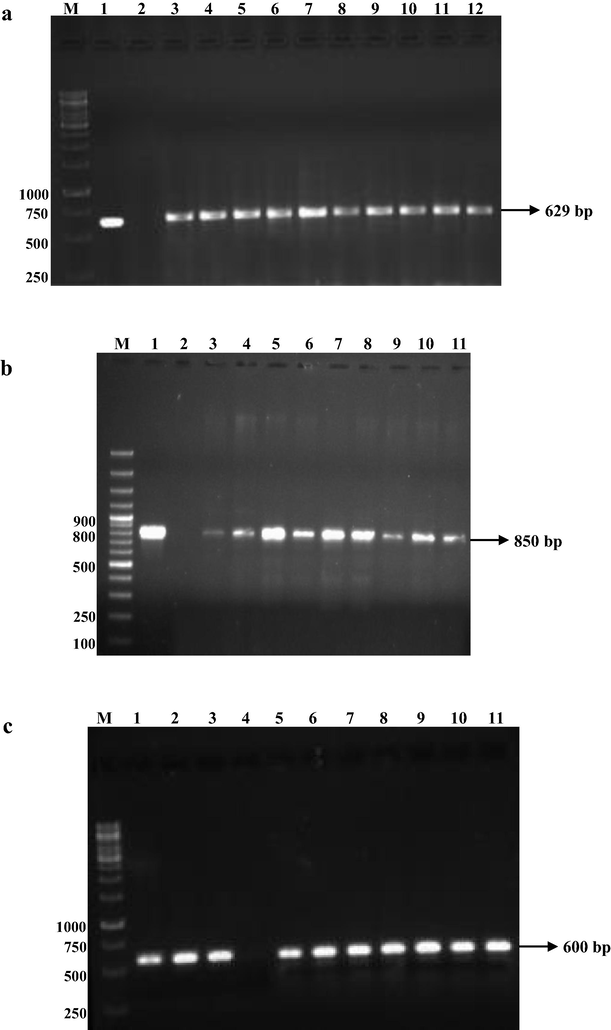

3.5 Detection of antibiotic encoding genes in FPs

The presence of phenolic and polyketide related genes phlD, pltB, prnA, and hcnBC were detected using specific primers. The amplification of DAPG encoding gene with size 629 bp in 10 FPs out of 30 isolates (Fig. 4a), In case of PLT encoding gene, about 12 isolates were identified with an amplicon size of 850 bp out of 30 isolates (Fig. 4b), Similarly, the amplicon size of HCN encoding genes was 600 bp from 26FPs among 30 FPs (Fig. 4c), whereas none of the isolates of FPs did not showed the presence of PRN gene.

Detection of antibiotic encoding genes from antagonistic FPs by PCR. a – DAPG, b. PLT and c. HCN. 4a - M−Marker (1kp), 1-CHAO, 2-Negative control, 3-VSMKU3021, 4-VSMKU3022, 5- VSMKU3024, 6-VSMKU3025, 7-VSMKU3029, 8-VSMKU3030, 9-VSMKU3032, 10- VSMKU3034, 11- VSMKU3049, 12-VSMKU3054. 4b - M−Marker (100 bp), 1-Pf5, 2-Negative Control, 3-VSMKU3065, 4-VSMKU3066, 5-VSMKU3080, 6- VSMKU3036, 7-VSMKU3038, 8-VSMKU3049, 9-VSMKU3054, 10-VSMKU3055, 11-VSMKU3062. 4c - M−Marker (1kp), 1-VSMKU3021, 2-VSMKU3022, 3- VSMKU3024, 4-Negative Control, 5-VSMKU3025, 6- VSMKU3029, 7-VSMKU3030, 8-VSMKU3032, 9- VSMKU3049, 10-VSMKU3054, 11-VSMKU3055.

3.6 16 s rDNA sequence analysis

16 s rDNA gene sequence was carried out subjected to BLAST analysis. The sequence was submitted to NCBI with the GenBank accession no. MH443348. The numerous sequence arrangements was done using CLUSTALW for phylogenetic tree construction, a phylogenetic tree was created using the neighbor-joining method by MEGA4 software. Based on the morphology, physiochemical and 16 s rDNA analysis, the isolate VSMKU3054 was identified as P. fluorescence with 98% similarity comparison with other isolates of Pseudomonas spp nucleotide sequence obtained from NCBI (Fig. 5).

Phylogenetic tree based on 16 s rRNA gene sequence of P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 depicted with other Pseudomonas sp. and GenBank accession no. MH443348.

3.7 Effect of P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 on tomato seed germination

P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 and their cell-free culture filtrate significantly enhanced seed germination of tomato at 108 CFU and 5 ml of cell-free culture filtrate compared to control. Besides, the isolate P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 and their cell-free culture filtrate significantly promoted the length of shoot and root in tomato plants. Fresh and dry weight also increased upon treated with P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 and their cell-free culture filtrate compared to controls (Table 5). Shoot length was remarkably reduced (P < 0.05) in R. solanacearum when compared with control and culture. Similarly, root length and vigor index also strangely decreased in R. solanacearum inoculated tomato seedling compared to control. Date are average of 3 replications; The data in all groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the P-values were < 0.05 the findings were deemed statistically important.

Treatments

Root length (cm)

Shoot Length (cm)

Fresh Weight (g)

Dry Weight (g)

Vigor Index

Control

5.73 ± 0.09

12.9 ± 0.1

0.058 ± 0.0009

0.0025 ± 0.00011

536.23 ± 8.75

Culture

6.5 ± 0.12 acd

13.6 ± 0.1acd

0.063 ± 0.0017

0.0029 ± 0.00015

623.77 ± 23.96 acd

Cell free culture filtrate

5.93 ± 0.12 bd

10.33 ± 0.15 abd

0.056 ± 0.003

0.0021 ± 0.0001

540.5 ± 23.09 bd

R. solanacearum

3.9 ± 0.08 abc

3.2 ± 0.1 abc

0.033 ± 0.004 abc

0.00092 ± 0.00066 abc

259.63 ± 19.38 abc

4 Discussion

Fluorescent pseudomonad’s (FPs) are prevalent group of microorganism among plant rhizosphere associated bacteria. In recent days, FPs are eco-friendly weapons towards agricultally important plant pathogens, because of their antagonistic potential with abundance presence of antibiotic encoding genes and the secretion of plant growth promoting substance, hydrolytic enzymes and other antimicrobial traits (Shanmugaiah et al., 2006). In the present study focused on, biocontrol potential of phytopathogens, finger printing analysis and plant growth promoting potential of antagonistic FPs. Among 87 FPs, 34.4% (30) FPs were exhibited substantial antagonistic action towards R. solanacearum with different level of ZOI from 19 mm to 28 mm. In addition to that, 30 FPs were effectively control various phytopfungal pathogens from 6.3 mm to 30.7 mm compared to control (Table 2). Similarly, different researchers have also been documented that rhizospheric isolates have shown different levels of inhibition zone (ZOI) against various soil-borne fungal and bacterial pathogens, such as R. solanacearum, R. solani and F. oxysporum (Shanmugaiah et al., 2010; Elsayed et al., 2020). It has been documented that Pseudomonas spp is effective against a broad range of plant pathogens. Due to treatment of Pseudomonas spp against fungal pathogens indicated that, the remarkable morphological and physiological changes were take place in all tested fungal hyphae. The hyphal morphology and physical changes including disintegration, bulge, knotting, crumpling, destruction, contracting, bursting of mycelium and leakage of cytoplasm (Singh et al., 2016).

All the isolates of fluorescent pseudomonades were identified up to genus level by various physiological and biochemical analysis such as Grams reaction negative, shape of the all the isolates rod, indole, MR &VP negative, citrate utilization positive, catalase positive and oxidase positive (Table 3). In accordance with our results (Eladawy et al., 2020) reported that for identification of Pseudomonas spp based on their Grams’s reaction, shape, physiological and biochemical analysis. Moreover, the main characteristic future of Pseudomonas spp is pyocyanine pigments are presence on King’s B agar indicated that 100% comes under Pseudomonas spp (Nithya et al., 2019; Varatharaju et al., 2020).

There are various mechanism involved for the suppression fungal and bacterial pathogens by rhizosphere beneficial microbes. The prime mechanism is production of metabolites, hydrolytic enzyme, defense enzymes, hydrogen cyanide, siderophore and phosphate solubilization (Antoun and Kloepper, 2001; Harikrishnan et al., 2014; Nithya et al., 2019). In this context, from our study we assessed various hydrolytic enzymes of which, 20% amylase, 100% protease, 91% cellulose, 40% pectinase, 80% chitinase and 90% gelatinase was produced by our tomato rhizosphereric FPs (Table 4). Likewise, earlier research stated that FPs are generated by fungal cell wall degrading enzymes such as protease, cellulase and chitinase that are primarily involved for the control of phytopathogenic microbes and insects (Dunne et al., 1997).

Zhou et al. (2012) stated that Pseudomonas brassicacearum J12 was effectively control Ralstonia solanacearum by the production of protease. Hence, the assortment of rhizosphere isolates like B. subtilis, B. cereus, B. thuringiensis and Pseudomonas spp and many more rhizobacteria are possible to produce hydrolytic enzymes and metabolites to control phytopathogens like R. solani, F. oxysporum, S. rolfsii, P. ultimum etc. by swelling in the hyphae and at the hyphal tip, hyphal curling or bursting of the hyphal tip. The structural integrity of the cell wall of the targeted pathogens affects by hydrolytic enzymes produced by antagonistic microbes. In this view, biocontrol phase is more significant to inhibit phytopathogenes and makes them more important (Shanmugaiah et al., 2006; Jadhav and Sayyed, 2016). Interestingly, our potential antagonistic isolate Pseudomonas sp VSMKU3054 could produce all tested hydrolytic enzymes such protease, gelatinase, cellulase, amylase, chitinase and pectinase (Table 4). More recent research has shown that most of the antagonistic microbes are capable of degrading the fungal and bacterial cell membrane, cell membrane protein and regulate extracellular virulence factor of phytopathogens by antagonistic FPs due to the production of hydrolytic enzymes (Palaniyandi et al., 2013). The growth of R. solanacearum and development of wilt symptoms in tomatoes was arrested by the production of antimicrobial substance and hydrolytic enzymes like chitinase and glucanase related to substantial action and suppression of disease development by Bacillus thuringiensis (Elsharkawy et al., 2015).

Biocontrol potential against different phytopathogens by rhizobacterium Pseudomonas spp by the production of several secondary metabolites like Phenazine-1-carboxamide, 2,4-diacetylpholoroglucinol, pyrrolnitrin, pyoluteorin, siderophore, hydrogen cyanide, cell wall degrading enzymes and bio surfactants (Saikia et al., 2009; Shanmugaiah et al., 2010). The results were indicating in our isolates of Pseudomonas spp produced various metabolites like, siderophore (27), HCN (25), phosphate solubilization (30), indole acetic acid (23) compared to control (Table 4). In corroborate with our results, the production of Indole acetic acid (IAA), siderophore and phosphate solubilization evidently suggests a potential plant growth promoting ability of the isolates of Pseudomonas spp (Ayyadurai et al., 2006) and enhancement of growth and yield of canola, tomato, soybean and wheat (Cattelan et al., 1999). Moreover, our results of the in vitro study suggested that potential antagonistic isolate Pseudomonas sp VSMKU3054 with prominent inhibitory activity was the only isolate be able to produce siderophore, HCN, phosphate solubilization, indole acetic acid, antibiotic encoding genes and hydrolytic enzymes confirming the hypothesis of biocontrol (Kheirandish and Harighi, 2015). Hydrogen cyanide is a toxic gas capable of forming metal complexes with functional groups of different enzymes that inhibit processes such as CO2 and nitrate assimilation; disturbance of oxygen reduction in the respiratory cytochrome chain; and transport of electrons in photosynthesis by the way antagonistic microbes to control phytopathogens by the production may antimicrobial substance like HCN (Lanteigne et al., 2012). Kheirandish and Harighi, (2015) reported that different P. fluorescens could be linked to their production of plant growth stimulating substances that increase biomass production. (Lanteigne et al., 2012; Lemessa and Zeller, 2007) reported that plant biomass was significantly increased by strains of fluorescent pseudomonads. This may be the outcome of structural resistance induction, siderophore development and the competitive advantage of antagonist root colonization.

PGPR antagonistic to the pathogen must be tested and integrated as a biocontrol agent into effective disease management. The ability to adapt to the rhizosphere and actively colonize the host roots is a key characteristic of PGPR (Dunne et al., 1997). It was also proposed that they should be separated from various environments where they would be needed to work in order to achieve greater efficiency of biocontrol agents (Cook, 1993). R. solanacearum morphology and physiological function was regulated by the effectiveness of some of the naturally antagonistic isolates like Pseudomonas fluorescence, Bacillus spp and (Xue et al., 2009), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (Messiha et al., 2007), Streptomyces setonii (Lemessa and Zeller, 2007). A considerable amount of attention has been paid to the priority of the diversity of fluorescent pseudomonads to explore their biocontrol and biofertilization capabilities in recent scenarios (Naik et al., 2008; Saikia et al., 2011). In this context our results, among 16 distinct BOX-PCR prototypes two different clusters were find out with 60% and 40% similarity of Pseudomonas spp (Fig. 2a and b). Due to their high degree of genetic diversity, all our FPs isolates were shown different variations of fingerprinting patterns and distributed into different clusters.

Microbial diversity from rice and bean rhizosphere has been explored worldwide using a variety of molecular techniques (Koskey et al., 2018). Among different molecular tool, As a useful technique PCR-RFLP has been identified for the assessment of the genetic diversity of rhizobacteria among different groups of microorganisms (Moin et al., 2020; Nithya et al., 2020). Our results of DNA printing analysis showed that huge variation among the isolates of FPs. Among two major clusters, cluster 1 contained 90% of FPs, of which sub clad 2 consisting about 50% of FPs. whereas, the sub clad 1, 3, 4 and cluster 2 contain remaining of 50% FPs. Our finding specified that antagonistic FPs are highly diverse even 10 km distance and a single crop rhizosphere (Fig. 3a and b). Hence, the expression of genetic properties is greatly influenced by soil environment (Nowak-Thompson et al., 1994). Genetic variation was observed among FPs in our study, because of mutation, recombination and SOS response for release of DNA damage free radical by various metabolic reactions. Our research findings conformed that studies on diversity within a targeted bacterial population, to screen genotypes that are best adapted in a particular environmental stress or ecological habitat with our constrain objectives.

Antimicrobial compounds produced by FPs were involved for the control of various bacterial and fungal pathogens. Pseudomonas spp (Ayyadurai et al., 2007), P. aeruginosa MML2212 (Shanmugaiah et al., 2010), P. corrugate GFBP 5454 and P. mediterranea GFBP 5447 (Strano et al., 2017), Pseudomonas sp VSMKU4036 (Varatharaju et al., 2020), and P. aeruginosa VSMKU1 (Nithya et al., 2020) are significantly control the growth of different bacterial and fungal plant pathogens by the secretion of diffusible compounds like 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (2,4-DAPG), phenazine-1-carboxamide (PCN). In the present study, we detected 10 FPs obtained 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol encoding gene. Among 30 antagonistic FPs, 26 FPs and 12 FPs were observed the presence of hydrogen cyanide and pyoluteorin encoding gene with detection of specific size of the DNA along with their specific primers (Fig. 4b and c). Whereas none of the isolates FPs did not obtained pyrrolnitrin encoding gene isolated from tomato rhizosphere. Our result was concurrence with previous report for the production of 2,4-DAPG and PRN have been found to exist alone in one bacterium. However, Pseudomonas spp are rarely produced PLT antibiotics and no isolate has been obtained that only produces PLT (Liu et al., 2006). Pholoroglucinol assist and act as a signal molecule to induce the expression of pyrrolnitrin biosynthesis. P. fluorescence VSMKU3054 produced array of antimicrobial metabolites, and 2,4 diacetylphloroglucinol (2,4 DAPG) is a major encoding gene for the control of various plant pathogens. Moreover DAPG was effectively control R. solanacearum by in vitro. Guasp et al., (2000) demonstrated the 16 s rRNA is highly conserved primer binding sites and their gene sequences were hypervariable regions with high bacteria. The present study 16 s rRNA sequence compared with databases and identified as P. fluorescens with 98% similarity.

Based on the production of fluorescent pigments, rod shape, motile, catalase and oxidase and many carbon and nitrogen source utilization was positive by our isolate Pseudomonas sp VSMKU3054 and other various biochemical analysis were positive. After analysis of 16 s rDNA sequence analysis comparison with constructed phylogenetic tree, about 98% similarities coincide with that of Pseudomonas fluorescence (Fig. 5). Similar kind exercise done by Nithya et al., 2020.

Höfte et al. (1991) described that P. aeruginosa and B. cepacia enhanced seed germination and promoted plant growth. Pseudomonas sp MML2212 significantly enhances rice growth by the secretion of IAA (Shanmugaiah et al., 2006). Many rhizobial microbes like Trichoderma sp, Pseudomonas sp, Bacillus sp and Streptomyces sp VSMKU1014 are effectively enhance the growth of rice, cotton, green gram and sorghum (Harikrishnan et al., 2014; Mazrou et al., 2020). Similarly, our study has proven that, P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 remarkably enhance tomato seedling growth through remarkable increase of root and shoot length, fresh and dry weigh and vigor index compared to control (Table 5).

5 Conclusion

Our potential isolate P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 showed significant antagonism against phytopathogens. The isolate VSMKU3054 may prove the capacity to produce lytic enzymes and secondary metabolites. The effect of VSMKU3054 significantly enhance the seed germination of tomato seedlings. Hence, our isolate P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 could be used as a possible biocontrol agent for the management of soil borne plant pathogens.

Acknowledgements

The authors are greatly acknowledged UGC-BSR Meritorious Fellowship and DBT-IPLS Programme for financial support, New Delhi, India for the financial completion of this research work. All authors are grateful to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University Saudi Arabia for financial support through project No. RG-1441-504.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Biocontrol potential index of pseudomonads, instead of their direct-growth promotion traits, is a predictor of seed inoculation effect on crop productivity under field conditions. Biol. Control. 2020;143:104209.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of chrome azurol S reagents to evaluate siderophore production by rhizosphere bacteria. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 1991;12(1):39-45.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) Encyclopedia Genet. 2001:1477-1480.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) associated endophytic Pseudomonas putida BP25 alters root phenotype and induces defense in rice (Oryza sativa L.) against blast disease incited by Magnaporthe oryzae. Biol. Control. 2020;143:104181.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of a novel banana rhizosphere bacterium as fungal antagonist and microbial adjuvant in micropropagation of banana. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2006;100(5):926-937.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Functional characterization of antagonistic fluorescent pseudomonads associated with rhizospheric soil of rice (Oryza sativa L.) J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2007;17:919-927.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid in situ assay for indoleacetic acid production by bacteria immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 1991;57:535-538.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Screening for Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria to Promote Early Soybean Growth. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J.. 1999;63(6):1670-1680.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biocontrol efficiency of native plant growth promoting rhizobacteria against rhizome rot disease of turmeric. Biol. Control. 2019;129:55-64.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Making greater use of introduced microorganisms for biological control of plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol.. 1993;31(1):53-80.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The biocontrol agent Pseudomonas chlororaphis PA23 primes Brassica napus defenses through distinct gene networks. BMC Genom.. 2017;18:1-16.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biological control of Pythium ultimum by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia W81 is mediated by an extracellular proteolytic activity. Microbiology. 1997;143:3921-3931.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Lysozyme, Proteinase K, and Cephalosporins on Biofilm Formation by Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis.. 2020;2020:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biocontrol of Bacterial Wilt Disease through Complex Interaction between Tomato Plant, Antagonists, the Indigenous Rhizosphere Microbiota, and Ralstonia solanacearum. Front. Microbiol.. 2020;10:1-15.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Control of tomato bacterial wilt and root-knot diseases by Bacillus thuringiensis CR-371 and Streptomyces avermectinius NBRC14893. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci.. 2015;65(6):575-580.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rhizobacteria isolated from common bean in southern Italy as potential biocontrol agents against common bacterial blight. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.. 2016;144(2):297-309.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous Pseudomonas spp. Strains from the Olive (Olea europaea L.) rhizosphere as effective biocontrol agents against Verticillium dahliae: From the host roots to the bacterial genomes. Front. Microbiol.. 2018;9

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Utility of internally transcribed 16S–23S rDNA spacer regions for the definition of Pseudomonas stutzeri genomovars and other Pseudomonas species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.. 2000;50:1629-1639.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antagonistic potential of native strain Streptomyces aurantiogriseus VSMGT1014 against sheath blight of rice disease. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2014;30(12):3149-3161.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced production of phenazine-like metabolite produced by Streptomyces aurantiogriseus VSMGT1014 against rice pathogen. Rhizoctonia solani. J. Basic Microbiol.. 2016;56(2):153-161.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Seed protection and promotion of seedling emergence by the plant growth beneficial Pseudomonas Strains 7NSK2 and ANP15. Soil Biol. Biochem.. 1991;23(5):407-410.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic Diversity of Biocontrol Strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens Producing 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol from Southern India. J. Crop Improv.. 2012;26(2):228-243.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrolytic enzymes of rhizospheric microbes in crop protection. MOJ Cell Sci. Rep.. 2016;3:3-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of antifungal metabolite phenazine from rice rhizosphere fluorescent pseudomonads (FPs) and their effect on sheath blight of rice. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27(12):3313-3326.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, T., Rani, R., Manhas, R.K., 2019. Biocontrol and plant growth promoting potential of phylogenetically new Streptomyces sp. MR14 of rhizospheric origin. AMB Express 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0849-7.

- Conservation of the 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol biosynthesis locus among fluorescent Pseudomonas strains from diverse geographic locations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 1996;62:552-563.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of bacterial antagonists of Ralstonia solanacearum, causal agent of bacterial wilt of potato. Biol. Control. 2015;86:14-19.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J. Lab. Clin. Med.. 1954;44:301-307.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mode of action of microbial biological control agents against plant diseases: Relevance beyond efficacy. Front. Plant Sci.. 2019;10:1-19.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic characterization and diversity of Rhizobium isolated from root nodules of mid-altitude climbing bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) varieties. Front. Microbiol.. 2018;9:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Production of DAPG and HCN by Pseudomonas sp. LBUM300 contributes to the biological control of bacterial canker of tomato. Phytopathology. 2012;102(10):967-973.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Screening rhizobacteria for biological control of Ralstonia solanacearum in Ethiopia. Biol. Control. 2007;42(3):336-344.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic diversity of phenazine- and pyoluteorin-producing pseudomonads isolated from green pepper rhizosphere. Arch. Microbiol.. 2006;185(2):91-98.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Production of hydrocyanic acid by bacteria. Physiol. Plant.. 1948;1(2):142-146.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic diversity of phlD from 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. Phytopathology. 2001;91(1):35-43.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative molecular genetic diversity between Trichoderma spp. from Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2020;30(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: A new potential biocontrol agent of Ralstonia solanacearum, causal agent of potato brown rot. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.. 2007;118(3):211-225.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Managing the root rot disease of sunflower with endophytic fluorescent Pseudomonas associated with healthy plants. Crop Prot.. 2020;130:105066.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of genetic and functional diversity of phosphate solubilizing fluorescent pseudomonads isolated from rhizospheric soil. BMC Microbiol.. 2008;8:1-14.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plant Defence Related enzymes in Rice (Oryzae sativa L.), induced by Pseudomonas sp VsMKU2. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol.. 2019;13(3):1307-1315.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol by the biocontrol agent Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Can. J. Microbiol.. 1994;40(12):1064-1066.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extracellular proteases from Streptomyces phaeopurpureus ExPro138 inhibit spore adhesion, germination and appressorium formation in Colletotrichum coccodes. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2013;115(1):207-217.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Integrating biocontrol agents in strawberry powdery mildew control strategies in high tunnel growing systems. Crop Prot.. 2008;27(3-5):622-631.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mobilization of phosphorus in soil in connection with vital activity of some microbial species. Mikrobiologiya. 1948;17:362-370.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic production by bacterial biocontrol agents. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol.. 2002;81:537-547.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, characterization and evaluation of the biocontrol potential of Pseudomonas protegens RS-9 against Ralstonia solanacearum in Tomato. Indian J. Exp. Biol.. 2017;55:595-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacillus spp., a bio-control agent enhances the activity of antioxidant defense enzymes in rice against Pyricularia oryzae. PLoS One.. 2017;12(11):e0187412.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New primer generated bacterial mapping and biofertilizing potentiality assessment of Pseudomonas sp. isolated from cowdung. Int. J. Agron. Agric. Res.. 2014;5:2223-7054.

- [Google Scholar]

- Growth promotion of greenhouse tomatoes with Pseudomonas sp. and Bacillus sp. biofilms and planktonic cells. Appl. Soil Ecol.. 2019;138:61-68.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of mineral amendment on disease suppressive activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens to Fusarium wilt of chickpea. Microbiol. Res.. 2009;164(4):365-373.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic and functional diversity among the antagonistic potential fluorescent pseudomonads isolated from tea rhizosphere. Curr. Microbiol.. 2011;62(2):434-444.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Determination of antibiotic activity on plasmids from fluorescent pseudomonads isolates CW2, WB15 and WB52 against pre-emergence damping-off caused by Pythium ultimum and Rhizoctonia solani in cucumber. Biol. Control. 2010;53(2):161-167.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugaiah, V.; Ramesh, S.; Jayaprakashvel, M.; Mathivanan, N, Biocontrol and plant growth promoting potential of Pseudomonas sp. MML2212 from the rice rhizosphere. MITTEILUNGEN-BIOLOGISCHEN BUNDESANSTALT FUR LAND UND FORSTWIRTSCHAFT. 2006, pp. 408:320.

- Optimization of cultural conditions for production of chitinase by Bacillus laterosporous MML2270 isolated from rice rhizosphere soil. African J. Biotechnol.. 2008;7:2562-2568.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of single application of Trichoderma viride and Pseudomonas fluorescens on growth promotion in cotton plants. African J. Agric. Res.. 2009;4:1220-1225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Purification, crystal structure and antimicrobial activity of phenazine-1-carboxamide produced by a growth-promoting biocontrol bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa MML2212. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2010;108:703-711.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biocontrol mechanisms of siderophores against bacterial plant pathogens sustain. Approaches to control. Plant Pathog. Bact.. 2015;167–190

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bio-protective microbial agents from rhizosphere eco-systems trigger plant defense responses provide protection against sheath blight disease in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Microbiol. Res.. 2016;192:300-312.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pseudomonas fluorescens mediated systemic resistance in tomato is driven through an elevated synthesis of defense enzymes. Biol. Plant.. 2011;55(2):317-322.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biocontrol properties and functional characterization of rice rhizobacterium pseudomonas sp. VsMKU4036. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol.. 2020;14(2):1545-1556.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant root exudates are involved in Bacillus cereusAR156 mediated biocontrol against Ralstonia solanacearum. Front. Microbiol.. 2019;10:1-14.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The ACC deaminase expressing endophyte Pseudomonas spp. Enhances NaCl stress tolerance by reducing stress-related ethylene production, resulting in improved growth, photosynthetic performance, and ionic balance in tomato plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2018;127:599-607.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rhizocompetence and antagonistic activity towards genetically diverse Ralstonia solanacearum strains - An improved strategy for selecting biocontrol agents. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2013;97(3):1361-1371.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of Pseudomonas brassicacearum J12 as an antagonist against Ralstonia solanacearum and identification of its antimicrobial components. Microbiol. Res.. 2012;167(7):388-394.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]