Translate this page into:

First detection of Nosema sp., microsporidian parasites of honeybees (Apis mellifera) in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia

⁎Corresponding author at: Zoology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, 11451 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Tel.: +966 14675754; fax: +966 14678514. azema1@yahoo.com (Abdel-Azeem S. Abdel-Baki)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Nosema sp. is recorded in Saudi Arabia for the first time, in adult Apis mellifera collected from apiaries in Riyadh city. Samples of 100 workers were collected and examined for the infection with Nosema sp. 5% of the bees were found positively infected with Nosema sp. Spores were oval to elliptical shaped and measuring 6.4 (5.0–7.0) μm in length, 3.4 (3.0–4.5) μm in width. The conclusive identification of the present Nosema species will preclude until further ultrastructure and molecular studies. The present study concluded that intensive surveys are prerequisite to identify the species of Nosema and to estimate their distribution and prevalence in different regions of Saudi Arabia.

Keywords

Parasite

Microsporidia

Nosemosis

Bee

1 Introduction

Honey bees play a substantial role in the environment by pollinating wild flowers and agricultural crops as they forage for nectar and pollen, as well as manufacturing honey and beeswax. Beekeeping in Saudi Arabia is a growing business; indeed, Saudi Arabia is the third biggest producer of honey in the Middle East with an estimated 4000 beekeepers and 700,000 bee hives, providing a total of about 3500 tons of honey per year (Alqarni et al., 2011; Alattal et al., 2014). The fundamental and beneficial activities of bees depend on beekeepers safeguarding a healthy population of honey bees, because, like other insects and livestock, honey bees are subject to a range of diseases and pests. Nosemosis is one of the most widespread diseases affecting honey bees worldwide and it is caused by two distinct species of unicellular microsporidian parasites, Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae (e.g., Farrar (1947), Weiser (1961), Moeller (1978), Liu (1984), Fries (1988), Charbonneau et al. (2016)). N. apis was isolated in the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) (Zander, 1909) and N. ceranae was isolated from the Asian honey bee (Apis cerana) in China (Fries et al., 1996). In essence, however, both species have an essentially global distribution and the two species can co-infect honey bees (Chen et al., 2009; Burgher-MacLellan et al., 2010; Charbonneau et al., 2016). It has been proven, however, that the epidemiological pattern and pathology of N. ceranae and N. apis are different and therefore, now, the disease caused by N. ceranae is named nosemosis type C while that caused by N. apis is known as “nosemosis type A” (COLOSS workshop, 2009).

The symptoms of infection by N. apis are easy to recognize; there are large numbers of dead bees within the colony and diarrhea stains at entrances of hive indicating gastrointestinal disorders (Bourgeois et al., 2010; Araneda et al., 2015). By contrast, the symptoms of nosemosis caused by N. ceranae are less apparent; the growth of colonies grow is weak producing significant reductions in colony size and it is possible to detect the disease throughout the entire year (Bourgeois et al., 2010; Higes et al., 2010; Araneda et al., 2015). The prevalence of nosemosis disease has been proven to vary among regions and years (Mulholland et al., 2012). Although, N. apis has a world-wide distribution it is not considered an important problem in tropical and sub-tropical regions (Wilson and Nunamaker, 1983). However, in temperate regions N. apis infections typically peak in the spring, decrease during the summer and then increase again in the fall before declining during the early winter months (Higes et al., 2010). On the other hand, N. ceranae show less seasonality and can be detected in all four seasons (Higes et al., 2010).

Symptoms of nosemosis have been reported before among honey bees in Saudi Arabia (e.g. Al Ghamdi (1990), Alattal and Al Ghamdi (2015)), but the presence of Nosema spores themselves has not yet been described.

In the present brief study we report for the first time the presence of Nosema spores in honey bees in Saudi Arabia.

2 Materials and methods

One hundred honey bee workers (A. mellifera) were collected from five apiaries in Riyadh city (twenty from each apiary) and examined one by one for the presence of any microsporidian spores following the method adapted by Bollan et al. (2013). Briefly, the abdomen of honeybees was isolated from their bodies, squashed, homogenized employing a mortar and pestle and resuspended in distilled water (1 ml water/bee). Then, a few drops of the suspension were placed on the slides and examined under a microscope at a magnification of 400×, to detect any Nosema spore. Photographic documentation and spore measurements were performed using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with an Olympus DP71 camera (Olympus, Japan). Measurements are presented in micrometers and data are expressed as the mean followed by the range in parentheses.

3 Results

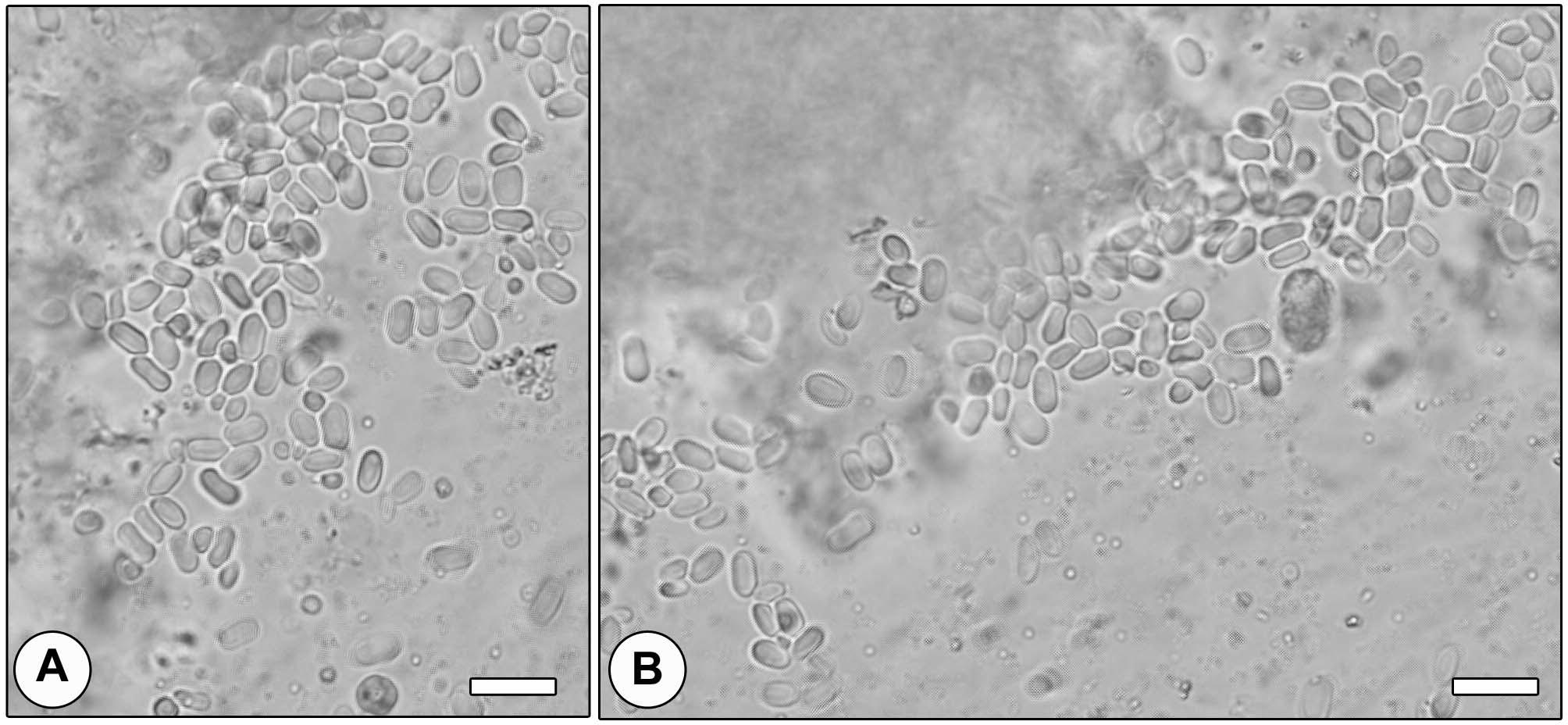

Of 100 honey bees workers (A. mellifera) examined for the infection with Nosema spp., five were found infected. The five infected workers are from two different apiaries (3 from one and 2 from the other). Light microscopic examination of the midgut content and fecal matter revealed the presence of huge numbers of microsporidian spores. Spores were oval to elliptical shaped and varied in size, measuring 6.4 (5.0–7.0) μm in length and 3.4 (3.0–4.5) μm in width (N = 50) (Fig. 1).

Fresh spores of Nosema sp. infected the gut of bee (Apis mellifera) collected from different apiaries in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia. Scale-bar = 10 μm.

4 Discussion

Nosemosis is a bee disease caused by spore-forming parasites of the genus Nosema, which attack the epithelial lining of the middle intestine of the worker bees, queens and drones (Botías et al., 2012; Bollan et al., 2013). For a long time, the only known causative agent of Nosemosis in honeybees (A. mellifera) was the unicellular microsporidium N. apis (Nabian et al., 2011). Later, Higes et al. (2006) reported a new microsporidium, N. ceranae, as the main motive agent of nosemosis in Spain. Shortly after, the presence of N. ceranae was confirmed in Europe, America, and Asia (Chen et al., 2008; Chen and Huang, 2010; Nabian et al., 2011). Recent prevalence studies indicate that infections with N. apis and N. ceranae can co-occur and be present as mixed infections in both Europe and North America (Copley et al., 2012; Milbrath et al., 2015). Recently, Eiri et al. (2015) proved that N. ceranae can infect honey bee larvae and decrease subsequent adult longevity. It has been postulated that N. ceranae is more predominant in warmer countries compared to N. apis (Nabian et al., 2011; Haddad, 2014; Van der Zee et al., 2014). It seems that N. ceranae is better acclimatized to complete its endogenous cycle with a higher biotic index at different temperatures reflecting greater incidence of the disease in warmer regions and the epidemiological differences between both Nosema species in field conditions and at the colony level (Martín-Hernández et al., 2007, 2009).

Commonly, spore measurements of N. apis are larger than those of N. ceranae (Chen and Huang, 2010). In the present study the average spore size of the identified Nosema sp. was 6.4 × 3.4 μm, which is very close to the average spore size of N. apis, reported by Fries et al. (1996) as 6.0 × 3.0 μm, but quite distinct from the average N. ceranae spore size of 4.4 × 2.2 μm (Chen et al., 2009). At the ultrastructural level, on the other hand, the number of polar filament coils inside N. ceranae spores was 18–21 compared to more than 30 coils inside N. apis (Fries, 1989; Chen et al., 2009). This reiterates that it is only possible to arrive at robust differential diagnosis and classification of N. apis and of N. ceranae by combining morphological and molecular data (Bollan et al., 2013). The conclusive identification of the species of the present Nosema therefore awaits further ultrastructural and molecular studies. Accordingly, the present parasite will be allocated simply as Nosema sp.

Although some passing references in the literature can be found to Nosemosis in Saudi Arabia (e.g. Al Ghamdi (1990), Alattal and Al Ghamdi (2015)), this report describes systematically for the first time the spores of Nosema sp. in colonies of A. mellifera in Saudi Arabia. There is now a clear need for intensive surveys to identify the species of Nosema, and to determine their distribution and prevalence in different regions of Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgement

We extend our appreciation to the Dean of Scientific Research, King Saud University, for funding the work through the research group project no. PRG-1436-02.

References

- Impact of temperature extremes on survival of indigenous and exotic honey bee subspecies, Apis mellifera, under desert and semiarid climates. Bull. Insectol.. 2015;68:219-222.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of the native honey bee subspecies in Saudi Arabia using the mtDNA COI–COII intergenic region and morphometric characteristics. Bull. Insectol.. 2014;67:31-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey of Honeybee Diseases, Pests and Predators in Saudi Arabia. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales; 1990. (M. Phil Thesis)

- The indigenous honey bees of Saudi Arabia (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Apis mellifera jemenitica Ruttner): their natural history and role in beekeeping. ZooKeys. 2011;134:83-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution, epidemiological characteristics and control methods of the pathogen Nosema ceranae Fries in honey bees Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera, Apidae) Arch. Med. Vet.. 2015;47:129-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- The microsporidian parasites Nosema ceranae and Nosema apis are widespread in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies across Scotland. Parasitol. Res.. 2013;112:751-759.

- [Google Scholar]

- Critical aspects of the Nosema spp. diagnostic sampling in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies. Parasitol. Res.. 2012;110:2557-2561.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic detection and quantification of Nosema apis and N. ceranae in the honey bee. J. Invertebr. Pathol.. 2010;103:53-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of duplex real-time PCR with melting-curve analysis for detecting the microsporidian parasites Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae in Apis mellifera. Can. Ent.. 2010;142:271-283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Nosema apis, N. ceranae, and coinfections on honey bee (Apis mellifera) learning and memory. Sci Rep.. 2016;6:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosema ceranae is a long present and wide-spread microsporidian infection of the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) in the United States. J. Invertebr. Pathol.. 2008;97:186-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asymmetrical coexistence of Nosema ceranae and Nosema apis in honeybees. J. Invertebr. Pathol.. 2009;101:204-209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosema ceranae, a newly identified pathogen of Apis mellifera in the U.S. and Asia. Apidologie. 2010;41:364-374.

- [Google Scholar]

- COLOSS Workshop, 2009. Nosema disease: Lack of knowledge and work standardization. FA 0803: 1–39.

- Prevalence and seasonality of Nosema species in Québec honey bees. Can. Entomol.. 2012;144:577-588.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosema ceranae can infect honey bee larvae and reduces subsequent adult longevity. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126330.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosema losses in package bees as related to queen supersedure and honey yields. J. Econ. Entomol.. 1947;40:333-338.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infectivity and multiplication of Nosema apis Z. in the ventriculus of the honey bee. Apidologie. 1988;19:319-328.

- [Google Scholar]

- Observations on the development and transmission of Nosema apis Z. in the ventriculus of the honey bee. J. Apicult. Res.. 1989;28:107-117.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosema ceranae n. sp. (Microspora, Nosematidae), morphological and molecular characterization of a microsporidian parasite of the Asian honey bee Apis cerana (Hymenoptera, Apidae) Eur. J. Protistol.. 1996;32:356-365.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosema ceranae, a new microsporidian parasite in honey bees in Europe. J. Invertebrate Pathol.. 2006;92:93-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosema ceranae in Europe: an emergent type C nosemosis. Apidologie. 2010;41:375-392.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrastructure of the midgut of the worker honey bee Apis mellifera heavily infected with Nosema apis. J. Invertebr. Pathol.. 1984;44:282-291.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature on the biotic potential of honeybee microsporidia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2009;75:2554-2557.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of colonization of Apis mellifera by Nosema ceranae. Appl Environ. Microbiol.. 2007;73:6331-6338.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative virulence and competition between Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae in honey bees (Apis mellifera) J. Invertebr. Pathol.. 2015;125:9-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, F.E., 1978. Nosema disease. Its control in honey bee colonies. Department of Agriculture, Washington D.C.N.S. Bulletin No. 1569, 16 pp.

- Individual variability of Nosema ceranae infections in Apis mellifera colonies. Insects. 2012;3:1143-1155.

- [Google Scholar]

- First detection of Nosema ceranae, a microsporidian protozoa of European honeybees (Apis mellifera) in Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol.. 2011;6:89-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Virulence and polar tube protein genetic diversity of Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia) field isolates from Northern and Southern Europe in honeybees (Apis mellifera iberiensis) Environ. Microbiol. Rep.. 2014;6:401-413.

- [Google Scholar]

- Die Mikrosporidien als Parasiten der Insekten. Monogr. Angew. Entomol.. 1961;17:1-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tierische Parasiten als Krankenheitserreger bei der Biene. Münch. Bienenztg.. 1909;31:196-204.

- [Google Scholar]