Translate this page into:

Estimation methods for the discrete Poisson-Lindley and discrete Lindley distributions with actuarial measures and applications in medicine

⁎Corresponding author. ahmed.afify@fcom.bu.edu.eg (Ahmed Z. Afify)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Discrete distributions have their important in modeling count data in several applied fields such as epidemiology, public health, sociology, medicine, and agriculture. This paper discusses the estimation of the parameters of two discrete models called discrete Poisson-Lindley and discrete Lindley distributions, using several frequentist estimation methods. Parameter estimation can provide a guideline for choosing the best method of estimation for the model parameters, which would be very important to reliability engineers and applied statisticians. The finite sample properties of the estimates are explored using extensive simulation results. The ordering performance of the proposed estimators is determined by the partial and overall ranks of different parametric values. We also derived two important actuarial measures of the two discrete models. A computational study for the two risk measures is conducted. Finally, applications of the two discrete distributions have been examined and compared with other discrete distributions via three data sets from the medicine field including two COVID-19 data sets.

Keywords

Bootstrap confidence intervals

COVID-19 data

Discrete-Lindley distribution

Discrete Poisson-Lindley distribution

Percentile estimation

TVaR

1 Introduction

The discrete distributions are very useful in modeling count data in several applied fields such as medicine, public health, epidemiology, agriculture, sociology, and applied science. Many discrete distributions have been proposed for modeling count data. However, the traditional discrete distributions including geometric and Poisson have limited applicability as models for failure times, reliability, counts, etc. This is so, since many real count data show either under-dispersion, in which the variance is smaller than the mean or over-dispersion, in which the variance is greater than the mean. This has motivated many authors to develop some new discrete distributions based on classical continuous distributions for failure times, reliability, etc.

Sankaran (1970) introduced the discrete Poisson-Lindley (DPL) distribution which is specified by the probability mass function (PMF)

Bakouch et al. (2014) proposed the discrete Lindley (DL) distribution as a discrete version of the continuous Lindley distribution. The PMF of the DL distribution takes the form

Our aim in this paper is to explore the estimation of the DPL and DL parameters by five methods of estimation, such as the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE), Cramér-von Mises estimator (CVME), least-square estimator (OLSE), weighted least squares estimator (WLSE) and percentile estimator (PCE). We compare the proposed estimators using an extensive computational simulations to develop a guideline for choosing the best estimation method that provides better estimates for the parameters of the DPL and DL models.

In this regard, comparing several frequentist estimators for estimating the parameters of different continuous distributions are conducted by several authors. Notable among them are Dey et al. (2017), Nassar et al. (2018), Rodrigues et al. (2018), Afify and Mohamed (2020), Shakhatreh et al. (2020), Afify et al. (2020), Al-Mofleh et al. (2020), Aldahlan and Afify (2020) and Nassar et al. (2020) for exponentiated-Gumbel, transmuted exponentiated Pareto, Poisson-exponential, extended odd Weibull exponential, generalized extended exponential Weibull, generalized Ramos-Louzada, exponentiated half-logistic exponential and alpha power-exponential distributions.

As far as we know, there are no reports on estimation of parameters of the DPL and DL distribution based on several frequentist estimators. To the best of our knowledge, Sankaran (1970) proposed the moments and maximum likelihood methods for estimating the DPL parameter. However, he only used the moments estimator for the two analyzed data sets he studied. Ghitany and Al-Mutairi (2009) presented a simulation study to compare the moments and maximum likelihood estimators and showed that the two estimators are consistent and asymptotically normal.

Further, we derive two important risk measures for the DPL and DL distributions, called value at risk and tail value at risk which are useful in evaluating the exposure to market risk in a portfolio of instruments. The numerical simulations of the two risk measures are presented for the two discrete distributions using several parametric values.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we derive the value at risk and tail value at risk for the DPL and DL distributions along with detailed numerical simulations for these measures. In Section 3, different classical methods of parameter estimation are discussed. In Section 4, we present the simulation results to compare and assess the performance of the proposed estimators. Three COVID-19 data sets are analyzed to validate the use of DPL and DL distributions in fitting lifetime count data are explored in Section 5. Finally, concluding remarks are presented in Section 6.

2 Actuarial measures

In this section, we determine the value at risk (VaR) and tail value at risk (TVaR) for the DPL and DL distributions, which play a crucial role in portfolio optimization under uncertainty.

2.1 VaR measure

The VaR of any random variable X is the quantile of its CDF as shown in Artzner (1999), and it is defined, for a probability level , by .

The VaR of the DPL distribution with PMF (1) is derived as The VaR of the DL model with PMF (5) takes the form

2.2 TVaR Measure

The TVaR is an important actuarial measure, and it is used to determine the expected value of the loss given that an event outside a given probability level has occurred. The TVaR is defined in Klugman et al. (2012) by the following equation Using Eqs. (3) and (4), the TVaR of the DPL distribution is derived as Similarly, based on Eqs. (7) and (8), the TVaR of the DL distribution follows as

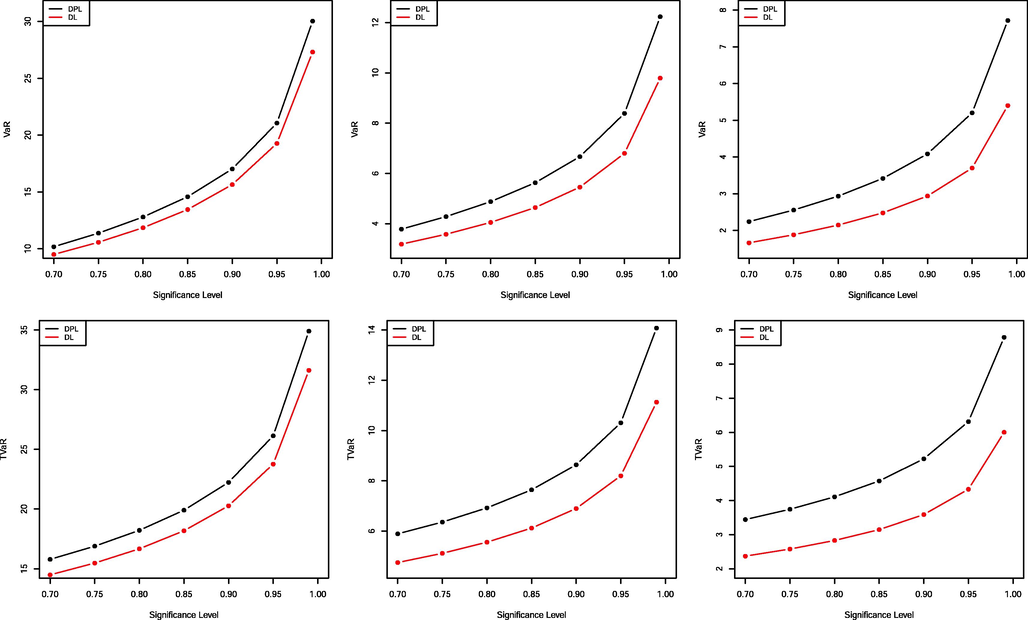

2.3 Simulations for risk measures

In this sub-section, we present some numerical computations for the VaR and TVaR measures of the DPL and DL distributions for different parametric values. The results can be obtained as follows.

-

A random sample of size is generated from the DPL and DL distributions and their parameters are estimated by the maximum likelihood method.

-

The VaR and TVaR of the two distributions are calculated from 2,000 repetitions.

| Significance Level | DPL( ) | DL( ) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.70 | 8.90197 | 8.26617 |

| 0.75 | 9.95805 | 9.2078 |

| 0.80 | 11.21761 | 10.32968 |

| 0.85 | 12.79907 | 11.73696 |

| 0.90 | 14.96585 | 13.66341 |

| 0.95 | 18.5491 | 16.84654 |

| 0.99 | 26.50909 | 23.91149 |

| Significance Level | DPL( ) | DL( ) |

| 0.70 | 4.03788 | 3.50114 |

| 0.75 | 4.56447 | 3.9304 |

| 0.80 | 5.19558 | 4.44301 |

| 0.85 | 5.99151 | 5.08736 |

| 0.90 | 7.08663 | 5.97111 |

| 0.95 | 8.90529 | 7.43411 |

| 0.99 | 12.96347 | 10.68758 |

| Significance Level | DPL( ) | DL( ) |

| 0.70 | 1.02010 | 0.51384 |

| 0.75 | 1.17239 | 0.58836 |

| 0.80 | 1.35813 | 0.67874 |

| 0.85 | 1.59661 | 0.79409 |

| 0.90 | 1.93101 | 0.95472 |

| 0.95 | 2.49861 | 1.22504 |

| 0.99 | 3.8006 | 1.83774 |

| Significance Level | DPL( ) | DL( ) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.70 | 13.81718 | 12.58693 |

| 0.75 | 14.79489 | 13.45659 |

| 0.80 | 15.97354 | 14.50447 |

| 0.85 | 17.46878 | 15.83318 |

| 0.90 | 19.53854 | 17.67156 |

| 0.95 | 22.99892 | 20.74363 |

| 0.99 | 30.78289 | 27.65028 |

| Significance Level | DPL( ) | DL( ) |

| 0.70 | 6.28894 | 5.23761 |

| 0.75 | 6.78275 | 5.63693 |

| 0.80 | 7.37937 | 6.11848 |

| 0.85 | 8.13786 | 6.72957 |

| 0.90 | 9.19001 | 7.57572 |

| 0.95 | 10.9531 | 8.99085 |

| 0.99 | 14.92949 | 12.17532 |

| Significance Level | DPL( ) | DL( ) |

| 0.70 | 1.44267 | 0.59833 |

| 0.75 | 1.59315 | 0.67166 |

| 0.80 | 1.7768 | 0.76072 |

| 0.85 | 2.01277 | 0.87453 |

| 0.90 | 2.34394 | 1.03330 |

| 0.95 | 2.90669 | 1.30100 |

| 0.99 | 4.1999 | 1.90943 |

- Plots of the VaR (top panel) and TVaR (bottom panel) of the DPL and DL distributions using the values in Tables 1 and 2.

The results in Tables 1 and 2 and the plots in Fig. 1 reveal that the VaR and TVaR measures are increasing functions in the parameter , for the DPL distribution, and , for the DL distribution.

3 Estimation methods

In this section, we discuss the estimation of the parameters of the DPL and DL distributions using several classical methods of estimation including the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE), Cramér-von Mises estimator (CVE), least-squares estimator (LSE), weighted least squares estimator (WLSE) and percentile estimator (PCE).

3.1 Maximum likelihood estimation

Let

be a random sample of size n from the DPL model with PMF (2), then the log-likelihood function reduces to

Let

be a random sample of size n from the DL model with PMF (5), then the log-likelihood function is given by

3.2 Least-squares and weighted least-squares estimation

Let

be the order statistics from the DPL distribution. By minimizing the following equation, we have LSE (Swain et al., 1988) of the parameter

of the DPL distribution

it can be also obtained by solving the following non-linear equation

where

Let

be the order statistics of a random sample from the DL distribution. The LSE of the DL parameter

follows by minimizing the following equation with respect to

The LSE of

can also be obtained by solving the following non-linear equation

where

3.3 Cramér-von Mises Estimation

The CVME of the parameter of the DPL distribution is obtained by minimizing the following equation or by solving the following non-linear equation where is defined in Eq. (13). Further details about the CVME can be explored in Macdonald (1971) and Luceño (2006). The CVME of the DL parameter can be calculated by minimizing the following equation or by solving the following non-linear equation where is given in Eq. (14).

3.4 Percentile Estimation

This estimation method was introduced by Kao (1958, 1959). Let be an estimate of , then the PCE of DPL parameter follows by minimizing where We can also obtain the PCE of the parameter by solving the following non-linear equation where Let is an estimate of , then the PCE of the DL parameter follows by minimizing The PCE of the parameter can also be determined by solving the non-linear equation where

4 Simulation Study

In this section, the performance of different estimation methods for estimating the DPL( ) and DL( ) parameters is explored via numerical simulations. Different sample sizes, , and several parametric values are considered for the parameters and . We generate random samples from the two distributions using Eqs. (3) and (7), respectively. The performance of these estimators are assessed by determining some indices such as the average values of the estimates (AVEs), average mean square errors (MSEs), average absolute biases (ABBs), and average mean relative estimates (MREs) for all sample sizes and parametric combinations using the R software©.

These indices can be determined using the following equations where or .

Simulation results including AVEs, ABBs, MSEs and MREs for the two parameters

and

of the DPL and DL distributions using several estimation approaches are reported in Tables 3–6. Additionally, these tables illustrate the rank of each estimator among all the five estimators which is represented by superscript indicators in each row and the

which is represented by the partial sum of ranks in each column for every sample size.

n

Est.

MLE

CVME

LSE

PCE

WLSE

20

AVEs

0.19606

0.20512

0.20529

0.19537

0.20363

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

40

AVEs

0.19276

0.20266

0.20228

0.19585

0.20133

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

60

AVEs

0.19162

0.20134

0.20073

0.19573

0.20103

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

80

AVEs

0.19137

0.20129

0.20019

0.19652

0.20056

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

100

AVEs

0.19106

0.20086

0.20045

0.19704

0.20071

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

20

AVEs

0.45460

0.51588

0.50524

0.48614

0.50106

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

40

AVEs

0.44802

0.50510

0.50127

0.48845

0.50064

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

60

AVEs

0.44914

0.49937

0.49984

0.48864

0.49723

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

80

AVEs

0.44615

0.50067

0.50012

0.48867

0.49659

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

100

AVEs

0.44547

0.49984

0.49761

0.49103

0.49653

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

n

Est.

MLE

CVME

LSE

PCE

WLSE

20

AVEs

0.82634

1.00301

0.98853

0.39414

0.98526

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

40

AVEs

0.81185

0.98221

0.97546

0.39857

0.97555

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

60

AVEs

0.80381

0.97510

0.97837

0.40102

0.97408

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

80

AVEs

0.80129

0.96981

0.97179

0.40182

0.97040

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

100

AVEs

0.80080

0.97775

0.96876

0.40777

0.97156

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

20

AVEs

1.13242

1.45882

1.42722

1.47038

1.43834

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

40

AVEs

1.10559

1.41598

1.40194

1.47368

1.43224

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

60

AVEs

1.09942

1.40902

1.40520

1.46148

1.43142

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

80

AVEs

1.09837

1.40565

1.40449

1.46497

1.41964

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

100

AVEs

1.09223

1.39648

1.39322

1.47211

1.42241

ABBs

MSEs

MREs

Ranks

n

Est.

MLE

CVME

LSE

PCE

WLSE

20

AVEs

0.20428

0.21867

0.21764

0.19561

0.21647

ABBs

0.02624{1}

0.03455{4}

0.03515{5}

0.02759{2}

0.03290{3}

MSEs

0.00113{1}

0.45543{5}

0.00224{3}

0.00117{2}

0.00662{4}

MREs

0.13122{1}

0.17276{4}

0.17576{5}

0.13794{3}

0.16450{2}

Ranks

40

AVEs

0.20179

0.21546

0.21517

0.19499

0.21510

ABBs

0.01819{1}

0.02512{5}

0.02509{4}

0.01912{2}

0.02470{3}

MSEs

0.00054{1}

0.44796{5}

0.00111{3}

0.00057{2}

0.00489{4}

MREs

0.09097{1}

0.12561{5}

0.12543{4}

0.09560{2}

0.12348{3}

Ranks

60

AVEs

0.20131

0.21501

0.21413

0.19588

0.21386

ABBs

0.01507{1}

0.02128{4}

0.02150{5}

0.01566{2}

0.02058{3}

MSEs

0.00036{1}

0.44746{5}

0.00076{3}

0.00037{2}

0.00416{4}

MREs

0.07537{1}

0.10641{4}

0.10748{5}

0.07832{2}

0.10290{3}

Ranks

80

AVEs

0.20195

0.21412

0.21352

0.19634

1.41964

ABBs

0.01258{1}

0.01948{4}

0.01927{3}

0.01344{2}

0.21311{5}

MSEs

0.00026{1}

0.44678{5}

0.00060{3}

0.00028{2}

0.01814{4}

MREs

0.06291{2}

0.09740{5}

0.09633{4}

0.06718{3}

0.00393{1}

Ranks

100

AVEs

0.20061

0.21319

0.21407

0.19668

0.21336

ABBs

0.01161{1}

0.01757{4}

0.01809{5}

0.01189{2}

0.01713{3}

MSEs

0.00021{1}

0.44578{5}

0.00051{3}

0.00023{2}

0.00376{4}

MREs

0.05804{1}

0.08784{4}

0.09044{5}

0.05943{2}

0.08563{3}

Ranks

20

AVEs

0.45543

0.50757

0.50711

0.48569

0.50300

ABBs

0.06791{2}

0.07239{4}

0.07257{5}

0.06734{1}

0.06946{3}

MSEs

0.00662{1}

0.00900{5}

0.00897{4}

0.00723{2}

0.00795{3}

MREs

0.13582{2}

0.14478{4}

0.14514{5}

0.13468{1}

0.13892{3}

Ranks

40

AVEs

0.44796

0.50448

0.50012

0.48775

0.49911

ABBs

0.05983{5}

0.05015{4}

0.05004{3}

0.04821{1}

0.04852{2}

MSEs

0.00489{5}

0.00414{4}

0.00397{3}

0.00360{1}

0.00371{2}

MREs

0.11966{5}

0.10030{4}

0.10008{3}

0.09643{1}

0.09704{2}

Ranks

60

AVEs

0.44746

0.49718

0.50018

0.48812

0.49580

ABBs

0.05631{5}

0.03982{2}

0.04011{3}

0.04035{4}

0.03790{1}

MSEs

0.00416{5}

0.00250{2}

0.00257{4}

0.00253{3}

0.00227{1}

MREs

0.11263{5}

0.07963{2}

0.08021{3}

0.08069{4}

0.07580{1}

Ranks

80

AVEs

0.44678

0.49888

0.49745

0.49242

0.49762

ABBs

0.05524{5}

0.03556{3}

0.03569{4}

0.03517{2}

0.03347{1}

MSEs

0.00393{5}

0.00196{3}

0.00200{4}

0.00191{2}

0.00176{1}

MREs

0.11048{5}

0.07111{3}

0.07138{4}

0.07035{2}

0.06694{1}

Ranks

100

AVEs

0.44578

0.49805

0.49762

0.49246

0.49460

ABBs

0.05516{5}

0.03122{2}

0.03192{4}

0.03160{3}

0.02976{1}

MSEs

0.00376{5}

0.00153{2}

0.00161{4}

0.00154{3}

0.00141{1}

MREs

0.11033{5}

0.06245{2}

0.06385{4}

0.06319{3}

0.05952{1}

Ranks

n

Est.

MLE

CVME

LSE

PCE

WLSE

20

AVEs

0.82182

0.97809

0.96423

0.38079

0.97326

ABBs

0.19066{5}

0.13673{2}

0.13624{1}

0.14081{4}

0.13880{3}

MSEs

0.04606{4}

1.12290{5}

0.02838{1}

0.03222{3}

0.03047{2}

MREs

0.19066{5}

0.13673{2}

0.13624{1}

0.14081{4}

0.13880{3}

Ranks

40

AVEs

0.80929

0.96822

0.96475

0.38904

0.96779

ABBs

0.19194{5}

0.09707{1}

0.09854{2}

0.10242{3}

0.10261{4}

MSEs

0.04282{4}

1.11120{5}

0.01488{1}

0.01615{3}

0.01603{2}

MREs

0.19194{5}

0.09707{1}

0.09854{2}

0.10242{3}

0.10261{4}

Ranks

60

AVEs

0.80397

0.96037

0.96231

0.39034

0.96423

ABBs

0.19624{5}

0.08432{4}

0.08163{1}

0.08230{2}

0.08331{3}

MSEs

0.04263{4}

1.10966{5}

0.01014{1}

0.01056{2}

0.01059{3}

MREs

0.19624{5}

0.08432{4}

0.08163{1}

0.08230{2}

0.08331{3}

Ranks

80

AVEs

0.80331

0.96340

0.95640

0.39368

0.96558

ABBs

0.19673{5}

0.07436{3}

0.07544{4}

0.07339{2}

0.07205{1}

MSEs

0.04193{4}

1.10632{5}

0.00847{3}

0.00828{2}

0.00789{1}

MREs

0.19673{5}

0.07436{3}

0.07544{4}

0.07339{2}

0.07205{1}

Ranks

100

AVEs

0.80240

0.96210

0.95805

0.39654

0.96737

ABBs

0.19760{5}

0.06718{3}

0.06812{4}

0.06577{1}

0.06624{2}

MSEs

0.04160{4}

1.10346{5}

0.00699{3}

0.00664{2}

0.00663{1}

MREs

0.19760{5}

0.06718{3}

0.06812{4}

0.06577{1}

0.06624{2}

Ranks

20

AVEs

1.12290

1.38100

1.36864

1.46240

1.40862

ABBs

0.38079{5}

0.21436{3}

0.21037{1}

0.23352{4}

0.21259{2}

MSEs

0.16817{5}

0.06645{2}

0.06416{1}

0.08795{4}

0.06797{3}

MREs

0.25386{5}

0.14290{3}

0.14025{1}

0.15568{4}

0.14173{2}

Ranks

40

AVEs

1.11120

1.36654

1.36327

1.46978

1.41346

ABBs

0.38904{5}

0.17306{3}

0.17496{4}

0.16748{2}

0.16515{1}

MSEs

0.16322{5}

0.04279{3}

0.04275{2}

0.04293{4}

0.04105{1}

MREs

0.25936{5}

0.11537{3}

0.11664{4}

0.11165{2}

0.11010{1}

Ranks

60

AVEs

1.10966

1.36881

1.36059

1.47028

1.41498

ABBs

0.39034{5}

0.15704{3}

0.15872{4}

0.13801{1}

0.14123{2}

MSEs

0.16099{5}

0.03448{3}

0.03479{4}

0.02881{1}

0.02943{2}

MREs

0.26023{5}

0.10469{3}

0.10581{4}

0.09201{1}

0.09415{2}

Ranks

80

AVEs

1.10632

1.36635

1.36064

1.47588

1.41368

ABBs

0.39368{5}

0.14766{3}

0.15346{4}

0.11639{1}

0.12443{2}

MSEs

0.16079{5}

0.02978{3}

0.03201{4}

0.02114{1}

0.02258{2}

MREs

0.26245{5}

0.09844{3}

0.10231{4}

0.07759{1}

0.08295{2}

Ranks

100

AVEs

1.10346

1.36260

1.36113

1.47760

1.41373

ABBs

0.39654{5}

0.14799{4}

0.14687{3}

0.10493{1}

0.11783{2}

MSEs

0.16058{5}

0.02903{4}

0.02836{3}

0.01690{1}

0.02007{2}

MREs

0.26436{5}

0.09866{4}

0.09791{3}

0.06996{1}

0.07856{2}

Ranks

One can note that the parameter estimates for both distributions are entirely good, that is, these estimates are quite reliable and very close to the true parameter values, showing small ABBs, MSEs and MREs for all values of the parameters and . The five estimators achieve the consistency property, where the MSEs, ABBs and MREs decrease as n increases, for all considered parametric values.

The performance ordering of these estimators is determined based on the partial and overall rank of the introduced estimators for both DPL and DL distributions which are listed in Table 7. Based on Table 7, we conclude that the performance ordering of these estimators, for the DPL distribution, from best to worst is WLSE, LSE, PCE, CVME, and MLE for all the studied cases. Furthermore, the performance ordering of these estimators, for the DL model, from best to worst is PCE, WLSE, LSE, CVME, and MLE for all the studied cases.

DPL

Parameter

n

MLE

CVME

LSE

PCE

WLSE

20

1

4

5

3

2

40

1

5

4

2

3

60

1

5

4

3

2

80

2

5

3

4

1

100

5

3

4

1

2

20

1

5

4

3

2

40

4.5

4.5

2

3

1

60

5

2

3

4

1

80

5

3

4

2

1

100

5

2

4

3

1

20

4

4

1.5

4

1.5

40

4.5

4.5

1

2.5

2.5

60

3.5

3.5

2

5

1

80

5

1

4

2.5

2.5

100

5

4

1

3

2

20

4.5

3

1

4.5

2

40

5

2

1

4

3

60

5

2

1

4

3

80

5

4

2.5

2.5

1

100

5

4

3

1.5

1.5

Ranks

77

70.5

55

61.5

36

Overall Rank

5

4

2

3

1

DL

Parameter

n

MLE

CVME

LSE

PCE

WLSE

20

1

4.5

4.5

2

3

40

1

5

4

2

3

60

1

4.5

4.5

2

3

80

1

5

3.5

2

3.5

100

1

4.5

4.5

2

3

20

2

4

5

1

3

40

5

4

3

1

2

60

5

2

3

4

1

80

5

3

4

2

1

100

5

2

4

3

1

20

5

3

1

4

2

40

5

2

1

3

4

60

5

4

1

2

3

80

5

3.5

3.5

2

1

100

5

3.5

3.5

1

2

20

5

3

1

4

2

40

5

3

4

2

1

60

5

3

4

1

2

80

5

3

4

1

2

100

5

4

3

1

2

Ranks

77

70.5

66

42

44.5

Overall Rank

5

4

3

1

2

In summary, we can conclude that the weighted least-squares method outperforms all other considered estimation methods with overall score of 36, hence this method is recommended to estimate the parameter of the DPL distribution, whereas the percentile method is recommended to estimate the DL parameter due to its superiority with overall rank of 42.

5 Modeling medicine data

In this section, we use three real-life data sets from medical science to show the superiority of the DPL and DL distributions by comparing them with some well-known discrete distributions such as discrete Pareto (DP) (Krishna and Pundir, 2009), discrete Burr (DB) (Krishna and Pundir, 2009) and discrete Burr-Hatke (DBH) (El-Morshedy et al., 2020) distributions.

The first data set contains 20 observations about the numbers of daily deaths in Saudi Arabia due to COVID-19 infections from 24 March to 12 April, 2020. The second data set contains 20 observations about the numbers of daily recover patients in Saudi Arabia from COVID-19 infections from 24 March to 12 April, 2020. The first and second data sets are reported on https://www.kaggle.com/sudalairajkumar/novel-corona-virus-2019-dataset/data#.

The third data set refers to remission times in weeks of 20 leukemia patients randomly assigned to a certain treatment (Lawless, 2011), and it was analyzed by Al-Babtain et al. (2020).

Based on our study in Section 4, we conclude that the weighted least squares (WLS) method is recommended to estimate the DPL parameter, and the percentile (PC) method is recommended to estimate the DL parameter. Hence, the WLS and PC methods will be applied in this section to estimate the parameters of both distributions from the three real data sets.

Table 8 reports the WLS estimates of the DPL distribution, lower limits (LL) and upper limits (UL) of the bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) and Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistics along with their associated p-values (KS-PV) for the three data sets. Further, the Pc estimates of the DL distribution, LL and UL of the bootstrap CIs, KS and its KS-PV for the three data sets were listed in Table 8.

Data

Distribution

WLS Estimates

LL

UL

KS

KS-PV

Data I

DPL

=0.07278

0.05382

0.10649

0.18382

0.50870

DB

1.41244

34.39454

0.25392

0.15164

0.79116

0.98987

—–

—–

DP

0.58620

0.81962

0.28408

0.07926

DBH

0.99989

0.99999

0.70001

0.00000

Data II

DPL

0.00372

0.00722

0.25158

0.13310

DB

0.75426

17.97669

0.38465

0.00358

0.82295

0.99039

—–

—–

DP

0.78640

0.91224

0.38665

0.00335

DBH

0.99989

0.99999

0.96668

0.00000

Data III

DPL

0.06989

0.14024

0.09792

0.99080

DB

1.34475

35.44724

0.29850

0.05665

0.79226

0.98992

—–

—–

DP

0.59074

0.82545

0.30059

0.05388

DBH

0.99989

0.99999

0.75001

0.00000

Data

Distribution

PC Estimates

LL

UL

KS

KS-PV

Data I

DL

0.05054

0.09936

0.18505

0.50001

DB

80.76587

99.69480

0.51712

0.00005

0.01396

0.99546

—–

—–

DP

0.32026

0.73038

0.53422

0.00002

DBH

0.00100

0.92293

0.98549

0.00000

Data II

DL

0.00366

0.00688

0.24941

0.13934

DB

4.40536

99.69480

0.76872

0.00000

0.00150

0.99564

—–

—–

DP

0.47984

0.81331

0.77764

0.00000

DBH

0.00010

0.92501

1.00000

0.00000

Data III

DL

0.06421

0.11654

0.10653

0.97706

DB

86.33405

96.47999

0.57943

0.00000

0.98601

0.99546

—–

—–

DP

0.31194

0.71604

0.60646

0.00000

DBH

0.00010

0.92164

0.96955

0.00000

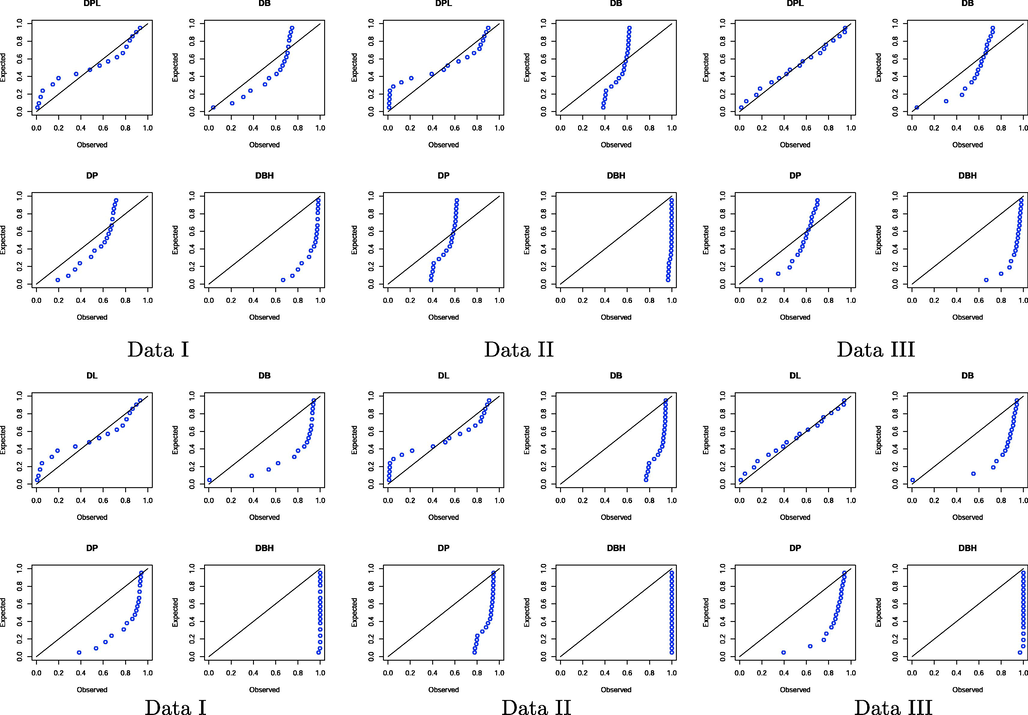

Fig. 2 displays the probability-probability (PP) plots of the fitted DPL and DL models and other distributions for the three data sets, respectively.

PP plots of the DPL (top panel) and DP (bottom panel) models and other models for three data sets.

Based on the KS and KS-PV, we conclude that the DPL and DL distributions provide adequate fit for the three data sets as compared with other discrete models.

6 Concluding remarks

In this paper, we derive two risk measures called value at risk and tail value at risk for the discrete Poisson-Lindley (DPL) and discrete Lindley (DL) distributions, and study their behavior using numerical simulations. Further, we discuss the estimation of the parameters for the two discrete distributions using five classical methods of estimation namely, the maximum likelihood, least squares, weighted least squares, percentiles, and Cramér-von Mises. We present detailed simulation results to compare these estimators in terms of mean square errors, average absolute biases, mean relative estimates, and total absolute relative errors of the parameters. The simulation study illustrates that all classical estimators perform very well and their performance ordering, depending on overall ranks, from best to worst is WLSE, LSE, PCE, CVME, and MLE for the DPL distribution. Further, the performance ordering for the DL parameter is PCE, WLSE, LSE, CVME, and MLE. The practical importance of the two distributions is discussed using three real-life data sets form medicine field. The DPL and DL distributions provide better fit for the three analyzed data than some other discrete distributions.

Funding

This project is supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2020/156) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Editor and two reviewers for their constructive comments that greatly improved the final version of the manuscript. This work was supported by King Saud University (KSU). The first author, therefore, gratefully acknowledges the KSU for technical and financial support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- A new three-parameter exponential distribution with variable shapes for the hazard rate: Estimation and applications. Mathematics. 2020;8(1):135.

- [Google Scholar]

- The heavy-tailed exponential distribution: Risk measures, estimation, and application to actuarial data. Mathematics. 2020;8(8):1276.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new discrete analog of the continuous lindley distribution, with reliability applications. Entropy. 2020;22(6):603.

- [Google Scholar]

- The odd exponentiated half-logistic exponential distribution: estimation methods and application to engineering data. Mathematics. 2020;8(10):1684.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new extended two-parameter distribution: Properties, estimation methods, and applications in medicine and geology. Mathematics. 2020;8(9):1578.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of coherent risk measures to capital requirements in insurance. North Am. Actuarial J.. 1999;3(2):11-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two parameter exponentiated gumbel distribution: Properties and estimation with flood data example. J. Stat. Manage. Syst.. 2017;20(2):197-233.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discrete Burr-Hatke distribution with properties, estimation methods and regression model. IEEE Access. 2020;8:74359-74370.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation methods for the discrete Poisson-Lindley distribution. J. Stat. Comput. Simul.. 2009;79(1):1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Computer methods for estimating Weibull parameters in reliability studies. IRE Trans. Reliab. Quality Control 1958:15-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- A graphical estimation of mixed Weibull parameters in life-testing of electron tubes. Technometrics. 1959;1(4):389-407.

- [Google Scholar]

- Loss models: from data to decisions,. Vol vol. 715. John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

- Discrete Burr and discrete Pareto distributions. Stat. Methodol.. 2009;6(2):177-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statistical models and methods for lifetime data. Vol vol. 362. John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

- Fitting the generalized Pareto distribution to data using maximum goodness-of-fit estimators. Comput. Stat. Data Anal.. 2006;51(2):904-917.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comments and queries comment on ’an estimation procedure for mixtures of distributions’ by Choi and Bulgren. J. Roy. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.). 1971;33(2):326-329.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new generalization of the exponentiated pareto distribution with an application. Am. J. Math. Manage. Sci.. 2018;37(3):217-242.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation methods of alpha power exponential distribution with applications to engineering and medical data. Pakistan J. Stat. Oper. Res. 2020:149-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Poisson exponential distribution: different methods of estimation. J. Appl. Stat.. 2018;45(1):128-144.

- [Google Scholar]

- On the generalized extended exponential-weibull distribution: Properties and different methods of estimation. Int. J. Computer Math.. 2020;97(5):1029-1057.

- [Google Scholar]

- Least-squares estimation of distribution functions in Johnson’s translation system. J. Stat. Comput. Simul.. 1988;29(4):271-297.

- [Google Scholar]