Entomotoxic proteins of Beauveria bassiana Bals. (Vuil.) and their virulence against two cotton insect pests

⁎Corresponding author. ksraj48@gmail.com (Kitherian Sahayaraj),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

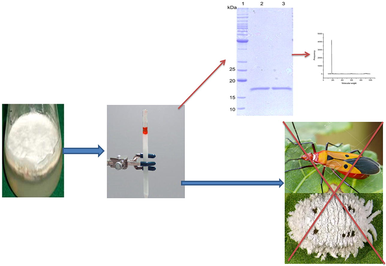

Entomopathogenic fungi are widely used as biocontrol agents against several agricultural pests. Among them, Beauveria bassiana is considered the important one against insect and other arthropod pests. The entomotoxic proteins of B. bassiana were extracted by Sephadex G-25 column, and fractionated using HPLC (BBI, BBII and BBIII) and tested against two hemipteran insect pests i.e., Dysdercus cingulatus Fab. and Phenacoccus solenopsis Tinsely (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). Results indicated that protein content was higher in fraction BBII than BBI and BBIII. The vibration frequency in FT-IR obtained with a range of 1650 to 1580 cm−1. Bioassays of fractions (I, II and III) reveal that BBII was highly virulent against third nymphal instar of D. cingulatus (LC50 = 800.2 ppm) and adults of P. solenopsis adult (LC50 = 713.3 ppm). Considering the high virulence of BBII subjected to SDS-PAGE, HPLC and MALDI-TOF analyses. Analyses reveals the presence of 174 kDa and designated as BBF2. These results concluded that the entomotoxic protein of B. bassiana can be utilized for management of these investigated hemipreran pests. Further investigations are necessary for the field application of this entomotoxin against these pests or other insect pests. These results also could be helpful for establishing novel biotechnological uses for this fungus.

Keywords

Beauveria bassiana

Entomotoxin

Characterization

Insecticidal activity

1 Introduction

Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) are widely available as biological control agents against various agricultural pests (Safavi, 2013). Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) is an important natural pathogen of insects and other arthropods, able to cause epizootics among populations of invertebrates including insects (Sayed et al., 2019). It has been used as a microbial insecticide against various pests such as lepidopteran (Safavi, 2013) hemipteran (Rohlfs and Churchill, 2011), coleopteran (Meyers et al., 2013) and orthopteran (Pelizza et al., 2013) pestiferous insects and parasites (Wang and St. Leger, 2007). B. bassiana is capable of penetrating through the insect cuticle, secreting cuticle-degrading enzymes such as lipases, chitinases and proteinases (Lakshmi et al., 2010) being effective against insect pests.

The EPF have slow mortality rate as compared to synthetic insecticides (St. Leger and Wang, 2009). Therefore, the use of EPF could be increased, if their killing efficiency is improved. The higher killing efficiency could be achieved by different methods such as enhancing the production of fungal toxins. Many of EPF secrete anti-feedants, insecticidal, or toxic compounds in liquid cultures (Abd-ElAzeem et al., 2019). Many investigations have been done on B. bassiana for the identification of cuticle degrading enzymes and determinants (Griesch and Vilcinskas, 1998).

Most of EPF release various cyclic peptides and small secondary metabolites as enniatins, beauvericin, oxalic acid, oosporein, bassianolide and elicitor proteins. These compounds are demonstrated to have insecticidal effects (Nazir et al., 2020). Identification and isolation of the genes encoding these toxic proteins and purification of them will introduce important knowledge on their mode of action and nature (Ortiz-Urquiza et al., 2010). Other Bb70p, a toxin protein of B. bassiana with 35.5 kDa, had a toxic impact against Galleria mellonella larvae and had high activity up to 40 °C, and also stable in the 4–10 pH range (Khan et al., 2016).

Control of Dysdercus cingulatus Fab. (Hemiptera: Pyrrhocoridae) and Phenacoccus solenopsis Tinsely (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) are preliminarily accomplished through the use of conventional insecticides. The negative impact of chemical control has encouraged the development of alternative pest management strategy such as fungal entomotoxins (Molnar et al., 2010). B. bassiana produces various toxic compounds in vivo and in vitro having low molecular weight secondary metabolites (Zimmermann, 2007). Among them, Beauvericin showed insecticidal activity against many insect pests (Vey et al., 2001). There are no reports available about the B. bassiana entomotoxic protein against D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis. This study was aimed to extract and purify the entomotoxic protein of B. bassiana, followed by its molecular characterization and estimating its potential bioactivity against two hemipteran insect pests, i.e., D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Fungal strain

The B. bassiana (MTCC 2028) isolate which maintained in the Crop Protection Research Center, St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Palayamkottai was used for the current study. For inoculation, 103B. bassiana conidia were inoculated into 100 mL of potato dextrose broth (Himedia, Mumbai) in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The culture was incubated on a rotator shaker (180 rpm) at 27 °C for 7 days and the spore concentrations recorded using a haemocytometer. Viability of conidia was checked before preparation of suspension by germinating test in liquid Czapek-Dox broth with 1% (w/v) yeast extract medium (CDBYEM) to harvest conidia. For large scale growth of the fungus, 2 mL of primary culture was inoculated into 250 mL of the same medium and cultured at 25 °C for 20 days.

2.2 Isolation of culture filtrate

After 20 days of growth in CDBYE medium, the protein filteration and precipitation were done according to Quesada-Moraga and Vey (2004). The crude protein was subjected to a gel filtration using a Sephadex G-25 (Sigma) column (1×10 cm) in 50 mM tris/HCl buffer at pH 8. The column flow rate was adjusted at the rate of 1 mL/hr. The aliquots were collected and subjected to UV, FT-IR, HPLC and MALDI-TOF.

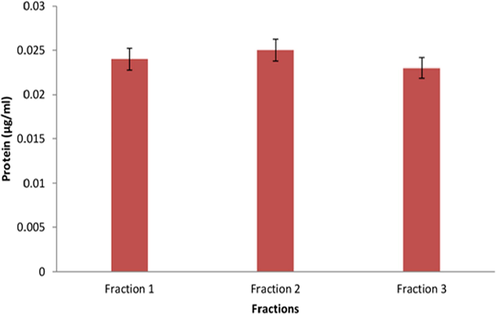

2.3 Determination of total protein concentration

Total protein concentration of B. bassiana entomotoxin was investigated with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (S.D. Fine-Chem Limited, Mumbai) according to Lowry et al. (1951).

2.4 Characterization of entomotoxin

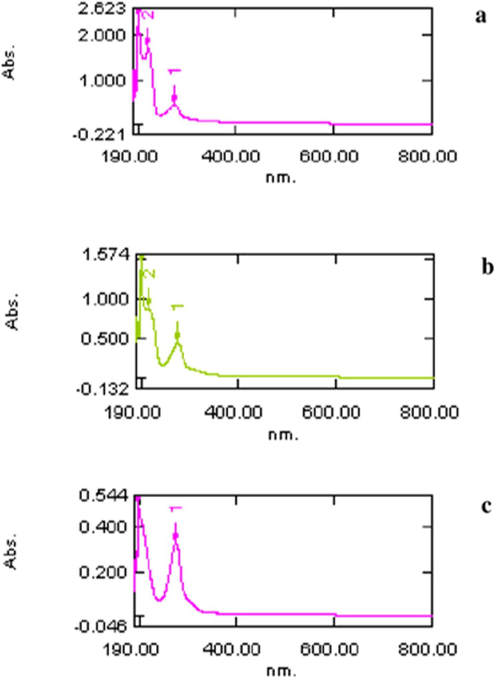

2.4.1 UV–spectroscopy analysis

The fungal protein fractions were assessed by UV spectrometer (Schumadzu, Japan) to investigate protein content. The absorbance peak readings of all fractions were recorded and categorized into 3 fractions i.e., fraction I (FI), fraction II (FII) and fraction III (FIII).

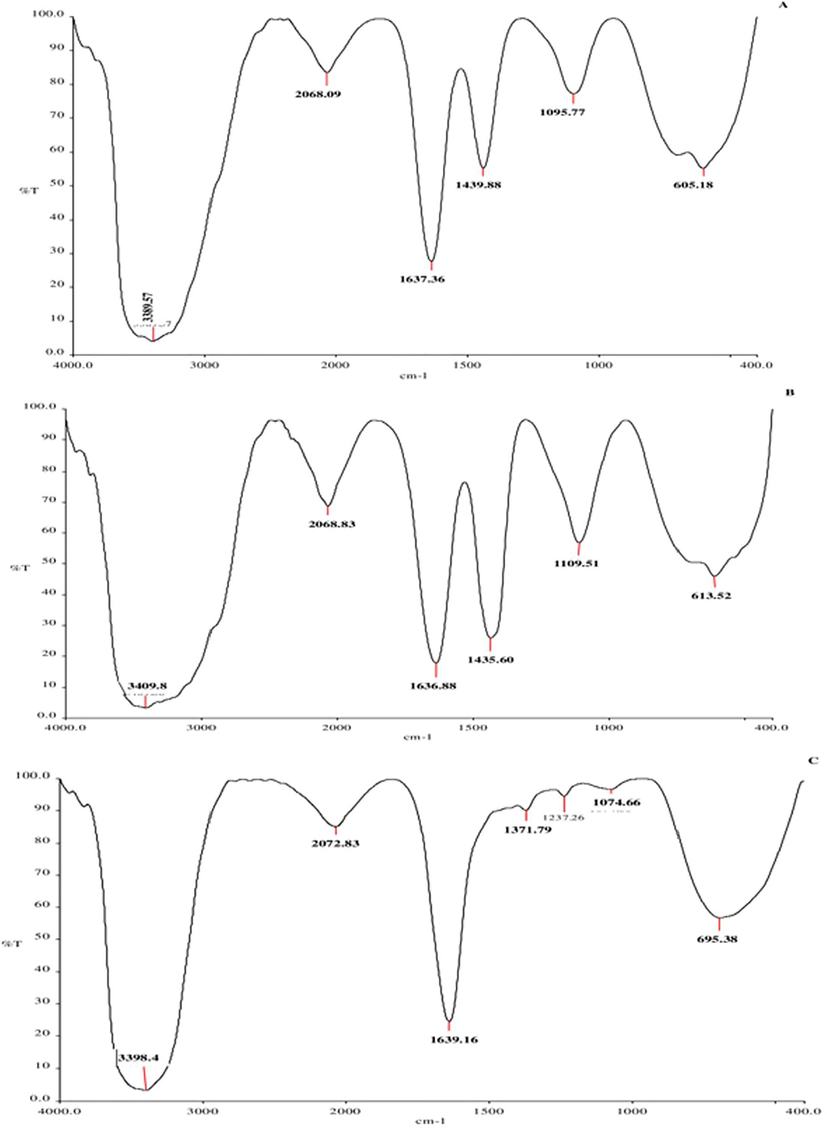

2.4.2 Analysis of fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

FT-IR spectra of FI, FII and FIII was determined using a FTIR spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Spectrum RX I, Japan) in a range of 4000 to 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The FT-IR was done separately for each sample to identify the possible resonance vibration of chemical bonds.

2.4.3 Gel electrophoresis of B. Bassiana entomotoxin

Tricine-SDS-PAGE was used to investigate the numbers and relative molecular weights of polypeptides/proteins obtained from B. bassiana entomotoxin according to Schagger and Jagow (1987).

2.4.4 High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

The B. bassiana entomotoxin (FII) was analyzed on a HPLC (Schimadzu LC/10AD, Japan). The analytical chromatogram indicated one major compound UV maximum at 3000 nm. The procedure yielded 5 mL of a pure white column solution.

2.4.5 Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-TOF (MALDI–TOF)

Liquid fraction II obtained from the preparative HPLC was dried. Then, it was subjected to MALDI-TOFMS analyses (Voyager-DETM PRO BiospectrometryTM spectrometer (Applied BioSystems, Framingham, MA, USA). Each experiment was facilitated with the Voyager v.5 with Data ExplorerTM software.

2.5 Collection and rearing of tested insects

Nymphs and adults of D. cingulatus were collected from a cotton field, Tirunelveli District, Tamil Nadu, India. Collected individuals were reared under laboratory condition (28 ± 2 °C temperature, 70–75 RH, 11L: 13D photoperiod) in plastic container (13 cm height ×7 cm diameter) primarily provided with water soaked cotton seeds, later with artificial diet (Sahayaraj et al., 2011). The newly hatched third instars were used for bioassay experiments. Individuals of P. solenopsis were collected from the field and cultured on clean pumpkin (Venkatesha and Dinesh, 2011). The laboratory emerged insects were used for the study.

2.6 Bioassay

Adults of P. solenopsis (0–1 day old) (17.4 ± 0.3 mg) and third instar of D. cingulatus (0 day old) (43.7 ± 0.3 mg) were maintained as previously described by Sahayaraj et al., 2011; Venkatesha and Dinesh, 2011), respectively. Then, different concentrations of B. bassiana entomotoxic fractions (FI, FII and FIII) were prepared such as 100, 200, 400, 800 and 1600 ppm by adding required amount of distilled water. For oral toxicity bioassay, different concentrations of FI, FII and FIII were mixed with 5 mL of artificial diet (Sahayaraj et al., 2011) and 50 µL of diet was poured into 10 mg of cotton ball and provided to D. cingulatus daily. Leaf dip method was followed for P. solenopsis adult (Cuthbertson et al., 2009). For leaf-dip bioassay, 10 mL of each different fraction concentration was taken in a 100 mL beaker into which were added 50 µL (0.05%) Tween 80 and mixed well. Healthy cotton leaves were dipped separately in the tested concentrations for 10 min then air dried for 5 min. The air dried leaves of various concentrations were kept in a Petri dish (9 cm diameter ×1 cm height) and adults of P. solenopsis were introduced and allowed to feed the leaves. The mortality of insects was recorded every 24 hrs up to 96 hrs continuously. All treatments were replicated 3 times with ten individuals/replicate.

2.7 Enzyme quantification

Each enzyme sample was prepared according to Applebaum et al. (1961). After 96 hrs of exposure period, the live insects were supplied with normal feed (artificial diet for D. cingulatus and normal cotton leaves (SVPR IV for P. solenopsis) and maintained under laboratory condition mentioned above. After the adulteration of the insects, three live as well as healthy D. cingulatus and five P. solenopsis adults from each concentration (100, 200, 400, 800 and 1600 ppm) of fungal fraction II and control categories were starved for 12 hrs before dissection for the accumulation of digestive enzymes.

2.7.1 Digestive enzyme (Amylase)

Amylase activity in animal gut was determined according to Ishaaya and Swirski (1970). The enzyme activity was expressed in terms of the weight of the reducing sugar, glucose (g) produced by the enzyme action per unit weight of gut, per unit time, using glucose as the standard. Proteolytic activity was assayed spectrometrically (Morihara and Tsuzuki, 1977). The protease activity was expressed as µmoles of tyrosine released per minute per mg of protein.

2.7.2 Detoxification enzymes

Esterase: The degradation rate of α – and β – Naphthyl acetate was determined according to Asperen (1962). The absorbence was read at 600 nm for α naphthol and at 550 nm for β – naphthol.

Glutathion S – transferase: The activity was measured with 1 –Chloro − 2, 4 – dinitrobenzene (CDNB) as substrate according to Yu (1982).

Lactate dehydrogenase: The enzyme activity is expressed as multi International Unit (mIU) per milligram protein/minute (King, 1965).

2.8 Gel electrophoresis of insects total body protein profile

The protein profiles of D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis treated with fungal fraction II, were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with 12% gels and the buffer system (Laemmli, 1970). Gels were scanned with gel documentation system (Biotech – India) for analysis.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The LC50 (Lethal concentration of protein to kill 50% of treated individuals) values and their fiducial limits were estimated by Probit analysis. The data obtained from the enzyme level of insects were analyzed by MANOVA and Tukey’s test (P < 0.05) using SPSS software version 20.0.

3 Results

3.1 Purified entomotoxin

It was observed that the total protein surface plasmon resonance band occurs initially at ca. 210 nm. The proteins surface plasmon band obtaind between 210 and 280 nm in the aqueous medium (Fig. 1). Based on the UV absorption the eluents were categorized into 3 fractions: fraction I (FI), fraction II (FII) and fraction III (FIII). The total protein content was significantly higher in FII followed by FI and FIII (Fig. 2).

- UV – visible spectroscopy analysis of B. bassiana protein fractions: fraction I (a), fraction II (b) and fraction III (c) eluted from Sephadex G-25.

- Protein quantity (µg/ml) of B. bassiana protein fractions: fraction I, fraction II and fraction III eluted by Sephadex G-25 column.

3.2 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis

FTIR analyses reveal that the FI, II and III shows characteristic vibration between 1637 and1639 cm−1(N—H for amines) and between 1435 and1440 cm−1 (C—H for methyl group) (Fig. 3).

- FT-IR analysis of B. bassiana protein fractions: fraction I (a), fraction II (b) and fraction III (c).

3.3 SDS-PAGE – entomotoxin

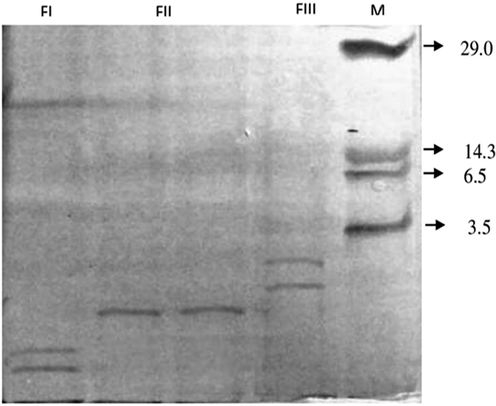

The SDS-PAGE analyses indicated that the fractions contain various polypeptides with low molecular weights where FI (M.W. 16,215 and 19104) and FIII (M.W. 3026 and 7004) contain two polypeptide bands and FII contains a single band (M.W. 10656) (Fig. 4).

- Protein banding pattern of B. bassiana entomotoxins eluted using Sephadex G-25 column. M – low molecular weight marker (kDa); BBFI, BBFII and BBF III.

3.4 Analysis of high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

The samples of FII were preliminarily subjected to analytical HPLC. Two peaks were obtained with retention time of 4.262 min−1with an area of 95.69% (FIIa) and 5.915 min−1 with an area of 4.1% (FIIb). Then, the fractioned HPLC of FII was subjected to preparative HPLC for estimating the major polypeptide per peak. It has a retention time of 10.18 min−1 (area 100%) with methanol as the solvent.

3.5 Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-Time of flight (MALDI–TOF)

The purified single peptide obtained by the preparative HPLC (FIIa) was analyzed by MALDI-TOF. The obtained peak was at the molecular weight of 174 kDa and it was designated as BBF2.

3.6 Bioassay

Dose dependent mortality was recorded for FI, FII and FIII against the insects. FII was highly toxic to both insects rather than FI and FIII (Tables 1 and 2). When compared to the FIII, the LC50values of FII were reduced by 27% and 38% at 96 hrs for D. cingulatus and

| Concentration (ppm) | Fraction I | Fraction II | Fraction III |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 10.3 ± 0.33a | 10.3 ± 0.33a | 3.3 ± 0.33b |

| 200 | 21.9 ± 0.45b | 33.3 ± 0.14a | 10.3 ± 0.33c |

| 400 | 33.3 ± 0.33b | 45.6 ± 0.14a | 18.7 ± 0.24c |

| 800 | 41.2 ± 0.12b | 51.3 ± 0.21a | 20.5 ± 0.02c |

| 1600 | 45.6 ± 0.21b | 55.57 ± 0.32a | 23.3 ± 0.05c |

| Lethal concentrations | |||

| LC30 | 637.3 | 240.1 | 1816.1 |

| LC50 | 1554.6 | 800.2 | 2991.3 |

| LC90 | 3796.5 | 3204.6 | 5865.5 |

| Slope | 5.3 | 5.7 | 3.6 |

| Chi-square | 13.38 | 26.3 | 10.3 |

| Regression equation | Y = −486.1 + 36.3X | Y = −396.7 + 25.9X | Y = −297.3 + 60.3X |

Means within each row bearing different letters are significantly different according to Tukey’s test (α = 5%).

| Concentration (ppm) | Fraction I | Fraction II | Fraction III |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 21.43 ± 0.03a | 20.69 ± 0.02a | 6.90 ± 0.02b |

| 200 | 25.00 ± 0.03a | 27.59 ± 0.03a | 10.34 ± 0.12b |

| 400 | 39.29 ± 0.05a | 44.83 ± 0.14a | 17.24 ± 0.03b |

| 800 | 50.00 ± 0.04a | 51.72 ± 0.12a | 20.69 ± 0.03b |

| 1600 | 58.63 ± 0.04a | 61.67 ± 0.14a | 28.34 ± 0.03b |

| Lethal concentrations | |||

| LC30 | 227.0 | 119.9 | 1823.5 |

| LC50 | 871.14 | 713.3 | 9249.7 |

| LC90 | 23302.7 | 15970.4 | 489,293 |

| Slope | 6.0 | 6.7 | 4.47 |

| Chi-square | 6.58 | 1.11 | 0.29 |

| Regression equation | Y = −770.5 + 35.7X | Y = −729.5 + 32.7 | Y = −525.9 + 68.6 |

Means within each row bearing different letters are significantly different according to Tukey’s test (α = 5%).

P. solenopsis respectively. Significant differences in LC50 (P < 0.05) were identified among the 3 fractions for D. cingulatus but significant difference was obtained between FIII and both of FI and FII for P. solenopsis.

3.7 Biochemical analyses

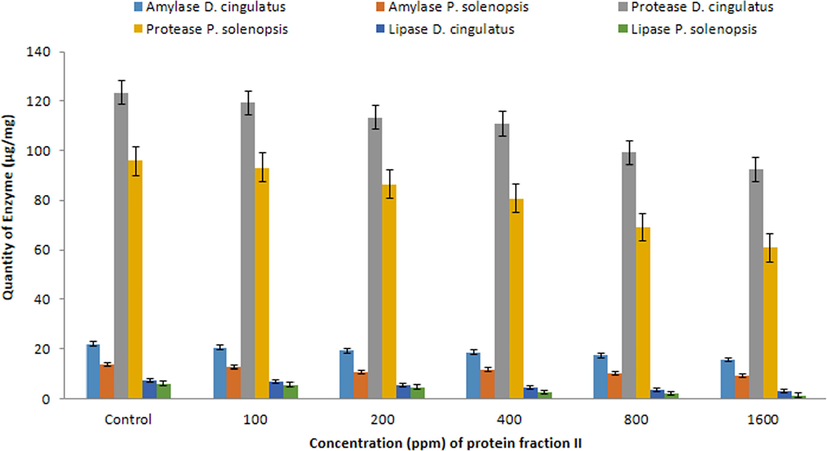

3.7.1 Digestive enzymes

The quantity of digestive enzymes such as amylase (F5,12 = 54.50, p = 0.05), protease (F5,12 = 60.20, P = 0.05) and lipase (F5,12 = 9.827, P = 0.01) in D. cingulatus decreased while the concentration of FII was increased. Similar kind of observation was also recorded for P. solenopsis (F5,12 = 43.60, P = 0.05; F5,12 = 182.578, P = 0.05; F5,12 = 9.926, P = 0.01 for amylase, protease and lipase respectively). Highly significant reduction was observed in 1600 ppm for both D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis (Fig. 5).

- Quantitative analysis of Amylase, Protease and Lipase (µg/mg) in D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis treated with B. bassiana entomotoxic protein (FII).

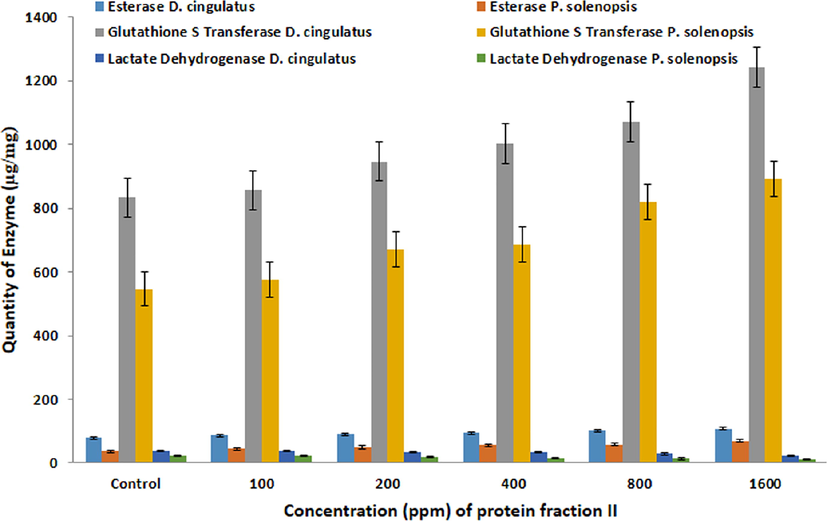

3.7.2 Detoxification enzymes

The quantity/activity of detoxification enzymes such as esterase (F = 149.367, df = 5, 12, p = 0.05), glutathione s-tranferase (F5,12 = 204.73, P = 0.05) and lactate dehydrogenase (F5,12 = 17.185, P = 0.05) were increased when the concentration of B. bassiana fraction II (FII) increased in D. cingulatus. Also in P. solenopsis,the quantity/activity of Esterase (F5,12 = 36.706, P = 0.05), glutathione s-tranferase (F5,12 = 132.73, P = 0.05) and lactate dehydrogenase (F5,12 = 19.566, P = 0.05) were also increased at 1600 ppm (Fig. 6).

- Quantitative analysis of Esterase, Glutathione S Transferase, Lactate Dehydrogenase (µg/mg) in D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis treated with B. bassiana entomotoxic protein (FII).

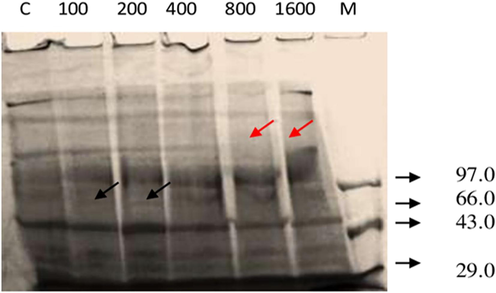

3.7.3 SDS-PAGE – Insect total body protein profile.

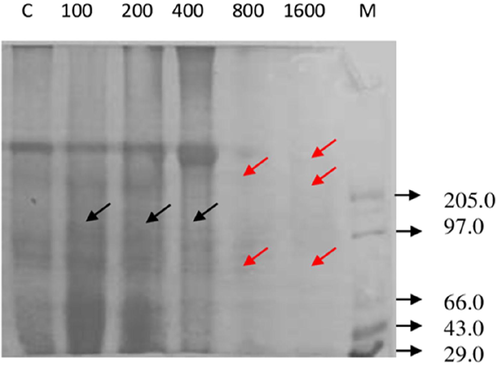

The total body protein profile of D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis treated with different concentration of entomotoxin is shown in plate 4 and 5 respectively. The intensity of protein bands diminished when the concentration of the entomotoxin increased both in D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis. Totally nine peptide bands became visible for D. cingulatus in control categoryand it was sustained in lower concentrations (100 and 200 ppm) of FII. The concentration of FII increased the peptide band that disappeared and was the least in higher concentrations, such as 800 ppm and 1600 ppm (Fig. 7). The same kind of result was observed for P. solenopsis. Eight bands appeared in control category and also in lower concentrations (100 ppm and 200 ppm) and 50% of bands were disappeared in higher concentration (1600 ppm) (Fig. 8).

- Protein banding pattern of D. cingulatus treated with B. bassiana entomotoxic Fracton II (FII) of Sephadex G-25 column at different concentrations (ppm). Dense appearance of protein pattern was showed separately. M – low molecular weight marker (kDa); C – control; Black arrows indicates induction of new polypeptides; Red arrows indicates disappearance of the polypeptides.

- Protein banding pattern of P. solenopsis treated with B. bassiana entomotoxic Fracton II (FII) of Sephadex G-25 column at different concentrations (ppm). Dense appearance of protein pattern was showed separately. M – low molecular weight marker (kDa); C – control; Black arrows indicate induction of new polypeptides; Red arrows indicate disappearance of the polypeptides.

4 Discussion

Genus Beauveria contains several species which show enhanced pathogenicity against their host insects. The enhanced pathogenicity in these species is linked to toxins production (Lakshmi et al., 2010). All fungi probably produce mycotoxins, with low molecular weight and are generally considered nonvolatile (Dhar and Kaur, 2010). The intracellular proteins were isolated from B. bassiana with specific medium under stress conditions and their insecticidal activity was tested against lepidopteran larvae (Quesada-Moraga and Vey, 2004). In this study, the intracellular proteins were precipitated using 90% saturated Ammonium sulphate solution and the efficacy evaluated against D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis.

In the current study, the fractions indicated the absorption of proteins. Also, each sample was subjected to FT-IR spectra. Moreover, when the purification/specificity of the polypeptide increased, the quantity of protein content decreased. The same finding was observed by Urtz and Rice (2000). The three entomotoxin fractions of B. bassiana indicated low quantity level of proteins; on the other hand F II has the higher protein content. The spectrum results indicated that the proteins are found as secondary amines. Previous findings indicated that the filamentous fungi as B. bassiana contain multiple types of enzymes (Rohlfs and Churchill, 2011; Molnar et al., 2010).

Analytical HPLC spectrum of B. bassiana entomotoxin indicated 2 polypeptides found in F II at a retention time of 4.2 min (95.6%) and 5.9 min (4.4%). In previous investigation, tyrosine betaine was found as an entomotoxic secondary metabolite from Metarhizium sp. having a retention time of 4.1 min (Carollo et al., 2010). The current investigation stated the toxicity of B. bassiana FII. The major peak of FII was collected by preparative HPLC at a retention time of 10.1 min and identified by MALDI-TOF as 174 kDa.

In general, applications of purified toxins are sufficient to achieve death in susceptible insects (Cuthbertson et al., 2009). In the current study, the entomotoxin FII of B. bassiana achieved high mortality against P. solenopsis (61.7%) and D. cingulatus (55.5%). Many reports stated the insecticidal activity of B. bassiana metabolites against different insect pests such as Beauvericin (M.W. 28 kDa) (Safavi, 2013), bassianin (M.W. 18 kDa), bassianolide (M.W. 390 kDa), beauverolides (M.W. 72 kDa) (Vey et al., 2001), tenellin (M.W. 60 kDa) (Zimmermann, 2007), and bassiacridin (M.W. 89 kDa) (Quesada-Moraga and Vey, 2004).

The preoteolytic enzymes from B. bassiana were investigated as the mortality factor (Dhar and Kaur, 2010). Dose dependent mortality was estimated in the current investigation. Higher mortality in D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis was observed after 96 h of the exposure at higher concentration (1600 ppm) of FII. Amylase, protease (Uzma and Kaur, 2010) and lipase (López-Rodríguez et al., 2012) play important roles in the digestion of plant starch, proteins and lipids respectively in insects. Our results reveal the digestive enzyme activities decreased with increasing concentration of B. bassiana FII fraction, leading to improper digestion of proteins to amino acid conversion. Further, the level of amylase decreased directly proportional to the B. bassiana entomotoxin FII concentration. Mycotoxins interrupted the secretion of digestive enzymes and led to the disruption of gut physiology (Sahayaraj et al., 2010). In this study, the protease level decreased due to effect of B. bassiana entomotoxin FR II. Another suggestion proposed by researchers is decreased protease level can be due to the impact of mycotoxins on neurosecretory cells of the insects (López-Rodríguez et al., 2012).

Esterase and glutathione S-transferase (GST) play a significant role in insecticide metabolism (Alizadeh et al., 2010). In general, the increased levels of esterase and GST due to more catalytically efficient enzyme able to hydrolyse the insecticides in insects (Montella et al., 2012). In this study, significantly maximum LDH activity in control category was observed in the midgut whereas in the treatment it was reduced. Therefore, this enzyme may be a sensitive criterion for entomotoxin (Diamantino et al., 2001). The analytical SDS-PAGE of D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis indicated that B. bassiana entomotoxic fraction II has high impact on the total body protein content of the insects. When compared with the control category, in higher concentration treatments the protein bands disappeared and new protein bands appeared as previously reported in Galleria mellonella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) (Vey et al., 2001). They observed that the toxin beauveriacin altered the total body protein profile of the animal.

5 Conclusions

The entomopathogen of B. bassiana can be utilized for cotton pest management. The application of toxin under field condition requires further processing. In the present study we identified the B. bassiana entomotoxic protein (FII) supported by UV-visible spectroscopy, FT-IR spectroscopy, HPLC and MALDI-TOF analyses and its insecticidal activity against two major cotton pests. The molecular weight of the FII was identified as 174 kDa. FII showed high impacts on D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis under laboratory condition. The quantities of digestive enzymes were decreased and detoxification increased in cotton pests which indicate that FII also affects the physiology of insects. Hence, it could be concluded that the entomotoxic protein and its SNP’s can be utilized for the management of D. cingulatus and P. solenopsis, also it can be used as the component of BIPM. Therefore, further investigations are needed to study the toxicity of these entomotoxin proteins to other insect pests such as lepidopterous insect pests and aphids.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP -2020/92), Taif university, Taif, Saudi Arabia. Also, the authorities of St. Xavier’s College.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Biological activities of spores and metabolites of some fungal isolates on certain aspects of the spiny bollworms Earias insulana (Boisd.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Egyptian Journal of Biological. Pest Control. 2019;29:90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of insecticide resistance and biochemical mechanism in two populations of Eurygaster integriceps Puton (Heteroptera: Scutelleridae) Munis Entomology and Zoology. 2010;5(2):734-744.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on the mid gut amylase activity of Tenebrio molitor L. larvae. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1961;7:100-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- study of housefly esterases by mean of a sensitive colorimetric method. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1962;8:401-416.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fungal tyrosine betaine, a novel secondary metabolite from conidia of entomopathogenic Metarhizium spp. Fungal Biology. 2010;114(5/6):473-478.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leaf dipping as an environmental screening measure to test chemical efficacy against Bemisia tabaci on poinsettia plants. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 2009;6(3):347-352.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of cuticle – degrading proteases by Beauveria bassiana and their induction in different media. African Journal of Biochemistry Research. 2010;1(3):98-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lactate dehydrogenase activity as an effect criterion in toxicity test with Daphnia magna Straus. Chemosphere. 2001;45:553-560.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proteases released by entomopathogenic fungi impair phagocytic activity, attachment and spreading of plasmatocytes isolated from the haemolymph of the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 1998;8:517-531.

- [Google Scholar]

- Invertase and amylase activity in the armoured scales Chrysomphalus aonidum and Aonidiella aurantii. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1970;16:1599-1606.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification and characterization of an insect toxin protein, Bb70p, from the entomopathogenic fungus, Beauveria bassiana, using Galleria mellonella as a model system. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 2016;133:87-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- King, J. 1965. The dehydrogenase or oxidoreductases. Lactate dehydrogenase.In: Practical clinical enzymology. Van Nostrand, D. company London 83-93.

- Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680-685.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and purification of cuticle degrading extracellular proteases from entomopathogenic fungal species Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae. African Journal of Biochemistry Research. 2010;4(3):65-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Digestive enzyme activity and trophic behavior in two predator aquatic insects (Plecoptera, Perlidae). A comparative study. Com Biochem Physiol Part A: Molecular International. Physiology. 2012;162(1):31-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protein measurement with folin phenol reagent. Journal of Biochemistry. 1951;193:265-275.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory and field bioassays on the effects of Beauveria bassiana Vuillemin (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) on red oak borer, Enaphalodes rufulus (Haldeman) (Cleoptera: Cerambycidae) Biological Control. 2013;65(2):258-264.

- [Google Scholar]

- Secondary metabolites from entomopathogenic hypocrealean fungi. Natural Product Reports. 2010;27(9):1241-1275.

- [Google Scholar]

- The classification of esterases: an important gene family involved in insecticide resistance – A Review. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107(4):437-449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of protease and elastase by Pseudomonas aeuroginose strains isolated from patients. Infiction and Immunity. 1977;15:679-685.

- [Google Scholar]

- Putative Role of a Yet Uncharacterized Protein Elicitor PeBb1 Derived from Beauveria bassiana ARSEF 2860 Strain against Myzus persicae (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis. Pathogens. 2020;9(2):111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insect-toxic secreted proteins and virulence of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 2010;105(3):270-278.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survival and fecundity of Dichroplus maculipennis and Ronderosia bergi (Orthoptera: Acrididae: Melanoplinae) following infection by Beauveria bassiana (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) under laboratory conditions. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 2013;23(6):701-710.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bassiacridin: A protein toxic for locusts secreted by the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Mycological Research. 2004;108:441-452.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fungal secondary metabolites as modulators of interactions with insects and other arthropods. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2011;48:23-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro and in vivo induction and characterization of beauvericin isolated from Beauveria bassiana and its bioassay on Galleria mellonella larvae. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology. 2013;15:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Artificial rearing of the red cotton bug, Dysdercus cingulatus using cotton seed based artificial diet (Hemiptera: Pyrrhocoridae) Entmologia Generalis. 2011;33(4):283-288.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gross morphology of feeding canal, salivary apparatus and digestive enzymes of salivary gland of 100 Catamirus brevipennis (Servile) (Hemiptera: Reduvidae) Journal of Entomological Research Society. 2010;12(2):37-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of indigenous entomopathogenic fungus, Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin isolates against rose aphid, Macrosiphum rosae L. (Homoptera: Aphididae) in rose production. Egyptian Journal of Biological. Pest Control.. 2019;29(19)

- [Google Scholar]

- Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1–100 kDa. Analytical Biochemistry. 1987;166:368-379.

- [Google Scholar]

- Entomopathogenic fungi and the genomic era. In: Stock S.P., Vandenberg J., Glazer I., Boemare N., eds. Insect Pathogens: Molecular Approaches and Techniques. Wallingford, UK: CABI; 2009. p. :366-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Purification and characterization of a novel extracellular protease from Beauveria bassiana. Mycological Reseach. 2000;104:180-186.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on extracellular enzyme production in Beauveria bassiana isolates. International Journal of Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2010;6(5):701-713.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mass rearing of Spalgis epius (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae), a potential predator of mealy bugs (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) Biocontrol Science and Technology. 2011;21(8):929-940.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fungi as biocontrol agents: progress, problems and potential. Wallingford: CABI; 2001. p. :311-346.

- [CrossRef]

- Scorpion neurotoxin increases the potency of a fungal insecticide. Nat Bul Biotech. 2007;25:1455-1456.

- [Google Scholar]

- Host plant induction of glutathione S – transferase in the fall armyworm. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 1982;18:101-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review on safety of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Beauveria brongniartii. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 2007;17(5/6):553-596.

- [Google Scholar]