Translate this page into:

Entomopathogenic fungi and their biological control of Tetranychus urticae: Two-spotted spider mites

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Biology, College of Science, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia. nmalabdallah@iau.edu.sa (Nadiyah M. Alabdallah)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

The two-spotted spider mite (TSSM) Tetranychus urticae, is regarded as one of the most dangerous pests responsible for great losses in most of agricultural crops. It is a persistent pest in Saudi Arabia, especially in greenhouses where T. urticae is primarily controlled by chemical pesticides. The main problem for the two-spotted spider mites is its high resistance to pesticides and high fertility rate. In the long term, chemical pesticides cause health problems and economic losses, so it was necessary to search for a safe alternative method for human health and the environment. One of these alternative methods was the selection of plant varieties resistant to the TSSM, in addition to biological control that includes mites or predatory insects and entomopathogenic fungi. The growth, reproduction, and life-table parameters of T. urticae were examined in a laboratory setting with a 16L:8D photoperiod at 28 ± 1 °C and 65 ± 5% RH, in the presence of three major members of Family: Solanaceae tomato, eggplant, and pepper. Pepper was shown to be less conducive to T. urticae growth and reproduction compared to eggplant and tomato. Tetranychus urticae proceeded through all five stages of its life cycle (egg, larva, protonymph, deutonymph, and adult) on tested solanaceous plants, and these plants significantly influenced its growth, reproduction, and Life-table parameters. Additionally, entomopathogenic fungi have been used against insects that have proven highly effective in controlling and reducing the density of two-spotted spider mites. Eight fungi were isolated from 80 insect and mite samples collected from several Saudi Arabia regions. Analysis of the 18S rRNA sequences revealed that the fungal strains identified as Beauveria bassiana, Fusarium sp. F. equiseti, F. oxysporium, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis1, S. brevicaulis2, Aspergillus sclerotiorum, and Penicillium citrinum. The ability of isolated fungi to secrete enzymes degrading the two-spotted spider mite cuticle, namely lipase, protease, and chitinase, were studied.

Keywords

Entomopathogenic fungi

Beauveria bassiana

Biological control

Tetranychus urticae

Phytophagous mite

- ANOVA

-

Analysis of variance

- BLAST

-

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- Co

-

Control

- CZA

-

Czapek Dox Agar

- DNA

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EPF

-

Entomopathogenic fungi

- DT

-

Generation Doubling Time

- g/L

-

Gram per litter

- GRR

-

gross reproductive rate

- h

-

Hours

- L

-

Light

- T

-

Mean Generation Time

- ml/L

-

Milli per litter

- NCBI

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- R0

-

Net reproductive rate

- No

-

Number

- PCR

-

Polymerase chain Reaction

- ±SE

-

Positive or negative standard error

- PDA

-

Potato Dextrose Agar

- RPW

-

Red Palm Weevil

- RH

-

Relatively Humidity

- rpm

-

Revolution per minute

- SDA

-

Sabouraud Dextrose Agar

- TBA

-

Tributyrin Agar

- TSSM

-

Two Spotted Spider Mite

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

The Two-Spotted Spider Mite (TSSM), or Tetranychus urticae (Koch) (Acari: Prostigmata: Tetranychidae) is a pest in both open and closed crop environments worldwide (Daniels et al., 2023). TSSM feeds on more than 3,877 different types of host plants and is known to cause economic damage to at least 150 plants (Elhakim et al., 2020). Globally, T. urticae is responsible for a loss of 10 % to 50 % of the production of tomatoes. On the other hand, its effect is not limited to the productivity of fruits, but it extends to the quality and size of fruits and consequently to the marketing value of the fruit (Meck et al., 2012). In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, only 18 species of spider mites were identified from the ten genera of Tetranychidae (Acari: Prostigmata) from different localities (e.g., Al-Riyadh, Al-Baha, Al-Qassim, Al-Medina, Makkah, Tabuk, Wadi Al-Dawasir, and Al-Ahsa (Mushtaq et al., 2023). Chemical control of this spider mite was the main method and, until now, largely dependent on acaricides and insecticides (Wu et al., 2019). Increased use of chemical insecticides, which lowered the number of natural predators and reduced predation pressure, may be to blame for the rise in spider mite numbers. As a result, its control has become a concern in many regions of the world, and it has been labeled the “most resistant species” in terms of the number of pesticides to which its population has developed resistance (Van Leeuwen et al., 2008). The most important factors contributing to such evolution in T. urticae are abundant offspring due to arrhenotoky parthenogenesis, concise life cycle, and detoxification genes. Therefore, mites (Gong et al., 2018); predatory insects (Calderwood et al., 2015); and entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) (Gámez-Guzmán et al., 2019) should be considered as potential alternatives to chemical pesticides for controlling T. urticae on a global scale.

Mite populations have been drastically reduced by entomopathogenic fungi in recent years, suggesting their potential utility in a biological control initiative. The most widely recognized pathogenic to many kinds of mites is Beauveria bassiana (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae), which is very successful at lowering mite populations. The use of fungus, B. bassiana, in bio-preparations is becoming popular worldwide (Yucel, 2021). Entomopathogenic fungi are commonly harmless to humans and without damage to the environment or non-target species.

Since the spread of infection is tied to the release of extracellular enzymes, during reproduction inside the host’s body, conidia produce various virulence factors known as extracellular enzymes, especially chitinases, along with proteolytic enzymes, which help to penetrate the host's epidermis and facilitate infection. The entomopathogenic fungi grow and feed on nutrients from the haemolymph process (Elawati et al., 2018). Pathogenic fungi were proven to be dangerous because they secreted enzymes that ate away at the cuticle. The choice of fungal strains is crucial to the efficacy of EPF as a biological control agent against mites or insects (Elhakim et al., 2020).

The current work aims to (i) identify entomopathogenic fungi from two-spotted spider mite and insect samples in Saudi Arabia and screen these fungal isolates for their ability to release lipase, protease, and enzymes (chitinase) that break down the cuticle of the two-spotted spider mite (ii) run a molecular identification of the isolated fungi, (iii) determine the biological factors in T. urticae at constant temperature on different host plants (tomato, eggplant, and pepper), (iv) verify pathogenicity of local B. bassiana isolates at different concentrations against motile stages of T. urticae under laboratory conditions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Local isolation of entomopathogenic fungi from TSSM and red palm weevil

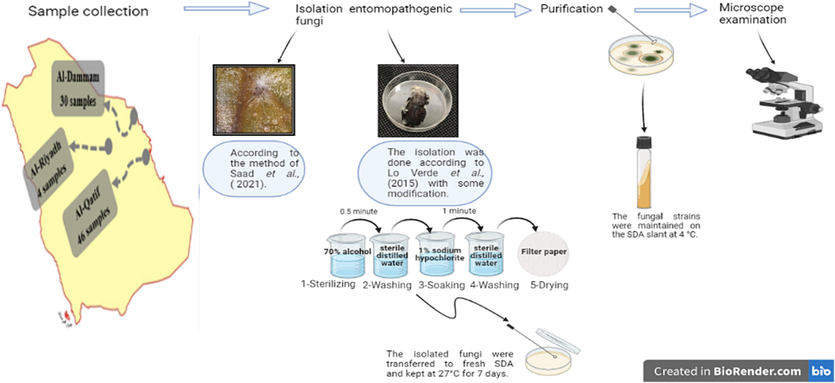

A total of 80 isolates, comprising 50 adult insect samples of Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (red palm weevil, RPW) and 30 adult mite samples of T. urticae (Koch), were obtained. The R. ferrugineus samples were collected from Riyadh and Qatif regions; and the T. urticae samples were collected from Dammam region. The infected samples were recognized according to the mycelial growth outside the sample’s body (Fig. S1). At each location, cadavers of naturally infected R. ferrugineus were collected and preserved in sterile Petri dishes. Once the samples arrived at the laboratory, fungi were isolated using the (Lo Verde et al., 2015) method with certain modifications. In brief, each sample was socked in 70% alcohol for half a minute.

to sterilize its surface, then washed with sterile distilled water. After one minute, the sample is rinsed in sterile distilled water and treated with 1% sodium hypochlorite. After that, we took pieces of each sample and put them on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) with yeast extract (Oxoid). The samples were kept in a 27 ± 2 °C incubator for seven days. After a time of incubation, a small inoculum of the growing mycelium from each sample was transferred into a new SDA plate using a sterilized needle. Cultures were checked daily for the presence of fungal colonies growth (Fig. 1). Once a colony grow it get transferred to SDA or Czapek Dox Agar medium (CZA, Oxoid) for purification (Yousef and Fouly, 2021).

Morphological identification of entomopathogenic fungi.

2.2 Collecting of T. urticae phytophagous mite

At the Agriculture Research and Biological Control Center of King Faisal University located in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia Tetranychus urticae mite individuals were found in the leaves of bean, eggplant, and cucumber plants grown in greenhouses. At Dammam city, in Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University's Basic and Applied Scientific Research Center mite samples were received after they were collected and transferred in plastic bags.

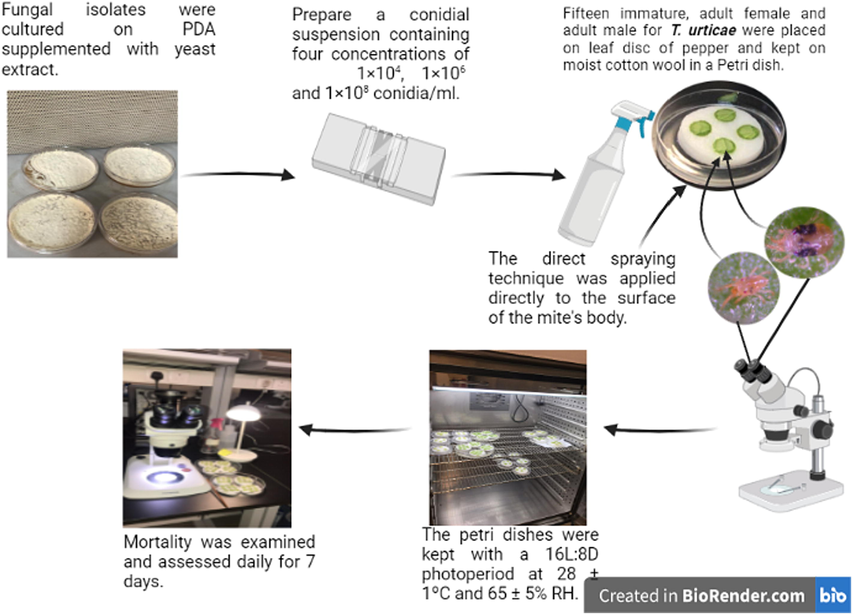

2.3 Preparation of fungal inoculum

The entomopathogenic fungi were cultivated on autoclaved potato dextrose agar, which was supplemented with yeast extract, using the following procedure: A solution was prepared by dissolving potato infusion (200 g/L), dextrose (20 g/L), yeast extract (20 g/L), and agar (20 g/L) in 1L of distilled water. The media were thereafter incubated under controlled conditions of darkness at a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C and relative humidity of 65 ± 5% for a period of 10–14 days to facilitate the development of conidia (Örtücü and Iskender, 2017).

The Neubauer-improved hemocytometer, manufactured in Germany, was used to ascertain the spore concentrations of 1 × 104, 1 × 106, and 1 × 108 (conidia/ml). The conidia were collected by scraping them from the surface cultures and afterwards suspended in 10 ml of sterile distilled water, with a ratio of 0.2 ml of Tween 80 per ml of water. This suspension was prepared in universal flasks containing glass pellets to prevent clumping of the conidia. Subsequently, the produced suspensions underwent filtration using three layers of muslin fabric in order to remove hyphae and conidia that were not well suspended. Subsequently, the spore suspensions were promptly used following their production (Sewify et al., 2015).Fig. 2.

Treatment of male and female Tetranychus urticae by Beaveria bassiana.

2.4 Tetranychus urticae developmental stages

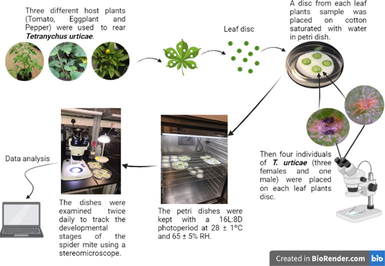

Tomato, eggplant, and pepper as host plants were used to determine how the host plant affected the biology and Life-table parameters of T. urticae. From each leaf sample, four discs were placed on a wet cotton on a petri dish. Then, four T. urticae individuals were placed in the petri dish on each leaf disc (three females and one male). The petri dishes were stored at 28 ± 1 °C and 65 ± 5% RH with a photoperiod of 16L:8D. Cotton was saturated with water every day, and dying leaves were replaced with new ones at regular intervals, so that the leaves would always look and smell fresh. The decaying leaves’ replacement was done until the most significant number of eggs (No. 90) were obtained. Eggs were monitored and TSSM stages were observed until they reached adulthood. The entire lifespan of T. urticae was tracked with twice-daily observations.

2.5 Reproduction, lifespan, and life tables of T. urticae

In this study, we used the same cultivars to assess T. urticae longevity and reproductive success. When the mites reached adulthood, two pairs (male and female) for mating occurrence were transferred to a new disc and kept together for the experiment using a 16L:8D photoperiod, 28 ± 1 °C, and 65 ± 5% relative humidity. Eggs were counted daily until all pairs in the experiment had died with maintaining the leaves' disc freshness condition. Using the developmental period of immature stages, the survival rate of immature females to adulthood, and the sex ratio of the progeny, the Birch (Birch, 1948) approach determined the life-table characteristics for each treatment group.

2.6 Molecular identification of fungi

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the isolated fungus using the Yeast/Bact Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The fungal isolate's 18S rRNA gene was then amplified using an absolute master mix (MoleQule-On, Auckland, New Zealand) with 10 µM of both 18S rRNA Forward (5′-GCTTAATTTGACTCAACACGGGA-3′) and Reverse primers (5′-AGCTATCAATCTGTCAATCCTGTC-3′) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was performed on the master mixes as follows: (a) a 10-minute initial denaturation at 95 °C; (b) 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 56 °C for 1.15 min, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min; and (c) a 5-minute final extension at 72 °C. The PCR amplicons were then electrophoretically separated on a 2% agarose gel (Alshammary et al., 2023). Following visual inspection of the PCR results, the amplicons were purified with the QI quick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Prior to 18S rRNA sequencing of isolated fungi, the purified PCR amplicons’ quantity and purity were measured using the Nanodrop 8000 V2.3.2 spectrophotometer. Using 3500 genetic analyzer, Sanger sequencing analysis was performed using the recent study (Alshammary et al., 2023) between 18S rRNA gene sequences of the fungal isolates. All of the fungus isolates' unprocessed 18S rRNA gene sequences were aligned in Bio Edit. The BLASTN program from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) was used to compare the obtained sequences to those in the GenBank database. When identity and query cover were between 98% and 100%, sequences were deemed to be significantly aligned.

2.7 Screening fungi for extracellular enzymes production

Lipase assay. The fungi were examined for their lipolytic activity using two agar mediums: phenol red (Triyaswati and Ilmi, 2020) and Tributyrin (TBA, Himedia) (Wadia and Jain, 2017). The phenol red agar medium was prepared by dissolving 0.4 g/L phenol red, 20 ml/L olive oil, 10 ml/L Tween 80, 1 g/L CaCl2 and 20 g/L Agar in 970 ml distilled water; pH was adjusted to 7. The TBA medium was prepared by dissolving 5.0 g/L Peptone, 3.0 g/L yeast extract, 15.0 g/L Agar, and 10.0 ml/L tributyrin glycerol tributyrate in 990 ml distilled water; pH was adjusted to 7.5. Both agar mediums were inoculated with fungi isolates and incubated for 7 days at 27 °C. After incubation, the diameter of formed halo zone around the fungal colony was measured (in mm) as an indicator of the lipolytic activity of the fungi.

Protease assay. Using Czapek Dox Agar medium, the fungi were screened for their proteolytic activity on skimmed milk according to (Ben Mefteh et al., 2019) procedure with some modifications. procedure with some modifications. In brief, the agar medium was prepared by stirring 2.5 g/L NaNO3, 1 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g/L KCl, 0.01 g/L FeSO4·7H2O, 30 g/L Sucrose, and 20 g/L Agar in 800 ml of distilled water. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 then sterilized at 121 °C in an autoclave. After sterilization, 200 ml/L skimmed milk was added to the slightly cooled medium before solidification in a fume hood cabinet. The Czapek Dox Agar medium was poured into sterile petri dishes. After cooling, fungi were inoculated and incubated for 7 days at 27 °C. After incubation, the halo zone diameter formed around the fungal colony was measured (in mm) as an indicator of the proteolytic activity.

Chitinase assay. Following (Homthong et al., 2016) with some modifications, we synthesized a wet colloidal chitin from the chitin of shrimp shells (Hi-Media). Moist colloidal chitin was prepared from the chitin of shrimp shells (Hi-Media) Following (Homthong et al., 2016) method with some modifications. Briefly in a 1000 ml beaker, 10 g of chitin powder was added softly to 200 ml concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) with continuous vigorous magnetic stirring for 3 h, where the solution became very viscous. With constant stirring, the solution was transferred into 1 L of cooled distilled water. The suspension was kept overnight under static conditions at 4 °C to facilitate better precipitation of colloidal chitin. The following day, chitin suspension was washed 10 times through cycles of centrifugation and precipitation at 4 °C. In the first washing cycle, the suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. Precipitate was then collected and washed initially with 1 N NaOH. The second cycle of washing was at 8000 rpm for 15 min and the precipitate was washed with tap water. The rest of the washing cycles were also with tap water but at 5000 rpm for 10 min instead; until the chitin suspension reached a pH of 5.5 to 7. The obtained moist colloidal chitin suspension was placed in a 100 ml glass beaker covered with two layers of aluminum foil and sterilized by chitin agar medium was prepared and used to screen the fungi chitinolytic activity. The agar was prepared according to (Chi, 2015) procedure, where 2.0 % of the prepared moist colloidal chitin was dissolved with 0.7 g/L K2HPO4, 0.3 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4·5H2O, 0.01 g/L FeSO4.7H20, 0.001 g/L ZnSO4, 0.001 g/L MnCl2, and 20 g/L Agar in 1000 ml of distilled water. The medium pH was adjusted to 7.0 ± 0.2. Fungi were inoculated and incubated for 7 days at 30 °C. After incubation, the clear zone diameter formed around the fungal colony was measured (in mm) to indicate the fungi chitinolytic activity.

2.8 Treatment of Tetranychus urticae with Beaveria bassiana

Fifteen adult females and males of T. urticae, were individually treated on a pepper leaf disc (3 cm in diameter) and maintained on a moist cotton-wool pad in a 15 cm Petri dish. Each plate has 6 duplicate tablets. Direct spray was delivered to the body surface of mites from each dosage concentration using a hand sprayer at 25–30 cm, and control duplicates were sprayed with water. After application, using a microscope counted live and dead mites every day for 7 days. Cadavers were designated “mycotic” if fungal growths occurred in damp Petri dishes after three days in the same conditions (Sewify et al., 2015) Fig. 2.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The ANOVA test analyzed the obtained data, and Tukey HSD compared the means (IBM Crop. Released, 2014 SPSS 22.0). The values are expressed as means ± standard error (SE). Moreover, T. urticae Life-table parameters were calculated using TWO SEX-MSChart (Murthy and Bleakley, 2012).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Isolation of host-associated fungal isolates

The collected 80 samples of insects and mites were showing disease symptoms (e.g., slow movement, the appearance of mycelium on the surface body, change in color and swelling of the individual). As a result, 8 fungal isolates were recovered from these samples collected from Dammam, Qatif, and Riyadh. Interestingly, a single isolate of Beauveria sp., Aspergillus sp., and Penicillium sp. were found on the RPW from Qatif. Whereas two Scopulariopsis species were found from the Riyadh RPW samples. On the other hand, three isolates of Fusarium spp. were obtained: two found on the RPW in Qatif and one on the TSSMs in Dammam (Table 1). Similarly, Qayyum et al (Qayyum et al., 2021) isolated 94 entomopathogenic and opportunistic from 225 cadavers of insects in Multan, Pakistan. Almost half of these were harbored by Coleoptera, an order of insects includes RPW.

Mites species

Location

Beauveria sp.

Scopulariopsis

sp.

Fusarium

sp.

Aspergillus

sp.

Penicillium

sp.

Total of isolates

Rhynchophorus

ferrugineus

Riyadh

0

2

0

0

0

2

Qatif

1

0

2

1

1

5

T. urticae

Dammam

0

0

1

0

0

1

Total

1

2

3

1

1

8

3.2 Identification of fungi

3.2.1 Morphological identification of fungi

Based on the culture morphology microscopic examination, the fungal isolated were identified as the following: Beauveria sp., Scopulariopsis spp., Fusarium spp., Aspergillus sp., and Penicillium sp. (Fig. S2). All fungal isolates were grown on the PDA media. Fungi colonies in covered Petri dishes grew rapidly during a 10-day period, changing from velvety white to creamy white. The mycelium of the isolates was dense and woollike, growing high into the air. In Petri dishes, the fungus developed an abundance of conidia in just 3 days (Fig. S2 and S3).

3.2.2 Fungi molecular detection

The genetic identification backed up the morphological one. Fungal isolates were identified by amplifying and sequencing the 18S rRNA gene, which gave a band length ranging from approximately 1226 base pairs (Fig. S4). Analysis of the 18S rRNA sequences revealed that our fungal strains belong to Beauveria bassiana, Fusarium equiseti, F. oxysporium, F. sp., Scopulariopsis brevicaulis 1, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis 2, Aspergillus sclerotiorum and Penicillium citrinum (Table 2). In Saudi Arabia, B. bassiana fungus was identified (Sayed et al., 2018) based on 18S rRNA, and their genetic diversity was studied in the Taif region. They also claimed that more study is required to see how effectively these isolates can combat major insect pests in Saudi Arabia. Also, in Saudi Arabia, fungi isolated from RPW at the Hail region were identified based on 18S rRNA as F. solani and F. proliferatum sharing 100 % sequence identity. They stated that the majority of species are saprophytic fungi that typically inhabit the soil. Nevertheless, some may be pathogenic fungi, such as certain Aspergillus spp, which could be beneficial for biological control.

Isolate identification

Isolates source

Accession number

Beauveria bassiana

R. ferrugineus

OR500626

Fusarium equiseti

R. ferrugineus

OR500521

Fusarium oxysporum

R. ferrugineus

–

Fusarium sp.

T. urticae

OR500625

Scopulariopsis brevicaulis 1

R. ferrugineus

OR500549

Scopulariopsis brevicaulis 2

R. ferrugineus

OR500608

Aspergillus sclerotiorum

R. ferrugineus

–

Penicillium citrinum

R. ferrugineus

OR500696

3.3 T. urticae Koch and the biology of TSSM

Tetranychus urticae was shown to have a five-stage life cycle (egg, larva, protonymph, deutonymph, and adult) on all the solanaceous plants examined under a 16L:8D photoperiod at temperatures of 28 ± 1 °C and relative humidity of 65 ± 5% RH (Fig. 2 and S5). These plants significantly altered the Life-table aspects of the species, including its growth, reproduction, and overall health. Previous findings by support these results on different host plants, tomato, eggplant, pepper, bean, and squash at 25 ± 1 °C, in addition to Awad (Awad et al., 2018) on tomato, eggplant, and pepper at 27 ± 4 °C, Mohamed (Mohamed et al., 2020) also, on tomato, eggplant, and pepper at 27 °C; moreover, a study (Praslička and Huszár, 2004) on Phaseolus vulgaris, Cucumis sativus and Capsicum annuum at different temperature 15, 30 and 35 °C.

3.3.1 Developmental period of T. urticae female

Tetranychus urticae females were grown at 28 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% RH, and 16L:8D photoperiod, and the findings are shown in Table 3 and Fig. S6. The average incubation period for T. urticae females ranged from 3.41 to 3.84 days on different solanaceous plants, tomato, eggplant and pepper (F2,67 = 5.756, P = 0.005). These findings are consistent with those of Awad (Awad et al., 2018), who found that the incubation period for T. urticae female eggs on solanaceous plants was (3.86–3.93 days) when kept at 27 ± 4 °C. Egg incubation periods ranged from 3.09 to 4.39 days, which was also considerably impacted by eggplant varieties. Also, the average stage of the female larval was 1.80, 2.33, and 2.96 days (F2,66 = 19.604, P = 0.000). These times are also extremely close to the results reported by Khodayari and Shalilvand (Khodayari and Shalilvand, 2021) for five types of pepper and by Razmjou (Razmjou et al., 2009) for five types of beans grown at 25 °C. The Tukey LSD test indicates that there is no significant difference between the columns that have the same letter.

T. urticae female (Stages)

Egg

Larvae

Protonymph

Deutonymph

Immatures

Life cycle

Host plant

(N = 21–25)

(N = 20 –25)

(N = 20–24)

(N = 18 –22)

(N = 18– 22)

(N = 18–22)

Tomato

3.42 ± 0.13b

1.80 ± 013b

2.25 ± 0.16a

2.16 ± 0.12a

5.94 ± 0.15c

9.44 ± 0.14c

Eggplant

3.41 ± 0.10b

2.33 ± 0.14c

2.33 ± 0.10a

2.25 ± 0.09a

6.80 ± 0.17b

10.20 ± 0.18b

Pepper

3.84 ± 0.07a

2.96 ± 0.10a

2.66 ± 0.13a

2.22 ± 0.11a

7.59 ± 0.17a

11.54 ± 0.18a

3.3.2 Developmental period for T. urticae male

Results in Table 4 and Figure S7 reveal that males followed the same pattern as females, under shorter time periods. In addition, male duration and longevity varied according to the host plants. The average incubation time for males was 2.89 to 3.69 days (F2,42 = 14.552, P = 0.000). These findings are consistent with those observed by Mohamed (Mohamed et al., 2020) for male T. urticae on the leaves of three solanaceous plants (eggplant, tomato, and pepper) at 27 °C (3.36 to 3.86 days). Whereas the average stage of the male larval stages was 1.50, 1.94, and 2.92 days (F2,42 = 32.006, P = 0.000), and the male protonymph lasted 1.86, 1.88, and 2.69 days (F2,41 = 7.802, P = 0.001) and the male deutonymph duration was 1.64, 1.93, and 2.00 days (F2,39 = 2.382, P = 0.106) on tomato, eggplant, and pepper, respectively. These results are relatively like Abou-Elella et al (Abou-Elella and Abdel-Khalek, 2020); where the male larval stages were (1.17–3.67 days), and the male protonymph lasted (1.00–2.33 days), and the male deutonymph duration was (1.33–2.25 days) on four pea and bean cultivars. The male total immature period averaged 5.00, 5.53, and 7.62 days (F2,39 = 34.647, P = 0.000) on tomato, eggplant, and pepper, respectively. These findings corroborate those of Mohamed (Mohamed et al., 2020) who found that T. urticae males spent a total of 5.16 days in the immature stage when fed eggplant, 5.20 days when fed tomato, and 7.20 days when fed pepper. The Tukey LSD test indicates that there is no significant difference between the columns that have the same letter.

Stage

Egg

Larvae

Protony

Deutony

Total

Life

Longevity

Lifespan

(N = 21-

(N = 20 –

mph

mph

Immature

cycle

(N = 13–

15)(N = 13-

Host plant

25)

25)

(N = 20––24)

(N = 18

–22)(N = 18– 22)

(N = 18– 22)

15)

Tomato

3.64 ± 0.1

1.50 ± 0.

1.86 ± 0.

1.64 ± 0.

5.00 ± 0.27

7.64 ± 0.

10.14 ± 0.4

19.92 ± 0

3b

13c

14b

13a

B

28b

1b

0a

Eggplant

2.89 ± 0.1

1.94 ± 0.

1.88 ± 0.

1.93 ± 0.

5.53 ± 0.16

8.33 ± 0.

11.25 ± 0.3

20.20 ± 0

3b

09b

18b

11a

B

18b

3a

6a

Pepper

3.69 ± 0.1

2.92 ± 0.

2.69 ± 0.

2.00 ± 0.

7.62 ± 0.24

11.31 ± 0

8.54 ± 0.68

17.79 ± 0

3a

13a

13a

11a

A

.30a

b

2b

3.4 Female T. urticae longevity and life duration

The effects of temperature (28 ± 1 °C), relative humidity (65 ± 5%), and photoperiod (16L:8D) on the reproductive phases, longevity, and life span of T. urticae females are shown in Table 5 and Fig.S8. The pre-oviposition period on pepper was 1.72 days, on tomato it was 2.22 days, and on eggplant it was 2.55 days (F2,57 = 9.922, P = 0.000). Comparable results were found when using tomato (1.07–1.15 days), eggplant (1.18–1.9 days), pepper (1.08–2.50 days), cucumber (0.79–1.13 days), and beans (1.26–1.44) as the host plants. The oviposition period averaged 7.90 days, 9.50 days, and 9.55 days on pepper, tomato, and eggplant, respectively (F2,57 = 4.008, P = 0.024). The Tukey LSD test indicates that there is no significant difference between the columns that have the same letter.

Stage

Preoviposition

Oviposition

Postoviposition

Longevity

Life span

Female

Host plantperiod (N = 18–22)

period (N = 18–22)

period (N = 18–22)

(N = 18–22)

(N = 18–22)

sex

ratio (%)

Tomato

2.22 ± 0.10a

9.50 ± 0.25ab

2.00 ± 0.14a

13.72 ± 0.23a

23.16 ± 0.29a

60.00 %

Eggplant

2.55 ± 0.11a

9.55 ± 0.33a

2.15 ± 0.10a

14.25 ± 0.44a

23.45 ± 0.47a

57.14%

Pepper

1.72 ± 0.20b

7.90 ± 0.65b

0.81 ± 0.33b

10.40 ± 0.54b

21.86 ± 0.61a

68.29%

The obtained results were less or more than the values obtained in previous studies on different solanaceous plants. Mohamed (Mohamed et al., 2020) were (7.43 days) on eggplant, (5.63 days) on tomato and (3.00 days) on pepper (Awad et al., 2018) (11.13 days) on eggplant, (9.93 days) on tomato and (8.61 days) on pepper (Nasr et al., 2019), was (10.33 days) on tomato due to the quality of the host plant can affect the fecundity rate of their herbivores, maybe due to its chemical composition such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (Helle and Sabelis, 1985).

3.4.1 Fecundity and daily egg of T. urticae female

Even among the host plants, there was a wide range in TSSM fertility. Tomatoes had the highest fertility at 46.16 eggs per female per day (a rate of 4.91 eggs), followed by eggplant at 38.05 eggs per female per day (a rate of 3.98 eggs), and finally pepper at 16.40 eggs per female per day (a rate of 1.99 eggs) (Table 6 and Fig. S9). Tetranychus urticae has been shown to have varying fecundity rates depending on the host plant, where it was (61.56, 61.13, 75.72 eggs/female) on eggplant and (59.77, 51.86, 52.36, and 85–276 eggs/female) on tomato, at daily rates of (5.03,5.49, and 10.19 eggs/female/day) (Awad et al., 2018; Mohamed et al., 2020). The Tukey LSD test indicates that there is no significant difference between the columns that have the same letter.

Stage

Host plant

Fecundity (N = 18 – 22)

Daily fecundity

(eggs/female/day) (N = 18 – 22)

Tomato

46.16 ± 1.57a

4.91 ± 0.19a

Eggplant

38.05 ± 1.67b

3.98 ± 0.12b

Pepper

16.40 ± 2.03c

1.99 ± 0.17c

3.5 Life-table parameters of T. urticae

Laboratory testing of T. urticae on solanaceous plants was conducted at 28 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% RH, and 16L:8D photoperiod (Table 7). Infestations of TSSM varied in their GRR between solanaceous plants, where the highest values were recorded with spider mites reared on tomato as (29.75 ± 3.79 eggs), followed by eggplant (24.37 ± 3.29 eggs), while the lowest values were obtained on pepper (13.75 ± 0.0114 eggs). The Tukey LSD test indicates that there is no significant difference between the columns that have the same letter.

Stage

Host plant

The mean generation time (T) in days

The doubling time (DT) days

Finite rate of increase (λ)

The intrinsic rate of natural increase (rm)

Net reproductive rate (Ro)

The gross reproductive rate (GRR)

Tomato

16.22 ± 0.20c

3.59c

1.215 ± 0.013b

0.192 ± 0.011a

23.74 ± 3.97a

29.75 ± 3.79a

Eggplant

17.09 ± 0.26b

4.08b

1.184 ± 0.012a

0.169 ± 0.010b

18.02 ± 3.01b

24.37 ± 3.29b

Pepper

18.16 ± 0.34a

5.60a

1.131 ± 0.011b

0.123 ± 0.010b

9.5 ± 1.75c

13.75 ± 0.01c

3.6 Screening of fungal isolates for enzymes

3.6.1 Lipolytic activity

On phenol red agar media, lipase activity was only detected in Beauveria bassiana. The yellow halo created surrounding the colony measured (39.83 mm) in diameter (Table. 8 and Fig. S10). Conversely, the highest lipase activity was found on tributyrate medium in Fusarium sp. 3 (67.33 mm) and Penicillium citrinum (64.16 mm), followed by F. oxysporum (59.75 mm), B. bassiana (56.58 mm), Scopulariopsis brevicaulis 1 (55.75 mm), F. equiseti (54.58 mm), and (Table. 8 and Figs. S11). Since fungi are well known for being favored sources of lipase, other research' findings have been inconsistent. Wadia (Wadia and Jain, 2017) showed that Alternaria sp. and Aspergillus flavus were better at producing extracellular lipase than Penicillium sp., Trichoderma sp., and A. niger. Mezzomo (Mezzomo et al., 2019) studied the ability of a group of Fusarium spp. The Tukey LSD test indicates that there is no significant difference between the columns that have the same letter. ND: Not determinate.

Enzyme activity diameter (mm) ± S. E

Isolate

Phenol redLipase

TributyrinProtease

Chitinase

Beauveria bassiana

39.83 ± 0.49

56.58 ± 0.52d

35.16 ± 0.38f

53.41 ± 0.49

Fusarium equiseti

ND

54.58 ± 0.35e

80.00 ± 0.00a

ND

Fusarium oxysporum

ND

59.75 ± 0.44c

76.83 ± 0.60b

ND

Fusarium sp.

ND

67.33 ± 0.57a

ND

ND

Scopulariopsis brevicaulis 1

ND

55.75 ± 0.38e

70.41 ± 2.10c

ND

Scopulariopsis brevicaulis 2

ND

51.16 ± 0.60f

68.41 ± 0.15d

ND

Aspergillus sclerotiorum

ND

42.08 ± 0.89 g

79.41 ± 0.37a

ND

Penicillium citrinum

ND

64.16 ± 0.61b

40.41 ± 0.20e

ND

3.6.2 Proteolytic activity

The highest protease activity was recorded on skimmed milk agar medium in Fusarium oxysporum (80.00 mm), Aspergillus sclerotiorum (79.41 mm), and F. equiseti (76.83 mm), followed by Scopulariopsis brevicaulis 1 (70.41 mm), and S. brevicaulis 2 (68.41 mm). In contrast, the lowest protease activity was observed in Penicillium citrinum (40.41 mm) and Beauveria bassiana (35.16 mm) (Table. 8 and Fig S12). Pathogenesis of entomopathogenic fungi often relies heavily on proteases. Elhakim et al (Elhakim et al., 2020) found a positive correlation between protease activity and the virulence of fungal isolates; they found that an isolate from Beauveria spp. with the highest proteolytic activity was more infectious to the red spider mite T. urticae. EPF secretes enormous amounts of proteases, which can breakdown protein and peptide compounds after lipolysis of the epicuticle by lipases and esters; the protease then helps cleave the peptide bonds of cuticle proteins, increasing pathogenicity against target insects. Then, peptides (arylamides) and amino acid exopeptidases breakdown the soluble proteins, providing resources for the fungi and possibly hastening their growth in the insects (Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2014).

3.6.3 Chitinolytic activity

No chitinolytic activity was observed in all tested isolates except for isolate Beauveria bassiana (53.41 mm) (Table 8 and Fig. S13). The obtained results agree with a study conducted (Chui-Chai et al., 2012) on 14 isolates of Beauveria spp. examined to produce chitinase on colloidal chitin agar and found 8 positive isolates. It was also discovered that chitinase activity tends to increase following the maximum protease activity, and that all eight positive isolates that produced chitin enzyme also produced protease from day one of cultivation. They were then chosen for their ability to manage the diamond back moth, Plutella xylostella second-instar larvae. One of the previous studies (Örtücü and Iskender, 2017) found that the ability of B. bassiana isolates to produce chitin enzyme on colloidal chitin agar plates where the isolate was reported that give the highest degrading activity to chitin was more virulent against T. urticae. After protease activity, chitinase plays a larger role in the hydrolysis of chitin, the primary component of insect cuticles, and completes the process of integument penetration and disintegration (Pusztahelyi and Pócsi, 2014).

3.7 The efficacy of infection with the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

on males and females of the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae was evaluated under laboratory conditions at a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C with a relative humidity of 65 ± 5% and a photoperiod of 16:8 h (L:D). Three concentrations (1 × 104, 1 × 106, and 1 × 108 conidia/ml) of B. bassiana were used (Table 9). The ability of the fungus to kill the mites was very high. At all concentrations, the fungus completely killed all individuals. Many researchers have obtained results similar findings have been reported by Al Alawi (Al-Alawi, 2019) and Irigarai et al., (Irigaray et al., 2003) in T. urticae, as well as in other arthropods, such as the spider mite Tetranychus evansi (Wekesa et al., 2006), and tick species (Samish et al., 2001; Gindin et al., 2002). The Tukey LSD test indicates that there is no significant difference between the columns that have the same letter.

Conc. (conidia/ml)

female

male

Means ± SE

Reduction

Means ± SE

Reduction

Control

7.83 ± 1.68b

4.33 ± 1.64b

1 × 104

15.00 ± 0.00a

100.00 %

15.00 ± 0.00a

100.00 %

1 × 106

15.00 ± 0.00a

100.00 %

15.00 ± 2.50a

100.00 %

1 × 108

15.00 ± 0.00a

100.00 %

15.00 ± 0.00a

100.00 %

4 Conclusion

T. urticae is a major agricultural pest. Saudi greenhouses lose crops. This pesticide-resistant bug causes health issues and financial losses; thus, a safe and ecologically friendly alternative is needed. Predatory and entomopathogenic fungi control TSSM-infected plants. On tomato, eggplant, and pepper plants, T. urticae growth, reproduction, and Life-table were examined. Pepper reproduced less T. urticae than eggplant and tomato. Insect and mite samples from around Saudi Arabia yielded eight fungi. They were genetically identified and tested for lipase, protease, and chitinase, which destroy the two-spotted spider mites’ cuticle. The present investigation identified Beauveria bassiana as the most promising and primary choice for implementing biological control against the red two-spotted mite. This selection was based on its superior ability to generate lipase, protease, and chitinase enzymes, surpassing the capacities of other isolates obtained in the study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Biology and Life-table analysis of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) on different common pea and bean cultivars. Persian Journal of Acarology.. 2020;9(2):181-192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of Jordanian isolates of Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin and their interaction with essential plant oils when combined for the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch control. Adv. Environ. Biol.. 2019;13:4-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence from genetic studies among variants rs2107538 in the CCL5 gene and Saudi patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences.. 2023;103658

- [Google Scholar]

- Dissecting the Molecular Role of ADIPOQ SNPs in Saudi Women Diagnosed with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines.. 2023;11(5):1289.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development and reproduction of the two-spotted red spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch as influenced by feeding on leaves of three solanaceous vegetable crops under laboratory conditions. J. Entomol.. 2018;15(2):69-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Response surface methodology optimization of an acidic protease produced by Penicillium bilaiae isolate TDPEF30, a newly recovered endophytic fungus from healthy roots of date palm trees (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Microorganisms. 2019;7(3):74.

- [Google Scholar]

- The intrinsic rate of natural increase of an insect population. J. Anim. Ecol.. 1948;15–26

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey of northeastern hop arthropod pests and their natural enemies. Journal of Integrated Pest Management.. 2015;6(1):18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chi H. TWOSEX-MSChart: a computer program for the age-stage, two-sex Life-table analysis. Available on: http://140120. 2015;197.

- Insecticidal activity and cuticle degrading enzymes of entomopathogenic fungi against Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) J. Nat. Sci.. 2012;11(1):147-155.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological control methods for agricultural mites: A review. Agric. Rev.. 2023;44(1):12-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elawati N, Pujiyanto S, Kusdiyantini E, editors. Production of extracellular chitinase Beauveria bassiana under submerged fermentation conditions. Journal of Physics: Conference Series; 2018: IOP Publishing.

- Virulence and proteolytic activity of entomopathogenic fungi against the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control.. 2020;30(1):1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential of a Cladosporium cladosporioides strain for the control of Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) under laboratory conditions. Agronomía Colombiana.. 2019;37(1):84-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- The susceptibility of different species and stages of ticks to entomopathogenic fungi. Exp. Appl. Acarol.. 2002;28:283-288.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preference and performance of the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) on strawberry cultivars. Exp. Appl. Acarol.. 2018;76:185-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of chitinase from soil fungi. Paecilomyces sp. Agriculture and Natural Resources.. 2016;50(4):232-242.

- [Google Scholar]

- The entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana and its compatibility with triflumuron: effects on the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae. Biol. Control. 2003;26:168-173.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological responses of T. urticae to five pepper cultivars at two phenological stages of host plants. Syst Appl Acarol. 2021;26(10):1927-1939.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenicity bioassays of isolates of Beauveria bassiana on Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Pest Manag. Sci.. 2015;71(2):323-328.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) feeding and gold fleck damage on tomato fruit. Crop Prot.. 2012;42:24-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressiveness of Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium solani isolates to yerba-mate and production of extracellular enzymes. Summa Phytopathol.. 2019;45:141-145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative biology of Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) on three solanaceous plants and the predator Amblyseius hutu (Prichard & Baker) Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a potential biological control agent for Tetranychus urticae. Journal of Plant Protection and Pathology.. 2020;11(9):473-476.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simplified Method of Preparing Colloidal Chitin Used For Screening of Chitinase- Producing Microorganisms. Internet J. Microbiol.. 2012;10(1):1-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular-Based Taxonomic Inferences of Some Spider Mite Species of the Genus Oligonychus Berlese (Acari, Prostigmata, Tetranychidae) Insects.. 2023;14(2):192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Host Plant on the Biological Aspects and Life-table Parameters for Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences A, Entomology.. 2019;12(6):75-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of control potentials and enzyme activities of Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vull. isolates against Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) Trakya University Journal of Natural Sciences.. 2017;18(1):33-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of temperature and host plants on the development and fecundity of the spider mite Tetranychus urticae (Acarina: Tetranychidae) Plant Prot. Sci.. 2004;40(4):141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chitinase but N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase production correlates to the biomass decline in Penicillium and Aspergillus species. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung.. 2014;61(2):131-143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diversity and correlation of entomopathogenic and associated fungi with soil factors. Journal of King Saud University-Science.. 2021;33(6):101520

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative population growth parameters of the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae), on different common bean cultivars. Systematic and Applied Acarology.. 2009;14(2):83-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenicity of entomopathogenic fungi on different developmental stages of Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) J. Parasitol.. 2001;87:1355-1359.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enzymes of entomopathogenic fungi, advances and insights. Advances. Enzyme Research.. 2014;2(02):65-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, identification, and molecular diversity of indigenous isolates of Beauveria bassiana from Taif region, Saudi Arabia. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control.. 2018;28:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Using a Biological Control Method For Controlling Red Spider Mite. Egypt Acad. J. Biol. Sci.. 2015;7:115-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- Triyaswati D, Ilmi M. Lipase-producing filamentous fungi from non-dairy creamer industrial waste. 2020.

- Mitochondrial heteroplasmy and the evolution of insecticide resistance: non-Mendelian inheritance in action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2008;105(16):5980-5985.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, screening and identification of lipase producing fungi from oil contaminated soil of Shani Mandir Ujjain. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci.. 2017;6(7):1872-1878.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae on mortality, fecundity and egg fertility of Tetranychus evansi. J. Appl. Entomol.. 2006;130:155-159.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multiple acaricide resistance and underlying mechanisms in Tetranychus urticae on hops. J. Pest. Sci.. 2019;92:543-555.

- [Google Scholar]

- Side effect of indigenous entomopathogenic fungi on the predatory mite, Cydnoseius negevi (Swirski and Amitai)(Acari: Phytoseiidae) Journal of Plant Protection and Pathology.. 2021;12(3):215-223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of local isolates of Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin on the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae (Koch)(Acari: Tetranychidae) Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control.. 2021;31:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102910.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: