Translate this page into:

EGFR targeting of [177Lu] gold nanoparticles to colorectal and breast tumour cells: Affinity, duration of binding and growth inhibition of Cetuximab-resistant cells

⁎Corresponding author at: Translational Radiobiology Group, Oglesby Cancer Research Centre, University of Manchester, Wilmslow Road, Manchester M20 4GJ, United Kingdom. tim.smith@manchester.ac.uk (Tim A.D. Smith)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objective

Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) is a systemic therapy currently used in the treatment of patients with lymphoma. RIT complexes consist of a targeting molecule, commonly an antibody, radionuclide chelates and a linker which can be a nanoparticle platform. Nanoparticles facilitate the attachment of multiple radionuclides and targeting groups to a single complex. Here the target affinity, duration of target association and inhibition of colony formation of Cetuximab-resistant tumour cells with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs were investigated. Dose distribution in xenografts derived from EGFR-overexpressing cells was also determined.

Methods

Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs were generated by functionalising 15nm AuNPs with the chelator DOTA and Cetuximab and radiolabelling with 177LuCl3. KDis, a measure of affinity, was determined by competitive binding to EGFR expressing cells. Radio-sensitivity was determined in EGFR expressing tumour cells including the Cetuximab resistant cell line HCT116 using a colony formation assay. Dose distribution was measured in sections from xenografts grown in nude mice using autoradiography.

Results

KDis for the complex binding to EGFR on MDA-MB-468 cells was 20 nM. Loss of cell associated [177Lu] activity was biphasic with loss of about 50% of activity in about 4 h. Remaining activity dissociated over a period of about 4 days. HCT8 and MDA-MB-468, but not HCT116 cells were sensitive to the growth inhibitory effect of Cetuximab. However, treatment with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs inhibited colony formation in all 3 cell lines. Dose distribution across sections from xenografts was found to demonstrate a co-efficient of variation of 15%.

Conclusion

Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs demonstrate high affinity for EGFR and could be an effective treatment for Cetuximab-resistant colorectal cancer cells. A strategy involving pre-treatment with receptor targeted[177Lu] to improve RIT therapeutic ratios has the potential to enhance clinical outcomes.

Keywords

Gold nanoparticles

EGFR

Cetuximab

Targeted radiotherapy

Xenografts

177Lu

1 Introduction

Many cancer patients present either with evident secondary (metastatic) disease or will develop metastasis (Redig and McAllister, 2013). Whilst external beam radiotherapy is an effective treatment for many primary cancers and regional metastases, distant metastases (Li et al., 2017) are currently treated with chemotherapy. However metastatic cancer cells almost always develop resistance to chemotherapy (Hammond et al., 2016).

Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) involves administering intravenously, targeted conjugates carrying cytotoxic radionuclides which seek out primary tumours and metastases. Agents utilised in RIT are composed of a targeting moiety such as an antibody and a linker or nanoparticle platform to which the targeting moiety and the radionuclides can be attached. Nanoparticles utilised as carriers are a diverse group of molecules which include dendrimers (Trembleau et al., 2011), quantum dots (Ni and Cd) (Bentolila et al., 2009), TiO2 (Cheyne et al., 2011) and Au colloid (Dziawer et al., 2017). Nanoparticles can carry multiple radionuclides to deliver radiation dose. These include 18F for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging or alpha and beta-emitters such as 90Y and 177Lu for therapy. Poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers are highly biocompatible, but they are heat labile so not suited to radiolabelling with metal chelators that require high temperatures to facilitate chelation e.g. DOTA chelation of 177Lu and 90Y which require heating to 80 °C for at least 15 min. Whilst toxicological considerations preclude the translatability of some inorganic nanoparticles e.g. quantum dots into the clinic, Au nanoparticles are attractive as they are non-toxic to cells when suitably surface coated (Alkilany and Murphy, 2010; Rosi et al., 2006), are commercially available and readily functionalised.

Although nanoparticles are preferentially retained by tumour tissue due to the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect (Lu et al., 2018), this passive targeting is greatly enhanced by active targeting with antibodies or other affinity molecules (Lu et al., 2018). Abnormal expression of cell surface growth factor receptors is common in many tumours and can be exploited for targeting anticancer agents. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in several solid tumour types including most colorectal cancers (Cuneo et al., 2015) and triple negative breast cancer (Nakai et al., 2016), a particularly difficult breast cancer subtype to treat. Cetuximab, a chimeric EGFR-targeting antibody, is used to treat patients with EGFR-overexpressing cancers including metastatic colorectal cancer. Cetuximab binding to the EGFR blocks the binding of the natural ligand EGF resulting in down regulation of MAPK signalling pathways downstream of the receptor (Linklater 2016). However, tumours with Kras mutations upregulate MAPK signalling and are consequently resistant to Cetuximab (Linklater et al., 2016).

It has previously been shown that [177Lu] targeted to the EGFR can induce growth inhibition in a head and neck xenograft (Liu et al., 2014). Here the efficacy of Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs (Cabello et al., 2018) to inhibit colony formation by breast and colorectal cancer cells including a Kras mutant colorectal cancer cell line was examined. Receptor affinity, rate of loss of incorporated [177Lu] and dose distribution homogeneity in sections of xenografts were also determined.

2 Methods

2.1 Fabrication of Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs

Preparation and radiolabelling of Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs was carried out as described previously (Cabello et al 2018). In brief, AuNP (15 nm) (Stratech, UK) were functionalised by incubation with orthopyridyldisulfide-polyethylene glycol-succinimidyl valerate (OPSS-PEG (5KDa)-SVA) and OPSS-PEG (3.5KDa)-DOTA linkers followed by OPSS-PEG(2KDa) to fill in any remaining non-coated surface regions. After washing steps to remove unattached linkers the surface coated AuNPs (1012 particles with a mass of 2 × 10−16 g) were radiolabelled by heating with [177Lu]-LuCl3 (10 MBq) in acetic acid. Radiolabelled AuNPs were then incubated with Cetuximab in NaHCO3 (pH7.4) to facilitate covalent bonding to SVA followed by washing steps to remove non-conjugated Cetuximab.

2.2 Cells and EGFR expression

Colorectal (HCT-8, HCT116, SW620) and breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-468) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (LGC standards, UK). Cells were maintained in 80 cm2 tissue culture flasks in Dulbecco Modified Eagle medium (Sigma-Aldrich UK) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (Gibco) and Penicillin (10,000 units/ml)/Streptomycin (10,000 µg/ml) (Gibco) until confluent then passaged 1:10. We have previously (Cabello et al 2018) demonstrated the levels of EGFR expression in each of these cell lines: MDA-MB-468 – high; HCT8 and HCT116 - intermediate and SW620 negative.

2.3 Rate of loss of [177Lu] by cells pre-incubated with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs

Previous studies have shown that intravenously administered NPs are rapidly cleared from the blood stream typically within 2–4 h (Chiarelli et al., 2017; Satterlee et al., 2015; Frellsen et al., 2016). To simulate the in vivo situation MDA-MB-468 tumour cells were incubated for 4 h with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs, washed with non-radioactive medium and incubated for up to 4 days with non-radioactive medium. For these experiments, cells (1 × 106) were seeded in 25 cm2 tissue culture flasks from a confluent 80 cm2 flask and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified CO2:air (5%:95%) mixture in a CO2 incubator (Heraeus Hera 150) until 75% confluent. Medium was replaced with fresh medium containing Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs (37KBq) for 4 h then washed and incubated with fresh medium. To determine the rate of loss of cell-associated activity radioactivity was determined in 10ul samples of medium taken at 15, 30, 60 min and 2, 4, 6, 20, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h time points during the incubation. Samples were placed in scintillation vials containing 1 ml of Ultima Gold scintillation fluid (Perkin-Elmer, UK) and radioactive counts measured on a Hewlett-Packard 2100 Tricarb scintillation counter (Hewlett-Packard, UK).

2.4 Protein assay

The NaOH was then neutralised by addition of 100 µl of HCl (1 M) and protein content determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma-Aldrich UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5 Cytotoxic assays

2.5.1 Cetuximab sensitivity by MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide) assay

A suspension of cells was prepared from a confluent flask of cells using trypsin. After addition of medium, cells were counted using a haemocytometer and a cell suspension of 10,000 cells/ml was prepared. Cells were added to columns 2–10 of a 96 well plate (except rows A and H to which 200 µl of H2O was added). Media only was added to column 11. The plate was incubated overnight then the cells were treated by addition of 100 µl of medium to each well containing Cetuximab (0.4–50 µg/ml) in increasing concentration from column 3–10. Drug-free medium only was added to column 1. The plates were incubated for 4 days at 37 °C, the medium removed and 100 µl of medium containing MTT (0.5 mg/ml) added. After 1–2 h (when the cells had become dark purple in colour) medium was discarded. One hundred µl of DMSO was added per well, the plate was agitated, and absorbance measured using a 540 nm filter in a plate reader (Thermo Labsystems Multiskan Accent) using Agilent software. After correcting for background (medium only) the results were expressed as a percentage of absorbance in wells in column 2 (no treatment).

2.5.2 Clonogenic assay

The clonogenic assay was performed as described previously (Smith et al., 2019). A suspension of cells was prepared as for the MTT assay with cell density of 1500 cells/ml. Cell suspension (1 ml) was added to each well of a 6 well plate and the cells left overnight at 37 °C. Medium was carefully removed from each well and 1 ml of medium was added either without or with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs (typically 2.8 MBq) or with [177Lu]-DOTA (2.8 MBq) which is not taken up by cells. The 3 controls and treated cells were randomly assigned (so that the reader was unaware which had been treated). The medium was removed after approximately 4 h and the cells were washed 2x by gentle addition and removal of 1 ml of medium. In the case of cells incubated with the non-targeted [177Lu]-DOTA, all the activity was washed away by the washing step. Two ml of Medium was then added to each well and the plates incubated at 37 °C. After 6 (HCT8) to 11 days (MDA-MB-468) colonies of 50 cells or more were counted manually under a microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS100 inverting microscope). For this purpose, a 9-region grid was drawn on each well with a fine tip marker. The size of a 50 cells colony was first checked at 100x magnification after which colonies of 50 cells or more were counted in each of the 9 regions of a grid at 40x magnification. The procedure was repeated for each well at the corresponding field of view for each region. After colony counting the medium was removed and MTT added to each well to determine total cell number in each well.

2.6 Bio-distribution and dose-distribution in xenografts

Xenografts were established from MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells by sub-cutaneous injection of 107 cells in 0.1 ml of PBS into the flank of 3 anaesthetised female Balb/c nude mice. All experiments were carried out under UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, UK Home Office regulations. Tumours were permitted to grow to a maximum diameter of 15 mm. Mice, under anaesthesia, were injected into the tail vein with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs (1 MBq in 100 µl). After 4 h the mice were anaesthetised, 1 ml of blood removed by cardiac puncture and the mice immediately killed by cervical dislocation. Tumour was removed, cut in two, and one piece was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The other half was weighed and dissolved in NaOH (1 M). Liver, spleen, lung, kidney and heart were harvested, weighed and dissolved in NaOH (1 M). After neutralisation, scintillation fluid (Ultima Gold – Perkin Elmer UK) was added and radioactivity in each sample determined and normalised to CPM/g tissue/injected activity (1 MBq). The frozen tumour was sectioned into 10, 20 and 50 µm sections using a cryostat. The tumour sections were subject to autoradiography, alongside a set of standards prepared by serial dilution of a known activity of [177Lu] LuCl3, for 1 h using BAS storage phosphor screen (GE, UK). The screen was read on a fluorescent image analyser (Fujifilm, Japan) set on the highest resolution (50 um).

2.7 Determination of dose heterogeneity

The image was divided into pixels (50 × 50 µm) and the grey scale intensity converted to numerical values. The mean and SD intensity values were then calculated for each section. A background area comprised of ∼ 1000 pixels was generated by automatically finding pixels between 3 and 15 pixels distance of the edge of each section. Background correction was carried out by subtraction of the mean activity of the background from the mean intensity of the section. Standard deviation (SD) was background corrected for each section using the formula: SDcor = SQRT((SDsec)2 − ((SDbgd)2).

SDbgd was determining from a 100 × 100 pixel region of interest a homogeneous part of the film. Coefficient of variation was then determined by dividing SD by mean × 100 for each section and reported a measure of dose heterogeneity.

3 Results

3.1 Dissociation constant for binding to tumour cells

Fig. 1 shows cell associated [177Lu] of cells incubated with Cetuximab-[177Lu]-NP with increasing concentrations of Cetuximab (expressed as log10 on the x-axis) as a fraction of cells only incubated with Cetuximab-[177Lu]-NP. An increase in uptake was associated with concentrations of Cetuximab between about 0.05 nM and 12 nM, higher concentrations competing with Cetuximab-[177Lu]-NP. The KDis was calculated based on the B/Bo of 0.5 and was found to be 19.95 nM.![Cell associated [177Lu] of MA-MB-468 cells incubated with Cetuximab-[177Lu-NP] (10KBq) plus increasing concentrations (0–133 nM) of non-radioactive Cetuximab. The values are expressed as log10 on the x-axis as a fraction of uptake by cells incubated with Cetuximab-[177Lu-NP] in the absence of non-radioactive Cetuximab. (bars = SD from 5 determinations).](/content/185/2021/33/7/img/10.1016_j.jksus.2021.101573-fig1.png)

Cell associated [177Lu] of MA-MB-468 cells incubated with Cetuximab-[177Lu-NP] (10KBq) plus increasing concentrations (0–133 nM) of non-radioactive Cetuximab. The values are expressed as log10 on the x-axis as a fraction of uptake by cells incubated with Cetuximab-[177Lu-NP] in the absence of non-radioactive Cetuximab. (bars = SD from 5 determinations).

3.2 Release of [177Lu] from cells pre-incubated with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs

Cell associated activity was determined at various times and plotted against time (Fig. 2). The rate of loss of activity showed a biphasic relationship with time.![Rate of loss of cell associated activity. MBA-MB-468 cells were incubated with Cetuximab-[177Lu] for 4 h then washed and incubated in non-radioactive medium for 0–96 h. Cells were sampled at intervals, centrifuged and cell-associated activity determined. Remaining cell associated [177Lu] activity as a % of cell-associated [177Lu] before incubation in non-radioactive medium.](/content/185/2021/33/7/img/10.1016_j.jksus.2021.101573-fig2.png)

Rate of loss of cell associated activity. MBA-MB-468 cells were incubated with Cetuximab-[177Lu] for 4 h then washed and incubated in non-radioactive medium for 0–96 h. Cells were sampled at intervals, centrifuged and cell-associated activity determined. Remaining cell associated [177Lu] activity as a % of cell-associated [177Lu] before incubation in non-radioactive medium.

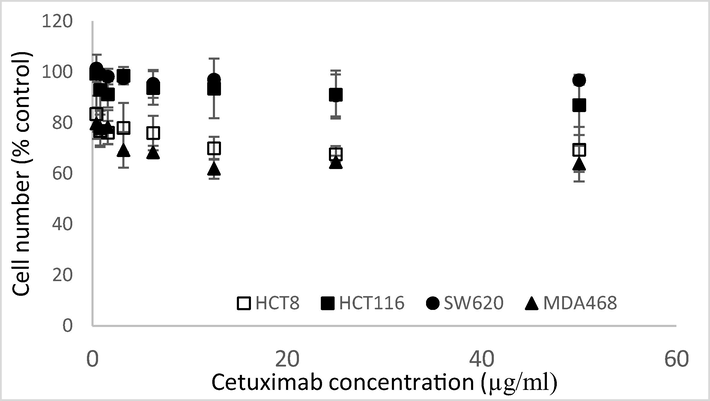

3.3 Cell sensitivity to Cetuximab

Fig. 3 shows the sensitivity of MDA-MB-468, HCT8, HCT116 and SW620 cells treated with increasing concentrations of Cetuximab for 72 h. MDA-MB-468 and HCT8 cells are the most sensitive cell lines and SW620 cells which do not express EGFR are insensitive to Cetuximab. HCT116 cells express EGFR but are resistant to EGFR-targeted treatments. Differences in cell number between the resistant/non-EGFR expressing cells and the sensitive ones is 20–30%. Cetuximab is growth inhibitory rather than cytotoxic so the differential effect on cell number in the resistant and responsive cells is not as great as would be expected with a drug such as docetaxel.

Sensitivity of HCT116 (black squares), HCT8 (white squares), MDA-MB-468 (black triangles) and SW620 (black circles) cells treated with 0–50 µg/ml of Cetuximab for 72 h determined using the MTT assay.(bars: SD from 3 determinations).

3.4 Inhibition of Colony formation by incubation of cells MDA-MB-468 cells with EGFR-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs.

Fig. 4 shows an activity-response curve for EGFR-expressing MDA-MB-468 cells incubated with 0.1–5 MBq of Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs for 4 h followed by incubation in non-radioactive medium for 11 days. A dose (2.8 MBq) that decreased colony formation to about 40% was chosen for subsequent experiments. Compared with the MTT assay colony formation was a more sensitive measure of the response to Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs.![Survival of MDA-MB-468 cells treated with 100KBq-5 MBq of EGFR-targeted-[177Lu]-AuNPs for 4 h then incubated for 11 days with non-radioactive medium. Cell survival was determined by counting the number of colonies > 50 cells (filled circles) or by the MTT assay (empty circles) after 11 days. Results were expressed relative to untreated cells.](/content/185/2021/33/7/img/10.1016_j.jksus.2021.101573-fig4.png)

Survival of MDA-MB-468 cells treated with 100KBq-5 MBq of EGFR-targeted-[177Lu]-AuNPs for 4 h then incubated for 11 days with non-radioactive medium. Cell survival was determined by counting the number of colonies > 50 cells (filled circles) or by the MTT assay (empty circles) after 11 days. Results were expressed relative to untreated cells.

3.5 Inhibition of proliferation of cancer cell lines by incubation with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs

Fig. 5 shows the effect of Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu] Lu-AuNPs labelled (2.8 MBq) treatment for 4 h followed by incubation for 6–11 days (depending on the growth rate of the cell line) in fresh medium. The formation of clones containing > 50 cells was decreased in each cell line. MDA-MB-468 cells exhibited the greatest growth inhibition with a colony count of 32% corresponding with its high EGFR expression determined previously (Cabello et al 2018). Exposure of cells to non-targeted [177Lu]-DOTA (2.8 MBq) for 4 h did not result in a significant growth inhibitory effect on any or the cell lines, demonstrating the importance of receptor-targeting of [177Lu] on therapeutic response.![Comparison of survival of EGFR-expressing cells HCT8, HCT116 and MDA-MB-468 cells incubated with EGFR-targeted 177Lu-AuNPs using the MTT assay (a) or colony formation assay (b) or incubated with 177Lu-DOTA using the colony formation assay (c) for 4 h, washed and incubated for 6 (HCT8), 8 (HCT116) or 11 (MDA-MB-468) days in non-radioactive media. Results expressed relative to MTT uptake (a) or to number of colonies (>50 cells) in non-treated plates (b and c). The mean values were statistically significant (p < 0.01) for each cell line treated with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs compared with untreated cells (a and b) but not cells treated with [177Lu]-DOTA (c).](/content/185/2021/33/7/img/10.1016_j.jksus.2021.101573-fig5.png)

Comparison of survival of EGFR-expressing cells HCT8, HCT116 and MDA-MB-468 cells incubated with EGFR-targeted 177Lu-AuNPs using the MTT assay (a) or colony formation assay (b) or incubated with 177Lu-DOTA using the colony formation assay (c) for 4 h, washed and incubated for 6 (HCT8), 8 (HCT116) or 11 (MDA-MB-468) days in non-radioactive media. Results expressed relative to MTT uptake (a) or to number of colonies (>50 cells) in non-treated plates (b and c). The mean values were statistically significant (p < 0.01) for each cell line treated with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs compared with untreated cells (a and b) but not cells treated with [177Lu]-DOTA (c).

3.6 Biodistribution and tumour dose-distribution

Fig. 6A shows the radioactive counts normalised by tissue weight (g) and injected dose in blood, tumour, liver, spleen, kidney, heart and lung. The liver and spleen show the highest uptake. Tumour uptake is higher than blood with a tumour to blood ratio of 3.02.![Biodistribution and distribution of activity in xenograft sections. Bio-distribution of [177Lu] in xenografted mice 4 h post-injection with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs (A). Storage phosphor imager autoradiographs of 50 µm sections from (B) tumour 1 (C) serial dilutions of [177Lu]-LuCl3 and (D) and standard curve of intensity (arbitrary units) vs applied activity (y = 0.0016x + 58, r = 0.97 p < 0.01 from serial dilutions). Each section was divided into 50 × 50 μm pixels and activity per area rather than concentration used to generate CoVs. For this reason data were segregated on the basis of tissue thickness.](/content/185/2021/33/7/img/10.1016_j.jksus.2021.101573-fig6.png)

Biodistribution and distribution of activity in xenograft sections. Bio-distribution of [177Lu] in xenografted mice 4 h post-injection with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs (A). Storage phosphor imager autoradiographs of 50 µm sections from (B) tumour 1 (C) serial dilutions of [177Lu]-LuCl3 and (D) and standard curve of intensity (arbitrary units) vs applied activity (y = 0.0016x + 58, r = 0.97 p < 0.01 from serial dilutions). Each section was divided into 50 × 50 μm pixels and activity per area rather than concentration used to generate CoVs. For this reason data were segregated on the basis of tissue thickness.

A typical autoradiograph from a section of one of the tumours is shown in Fig. 6B. The linearity of signal intensity on the storage phosphor screen is demonstrated by the strong correlation between the independently measured activity and intensity shown in 6C and 6D. Co-efficient of variation values (CoV) are shown Table 1 for each tissue section thickness. Mean CoV varied from 11.10% to 18.35%. No trend between section thickness and CoV was apparent.

CoV (%) for activity in each section from 3 tumours

Section thickness (um)

Tumour 1

Tumour 2

Tumour 3

10

17.93

9.33

10

15.76

17.69

10

20.47

10

14.89

10

15.25

20

12.90

13.39

11.43

20

14.64

25.00

10.79

20

15.25

16.67

50

9.42

10.83

9.48

50

12.15

11.92

12.86

50

10.55

16.16

12.07

50

11.10

19.07

10.70

50

29.41

18.87

10.67

50

11.07

10.58

13.72

50

12.55

8.70

13.31

50

14.67

23.12

10.13

50

13.36

9.51

8.22

50

14.00

17.42

50

16.35

50

18.21

50

13.88

50

19.56

Summary CoV data (mean ± SD)

Section thickness (µm)

Tumour 1

Tumour 2

Tumour 3

10

16.86 ± 2.09

13.50 ± 4.17

N/D

20

14.26 ± 0.99

18.35 ± 4.88

11.10 ± 0.32

50

13.82 ± 5.41

14.30 ± 4.83

13.32 ± 3.33

4 Discussion

The purpose of this work was to examine parameters that affect the cell killing efficacy of Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs including target affinity, which can be attenuated by conjugation with large compounds, duration of association with the target cell, inhomogeneities in intra-tumour dose-distribution and growth-inhibitory efficacy against Cetuximab-resistant tumour cells.

RIT has successfully been employed in the treatment of lymphomas resistant to CD20 receptor-targeting antibodies such as rituximab (Mondello et al., 2016). Resistance of EGFR- expressing tumours to the growth-inhibitory effects of Cetuximab is by several mechanisms including mutant Kras (De Roock et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2016) which results in activation of the MAPK pathway downstream of EGFR. In this study it was demonstrated that the EGFR receptor could be used for the delivery of a growth-inhibitory dose of beta-emitting radionuclides to Cetuximab-resistant Kras-mutant colorectal cancer cells.

The affinity of the Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs (KDis) for the EGFR was found to be 20 nM. Similar KDis have been noted previously for NP-antibody conjugates e.g. Debotton et al. (2010) binding of nanoparticle-anti-ferritin conjugates to ferritin using surface plasmon resonance KDis of 8.16 nM. Yin et al 2015 measured KDis of Herceptin-gold NPs by breast cancer cells and observed KDis of 13.33 and 8.06 by two different cell lines compared with KDis of 2 for non-conjugated Herceptin. The ‘hump’ in the initial part of the curve, a consistent finding from 5 separate experiments, would suggest that inclusion of a low concentration of non-complexed Cetuximab may increase the uptake of the complex. The targeting moiety Cetuximab was conjugated to the AuNP via a 5KDa PEG linker. Bloch et al. (2017) has shown that the use of shorter, more linear PEG linkers can increase affinity for receptor binding. Further Abstiens et al. (2019) have shown that shorter linkers increase cellular uptake of receptor targeted nanoparticle conjugates. However, Rudnick et al. (2011) examined tumour penetration using immunoglobulins (IgG) of different receptor affinities (0.09, 0.56, 7.3 and 23 nM) and showed that IgG with an affinity of 23 nM resulted in deeper tumour penetration than did the higher affinity IgG molecules suggesting that the affinity of the Cetuximab-[177Lu]-AuNP with a KDis of 20 nM may be optimal for RIT.

Ligand binding to the EGFR results in both rapid clathrin dependent endocytosis and the less efficient clathrin-independent endocytosis via caveolin (Le Roy and Wrana, 2005). After entering the cell, the EGFR-ligand complex can either be degraded or routed back to the plasma membrane and recycled (Yameen et al., 2014). In contrast with its natural ligand, epidermal growth factor, Cetuximab binding to the EGFR does not efficiently enhance its internalisation (Jones et al., 2020) which is predominantly by a clathrin independent mechanism involving caveolae coated pits (Dittmann et al., 2008). However, conjugation of Cetuximab with Au nanoparticles increases the rate of endocytosis by the EGFR (Bhattacharyya et al., 2020) and distribution between Golgi-apparatus and lysosomal compartments and the recycling compartment. Consistent with a two pathway mechanism for EGFR-complex recycling, the current study demonstrated that the rate of loss of cell activity after cells had been incubated for 4 h with Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs (Chiarelli et al., 2017; Satterlee et al., 2015; Frellsen et al., 2016) then in fresh medium was biphasic. Cell-irradiation also induces the redistribution of EGFR to the nucleus forming part of the cell’s survival response mechanism (Dittmann et al., 2008) which may also affect the rate of recycling/degradation of the Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNP complex.

Inhomogeneities in intra-tumour dose distribution is one of the major hurdles in RIT for therapeutic response optimisation (Ruan et al., 2000; Cicone et al., 2013). In the present study mean activity CoV of about 15% was observed in sections through xenografts. Possible strategies to improve dose homogeneity could be the use of two isotopes of different energies (de Jong et al., 2005; Rathke et al., 2019) or a combination of external beam radiotherapy and RIT (Ruan et al., 2000) for primary tumours.

Bio-distribution in mice bearing xenografts demonstrated that the greatest uptake of Cetuximab-targeted [177Lu]-AuNPs 4 h post injection was by the liver and spleen indicating that excretion was predominantly hepatobiliary. This is not surprising as the targeted nanoparticles were shown to have a diameter of 44 nm (Cabello et al 2018) which is far larger than the 5–6 nm renal filter threshold. In terms of clinical translation of complexes loaded with β-emitting radionuclides this is a drawback as the liver residence time for substances excreted via the hepatobiliary route is high compared with the much lower renal exposure for substances excreted via the kidney. To overcome this, we are developing ultra-small Au/Cu amalgams which are only 2 nm in diameter and will be decorated with short length bifunctional linkers (Cabello et al., 2019) that will be preferentially excreted through the kidney.

In summary this study has demonstrated that Cetuximab-[177Lu]-AuNPs possesses attractive features, including suitable target affinity, with potential to be used in the treatment of EGFR-overexpressing tumours including tumours that are resistant to antibody treatment. Translation will be dependent on the development of complexes with dimensions of<6 nm that undergo renal excretion.

Author contributions

Conception and design TS and RS; experimental TS, RS, MM, MvH, and GC; Analysis and writing all authors. All authors approved this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The work in this study was funded by The Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office (TCS 16/07). RS is a PhD student funded by a fellowship from the Saudi-Arabian government. AC, MvH, TADS are supported by NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ligand density and linker length are critical factors for multivalent nanoparticle−receptor interactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:1311-1320.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity and cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles: what we have learned so far? J. Nanopart. Res.. 2010;12(7):2313-2333.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoconjugation modulates the trafficking and mechanism of antibody induced receptor endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 2020;107:14541-14546.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of linker type and recognition peptide conjugation chemistry on tissue affinity and cytotoxicity of charged polyacrylamide. J. Control. Release. 2017;257:102-117.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicochemical tools: toward a detailed understanding of the architecture of targeted radiotherapy nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Biomater.. 2018;1(5):1639-1646.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cu@Au self-assembled nanoparticles as SERS-active substrates for (bio)molecular sensing. J. Alloys Compd.. 2019;791:184-192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoparticle biokinetics in mice and nonhuman primates. ACS Nano. 2017;11:9514-9524.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterisation of biologically compatible TiO2 nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2011;6 Article Number: 423

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantification of dose nonuniformities by voxel-based dosimetry in patients receiving Y-90-ibritumomab-tiuxetan cancer. Biother. Radiopharmaceut.. 2013;28:98-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- EGFR targeted therapies and radiation: optimizing efficacy by appropriate drug scheduling and patient selection. Pharmaceut. Therapeut.. 2015;154:67-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- A quantitative evaluation of the molecular binding affinity between a monoclonal antibody conjugated to a nanoparticle and an antigen by surface plasmon resonance. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Biopharmaceut.. 2010;74:148-156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combination radionuclide therapy using 177Lu- and 90Y-labeled somatostatin analogs. J. Nucl. Med.. 2005;46s:13S-17S.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol.. 2010;11:753-762.

- [Google Scholar]

- Radiation-induced caveolin-1 associated EGFR internalization is linked with nuclear EGFR transport and activation of DNA-PK. Mol. Cancer. 2008;7(1):69.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gold nanoparticle bioconjugates labelled with At-211 for targeted alpha therapy. RSC Adv.. 2017;7:41024-41032.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mouse positron emission tomography study of the biodistribution of gold nanoparticles with different surface coatings using embedded copper-64. ACS NANO. 2016;10:9887-9898.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacologic resistance in colorectal cancer: a review. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol.. 2016;8:57-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Broad RTK-targeted therapy overcomes molecular heterogeneity-driven resistance to cetuximab via vectored immunoprophylaxis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res.. 2016;382:32-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Targeting of eGfR by a combination of antibodies mediates unconventional eGfR trafficking and degradation. Sci. Rep.. 2020;10:633.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clathrin- and non-clathrin-mediated endocytic regulation of cell signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.. 2005;6:112-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- Targeting MET and EGFR crosstalk signaling in triple-negative breast cancers. Oncotarget. 2016;7:69903-69915.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lu-177-labeled antibodies for EGFR-targeted SPECT/CT imaging and radioimmunotherapy in a preclinical head and neck carcinoma model. Mol. Pharmaceut.. 2014;11(3):800-807.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface engineering of nanoparticles for targeted delivery to hepatocellular carcinoma. Small. 2018;14 pp. UNSP 1702037

- [Google Scholar]

- 90 Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan: a nearly forgotten opportunity. Oncotarget. 2016;7:7597-7609.

- [Google Scholar]

- A perspective on anti-EGFR therapies targeting triple-negative breast cancer. Am J Cancer Res.. 2016;6:1609-1623.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dosimetry Estimate and Initial Clinical Experience with 90Y-PSMA-617. J. Nucl. Med.. 2019;60:806-811.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breast cancer as a systemic disease: a view of metastasis. J. Intern. Med.. 2013;274:113-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of radiation therapy in the modern management of oligometastatic disease. J. Buon. 2017;22:831-837.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oligonucleotide-modified gold nanoparticles for intracellular gene regulation. Science. 2006;312:1027-1030.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimising the sequence of combination therapy with radiolabelled antibodies and fractionated external beam. J. Nucl. Med.. 2000;41:1905-1912.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of affinity and antigen internalization on the uptake and penetration of anti-HER2 antibodies in solid tumors. Cancer Res.. 2011;211:2250-2259.

- [Google Scholar]

- A radio-theranostic nanoparticle with high specific drug loading for cancer therapy and imaging. J. Control. Release. 2015;21:170-182.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of an imaging station for rapid colony counting in radiobiology studies. Appl. Rad. Isotopes.. 2019;152:106-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of F-18-fluorinatable dendrons and their application to cancer cell targeting. New J. Chem.. 2011;35:2496-2502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insight into nanoparticle cellular uptake and intracellular targeting. J. Contr. Release. 2014;190:485-499.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring binding kinetics of antibody-conjugated gold nanoparticles with intact cells. Small. 2015;11:3782-3788.

- [Google Scholar]