Translate this page into:

Effects of D-Limonene on aldose reductase and protein glycation in diabetic rats

⁎Corresponding author. shahidmahboob60@hotmail.com (Shahid Mahboob)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia can lead to other health complications. The pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus can affect numerous tissues in the eye structure and cataracts are one of the major causes of visual impairment in diabetes mellitus patients. In this study, we aim to investigate the ability of D-limonene to inhibit aldose reductase hypoglycemic activity in lens organ culture and its anti-glycating properties in STZ-induced cataracts of rats with diabetes. D-limonene repressed aldose reductase in-vitro with IC50 ranges of ∼13.9 ± 0.31 µg/mL in an uncompetitive manner. This compound also prevented hyperglycemic induced increases in aldose reductase activity, accumulation of sorbitol, altered crystalline proteins (α, β and γ), and opacification of the rat lens in ex-vivo lens organ culture. Supplementation of D-limonene in STZ-induced diabetic rats restored these changes and delayed the progression of cataracts. This study demonstrates that D-limonene is a pharmaceutically active component that inhibits rat-lens aldose reductase. Therefore, this study showed that D-limonene prevents advanced glycation end product formation contributing to the integrity of α-crystallin chaperone activity and delays cataract development. It has been concluded, D-limonene has a role in inhibiting aldose reductase activity and advanced glycation end products formation in vivo, and in delaying the development of diabetic cataracts. Further studies of D-limonene are needed to assess other complications in DM as they may provide additional evidence for establishing D-limonene as a potential pharmacological target therapy for diabetes mellitus complications.

Keywords

D-limonene

Aldose reductase

α-Crystalline

Advanced glycation

End products

Cataracts

1 Introduction

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), there are 17.6 million people who are blind from cataracts in the world (Khorsand et al., 2016; Pescosolido et al., 2016). Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder with a phenotype of chronic hyperglycemia, a risk factor for cataract development (Khan et al., 2014). Hyperglycemia, protein glycation and induced advanced glycation end products (AGE) plays an important role in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications (Singh et al., 2014). Aldose reductase (AR; ALR2; EC 1.1.1.21), is a key-enzyme in polyol pathways which catalyzes a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP)-dependent reduction of glucose to sorbitol. In diabetic tissues, it leads to an extreme accumulation of intracellular-reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS is engendered through AGE process formation and AGE-RAGE interactions leads to ROS production (Tang et al., 2012).

In 1912, Maillard, a French scientist, described modifications occurring in precise proteins prior to ascribing to sugars as the major cause of changing food color, known as the Maillard reaction. In 1955, glycated hemoglobin was discovered and was the first example of a molecule modified by exposure to blood sugar; this documented proof that the Maillard reaction occurs in the human body, and is now known as glycation (Fournet et al., 2018). Positivity in fructose formation leads to reactive dicarbonyl species in AGEs (Zhao et al., 2009). Maillard reactions are formed through the condensation of amino acids with carboxyl groups on reduced sugars which results in Schiff base formation and rearrangement to Amadori or Heyns products, followed by cross-linking of AGEs with characteristic fluorescence (Lund et al., 2017). Importantly, protein damage occurs during the initial process within lysine and N-terminal amino groups; further, these proteins are degenerated through crosslinking reactions of AGEs and dicarboxyl species in later reactions (McKay et al., 2019).

AGEs have been studied in the serum and lenses of diabetic subjects with cataracts (Chen et al., 2018). The function of the chaperone α-crystallin may be linked to the formation of diabetic cataracts and supporting studies have confirmed that reduced activity of the chaperone due to oxidative stress may be involved in cataract development (Nakazawa et al., 2016; Babizhayev, 2016). Identifying pharmacological inhibitors of aldose reductase and AGE formation could be effective in preventing diabetic cataracts (Saraswat et al., 2010). For example, terpenoids are the biggest photochemical group used in the medicinal preparation for numerous diseases due to their antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, antiallergic, antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory properties (Tewari et al., 2019; Thoppil et al., 2011).

D-limonene [1-methyl-1-4-(1-methylethyl) cyclohexane] is well established for its chemo-preventative activity in many cancers and other diseases. It is known as a natural monocyclic monoterpene and non-nutritive dietary component with a citrus odor applied in numerous indigenous medicines. The principal source of D-limonene as an essential oil is A. marmelos leaves, present in cherries, grapes, and citruses like lemon and orange (Murali et al., 2013). The hypoglycemic activity and antioxidant properties of D-limonene were verified in animal models. It was shown to modulate insulin secretion and lower lipid peroxidation and growth in STZ-induced diabetic rats (Sharma and Bansal, 2016). The in vitro studies showed the antiglycating role of D-limonene with bovine serum albumin (Joglekar et al., 2013). However, the role of D- in aldose reductase inhibition, which plays a major role in polyol pathway, and it’s in vitro effects on cataracts have not been documented. Thus, the current study inspects the role of D-limonene inhibition on aldose reductase ex vivo with lens organ culture and its antiglycating properties in cataracts in rats with STZ-induced diabetes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

D-limonene, lithium sulphate, NADPH, DL-glyceraldehyde, quercetin, β-mercaptoethanol, reduced-glutathione, TC-199 medium and sephacryl S-300HR were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (USA). DTT, insulin and Tris and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (UK). The animal protocol was designed to minimize pain or discomfort to the animals. The animals were acclimatized to laboratory conditions (23 °C, 12 h/12 h light/dark, 50% humidity, ad libitum access to food and water) for 2 wk prior to experimentation. Intragastric gavage administration was carried out with conscious animals, using straight gavage needles appropriate for the animal size (15–17 g body weight: 22 gauge, 1-inch length, 1.25 mm ball diameter). All animals were euthanized by following guidelines of American Veterinary Medical Association with commercial euthanasia solution (Sodium pentobarbital 390 mg + sodium phenytoin 50 mg/ml). The animals were euthanized by barbiturate overdose (intravenous injection, 150 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium) for tissue collection. The animals after sampling were placed in plastic bags and sealed. These sealed bags were shifted into another plastic bags and thrown into animal trash.

2.2 Inhibition studies of aldose reductase

Purification of aldose reductase was performed as previously described by Sankeshi et al. (2013). Briefly, the rat lens was incubated with 1 mL of the assay mixture (50 mM phosphate buffer, 0.4 M lithium sulphate, 5 mM 2-mercapto ethanol, 0.1 mM NADPH, and 10 mM DL-glyceraldehyde) at 37 °C for 5 min. A double beam spectrophotometer (Hitachi Spectrophotometer U-2910) was used to calculate the 340 nm absorbance of NADPH oxidation. The stock for D-limonene was prepared with water for the inhibition studies. 1–100 µM/mL concentrations of D-limonene were added for both the reaction mixture and AR activity assays.

2.3 Enzyme kinetic studies

200 µl of the same reaction mixture was prepared. The varied concentration ranges were 0.1–1.0 mM for both D-limonene and DL-glyceraldehyde compounds. Km and Vmax of AR was estimated through numerous concentrations of DL-glyceraldehyde as the substrate by Lineweaver-Burk double reciprocal plots.

2.4 Lens organ culture

Lens organ culture was performed as previously published by Reddy et al. (2000). Briefly, 60-day-old SD (Sprague Dawley) rat eye balls were dissected with the anterior approach. The lenses were incubated in 2 mL of TC-199 medium (ThermoFischer) at 37 °C at 5% CO2 and 50 mM glucose with or without D-limonene (13.49 µM/ml). Using the prepared medium with 30 mM fructose and 5.5 mM glucose, the lenses were incubated and treated with osmotic controls. Lenses were maintained in sorbitol for 24 h or 10 d for morphology studies. Completion of incubation was conducted by visual cues, and lenses were placed in transparent glass slides.

2.5 Sorbitol estimation in lens

Sustained lenses were placed in organ culture consisted of M199 with Earl's balanced salt solution, 3% fetal calf serum, and antibiotics (Penicillin 100 U ml − 1 and Streptomycin 0·1 mg ml−1) for 24 h, and were treated with 9 volumes of 0.8 M perchloric acid. Homogenates were centrifuged at 5000×g at 4 °C for 10 mins and the supernatant pH was adjusted to 3.5 with 0.5 M potassium carbonate. This protocol was initially published by Rao and Bhat (1989) using JASCO FP-750 spectrofluorimeter.

2.6 Animal experiment and induction of diabetes

Three month old male rats with an average weight of 220 ± 6 g were used in this study which was procured from the Departmental Animal House. All animal experiments were carried out as per the ethical guidelines for animal experimentation. Rats were fed the AIN-93 diet. Eight rats were involved in control group (Group-I) and received the STZ-injection (Streptozotocin-Induced) in 0.1 M citrate buffer. After 3-days, fasting glucose levels were monitored and abnormal glucose levels were categorized into 3 groups; Group-II (Gr. II) is considered a diabetic control group and was fed with a consistent AIN-93 diet. Group-III (Gr. III; n = 6) and Group-IV (Gr. IV; n = 6) were fed an AIN-93 diet with 0.013% or 0.13% of D-limonene, respectively. Every week, serum glucose levels were measured after overnight fasting for 8–10 h. Cataract progression was assessed as per the Suryanarayana et al. (2005) study. After 8 weeks, rats were used for in vivo studies.

2.7 Isolation of α-crystalline from rat lens

To perform isolation of α-crystalline, lenses were pooled from 5 to 6 rats and 10% of the tissue homogenate was isolated in TNE buffer (25 mM Tris-Hcl; 0.5 mM of EDTA and 100 mM of NaCl). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C and the pellet was used for further extraction. This technique was performed by adopting the earlier studies (Reddy et al., 2000).

2.8 Estimation of glycation of protein

Quantification of protein glycation in the rat lens was performed with boronate-affinity chromatography. One column was filled with aminophenylboric-acid and agarose beads and the other 5 columns were filled with “equilibrator buffer (0.25 M ammonium acetate, pH 8.5, 0.05 M MgCl2)”. Rat lens TSP (Trigonella foenum graecum seed powder) was applied to the column and the non-glycated protein fraction was eluted with equilibrator buffer while the glycated protein was bound to the phenyl boronate matrix (Kumar et al., 2009). A UV–Vis (Ultraviolet–visible) spectrophotometer instrument was used to perform this experiment.

2.9 Histopathological studies

Following completion of animal experiments, eye balls were dissected and fixed in 10% formaldehyde for 48 h. Eye balls were embedded in paraffin (60 °C) using L-blocks, sectioned at 5–7 µm thickness using a microtome and stained using H&E (Pilati et al., 2008).

2.10 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (Version 21.0; US). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for a minimum of three replicates. One-Way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using Post-Hoc tests.

3 Results

3.1 D-limonene inhibition activity by AR

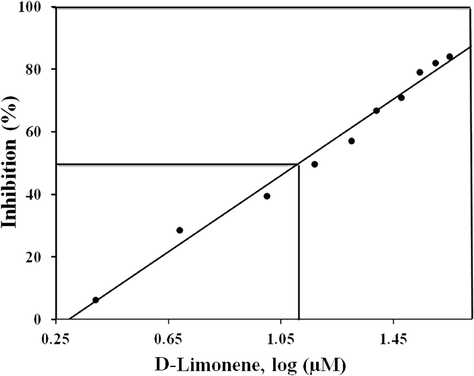

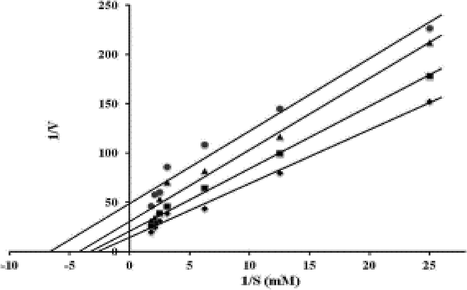

The inhibition activity of D-limonene toward AR (aldose reductase) was verified in the rat-lens. A comparison of the IC50 levels was undertaken with quercetin being used as a positive control of AR inhibition. The quercetin IC50 value was 8.947 ± 0.305 µM/mL. D-limonene inhibited AR in rat lens with an IC50 of 13.9 ± 0.31 µM/mL (Fig. 1). Kinetic parameters were determined using Km and Vmax to assess the mechanistic inhibition of AR via D-limonene. Various concentrations of D-limonene (Km and Vmax) appeared to lower the substrate DL-glyceraldehyde (Table 1). Additionally, D-limonene bound to the substrate–enzyme complex which does not compete as an inhibition substrate of AR in an uncompetitive manner (Fig. 2). Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Inhibition of AR by D-limonene: Representative inhibition curve of rat aldose reductase (AR) by D-limonene. AR activity in the absence of D-Limonene was considered as 100%. Data shown is an average of three independent experiments.

D-Limonene (µM)

Km(mM)

Vmax

0

0.25 ± 0.03

0.0703 ± 0.02

6.5

0.20 ± 0.02

0.0485 ± 0.01

13.9

0.166 ± 0.02

0.0326 ± 0.01

25.5

0.118 ± 0.01

0.020 ± 0.02

Kinetics of aldose reductase inhibition: Lineweaver–Burk plot of aldose reductase (AR) in the presence and absence of various concentrations of D-limonene. The concentration of D-limonene used in the assay system: 0 µM (♦), 6.5 µM (■), 13.9 µM (▲) and 25.5 µM (●).

3.2 Experimental prevention of D-limonene opacification in lens organ culture

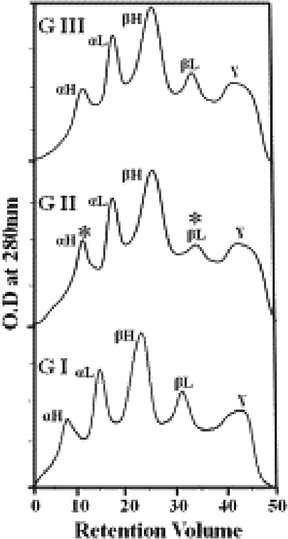

The potential role of D-limonene in preventing the accumulation of sorbitol and lens opacification was assessed in a long-term lens organ culture. The inhibition activity of D-limonene towards AR was high in the lenses incubated. In lenses with 50 mM glucose (Gr. II), AR activity was prohibited in hyperglycemic conditions and lower levels of sorbitol were detected when compared with controls in Gr. I and D-limonene supplementation in Gr. III (Table 2). Incubated lenses with 50 mM glucose for for 10 days have lost transparency and lenses supplemented with 13.9 µM/ml D-Limonene displayed a delayed on set and progression of lens opacification with 13.9 µM/mL. D-limonene treatment exhibited suspension of lens opacification. To investigate the mechanism of delayed progression of lens opacity of D-limonene, crystallin spreading profile was assessed. A decrease in both α- and βL-crystallin levels were documented in the lens incubated with 50 mM of glucose (Fig. 3). However, hyperglycemia induced alterations in the crystallin profile in lenses supplemented with D-limonene. Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *Statistically significant from Group I (analyzed by ANOVA; p ≤ 0.05).

Parameter

Group I

Group II

Group III

Aldose Reductase

31.0 ± 1.29

47.1 ± 2.13*

32.7 ± 2.96#

Sorbitol Level (nmoles/g lens)

32.0 ± 1.52

81.1 ± 1.57*

33.0 ± 2.75#

D-limonene prevented crystallin redistribution in lenses cultured in hyperglycemic conditions: Rat lenses were dissected from 2-month-old SD rats and incubated with 5.5 mM glucose and 30 mM fructose as a control (GI), 50 mM glucose (GII) and 50 mM glucose and 13.9 µg/mL of D-limonene (GIII).

3.3 D-limonene treatment in rats with STZ-induced cataracts

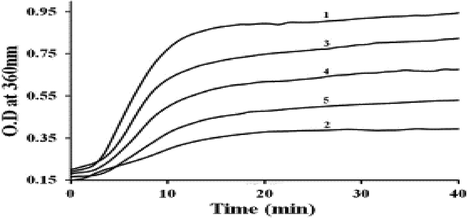

Rats involved in this study were fed a high calorie intake. Diabetic rats (Gr. II-IV) were compared with controls (Gr. I). The body weight of the diabetic controls was lower than controls (Gr. II 184 ± 6.91 g, Gr. I 325 ± 6.33 g) as well as rats supplemented with D-limonene (Gr. III 309 ± 10.1 g and Gr. IV 320 ± 3.17 g). Increased blood glucose levels were reduced with D-limonene treatment (Gr. III (95.86 ± 6.20); Gr. IV (89.80 ± 3.56) vs Gr. II (261.53 ± 53)). A decrease in AR activity in Gr. III and IV rats was shown in a dose-dependent manner following 8 weeks of supplementation (Table 3). Further, cataract progression was reduced in rats that were fed D-limonene. The chaperone activity of α-crystallin from untreated diabetic rats was lowered to 50% to prevent its activity in DTT-induced aggregation of insulin (Fig. 4). Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *Statistically significant from Group-I (analyzed by ANOVA; p ≤ 0.05). #Not statistically significant from Group-I (analyzed by ANOVA; p > 0.05).

Parameter

Control (Group I)

Diabetic Control (Group II)

Diabetic + 0.013% of D-Limonene (Group III)

Diabetic + 0.13% of D-Limonene (Group IV)

Aldose Reductase

35.01 ± 1.62

47.37 ± 1.38*

37.89 ± 1.03#

37.90 ± 0.91#

Sorbitol Level (nmoles/ g lens)

36.9 ± 1.29

76.2 ± 2.33*

45.4 ± 1.87*

44.5 ± 3.26*

Protein Carbonyls (nmoles/mg protein)

15.18 ± 0.58

27.52 ± 0.99*

19.05 ± 0.73*

18.87 ± 0.82*

Body Weight (grams)

325 ± 6.33

184 ± 6.91*

309 ± 10.1#

320 ± 3.17#

D-limonene preserved α-crystallin chaperone activity under diabetic conditions: α-crystallin was isolated from lenses of all four groups of experimental rats and its chaperone activity was assessed in terms of its ability to suppress DTT (dithiothreitol) induced aggregation by insulin. Insulin (0.40 mg/ml) was incubated in the absence (trace 1) or presence of α-crystallin from control rats (trace 2), diabetic rats (trace 3), diabetic rats treated with 0.013% of D-limonene (trace 4) and diabetic rats treated with 0.13% D-limonene (trace 5).

3.4 Anti-glycation effect of D-limonene with in vivo diabetic rats

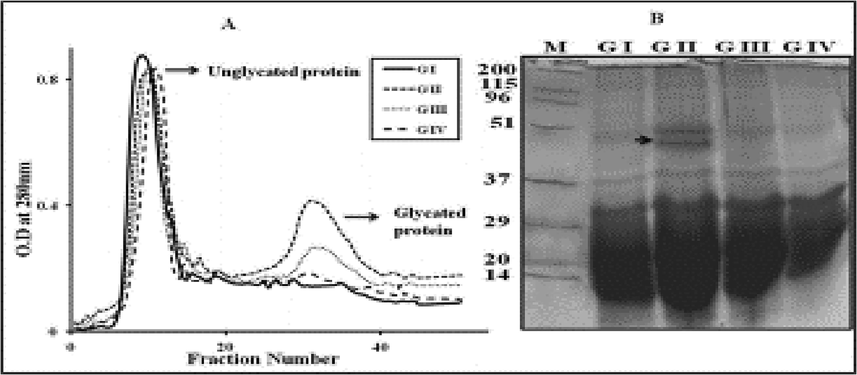

The volume of glycated protein in diabetic rats was lowered in dose-dependent manner shown in rats supplemented with D-limonene (Fig. 5A) as per the boronate-affinity chromatography. A significant decrease was observed in total and soluble proteins in the diabetic group compared to controls. D-limonene supplementation improved the protein levels, which have prevented the hyperglycemia-mediated high molecular weight cross-links in TSP (Fig. 5B).

Analysis of glycated proteins in STZ induced diabetic rat lens: The effect of D-limonene on the amount of glycated protein in rat lens TSP from different groups (GI to GIV) was analyzed by phenyl boronate affinity chromatography (A). SDS-PAGE analysis of lens TSP from Control (GI), diabetic control (GII), 0.013% D- Limonene treated (GIII) and 0.13% of D-Limonene treated diabetic rats (GIV); M-molecular weight markers. Arrowhead indicates high molecular weight aggregates (B).

3.5 Histological analysis

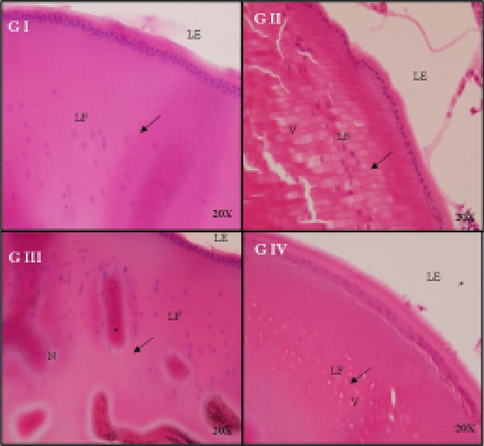

In control rats (Gr. I), the cellular architecture of the lenses was arranged in an order. However, in Gr. II of untreated diabetic cataract rats, cortical-fiber cell swelling and vacuoles in the cortical fiber region were observed. In rats receiving D-limonene (Gr. III), no vacuoles were detected. Finally, in Gr. IV, no remarkable changes were noted after treating with D-limonene (Fig. 6).

Histological examination of rat lens after treatment with D-limonene in a dose dependent manner: The cellular architecture of the lenses was orderly arranged. Control (GI), diabetic control (GII), 0.013% D- limonene treated diabetic rats (GIII) and 0.13% of D-limonene treated diabetic rats (GIV).

4 Discussion

Diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperglycemia can lead to other health complications. The pathogenesis of DM can affect numerous tissues in the eye structure and cataracts are one of the major causes of visual impairment in DM patients (Khan et al., 2019; Kiziltoprak et al., 2019). Several complications have been documented in the formation of AGE and AR-associated polyol pathways in DM. These pathways have been considered as major contributor towards oxidative-stress in tissues, mainly in the eye lens (Safi et al., 2014). Several AR and AGE inhibitors have been reported to prevent diabetic cataracts. However, AR or AGE inhibitors have many adverse side-effects and none are considered extremely safe (Younus and Anwar, 2016). Based on this issue, an attempt has been made to assess D-limonene and its inhibitory effect on AR activity and AGE formation in the diabetic cataract lens. In this present investigation, D-limonene showed considerable inhibitory activity towards AR. This study also documented the efficacy of D-limonene in ex-vivo lens culture under hyperglycemic conditions (Bai et al., 2016). Inhibition of AR activity by D-limonene was assessed by accumulation of sorbitol in the lens organ culture and the results confirmed the protective role in D-limonene in averting lens opacification in hyperglycemic conditions (Kim et al., 2015). Nutritious supplementation of D-limonene in STZ-induced diabetic rats inhibited AGE formation, improved α-crystalline chaperone activity and delayed cataract progression (Tewari et al., 2019). During cataractogenesis, proteins accumulate as insoluble aggregates resulting in lowered soluble-protein content. Although the soluble protein is significantly lowered in diabetic lenses, it was restored in lenses treated with D-limonene (Sakthivel et al., 2010). The distribution of the crystalline profile in soluble protein in lenses incubated with 50 mM glucose showed a decrease in βL-crystallin and increase in αH-crystalline which led to protein accretion in diabetic rat lenses, consistent with previous studies (Moghaddam et al., 2005; Sankeshi et al., 2013). Our observations revealed that D-limonene prevents the accumulation of high molecular weight isomers and protein carbonyls and improved the soluble protein levels. One of the major findings in this study was the inhibition of AR activity and destruction of sorbitol accumulation in lens organ culture with D-limonene. The process of altering the glycation, stability, cross-linking and aggregation of protein thus have a great influence on the pathogenesis of cataracts and retinopathies (Sankeshi et al., 2013).

A strong association has been documented between polyol pathways, AGE and chaperone activities in α-crystallins (Yan and Harding, 2006). The structure of chaperones and their activities are affected by glycation, which influences lens opacity (Yan and Harding, 2006). Glycation anticipation is mediated via loss of α-crystalline chaperone function and alteration structures in both in vitro and in vivo conditions which provision the anti-glycating effects of D-limonene have been shown (Moghaddam et al., 2005). Treatment with D-limonene lowers blood glucose levels and protein carbonyls and delays cataract progression; it is possible this is due to increased chaperone activity (α-crystalline) in the lenses of STZ-induced diabetes rats. Based on the investigations performed, we hypothesize that D-limonene plays a critical role in not only inhibiting AR and AGE formation but also in helping prevent α-crystalline chaperone activity. D-limonene thus merits further investigation in postponing and managing cataracts (Yan and Harding, 2006).

Our study investigated the ability of D-limonene to inhibit AR in the rat lens through in vivo, ex vivo and in vitro studies. This study highlights the efficacy of AR-inhibitors in preventing lens opacification in organ culture and AGE formation in STZ-induced hyperglycemia in rats. Isolation of α-crystalline from diabetic rat lenses treated with D-limonene exhibited a greater chaperone activity than the isolated fraction in untreated diabetic rats.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, D-limonene has a role in inhibiting AR-activity and AGE formation in vivo, and in delaying the development of diabetic cataracts. Further studies of D-limonene are needed to assess other complications in DM as they may provide additional evidence for establishing D-limonene as a potential pharmacological target therapy for DM complications.

6 Institutional animal care and use committee statement

All animal experiments conformed to the internationally accepted principles for the care and use of laboratory animals (licence No. 2013-15-2934-00784, The Animal Experiments Inspectorate, Denmark; protocol no. MI-17-0005, The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at MedImmune, Gaitherburg, MD, United States).

Acknowledgement

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the Research Supporting Project No. RSP-2019-93 the King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Generation of reactive oxygen species in the anterior eye segment. Synergistic codrugs of N-acetylcarnosine lubricant eye drops and mitochondria-targeted antioxidant act as a powerful therapeutic platform for the treatment of cataracts and primary open-angle glaucoma. BBA Clin.. 2016;6:49-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J., Zheng, Y., Wang, G., Liu, P.J.O.M., 2016. Protective effect of D-limonene against oxidative stress-induced cell damage in human lens epithelial cells via the p38 pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2016.

- Role of advanced glycation end products in mobility and considerations in possible dietary and nutritional intervention strategies. Nutr. Metab.. 2018;15(1):72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glycation damage: a possible hub for major pathophysiological disorders and aging. Aging Dis. 2018;9(5):880.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel mechanism for antiglycative action of limonene through stabilization of protein conformation. Mol. BioSyst.. 2013;9(10):2463-2472.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic confirmation of T2DM meta-analysis variants studied in gestational diabetes mellitus in an Indian population. Diabetes Metab. Syndr.. 2019;13(1):688-694.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism studies in Asian Indian pregnant women biochemically identifies gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone Syst.. 2014;15(4):566-571.

- [Google Scholar]

- Melatonin reduces cataract formation and aldose reductase activity in lenses of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Iran. J. Med. Sci.. 2016;41(4):305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Kim, C.-S., Sohn, E., Lee, Y.M., Jo, K., Kim, J.S.J.E.-B.C., et al., 2015. Litsea japonica extract inhibits aldose reductase activity and hyperglycemia-induced lenticular sorbitol accumulation in db/db mice. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2015.

- Delay of diabetic cataract in rats by the antiglycating potential of cumin through modulation of α-crystallin chaperone activity. J. Nutr. Biochem.. 2009;20(7):553-562.

- [Google Scholar]

- Control of Maillard reactions in foods: strategies and chemical mechanisms. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2017;65(23):4537-4552.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of collagen crosslinking in diabetes and keratoconus. Cells. 2019;8(10):1239.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Diabecon on sugar-induced lens opacity in organ culture: mechanism of action. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2005;97(2):397-403.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of D-limonene on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol.. 2013;112(3):175-181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of hesperetin on chaperone activity in selenite-induced cataract. Open Med.. 2016;11(1):183-189.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age-related changes in the kinetics of human lenses: prevention of the cataract. Int. J. Ophthalmol.. 2016;9(10):1506.

- [Google Scholar]

- A rapid method combining Golgi and Nissl staining to study neuronal morphology and cytoarchitecture. J. Histochem. Cytochem.. 2008;56(6):539-550.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of riboflavin deficiency on sorbitol pathway in rat lens. Nutr. Res.. 1989;9(10):1143-1149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temperature-dependent chaperone activity and structural properties of human αA-and αB-crystallins. J. Biol. Chem.. 2000;275(7):4565-4570.

- [Google Scholar]

- Safi, S.Z., Qvist, R., Kumar, S., Batumalaie, K., and Ismail, I.S.B.J.B.r.i., 2014. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic retinopathy, general preventive strategies, and novel therapeutic targets. BioMed Res. Int. 2014.

- Alterations in lenticular proteins during ageing and selenite-induced cataractogenesis in Wistar rats. Mol. Vision. 2010;16:445.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of aldose reductase by Aegle marmelos and its protective role in diabetic cataract. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2013;149(1):215-221.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiglycating potential of Zingiber officinalis and delay of diabetic cataract in rats. Mol. Vision. 2010;16:1525.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S., Bansal, N., 2016. D-Limonene ameliorates diabetic neuropathic pain in rats.

- Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Pharmacology. 2014;18(1):1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Curcumin and turmeric delay streptozotocin-induced diabetic cataract in rats. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci.. 2005;46(6):2092-2099.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aldose reductase, oxidative stress, and diabetic mellitus. Front. Pharmacol.. 2012;3:87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tewari, D., Samoilă, O., Gocan, D., Mocan, A., Moldovan, C., Devkota, H.P., et al., 2019. Medicinal plants and natural products used in cataract management. Front. Pharmacol. 10.

- Terpenoids as potential chemopreventive and therapeutic agents in liver cancer. World J. Hepatol.. 2011;3(9):228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H., Harding, J.J.J.M.V., 2006. Carnosine inhibits modifications and decreased molecular chaperone activity of lens alpha-crystallin induced by ribose and fructose 6-phosphate. Mol. Vis. 12, 205–214.

- Prevention of non-enzymatic glycosylation (glycation): implication in the treatment of diabetic complication. Int. J. Health Sci.. 2016;10(2):261.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advanced glycation end products inhibit glucose-stimulated insulin secretion through nitric oxide-dependent inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase and adenosine triphosphate synthesis. Endocrinology. 2009;150(6):2569-2576.

- [Google Scholar]