Translate this page into:

Effect of Mentha piperita L. stress at sub-inhibitory dose on some functional properties of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus hominis

⁎Corresponding authors. armankhan0301@gmail.com (Ameer Khusro), agastianloyolacollege@gmail.com (Paul Agastian)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The present context was aimed to assess the impact of Mentha piperita L. stress at sub-inhibitory concentration on some key functional traits of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus hominis strain MANF2. Initially, the antibacterial activity of M. piperita L. leaves was determined against strain MANF2 and estimated its minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and sub-MIC values using standard protocols. Results showed promising antibacterial activity of M. piperita L. against strain MANF2 with MIC and sub-MIC values of 25 and 12.5%, respectively. Further, strain MANF2 growing under mild stress of M. piperita L. i.e. stressed strain (SS) was tested for its prime functional properties using standard methodologies and compared with the control strain (CS). The SS culture showed increased growth with respect to the CS culture at regular interval of time. A significant (P < 0.05) decrement in the viabilities of SS culture were estimated as compared to CS culture from pH 2.0 to 5.0. The survival potentialities of SS culture with respect to CS culture were decreased too due to the supplementation of bile salt. The SS culture showed increased hydrophobicity towards chloroform (64.3 ± 1.2%), toluene (73.3 ± 1.1%), and ethyl acetate (69.2 ± 2.2%) as compared to CS culture. Likewise, the auto-aggregation traits of SS culture (74.1 ± 1.3%) were increased with respect to CS culture (68.1 ± 1.5%). The autolysis abilities of SS culture were increased too with respect to CS culture up to 24 h. In addition, antibiotics such as penicillin G and chloramphenicol showed increased activities against SS culture, while, gentamicin showed slight reduction in its activity against SS culture. In conclusion, functional characteristics of strain MANF2 can be enhanced by supplementing mild doses of M. piperita L. without altering the antibiotic susceptible characteristics of particular strain.

Keywords

Antibiotics

Functional properties

Mentha piperita L.

Staphylococcus hominis

Stress

1 Introduction

The ability of probiotic bacteria to resist sub-lethal stresses is achieved mainly by inducing diversified adaptive mechanisms. The exposure of such unfavourable conditions results into the up- and down-regulation of certain genes, thereby triggering transcriptional alterations in the cells and synthesizing new proteins (Khusro, 2016). As a matter of fact, the main purpose of adaptive mechanisms to the stress response is to protect cells against lethal factors and to repair damaged organelles. Surprisingly, the sub-lethal stress is known to alter the metabolic activities of the bacterium by repressing and inducing specific groups of protein (Khusro et al., 2014a).

The potentiality to resist acidic pH and bile salt, exhibiting cell surface properties, showing susceptibility to antibiotics, and producing bioactive components are the pivotal characteristics of probiotic bacteria (Aarti et al., 2018). It is essential to maintain the functional characteristics of probiotic bacteria after exposure to disparate stress conditions. Probiotic bacteria are often exposed to heat, cold, oxidative, osmotic, acid, and bile while determining their promising probiotic and technological characteristics (Amund, 2016). Bacteria adapt varied strategies to these stresses response viz. protein folding, synthesis of oxygen-stress protective proteins, synthesis of cold induced proteins, extrusion of protein by F0-F1-ATPase, bile efflux pumps, variations in energetic metabolism etc. (Amund, 2016). Previously, Paradeshi et al. (2018) investigated the impact of copper ions stress on functional traits of Lactobacillus sp. In another study, Haddaji et al. (2015) determined the cell adhesion characteristics of Lactobacillus sp. under heat shock treatment.

Despite the gastro-intestinal, metal ions, and physico-chemical stresses, the influence of antimicrobials, particularly medicinal plants at sub-lethal doses on the functional characteristics of probiotic bacteria is very limited, probably unavailable in fermented food associated coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. Hence, it certainly emphasizes the necessity to investigate medicinal plant’s stress effect on functional properties of bacteria. In fact, it is essential to maintain the biological properties of bacteria after its exposure to stress environment for its colossal applications in various industries.

In view of this, the present study was investigated to determine the influence of Mentha piperita L. stress at sub-lethal concentration on growth and some key functional attributes of Staphylococcus hominis. In order to provide new insight regarding the adaptive strategies, hypothetical pathways for some of the functional properties studied under stress were also discussed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Medicinal plant of interest

Mentha piperita L. (Family – Lamiaceae), commonly called as ‘peppermint’ was purchased freshly from the local market of Nungambakkam, Chennai, India and stored at 4 °C. Initially, the fresh leaves of M. piperita L. were sterilized using 95% (v/v) ethanol and washed with sterilized distilled water. Leaves were homogenized using grinder, filtered through muslin cloth, and then centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and filter sterilized using 0.2 µm syringe filter which was considered as 100% (Khusro and Sankari, 2015).

2.2 Bacterium of interest

Staphlococcus hominis strain MANF2 isolated from fermented food in our previous study (Khusro et al., 2018) was cultured in de Man Rogose Sharpe (MRS) broth (HiMedia laboratories, Mumbai, India) medium at 30 °C and considered as control strain (CS).

2.3 Antibacterial activity of M.piperita L.

The antibacterial activity of M. piperita L. was determined against strain MANF2 using disc diffusion method (Bauer et al., 1966). In brief, strain MANF2 was cultured into sterilized MRS broth aseptically, incubated at 30 °C for 24 h, and swabbed on freshly prepared MRS agar medium. Sterile discs were soaked with M. piperita L. and placed aseptically over previously prepared MRS agar plate (seeded with the test bacterium). Plate was incubated at 30 °C for 48 h and observed for the zone of inhibition.

2.4 Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and sub-MIC

The MIC and sub-MIC values of M. piperita L. were determined against strain MANF2 using microdilution assay as per the methodology of Khusro and Sankari (2015). The lowest concentration of M. piperita L. inhibiting the growth of strain MANF2 was determined as MIC value. Half of the value of MIC was calculated as sub-MIC of M. piperita L.

2.5 Preparation of stressed strain (SS)

M. piperita L. (1.5% v/v) was supplemented into log phase (8 h) of strain MANF2 culture (data not shown) and incubated at 30 °C to provide mild stress to the bacteria. Bacteria growing in the presence of M. piperita were considered as SS.

2.6 Growth profile of bacteria

The CS and SS cultures were prepared by growing into 50 mL of MRS broth. Cultures were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. One millilitre of culture was withdrawn from each flask aseptically every 6 h and the growth pattern was analyzed by reading absorbance at 600 nm using UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Khusro et al., 2014b).

2.7 Morphological analysis

The variations in the cellular morphology were observed as per the method of Khusro et al. (2014a). The CS and SS cultures were grown up to 48 h and then centrifuged at 8000 g for 15 min. Pellets were washed using sterilized distilled water. The suspension was centrifuged again at 8000 g for 15 min and pellets were re-suspended in 1 mL of sterile distilled water. An aliquot of each bacterial suspension was spread on clean glass slide and Gram staining was performed to observe the variations in the cellular morphology of CS and SS cultures. The stained cells were observed under light microscope at 100X magnification.

2.8 Acid tolerance

The acid resistance characteristics of CS and SS cultures were assessed as per the method of Ramos et al. (2013). Viabilities of cells were calculated as log cfu/mL.

2.9 Bile salt resistance

The resistivity of CS and SS cultures towards bile salt was evaluated according to the method of Kumar et al. (2011) and viabilities of cells were calculated after 24 h.

2.10 Cell surface hydrophobicity

The adherence traits of CS and SS cultures to hydrocarbons were analyzed as per the methods of Mishra and Prasad (2005). Cultures were grown in MRS broth and centrifuged. Pellets were mixed with phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.0) and the absorbance was read at 600 nm (A). The cell suspension was mixed with hydrocarbons (chloroform, toluene, and ethyl acetate) in the ratio of 3:1 and vortexed for some time, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 1 h. The reduction in absorbance was recorded at 600 nm (A0). The hydrophobicity percentage (%) was estimated as per following formula:

2.11 Auto-aggregation

Cell auto-aggregation traits of CS and SS cultures were estimated as per the method of Juárez Tomás et al. (2005). A significant reduction in absorbance represents the auto-aggregation characteristic and it was calculated as per the equation mentioned below:

2.12 Cell autolysis

Autolysis traits of CS and SS cells were determined as per the method of Mora et al. (2003). The autolysis was estimated as the reduction (%) in absorbance at 630 nm up to 24 h.

2.13 Antibiotics susceptibility pattern

The sensivity of CS and SS cultures to conventional antibiotics (streptomycin, penicillin G, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, gentamicin, nalidixic acid, and rifampicin), obtained from HiMedia laboratories, Mumbai, India was assessed using disc diffusion technique as per the method of Aarti et al. (2017). The growth inhibition was calculated in terms of millimetre (mm) after 48 h.

2.14 Statistical analyses

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Analysis of variance was implemented for validation and values with P ≤ 0.05 were reported significant.

3 Results

3.1 Antibacterial activity of M.piperita L. and sub-MIC determination

M. piperita L. exhibited pronounced antibacterial activity against strain MANF2 with 20.3 ± 0.03 mm of zone of inhibition (Figure not shown). The MIC value of M. piperita L. against strain MANF2 was calculated as 25%. Thus, the sub-MIC value of M. piperita L. against strain MANF2 was estimated as 12.5% (Figure not shown).

3.2 Growth profile of bacteria

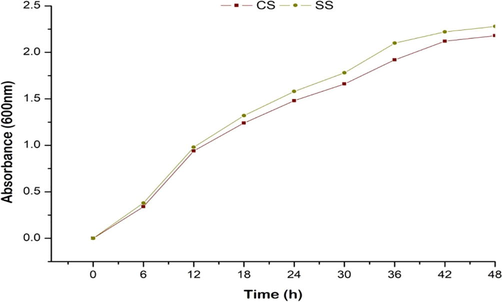

The growth of CS culture varied with respect to SS culture. The bacteria growing under mild stress of M. piperita showed increased growth with respect to the CS culture at regular interval of time (Fig. 1).

Growth response of CS and SS cultures.

3.3 Morphological analysis

The variations in cellular morphology of strain MANF2 under mild stress of M. piperita was observed under light microscope. Light microscopic observation of SS cells confirmed the heterogeneous nature of the cellular suspension as compared to CS cells. A drastic alteration in the morphology of SS cells was reported when observed at 100X magnification. Cells were separated apart with distortion in the shape from coccus to more or less round in shape (Figure not shown).

3.4 Acid tolerance

Table 1 shows the acid tolerance abilities of CS and SS cultures at distinct pH values. A significant (P < 0.05) reduction in the viabilities of SS culture were estimated as compared to CS from pH 2.0 to 5.0. However, the viabilities of SS culture were slightly increased as compared to CS culture at pH 6.5. Values represent mean ± SD of experiments carried out in triplicate (n = 3). a,bMeans with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

pH

Time period

CS cultures (log cfu/mL)

SS cultures (log cfu/mL)

2.0

0

5.65 ± 0.02a

5.6 ± 0.03a

1

5.6 ± 0.02a

5.51 ± 0.02b

2

5.46 ± 0.02a

5.32 ± 0.02b

3

5.25 ± 0.01a

5.1 ± 0.01b

3.0

0

5.92 ± 0.03a

5.88 ± 0.03b

1

5.87 ± 0.06a

5.8 ± 0.06b

2

5.77 ± 0.03a

5.65 ± 0.03b

3

5.57 ± 0.01a

5.45 ± 0.01b

4.0

0

6.0 ± 0.01a

5.98 ± 0.01b

1

5.96 ± 0.01a

5.84 ± 0.01b

2

5.90 ± 0.02a

5.80 ± 0.02b

3

5.85 ± 0.02a

5.65 ± 0.02b

5.0

0

6.04 ± 0.03a

6.0 ± 0.03a

1

6.0 ± 0.01a

5.86 ± 0.01b

2

5.94 ± 0.05a

5.82 ± 0.05b

3

5.93 ± 0.01a

5.73 ± 0.01b

6.5

0

6.21 ± 0.05a

6.23 ± 0.05b

1

6.21 ± 0.03a

6.25 ± 0.03b

2

6.22 ± 0.01a

6.28 ± 0.01b

3

6.2 ± 0.01a

6.3 ± 0.01b

3.5 Bile salt resistance

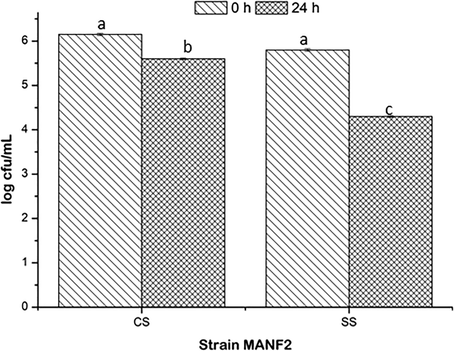

The survival potentialities of SS culture with respect to CS culture were decreased due to the addition of bile salt. Viabilities of CS and SS cultures were estimated as 5.6 ± 0.02 and 4.3 ± 0.02 log cfu/mL, respectively at 24 h of incubation (Fig. 2).

Bile salt tolerance of CS and SS cultures. Values are represented as mean ± SD of experiments carried out in triplicate (n = 3). abValues with different letters are significantly (P < 0.05) different.

3.6 Cell surface hydrophobicity and auto-aggregation

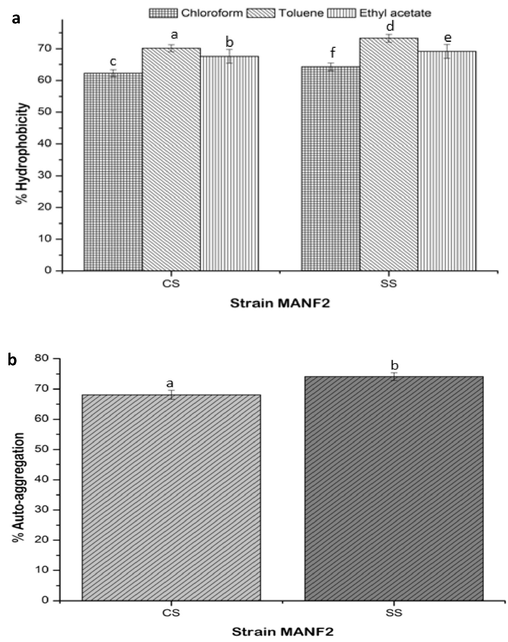

Under mild stress of M. piperita, the bacteria showed significant increment in the hydrophobicity to chloroform (64.3 ± 1.2%), toluene (73.3 ± 1.1%), and ethyl acetate (69.2 ± 2.2%) as compared to CS culture (Fig. 3a). Likewise, auto-aggregation of SS culture (74.1 ± 1.3%) was increased with respect to CS culture (68.1 ± 1.5%) (Fig. 3b).

(a) Cell surface hydrophobicity and (b) auto-aggregation traits of CS and SS cultures. Values are represented as mean ± SD of experiments carried out in triplicate (n = 3). abcdefValues with different letters are significantly (P < 0.05) different.

3.7 Cell autolysis

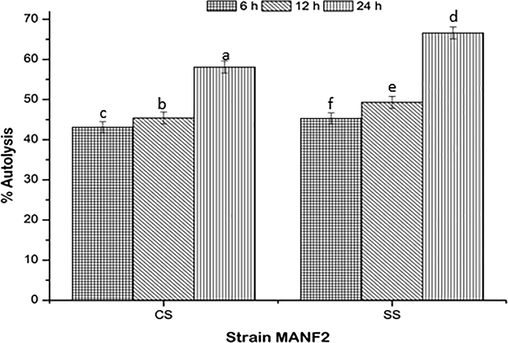

The autolysis abilities of SS culture were increased with respect to CS culture. The SS culture showed autolysis percentage of 45.3 ± 1.4, 49.3 ± 1.5, and 66.6 ± 1.5% at 6, 12, and 24 h of incubation, respectively (Fig. 4).

Autolysis abilities of CS and SS cultures. Values are represented as mean ± SD of experiments carried out in triplicate (n = 3). abcdefValues with different letters are significantly (P < 0.05) different.

3.8 Antibiotics susceptibility assay

Fig. 5 shows the susceptibility patterns of CS and SS cultures to conventional antibiotics. The CS culture showed sensitivity towards the tested antibiotics in the order of penicillin G (32.3 ± 0.3 mm) > gentamicin (31.3 ± 0.4 mm) > rifampicin (30.3 ± 0.5 mm) > kanamycin (22.3 ± 0.6 mm) > chloramphenicol (21.3 ± 0.5 mm) > streptomycin (13.3 ± 0.4 mm). The strain was resistant to nalidixic acid. Likewise, SS culture showed more or less similar pattern of sensitivity towards rifampicin (30.6 ± 0.5 mm), kanamycin (22.2 ± 0.5 mm), and streptomycin (13.6 ± 0.4 mm). Penicillin G and chloramphenicol showed increased activities against SS culture with zone of inhibition of 34.4 ± 0.4 and 22.6 ± 0.6 mm, respectively. On the other hand, gentamicin showed slight reduction in its activity against SS culture with diameter of zone of inhibition of 28.3 ± 0.5 mm. The SS culture was observed resistant to nalidixic acid too, as similar to CS culture.![Antibiotic sensitivity test of CS and SS cultures. Values are represented as mean ± SD of experiments carried out in triplicate (n = 3). *Values differed significantly (P < 0.05) with #values. [Note: A – Kanamycin, B – Penicillin G, C – Gentamicin, D – Streptomycin, E – Chloramphenicol, F – Rifampicin, and G – Nalidixic acid].](/content/185/2020/32/4/img/10.1016_j.jksus.2020.03.005-fig5.png)

Antibiotic sensitivity test of CS and SS cultures. Values are represented as mean ± SD of experiments carried out in triplicate (n = 3). *Values differed significantly (P < 0.05) with #values. [Note: A – Kanamycin, B – Penicillin G, C – Gentamicin, D – Streptomycin, E – Chloramphenicol, F – Rifampicin, and G – Nalidixic acid].

4 Discussion

Stress is known to alter the growth and metabolism of bacteria. In this context, strain MANF2 growing under mild stress of M. piperita L. i.e. SS culture showed increased growth with respect to CS culture at different time periods. Similarly, Khusro et al. (2014b) exhibited increased growth of Bacillus sp. under mild stress of metal ions as compared to the control strain. The increased growth of SS culture indicated that strain MANF2 received stimulation after sensing M. piperita L. stress and the process within them began working excess for neutralizing the stress. Accumulation of active constituents of M. piperita L. in the bacterial cells and in their cell wall may be one of the reasons for the bacterial rapid growth compared to control because bacteria divide more in order to release the toxicity (Khusro et al., 2020). In general, M. piperita L. has been used as antibacterial agents since ancient period. Phytocomponents such as flavonoids, phenols, and terpenoids present in the leaves of M. piperita L. are mainly responsible for antibacterial activities (Singh et al., 2015). In another study, Paradeshi et al. (2018) demonstrated reduction in the growth of Lactobacillus sp. under the mild stress of copper ions.

Variations in the morphology of microorganisms due to stress are an indicator of their adaptation. The alterations in bacterial morphology as a response to adverse situations have been demonstrated in prior reports (Ritz et al., 2001; Khusro et al., 2014a). In the present context, the cellular morphology of strain MANF2 under mild stress of M. piperita L. was altered with significant reduction in size and distortion of their shape. The microscopic image provided strong evidence that M. piperita L. at sub-lethal concentration is stressful for the strain MANF2, thereby changing their shape and size from cocci to more or less round shape as an adaptive strategy. In general, morphological changes are induced when the bacterial cells are incubated with sub-inhibitory concentrations of antimicrobials (Khusro et al., 2014a).

The ability to resist acidic conditions is the pivotal quality of probiotics. In this study, CS and SS cultures showed survival potentialities at low pH. However, the ability to resist acidic pH was comparatively lower for SS culture with respect to CS culture. In a like manner, Paradeshi et al. (2018) estimated reduced acidic pH resistance ability of probiotic bacteria grown under copper ions stress.

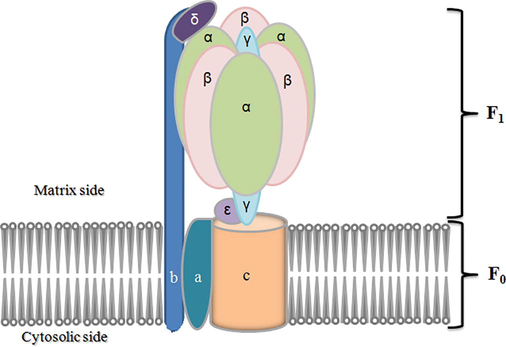

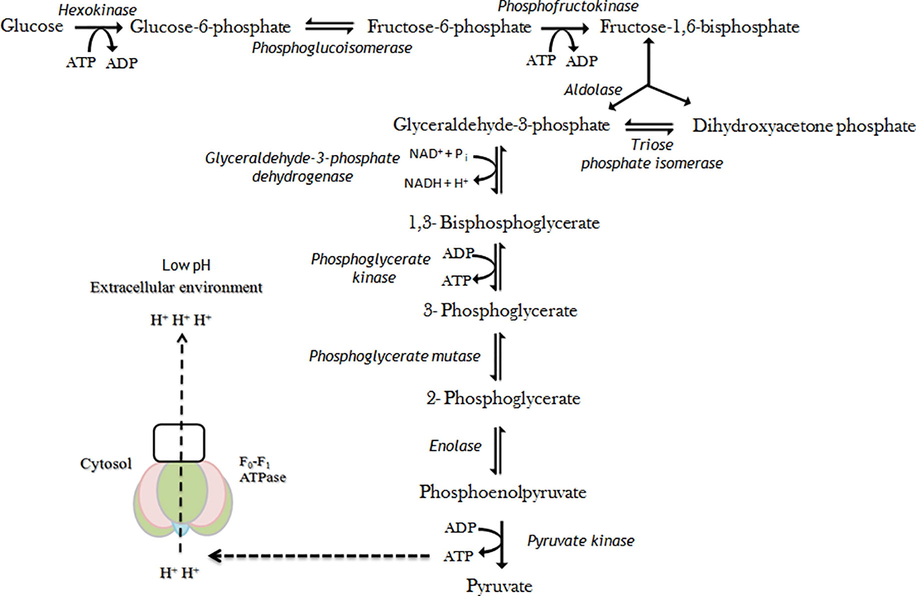

The low pH resistivity trait of gram positive bacteria indicates constant gradient between extracellular and cytoplasmic pH. Metabolic activities of cells are inhibited when the internal pH reaches a threshold value, and thus, bacteria lose the viability (Kashket, 1987). Gram positive bacteria tolerate the acidic environment by stimulating F0F1-ATPase mechanism (Cotter and Hill, 2003). The F0F1-ATPase is a multiple-subunit enzyme that contains a catalytic portion (F1) incorporating α, β, γ, δ, and ε subunits for ATP hydrolysis and an integral membrane portion (F0) including a, b, and c subunits (Fig. 6). It acts as a membranous channel for the translocation of proteins (Sebald et al., 1982). The F0F1-ATPase generates proton motive force by proton expulsion process in organisms devoid of a respiratory chain. As a result, F0F1-ATPase increases the intracellular pH (Fig. 7). Low pH induces F0F1-ATPase, and regulation occurs at the transcriptional state (Fortier et al., 2003).

F0F1-ATPase consisting of a catalytic portion (F1) incorporating α, β, γ, δ, and ε subunits for ATP hydrolysis and an integral membrane portion (F0) including a, b, and c subunits.

Acid tolerance pathway mechanism of CS culture. The F0F1-ATPase generates proton motive force by proton expulsion process in organisms devoid of a respiratory chain. The F0F1-ATPase increases the intracellular pH at low extracellular pH. The F0F1-ATPase is induced at low pH, and regulation appears to occur at the transcriptional level. The F0F1-ATPase requires ATP for expulsion of protons from the cell, thereby maintaining pH homeostasis and cell viability. ATP is obtained from the glycolysis process through step wise enzymatic mechanism.

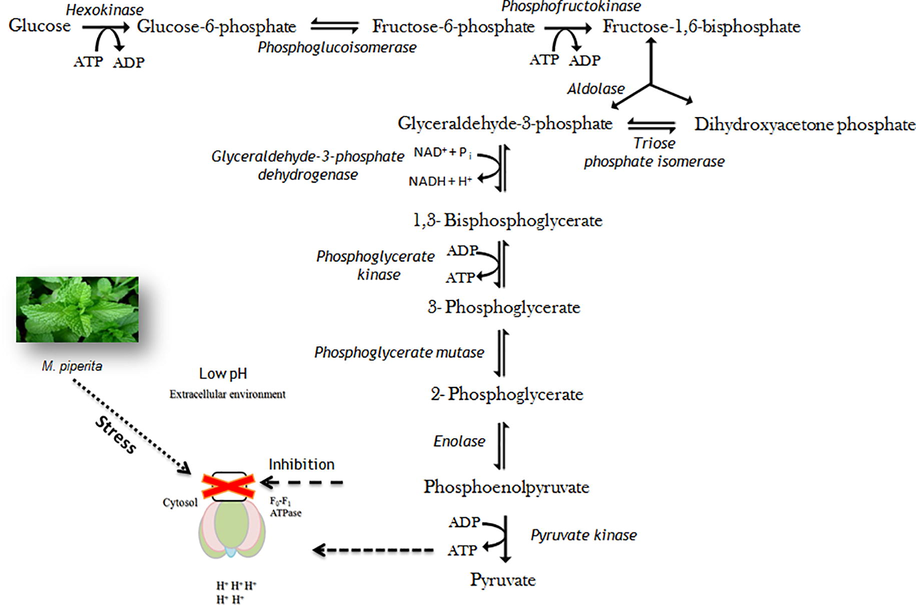

In this study, we suggested the plausible inhibition of F0F1-ATPase due to M. piperita L. stress and thus subsequent reduction in the viability of strain MANF2. In general, F0F1-ATPase was up-regulated due to low acidic pH in CS culture. On the other hand, the supplementation of M. piperita L. inhibited the F0F1-ATPase by covalent modification, as a result, ATPase did not pump out protons, thereby preventing proton translocation and causing reduced viability. Based on the outcomes of this study, it was hypothesized that mild stress of M. piperita L. caused conformational variations in the F0F1-ATPase, leading to alterations in its metabolic activities, particularly disturbing the acid expulsion potentiality and thus, reducing resistivity to acidic pHs. The ATP is essential for F0F1-ATPase to remove protons from cells, which maintains pH homeostasis and cells viabilities. The ATP is accumulated due to glycolysis. This hypothetical mechanism links glycolysis, ATP synthesis, and inhibition of F0F1-ATPase activity due to M. piperita L. stress (Fig. 8).

Hypothetical pathway for reduced viability of SS culture. The supplementation of M. piperita L. inhibited the F0F1-ATPase by covalent modification, as a result, ATPase did not pump out protons, thereby preventing proton translocation and causing reduced viability. The mild stress of M. piperita L. caused conformational variations in the F0F1-ATPase, leading to alterations in its metabolic activities, particularly disturbing the acid expulsion potentiality and thus, reducing resistivity to acidic pHs. The F0F1-ATPase requires ATP for expulsion of protons from the cell, thereby maintaining pH homeostasis and cell viability. The ATP is accumulated due to glycolysis. This hypothetical mechanism established a link between glycolysis, ATP synthesis, and inhibition of F0F1-ATPase activity due to M. piperita L. stress.

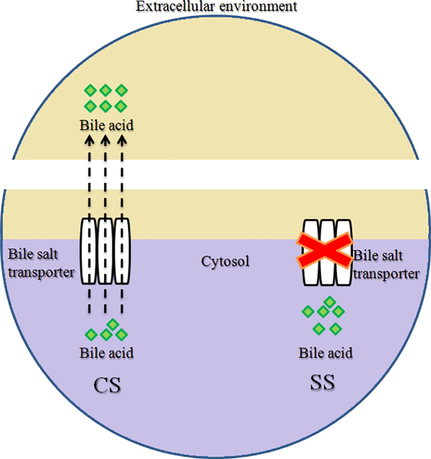

The tolerance to bile salt is another pivotal functional property of probiotic bacteria. In this study, the viabilities of SS culture reduced significantly as compared to CS culture due to bile salt supplementation, thereby indicating reduction in the bile salt resistance potentiality of stressed bacteria with respect to non-stressed bacteria. Likewise, Paradeshi et al. (2018) determined reduced resistivity traits of metal ions-stressed probiotics toward bile salt. The hypothetical mechanism behind the reduced viability of SS cultures in bile salt availability is shown in Fig. 9. In a nutshell, the sub-lethal dose of M. piperita L. in the cytoplasm might have affected the expression of varied membrane proteins that may inhibit bile transporters representing ATP-binding cassette.

Hypothetical pathway mechanism revealing the viability of CS and SS cultures in the presence of bile salt. The sub-lethal dose of M. piperita L. in the cytoplasm might have affected the expression of varied membrane proteins that may inhibit bile transporter mechanism of strain MANF2, representing ATP-binding cassette.

Stress alters the hydrophobicity traits of bacteria. Under mild stress of M. piperita L., bacteria showed significant increment in the hydrophobicity levels towards toluene. This might be due to the weak attractions of stressed cells with toluene and comparatively weak repulsion with ethyl acetate and chloroform. Observations confirmed that changes in the hydrophobicity trait occurred because of adaptative response of bacteria to M. piperita L. stress. In previous study, Haddaji et al. (2015) estimated increased hydrophobicity trait of probiotic bacteria under heat shock stress.

Auto-aggregation is a crucial factor to evaluate bacterial adhesion characteristic to the intestinal cell line. In this study, the auto-aggregation properties of SS culture were increased as compared to CS culture. Results favour the study of Paradeshi et al. (2018) who revealed enhanced auto-aggregation characteristic of probiotic bacteria under copper stress. Likewise, the autolysis abilities of SS culture were increased with respect to CS culture. There is no study reported earlier assessing the role of any kind of stress on the autolysis nature of probiotic bacteria. Hence, comparative analysis of our results with previous finding is not discussed here. However, Khusro et al. (2014c) suggested that bacteria under stress adapt themselves by activating autolysis mechanisms.

The susceptibility of strain(s) to wide ranges of antibiotics is essential in pharmaceutics. The lack of transferable antibiotic resistance genes is a pivotal characteristics of probiotics. In the present context, similar to CS culture, the SS culture was observed susceptible to most of the antibiotics tested, thereby exhibiting its putative probiotic attributes. On the other hand, SS culture was resistant to nalidixic acid, similar to CS culture. Findings indicated that despite the growth under sub-lethal concentration of M. piperita L., the susceptibility nature of bacteria to tested antibiotics was found to be unaltered. This might be due to the reason that the mild stress of M. piperita L. did not induce antibiotic resistance genes in SS culture. Similar findings were demonstrated by Paradeshi et al. (2018) too.

5 Conclusions

Strain MANF2 growing under mild stress of M. piperita L. showed increased growth with respect to the CS culture at varied period of time. The cellular morphology of strain MANF2 was distorted under mild stress of M. piperita L., as observed under light microscope. The viabilities of SS culture were reduced as compared to CS culture at low pHs. In like manner, the survival abilities of SS culture with respect to CS culture were decreased too due to the supplementation of bile salt. On the other hand, SS culture showed significant increment in the hydrophobicity, auto-aggregation, and autolysis properties as compared to CS culture. The SS culture showed more or less similar pattern of sensitivity towards rifampicin, kanamycin, and streptomycin. Penicillin G and chloramphenicol showed increased activities against SS culture. On the other hand, gentamicin showed slight reduction in its activity against SS culture.

Acknowledgement

Authors acknowledge Maulana Azad National Fellowship (F1-17.1/2015-16/MANF-2015-17-BIH-60730), University Grants Commission, Delhi, India for the support. The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP-2019/144), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- In vitro investigation on probiotic, anti-Candida, and antibiofilm properties of Lactobacillus pentosus strain LAP1. Arch. Oral Biol.. 2018;89:99-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro studies on probiotic and antioxidant properties of Lactobacillus brevis strain LAP2 isolated from Hentak, a fermented fish product of North-east India. LWT Food Sci. Technol.. 2017;86:438-446.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the relationship between exposure to technological and gastrointestinal stress and probiotic functional properties of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. Can. J. Microbiol.. 2016;62:715-725.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol.. 1966;45:493-496.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surviving the acid test: responses of grampositive bacteria to low pH. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.. 2003;67:429-453.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fortier, L.C., Tourdot-Maréchal, R., Divie‘s, C., Lee, B.H., Guzzo, J., 2003. Induction of Oenococcus oeni H-ATPase activity and mRNA transcription under acidic conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 222, 165–169.

- Change in cell surface properties of Lactobacillus casei under heat shock treatment. FEMS Microbiol. Lett.. 2015;362

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of culture conditions on the growth and auto-aggregation ability of vaginal Lactobacillus johnsonii CRL 1294. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2005;99:1383-1391.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioenergetics of lactic acid bacteria: cytoplasmic pH and osmotolerance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.. 1987;46:233-244.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic potential of anti-tubercular peptides: A million dollar question. EC Microbiol.. 2016;4:697-698.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-pathogenic and technological traits of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from Koozh, a fermented food product of South India. Food Biotechnol.. 2018;32:286-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adaptational changes in cellular morphology of Bacillus subtilis strain KPA in response to certain antimicrobials. Int. J. ChemTech Res.. 2014;6:2815-2823.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study on antagonistic activity of a novel bacterial isolate under mild stress condition of certain antimicrobial agents. Europ. J. Exp. Biol.. 2014;4:26-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple heavy metals response and antibiotic sensitivity pattern of Bacillus subtilis strain KPA. J. Chem. Pharm. Res.. 2014;6:532-538.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and estimation of total protein in Bacillus subtilis strain KPA under mild stress condition of certain antimicrobials. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res.. 2015;8:86-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production and purification of anti-tubercular and anticancer protein from Staphylococcus hominis under mild stress condition of Mentha piperita L. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.. 2020;182:113136

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lactobacillus plantarum (VR1) isolated from an Ayurvedic medicine (Kutajarista) ameliorates in vitro cellular damage caused by Aeromonas veronii. BMC Microbiol.. 2011;11:152.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Application of in vitro methods for selection of Lactobacillus casei strains as potential probiotics. Int. J. Food Microbiol.. 2005;103:109-115.

- [Google Scholar]

- Autolytic activity and pediocin induced lysis in Pediococcus acidilactici and Pediococcus pentosaceus strains. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2003;94:561-570.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of copper on probiotic properties of Lactobacillus helveticus CD6. Int. J. Dairy Technol.. 2018;71:204-212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strain-specific probiotics properties of Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus brevis isolates from Brazilian food products. Food Microbiol.. 2013;36:22-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological and physiological characterization of Listeria monocytogenes subjected to high hydrostatic pressure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2001;67:2240-2247.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure and genetics of the H+-conducting F0 portion of the ATP synthase. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.. 1982;402:28-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Mentha piperita L. Arab. J. Chem.. 2015;8:322-328.

- [Google Scholar]