Translate this page into:

Effect of humic acid enriched cotton waste on growth, nutritional and chemical composition of oyster mushrooms (Pluerotus ostreatus and Lentinus sajor-caju)

⁎Corresponding author. anam.zahidrana@gmail.com (Anam Zahid)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Humic acid (HA) is natural product obtained by plant decomposition. It improves systematic resistance in plants and the shelf life of food products. Oyster mushrooms occupy important place in human food due to their palatability and nutritional enrichment. Little is known about the impacts of HA on mushrooms yield. Therefore, a trial was conducted to study the role of HA improving growth, nutritional and chemical composition of two oyster mushroom strains (Pleurotus ostreatus, Lentinus sajor-caju). Pure cotton waste amalgamated with five levels of HA, i.e., 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 mM/L was used as growth media. The responses of oyster mushroom to HA were recorded in various traits i.e. time to spawn initiation, time to mycelium growth initiation, time to maturity of flushes, time to initiation of pinheads, yield, biological efficiency (BE), minerals (N, P, K, and ascorbic acid, Zn, Cu, Mg, Mn, Fe, Na and Ca), sugars (total sugars, reducing and non-reducing sugars), proximate, total soluble solids (TSS), acidity, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The HA amalgation notably improved the growth, nutritional and chemical composition of oyster mushroom; however, strains differences were non-significant (>0.05) to various level of HA on dry weight basis TSS ranged from 6 to 6.8 °Brix, total sugar was 5.8–11.9%, reducing sugar was 2.6–3%, non-reducing sugar was 9.2–9.6%, ascorbic acid was 35.9–43 mg/100 g, carbohydrates were 68–74%, crude protein was 62–69%, crude fiber was 22–37%, fat contents were 2.5–17%, ash content was 9–11%. These results suggest that HA is an innovative substrate for valuable and high-quality production of the oyster mushroom.

Keywords

Oyster mushroom

Humic acid

Crude protein

Biological efficiency

Reducing sugar

- BE

biological efficiency

- HA

humic acid

- TSS

total soluble solids

- PDA

potato dextrose agar

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Mushroom is a macro-fungus with epigeous or hypogenous fruiting structure, visible with naked eye (Chang, 1991). Oyster mushroom (class: Basidiomycetes) has edible flushy fruiting body and is consumed worldwide. White oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus) and Phoenix oyster (Lentinus sajor-caju) are the two most important types of oyster mushroom (Ayodele and Akpaja, 2007).

The name oyster originated from oyster shell like appearance of pileus i.e. the cap of fruiting body (Wood and Smith, 1988). Oyster mushroom has wide fan like fruiting body, which has white to creamy lamella or gills. Pluerotus species are widely distributed in wild. Moreover, different agro-industrial waste is used as growth media for domestic and commercial production of oyster mushroom (Jonathan and Adeoyo, 2011). Production and quality of mushroom is directly influenced by type of growth media. The most common type of substrate used are waste cotton, paper waste, sugar mills waste, cereals straws and crop leftovers (wheat, rice, millet and maize etc) (Jonathan and Esho, 2010; Fasidi et al., 2008). Cotton waste is most suitable substrate for oyster mushrooms (Sardar et al., 2017). Non-conventional substrate is the most important factor of mushroom’s production (Muhammad et al., 2019). Oyster mushrooms grow well at temperature range of 22–28 °C and > 85% humidity (Onyango et al., 2011).

Oyster mushroom is a low calory healthy food rich in protein, vitamins and minerals (Kalmıs et al., 2008). Oyster mushrooms regulate the immune system, lower blood sugar & lipid levels and have antiseptic, anticarcinogenic, anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and anti-inflammatory properties (Gunde-Cimerman, 1999; Zervakis, 2005).

HA is gaining popularity as low-cost organic fertilizer in agriculture. Previous studies showed that humic substances increase the root, shoot and leaf growth; also boost the germination of different crops (Piccolo et al., 1993). The HA plays important role in uptake of minerals (S, P, K and N) (Arslan and Pehlivan, 2008). Moreover, the HA has positive morphological and physiological effects on growth of higher plants (Trevisan et al., 2010) like pepper (Karakurt et al., 2009) and tomato (Adani et al., 1998). The HA plays imporatnt role in biosynthesis of various proteins and enzymes (Nardi et al., 2007). In addition, HA is also beneficial to increase yield and quality of oyster mushrooms (Prakash et al., 2010).

However, role of humic acid in growth and quality of oyster mushroom is not well studied. Therefore, an experiment was conducted to study the effect of HA amalgamated with cotton waste substrate on growth, yield and quality of oyster mushroom.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research material

Two commercial strains of oyster mushroom that is white tree oyster (V1P1) and Phoenix oyster (V2P3) were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (PanReac AppliChem, Spain) media at Medicinal and Mushroom lab, Institute of Horticultural Sciences, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad.

2.2 Spawn preparation

The spawn was prepared by mixing boiled wheat grains with animal waste manure 2% CaCO3 and 2% CaSO4 as described by (Khan et al., 2019). Firstly, wheat grains were boiled until softness and then mixed with other constituents. The substrate was autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min followed by overnight cooling and inoculation with mycelium on PDA. At the 17th day of inoculation, the spawn was shaken for even distribution of wheat grains and re-incubated for eight days until grains were fully impregnated with mycelium.

2.3 Preparation of substrate and bag filling

Cotton waste was used as a substrate. It was soaked in water and pH was maintained by adding two percent lime. After that substrate was wrapped with polythene and placed in open for 5 days to allow fermentation. Excessive water from substrate, evaporated by spread on floor. The substrate was amalgamated with different level of humic acid solutions of 0 (Control), 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 mM/L designated as T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, and T6 respectively. The trial was conducted in triplicated CRD design. Each replication had 12 bags (each bag has 800 g of substrate), one for each combination of variety and treatment (Rodriguez Estrada and Royse, 2007).

2.4 Agronomic features

In the presence of light, the bags were incubated at 24 ± 2 °C and 80% R.H. for mycelia growth. After the completion of colonization, bags were shifted in cropping room at the temperature of 18 ± 2 °C with 80–90% R.H. in order to increase the fructification. Different agronomic features were measured such as (i) time to mycelium growth initiation, (ii) time to completion of 1st, 2nd and 3rd flushes, (iii) time to pinhead formation, (iv) total yield and (v) BE.

2.5 Determination of sugar contents

Reducing, non-reducing and total sugars along with total soluble solids (Brix) were estimated in mushroom extract as described by (Hortwitz, 1960).

2.6 Nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and ascorbic acid contents

Fruiting bodies of oyster mushrooms were oven dried at 60 °C for 48 h and grinded to pass through 1 mm sieve. One gram of grinded sample was digested in HNO3 (0.6 mol/L). Finally, this prepared solution was used for the determination potassium by flame photometer, phosphorus by spectrophotometer and nitrogen by kjeldhal’s method (Mapya, 1998). Ascorbic acid was measured quantitively with titration method using 2, 6- dichloro-indo-phenol dye Tillmans reagent (Tillman’s method).

2.7 Estimation of minerals contents

One gram of fruiting body powder was burnt for 15 h at 560 °C in a muffle furnace (Atila et al., 2017). After that, ash was digested with HNO3 (0.6 mol/L). Mn, Cu, Zn and Fe measured by atomic absorption spectrometer (230ATS), while Ca, Mg and Na measured by flame photometer (Mapya, 1998).

2.8 Estimation of proximate

Protein, fat, ash and total carbohydrates were estimated as described by AOAC (1995). The crude fiber was measured with the procedure that was recommended by Ranganna (1986).

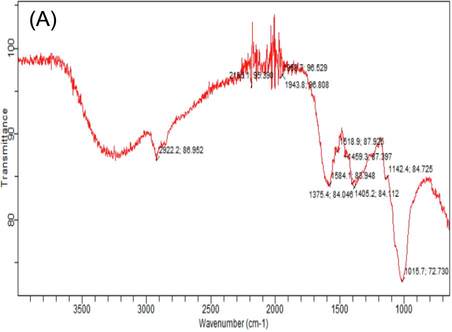

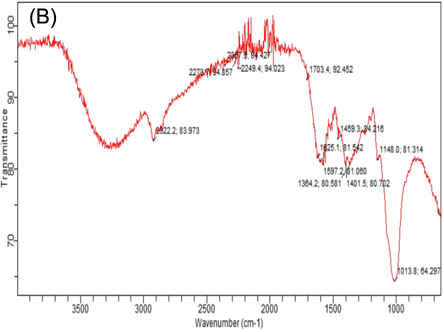

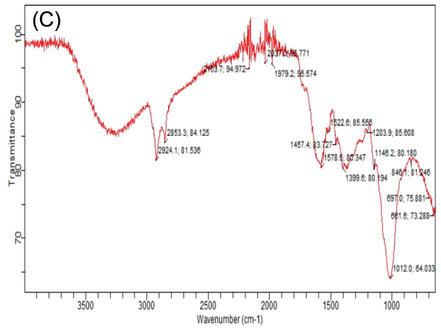

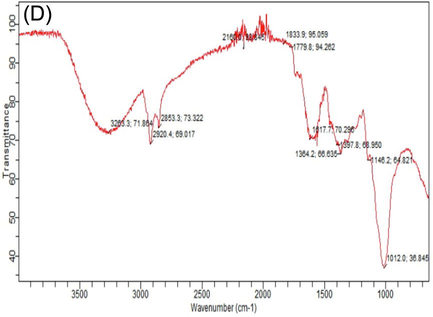

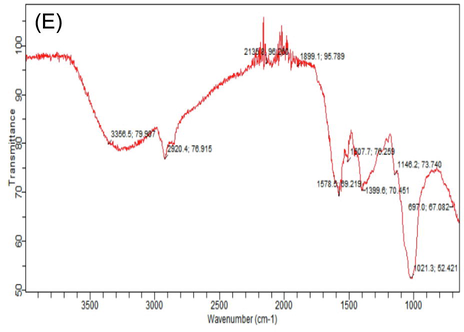

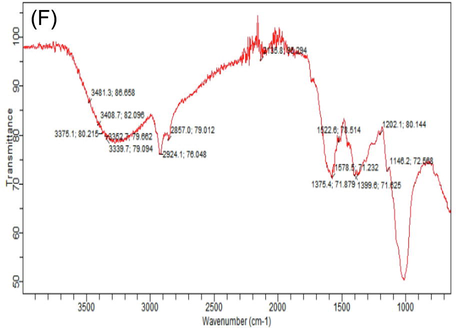

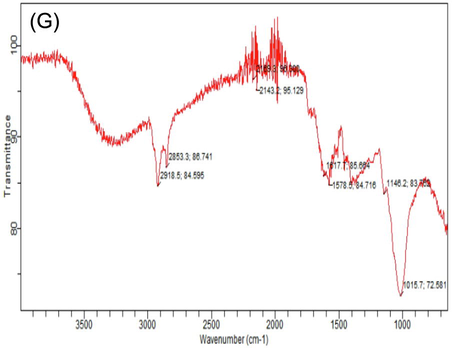

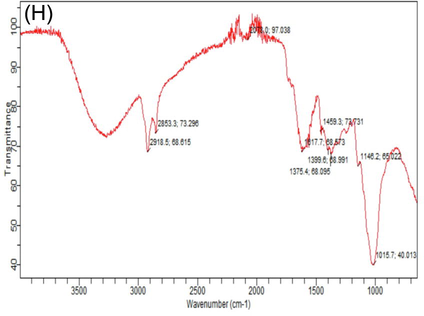

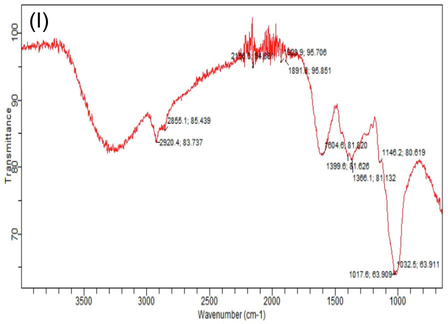

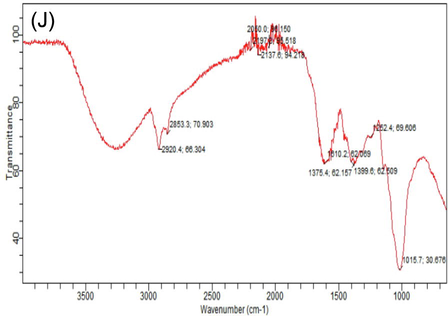

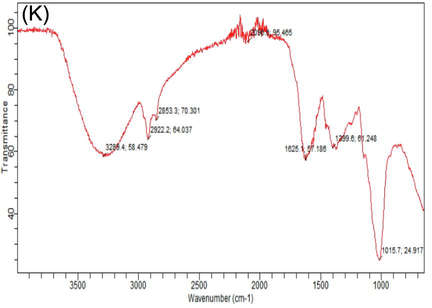

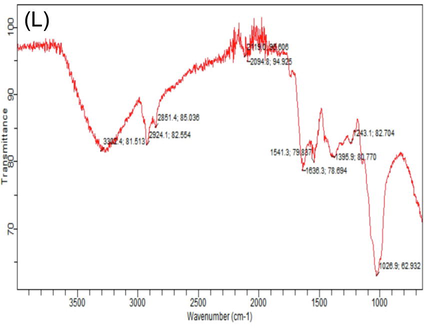

2.9 Molecular structure

Structural changes at molecular level in both strains of oyster mushroom were studied through Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Agilent 680, Department of Chemistry, University of Engineering and Technology Lahore, Faisalabad, Pakistan). 1 mg of grounded sample was mixed in 100 mg KBr and compressed to form tablets. Spectra were recorded from 650 to 4000 per cm (Muhammad et al., 2019).

2.10 Statistical analysis

Experiment was conducted in completely randomized design (CRD). Data was subjected to analysis of variance (one way). The data were analyzed with the software of Statistix 8.1. Significance of differences among treatments means were tested using LSD test α = 0.05 (Steel and Torrie, 1980).

3 Results

3.1 Time to spawn initiation, 100% mycelium growth and pinhead formation

Analysis of variance revealed no significant differences in time to spawn initiation among both varieties of oyster mushrooms subjected to various levels of humic acid. However significant differences were observed in time taken for full mycelium growth and pinhead formation in response to different levels of humic acid. Out of six humic acid levels, least time for complete mycelium growth was given by T6 (39.1 days) whereas max days (48.7, 48.0 days) were observed in T1 and T2 for white oyster mushroom. Same trend was observed for mycelial growth in Phoenix oyster mushroom i.e maximum days for mycelial growth was observed in T1 (52.5 days) and minimum days were observed in T6 (39.1 days). Moreover, raw cotton substrate complemented with humic acid exhibited fast mycelium growth. It is depicted that different levels of humic acid and strains of oyster mushroom significantly affected the time to pinhead formation. Minimum time (53.0 days) was shown by T6 and maximum time (65.0 days) in T1 by variety white oyster. However, in phoenix oyster, treatments T6 (57.0 days) and T1 (67.0 days) significantly affected the days taken to pinhead formation as compare with others (Table1). Mean value (n = 3) in the same column with the same following letter do not significantly differ (p < 0.05). (T1 = Control, T2 = 2 mM/L humic acid, T3 = 4 mM/L humic acid, T4 = 6 mM/L humic acid, T5 = 8 mM/L humic acid, T6 = 10 mM/L); V1 (P1) = White oyster mushroom; V2 (P3) = Phoenix oyster mushroom.

Treatments

Time to spawn initiation (days)

Time to mycelium growth initiation (days)

Time to Initiation of pinhead’s (days)

Time to maturity of flushes (days)

Yield

Biological efficiency (BE)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)100%

V2(P3)100%

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)1st flush

V2(P3)1st flush

V1(P1) 2nd flush

V2(P3)2nd flush

V1(P1)3rdflush

V2(P3)3rd flush

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

T1

2.0 ± 0.1

1.4 ± 0.5

48.7 ± 3.5a

52.5 ± 1.7a

65.0 ± 2a

67.0 ± 2a

90.3 ± 1a

87.0 ± 2a

100.3 ± 5a

97.0 ± 2a

110.3 ± 3a

107.0 ± 2.5a

184.0 ± 5d

245.3 ± 5e

45.1 ± 2f

61.7 ± 2d

T2

2.0 ± 1.0

1.6 ± 1.1

48.0 ± 2a

49.7 ± 2.2a

63.3 ± 1a

62.0 ± 2b

84.0 ± 2b

83.3 ± 2ab

94.0 ± 2b

95.3 ± 2ab

104.0 ± 3.5bc

105.3 ± 1.1ab

248.0 ± 7c

338.3 ± 8d

62.2 ± 2e

84.4 ± 1c

T3

1.3 ± 0.5

2.0 ± 1.0

46.7 ± 2ab

45.5 ± 2b

64.0 ± 3a

61.3 ± 1b

83.6 ± 2b

80.3 ± 2bc

93.6 ± 2b

91.3 ± 1.1bc

106.6 ± 3ab

101.3 ± 1.5 cd

301.0 ± 12b

438.3 ± 8b

67.2 ± 2d

86.3 ± 1c

T4

1.3 ± 0.5

2.0 ± 1.0

44.0 ± 3.5ab

43.0 ± 2bc

63.6 ± 3a

62.6 ± 2b

82.0 ± 2bc

85.0 ± 2a

94.0 ± 2.5b

93.0 ± 2bc

101.0 ± 3 cd

99.0 ± 1dc

259.6 ± 9c

340.0 ± 5d

74.3 ± 2c

85.4 ± 3c

T5

1.0 ± 0

2.3 ± 1.5

43.2 ± 2bc

40.2 ± 1.5 cd

62.0 ± 1a

60.0 ± 2bc

83.3 ± 2b

83.6 ± 2ab

92.3 ± 1.1b

94.6 ± 3ab

102.3 ± 2bcd

104.6 ± 2bc

320.0 ± 26b

405.3 ± 6c

109.2 ± 3b

105.5 ± 3b

T6

1.0 ± 0.1

1.0 ± 0

39.1 ± 2c

39.1 ± 2d

53.0 ± 1b

57.0 ± 2c

79.6 ± 1c

78.0 ± 1c

91.6 ± 2.5b

90.0 ± 2c

99.6 ± 1.5d

98.0 ± 2e

547.6 ± 15a

580.0 ± 5a

137.6 ± 2a

146.3 ± 1a

3.2 Time to maturity of flushes and yield (g)

The different concentrations of humic acid exhibited significant effects on days taken to harvest ready flushes in both strains of oyster mushroom. Less time was taken by treatment T6 and maximum was taken by T1. In both strains of oyster mushroom treatment T6, T5, and T3 showed min days for the maturity of 1st and 2nd flushes as compared to control T1. Moreover, minimum time taken for the completion of 3rd flush by the treatments T6 and T4 than control T1. The yield of mushroom obtained from cotton waste supplemented with humic acid was significantly higher in treatments T6, T5, and T3 in both varieties as compared to control T1 (Table 1).

3.3 Reducing, non-reducing and total sugars and total soluble solids (TSS)

Humic acid significantly increased total soluble solids (⁰Brix). Among different treatments of HA, max total soluble solids were noticed in treatment T6, following T5 and minimum TSS was recorded in T1. The highest value of TSS was regarded for T6 as compared to T1 in both varieties. Maximum TSS was observed in white oyster as compared to phoenix oyster. Cotton waste enriched with HA showed the significant increase in the total sugar contents. HA significantly boosted the reducing and non-reducing sugars. Maximum reducing and non-reducing sugars were seen in treatment T6 and min was observed in T1 in both varieties (Table 2). Mean value (n = 3) in the same column with the same following letter do not significantly differ (p < 0.05). (T1 = Control, T2 = 2 mM/L humic acid, T3 = 4 mM/L humic acid, T4 = 6 mM/L humic acid, T5 = 8 mM/L humic acid, T6 = 10 mM/L); V1(P1) = White oyster mushroom; V2(P3) = Phoenix oyster mushroom.

Treatment s

Total soluble solids (⁰Brix)

Total sugars (%)

Reducing sugars (%)

Non-reducing sugars (%)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

T1

4.2 ± 0.2c

4.5 ± 0.9b

5.8 ± 0.3e

6.8 ± 0.3e

0.4 ± 0.02d

1.1 ± 0.1c

5.5 ± 0.2d

5.8 ± 0.2e

T2

4.7 ± 0.2c

5.1 ± 1.2b

9.1 ± 0.3d

8.6 ± 0.3d

1.2 ± 0.2c

1.4 ± 0.3c

7.9 ± 0.3c

7.1 ± 0.2d

T3

5.4 ± 0.4b

5.4 ± 1.2b

9.8 ± 0.3c

10.1 ± 1.3c

1.6 ± 0.3c

2.4 ± 0.3b

8.2 ± 0.2c

7.6 ± 0.3c

T4

5.5 ± 0.4b

5.8 ± 1.3a

11.1 ± 0.2b

11.1 ± 0.1b

2.1 ± 0.2b

3.1 ± 0.1a

8.8 ± 0.2b

7.8 ± 0.1c

T5

6.2 ± 0.4a

6.2 ± 1.1b

11.4 ± 0.3b

11.8 ± 0.2a

2.4 ± 1.3ab

3.1 ± 0.1a

9.1 ± 0.3b

8.5 ± 0.2b

T6

6.4 ± 0.4a

6.3 ± 1b

12.1 ± 0.3a

12.1 ± 0.3a

2.6 ± 0.2a

3.2 ± 0.3a

9.6 ± 0.1a

9.0 ± 0.1a

3.4 Ascorbic acid and K, P, N contents of mushroom (mg/100 g)

Humic acid significantly increased the ascorbic acid contents of fruiting body. Highest concentration of ascorbic acid was recorded in T6 and T5 in white oyster and phoenix oyster. Concentration of K, P and N was higher in T6. The highest amount of potassium (266.6 mg/100 g), phosphorus (122.3 mg/100 g) and nitrogen (84.3 mg/100 g) were noticed treatment T6 in white oyster mushroom. The highest amount of potassium (48.2 mg/100 g), phosphorus (62.3 mg/100 g) and nitrogen (78.6 mg/100 g) were noticed in phoenix oyster cultivated on cotton waste substrate supplemented with 10 mM humic acid (Table 3). Mean value (n = 3) in the same column with the same following letter do not significantly differ (p < 0.05). (T1 = Control, T2 = 2 mM/L humic acid, T3 = 4 mM/L humic acid, T4 = 6 mM/L humic acid, T5 = 8 mM/L humic acid, T6 = 10 mM/L); V1 (P1) = White oyster mushroom; V2 (P3) = Phoenix oyster mushroom.

Treatments

Ascorbic acid (mg/100 g)

K (mg/100 g)

P (mg/100 g)

N (mg/100 g)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

T1

32.1 ± 2.1c

32.1 ± 2.1c

150.3 ± 2.5f

20.3 ± 3.5 cd

41.3 ± 3.2e

24.6 ± 3.5e

49.6 ± 2.5e

40.0 ± 2e

T2

33.5 ± 0.4bc

33.4 ± 1.5bc

180.6 ± 3.0e

18.3 ± 3d

64.6 ± 3.5d

27.6 ± 2.5e

60.3 ± 3.5d

45.0 ± 3de

T3

33.8 ± 0.1bc

33.5 ± 0.4bc

200.3 ± 5.5d

30.3 ± 3.5bc

80.0 ± 3c

33.3 ± 2.0d

60.5 ± 3 cd

50.0 ± 3 cd

T4

34.3 ± 0.4b

34.0 ± 0.4abc

220.3 ± 3.5c

40.0 ± 4ab

95.3 ± 2.5b

41.3 ± 3.2c

70.3 ± 2.5bc

54.6 ± 3.5c

T5

44.4 ± 0.4a

34.6 ± 0.2ab

245.3 ± 4.5b

45.3 ± 2.5a

118.0 ± 3a

57.2 ± 2.3b

75.0 ± 3b

62.3 ± 1.5b

T6

44.8 ± 1.5 a

35.6 ± 0.3a

266.6 ± 3.0a

48.2 ± 2.0a

122.3 ± 1.5a

62.3 ± 2.0a

84.3 ± 3.5a

78.6 ± 3.5a

3.5 Biological efficiency (%)

Biological efficiency (BE) is the ratio of fresh edible weight of mushroom to dry substrate weight expressed in %. Humic acid significantly increased the biological efficiency in two strains of oyster mushroom. Highest biological efficiency was observed in T6 and T5 followed by T1. Highest BE was recorded in phoenix oyster as compared to white oyster mushroom (Table 1).

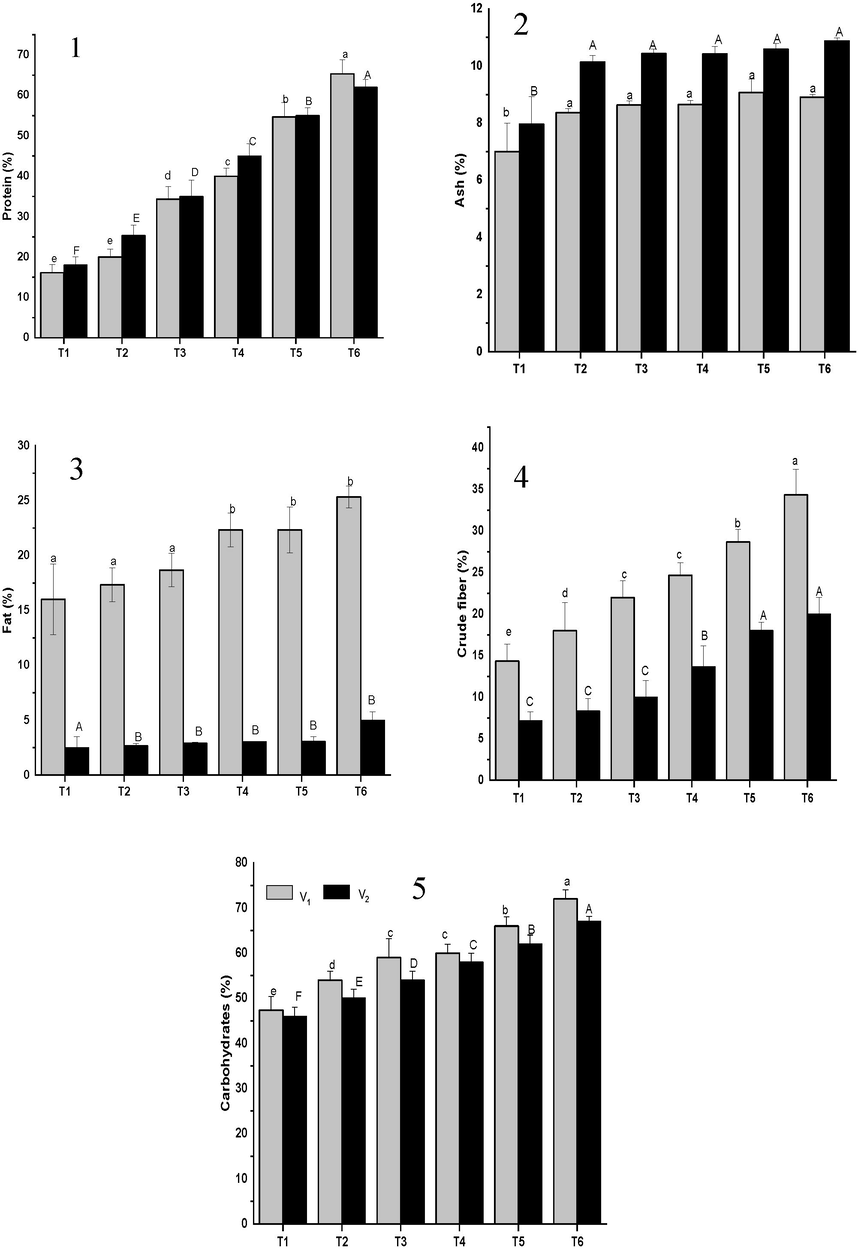

3.6 Proximate analysis (%)

Carbohydrate concentrations of fruiting body were examined between 46% and 72%, depending upon the diverse treatments of HA in substrate. The highest amount of crude protein noted in treatment T6 as compared to control (Fig. 1) By the application of humic acid enriched with cotton waste low level of fat (2.66%) was noticed in T6 in variety V2P3 and in case of variety (V1P1) 16% fats were observed (Fig. 1) Maximum ash content (10.8%) was noticed in T6 in V2P3, while in variety (V1P1), T6 and T5 gave the highest ash content as compared to control. The carbohydrates, fibers, crude protein, fat, ash contents of mushroom were significantly altered by different concentrations of HA (Fig. 1).

Protein (%) (1); Ash content (%) (2); Fat (%) (3); Crude Fiber (%) (4); Carbohydrates (%) (5) of two strains of Oyster mushroom cultivated on different concentration of humic acid enriched with cotton waste. (T1 = Control (100% cotton waste only), T2 = 2 mM/L humic acid, T3 = 4 mM/L humic acid, T4 = 6 mM/L humic acid, T5 = 8 mM/L humic acid, T6 = 10 mM/L); V1 (P1) = White oyster mushroom; V2 (P3) = Phoenix oyster mushroom.

3.7 Mineral contents in mushroom (mg/kg)

Cotton waste enriched with various level of HA significantly affected Zn, Cu, Mg, Mn, Na, Fe and Ca in fruiting body of mushroom (Table 4) Different concentrations of HA on cotton waste substrate increased the mineral contents of fruiting body in both varieties of oyster mushroom. The highest value for mineral contents was observed in T5 and T6, including Zn (28.0 mg/kg), Cu (74.0 mg/kg), Mg (203.4 mg/kg), Mn (28.1 mg/kg), Na (77.6 mg/kg) Fe (550.8 mg/kg) and Ca (362.0 mg/kg) (Table 4) on dry weight basis. Mean value (n = 3) in the same column with the same following letter do not significantly differ (p < 0.05). (T1 = Control, T2 = 2 mM/L humic acid, T3 = 4 mM/L humic acid, T4 = 6 mM/L humic acid, T5 = 8 mM/L humic acid, T6 = 10 mM/L); V1 (P1) = White oyster mushroom; V2 (P3) = Phoenix oyster mushroom.

Treatments

Zn (mg/kg)

Cu (mg/kg)

Mg (mg/kg)

Mn (mg/kg)

Na (mg/kg)

Fe (mg/kg)

Ca (mg/kg)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

V1(P1)

V2(P3)

T1

6.0 ± 1e

10.0 ± 2d

47.2 ± 2e

16.6 ± 2.5d

90 ± 5f

150.3 ± 2.5e

13.6 ± 1.5d

13.6 ± 1.5d

50.3 ± 2.5d

50.3 ± 2.5d

300 ± 5f

251.3 ± 7e

249.3 ± 4.0f

150 ± 5e

T2

9.3 ± 1.5d

13.3 ± 2.5d

52.3 ± 2.5d

20.6 ± 2d

102.6 ± 6.4e

159.3 ± 4d

17.0 ± 2 cd

17.0 ± 2 cd

59.6 ± 2.5c

59.6 ± 2.5c

350 ± 3e

264.6 ± 4.5d

274.3 ± 4.0e

174.3 ± 4.0d

T3

12.3 ± 2.1bc

17.6 ± 2.1c

59.6 ± 2.5c

28.3 ± 3.5c

115 ± 5d

181 ± 3.6c

18.6 ± 1.5c

18.6 ± 1.5c

65.3 ± 2.5bc

65.3 ± 2.5bc

401 ± 3.6d

271 ± 3.6d

300 ± 10d

198.0 ± 8.1c

T4

10.3 ± 1.5 cd

22.0 ± 2.6b

63.3 ± 2.5bc

37.0 ± 2b

127.6 ± 2.5c

190 ± 3b

20 ± 2bc

20 ± 2bc

68.6 ± 3.5ab

68.6 ± 3.5ab

451 ± 3.6c

291 ± 3.6c

316 ± 7.6c

211.6 ± 7.6b

T5

13.0 ± 1b

24.6 ± 3.0ab

65 ± 2b

40.0 ± 3ab

149.3 ± 4b

192.3 ± 3.05b

22.3 ± 1.5b

22.3 ± 1.5b

77.0 ± 9.6a

77.0 ± 9.6a

501 ± 3.6b

308 ± 2.6b

340 ± 10b

225 ± 5a

T6

15.6 ± 1.5a

28.0 ± 2a

74 ± 2.8a

44.6 ± 3.5a

165.9 ± 2.6a

203.4 ± 4.1a

28.1 ± 3a

28.1 ± 3a

75.7 ± 3a

75.7 ± 3a

550.8 ± 3.3a

332.1 ± 2.2a

362 ± 4.3a

227.1 ± 7.0a

3.8 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy is vastly technique that gives the detailed information about organic compounds and functional group present in the mushrooms, that can be observed by wave number of bands. Different FTIR absorption peaks distinguished variation in nutritional contents of white and phoenix oyster mushroom in response to various levels of HA. Considerable variation was observed in absorption spectrum of both oyster mushroom varieties for important nutritional components i.e. carbohydrates, fatty acids, proteins, alkanes, alkynes and hydroxyl group. The FTIR spectral area of both verities of oyster mushroom demonstrated characteristics features in two regions. The first region range, between (4000 – 1800 cm−1). Important spectral peaks in white oyster (V1P1) were 3302, 3289, 2920, 2918, 2853, 2151, 2119 cm-1, that may be allocated to O–H, CH3, - CH2 lipids, C≡C and C–H group. The second region, between (1500–750 cm−1) is consisted of carbonyl group and C⚌C double bond. Differentiated bands were observed in spectrum of white oyster s(V1P1) as compared to control, 3289 and 3202 (O–H and C–H), 1617 (protein), 1146 and 1015 cm−1 (C-O bond, β (1 → 3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide) (Table 5). Highest peaks value in spectra observed in (V1P1T6 and V2P3T6) (Table 5); Supplementary figures S2 (A-L). T1 = Control (100% cotton waste only), T2 = 2 mM/L humic acid, T3 = 4 mM/L humic acid, T4 = 6 mM/L humic acid, T5 = 8 mM/L humic acid, T6 = 10 mM/L humic acid); V2 (P3) = Phoenix oyster mushroom

V1(P1)T1

V1(P1)T2

V1(P1)T3

Frequency

Band assessment

Frequency

Band assessment

Frequency

Band assessment

2922

C–H

2922

C–H

2924

CH3

2186

CH3, - CH2 lipids

2357

CH3, - CH2 lipids

2853

CH3, - CH2 lipids

1958

O–H bond

2273

CH2 Lipids

2163

C≡C

1943

O–H bond

2249

CH3

2037

O–H bond

1584

Amide I, chitosan

1703

Ester group, C-O

1979

CH2, Fatty acid

1518

Protein

1625

Carbonyl group

1578

Amide I, Protein

1459

CH2

1597

Amide I, chitin

1522

Amide II, protein

1405

C-O bond

1459

CH2

1457

CH2

1375

polysaccharide

1401

C-O

1399

C-O bond, β (1 → 3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

1142

C-O

1364

Polysaccharides

1203

C-O bond

1015

C-O Protein

1148

C-O bond, β (1 → 3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

1146

C-O bond, β (1 → 3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

1013

C-O Protein

1012

C-O

846

α-Glycosides

V1(P1)T4

V1(P1)T5

V1(P1)T6

Frequency

Band assessment

Frequency

Band assessment

Frequency

Band assessment

3263

O–H AND C–H

3356

O–H AND C–H

3481

O–H AND C–H

2920

C–H

2920

C–H

3408

O–H bond

2853

CH3

2135

C≡C alkyne

3375

O–H AND C–H

2160

CH2

1899

C⚌O carbonyl stretching of saturated aliphatic esters

3352

O–H AND C–H

2833

CH3 bond

1578

Amide I, Protein

3339

O–H AND C–H

1779

C⚌O carbonyl stretching of saturated aliphatic esters

1507

Amide I, protein

2924

CH3

1617

Amide II, Protein

1399

C⚌C bond

2857

CH3, - CH2 lipids

1397

C⚌C bond

1146

C-O bond, β (1 → 3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

2135

C≡C alkyne

1364

C⚌C bond

1021

C-O bond, β (1 → 3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

1578

Amide II, chitosan

V2(P3)T1

V2(P3)T2

V2(P3)T3

T1= Control (100% cotton waste only), T2 = 2 mM/L humic acid, T3= 4mM/L humic acid, T4 = 6 mM/L humic acid, T5 = 8 mM/L humic acid, T6 = 10 mM/L humic acid; V1 (P1)) = White oyster mushroom.

Frequency

Band assessment

Frequency

Band assessment

Frequency

Band assessment

2918

C–H

2918

C–H

2920

C–H

2853

CH3, - CH2lipids

2853

CH3, - CH2lipids

2855

CH3, - CH2lipids

2169

C≡C

2078

O–H bond

2156

C≡C

2143

C≡C

1817

C⚌O carbonyl stretching of saturated aliphatic esters

1929

Amide II, chitosan

1617

Amide II, chitosan

1459

Amide II, chitosan

1891

C⚌O carbonyl stretching of saturated aliphatic esters

1578

Amide II, chitosan

1399

Symmetric bending of aliphatic CH3, triterpene compounds (CH2⚌CH-CH3)

1604

Amide I, chitosan

1146

C-O-C glycoside

1375

Symmetric bending of aliphatic CH3, triterpene compounds (CH2⚌CH-CH3)

1399

Symmetric bending of aliphatic CH3, triterpene compounds (CH2⚌CH-CH3)

1015

C-O bond, β (1→3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

1146

C-O-C glycoside

1366

Symmetric bending of aliphatic CH3, triterpene compounds (CH2⚌CH-CH3)

1015

C-O bond, β (1→3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

1146

C-O-C glycoside

1032

C-O bond, β (1→3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

1017

C-O bond, β (1→3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

V2(P3)T4

V2(P3)T5

V2(P3)T6

Frequency

Band assessment

Frequency

Band assessment

Frequency

Band assessment

2920

C–H

3289

O–H AND C–H

3302

O–H AND C–H

2853

C–H

2922

C–H

2924

C–H

2197

C≡C

2853

CH3, - CH2lipids

2851

C–H

2137

C≡C

2096

O–H bond

2119

C≡C alkyne

2050

O–H bond

1625

Amide I, chitin

2094

O–H bond

1610

Amide I, chitin

1399

Amide I, chitin

1636

Amide I, chitin

1399

Polysaccharide

1015

C-O bond, β (1→3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

1541

Amide II, chitosan

1375

βglucan

1252

Lipids, Protein

1015

C-O bond, β (1→3) glucan, cell wall, polysaccharide

4 Discussion

4.1 Time to spawn initiation, 100% mycelium growth and pinhead formation

There was no significant effect of different level of HA on days to spawn growth initiation. According to Baysal et al. (2003) humic acid is the source of nitrogen, both high and low nitrogen contents reduce the growth of mycelia growth. The high C/N ratio in the substrate helps to increase the mycelium growth (Hoa et al., 2015). Mushroom growth mainly depends upon the different factors like nature of substrate, spawn rate, fertility of substrates, distribution of spawn and abiotic factors like humidity, light intensity, temperature, level of oxygen and carbon dioxide and moisture percentage during incubation period (Hassan et al., 2010). Fertile substrate enriched with macro and micro nutrients causes early initiation of pinhead and reduces the time to harvestable produce (Singh et al., 2011). Our results declared that HA treatment took less for pinheads’ formation as compared to control.

4.2 Time to maturity of flushes and yield (g)

The total yield obtained by first flush is higher than subsequent flushes. In the second and third flush, mushroom quality is lower as compared to the first flush. Increasing in the number of flushes decreases the yield acquired from substrate due to the less nutrient’s accessibility in the substrate (Rizki and Tamai, 2011). In tomato, humic acid is reported to enhance vegetative growth, fruit yield and quality (Kazemi, 2014). Our results correlate with Prakash et al. (2010) reveal that supplementation of substrate with HA increases the yield in white oyster mushroom.

4.3 Reducing, non-reducing and total sugars and total soluble solid

In present study, humic acid significantly increased the TSS of fruiting body (Kazemi, 2014). The fruit quality, sweetness and taste are bounded to sugar contents like glucose, sucrose and sorbitol in fruit. These factors determined the fruit quality and its market value. Moreover, sucrose plays important role in activation anti-oxidization system, regulation of osmotic pressure, cell membrane stabilization and other metabolic pathways (Nishizawa et al., 2008). Increasing humic acid concentration significantly increases the total, reducing and non-reducing sugars in cucumber plant (Unlu et al., 2011). We observed similar increasing trend in our study.

4.4 Nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and ascorbic acid contents of mushroom

Different levels of HA notably affected mycelia growth rate spawn growth, pinhead’s and fruiting body formation, protein contents and flush yield (Elhami et al., 2008). These results correlate that nitrogen content of lettuce plant increase in response to HA application (Haghighi et al., 2010).

For the completion of biochemical reaction within cells of mushrooms phosphorus works as a co-factor (Khan et al., 2007). Quality of mushroom depends upon the phosphorus availability (Beyer and Muthersbaugh, 1996). The HA considered to increase the uptake of nutrients like P, Ca, and Mg making it more mobile and available to plant root system (Wang et al., 1997).

Potassium plays the important role in different mechanism such as growth, carbohydrates metabolism, ionic balance, enzyme activity and cap and gills discrimination (Griffin, 1996). Humic acid considered to increase the K uptake. The HA increases the N and K concentrations in the roots of tomatoes (Turkmen et al., 2004). Our results are in accordance with Kazemi (2014) who studied and found the increase in TSS and Vitamin C in tomato plant as a result of HA application.

4.5 Biological efficiency (%)

Bhattacharjya et al. (2014) reported that BE of mushroom increases if substrate is supplemented with different chemicals. Similar results were observed by Kirbag and Akyuz (2008) regarding an increase in BE of oyster mushroom at various biological structures of substrate along with supplementation of different chemicals.

4.6 Proximate analysis (%)

Karakurt et al. (2009) investigated that different applications of HA influenced total yield and carbohydrate contents of pepper. Organic fertilizer like humic acid increases the crude protein in pumpkin seed (Jariene et al., 2007). The HA is rich source of nitrogen contents which helps to decrease the fat contents in pumpkin seed. Our results correlate with Jariene et al. (2007) stating that supplementation of substrate with HA increases the crude fiber, decrease fat in pumpkin seed. Our results of ash content are similar to Prakash et al. (2010).

4.7 Mineral contents in mushroom (mg/kg)

Atiyeh et al. (2002) demonstrated that nutrints uptake in tomato plants is significantly improved through HA application. Lime soil treatment with HA enhances absorption of Zn, Cu and Mn in maize crop (Hakan et al., 2010). Nikbakht et al. (2008) revealed that applying the humic compound in cut gerbera flowers increases the uptake of Ca. The HA application improved absorption of minerals (N, P, K, Mg, Fe and Ca) in cucumber and gerbera plants (Behzad, 2014; Nikbakht et al., 2008). We also noted similar increasing trends in our study’s results.

4.8 FTIR characterization

The presence of several functional groups of different biochemical compounds was noticed by FTIR spectroscopy (Supplementary Figs. S2 (A-L). Oyster mushrooms contained high nutritional profile like as, proteins, carbohydrates, macro and microelements with less fat. Absorption bands and spectrum formed by FTIR could properly explained phytochemical analysis relied on functional groups (Muhammad et al., 2019; Ibrahim et al., 2019: Ghramh et al., 2019b). Alcohols, alkyne, and ketone were detected by FTIR spectroscopy (Ghramh et al., 2019a). Moreover, FTIR spectra are proved to be suitable means for estimation of tiny structures in interactions between metallic nanoparticles and biomolecules (Ghramh et al., 2019c). The importance of FTIR is capability of particular characterization of starch, sugars, fats, proteins, nucleic acid and other functional groups (O'Gorman et al., 2010). Some previous work described chemical compositions for various species of Amanita, king oyster, truffles and Agaricus bisporus by FTIR spectra (Zhao et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2019; Muhammad et al., 2019). The present study illustrated that various concentrations of HA highly influenced the nutritional quality of both strains of oyster mushroom.

5 Conclusion

This present study demonstrated that oyster mushroom cultivated on cotton waste enriched with humic acid; provided a favorable media for mushroom growth with significant increase in macro & micro nutrients, Reducing and non-reducing sugar, TSS, Vitamin C, carbohydrates, crude protein, ash and fiber contents. Hence, addition of humic acid in substrate provided better results in yield, BE and mushroom quality. On the other hand, it provided maximum nutritional value and significantly decreased the production-cost. For future aspects, humic acid could be an effective substance for growing quality mushrooms on commercial scales, especially the oyster mushroom.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers supporting project number (RSP-2020/190) King Saud University, Riyadh Saudi Arabia.

We are also thankful to the Chinese government scholarship council, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing China, and University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan for providing an environment of learning.

References

- The effect of commercial humic acid on tomato plant growth and mineral nutrition. J. Plant Nutr.. 1998;21(3):561-575.

- [Google Scholar]

- AOAC, 1995. Official methods of analysis. Association of official analytical chemists. 16th Ed. Arlington, VA.

- Uptake of Cr3+ from aqueous solution by lignite-based humic acids. Bioresour. Technol.. 2008;99:7597-7605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of different lignocellulosic wastes on Hericium americanum yield and nutritional characteristics: effect of lignocellulosic wastes on Hericium americanum. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2017;97(2):606-612.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of humic acids derived from earthworm-processed organic wastes on plant growth. Bioresour. Technol.. 2002;84(1):7-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yield evaluation of Lentinuss quarosulus, on selected sawdust of economic tree species supplemented with 20% oil palm fruit body fibers. Asian J. Plant Sci.. 2007;11:1098-1102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cultivation of oyster mushroom on waste paper with some added supplementary materials. Bioresour. Technol.. 2003;89:95-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Foliar application of humic acid on plant height in Canola. APCBEE Proc.. 2014;8:82-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutrient supplements that influence later break yield of Agaricus bisporus. Can. J. Plant Sci.. 1996;76(4):835-840.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of different saw dust substrates on the growth and yield of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Iosrjavs. 2014;7(2):38-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medicinal Value of the Genus Pleurotus (Fr.) P.Karst. (Agaricales s.l., Basidiomycetes) Int. J. Med. Mushrooms. 1999;1(1):69-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of substrate type, Different level of nitrogen and manganese on growth and development of oyster mushroom (Pleuorotus florida) Dynamic Biochem. Process Biotechnol. Mol. Biol.. 2008;2:34-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yield, size and bacterial blotch resistance of Pleurotus eryngii grown on cottonseed hulls/oak sawdust supplemented with manganese, copper and whole ground soybean. Bioresour. Technol.. 2007;98(10):1898-1906.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fasidi, I.O., Kadiri, M., Jonathan, S.G., Adenipekun, C.O., Kuforiji, O.O., 2008. Cultivation of Edible Tropical Mushrooms. pp. 29-40.

- Ghramh, H.A., Khan, K.A., Ibrahim, E.H., 2019a. Biological activities of Euphorbia peplus leaves ethanolic extract and the extract fabricated gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). Molecules 24, 1431.

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using propolis extract, their characterization, and biological activities. Sci. Adv. Mater.. 2019;11(6):876-883.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ghramh, H.A., Khan, K.A., Ibrahim, E.H., Setzer, W.N., 2019c. Synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using Ricinus communis Leaf ethanol extract, their characterization, and biological applications. Nanomaterials 9, 765.

- Fungal Physiology. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1996.

- Haghighi, M., Kafi, M., Fang, P., and Gui-xiao, L., 2010. Humic acid decreased hazardous of cadmium toxicity on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Vegetable Crops Research Bulletin 72, 49-61.

- Effect of foliar-applied humic acid to dry weight and mineral nutrient uptake of maize under calcareous soil conditions. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal.. 2010;42(1):29-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cultivation of the king oyster mushroom (Pleurotus eryngii) in Egypt. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci.. 2010;4:99-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of different substrates on the growth, yield, and nutritional composition of two oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus cystidiosus) Mycobiology. 2015;43:423-434.

- [Google Scholar]

- Official and Tentative Methods of Analysis. 1960;Vol. 9:320-341.

- Cellular proliferation/cytotoxicity and antimicrobial potentials of green synthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using Juniperus procera. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2019;26(7):1689-1694.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of fertilizers on oil pumpkin seeds crude fat, fibre and protein quantity. Agron. Res.. 2007;5:43-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collection, morphological characterization and nutrient profile of some wild mushroom from Akok, Ondo state, Nigeria. Natural Products. 2011;7:128-136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Feasibility of using olive mill effluent (OME) as a wetting agent during the cultivation of oyster mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus, on wheat straw. Bioresour. Technol.. 2008;99(1):164-169.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of foliar and soil fertilization of humic acid on yield and quality of pepper. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B - Soil Plant Sci.. 2009;59(3):233-237.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of foliar application of humic acid and calcium chloride on tomato growth. Bull. Environ. Pharmacol. Life Sci.. 2014;3:41-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modulation of agronomic and nutritional response of Pleurotus eryngii strains by utilizing glycine betaine enriched cotton waste. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2019;99(15):6911-6921.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms in sustainable agriculture — a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev.. 2007;27(1):29-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of various agro-residues on growing periods, yield and biological efficiency of Pleurotus eryngii. J. Food Agric. Environ.. 2008;6:402-405.

- [Google Scholar]

- MAPYA, 1998. Métodosoficiales de análisisen la Union Europea, in Secretaría General Técnica.Ministerio de Agricultura PyA, ed. by DiarioOficial delas Comunidades Europeas. Tomo 1. Neografis, S.L, Madrid, Spain, p. 495.

- Identification of resistance to cobweb disease caused by Cladobotryum mycophilum in wild and cultivated strains of Agaricus bisporus and screening for bioactive botanicals. RSC Adv.. 2019;9(26):14758-14765.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between molecular characteristics of soil humic fractions and glycolytic pathway and krebs cycle in maize seedlings. Soil Biol. Biochem.. 2007;39(12):3138-3146.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of commercial humic acid on plant growth, nutrients uptake and postharvest life of gerbera. J. Plant Nutr.. 2008;31:2155-2167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiol.. 2008;147(3):1251-1263.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and chemometric data analysis to evaluate damage and age in mushrooms (agaricus bisporus) grown in Ireland. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2010;58(13):7770-7776.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sustainability of selected supplemented substrates for cultivation of Kenyan native wood ear mushrooms (Auricularia auricular) Am. J. Food Technol.. 2011;6:395-403.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of fractions of coal-derived humic substances on seed germination and growth of seedlings (Lactuga sativa and Lycopersicum esculentum) Biol. Fertil. Soils. 1993;16(1):11-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, P., Aashish, B.A., Neil, J., Kenny, Sivasubramnian., 2010. Effect of humic acid on Pleurotus ostreatus mushroom cultivation and analysis of their nutrient contents. Research Journal of Agriculture and Biological Sciences 6, 1067-1070.

- Ranganna, S., 1986. Hand book of analysis and quality control for fruit and vegetable product,. pp. 25-26.

- Effects of different nitrogen rich substrates and their combination to the yield performance of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2011;27(7):1695-1702.

- [Google Scholar]

- Agro-industrial residues influence mineral elements accumulation and nutritional composition of king oyster mushroom (Pleurotus eryngii) Sci. Hortic.. 2017;225:327-334.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mushrooms Cultivation. Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Chambaghat, Solan: Marketing and Consumption. Directorate of Mushroom Research; 2011.

- Principles and Procedures of Statistics, a Biometrical Approach. Tokyo, Japan: McGraw-Hill Kogakusha Ltd; 1980.

- Humic substances biological activity at the plant-soil interface: from environmental aspects to molecular factors. Plant Signaling Behav.. 2010;5(6):635-643.

- [Google Scholar]

- Calcium and humic acid affect seed germination, growth, and nutrient content of tomato (Lycospericon esculentum L.) seedlings under saline soil conditions. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica. 2004;54:168-174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in fruit yield and quality in response to foliar and soil humic acid application in cucumber. Scientific Res. Essays. 2011;6:2800-2803.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of humic acid on the availability of phosphorus fertilizer in alkaline soils. Soil Use Manage.. 1997;11:99-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- The cultivation of mushroom. Mushroom J. 188, 665–674. Jonathan, S.G., Esho, E.O., 2010. Fungi and Aflatoxin detection in two oyster mushrooms Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus pulmonarius from Nigeria. Electron. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 1988;9:1722-1730.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cultivation of the king-oyster mushroom Pleurotus eryngii (DC.:Fr.) Quél. on substrates deriving from the olive-oil industry. Int. J. Med. Mushroom. 2005;7(3):486-487.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D., Liu, G., Song, D., Liu, J-h., Zhou, Y., Ou, J et al., 2006. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Study of Truffles, in ICO20: Biomedical Optics. International Society for Optics and Photonics, Bellingham, USA. p. 60260H.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2020.08.016.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: