Translate this page into:

Effect of gelatinous spongy scaffold containing nano-hydroxyapatite on the induction of odontogenic activity of dental pulp stem cells

⁎Corresponding authors. maleki.s.89@gmail.com (Solmaz Maleki Dizaj), eftekharia@tbzmed.ac.ir (Aziz Eftekhari), kavetskyy@yahoo.com (Taras Kavetskyy)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Tissue engineering methods may be applied for the repair or regeneration of damaged teeth by inducing cell proliferation and differentiation in endodontic regeneration. One of the main factors in tissue engineering is the scaffold used. An ideal scaffold should be able to facilitate predictable tissue development in endodontic regeneration. Thus, tissue engineering requires consideration for the composition and functionality of the scaffold suited for biological applications. The objective of this study was to assess the morphological, physico-chemical, and biological properties of a new gelatin (Gel)-nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA)-based scaffold to be applied in endodontic regeneration. The scaffold containing gelatin and nHA was prepared by a freeze-drying method. Conventional techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD), and dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis were used to evaluate the physico-chemical properties of the fabricated Gel-nHA sponge scaffold. Biological examination for cell survival and differentiation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) was evaluated by the MTT assay and ALP activity techniques, respectively. The produced Gel-nHA scaffold had spongy properties that all functional groups of gelatin and hydroxyapatite were present in the sponge. In biological studies, the viability of the cells grown on Gel-nHA scaffold had no different change from the control group on days 2nd, 4th, and 6th. Besides, after 14 days of cells cultured on Gel-nHA, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity showed a significant increment. In summary, the Gel-nHA scaffold revealed favorable effects on odontogenic activity, implying a potential future for application in endodontic regeneration.

Keywords

Dental pulp stem cells

Gelatin

Nano-hydroxyapatite

Odontogenic activity

Spongy scaffold

Tissue engineering

1 Introduction

Regenerative endodontics is one of the latest endodontic treatment modalities that has recently been presented and has found a position in the area of current dental treatments. However, contradictory results have called into doubt its validity and dependability in endodontic treatments (Bansal et al., 2015). This procedure uses cells with the ability to differentiate, such as stem cells, to try to rebuild lost and necrotic tissues. Despite being innovative and using modern technology, this therapeutic strategy has considerable drawbacks. One of the method's main shortcomings is its inability to regenerate tissues completely (Galler and Widbiller 2020). One of the main aims of the tissue engineering technique is to induce regeneration to heal injured tissues by utilizing bioactive chemicals, cell resources, and scaffolds to restore bone function through the regeneration and adaptation to the host tissue process (Hill et al., 2006, Sharifi et al., 2020a; Sharifi et al., 2020b; Khezri et al., 2021).

Stem cells are defined as cells with self-renewal potential and multi-lineage differentiation (Lavik and Langer 2004, Vahedi et al., 2019, Vahedi et al., 2021). Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) have a high capability for differentiation and for the regeneration of the dentin–pulp complex (Gronthos et al., 2000). Scaffolding functions as a synthetic matrix, enabling cells to proliferate while still performing their specialized function. Natural materials such as chitosan, gelatin (Gel), collagen, hyaluronic acid and fibrin have all been utilized to fabricate scaffolds for tissue engineering (Ahmadian et al., 2020, Sharifi et al., 2021). Cellular scaffolds suited for cell implantation or injection should promote cell survival, induce bioactivity, and increase cell adhesion in the location of cell implantation or injection. In addition, scaffolds are composed of various kinds of polymers, which shield cells from the immune system and allow the exchange of nutrients and waste compounds (Azami et al., 2012, Henkel et al., 2013, Firouzi et al., 2020).

Gel is a natural biopolymer derived from animal skin, bone, and tendon collagen. Gel structures with varying physical and chemical characteristics emerge from differences in collagen supply and manufacturing procedures (Djagny et al., 2001, Alipour et al., 2021). Gel may also improve cell proliferation and differentiation (Zhu et al., 2004, Salamon et al., 2014), such as DPSC adhesion and proliferation, migration, and odontogenic differentiation, which increases mineralization, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, and increases collagen expression (Qu and Liu 2013).

The main inorganic constituent of bone and enamel is hydroxyapatite (HA). HA particles have the ability to induce macrophages to release odontogenic and angiogenic growth factors (Honda et al., 2006, Kilian et al., 2008).

As angiogenesis and bone formation induction are crucial processes in bone regeneration, using nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) in the scaffold makes sense. Adding bioactive elements as fillers to scaffolds may enhance their physical and chemical characteristics; therefore, scaffolds incorporating inorganic and polymeric materials may increase mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and biodegradability (Sharifi et al., 2019). The nHA, which has a chemical and crystal structure similar to bone mineral is considered an excellent scaffolding material (Zakaria et al., 2013). Smaller nHA particles (<100 nm) seem more favorable to the host due to improved interfacial adhesion, cell proliferation, and cell adherence (Jiang et al., 2017).

In assessing the effectiveness of tissue engineering, the qualities of scaffolding are vital in cell survival or induction of differentiation, in addition to evaluate the characteristics of scaffolding. Tissue toxicity generally develops as a result of excessive absorption and the concentration of a chemical exceeding the tissue tolerance threshold and depletion of antioxidants reservoirs (Ma 2004, Ahmadian et al., 2017). According to several investigations, increasing cytotoxicity inhibits tissue regeneration and causes cell death. As a result, an evaluation of the impact of designed scaffolding on cell survival or toxicity is required. Changes in ALP activity must also be monitored to measure bone differentiation in scaffolding (Kanczler and Oreffo 2008, Polini et al., 2014). Several investigations have revealed that this enzyme plays an essential role in mineralizing organic tissue in bone and dental tissue samples (Liu and Chang 2002, Haque et al., 2005). Based on these examples, it is possible to infer that assessing the amount of this marker is critical in evaluating the success and efficacy of tissue engineering.

Thus, the aim of this study was to engineer the gelatin sponge scaffold containing nHA with an odontogenic specificity. Subsequently, this scaffold was studied to determine its effect on cell growth. Finally, the change in the level of ALP activity in DPSCs grown on the engineered scaffold was analyzed to assess longer-term effects.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethics approval

The ethical code of this investigation is IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1400.391, which was accepted by the Ethic Committee of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

2.2 Preparation of scaffold

Gelatin solution was prepared with a 1/10 w/v ratio of gelatin (Sigma Aldrich-USA) and distilled water at 65 °C. Then, the solution was stirred at 35 °C and 1 % w/v of glutaraldehyde (Sigma Aldrich-USA) was added and stirred. The resulting solution was poured into a mechanical stirrer. Then, 10 % w/v of nHA was added to the gelatin solution and stirred for 60 min. The resulting material was placed in a freezer at −20 °C for 24 h. The frozen material was then incubated in a vacuum oven for 24 h and dried.

2.3 Characterization of the scaffold

2.3.1 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphological characteristics of the scaffold were examined using SEM (Razi Company of Tehran, Tehran, Iran). The samples were placed on a SEM plate and subsequently gold-coated in a high-vacuum environment and at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV. The magnification of the SEM was set to 100X.

2.3.2 Particle size

By an argon laser beam in a scattering angle of 90° and at 633 nm, dynamic light scattering (DLS, Malvern, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United Kingdom) was utilized to validate the nanoscale size accuracy of the nHA at 25 °C. The device's specific tube was filled with distilled water to generate a high-quality suspension of scaffolds.

2.3.3 X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The raw materials and the prepared scaffold were evaluated at room temperature utilizing XRD patterns. The patterns of the samples were determined using an X-ray diffractometer (D5000, Siemens, Munich, Bavaria, Germany) set at 5405/1 Å wavelength, 40 kV voltage, and 30 mA. Their patterns were analyzed between zero and sixty 2θ values.

2.4 Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy (FTIR, Shimadzu 8400S-Japan, Kyoto, Japan) was used to identify the functional groups. The samples were combined with IR-grade potassium bromide and pressed using IR pellet production equipment. The wavelengths were then adjusted from 400 to 4000 (cm−1).

2.5 MTT assay

In this study, to evaluate the toxic effect of scaffolding on DPSCs, an MTT assay was used. In order to perform these experiments, DPSCs were purchased from Shahid Beheshti University, which had a low passage number. The prepared scaffold was placed at the bottom of the 96-well plate and then the cells (5 × 103 cell/ well) were added to each well in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) medium containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 % antibiotics. The plates were incubated for 2, 4, and 6 days. Following this, the culture medium was removed and incubated with 200 μl of culture medium. Further, 50 μl of MTT solution (2 mg/ml PBS) was added and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and kept away from light. After the incubation period, the above solution was removed and 200 μl of DMSO was added to each well. Their absorption was read at 540 nm and the percentage of living cells was measured by comparing the control (cells grown in the absence of the scaffold).

2.6 ALP activity

The sterilized scaffolds were put into the 24-well plate, and DPSCs were added to each well (5 × 104 cells/well). ALP activity was assessed after 14 days. Briefly, the wells were washed three times with PBS. A stock solution of cell digestion buffer, which has 1.5 M Tris-HCl, 1 mM ZnCl2, and MgCl2x6H2O, was diluted in a solution of distilled water (1:10) and added to each well. Then, 1 % of Triton X-100 was added to the wells. Then, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and were then stored at 4 °C overnight. Cell lysates were put into samples, vortexed for 2 min, and centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm. Also, about 10 µl of cell lysate mixed with 190 µl of ALP solution (37.1 mg of pNPP in 20 mL of cell assay buffer) was added to each well of the 96-well plate. The sample was shaken at room temperature in the dark for 50 min. The Cytation 5 system was used to measure the absorbance of the ALP activity at 405 nm. The control group was cells grown in the absence of the scaffold.

2.7 Statistical analysis

To establish the significance of the experimental findings, one-way ANOVA and t-test statistical analysis were used for MTT tests and ALP activity tests, respectively. A statistically significant p-value of p < 0.05 was used. Tukey’s post hoc test was used for the analysis between the groups for MTT test.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of scaffold

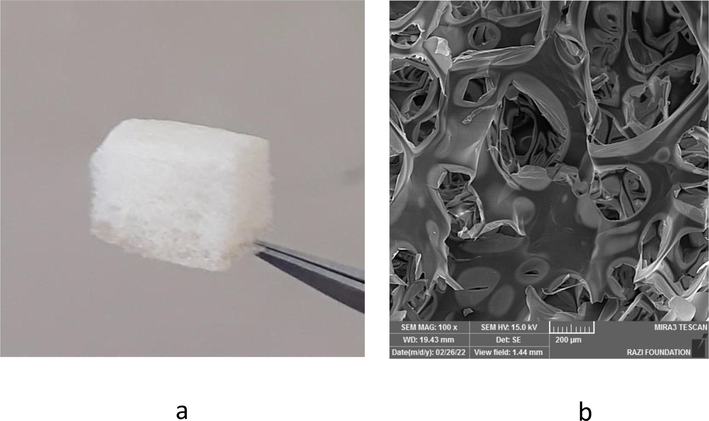

Fig. 1a shows the produced sponge. SEM image of the sponge has presented in Fig. 1b. The microscopic structure of the prepared sponge under SEM showed a porous structure with the micrometric and nanometric pores. The micro/nano-structured porous sponges are recently in the core of attention to use as scaffolds. The micro/nano pores allow for cell mobility and metabolic processes (Sari et al., 2021). Nanometer-scale pores on the surface of the sponge can also leads to surface roughness (Xue et al., 2019).

The produced sponge (a). The SEM image of the sponge (b).

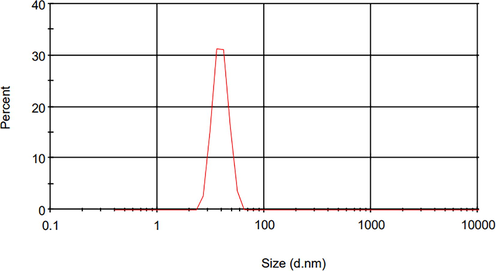

3.2 Particle size

The size distribution for nHA particles is presented in Fig. 2. Based on the results, the mean particle size of 75 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) value of 0.2 shows the relatively monodisperse particle size distributions (Jana et al., 2014). This index shows that values smaller than 0.05 are mostly highly monodisperse. PDI values bigger than 0.7 specify that the sample has a very wide-ranging particle size distribution and is possibly not appropriate to be investigated by the DLS method (Danaei et al., 2018).

The size distribution for nHA particles.

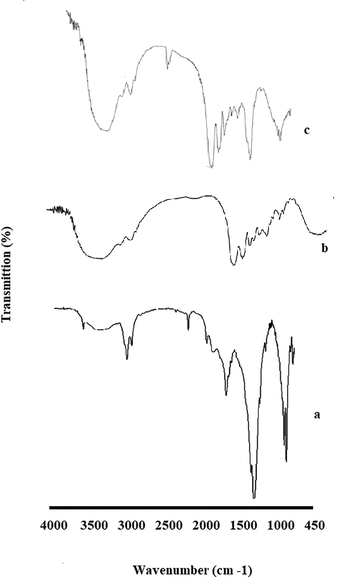

3.3 FT-IR analysis

FTIR results showed that all functional groups of gelatin and HA were present in the sponge (Fig. 3). The amide II peak in the sponge sample was related to gelatin (1634 cm−1) (Tengroth et al., 2005). Also, it was revealed that the broad peak at 3200–3500 cm−1 was linked to the OH group’s tension spectrum (El-Rahman and Al-Jameel 2014). The index peaks were associated with the HA phosphate group at 563 and 602 cm−1 (Hezma et al., 2019).

FTIR results for nHA (a), Gelatin (b) and the prepared sponge (c).

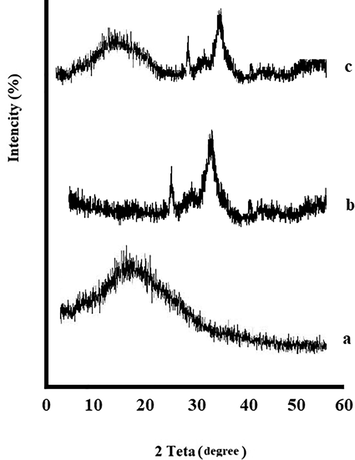

3.4 Identification of crystallinity state

XRD patterns were determined at room temperature for the raw materials and the final product, respectively (Fig. 4). The produced sponge showed the peaks for both materials. In a previous study, XRD results showed that the structure of gelatin was essentially amorphous (Hezma et al., 2019). XRD pattern findings revealed that HA exhibited its index peaks at 26, 31, 39, and 41° according to pervious study (Hezma et al., 2019).

XRD diffraction patterns, Gelatin (a), nHA (b) and the prepared sponge (c).

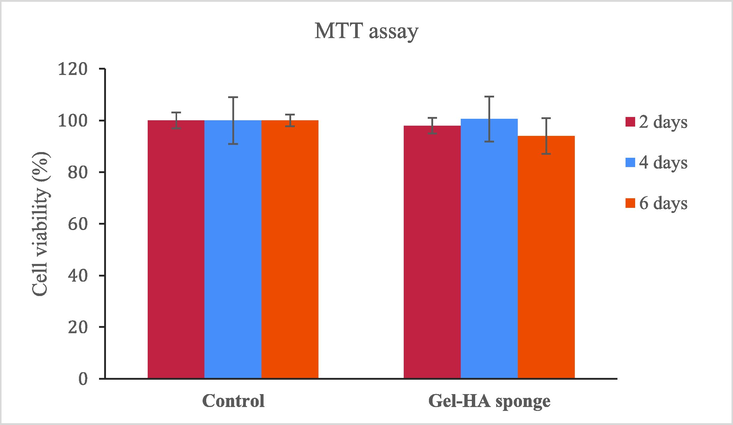

3.5 Cell viability

MTT assay results revealed that sponge was not cytotoxic, similar to the corresponding control groups (Cells were grown in the absence of scaffolds) (p > 0.05) (Fig. 5). Tukey’s post hoc test also showed that there was no significant difference between the groups (p > 0.05). Sadeghinia et al. synthesized nanohydroxyapatite/chitosan/gelatin scaffolds which did not show any cytotoxicity on dental pulp stem cells and had proliferative effect (Sadeghinia et al., 2019). In our previous study, we prepared gelatin-hydroxyapatite nano-fibers which didn’t show the cytotoxic effect on DPSCs and showed a significant proliferative effect (Sharifi et al., 2020a; Sharifi et al., 2020b). The non-toxicity of Gel-HA sponge on DPSCs was consistent with the results of other studies as well (Sharifi et al., 2020a; Sharifi et al., 2020b; Alipour et al., 2021).

The cell viability of seeded DPSCs on the Gel-HA sponge scaffolds.

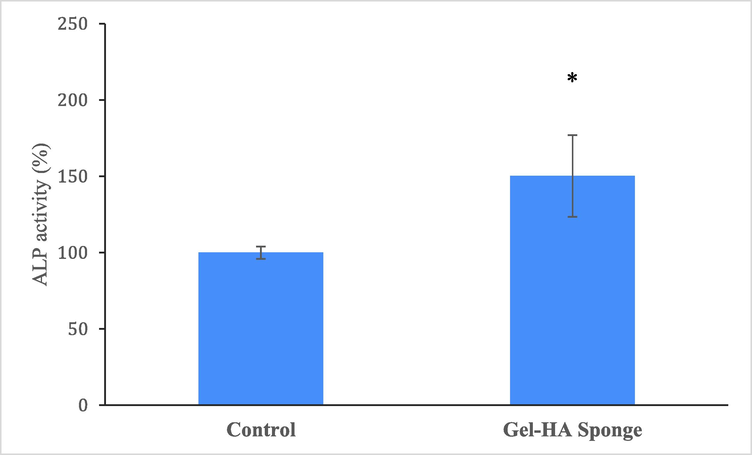

3.6 ALP activity

After 14 days of culture, the ALP activity of DPSCs cultured on Gel-HA rose considerably in contrast to the control groups (p < 0.05). This increase suggests that the DPSCs progressively differentiated into osteoblasts (Fig. 6). A previous study has shown that MSCs seeded on Gel-HA scaffold have a strong bio-mimetic potential as a hard tissue scaffold (Li et al., 2018). The combination of polymeric scaffolds by inorganic particles may induce a positive cellular response compared to neat scaffolds, for example in enhanced cell proliferation and early osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC), as showed by the ALP expression (Raucci et al., 2019). Sadeghinia et al. showed nanohydroxyapatite/chitosan/gelatin scaffolds increased ALP activity of DPSCs after two weeks (Sadeghinia et al., 2019).

The ALP activity in DPSCs seeded on the Gel-HA sponge scaffolds. * shows statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference with control.

4 Conclusions

Our findings showed that the Gel/nHA sponge scaffold, in particular, has the best overall characteristics for endodontic regeneration applications. We believe that because this method of forming organic/inorganic hybrid scaffolds is reasonable and typically performed under mild conditions, while improving bioactive and mechanical properties, such a scaffold will have potential applications in tooth tissue regeneration, drug delivery, and other related medical fields. However, more studies should be conducted over a longer time period to develop the cell/gelatin scaffold build and explore the mechanical and physical properties that will be suitable for endodontic regeneration. In future, organic/inorganic hybrid materials may be accessible as a main part of the biomaterial scaffolds. Such advanced biomaterials can be used as scaffolding blocks with human stem cells in developing bioprinting application, antimicrobial and antioxidant therapy, including drug screening and disease modelling. However, more in vivo and clinical tests are needed to show these abilities.

Acknowledgment

This paper was derived from a thesis provided at the Faculty of Dentistry, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (number 67462). This study was supported financial by the Vice-Chancellor for Research at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. M.G. was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship (BO/00144/20/5) of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The research was supported by the ÚNKP-22-5-SZTE-107 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund. T.K. was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (projects Nos. 0121U109543 and 0122U000874), National Research Foundation of Ukraine (project No. 2020.02/0100 “Development of new nanozymes as catalytic elements for enzymatic kits and chemo/biosensors”), and SAIA (Slovak Academic Information Agency) in the framework of the National Scholarship Programme of the Slovak Republic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Anti-cancer effects of citalopram on hepatocellular carcinoma cells occur via cytochrome C release and the activation of NF-kB. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents). 2017;17(11):1570-1577.

- [Google Scholar]

- The potential applications of hyaluronic acid hydrogels in biomedicine. Drug Res.. 2020;70(1):6-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- The osteogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells in alginate-gelatin/Nano-hydroxyapatite microcapsules. BMC Biotech.. 2021;21(1):1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- A porous hydroxyapatite/gelatin nanocomposite scaffold for bone tissue repair: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed.. 2012;23(18):2353-2368.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current overview on challenges in regenerative endodontics. J. Conserv. Dent.. 2015;18(1):1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(2):57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gelatin: A valuable protein for food and pharmaceutical industries: review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.. 2001;41(6):481-492.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protection of curcumin and curcumin nanoparticles against cisplatin induced nephrotoxicity in male rats. Sch. Acad. J. Biosci.. 2014;2(3):214-223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enzymatically gellable gelatin improves nano-hydroxyapatite-alginate microcapsule characteristics for modular bone tissue formation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A. 2020;108(2):340-350.

- [Google Scholar]

- Galler, K.M., Widbiller, M., 2020. Cell-Free Approaches for Dental Pulp Tissue Engineering. J. Endod. 46 (9S), S143-S149.

- Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2000;97(25):13625-13630.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro study of alginate–chitosan microcapsules: an alternative to liver cell transplants for the treatment of liver failure. Biotechnol. Lett.. 2005;27(5):317-322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bone regeneration based on tissue engineering conceptions—a 21st century perspective. Bone Res.. 2013;1(1):216-248.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and spectroscopic investigations of hydroxyapatite-curcumin nanoparticles-loaded polylactic acid for biomedical application. Egyptian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 2019;6(1):1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing scaffolds to enhance transplanted myoblast survival and migration. Tissue Eng.. 2006;12(5):1295-1304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elevated extracellular calcium stimulates secretion of bone morphogenetic protein 2 by a macrophage cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.. 2006;345(3):1155-1160.

- [Google Scholar]

- Felodipine loaded PLGA nanoparticles: preparation, physicochemical characterization and in vivo toxicity study. Nano Converg.. 2014;1:31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and properties of bamboo fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/poly (lactic-co-glycolic) composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9(5):4890-4897.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteogenesis and angiogenesis: the potential for engineering bone. Eur. Cells Mater.. 2008;15(2):100-114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells via Curcumin-Containing Nanoscaffolds. Stem Cells Int.. 2021;2021:1520052.

- [Google Scholar]

- Observations on the microvasculature of bone defects filled with biodegradable nanoparticulate hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials. 2008;29(24–25):3429-3437.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tissue engineering: current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2004;65(1):1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Small molecules modified biomimetic gelatin/hydroxyapatite nanofibers constructing an ideal osteogenic microenvironment with significantly enhanced cranial bone formation. Int. J. Nanomed.. 2018;13:7167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased viability of transplanted hepatocytes when hepatocytes are co-encapsulated with bone marrow stem cells using a novel method. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology. 2002;30(2):99-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stable biofunctionalization of hydroxyapatite (HA) surfaces by HA-binding/osteogenic modular peptides for inducing osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Biomater. Sci.. 2014;2(12):1779-1786.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nano-Structured Gelatin/Bioactive Glass Hybrid Scaffolds for the Enhancement of Odontogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2013;1(37):4764-4772.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactivation routes of gelatin-based scaffolds to enhance at nanoscale level bone tissue regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.. 2019;7:27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nano-hydroxy apatite/chitosan/gelatin scaffolds enriched by a combination of platelet-rich plasma and fibrin glue enhance proliferation and differentiation of seeded human dental pulp stem cells. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2019;109:1924-1931.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gelatin-based hydrogels promote chondrogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Materials. 2014;7(2):1342-1359.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioceramic hydroxyapatite-based scaffold with a porous structure using honeycomb as a natural polymeric Porogen for bone tissue engineering. Biomater. Res.. 2021;25(1):1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stem cell therapy: curcumin does the trick. Phytother. Res.. 2019;33(11):2927-2937.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemicals impact on osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. BioFactors. 2020;46(6):874-893.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gelatin-hydroxyapatite nano-fibers as promising scaffolds for guided tissue regeneration (GTR): Preparation, assessment of the physicochemical properties and the effect on mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Advanced Periodontology & Implant Dentistry. 2020;12(1):25-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation, Physicochemical Assessment and the Antimicrobial Action of Hydroxyapatite–Gelatin/Curcumin Nanofibrous Composites as a Dental Biomaterial. Biomimetics. 2021;7(1):4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cross-linking of gelatin capsules with formaldehyde and other aldehydes: an FTIR spectroscopy study. Pharm. Dev. Technol.. 2005;10(3):405-412.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vivo articular cartilage regeneration through infrapatellar adipose tissue derived stem cell in nanofiber polycaprolactone scaffold. Tissue Cell. 2019;57:49-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of infrapatellar fat pad-derived Mesenchymal stem cells in Articular cartilage regeneration: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2021;22(17):9215.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: Methods, materials, and applications. Chem. Rev.. 2019;119(8):5298-5415.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanophase hydroxyapatite as a biomaterial in advanced hard tissue engineering: a review. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev.. 2013;19(5):431-441.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endothelium regeneration on luminal surface of polyurethane vascular scaffold modified with diamine and covalently grafted with gelatin. Biomaterials. 2004;25(3):423-430.

- [Google Scholar]