Translate this page into:

Effect of crude methanolic extract of Lawsonia inermis for anti-biofilm on mild steel 1010 and its effect on corrosion in a re-circulating wastewater system

⁎Corresponding authors. malsalhi@ksu.edu.sa (Mohamad S. Alsalhi), abudukeremu@ms.xjb.ac.cn (Abudukeremu Kadier), rajasekargood@gmail.com (Aruliah Rajasekar)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

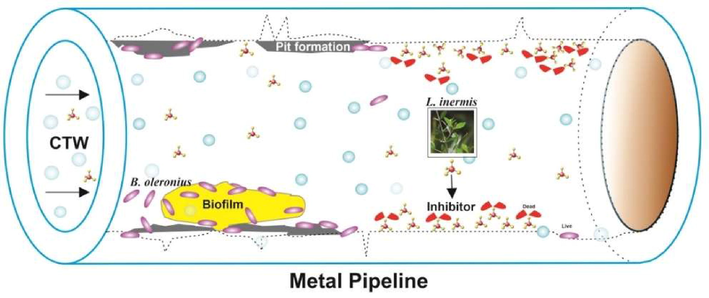

The natural product Catharanthus roseus and Lawsonia inermis leaf extract enhancement in the anti-corrosion potential green corrosion inhibitor (GIC) for Bacillus oleronius EN9 biofilm forms on mild steel (MS) in re-circulating water environment is demonstrated. This re-circulating water was enhancing the corrosion due to the temperature, pH, salinity, and chloride. Therefore, we need to improve the performance of the inhibitors. The chosen GIC inhibition was examined by antibacterial assay, weight loss, surface, and electrochemical analysis. L. inermis has shown the antibacterial activity (75%) against the corrosive bacteria Bacillus oleronius than the C. roseus (44%) optimum concentration of 20 ppm. L. inermis was selected for further studies and it reduces the corrosion rate up to 75 % in the 1% NaCl system. Scanning electron microscopy confirms the formation of the protective film on MS and GC–MS confirmed the presence of complex molecules of L. inermis. Therefore, the current work concluded that green corrosion inhibitor is suitable for the inhibition of biocorrosion of MS in the re-circulating system and a promising alternative for chemical inhibitor.

Keywords

Re-circulating water

Lawsonia inermis

Green inhibitor

Bacteria

1 Introduction

Microbiologically Induced Corrosion (MIC) is the deterioration of a metal surface by microorganism that occurs through metabolic activity of microbes (Rajasekar et al., 2017). These are electrochemical reaction rusting a metal surface and microbial metabolic activity (exo-polymers, enzymes, organic acid, inorganic acids, sulfides, and ammonia, with the oxidation and reduction reaction capacity) which indues the electrochemical reactions (Papadopoulou and Eliades, 2009; Devika et al., 2020; Barbouchi et al., 2020; Satoh et al., 2009). The corrosion causing bacteria adhesion on the metal surfaces which might be releasing metabolic products that are increasing the corrosion reaction on the metal surfaces (Swaroop et al., 2016). Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) contribute an essential bio-factor for development of biofilm on surfaces and leads to increasing the thickness of the film and enter into the biofilm cycle (Javed et al., 2005; Parthipan et al., 2008). Hence, evaluation of scaling and accumulation of microorganisms in cooling tower water system (CTS) can be decided by either occurrence of microorganisms and factors like temperature, alkalinity conductivity and total dissolved ions (Narenkumar et al., 2018). The maximum notable material widely used by industries, commonly using mild steel (MS) which has maximum conductivity (El-Shamy et al., 2009). Numerous studies on MIC deals with MS material (Narenkumar et al., 2017). Metallic oxidization that interprets for 20% pipeline system failure in industries is a possible risk to many industries like gas, oil, processing industries, etc., the major problem was decreased water supply and lead to obstruction of pipeline flow. Further the occurrence of the microbial population has significant economic impact on the industries due to the MIC (Aquaprox, 2009; Narenkumar et al., 2016).

Inhibition of MIC was achieved by reducing the formation of biofilm on surfaces. While selecting corrosion inhibitors/biocide should have the properties like antimicrobial activity, biodegradability (Eco friendly), compatibility with other chemicals, and finally economic feasibility (Gaylarde and Videla, 1992). Most corrosion inhibitor based on quaternary ammonium salts, ethylene glycol, formaldehyde, sodium molybdate, glutaraldehyde used to control the MIC. Even though, those chemicals are non-eco-friendly due to its some extent of toxic to the surrounding environment which are currently big challenges to replace the alternate chemicals (Narenkumar et al., 2017; Queiroz et al., 2005; Saeedet al., 2019; Starosvetsky et al., 2007). Many of these methods are costly (high priced) and unsafe to the environment (due to the toxic chemicals or metals) alongside with supplemental limitations. Hence, natural inhibitors such as plant derivatives are inexpensive, easily available and eco-friendly, they are added in a very lower concentration to treat a metal surface corrosive environment, and therefore the process reduces the corrosion level of a metal surface (Yadav and Dixit, 2019). Currently other inhibitors based on the extracts of plants with antimicrobial properties which are used and termed as eco-friendly to control MIC (Jayaraman et al., 1999). Recently different plant extracts were using against corrosion inhibitor such as Azadirachta indica leaves extract, Watermelon rind extract, Nicotiana tabacum leaves extract, Chromolaena odorata extracts and Black pepper extract ect, (Shaily et al., 2014; Aribo et al., 2016; Raja and Sethuraman, 2008). The name “eco-friendly inhibitor or green inhibitor” refers to the material that has biocompatibility is related to the behavior of biomaterials in various contexts of nature. Similar to the overall classification of the green inhibitor can also divide into two types, namely organic and inorganic green inhibitors. Commonly green inhibitors are excellent to inhibitors under several corrosive environments it has many benefits for plant extracts (Green inhibitor) low cost and environmentally safe non-toxic, so these are the main advantages of using plant extracts, due to the renewability of its resources (Kesavan et al., 2012).

Recently, many researchers focused on the green inhibitor, whereas limited work has been published on the consent of MIC. Hence, the present investigation, the green corrosion inhibitor (GIC) behavior, and their possible mechanism were examined by the weight loss, electrochemical studies (EIS), surface morphology (scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Gas-chromatography mass spectroscopy (GCMS)) respectively. This study is proven the use of green corrosion inhibitor to control MIC in the re-circulating water system.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Microorganism

Biocorrosion bacterium Bacillus oleronius EN9 was used in the current study which was isolated from biofilm samples of cooling tower water material and the accession number was KR183880 (Narenkumar et al., 2018). The fresh culture of the EN9 was prepared by using sterile nutrient broth (Himedia, Mumbai, India) and subculture repletely to get pure cultures and the growth condition was pH 7.0, 37 °C for 24 h.

2.2 Preparation of aqueous plant extract

C. roseus and L. inermis leaves were collected from herbal garden, Vellore and kept for dry in a room shadow for few days and further used for the extraction. The extract of C. roseus and L. inermis was prepared by as described earlier (Ostovari et al., 2009). Fresh C. roseus and L. inermis leaves were surface cleaned with deionised water and grained with methanol (99.9%). The liquid thus acquired was filtered via Whatman filter paper to remove the dregs. The filtered solution was subjected to rotary evaporated and sterilized using autoclave prior to the further work and stored at 4 °C. The major constituent of L. inermis were lawsone, gallic, dextrose, and tannic acid as reported (Ostovari et al., 2009).

2.3 Evaluation of the anti-microbial activity of crude extract of plant by agar-well diffusion assay and biofilm analysis

The minimal inhibition concentration of C. roseus (Inhibitor I) and L. inermis (Inhibitor II) with EN9 was determined by agar diffusion assay (Lalpuria et al., 2013). C. roseus and L. inermis with various concentration of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 ppm were used and measured the zone of inhibition and minimal inhibition concentration as described earlier reported by AlSalhi et al. (2016).

2.4 Biocorrosion studies

Biocorrosion studies were performed as procedure described by Aruliah and Ting, 2014; Rajasekar and Ting, 2014. The MS1010 was used in the composition with minor modifications as follow C 0.2%, Fe 0.03%, Mn 0.2%, P 0.50%, S 0.03%, and remaining iron. The anti-bio corrosive studies were conducted in six systems include biotic/ abiotic systems (Table 1) as system I-V. For WL and EIS, the polished MS coupons with dia 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm and 0.1 cm2 and rectangular coupons (2 mm thickness). The biocorrosion coupons before the experiment was subsequently sterilized with the 70% ethanol for 10mininsonicator. Finally, sterilized by UV light (220 nm) for 20 min prior to exposure (Xu et al., 2016). Each system consist of three coupons and the experiments was conducted as triplicate. Biocorrosion experiment was incubated at 37 °C for 15 days and the weight loss of the metal coupons were accounted for corrosion rate as per National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE) (McIntyre and Mercer, 2010). The surface morphology of the metal samples was characterized by SEM (Rajasekar and Ting, 2010) and the protective film confirmation by GCMS (El-Etre et al., 2005). Surface biofilm was collected using sterile spatula and dissolved in methanol. The dissolved solution was injected in the GC–MS.

S. No

Systems

Weight loss (g)

Corrosion rate (mm/y)

Inhibition Efficiency (%)

1

Control system

400 mL in sterile Cooling tower water (CTW) consist of 1% of nutrient broth (NB).0.087 ± 0.001

1.07

–

2

System I:

400 mL in sterile CTW consist of 1% of NB with EN9 (1 × 10−4 CFU/mL).0.175 ± 0.003

2.1

–

3

System II:

400 mL in sterile CTW consist of 1% of NB with Inhibitor I0.041 ± 0.001

0.63

44

4

System III:

400 mL in sterile CTW consist of 1% of NB with Inhibitor II0.021 ± 0.004

0.26

75

5

System IV:

400 mL in sterile CTW consist of 1% of NB with EN9 (1 × 10−4 CFU/mL) and 20 ppm Inhibitor I0.098 ± 0.002

1.21

42

6

System V:

400 mL in sterile CTW consist of 1% of NB with EN9 (1 × 10−4 CFU/mL) and 20 ppm Inhibitor II0.051 ± 0.008

0.63

75

2.5 Electrochemistry study

Electrochemical studies were conducted as our earlier methodology adopted from the (Narenkumar et al., 2017) using three-electrode system (CH Instrument Inc., USA model CHI 608E). The metal sample as working electrode saturated kangon and platinum sheet was used as reference and counter electrode. Tafel polarization were performed as per the (Rajasekar and Ting, 2011).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Anti-microbial activity and biofilm assay

The anti-bacterial properties of the extract of C. roseus and L. inermis on against the Bacillus oleronius EN 9 was measured by diameter of inhibition zone (DIZ). While increasing concentrations of plant extract showed the higher antimicrobial activity with the increasing DIA as 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1, 1.2, and 1.3 cm for C. roseus and 1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, 1.7 and 1.8 for L. inermis of concentrations 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 ppm, respectively. It indicated the extract of the both plants have the dose-dependent activity of the antibacterial. It reveals that L. inermis compared to the C. roseus highest inhibition efficiency was observed. The 20 ppm was identified as optimum inhibitory concentration against EN9 by crude extract of L. inermis and further this concentration was used for biofilm assay and biocorrosion experiments. Microtiter plate assay showed that EN9 was ability to form a biofilm on MS surfaces. Conversely, in existence of L. inermis, significant biofilm reduction was observed. This result reveals that L. inermis inhibits the biofilm of EN9 efficiency.

3.2 Biocorrosion studies

3.2.1 Weight loss method

The weight loss and the corrosion rate of each biocorrosion system were presented in Table 1. The WL of 0.175 g for system I, indicated that biocorrosion was accelerated by strain EN9. WL of control system II–V were found to be 0.087, 0.041, 0.021, 0.098, and 0.051 g, respectively. In abiotic system was about 1.07 mm/y, whereas experimental system I, II, III, IV, with bacteria and inhibitor showed the corrosion rate was 2.1 mm/y, 0.63 mm/y, 0.26 mm/y, 1.21 mm/y and 0.63 mm/y respectively. As seen from Table 1, in presence of inhibitor II the CR was radically decreased with a 0.26 mm/y and 0.63 mm/y when compared to others and efficiency of 75%. It reveals that inhibitor II as potent corrosion inhibitor efficiency when compared to inhibitor I and alone system.

3.2.2 Surface analysis

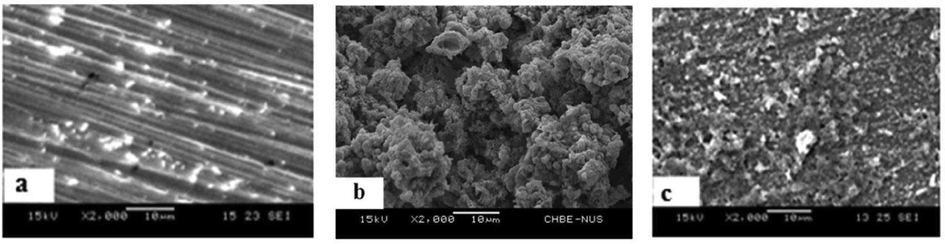

After the biocorrosion studies, the MS1010 coupon was removed from the experimental and control system, Biotic system and Inhibitor II systems were subjected to SEM analysis and were shown in Fig. 1, In Fig. 1b, thick biofilm was observed on surface of the metals compared to control (Fig. 1a) and V system (Fig. 1c). This confirms the EN9 biofilms are the ability to form dynamic structural and porous with erratically spread, which leads to cells adhere, grow, and form micro-colonies on a metal surface, which result to the development of inhomogeneous biofilm and thus accelerate the corrosion reaction susceptibility (Narenkumar et al., 2017).

SEM image of mild steel in various biocorrosion systems in presence/absence of bacteria/inhibitor a) Abiotic b) Biotic c) Inhibitor II with bacteria.

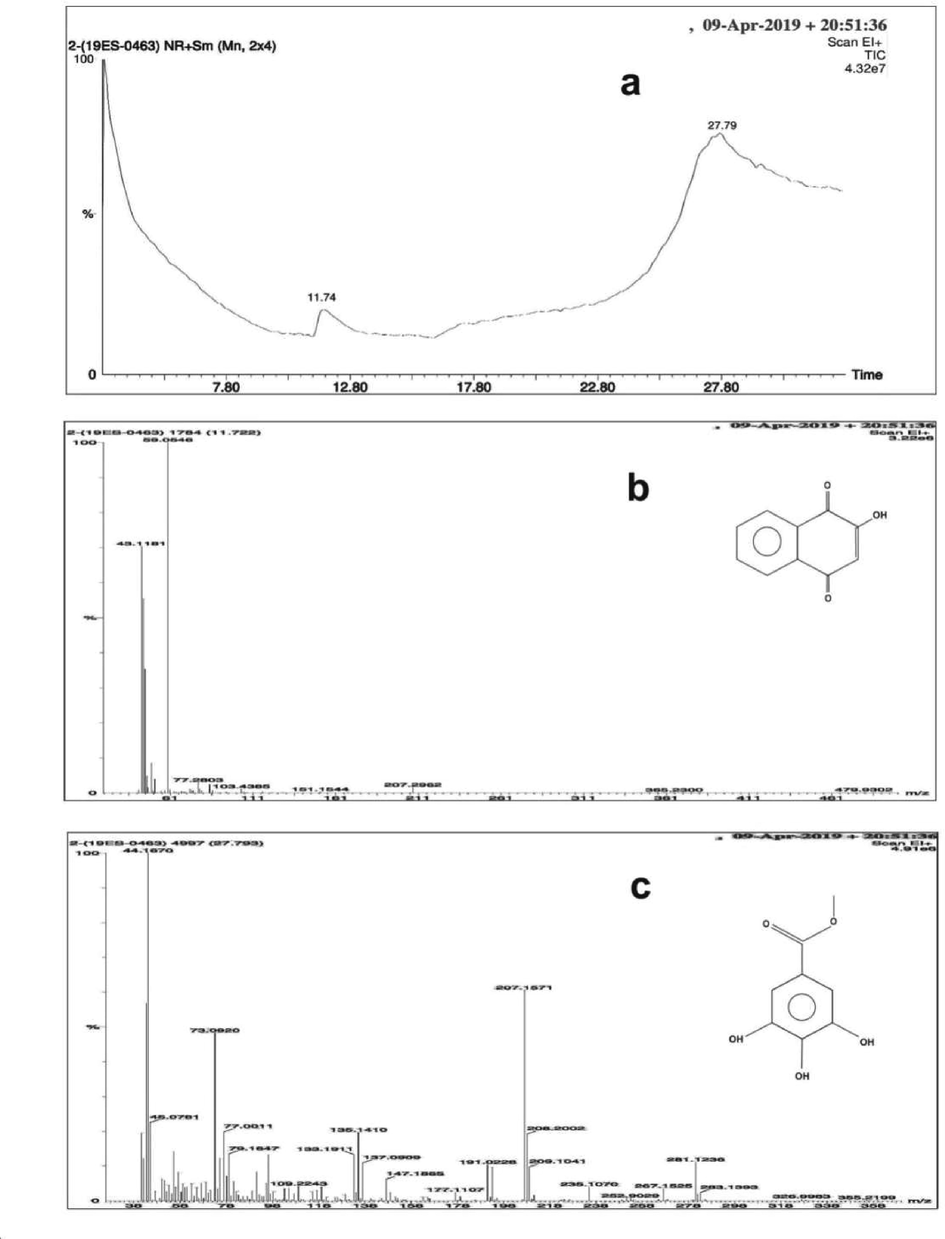

GC retention data of crude extract of L. inermis based on spectrum were presented in Fig. 2. Fig. 2 reveals that the crude extract of L. inermis consists of lawsone (2-Hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone, C10H6O3) and tannic among glucose and methyl gallate groups (El-Etre et al., 2005). It’s observed that L. inermis adsorbed on the metal surface acted as a protective film and thus inhibits the biofilm as a result CR was highly reduced.

Representative GCMS-chromatogram and corresponding mass spectrum of henna extract a) chromatogram b) lawsone c) methyl gallate.

3.2.3 Electrochemical studies

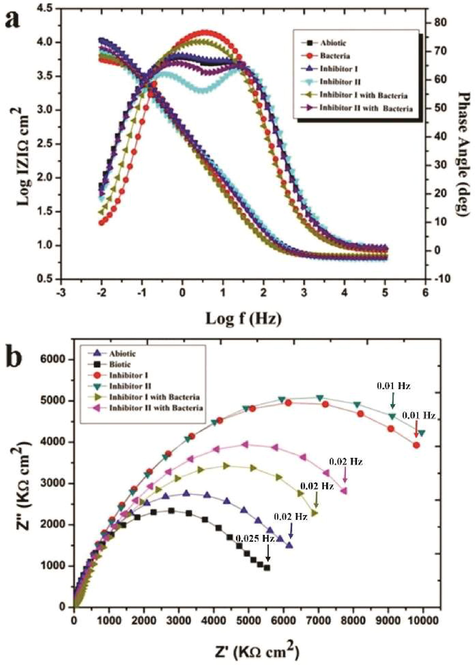

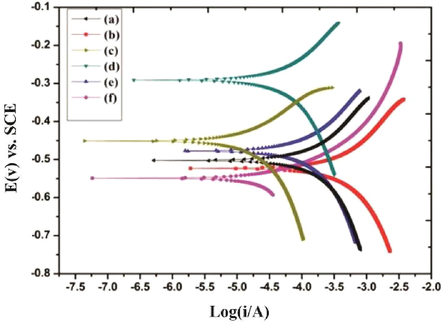

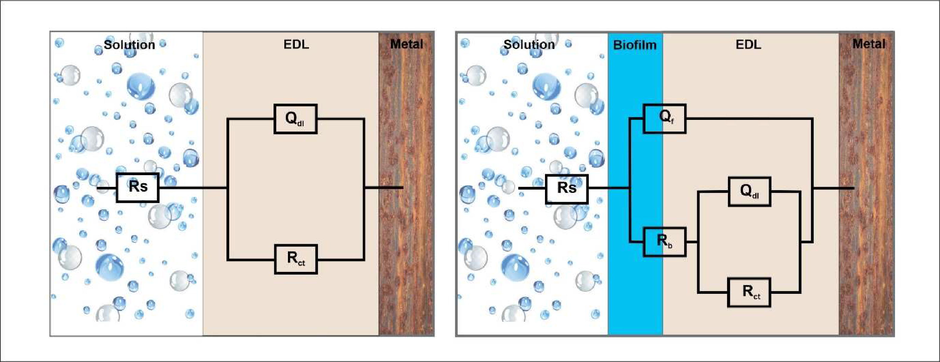

The data for the electrochemical analysis was presented in Tables 2 & 3 and Figs. 3 and 4 respectively. Two equivalent circuits used for fitting the EIS data such as R(QR) and R(Q(R(QR))) respectively (Fig. 5). The impedance plot in the presence of bacteria were exhibited de-pressed semicircle at high frequency region (Fig. 3) when compared to abiotic system due to the inhomogeneity and roughness of the metal surface (Guo et al., 2015). In addition, inhibitor II superior semicircles were observed which might to the inhibitor forms the barrier layer on the surface and thus inhibits the electron transfer from the metal surface. From the polarization resistance (Rp) of biotic system was 2-fold (5470 Ω cm2) higher than the inhibitor system (352.6 Ω cm2) at end of the incubation period, which indicate the acceleration of corrosion tendency by EN9. The system III and V Charge transfer resistance (Rct) and solution resistance (Rs) were observed as 8493 Ωcm2 and 6.381Ωcm2 (III) and 9905 Ωcm2 and 6.538 Ωcm2 (V) respectively. Inhibitor II showed the higher Rct and solution resistance (Rs) when compared to other systems (86.19 Ωcm2 and 6.894Ωcm2), it is inferred that formation of a passive layer on MS surface (Yuan et al., 2008). Tafel polarization curve of MS after biocorrosion studies were shown in Fig. 4. In control system, the cathodic peak was shifted to lower potential and which resulted the increasing cathodic current (1.3 × 10−4 A/cm2) (Conway and Jerkiewicz, 1994)(Narenkumar et al., 2016). Increasing icorr due to formation of biofilm, which resulted enhanced biocorrosion process (Al-Abbas et al., 2013). But in presence of inhibitor II (system III with inhibitor II and system V with EN9 with inhibitor II) icorr was higher reduced around 4.4 × 10−6 A/cm2 and 3.6 × 10−6 A/cm2 suggested that cured extract of L. inermis formed a thick film on surface and reduces the corrosion. It can be indicated that adsorption of inhibitor organo-metallic components and thus reduces the icorr values (Rajasekar et al., 2017; Parthipan et al., 2021). The EN9 adsorbed into the film which creates an electrostatic field across the film/solution interface. The film begins to enter the metal and initiates the pitting type of corrosion (Narenkumar et al., 2017). In inhibitor II, the potential shifts in a positive side. L. inermis extract adsorbed as film and prevent the aggressive corrosive ions and bacterial metabolites during biocorrosion process (Ostovari et al., 2009). Rs – Solution resistance, Qf – capacitance of biofilm, Rb – biofilm resistance, Qdl – capacitance of electric double layer, Rct – Charge transfer resistance. Rs – Solution resistance, Rct – Charge transferred resistance, Ecorr – Corrosion potential, icorr – corrosion current, ba – anodic slope, bc – Cathodic slope. Ƞ – Inhibition efficiency.

Day

Rs (Ω cm2)

Qf (10−4Ω−1Sncm−2)

Rb (Ω cm2)

Qdl (Ω−1Sncm−2)

Rct (Ω cm2)

Σχ2

Abiotic

6.555

–

–

3.935E-5

1429

1.89 × 10−3

Biotic

6.894

3.423E-5

5470

3.011E-6

86.19

2.4 × 10−4

Inh-I

6.872

2.791E-5

642.4

1.279E-5

4221

1.2 × 10−4

Inh-II

6.381

2.204E-5

344.3

3.718E-5

8493

4. 2.3 × 10−4

Inh-I & Bacteria

6.908

3.647E-5

8.855

7.752E-5

6808

2.2 × 10−4

Inh-II & Bacteria

6.538

2.544E-5

352.6

2.509E-5

9905

1.8 × 10−3

S.No

System

Polarization data

Ecorr (mV)

icorr (A/cm2)

ba (mV/decade)

bc (mV/decade)

ƞ (%)

1

Control

−522

6.2 × 10−5

6.2

3.3

–

2

System I

−536

4.3 × 10−4

5.9

4.6

–

3

System II

−485

5.2 × 10−4

5.1

4.2

26

4

System III

−312

4.4 × 10−6

5.4

4.1

39

5

System IV

−498

2.3 × 10−4

6.2

3.5

46

6

System V

−544

3.6 × 10−6

4.6

3.5

79

Bode and Nyquist for mild steel in biocorrosion systems in presence/absence of bacteria/inhibitor a) Bode b) Nyquist.

Polarization plot of mild steel in various biocorrosion systems in presence/absence of bacteria/inhibitor a) Abiotic, b) Biotic c) Inhibitor I d) Inhibitor II e) Inhibitor I with bacteria f) Inhibitor II with bacteria.

3.2.4 Proposed mechanism of corrosion inhibition of MS 1010 by cured extraction L. inermis

Most of the extract of L. inermis are based on hydroxy aromatic compounds includes tannin, gallic acid, and lawsone (Fig. 2). (El-Etre et al., 2005) reported, tannin has the ability to form a passive layer on the metal surface and thus inhibit corrosion. Insoluble complex compounds were formed due to the lawsone molecules on the surfaces with the binding of metal cations which was confirmed by GCMS. Since the inhibitor has predominant groups lawsone adhesion on the metal surface and reduced cathodic and anodic reaction. Cured extract of L. inermis contains has aromatic compounds includes cyclic delocalized π electron, especially a benzene ring (Lide, 2004). The π electrons of the benzene ring decrease the evolution of hydrogen and a pair of electrons on the hydroxyl group was decreased the anodic dissolution (Quraishi and Sardar, 2003; Raja et al., 2013). This phenomenon was illustrated as schematic diagram in Fig. 6.

Two physical models and the corresponding equivalent circuits used for fitting the impedance spectra of mild steel: (a) abiotic system, and (b) biotic system.

Schematic diagram of corrosion inhibition by crude extract of Lawsonia inermis in re-circulating system.

4 Conclusions

In this present study, the chosen cured plant extract act as an efficient, eco-friendly, and natural corrosion inhibitor for biocorrosion of MS 1010 in a re-circulating water system. Green corrosion inhibitor of L. inermis was identified as a potential biocide and corrosion inhibitor for MS surface and inhibition efficiency of 75% at 20 ppm. SEM analysis confirmed the green corrosion inhibitor was adsorbed onto the surface, complex with iron and formed a passive layer which resulted the reduction of CR this result support too EIS. The green corrosion inhibitor is promising compounds that inhibit the biocorrosion of MS in a re-circulating water system. Further, the pilot-scale studies on the dosage and will be explained further studies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jayaraman Narenkumar: Writing - original draft. Azhagesan Ananthaselvam: Methodology. Mohamad S. Alsalhi: Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing. Sandhanasamy Devanesan: Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Abudukeremu Kadier: Validation, Writing - review & editing. Maruthamuthu Murali Kannan: Formal analysis, Validation, writing - review & editing. Aruliah Rajasekar: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP-2021/68), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Microbial corrosion in linepipe steel under the influence of a sulfate-reducing consortium isolated from an oil field. J. Mater. Eng. Perform.. 2013;22:3517-3529.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pimpinella anisum seeds: antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity on human neonatal skin stromal cells and colon cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomedicine.. 2016;11:4439.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of Cooling Water. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2009.

- Green inhibitors for corrosion protection in acidizing oilfield environment. J. Ass. Arab Uni. Basic App. Sci. 2016

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical modeling and experimental studies of Terebinth extracts as green corrosion inhibitor for iron in 3% NaCl medium. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci.. 2020;32(7):2995-3004.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemistry and Materials Science of Cathodic Hydrogen Absorption and Adsorption. Pennington, NJ: The Electrochemical Society; 1994.

- Corrosion behaviour of metal complexes of antipyrine based azo dye ligand for soft-cast steel in 1 M hydrochloric acid. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci.. 2020;32(1):881-890.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion inhibition of some metals using lawsonia extract. Corros. Sci.. 2005;47:385-395.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbial corrosion inhibition of mild steel in salty water environment. Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2009;11:156-159.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biocidal Control of Metals and Corrosion. InIst Pan-American Congress on Corrosion and Protection (AAC-NACE). Argentina: Mar del Plata; 1992. p. :371-378.

- Experimental and theoretical studies of benzalkonium chloride as an inhibitor for carbon steel corrosion in sulfuric acid. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2015;24:174-180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion of carbon steel by sulphate reducing bacteria: Initial attachment and the role of ferrous ions. Corros. Sci.. 2005;93:48-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibiting sulfate-reducing bacteria in biofilms on steel with antimicrobial peptides generated in situ. Appl. Microbiol. Biot.. 1999;52:267-275.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green inhibitors for corrosion of metals: a review. Chem. Sci. Rev. Lett.. 2012;1:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lalpuria, M., Karwa, R., Anantheswaran, R.C., Floros, J.C., 2013. Modified agar diffusion bioassay for better quantification of N isaplin®. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114 663-71. .

- McIntyre, P.J., Mercer, A.D., 2010. Corrosion testing and determination of corrosion rates. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/corrosion-monitoring.

- Role of bacterial plasmid on biofilm formation and its influence on corrosion of engineering materials. J. Bio-and Tribo-Corros.. 2016;2:24.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Narenkumar, J., Parthipan, P., 2017. AU. Nanthini, G. Benelli, K. Murugan, A. Rajasekar, Ginger extract as green biocide to control microbial corrosion of mild steel. 3 Biotech 7; 1-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28593517.

- Narenkumar, J., Ramesh, N., Rajasekar, A., 2018.Control of corrosive bacterial community by bronopol in industrial water system. 3 Biotech, 8 55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29354366.

- Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in 1 M HCl solution by henna extract: a comparative study of the inhibition by henna and its constituents (Lawsone, Gallic acid, α-d-Glucose and Tannic acid) Corros. Sci.. 2009;5:1935-1949.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbiologically-influenced corrosion of orthodontic alloys: a review of proposed mechanisms and effects. Aust. Orthod. J.. 2009;25:63-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glycyrrhiza glabra extract as an eco-friendly inhibitor for microbiologically influenced corrosion of API 5LX carbon steel in oil well produced water environments. J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;333:115952

- [Google Scholar]

- Allium sativum (garlic extract) as a green corrosion inhibitor with biocidal properties for the control of MIC in carbon steel and stainless steel in oilfield environments. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad.. 2008;132:66-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, J.C., Coelho, M.V., GóesFilho, J.T., Menezes. M.A., 2005. Control of sulphate reducing bacteria through the application of sodium molybdate. 2nd Mercosur Congress on Chemical Engineering, Brazil.

- Hector bases-A new class of heterocyclic corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acid solutions. J. Appl. Electrochem.. 2003;33:1163-1168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of green corrosion inhibition by alkaloid extracts of Ochrosia oppositifolia and isoreserpiline against mild steel in 1 M HCl medium. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2013;7;52(31):10582-10593.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitive effect of black pepper extract on the sulphuric acid corrosion of mild steel. Mat Lett. 2008;62:2977-2979.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekar, A., Ting, Y.P., 2010. Microbial corrosion of aluminum 2024 aeronautical alloy by hydrocarbon degrading bacteria Bacillus cereus ACE4 and Serratiamarcescens ACE2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 49 6054-61. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ie100078u.

- Role of inorganic and organic medium in the corrosion behavior of Bacillus megaterium and Pseudomonas sp. in stainless steel SS 304. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2011;50:12534-12541.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of corrosive bacterial consortia isolated from water in a cooling tower. International Scholarly Research Notices 2014

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Airborne bacteria associated with corrosion of mild steel 1010 and aluminum alloy 1100. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2017;24:8120-8136.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of corrosive bacterial consortia isolated from water in a cooling tower. Int. Scholarly Res. Notices. 2014;2014:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in 1 M HCl by sweet melon peel extract. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci.. 2019;31(4):1344-1351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbial community structures and in situ sulfate-reducing and sulfur-oxidizing activities in biofilms developed on mortar specimens in a corroded sewer system. Water Res.. 2009;43:4729-4739.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neem extract as an inhibitor for biocorrosion influenced by sulfate reducing bacteria: a preliminary investigation. Eng. Fail. Anal.. 2014;36:92-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) in industrial equipment failures. Eng. Fail. Anal.. 2007;14:1500-1511.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azadirachta indica leaves extract as inhibitor for microbial corrosion of copper by Arthrobacter sulfureus in neutral pH conditions—a remedy to blue green water problem. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E. 2016;64:269-278.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanistic modeling of biocorrosion caused by biofilms of sulfate reducing bacteria and acid producing bacteria. Bioelectrochemistry. 2016;110:52-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of erosion-corrosion of aluminium alloy composites: Influence of slurry composition and speed in a different mediums. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci.. 2019;31(4):674-683.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biocorrosion behavior of titanium oxide/butoxide-coated stainless steel. J. Electrochem. Soc.. 2008;155:C196.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]