Translate this page into:

Eco-friendly management of wheat stripe rust through application of Bacillus subtilis in combination with plant defense activators

⁎Corresponding author. arslan.khan@mnsuam.edu.pk (Muhammad Arslan Khan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Stripe rust (SR) caused by Puccinia striiformis Westend. f. sp. tritici Erikss (Pst) is one of the most important and destructive disease of wheat worldwide. In Pakistan, stipe rust appeared as epidemic and is causing huge losses to wheat production. However, wheat breeding programs are not sufficiently advanced to cope with the recently emerged Puccinia striiformis strains. Under this scenario, current research was carried out for safe, effective and sustainable management of stripe rust of wheat. Seven wheat varieties include Sehar-06, Galaxy-13, Abdul Sattar-02, Faisalabad-08, Johar-16, TD-1 and Ujala-16 were planted at research farm of Muhammad Nawaz Shareef University of Agriculture, Multan, Pakistan during November 2019–20 and 2020–21 to determine their response toward Puccinia striiformis. The fungicide Tilt®, propiconazole, (T2) at the rate of 3 mL per 1500 mL water was used while the Bacillus subtilis (T1) was added at rate of 0.25 mL/1500 mL water with 15 g of dextrose, 0.25 g of chitosan and 0.25 g of salicylic acid in 1500 mL water to make a fine suspension. Our results showed that T1 reduced the disease effectively up to (8.18%) followed by T2 (10.7%) as compared to T0 (23.8%). The correlation between minimum air temperature, relative humidity and disease severity was highly significant while with maximum air temperature it was negatively non-significant. Also, wind speed, solar radiation and rainfall showed non-significant correlation with disease severity. After treatment, application of T1 and T2, minimum air temperature expressed a significant correlation with disease severity on varieties Sehar-2006, Galaxy-13 and Abdul Sattar-02 while non-significant correlation with disease severity on varieties Faisalabad-08, Johar-16, TD-1 and Ujala-16. Similarly, maximum air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and solar radiation showed non-significant correlation with disease severity while rain fall was negatively non-significant. The current study showed that Bacillus subtilis is an ecofriendly management of stripe rust and its combination with plant defense activators enhance the efficacy and suppress disease. This management strategy is an innovative, and the results obtained will be helpful for better, ecofriendly and effective management of disease.

Keywords

Bacteria

Varietal resistance

Biological Control

Rust

Wheat

1 Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) belongs to the family Poaceae and the genus Triticum. It’s one of the important food crops for an individual that has been eaten all over the world (Weiss and Zohary, 2011). It began to spread out from the Mediterranean Basin into eastern and western Europe between 4000 and 3500 BCE (Bonjean, 2016a, b) and is the first-ever cultivated crop that plays a vital role in Pakistan's food economy (Raza et al., 2019). Pakistan is the 7th largest wheat-growing country in the world and wheat production enhanced from 7,294 thousand tonnes in 1970 to 24,300 thousand tonnes in 2019, rising at an annual average rate of 2.83%. Wheat has significant nutritional value as it provides about 78.10% of carbohydrates, 14.70% of protein, 2.10% of fat, 2.10% of minerals, vitamin B complex, zinc, iron, selenium, and magnesium (Topping, 2007; Shewry and Hey, 2015).

Various factors like climatic factors, pests, and diseases are involved in the reduction of wheat yield (Singh et al., 2016a). Among them, wheat rust is the world's most critical disease (Dean et al., 2012). Stripe rust (SR), also known as yellow rust is a disease that affects wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and is caused by the bio tropic fungus Puccinia striiformis Westend. f. sp. tritici Erikss (Pst) (Chen et al., 2014). SR is a disease that causes severe losses to wheat production in cold climates and moist weather zones, especially major wheat-producing countries like Australia, France, Canada, India, China and United States (Ali et al., 2017) and now severely damaging the wheat growing in Pakistan. There are various management strategies to control rust disease like resistant cultivars, fungicide application and biological control. The selection of a plant variety that has resistance or tolerance to disease makes it possible to avoid or lessen the use of pesticides (Gebhardt and Valkonen, 2001). It’s important to discover certain cultivars that have resistance for SR but it may not be feasible to find resistant varieties to all pathogen strains in a specific area, so it is important to identify the pathogen strains that are the most damaging in an area and find suitable resistant source (Pedley and Martin, 2003). On the contrary, pesticides and fertilizers usage is polluting the environment and it’s also believed that pesticides induce cancer in human beings (Islam et al., 2015; Thongprakaisang et al., 2013).

Currently, the key reality is that the entire agriculture sector is being shifted towards biological control strategy for the management of plant diseases in developed as well as developing countries. Biological control agents induce systemic resistance that strengthens the mechanical and physical vigor of the cell wall and alters the host biochemical and physiological activities (Naeem et al., 2015). Bio-inoculants help in lowering the disease by using various mechanisms like the development of siderophores; secondary antimicrobial metabolites and lytic enzyme secretion (Keswani et al., 2014). Bio-controls promote plant growth by developing fluorescent siderophores bonded to a central molecular iron in the area of rhizosphere, rendering it less approachable for other challenging microorganisms (Singh et al., 2014). Keeping in view the economic importance of SR, lethal impact of pesticides on ecosystem and unavailability of resistant source against SR; the current study was planned to minimize the losses caused by SR through the identification of suitable resistant varieties and the role of environmental factor’s in SR development. The use of a new biological control formulation and its combination with plant defense activators for the management of SR is an innovative approach in the current study.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Screening trial

The seven wheat varieties i.e. Sehar-06, Abdul Sattar-02, Ujala-16, Galaxy-13, Faislabad-2008, TD-1 and Johar-16 were collected from Punjab Seed Corporation. Screening trial, with three replications of each variety, was conducted to check the relationship between disease and environmental factors like maximum air temperature, minimum air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and rainfall.

2.2 Disease management trial

Two trials were conducted at MNSUAM, Multan on loamy soil during growing seasons 2019–20 and 2020–21 from November to April. The disease appeared naturally in both trials and disease severity data was recorded by data chart (Line and Qayoum, 1992). The two independent trials were conducted using the seven wheat cultivars Sehar-06, Abdul Sattar-02, Ujala-16, Galaxy-13, Faislabad-08, TD-1 and Johar-16. The experimental set-up was a completely randomized block design with 3 replication, control (C), biological (B), fungicide (F), and there was 5 rows of each replications of each variety. A plot size of 2722.51 ft2 (35 ft length and 65 ft width) and with 6 ft space between the plots. Plots were sown with a plot sowing machine at 2–4 cm depth aiming at 400 seeds per m2. Chemical control was done using Tilt® (Propiconazole) fungicide by adding 3 mL fungicide in 1500 mL of water to prepare a fine suspension and mixed properly. The purpose was to check the comparison between biological control agent and fungicide in 2019–20 and 2020–21 respectively. Bio-control agent used was B. subtilis. The nutrient media was prepared and autoclaved for 15 min at 121 °C at 15PSI. After inoculation it was kept at 37 °C and later harvested manually. The culture was kept in distilled water at 4 °C after harvesting. For the suspension bacterial strain was added @ 0.25 mL/1500 mL water having 15 g of dextrose, 0.25 g of chitosan and 0.25 g of salicylic acid in 1500 mL water to make a fine suspension. Wheat crop was sprayed 4 times, first sprayed at time of disease appearance then after 12 days, 10 days and 9 days and data was recorded on regular basis. The products were applied with a self-propelled sprayer operating at a speed of 4.5 Km/h and height of 40 cm using Teejet 9504 nozzle. Disease assessment was carried out visually as percentage of yellow rust coverage of green leaves evaluated at specific leaf layers at intervals of ten days.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Data of stripe rust as influenced by the treatment was statistically analyzed, analysis of variance of all treatments was determined through ANOVA technique using the software Statistix 8.1 and treatments were compared with LSD test at 5% level of probability. The Pearson's correlation of environmental data and disease was analyzed through SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM SPSS Inc.) software.

3 Results

3.1 Field trial

3.1.1 Screening and disease severity (%) of wheat varieties

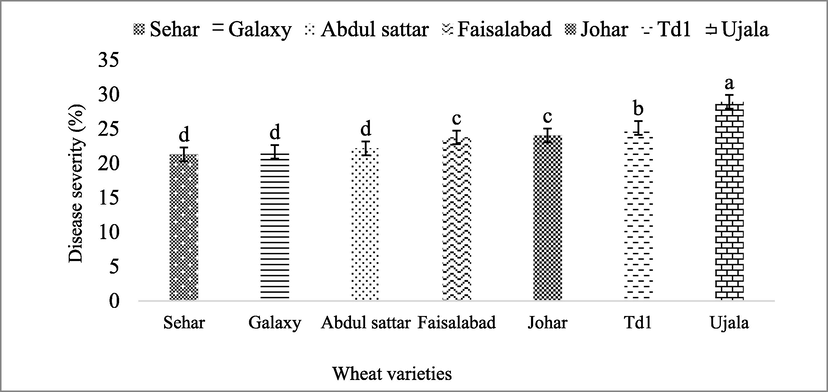

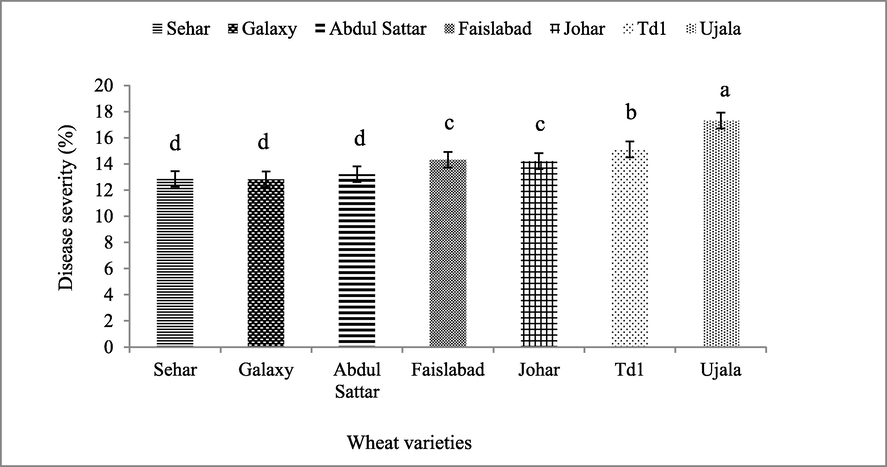

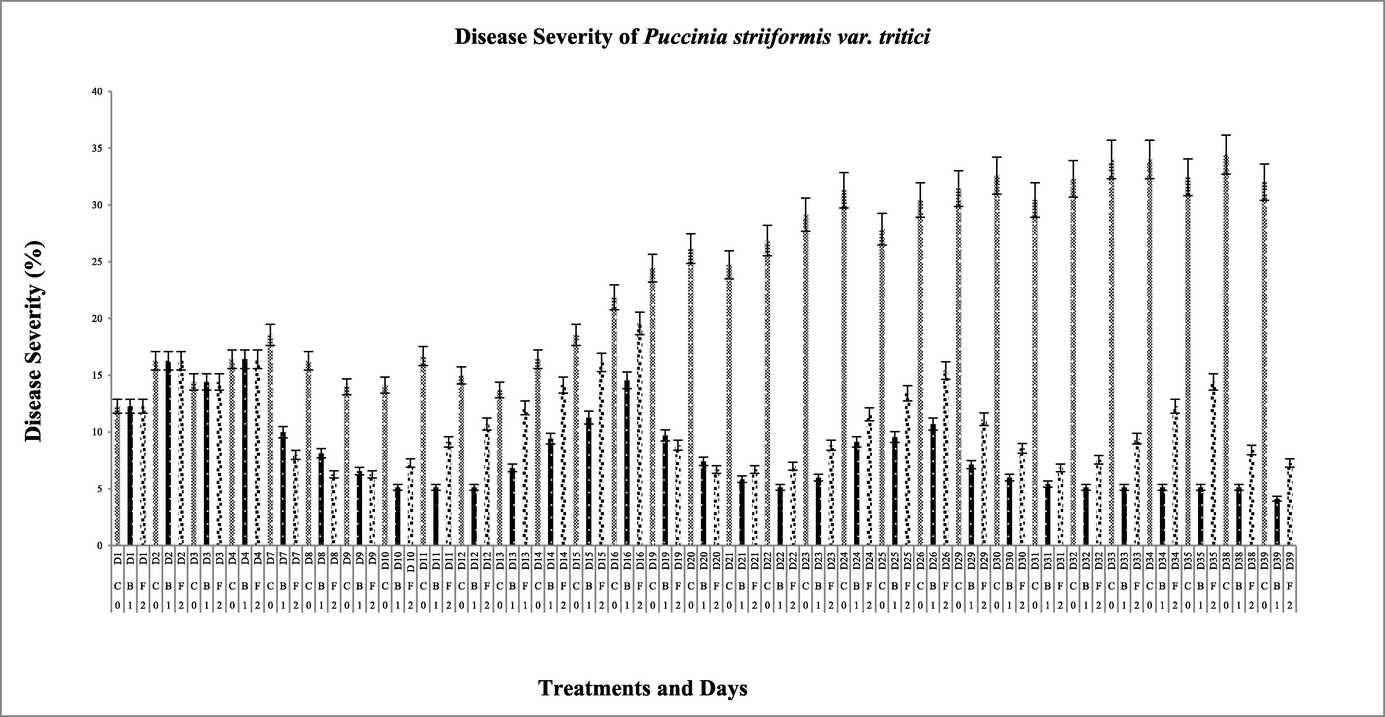

Seven wheat varieties (i.e. Sehar-06, Galaxy-13, Abdul Sattar-02, Faisalabad-08, Johar-16, TD-1 and Ujala-16) were screened against stripe rust. The overall seasonal data showed that maximum disease was observed in Ujala-16 followed by TD-1, Johar-16, Faisalabad-08, Abdul Sattar-02, Galaxy-13 and Sehar-06 (Fig. 1). The average disease severity percentage calculated in different varieties before and after application of treatments was noted 17.3%, 15.1%, 14.3%, 14.2%, 13.2%, 12.8% and 12.8% in Ujala-16, TD-1, Faisalabad-08, Johar-16, Abdul Sattar-02, Sehar-06 and Galaxy-13 respectively as shown in (Fig. 2).

The response of wheat varieties against yellow rust in open field screening trial. The disease severity (%) data of yellow rust without any treatment. Bars are standard errors of mean. The lettering on bars indicate the mean difference at 5%.

The average seasonal disease severity (%) of wheat varieties. The data taken before and after treatments at various time intervals. Bars are standard errors of mean. The lettering on bars indicate the mean difference at 5%.

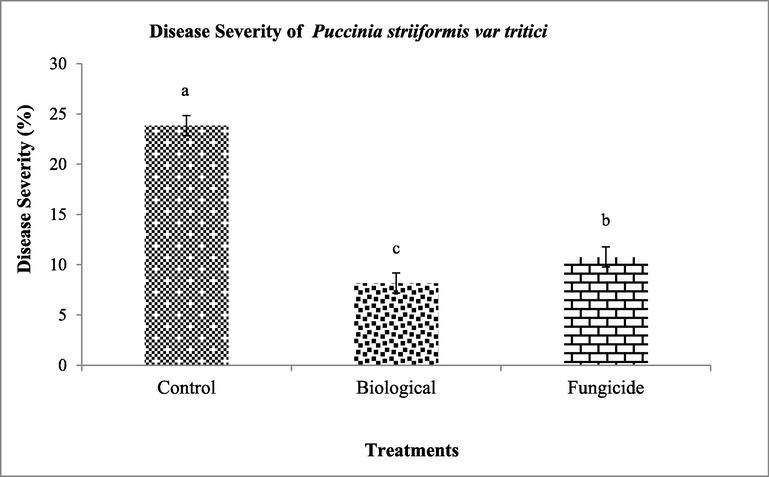

3.1.2 Overall efficacy of biological and chemical treatments

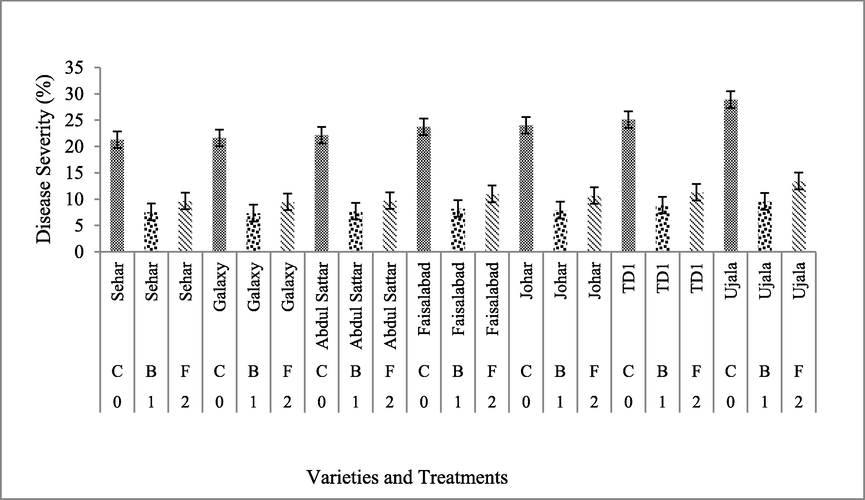

The results showed that biological control agent expressed maximum suppression in disease severity as compared to fungicide. In variety Ujala-16, the biological (B) treatment showed 9.58% severity as compared to fungicide (F), 13.4%, and control (28.9%). In variety Galaxy-13, the control showed 21.6% disease severity whereas the biological control treatment expressed 7.35% severity as compared to fungicide that was 9.48%. Similarly, the disease suppression of Sehar-06 was (7.58%) in biological control agent while fungicide application showed (9.66%) and with no application of biological and fungicide disease severity was (21.29%).

Abdul Sattar-02 had (7.74%) disease severity followed by application of biological agent while with application of fungicide Abdul Sattar-02 expressed (9.74%) disease severity as compared to control (24.7%). Variety Johar-16 showed disease severity of (7.93%) with the application of biological control agent and with application of fungicide the disease severity was (10.6%) as compared to control (25.1%). Faisalabad-08 had disease severity of (8.22%) in application of biological control agent while with application of fungicide disease severity was (11%) as compared to control (23.7%). In TD-1, with the application of a biological agent disease severity was (8.87%) and with the application of fungicide disease severity was (11.3%) while in control disease severity was (25.1%).

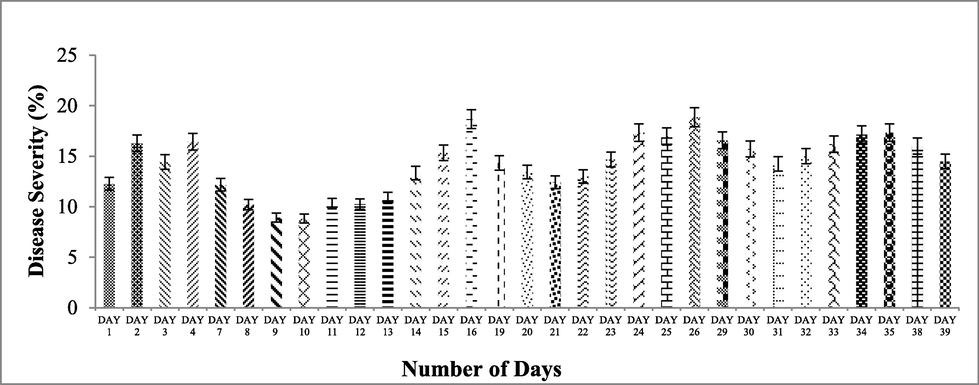

Ujala-16 had disease severity of (9.58%) with the application of biological control agent while with the application of fungicide disease severity was (13.45%) as the control, showed disease severity of, 28.9%, (Fig. 3). The biological control agent results were more efficient than the chemical. Interaction between days and disease severity (%) indicated the overall severity (%) of wheat varieties. At the day first with no application of any treatment the overall disease severity was (12.2%) and very next day it was increased to (16.2%). On day three and four disease severity was 14.4% and 16.4% respectively. The application of biological control agent and fungicide was done on day four after disease appearance and data was noted on day seven, after 3 days of application.

Efficacy of biological control and chemical control against wheat yellow rust (Varieties × Treatments) *(C = control; B = biological; F = fungicide).

On day seven disease severity was noted at 12.1%. Disease severity on day eight, nine, ten, and eleven was at 10.2%, 8.95%, 8.85%, and 10.3% respectively. Disease severity on day thirteen was 10.9% and on day fourteen disease severity increased to 13.3% and raised up to 18.6% on day sixteen. After the second spray, at day 16, of biological control agent and fungicide the disease severity was calculated 14.3% on day nineteenth, after 3 days of application. On day twenty and twenty one the disease severity was 13.4% and 12.4% respectively. On day twenty two disease severity was 13% whereas on day twenty third it was noted, 14.6%. On day twenty four disease severity increase up to 17.3%. On day twenty five disease severity was 17.9% and on day twenty six disease severity was 18.8%. After third application of biological control agent and fungicide, on day twenty six, results showed clear reduction of disease severity at day twenty nine (16.5%), thirty (15.7%) and thirty one (14.2%). After thirty two days the disease severity started increasing and reached upto 17.14% on the day thirty four. The fourth application was done at thirty fifth day. Data showed that the disease severity was reduced to 14.4% (Fig. 3).

3.1.3 Response of treatments into days

Interaction between treatments and days expressed that at day one, two, three and four the treatments i.e., biological, fungicide and control, had disease severity of 12.2%, 16.2%, 14.4% and 16.4% respectively. The application on day four of biological control agent and fungicide reduced the severity up to 10% and 8% respectively on day seven as compared to control (18.5%). On day eight in biological treatment the disease severity was noted 8.14% while in fungicide 6.28% as compared to control (16.2%). On day nine disease severity of biological was 6.57% while disease severity in fungicide application recorded same as previous (6.28%) as compared to control (14%).

On day ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen, fourteen and fifteen disease severity of biological control agent was (5.14%, 5.14%, 5.14%, 6.85%, 9.42% and 11.28%) respectively while fungicide treatments had disease severity of (7.28%, 9.14%, 10.7%, 10.7%, 14.1% and 16.1%) respectively as compared to control (14.1%, 16.7%, 15%, 13.7%, 16.4% and 18.5%) respectively. On day sixteen disease severity of biological was calculated (14.5%) and in fungicide (19.5%) as compared to control (21.8%). On day nineteen after application of biological control agent and fungicide the disease severity of biological control agent was (9.71%) while fungicide had disease severity of (8.85%) as compared to control (24.4%). On day twenty and twenty one disease severity of biological control agent was (7.42% and 5.85%) respectively while fungicide had disease severity of (6.71% and 6.71%) respectively as compared to control (26.1% and 24.7%) respectively.

On day twenty two, twenty three, twenty four and twenty five biological control application showed disease severity of (5.14%, 6%, 9.14% and 9.57%) respectively while fungicide had (7%, 8.85%, 11.5% and 13.4%) respectively as compared to control (26.8%, 29.1%, 31.2% and 27.8%) respectively. On day twenty six the disease severity of biological treatment was (10.7%) while disease severity of fungicide was (15.4%) as compared to control (30.4%) while on day twenty six third spray of biological control agent and fungicide was applied. On day twenty nine disease severity of biological control agent was (7.14%) while disease severity of fungicide was (11.1%) as compared to control (31.4%). On day thirty disease severity of biological treatment was (6%) and fungicide had disease severity of (8.57%) as compared to control (32.5%) while on day thirty one the disease severity of biological control agent was (5.42%) while disease severity of fungicide was (6.85%) as compared to control (30.4%).

On day thirty two, thirty three and thirty four biological had disease severity of (5.14%, 5.14% and 5.14%) respectively while fungicide had disease severity of (7.57%, 9.42% and 12.2%) respectively as compared to control (32.2%, 34% and 34%) respectively. After fourth spray disease severity of biological treatment was (5.14%) while fungicide had (8.42%) as compared to control (34.4%) on day thirty eight. On day thirty nine biological treatment had disease severity of (4.14%) while fungicide had a disease severity of (7.28%) as compared to control (32%) (Fig. 4, 5). The complete response of treatments in whole season indicated that biological treatment resulted maximum disease reduction of (8.18%) while fungicide showed (10.7%) disease reduction as compared to control (23.8%). Moreover, results indicated that the response of fungicide treatment was quick after the spray as compared to biological treatment, while with time passage the effect of fungicide treatment decreased as compared to biological treatment (Fig. 6).

Interaction of treatments and days showing disease severity (%) after application of biological control agent and fungicide. Bars are standard errors of mean.

Day wise data of disease severity (%) of wheat stripe rust (Treatments × Days) showing the efficacy of biological control agents as compared to fungicide and control. *(D = day; C = control; B = biological; F = fungicide). Bars are standard errors of mean.

Data of overall response of treatments in a cropping season showing the disease severity (%) of Puccinia striiformis var. tritici in biological treatment as compared to fungicide and control.

3.1.4 Correlation of disease development and environmental factors

Among environmental factors, minimum air temperature (r = 0.79) and relative humidity (r = 0.75) expressed highly significant correlation with disease severity whereas maximum air temperature was negatively non-significant with disease severity. Wind speed, solar radiation and rain fall was also non-significant with disease severity as shown in (Table 1). Due to application of treatments; the environmental factors i.e. minimum air temperature expressed significant correlation with disease severity of wheat variety Sehar-06, Galaxy-13 and Abdul Sattar-02 while non-significant with Faisalabad-08, Johar-16, TD-1 and Ujala-16. Maximum air temperature showed non-significant correlation with disease severity. Relative humidity, wind speed and solar radiation also showed non-significant correlation with disease severity while Rain fall was negatively non-significant in disease severity as shown in (Table 2).

Varieties

Max temprature

Min temprature

Humidity

Wind Speed

Solar radiation

Rain fall

Sehar-06

−0.117

0.2660.748**

0.0000.751**

0.0000.230

0.1070.155

0.2030.261

0.078

Galaxy-13

−0.082

0.3300.790**

0.0000.705**

0.0000.256

0.0750.161

0.1890.248

0.090

Abdul Sattar-02

−0.055

0.3840.769**

0.0000.707**

0.0000.231

0.1060.145

0.2180.231

0.106

Faisalabad-08

−0.118

0.2640.753**

0.0000.740**

0.0000.249

0.0890.141

0.2240.255

0.083

Johar-16

−0.099

0.2990.751**

0.0000.721**

0.0000.256

0.0820.136

0.2320.264

0.076

TD-1

−0.142

0.2240.705**

0.0000.746**

0.0000.232

0.1040.098

0.3010.237

0.100

Ujala-16

−0.059

0.377

0.671**

0.000

0.613**

0.000

0.179

0.167

0.191

0.1520.144

0.220

Varieties

Max temperature

Min temperature

Humidity

Wind Speed

Solar radiation

Rain fall

Sehar-06

−0.015

0.4430.199*

0.0280.168

0.0540.121

0.1240.041

0.348−0.086

0.206

Galaxy-13

0.026

0.4040.267**

0.0050.151

0.0750.154

0.070.064

0.271−0.092

0.19

Abdul Sattar-02

0.026

0.4020.221*

0.0170.14

0.090.125

0.1170.04

0.35−0.099

0.173

Faisalabad-08

−0.016

0.4410.148

0.0780.118

0.1310.112

0.1430.006

0.479−0.109

0.149

Johar-16

−0.01

0.460.166

0.0560.126

0.1150.132

0.1040.013

0.45−0.104

0.161

TD-1

−0.073

0.2420.027

0.3990.092

0.1910.093

0.186−0.036

0.364−0.115

0.136

Ujala-16

−0.074

0.242

−0.066

0.265

−0.025

0.407

0.071

0.248

−0.046

0.331−0.124

0.118

4 Discussion

Stripe rust (SR) commonly known as yellow rust cause yield losses ranging from 10 to 50% resulting low kernel weight and quality in wheat due to infection (Chen, 2005; Afzal et al., 2008; Huerta-Espino et al., 2011; Anteneh et al., 2013). This pathogen decreases photosynthetic rate in leaves by reducing the chlorophyll contents (Yahya et al., 2020). SR initiates early infection in wheat that results in a complete yield loss. However, it has been noted that the amount of losses varies between 10 and 70 percent depending on local weather factors, the emergence of new pathogen races, cultivar vulnerability, and early infection during crop season (Begum et al., 2014). Among various management methods that are being used to resolve rust diseases like resistant cultivars and fungicide application, the genetic regulation of rusts had substantial achievement in the region where pathotype survey is intimately combined with the pre-breeding activities aimed at rust resistance and the post-release of wheat cultivar management (Park et al., 2009).

Genetic resistance is considered the most effective and economic method of reducing rust losses (Liu and Kolmer, 1997). In the present study, screening results showed that the wheat variety Ujala-16 was more susceptible to SR. The minimum disease was noted on Sehar-06 and Galaxy-13 followed by Abdul Sattar-02, Johar-16, Faisalabad-08, and TD-1. The resistance against pathogens in wheat cultivars may be the more efficient, eco-friendly, and sustainable method for leaf and SR management. The research is in agreement with (Draz et al., 2015), with the conclusion that local studies on leaf rust including the response determination of commercially cultivated cultivars are of great benefit for wheat breeders. These results are also similar with the findings of (Liu and Kolmer, 1997; Singh et al., 1991; El-Daoudi et al., 1985; El-Daoudi et al., 1987; Herrera-Foessel et al., 2006; Kassem et al., 2011).

According to (Chen et al., 1995) and (Jørgensen et al., 2014) the application of fungicides for rust management is commonly used in many parts of the world for high productivity, and their efficacy partly depends on the degree of disease and crop stage (Viljanen-Rollinson et al., 2006). Unfortunately, the injudicious use of the chemical pesticides producing fatal environmental pollution because of their residual effects. Therefore, other alternative strategies for disease management should be given priority. In developed countries the agricultural sector is being shifted towards the effective and safe biological controls.

In current research, the biological control agent, Bacillus subtilis diluted in chitosan and salicylic acid was applied for the management of SR. The results showed the significant disease suppression in biological treatment over fungicide treatment. Similar study also revealed that evaluation of bacterial strain, B. subtilis, proved better than Trichoderma viride against P. triticina. There was significant increase in latent, incubation cycle of pathogen, kernel weight and yield (Omara et al., 2019). Previously done study reported that fungicides and bio agents like Pseudomonas fluorescence and Bacillus subtilis were effective in controlling SR (Singh et al., 2016b). In current study the application of Bacillus subtilis was done and the disease suppression was calculated 91.9% over fungicide 89.3% as compared to control (76.2%). The similar results were also calculated by different researchers (Selvakumar et al., 2014; Naeem et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; El-Kazzaz et al., 2020; Kiani et al., 2021; Ahamad, 2021).

In this study, chitosan and salicylic acid were also added with the bio-agent to check their efficacy against SR. The similar study was also done by (Hassan and Chang, 2017), the researcher assessed bio-agents efficacy against the growth of SR on wheat and checked the chitosan inhibition for growth and sporulation of pathogen, spore viability and germination, by disrupting their cell membrane. The results showed that combination of chitosan with B. subtilis reduced the disease upto 40–45%. The current research is also inline with (Hu et al., 2020; Feodorova-Fedotova et al., 2019; Pandey et al., 2018). The present study highlighted that combination of chitosan, salicylic acid and Bacillus subtillis proved effective against SR. The previous work showed the effect of salicylic acid on plant systemic acquired resistance (SAR). The scientist concluded that SAR or defensive priming is the result of systemic dissemination and the phyto-hormone salicylic acid is involved in SAR activation (Corredor-Moreno et al., 2021).

In the current study, the correlation of environmental factors with SR was determined on seven wheat varieties i.e. Sehar-06, Galaxy-13, Abdul Sattar-02, Faisalabad-08, Johar-16, TD-1 and Ujala-16. Results showed a highly significant correlation of relative humidity and minimum air temperature on all wheat varieties. The wind speed, solar radiation, rain fall were concluded to be non-significant. The similar responses of environmental factors with disease were related by workers (Singh et al., 2000; Riaz et al., 2013). The current study is also similar with the finding of different scientists (Brar et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2019; Naseri and Marefat, 2019; Hu et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Moreno et al., 2020; Naseri and Kazemi, 2020; Chen, 2020; Ali et al., 2021).

5 Conclusion

Stripe rust is a devastating disease of wheat. Bacillus subtilis, chitosan, and salicylic acid were proven to be an efficient and environmentally friendly way to treat stripe rust in the current study. Ujala-16, TD-1, and Johar-16 were vulnerable wheat genotypes. The minimum air temperature and relative humidity levels indicated a significant link with the onset of disease. While wind speed and solar radiation revealed no significant link with the development of disease, the maximum air temperature had a negative correlation. The current study's findings highlight the urgent need to incorporate the trifecta of chitosan, salicylic acid, and Bacillus subtilis into the management strategy for SR disease, as well as to develop a disease predicting model based on the current data. Additionally, this research gives up new possibilities for better managing the wheat stripe rust disease.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project No. (IFKSURG-2-470)

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Impact of stripe rust on kernel weight of wheat varieties sown in rainfed areas of Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot.. 2008;40(2):923-929.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stripe Rust Disease Management of Winter Wheat through Host Resistance and Fungicides under Rainfed Conditions in Jammu. India. J. Agric. Sci. Technol.. 2021;23(1):201-207.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of environmental conditions conducive for leaf rust and genetic diversity on wheat crosses based upon physiomorphic traits. Pakistan J. Phytopathol.. 2021;33(1):125-136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yellow rust epidemics worldwide were caused by pathogen races from divergent genetic lineages. Front. Plant Sci.. 2017;8:1057.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of detached leaf assay for assessing leaf rust (Puccinia triticina Eriks.) resistance in wheat. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol.. 2013;4(5)

- [Google Scholar]

- Allelic variation at loci controlling stripe rust resistance in spring wheat. J. Genet.. 2014;93(2)

- [Google Scholar]

- Bonjean, A.P., 2016. The saga of wheat–the successful story of wheat and human interaction. In: Bonjean, A., Angus, W., van Ginkel, M. (Eds.), The World Wheat Book: A History of Wheat Breeding, pp. 1–90.

- Bonjean, A.P., 2016. The saga of wheat the successful story of wheat and human interaction. In: Bonjean, Alain P., Angus, William J., Van Ginkel, Maarten (Eds.), The World Wheat Book: A History of Wheat Breeding, volume 3, Edition Lavoisier Tec&Doc, ISBN 978-2-7430-2091-0, pp. 1672, Chapter 1:1–90.

- Resistance evaluation of differentials and commercial wheat cultivars to stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis) infection in hot spot regions of Canada. European J. Plant Pathol.. 2018;152(2):493-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathogens which threaten food security: Puccinia striiformis, the wheat stripe rust pathogen. Food Secur.. 2020;12(2):239-251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromosomal location of genes for stripe rust resistance in spring wheat cultivars Compair, Fielder, Lee, and Lemhi and interactions of aneuploid wheats with races of Puccinia striiformis. Phytopathol.. 1995;85(3):375-381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wheat stripe (yellow) rust caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Mol. Plant Pathol.. 2014;15(5):433-446.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and control of stripe rust [Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici] on wheat. Canadian J. Plant Pathol.. 2005;27(3):314-337.

- [Google Scholar]

- The branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase TaBCAT1 modulates amino acid metabolism and positively regulates wheat rust susceptibility. Plant Cell Rep.. 2021;33(5):1728-1747.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol.. 2012;13(4):414-430.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of wheat genotypes for leaf rust resistance along with grain yield. Ann. Agric. Sci.. 2015;60(1):29-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- El-Daoudi, Y.H., Shenoda Ikhals, S., Bassiouni, A.A., Sherif, S.E., Khalifa, M.M., 1987. Genes conditioning resistance to wheat leaf and stem rust in Egypt. Proceedings 5th The Egypt Phytopathol. Soci. Giza., 387–404.

- Slow rusting resistance of stem rust in some Egyptian wheat cultivars [Egypt] Minufiya J. Agric. Res. (Egypt) 1985

- [Google Scholar]

- Suppression of wheat stripe rust disease caused by Puccinia Striiformis f.sp. tritici by eco-frienldy bio-control agents correlated with yield improvement. Fresenius Environ. Bull.. 2020;29(9):8385-8393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Feodorova-Fedotova, L., Bankina, B., Strazdina, V., 2019. Possibilities for the biological control of yellow rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in winter wheat in Latvia in 2017–2018.

- Organization of genes controlling disease resistance in the potato genome. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol.. 2001;39(1):79-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chitosan for eco-friendly control of plant disease. Asian J. Plant Pathol.. 2017;11(2):53-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of leaf rust on grain yield and yield traits of durum wheats with race-specific and slow-rusting resistance to leaf rust. Plant Dis.. 2006;90(8):1065-1072.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predicting overwintering of wheat stripe rust in central and northwestern China. Plant Dis.. 2020;104(1):44-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Variation in stripe rust resistance and morphological traits in wild emmer wheat populations. Agron.. 2019;9(2):44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global status of wheat leaf rust caused by Puccinia triticina. Euphytica. 2011;179(1):143-160.

- [Google Scholar]

- The concentration, source and potential human health risk of heavy metals in the commonly consumed foods in Bangladesh. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2015;122:462-469.

- [Google Scholar]

- IPM strategies and their dilemmas including an introduction to www. eurowheat. org. J. Integr. Agric.. 2014;13(2):265-281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of prevalent races of Puccinia triticina Eriks. in Syria and Lebanon. Arab J. Plant Prot. Res.. 2011;29(1):7-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unraveling the efficient applications of secondary metabolites of various Trichoderma spp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2014;98(2):533-544.

- [Google Scholar]

- Control of stripe rust of wheat using indigenous endophytic bacteria at seedling and adult plant stage. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11(1):1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of fungicides and bio-control agents against stripe disease of barley caused by Drechslera graminea. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem.. 2019;8(5):1684-1687.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation of Antimicrobial genes from Oryza rufipogon griff by using a Bacillus subtilis expression system with potential antimicrobial activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2020;21(22):8722.

- [Google Scholar]

- Line, R.F., Qayoum, A., 1992. Virulence, aggressiveness, evolution, and distribution of races of Puccinia striiformis (the cause of stripe rust of wheat) in North America, 1968-87. Technical bulletin-United States Department of Agriculture, (1788).

- Inheritance of leaf rust resistance in wheat cultivars Grandin and CDC Teal. Plant Dis.. 1997;81(5):505-508.

- [Google Scholar]

- Suppression of cadmium concentration in wheat grains by silicon is related to its application rate and cadmium accumulating abilities of cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2015;95(12):2467-2472.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural characterization of stripe rust progress in wheat crops sown at different planting dates. Heliyon. 2020;6(11):05328.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wheat stripe rust epidemics in interaction with climate, genotype and planting date. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.. 2019;154(4):1077-1089.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of certain bioagents on patho-physiological characters of wheat plants under wheat leaf rust stress. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol.. 2019;106(102-108)

- [Google Scholar]

- Chitosan in agricultural context-A review. Bull. Environ. Pharmacol. Life Sci.. 2018;7:87-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.F., Fetch, T., Jin, Y., Prashar, M., Pretorius, Z., 2009. Using race survey outputs to protect wheat from rust. In Proceedings of Oral Papers and Posters, 2009 Technical Workshop, BGRI, Cd. Obregón, Sonora, Mexico. 25–32.

- Molecular basis of Pto-mediated resistance to bacterial speck disease in tomato. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol.. 2003;41(1):215-243.

- [Google Scholar]

- Targeting plant hormones to develop abiotic stress resistance in wheat. In: Wheat production in changing environments. Singapore: Springer; 2019. p. :557-577.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of epidemiological factors on development of Puccinia triticina sp. Tritici on wheat in Pakistan. J. Biol. Agri. Health. 2013;3(19):50-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Weather-data-based model: an approach for forecasting leaf and stripe rust on winter wheat. Meteorol. Appl.. 2020;27(2):1896.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of stripe rust of barley using fungicides. Indian Phytopathol.. 2014;67(2):138-142.

- [Google Scholar]

- The contribution of wheat to human diet and health. Food Energy Secur.. 2015;4(3):178-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rhizosphere competent microbial consortium mediates rapid changes in phenolic profiles in chickpea during Sclerotium rolfsii infection. Microbiol. Res.. 2014;169(5–6):353-360.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mapping Yr28 and other genes for resistance to stripe rust in wheat. Crop Sci.. 2000;40(4):1148-1155.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the effect of leaf rust on the grain yield of resistant, partially resistant, and susceptible spring wheat cultivars. Am. J. Anat. Agric.. 1991;6(3):115-121.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disease impact on wheat yield potential and prospects of genetic control. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol.. 2016;54:303-322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of different fungicides and bioagents, and fungicidal spray timing on wheat stripe rust development and grain yield. Indian Phytopathol.. 2016;69(4):357-362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glyphosate induces human breast cancer cells growth via estrogen receptors. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2013;59:129-136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cereal complex carbohydrates and their contribution to human health. J. Cereal Sci.. 2007;46(3):220-229.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wheat stripe rust control using fungicides in New Zealand. New Zealand Plant Prot.. 2006;59:155-159.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Neolithic Southwest Asian founder crops: their biology and archaeobotany. Curr. Anthropol.. 2011;52(4):237-254.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overwintering of wheat stripe rust under field conditions in the northwestern regions of China. Plant Dis.. 2019;103(4):638-644.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of leaf rust disease on photosynthetic rate, chlorophyll contents and grain yield of wheat. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot.. 2020;53(9–10):425-439.

- [Google Scholar]