Translate this page into:

Determination of the health-protective effect of different Sempervivum and Jovibarba species

⁎Corresponding author. szekelyhidi.rita@sze.hu (Rita Székelyhidi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

This study aimed to examine the micro- and macroelements, as well as the total antioxidant, and polyphenol content of 22 different types of dried houseleek, and fresh plant decoctions. The measurement of antioxidant and polyphenol content was carried out with two drying methods- a drying cabinet and lyophilization. The plants, without exception, were provided by Berger Trio Kft. from Jánossomorja (Hungary), thus, the influencing effect of the environment is negligible in the case of the tested species. Based on the results, the type of houseleek has a clear influencing effect on the amount of the tested constituents. The investigated microelements were B, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn, while Ca, K, Mg, Na, P, and S were examined among the macroelements. In terms of microelement content, Mn was present in outstanding amounts (20.67–148.00 mg/kg DW), while among macroelements Ca (44.43–95.27 g/kg DW) and Na (24.07–128.50 g/kg DW) was present in larger quantities in the samples. It can be said that in the case of samples with a high amount of antioxidants and polyphenols, the element content is low and the reverse is also true. During the examination of the dried houseleeks, outstanding values were obtained for the tested compounds. The antioxidant values of the dried leaves were between 2.22 and 317.74 mg AAE/g DW, while their polyphenol contents ranged from 5.52 to 144.16 mg GAE/g DW, however, the drying methods had some influencing effect. Regarding fresh plant decoctions, the polyphenol contents (0,02–1,11 mg GAE/g FW) were negligible, while the amount of antioxidants (2,38–4,61 mg AAe/g FW) were low. With other solvents (e.g. alcoholic extraction - tinctures), better results are likely to be achieved. Houseleek species (especially in dried form) are an excellent source of trace elements, antioxidants, and phenolic components so they can even be used as additives to functional foods or consumed on their own in the form of encapsulated dietary supplements.

Keywords

Antioxidants

Elements

Houseleek

Polyphenols

Spectrophotometry

1 Introduction

The houseleek comes in a wide variety of shapes, colors, and textures can be found in horticulture, and as a result, there are more than 4,000 varieties (Dégi et al., 2023) Very diverse plant, especially the rosette's diameter, width, and color. It can grow up to 15 cm high and 50 cm wide, with stemless 4–10 cm leaves, but when flowering it can be 20–25 cm. Some varieties has a narrower, more open rosette, and smooth or velvety leaves. Some plants are covered with spider web-like fibers or the tips of their leaves are covered with tiny hairs. Their colors are green, gray, and purple, they can vary in shades of yellow and red, and their tone changes according to the season. The houseleek is an evergreen, perennial, succulent plant. The houseleek rosette contracts in cooler weather and opens in hot weather. It can cling to the roofs of houses with its fibrous roots. In a moderate climate, and good soil, does not require additional nutrients (Fabritzek et al. 2018) It grows most actively in April and May. In summer, it develops from the center of the rosette leaves its inflorescence which is located on a long stem. (Brickell et al. 2008, Jankov et al., 2023). Some varieties bloom for much longer (Kelaidis et al. 2008). After flowering, the houseleek which bearing the flower, dies (Bernáth et al. 2013).

Many beneficial effects of houseleek on human health have been investigated in recent years. It is an excellent source of antioxidants (Šentjurc et al., 2003; Knez Marevci et al., 2021), promotes wound healing (Cattaneo et al., 2019), and has an anti-inflammatory effect. It has a pain-relieving and detoxifying effect and helps the liver to regenerate (Blázovics et al., 1993; Szentmihályi et al., 2004; Muselin et al., 2014; Stojković et al., 2015; Hegyi and Blázovics, 2020). Its favorable physiological effects can be traced back to the phenolic compounds that can be extracted from the leaves (Abram et al. 1999; Alberti et al., 2012).

Only one research is currently dealing with the elemental composition and effects of houseleek on health (Gentscheva et al., 2021a). However, no one has described the relationship between trace elements and antioxidant compounds, especially in the case of the large number (22) species of houseleek described below. In order to reduce the influencing effects of the environment as much as possible, the plants included in the research, without exception, came from the same North-Western Hungarian horticulture (Jánossomorja, Hungary), where the same plant cultivation operations were carried out on them and they were grown in the same composition growing medium. Most of the peripheral region of Western Hungary belongs to the moderately warm, wet, mild winter climate zone. Another characteristic is the low-temperature fluctuation, as well as abundant precipitation at the national level. The region has more than 2,000 h of sunshine per year. The average temperature in the region ranges between 9 and 10 °C.

2 Matherials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

For the ICP-OES analysis nitric acid (lach: ner, Bratislava, Slovakia), and hydrogen peroxide (Molar Chemicals, Halásztelek, Hungary) were used for the destruction method. For calibration, mono-element standards for calcium, potassium, magnesium, and phosphorus, and multielement standards for microelements were purchased from CPAchem (Bogomilovo, Bulgaria). The argon gas required for the operation of the ICP-OES device was procured from Messer Hungarogáz Kft (Budapest, Hungary).

Chemicals for the determination of polyphenol, and antioxidant content were 97 % ethanol (Reanal, Budapest, Hungary), anhydrous sodium carbonate (Riedel-de Haen, Seelze, Germany), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (Merck), 2–4-6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) (Sigma-Aldrich, Budapest, Hungary), acetic acid (Reanal, Budapest, Hungary), anhydrous iron chloride (Merck, Budapest, Hungary), ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Budapest, Hungary), and gallic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Budapest, Hungary).

2.2 Houseleek samples

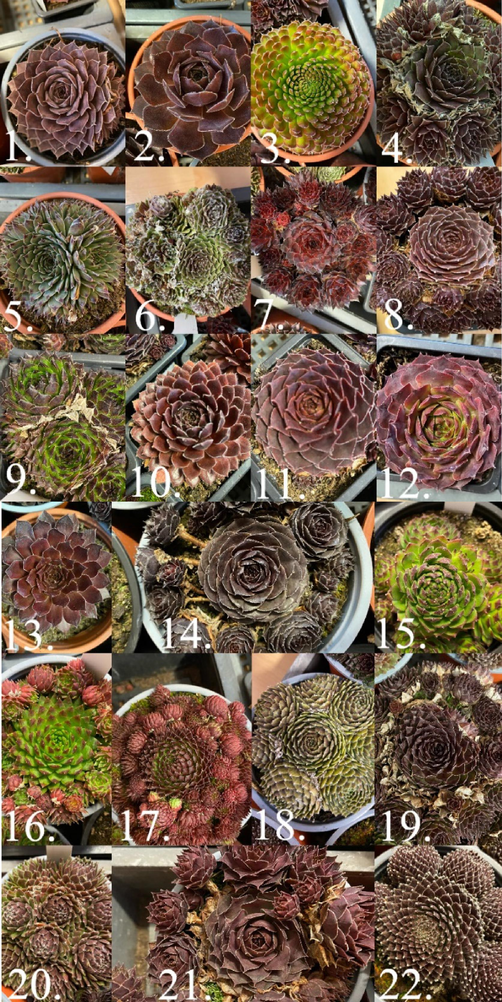

During the experiments, the total antioxidant and polyphenol content of 22 houseleek varieties were examined using spectrophotometric methods, and their elemental composition was also determined using ICP-OES equipment. Each variety of stone rose was in 3 densely overgrown pots with 10.5 cm diameter. The leaves of the same varieties were collected before drying and then divided into 3 equal parts to determine the dry matter content. All samples were subjected to two types of drying - oven drying (Heraeus T6, Germany) at 40 °C, and lyophilization (Flexy-Dry MP, FTS Systems, USA)- until mass was constant. The dry matter content of each sample was determined gravimetrically. The antioxidant and polyphenol contents were examined for both drying methods in order to determine the effect of the drying process and temperature on the compounds. The composition of micro- and macroelements is not affected by the drying method, so they were analyzed only in the case of drying cabinet samples. The dried houseleek samples were chopped with a coffee grinder (Sencor, SCG 2050RD, FAST Hungary Kft., Hungary). The examined houseleek varieties were the following (Fig. 1): ’Sempervivum Tectorum Var. Pyreneum’ ’Sempervivum Pacardian’ ’Sempervivum Orostachys Spinosa’ ’Sempervivum Pilatus’ ’Sempervivum Calcareum’ ’Sempervivum Arachnoideum Webbianum Aureum’ ’Sempervivum Hey-Hey’ ’Sempervivum Granat’ ’Sempervivum Reinhard’ ’Sempervivum For You’ ’Sempervivum Ronsdorfer Hybride’ ’Sempervivum Gamma’

12 ’Sempervivum Celon’

13. ’Sempervivum Mystic’

14. ’Sempervivum Elva’

15. ’Sempervivum Grandiflorum From Nufene Pass’

16. ’Jovibarbara Arenaria’

17. ’Jovibarbara Arenaria Ostirol’

18. ’Sempervivum Koko Flanel’

19. ’Sempervivum Noir’

20. ’Sempervivum Manuel’

21. ’Sempervivum Havendijker Teufel

Houseleek varieties in the experiment.

2.3 Sample destruction

From the dried, and chopped samples, 0.4 g were weighed into a 90 mL tetrafluoromethoxyl (TFM) digestive vessel. To the weighed samples was added 5 mL of 65 % HNO3, and 1 mL of 30 % H2O2. The samples were digested in MARS 6 iWave (CEM Corporation, Matthews, NC, USA) microwave digestion system according to the following program: After a 15-minute heating phase, the destruction was performed at a temperature of 210 °C for 15 min under continuous temperature control. The reaction vessels were cooled, and then the resulting solutions were diluted to a volume of 25 mL with a 0.1 mol/L nitric acid solution. Parallel to the experimental samples, we also prepared blind samples. After digestion, samples were diluted to 25 mL and assayed with ICP-OES.

2.4 ICP-OES analysis

For the determination of the micro-and macroelement composition of the samples an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA) 5110 ICP-OES type equipment was used. We measured the elements shown in Table 2 at the described wavelengths with the settings in Table 1. In the case of the examined macroelements, for the quantitative determination, analytical measuring solutions were prepared in the concentration range of 1–500 mg/L. In the case of microelements, we calibrated in a lower concentration range of 2.5–1000 μg/L.

Parameters

Microelements

Macroelements

Number of elements

5

6

Read time

20

5

RF power (kW)

1.4

Stabilization time (s)

15

Viewing mode

axial

radial

Viewing height (mm)

–

8

Nebulizer flow (L/min)

0.75

Plasma flow (L/min)

12

Aux flow (L/min)

1

Microelements

λ (nm)

Macroelements

λ (nm)

B

249.772

Ca

315.887

Cu

327.395

K

766.497

Fe

238.204

Mg

280.270

Mn

257.61

Na

589.592

Zn

202.548

P

213.618

S

182.562

2.5 Sample preparation for determination of total antioxidant and polyphenol content

To determine the amount of antioxidants and polyphenols in dried houseleek samples, the content of the active ingredient had to be extracted from the matrix by solvent extraction. For extraction, 0.5–0.5 g of samples were weighed into 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks on an analytical balance and 10 mL of an extraction mixture containing ethanol and water (50:50 V/V%) was added. The extraction was performed at room temperature with a laboratory shaker (Elpan 358 S, Poland) for 2 h at 120 rpm. The extracts were centrifugated at room temperature, 2500g, 20 min, and the filtrate was further analysed. We also examined the total polyphenol and, antioxidant content in the watery decoction (tea) of the plants. For this, 5 g of fresh houseleek leaves were scalded with 250 mL of boiling water. After it cooled down, it was filtered and the filtrate was examined.

2.6 FRAP assay

The FRAP assay procedure is based on the method described by Benzie and Strain (1996). 200 µL of extracted sample or tea, 3 mL of FRAP solution, and 100 µL of water were pipetted into a test tube. The finished solutions were placed in a dark place for 5 min and then their absorbance was measured with a Spectroquant Pharo 100 spectrophotometer (Merck, Germany) at a wavelength of 593 nm against the blank. Ascorbic acid (40–500 mg/L) was used as a standard and the results were expressed as ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE)/ g dry matter.

2.7 Folin-Ciocalteu assay

Determination of total polyphenol content based on the Folin-Ciocalteau method described by Singleton et al. (1999) with some modifications (Barba et al., 2013). To 200 µL of houseleek extract or tea, 1.5 mL of high-purity water was pipetted and the reagents were added. First 2.5 mL of 10 % Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, then 2 mL of 7,5 % Na2CO3. The tubes containing the mixture were placed in a dark place for 90 min, and then the absorbance was measured at 725 nm versus the blank. Gallic acid was used as a standard (25–1000 mg/L).

2.8 Data analysis

The total antioxidant, polyphenol, and micro-macroelement contents of houseleek samples and teas were determined in Microsoft Office Excel from the absorbance values measured for the samples using the equation of the second-order least squares analytical curve fitted to the measurement solutions using the nonlinear least-squares method. All the results are expressed as means (n = 3) + / - standard deviation. All measurements were performed in triplicate, and the results are expressed as the mean standard deviation (SD). Analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey post hoc test were used to compare thes ignificant differences in the data. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. The statistical analyses were carried out with Microsoft Excel 2013 software.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Dry matter content of houseleek samples

Table 3 shown the dry matter contents of the houseleek samples after drying to constant mass. In many cases, we detected significant differences in the dry matter content of the examined varieties. The lowest dry matter content had the 'Sempervivum orostachys spinosa' variety with 3.02 m/m% value, in contrast, the 'Sempervivum granat' species had the largest dry matter content (16.79 m/m%). The average moisture content of the plants was 91.21 m/m%. A dry matter content of 10.5 m/m% for Sempervivum tectorum leaves was determined by Mladenović et al. (2021), but in the case of succulent plants, this value also depends on how much moisture they can absorb from the soil and store in their leaves. The examined houseleek varieties were cared for with the same irrigation procedure, so it can be assumed that the differences in the measured dry matter content resulted from morphological differences.

Houseleek species

Dry matter content (g / 100 g FW)

Sempervivum tectorum var. pyreneum

7.25 ± 0.36 g

Sempervivum pacardian

8.47 ± 0.35f

Sempervivum orostachys spinosa

3.02 ± 0.41j

Sempervivum pilatus

11.21 ± 1.11d

Sempervivum calcareum

12.42 ± 0.75c

Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum

11.03 ± 0.03d

Sempervivum hey-hey

14.07 ± 0.79b

Sempervivum granat

16.79 ± 0.08a

Sempervivum reinhard

12.12 ± 0.23c

Sempervivum for you

7.62 ± 0.37 g

Sempervivum ronsdorfer hybride

10.22 ± 0.56d

Sempervivum celon

6.16 ± 0.35 h

Sempervivum mystic

7.10 ± 0.19 g

Sempervivum elva

5.74 ± 0.07 h

Sempervivum grandiflorum from nufene pass

5.37 ± 0.10i

Jovibarba arenaria

6.08 ± 0.26 h

Jovibarba arenaria ostriol

9.72 ± 0.02e

Sempervivum koko flanel

7.84 ± 0.15 g

Sempervivum noir

6.10 ± 0.30 h

Sempervivum manuel

8.92 ± 0.45f

Sempervivum havendijker teufel

7.16 ± 0.15 g

Sempervivum gamma

8.41 ± 0.29f

3.2 Microelement content of houseleek samples

Based on the results presented in Table 4, it can be said that the examined houseleek varieties have a high microelement content, which is influenced by the species. Among the microelements included in the study, the highest value is observed in manganese content. 'Sempervivum pilatus' has the lowest manganese content (20.67 mg/kg), while 'Sempervivum orostachys spinosa' contained the highest amount (140.00 mg/kg). Compared to the received concentrations, the recommended daily intake of manganese for an average, adult human body can be 5 mg (Kiss, 2009). The smallest concentration of boron determined in the variety of 'Sempervivum havendijker teufel' (10.19 mg/kg),while the 'Sempervivum calcareum' species (31.58 mg/kg), contained the largest amount. The least amount of copper measured in the variety 'Sempervivum mystic' (7.43 mg/kg), and the most in the 'Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum' (30.75 mg/kg) species. Regarding zinc, 'Sempervivum mystic' showed the least (16.03 mg/kg), and the variety of 'Sempervivum orostachys spinosa' had the most zinc concentration (85.74 mg/kg). The smallest iron content was obtained in the 'Sempervivum mystic' (13.57 mg/kg) variety, while the highest was in the species of 'Sempervivum havendijker teufel' (67.04 mg/kg). The recommended daily intake is 10–15 mg for iron, 1.1 mg for copper, and 9–10 mg for zinc (Forrai et al. 2020). Compared to the results of the studies presented by Szentmihályi et al. (2004), Turan et al. (2003), and Gentscheva et al., (2021a), we obtained similar results. The elements in the houseleek were better dissolved by the extractant with a higher water content, according to Gentscheva et al., (2021b), so it is assumed that these elements are water-soluble and easily accessed by living organisms.

Houseleek species

B

Cu

Fe

Mn

Zn

Sempervivum tectorum var. pyreneum

24.90 ± 4.78b

12.95 ± 1.87e

24.35 ± 7.91e

54.96 ± 0.10 l

23.31 ± 1.55 g

Sempervivum pacardian

18.63 ± 2.82b,c

7.67 ± 2.88f

17.80 ± 5.78e,f

101.6 ± 1.55c

26.77 ± 2.50 g

Sempervivum orostachys spinosa

31.38 ± 4.13a

10.92 ± 1.21f

52.45 ± 1.38b

148.00 ± 2.39a

85.74 ± 1.35a

Sempervivum pilatus

21.17 ± 5.03b

15.88 ± 1.46d

35.22 ± 2.13c

20.67 ± 12.97o

31.09 ± 10.89b,c,d,e,f,g

Sempervivum calcareum

31.58 ± 3.85a

11.28 ± 5.52d,e,f

36.39 ± 10.63c

84.30 ± 2.81f

42.86 ± 2.58b

Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum

19.71 ± 1.33b

30.75 ± 2.10a

51.44 ± 4.72b

80.63 ± 0.64 g

40.10 ± 0.31b

Sempervivum hey-hey

17.64 ± 0.63c

12.43 ± 5.55d,e,f

25.47 ± 2.30e

59.24 ± 2.32 k

23.19 ± 1.52 g

Sempervivum granat

20.49 ± 1.26b

24.00 ± 0.93b

34.31 ± 0.69c

27.95 ± 0.49o

34.14 ± 4.79e

Sempervivum reinhard

15.75 ± 5.51b,c,d

8.42 ± 6.60d,e,f

21.64 ± 4.99e,f

71.54 ± 0.28h

30.57 ± 2.49e,f

Sempervivum for you

20.16 ± 3.81b

20.12 ± 2.58c

40.05 ± 4.26c,d

58.72 ± 3.31k

32.77 ± 0.97e,f

Sempervivum ronsdorfer hybride

22.56 ± 0.38b

11.99 ± 0.76e,f

24.07 ± 2.02e

55.04 ± 6.27k,l

36.13 ± 2.52d,e

Sempervivum celon

16.06 ± 0.91b,c,d

15.07 ± 1.62d

19.75 ± 3.16f

63.97 ± 2.20j

29.24 ± 1.88e,f

Sempervivum mystic

15.09 ± 0.53d

7.43 ± 1.64f

13.57 ± 6.20f

91.44 ± 2.19e

16.03 ± 0.94h

Sempervivum elva

26.47 ± 2.32b

12.24 ± 2.87e

29.18 ± 0.77e

36.57 ± 1.43m

24.67 ± 2.57g

Sempervivum grandiflorum from nufene pass

14.78 ± 0.90d

17.78 ± 3.56c,d

53.14 ± 3.77b

67.86 ± 0.39i

39.72 ± 0.98c

Jovibarba arenaria

28.11 ± 2.65a,b

14.67 ± 2.99d,e

28.59 ± 1.82e

26.97 ± 2.10o

31.66 ± 2.84e,f

Jovibarba arenaria ostirol

23.29 ± 0.76b

19.77 ± 3.05c,d

41.57 ± 5.51c,d

31.28 ± 1.86n

43.54 ± 1.67b

Sempervivum koko flanel

18.00 ± 0.40c

22.74 ± 3.54b,c

58.82 ± 3.55b

60.68 ± 2.86j,k

33.13 ± 0.56e,f

Sempervivum noir

16.34 ± 1.68c,d

19.89 ± 4.83b,c,d

33.23 ± 0.99c

110.4 ± 0.38b

37.90 ± 0.92c

Sempervivum manuel

23.20 ± 0.71b

8.57 ± 0.10f

28.85 ± 2.67b

81.95 ± 0.90g

29.78 ± 0.31e,f

Sempervivum havendijker teufel

10.19 ± 1.52e

29.13 ± 3.27a

67.04 ± 1.25a

60.93 ± 0.59k

38.71 ± 0.67c

Sempervivum gamma

21.62 ± 1.27b

10.53 ± 0.71f

15.90 ± 3.99f

94.77 ± 0.95d

36.87 ± 0.96d,e

3.3 Macroelement content of houseleek samples

Just like in the case of the microelement contents, the houseleek contains a large amount of macroelements (Table 5). The content of calcium and sodium should be emphasized. The smallest amount of calcium was detected in the case of 'Sempervivum havendijker teufel' (44.43 g/kg), and the lowest sodium concentration was in the 'Sempervivum gamma' (31.63 g/kg) species. The variety of 'Sempervivum orostachys spinosa' has the most calcium, and sodium content, with 95.27 g/kg and 128.5 g/kg values. Regarding potassium the lowest concentration measured in the variety of 'Sempervivum granat' (10.41 g/kg), and the highest in 'Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum' (39.43 g/kg). The least magnesium was detected in the species of 'Jovibarba arenaria' (5.82 g/kg), while the most were contained in the variety of 'Sempervivum orostachys spinosa' (13.51 g/kg). Sulfur and phosphorus, samples showed lower amounts. For sulfur, the 'Sempervivum mystic' (1.83 g/kg) variety contains the least, while 'Jovibarba arenaria ostirol' (9.89 g/kg) variety the most amount. We measured the least concentration in the variety of 'Jovibarba arenaria' (1.88 g/kg), while in the species of 'Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum' (6.05 g/kg) the most phosphorus content. The recommended daily intake is 3.5 g for potassium, 800–1000 mg for calcium, 2 g for sodium, 620 mg for phosphorus, and 300–350 mg for magnesium (Fritz et al. 2019; Forrai et al. 2020). The measured concentrations compared to the result of Szentmihalyi et al. (2004), Turan et al. (2003), Blázovics et al. (2003), and Gentscheva et al., (2021a), get almost similar quantities. The problem with using plants in the food industry is that they can accumulate toxic elements in addition to beneficial elements. Getcheva et al. (2021b) also examined the content of toxic elements in the houseleek extracts using the ICP-MS method, however, the content of titanium, arsenic, cadmium, and mercury was in all cases below the detection limit (0.02 mg/kg) and the highest measured lead concentration was 0.13 mg/kg. Comparing these values with WHO (2007) regulations, according to which the permissible limit value for cadmium in plant samples is 0.3 mg/kg, while for lead is 10 mg/kg, it can be concluded that the stone rose does not accumulate large amounts of toxic elements harmful to health.

Houseleek species

Ca

K

Mg

Na

S

P

Sempervivum tectorum var. pyreneum

71.43 ± 0.32d

11.32 ± 0.32h

8.96 ± 0.74d,e

73.96 ± 1.02e

3.92 ± 1.06d

3.39 ± 0.60b,c,d,e,f

Sempervivum pacardian

71.13 ± 0.23d

11.50 ± 4.06g,h

9.25 ± 0.17d

42.84 ± 5.97i

3.08 ± 1.12d,e

2.18 ± 0.02f,g

Sempervivum orostachys spinosa

95.27 ± 1.84a

21.29 ± 1.11c,d

13.51 ± 2.69a,b,c

128.5 ± 1.40a

8.57 ± 1.37a

5.37 ± 0.39a

Sempervivum pilatus

45.50 ± 13.32f,g,h,i

20.43 ± 2.41c

7.05 ± 2.85e,f

77.81 ± 9.10d,e

2.47 ± 1.68d,e

4.10 ± 0.73b

Sempervivum calcareum

79.70 ± 3.71c

19.36 ± 1.81d

10.97 ± 4.93a,b,c

120.6 ± 5.41b

6.36 ± 1.38a,b,c

3.92 ± 0.66b,c,d,f

Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum

59.07 ± 0.55f

39.43 ± 0.44a

10.70 ± 1.04a,b

93.18 ± 3.91c

5.44 ± 1.46c

6.05 ± 0.63a

Sempervivum hey-hey

63.37 ± 1.37e

16.27 ± 0.18f

9.71 ± 1.48d,e

82.21 ± 4.96d

3.67 ± 1.71d,e

2.52 ± 0.22e,f

Sempervivum granat

49.60 ± 0.60h

10.41 ± 1.27i,j

8.24 ± 0.36e

43.51 ± 0.30i

4.48 ± 1.53c,d

2.24 ± 0.49e,f

Sempervivum reinhard

65.98 ± 6.14e

12.68 ± 6.35e,f,g,h,i

8.12 ± 0.29e

53.10 ± 1.03h

2.29 ± 0.26e

2.88 ± 0.27d,e,f

Sempervivum for you

55.07 ± 0.61g

14.26 ± 3.98f,g

7.53 ± 1.44e,f

71.35 ± 6.72d,e

3.85 ± 1.52d,e

2.40 ± 0.92d,e,f

Sempervivum ronsdorfer hybride

65.55 ± 7.38e

14.41 ± 4.17f,g

8.65 ± 4.39a,b,c,d,e,f

24.07 ± 2.08l

4.40 ± 2.30c,d,e

2.57 ± 0.87d,e,f

Sempervivum celon

75.99 ± 1.43c

12.19 ± 0.64h

9.67 ± 1.49a,b,c,d,e

50.06 ± 5.68g,h,i

3.36 ± 1.37d,e

2.41 ± 0.57d,e,f

Sempervivum mystic

84.88 ± 0.86b

11.50 ± 2.91h

12.47 ± 1.16a,b,c

31.79 ± 3.39k

1.83 ± 0.63e

2.27 ± 0.25e,f

Sempervivum elva

59.57 ± 2.84f

17.47 ± 1.75e,f

8.34 ± 1.68c,d

49.23 ± 3.70h,i

2.96 ± 0.67d,e

2.95 ± 0.02d

Sempervivum grandiflorum from nufene pass

45.94 ± 1.05h

18.57 ± 1.60e

8.12 ± 1.66c,d

58.48 ± 3.96g

4.61 ± 0.86c,d

2.84 ± 0.40d

Jovibarba arenaria

50.55 ± 1.23h

12.83 ± 1.63g,h

5.82 ± 1.31f

45.65 ± 5.45i

8.33 ± 1.18a

1.88 ± 0.86d,e,f

Jovibarba arenaria ostirol

49.01 ± 1.74h

15.65 ± 0.93f

6.25 ± 1.68f

42.28 ± 3.02i

9.89 ± 1.27a

3.12 ± 0.24c

Sempervivum koko flanel

48.62 ± 0.75h

21.79 ± 2.86c

6.99 ± 0.85f

36.59 ± 1.52j,k

5.04 ± 0.94c

3.25 ± 0.25c

Sempervivum noir

80.28 ± 0.26c

14.22 ± 2.98f,g

12.15 ± 0.65b

57.62 ± 4.22g

4.13 ± 1.22d

2.82 ± 0.23c,d,e,f

Sempervivum manuel

63.41 ± 0.06e

13.44 ± 0.53g

8.37 ± 0.11e

38.25 ± 0.63j

6.08 ± 0.08b

3.60 ± 0.59b,c,d,e

Sempervivum havendijker teufel

44.43 ± 1.10i

25.53 ± 0.14b

8.73 ± 0.96d,e

61.59 ± 1.12f

2.94 ± 0.21d,e

3.62 ± 0.56b,c,d,e

Sempervivum gamma

66.52 ± 0.36e

11.39 ± 2.27h

9.39 ± 0.91a,b,c,d,e

31.63 ± 4.77k

4.52 ± 0.98d,e

2.46 ± 0.78c,d,e,f

3.4 Antioxidant content of houseleek samples

Based on the results of Table 6, it can be said that overall better values were obtained using the lyophilization method, but this is not typical for all varieties. The lowest antioxidant content was measured in the species of 'Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum' (2.22 mg AAE/g), this sample was dried in the drying cabinet. The most antioxidants were detected in 'Sempervivum manuel' (305.91 mg AAE/g), in the case of all drying methods. For lyophilized samples, ‘Sempervivum orostachys spinosa’ (41.45 mg AAE/g) contains the lowest concentration of antioxidant compounds, while the most was in 'Sempervivum manuel' (317.74 mg AAE/g). Drawing a parallel between the houseleek varieties and the results, it can be concluded that the antioxidant content is influenced by the variety of plants and the used drying method. To our knowledge, there is no comprehensive publication in the literature that compares the antioxidant content of such a large number of houseleek varieties.

Houseleek species

Total antioxidant content of lyophilized samples

(mg AAE/g DW)Total antioxidant content of oven dried samples

(mg AAE/g DW)

Sempervivum tectorum var. pyreneum

305.87 ± 1.99b

294.55 ± 4.77b

Sempervivum pacardian

122.52 ± 3.16j

252.57 ± 8.10c

Sempervivum orostachys spinosa

41.45 ± 1.53n

7.42 ± 0.11j

Sempervivum pilatus

259.34 ± 5.51e

147.24 ± 7.02g

Sempervivum calcareum

50.51 ± 2.11m

6.30 ± 0.18k

Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum

140.75 ± 15.94i

2.22 ± 0.26l

Sempervivum hey-hey

240.88 ± 9.47f

178.01 ± 7.15f

Sempervivum granat

295.04 ± 8.08c

191.75 ± 9.39f

Sempervivum reinhard

294.63 ± 27.08c

202.15 ± 34.31e,f

Sempervivum for you

279.86 ± 8.19c

220.61 ± 5.64e

Sempervivum ronsdorfer hybride

154.59 ± 1.70i

298.35 ± 9.76b

Sempervivum celon

267.82 ± 2.66d

214.69 ± 38.46e,f

Sempervivum mystic

291.24 ± 20.78c,d

273.70 ± 4.41c

Sempervivum elva

157.07 ± 4.26i

224.95 ± 5.53d,e

Sempervivum grandiflorum from nufene pass

213.19 ± 7.70h

251.79 ± 12.28d,e

Jovibarba arenaria

150.10 ± 9.70i

92.71 ± 1.38h

Jovibarba arenaria ostriol

56.71 ± 1.77l

55.34 ± 3.15i

Sempervivum koko flanel

120.75 ± 3.77k

232.98 ± 30.49e

Sempervivum noir

55.01 ± 6.22l

187.96 ± 9.89f

Sempervivum manuel

317.74 ± 7.88a

305.91 ± 1.62a

Sempervivum havendijker teufel

227.99 ± 5.80g

147.10 ± 4.63g

Sempervivum gamma

316.34 ± 6.84a

283.62 ± 10.80b,c

The used different drying processes resulted in distinct antioxidant values for the same houseleek species. However in terms of the tested compound groups, in most cases, lyophilization eventuated more favorable results, because it is a gentler drying method, thus caused less damaging to the compounds with heat-sensitive antioxidant effects. However, there were samples where on the contrary, oven drying resulted in higher polyphenol and antioxidant content. The reason for these differences could be that the different drying processes caused different plant cell walls' permeability, thus influencing the extraction efficiency, but the applied drying temperatures could also lead to the formation or decomposition of other compounds. Jankov et al. (2023) investigated the free radical scavenging capacity of the Sempervivum tectorum leaf extract and determined that the most typical phenolic compounds with significant antioxidant effects in the houseleek leaves are kaempferol, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, quercetin 3-O-glucoside, caffeic acid, and gallic acid.

3.5 Polyphenol content of houseleek samples

The results of the total polyphenol content of the dried samples are shown in Table 7. Just as in the case of antioxidant contents, clearly illustrates that the amount of polyphenolic compounds is influenced by the type of plant, as well as in most cases these values are more favorable for samples dried with a lyophilizer. Mihai et al. (2019) investigated the phytochemical composition of ‘Sempervivum ruthenicum’ and determined that the most typical polyphenolic acids in the plant are gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, cinnamic acid, p-coumaric acid, and ellagic acid. The sample with the least polyphenol content was 'Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum' (5.63 mg GAE/g), which was dried with a drying cabinet. For this drying method, the highest concentration of polyphenols contained 'Sempervivum tectorum var. pyreneum' (144.16 mg GAE/g). In the case of lyophilized samples 'Sempervivum orostachys spinosa' (19.75 mg GAE/g) contained the least amount of polyphenolic compounds, on the other hand, 'Sempervivum ronsdorfer hybride' contained in highest amount (126.45 mg GAE/g). Comparing the examined results with the article of Knez Marevci et al. (2021), similar polyphenol concentrations are seen.

Houseleek species

Total polyphenol content of lyophilized samples

(mg GAE/g DW)Total polyphenol content of oven dried samples

(mg GAE/g DW)

Sempervivum tectorum var. pyreneum

111.75 ± 3.87b

144.16 ± 7.53a

Sempervivum pacardian

112.27 ± 0.93b

119.20 ± 3.86b

Sempervivum orostachys spinosa

19.75 ± 1.80l

6.07 ± 0.69n

Sempervivum pilatus

81.66 ± 1.33f

52.97 ± 1.70i

Sempervivum calcareum

21.43 ± 0.59l

5.52 ± 0.41o

Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum

58.24 ± 1.51h

5.63 ± 0.45o

Sempervivum hey-hey

80.01 ± 4.48f

66.16 ± 1.95h

Sempervivum granat

90.07 ± 3.29d,e

72.65 ± 8.37g,h

Sempervivum reinhard

87.55 ± 1.58e

81.55 ± 1.91f,g

Sempervivum for you

89.95 ± 2.07d,e

76.01 ± 3.48g

Sempervivum ronsdorfer hybride

126.45 ± 3.66a

97.78 ± 3.97d

Sempervivum celon

78.36 ± 2.41f

80.71 ± 2.45g

Sempervivum mystic

101.17 ± 2.52c

122.71 ± 5.85b

Sempervivum elva

57.00 ± 1.64h

83.66 ± 0.29f

Sempervivum grandiflorum from nufene pass

71.63 ± 0.51g

91.75 ± 1.82e

Jovibarba arenaria

52.65 ± 4.90i

36.30 ± 0.99k

Jovibarba arenaria ostriol

24.07 ± 1.25k

17.90 ± 0.90m

Sempervivum koko flanel

46.68 ± 2.71j

46.13 ± 0.96j

Sempervivum noir

21.78 ± 0.56l

31.23 ± 2.34l

Sempervivum manuel

103.84 ± 5.36c

107.23 ± 4.98c

Sempervivum havendijker teufel

83.26 ± 4.39f

66.33 ± 3.82h

Sempervivum gamma

96.79 ± 5.00d

112.97 ± 3.74c

3.6 Antioxidant and polyphenol content of houseleek decoctions

Regarding the total antioxidant and polyphenol content of teas made from different houseleek varieties, it can be clearly established that significantly fewer antioxidant and polyphenol compounds contain, like dried houseleek plants (Table 8). Plant decoctions containing antioxidant compounds in larger quantities, these amounts to each species are closely similar. The most antioxidants (4.61 mg GAE/g) were in the tea of 'Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum' variety, and the least (2.38 mg GAE/g) was in the 'Sempervivum noir' decoction. Polyphenolic compounds were only present in trace amounts in the teas, higher amounts were contained in the variety of 'Sempervivum tectorum' var. pyreneum' (1.11 mg GAE/g) and 'Sempervivum hey-hey' (0.9 mg GAE/g). Although houseleek tea contains antioxidants, water is not the best extractant to extract these compounds, with other solvents, for example alcohols we could probably achieve better efficiency (Gentscheva et al., 2021b).

Houseleek species

Total antioxidant content of houseleek decoctions

(mg AAE/mL)Total Polyphenol content of houseleek decoctions

(mg GAE/mL)

Sempervivum tectorum var. pyreneum

2.88 ± 0.02c

1.11 ± 0.08a

Sempervivum pacardian

2.67 ± 0.06f

0.20 ± 0.03d,e

Sempervivum orostachys spinosa

2.64 ± 0.04f

0.16 ± 0.04e

Sempervivum pilatus

3.03 ± 0.06b

0.02 ± 0.01h

Sempervivum calcareum

2.67 ± 0.18e,f

0.26 ± 0.05d

Sempervivum arachnoideum webbianum aureum

4.61 ± 0.56a

0.08 ± 0.02g

Sempervivum hey-hey

3.11 ± 0.03b

0.90 ± 0.05b

Sempervivum granat

2.83 ± 0.01f

0.88 ± 0.05b

Sempervivum reinhard

2.62 ± 0.01g

0.05 ± 0.03g,h

Sempervivum for you

2.73 ± 0.05e

0.11 ± 0.03f,g

Sempervivum ronsdorfer hybride

2.59 ± 0.02h

0.05 ± 0.02h

Sempervivum celon

2.52 ± 0.03i

0.02 ± 0.01h

Sempervivum mystic

2.93 ± 0.04b

0.02 ± 0.01h

Sempervivum elva

2.67 ± 0.03f

0.03 ± 0.01h

Sempervivum grandiflorum from nufene pass

2.81 ± 0.05d

0.02 ± 0.01h

Jovibarba arenaria

2.69 ± 0.11f

0.08 ± 0.01g

Jovibarba arenaria ostriol

2.72 ± 0.01e

0.03 ± 0.01h

Sempervivum koko flanel

3.00 ± 0.22b

0.08 ± 0.02g

Sempervivum noir

2.38 ± 0.03j

0.04 ± 0.01h

Sempervivum manuel

2.96 ± 0.18b

0.13 ± 0.01f

Sempervivum havendijker teufel

3.40 ± 0.52b

0.45 ± 0.05c

Sempervivum gamma

3.03 ± 0.05b

0.85 ± 0.15b

4 Conclusion

As a consequence of the research, it can be said that the dried and grounded houseleek contains a large amount of important trace elements for the human body, and accumulates toxic elements below the health risk limit. With the consumption of ground houseleek, we can cover a significant part of the recommended daily intake of micro- and macroelements. After further processing, they can even be sold in the form of capsules as food supplements. Based on the results obtained, the houseleek (primarily in dried form) has physiologically favorable antioxidant and polyphenol content. The amount of compounds is significantly influenced by the houseleek variety. However, we did not see a clear difference regarding the results of the drying procedures. In terms of polyphenol content, lyophilization was more favorable in most cases, we also experienced this with regard to the antioxidant content. Lyophilization is a gentler drying method, thereby causing less damage to the heat-sensitive antioxidant compounds. However, there were results where, on the contrary, the drying cabinet resulted in more favorable values. These disparities may be due to different drying procedures. Each heat treatment made the plant cell walls permeable to varying degrees, thus also influencing the extraction efficiency, but the used temperatures also affect the formation of other compounds, and may lead to their decay. Furthermore, investigated houseleek varieties are likely to contain different amounts of individual antioxidants and phenolic compounds. Although the houseleek decoctions contain antioxidants, water is not the best solvent for the extraction of these compounds. Probably with other extractants, in the form of tinctures, we could achieve better efficiency. Also may be worthwhile to use dried houseleek additives for the production of functional foods. Overall, because of its high element content and excellent free radical scavenging capacity, houseleek may be appropriate for medicinal use. Due to its characteristic, slightly sour taste, it could be used mostly as a supplement to salads, pottages, and confectionery products with an intense taste.

Data availability statement

Authors can confirm that all relevant data are included in the article and/or its supplementary information files.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Tentative identification of polyphenols in Sempervivum tectorum and assessment of the antimicrobial activity of Sempervivum L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999;47:485-489.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of phenolic compounds and antinociceptive activity of Sempervivum tectorum L. leaf juice. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012;70:143-150.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of the analysis of antioxidant activities of liquidfoods employing spectrophotometric, fluorometric, and chemiluminescent methods. Food Anal Methods. 2013;6:317-327.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996;239(1):70-76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bernáth, J., 2013. Vadon termő és termesztett gyógynövények. Mezőgazda Kiadó, Budapest. 640. ISBN: 9789632866741.

- Liver protecting and lipid lowering effects of Sempervivum tectorum extract in the rat. Phytother. Res.. 1993;7:98-100.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reducing power of the natural polyphenols of Sempervivum tectorum in vitro and in vivo+. Acta Biologica Szegediensis.. 2003;47(1–4):99-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- RHS A-Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley; 2008.

- Wound healing activity and phytochemical screening of purified fractions of Sempervivum tectorum L. leaves on HCT 116. Phytochem. Anal.. 2019;30:524-534.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial Activity of Sempervivum tectorum L. Extract on Pathogenic Bacteria Isolated from Otitis Externa of Dogs. Vet. Sci.. 2023;10(4):265.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identity and relationships of Sempervivum Tectorum (Crassulaceae) in the Rhine Gorge area. Willdenowia.. 2018;48:405-414.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Népegészségtan 1. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó; 2020.

- Determination of the Elements Composition in Sempervivum tectorum L. from Bulgaria. Horticulturae. 2021;7(9):306.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optical Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Water-Ethanolic Extracts from Sempervivum tectorum L. from Bulgaria. Horticulturae.. 2021;7(12):520.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Regulation of herbal medicine in Hungary. Int J Complement Alt Med.. 2020;13(1):48-53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing radical scavenging capacity of Sempervivum tectorum L. leaf extracts: An integrated high-performance thin-layer chromatography/in silico/chemometrics approach. J. Chrom. a.. 2023;1703:464082

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kelaidis, G., 2008. Hardy Succulents. Storey Publishing, MASS MoCA Way, North Adams. 160. ISBN 9781580177009.

- Kiss, E., 2009. Vitamin ABC, Könyvmíves Kiadó Budapest 175. ISBN 978-963-9898-20-2.

- The Influence of Extracts from Common Houseleek (Sempervivum tectorum) on the Metabolic Activity of Human Melanoma Cells WM-266-4. Processes.. 2021;9(9):1549.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical Profile and Total Antioxidant Capacity of Sempervivum ruthenicum Koch Hydroethanolic Extract. Revista De Chimie. 2019;70(1):23-26.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Determination of chemical composition of different security extracts. Čačak.. 2021;26:413-421.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective Effects of Aqueous Extract of Sempervivum tectorum L. (Crassulaceae) on Aluminium-Induced Oxidative Stress in Rat Blood. Trop. J. Pharm. Res.. 2014;13:179-184.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of Sempervivum tectorum and its components. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2003;51:2766-2771.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of total phenols and otheroxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152-178.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ethnopharmacological uses of Sempervivum tectorum L. in southern Serbia: Scientific confirmation for the use against otitis linked bacteria. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2015;176:297-304.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic Alterations of Toxic and Nonessential Elements by the Treatment of Sempervivum tectorum Extract in a Hyperlipidemic Rat Model. Toxicologic Pathology.. 2004;32(1):50-57.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Macro and Micro Mineral Content of Some Wild Edible Leaves Consumed in Eastern Anatolia. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica. Section B - Plant. Soil Science. 2003;53(3):129-137.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Assessing the Quality of Herbal Medicines with Reference to Contaminants and Residue; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. 118. ISBN: 9789241594448.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102998.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: