Translate this page into:

Determination of chiral amphetamine in seized tablets by indirect enantioseparation using GC–MS

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The illegal production of amphetamine and its derivatives has rapidly increased in the last years to provide the increasing demand all over the world. Since amphetamine is chiral, its enantiomers have different pharmacological activities. The present work aims to study the enantiomeric profile of amphetamine in several batches of tablets seized from the illegal market. The R and S antipodes were first converted to diastereomers by reaction with trifluoroacetyl-l-prolyl chloride (L-TPC) as chiral reagent. The obtained diastereomers were then full separated by gas chromatography with a resolution factor RS of 1.69, then characterized by mass spectrometry. Both S and R-amphetamine showed similar contents in all investigated samples, with a slight excess of the more active S eutomer. The calculated enantiomeric excess (ee%) values are all positive in the range 0.60–9.72%. The total concentration of amphetamine was from 36.44 to 96.22 mg/g in all tablets. The seized materials showed also the presence of some other ingredients used as additives in manufacturing the tablets such as caffeine, phenazocine, diphenhydramine, dibutyl phthalate and 9-octadecenamide. These findings confirmed that the synthesis of amphetamine used in these tablets was performed using inexpensive and achiral starting substances.

Keywords

R and S-amphetamine

Chiral separation

Derivatization

GC–MS

Seized tablets

1 Introduction

Amphetamine was first synthesized in 1887 and belongs to the phenethylamine class; it is the precursor of a series of related compounds known as substituted amphetamines. It was extensively used during World War II as stimulant in different armed forces (Rasmussen, 2011). Amphetamine has a chemical structure similar to that of ephedrine which was isolated from some Ephedra species. It is widely used for its strong stimulating effects which include increase of awareness, self-confidence, suppression of fatigue, stronger attentiveness, tendency to excitement and relaxation. The compounds related to amphetamine are considered as stimulant drugs of the central nervous system (CNS). This activity is due to the inhibition of the monoamine oxidase enzyme (MAO) which catalyzes the oxidation of biogenic amines, inducing an increase of several neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine in the brain (Fresqui et al., 2013).

However, the use of high doses of amphetamine or its combination with other drugs can induce several negative side effects such as: trembling, psychosis, insomnia, fever and heart palpitation. Moreover, a long-term use of amphetamine or its derivatives may cause severe damages the consumer's body or even death (Weiß et al., 2017). For non-dependent adults, the lethal dose of amphetamine was estimated to 200 mg (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2011).

In the last decades, a lot of new amphetamine derivatives were synthesized and introduced in the illegal drug market; they are widely used as powerful psychoactive compounds known as “legal highs” or “bath salts” (Kadkhodaei et al., 2018; Taschwer et al., 2014; Weiß et al., 2017) The rapid increase of amphetamines consumption throughout all over the world has become a global concern. In order to avoid regulations, the clandestine drug manufacturers used to produce new psychoactive compounds (Lee et al., 2007). The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reported in the EU drug market report that the number of new psychoactive substances introduced in this market was 41 in 2010, 49 in 2011 and 73 in 2012 (Taschwer et al., 2014). One of the reasons for the rapid development of the black market of these new amphetamine derivatives is that they cannot be considered as illicit drugs until they are officially identified and registered (Burrai et al., 2013). Because of the severe side effects and high addiction potential of amphetamine and its derivatives, a lot of countries have limited or completely banned them from their market (Weiß et al., 2014, 2017).

The chirality plays a fundamental role in living organisms, because all proteins are made of amino-acids which have the S absolute configuration. Thus, there is a difference between the biological activity of the two enantiomers of a chiral drug, since their affinity to a specific receptor is not similar. Although some regulations require the use of enantiomerically pure drugs, many pharmaceuticals are still sold in the market as racemates (Singh Sekhon, 2013). Most illegal drugs and some of their additives are chiral and occur as a mixture of stereomers which have different psychoactive properties. Thus, the enantioseparation and determination of each active isomer is important to elucidate the synthetic procedure and the raw materials used for their illegal production (Dieckmann et al., 2008; Weiß et al., 2017).

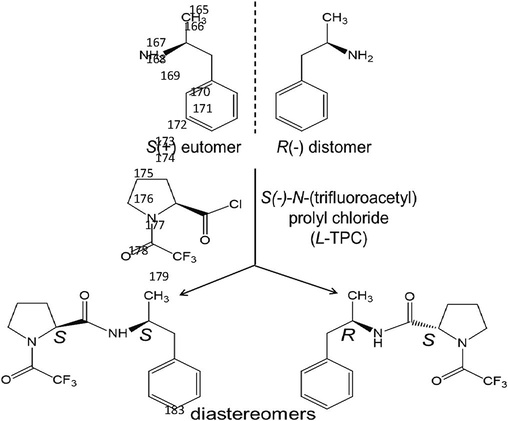

Amphetamine and its derivatives are chiral and have two enantiomers, as shown in Fig. 1. In general, the pharmacological activity of these two antipodes is different: the eutomer exhibits the highest activity while the distomer is less potent. Sometimes this distomer can cause undesirable side effects or even it can be toxic. In the case of amphetamine, the S-enantiomer (eutomer) has stronger effects on the CNS than the R-enantiomer which is the distomer. Many previous reports mentioned that the psychostimulant activity of the S(+) enantiomer of amphetamine (also called dexamphetamine) and related compounds is about five times higher than that of the R(-) enantiomer (or levamphetamine) (Dhabbah, 2019; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2011; Lee et al., 2007; Mohr et al., 2012; Płotka et al., 2011; Weiß et al., 2014) However, it was reported in an article published in 2014 that the R-enantiomer of amphetamine was responsible of its main activity such as stimulation, less appetite and improved performance (Taschwer et al., 2014). Most drugs are present in the market as racemic mixtures, with some other additives (caffeine, lactose, ephedrine, pain killers,…), because consumption of the pure eutomer could be harmful and cause overdose or even death (Nguyen et al., 2006; Weiß et al., 2017).

Amphetamine enantiomers and their diastereomeric derivatives after reaction with L-TPC.

In forensic investigations, the chiral characterization of unknown samples is very useful for identification of the origin of seizures, the precursor materials and the manufacturing process; it can be also used for analysis of biological samples (Mohr et al., 2012; Płotka et al., 2011; Smith, 2009). As an example, since clandestine laboratories use easier and cheaper synthesis procedures which are not enantioselective, most illicit drugs are introduced in the black market as racemic mixtures (Taschwer et al., 2014).

The separation of enantiomers from a racemic mixture is a challenging task in analytical chemistry. It needs the development of an efficient, fast and cheap analytical technique with a high resolution ability for obtention of each pure antipode (Burrai et al., 2013; Dieckmann et al., 2008). There are two paths to separate enantiomers: the direct technique consists on using a column containing a chiral stationary phase. In the indirect procedure, the enantiomers are transformed into diastereomers using a chiral derivatization reagent, then resolved on a standard non-chiral stationary phase (Weiß et al., 2017). In addition, the derivatization process contributes to reduce the polarity of the solutes of interest and increase their volatility and thermal stability; thus, it allows a faster and more efficient enantioseparation (Płotka et al., 2011). For the derivatization of amphetamine and similar drugs, numerous reagents were used such as menthylchloroformate (MCF), 2-methoxy-2-phenylacetic acid (MPA), 2-methoxy-2-trifluoromethyl-2-phenylacetic acid (MTPA), 2-methoxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenylacetyl chloride (MTPACl), trifluoroacethyl-l-prolyl chloride (L-TPC) and heptafluorobutylprolyl chloride (HFBPCl) (Lee et al., 2007; Płotka et al., 2011; Weiß et al., 2017).

Among these derivatization reagents, L-TPC proved to have many advantages since its use is easier and it produces highly resolved diastereomers for testing the enantiomeric purity of various drugs (Płotka et al., 2011; Weiß et al., 2014). Also, the use of L-TPC with new generation of chiral drugs of abuse, such as cathinone, amphetamine and substituted benzo furan derivatives gave satisfactory results (Weiß et al., 2014). Moreover, when compared to other derivatization compounds, L-TPC is most often used because it has several advantages such as commercial availability, ease of use and it provides good resolution (Płotka et al., 2011). On the other hand, many studies showed that the use of L-TPC with almost all amphetamine-type stimulants including ephedrines produces stable derivatives which are conveniently resolved by GC (Hsu et al., 2009; United Nation, 2006).

Several analytical methods were used for enantioseparation and determination of chiral drugs in various samples: high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS), capillary electrophoresis (CE) and supercritical fluid chromatography-mass spectrometry (SFC-MS/MS) (Bagnall et al., 2012; Dieckmann et al., 2008; Holness et al., 2012; Iwata et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2007; Newmeyer et al., 2014; Płotka et al., 2011; Segawa et al., 2019; Weiß et al., 2014). A paper published in 2016 described a multiresidue enantioselective separation of 56 drug biomarkers including amphetamines and other drugs using a chiral CBH (cellobiohydrolase) column by liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (Castrignanò et al., 2016). An enantiomeric profiling of chiral illicit drugs was carried out in European countries; it showed spatial variations in amphetamine contents indicating its higher use in some Northern European regions. Also, the enantioselective analysis displayed enrichment of amphetamine with its R-(−)-enantiomer in wastewater indicating its abuse (Castrignanò et al., 2018).

The present study aims to investigate the distribution of amphetamine enantiomers in different tablets seized in Saudi Arabia. After determination of both S and R-amphetamine present in each sample, the enantiomeric profile of all investigated tablets was evaluated. A further goal is to compare our results to those found in other regions of the world. The indirect enantioseparation of S and R amphetamine was carried out first by derivatization using L-TPC as chiral reagent; their diastereomers were then separated by GC–MS on a common achiral column.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and chemicals

The present study was carried out on twelve amphetamine samples seized in different regions of Saudi Arabia in 2019. Six tablets were randomly selected from each seized batch, then finely ground. A 10 mg sample of the powder was dissolved in 10 mL methanol, then sonicated for 5 min. The solution was then filtered using a 0.45 µm filter. A 100 µL aliquot of the filtered solution was submitted to the derivatization with L-TPC. The pure standards S(+)-amphetamine, racemic amphetamine and S(-)-N-(trifluoroacetyl) prolyl chloride (L-TPC) derivatization reagent were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). A series of standard solutions of S(+)-amphetamine, and racemic amphetamine in methanol were prepared with the following concentrations: 1, 5, 10, 25 and 50 µg.mL−1. In order to convert the amphetamine enantiomers into diastereomers by reaction with L-TPC, their derivatization was conducted using the following procedure. A 100 µL aliquot of the extract solution was transferred into a glass vial with 125 µL of a saturated solution of potassium carbonate, 1.5 mL of ethyl acetate and 12.5 µL of L-TPC. After stirring this mixture at room temperature for 10 min., the upper organic layer was separated and dried by addition of anhydrous sodium sulfate. The solvent was then evaporated using nitrogen until dryness, and 200 µL of ethyl acetate was added to dissolve the L-TPC-derivative. This solution was then injected into GC–MS. A preliminary experiment was conducted on a blank sample spiked with amphetamine. After extraction steps the extract was derivatized then injected; the chromatogram did not show any impurity or degradation product. Fig. 1 shows the structure of S and R-amphetamine, as well as L-TPC and the corresponding diastereomeric derivatives.

2.2 Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry conditions

After derivatization of standard samples and extracts, they were analyzed by GC/MS. Then optimization of the experimental parameters was carried out, the selected conditions used in gas chromatography and mass spectrometry are given in detail below in Table 1. All derivatized standard samples and extracts were injected in triplicate using both full scan and selected ion monitoring (SIM) modes.

Gas chromatography

GC Instrument

Agilent 6890 N GC

Autosampler

Agilent 6890 Series Injector,

Capillary column

HP-5 MSI

Column length

30 m

Inner diameter

0.25 mm

Film thickness

0.25 µm

Injector port temperature

250 °C

Injection mode

Splitless

Carrier gas

Helium

Flow-rate

1.0 mL/min

Sample volume

1 µL

Temperature program

70 °C (2 min.), ramp 12°/min., till 250 °C (1 min.)

Mass spectrometry

MS instrument

Agilent MSD 5973 quadrupole

Ion source temperature

250 °C

Ionization energy of

70 eV

Mass range

50 to 550 Da

MS modes

Full scan and selected ion monitoring (SIM)

3 Results and discussion

Several experimental gas chromatographic conditions were tested for separation of the standard mixture including R(-) and S(+)-amphetamine L-TPC derivatives. After using different temperature programs and carrier gas flow-rates, the best separation was obtained using the optimized method indicated in Table 1.

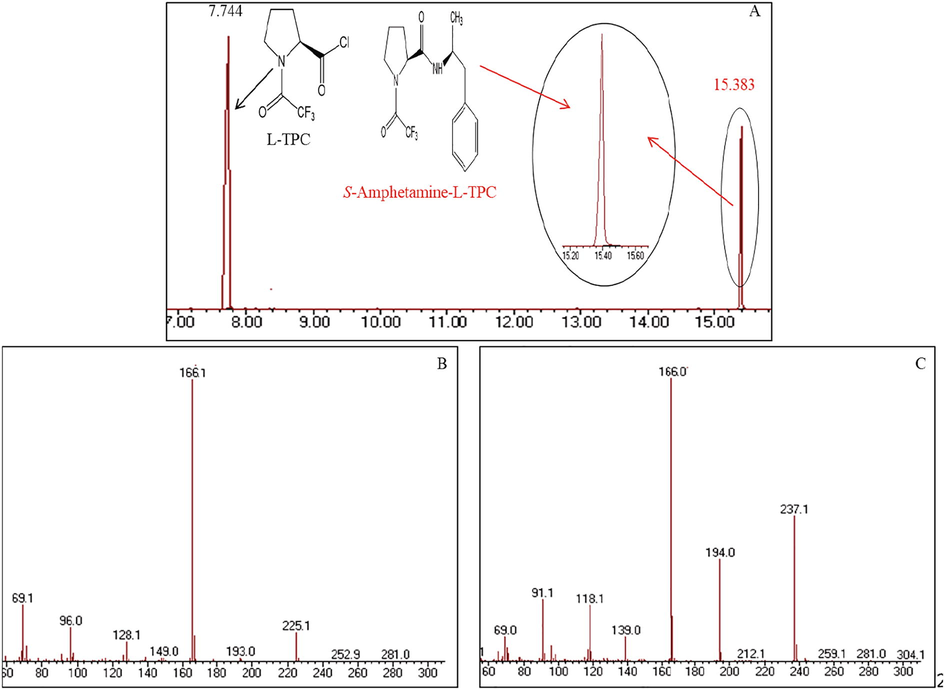

The chromatogram of S-(+)-amphetamine derivatized with L-TPC is shown in Fig. 2A; the two peaks observed at 7.744 and 15.383 min. correspond to L-TPC (excess reagent) and S(+)-amphetamine-L-TPC derivative, respectively. The mass spectra to the two compounds are given in Fig. 2B and 2C. According to this chromatogram the S-(+)amphetamine was totally converted into its corresponding derivative with no presence of any degradation product; this indicates that this amphetamine L-TPC derivative is thermally stable in the used chromatographic conditions. Also, the absence of any other stereomer in the chromatogram means that no chiral inversion occurs during either derivatization or chromatographic steps.

A- Chromatogram of L-TPC excess (7.744 min.) and S-amphetamine derivative (15.383 min.); B and C- Mass spectra of the main components (B: L-TPC, C: S-amphetamine-L-TPC derivative).

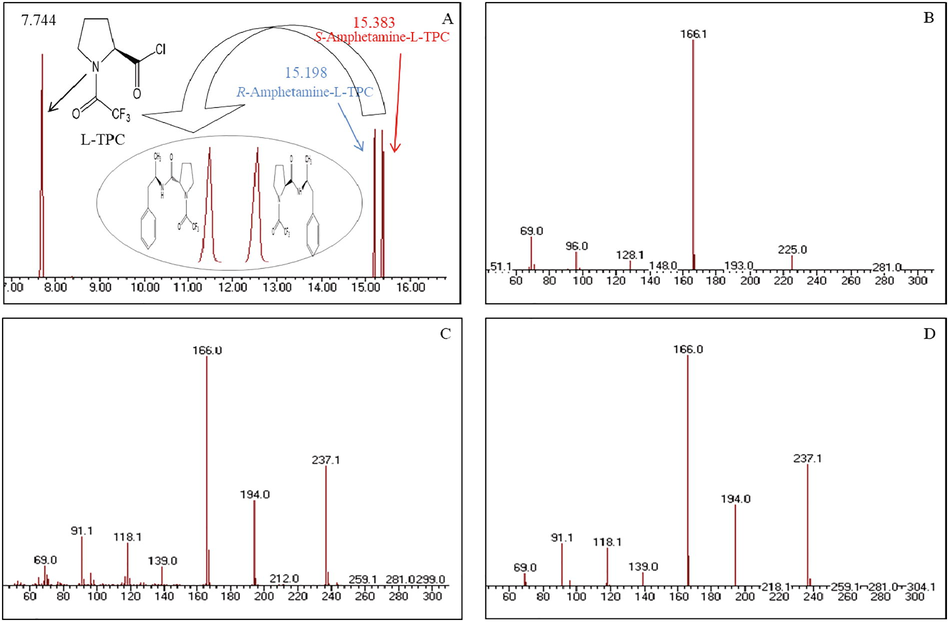

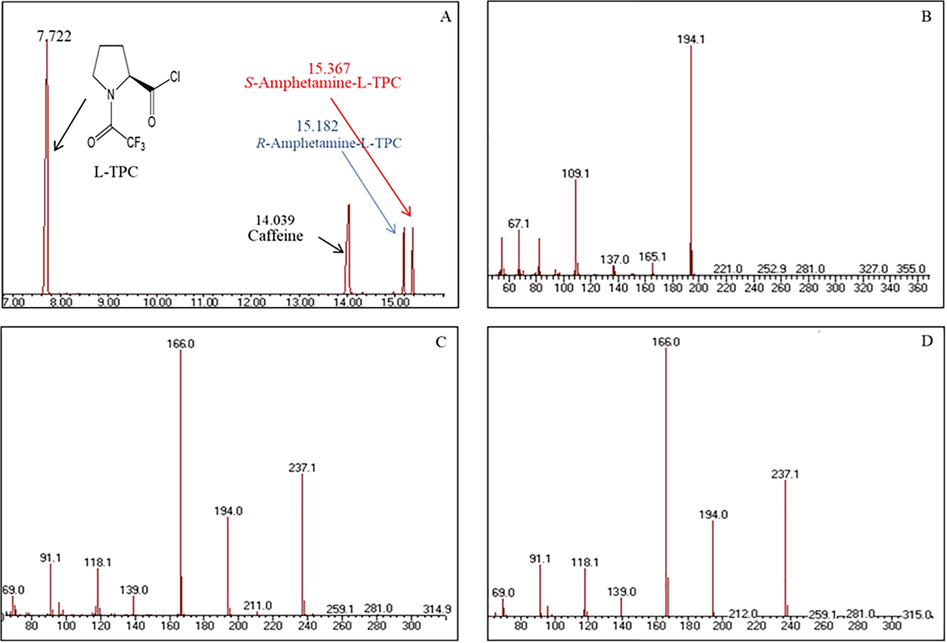

The same derivatization procedure was carried out with the R and S amphetamine racemic mixture which gave the chromatogram showed in Fig. 3A. The peaks eluted at 15.198 and 15.383 min. were assigned to R and S-amphetamine L-TPC derivatives, respectively. The two peaks are fully resolved with a resolution factor RS of 1.69. The mass spectra shown in Fig. 3B, 3C and 3D were assigned to L-TPC in excess, R-amphetamine-L-TPC and S-amphetamine-L-TPC derivatives, respectively.

A- Chromatogram of L-TPC (7.744 min), R + S-amphetamine (15.191 and 15.383 min.) as L-TPC derivatives; B, C and D- mass spectra of the main components (B: L-TPC, C: R-amphetamine-L-TPC derivative, D: S-amphetamine-L-TPC derivative).

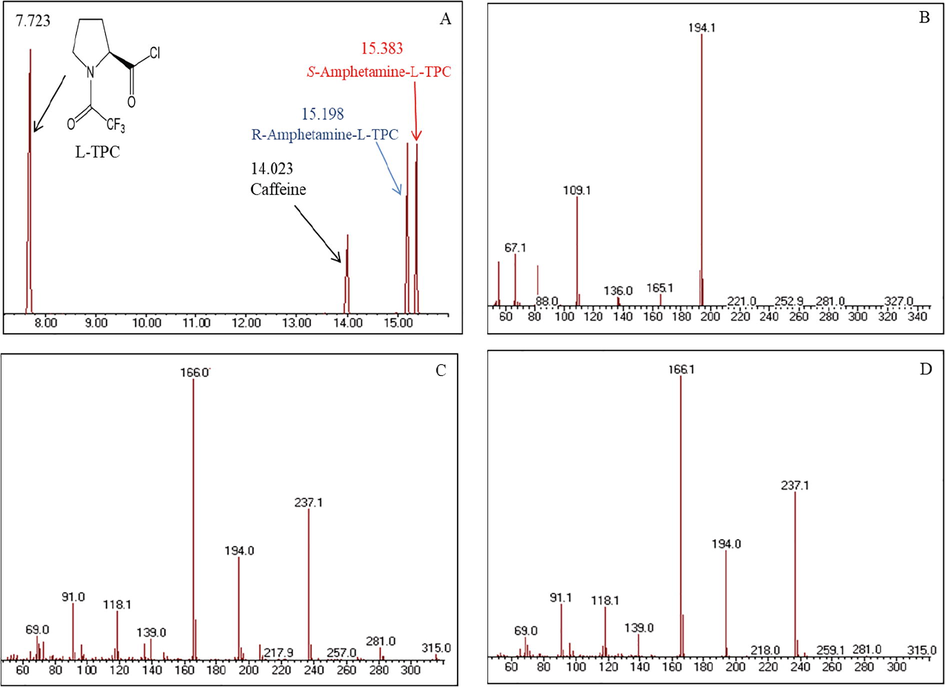

The extracts of the different seized tablets were submitted to the same derivatization procedure with L-TPC, then separated by GC–MS using the same experimental conditions. As example, the chromatograms in Figs. 4 and 5 show the separation of the components extracted from Tablets 1 and 2. Beside the peaks of R and S-amphetamine derivatives, it can be noticed the presence of another peak which corresponds to underivatized caffeine. In fact, all investigated tablets showed the presence of caffeine in various concentrations which were sometimes higher than that of both S and R-amphetamine. Moreover, several other additives were detected in most tablets at lower concentrations, such as: phenazocine, diphenhydramine, dibutyl phthalate and 9-octadecenamide. Among the chemical substances commonly added to illicit drugs, caffeine was often detected as excipient in many seized tablets. Since it is cheap and available, caffeine is frequently used in combination with amphetamine which has similar stimulating effects (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2011; Rasmussen, 2011; Smith, 2009; United Nation, 2006; Weiß et al., 2017). Also, diphenhydramine is associated with many drugs; it was ranked among the most frequently involved substances in drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2017 (Holly Hedegaard et al., 2019). In the fabrication process of clandestine drug, phthalate derivatives such as dibutyl phthalate are often added as lubricant to bind all components in a nice tablet (Devuyst et al., 2007).

A- Chromatogram of extract obtained from Tablet 1 showing the presence of R and S-amphetamine (15.198 and 15.383 min.) after derivatization with L-TPC, which appears at 7.723 min. B, C and D- mass spectra of the main components (B: caffeine, C: R-amphetamine-L-TPC derivative, D: S-amphetamine-L-TPC derivative).

A- Chromatogram Tablet 2 showing peaks of R and S-amphetamine L-TPC derivatives (15.182 and 15.367 min.); B, C and D- mass spectra of the main components (B: caffeine, C: R-amphetamine L-TPC derivative, D: S-amphetamine L-TPC derivative).

Standard solutions of amphetamine with the following concentrations 1, 5, 10, 25 and 50 µg.mL−1 were injected using the same optimized experimental conditions in mass scan and single ion monitoring (SIM) modes. Both calibration curves showed a good correlation with R2 values of 0.9976. The calculated limit of detection of amphetamine was 0.015 µg.mL−1 and the corresponding limit of quantitation was 0.045 µg.mL−1.

Table 2 gives the concentrations of R and S-amphetamine in all investigated samples. The obtained results show that amphetamine is present as racemate in all tablets, since the contents of both R and S enantiomers are approximately the same. This fact confirms the illegal origin of amphetamine which is produced in clandestine laboratories using cheap starting materials.

Tablet weight (mg)

Concentration of R-amphetamine (mg/g)

RSD (%)

Concentration of S-amphetamine (mg/g)

RSD (%)

Total amphetamine (mg/g)

ee%

1

150.77

35.26

3.64

38.36

3.87

73.62

4.21

2

168.67

47.82

3.81

48.40

2.48

96.22

0.60

3

168.82

44.54

2.37

47.78

3.25

92.32

3.51

4

165.55

30.82

3.43

31.62

1.75

62.44

1.28

5

176.65

29.00

2.07

29.78

3.57

58.78

1.33

6

169.18

17.94

3.69

18.5

3.20

36.44

1.54

7

147.95

36.70

3.18

40.44

2.48

77.14

4.85

8

168.70

19.02

2.63

19.86

2.44

38.88

2.16

9

169.03

20.26

3.51

21.10

3.77

41.36

2.03

10

166.75

37.16

2.96

45.16

2.11

82.32

9.72

11

177.45

19.12

2.18

20.26

3.35

39.38

2.89

12

166.06

44.68

1.6

49.66

3.39

94.34

5.28

Among the numerous synthetic routes available for preparation of amphetamine and its related substances, many studies have reported that the Leuckart reaction was the preferred method in clandestine laboratories in many regions around the world (Allen and Cantrell, 1989). Also, the Leuckart reaction allows an easy preparation of a wide range of amphetamines and related compounds using simple and available chemicals, such as phenyl-2-propanone and its analogues (Stojanovska et al., 2013).

On the other hand, the presence of the less active R-enantiomer in the seized tablets available in the illegal market induces lower psychoactive effects and decreases the risk of overdose or even lethal cases (Mohr et al., 2012). The determination of the enantiomeric purity of illicit narcotics is an important aspect to elucidate their source (Stojanovska et al., 2013). The presence of pure R or S amphetamine in the drug indicates the use of a single enantiomer as starting material, such as l-ephedrine or d- pseudoephedrine. However, as it was found in the present study, all of the seized drugs revealed the presence of an approximately equal amount of both enantiomers; this fact suggests that amphetamine, as active substance, was prepared from either achiral or racemic precursors (Allen and Ely, 2009; Stojanovska et al., 2013).

The results reported in Table 2 show that the total concentration of amphetamine in the tablets was in the range from 36.44 to 96.22 mg/g. These values agree with a European report published in 2011 which indicated that the mean purity of amphetamine in seized samples was in the range from 1 to 29% in most countries; while it was observed that its purity was decreasing since 2004 (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2011).

Since amphetamine is a chiral drug, the stimulating activity of each tablet depends not only on the concentration of amphetamine but also on the enantiomeric excess of the S-eutomer (Singh Sekhon, 2013). In order to differentiate the investigated seized tablets, it is important to evaluate the ratio between the two amphetamine enantiomers by calculating the enantiomeric excess ee% using the following formula:where [S] and [R] are the concentrations of amphetamine eutomer S and distomer R, respectively. The values obtained for ee% are reported in Table 2. They show that both amphetamine enantiomers were detected in all investigated tablets. The calculated ee% values are all positive in the range 0.60–9.72%. These results confirm that as shown in the chromatograms, the concentrations of the two amphetamine enantiomers are close together, the S-eutomer being in slight excess in all samples. These findings show that the seized tablets involve racemic amphetamine as psychoactive substance.

4 Conclusion

In the present research, derivatization of racemic amphetamine was carried out by reaction with L-TPC. This reaction yielded two diastereomers corresponding to the S eutomer and R distomer of amphetamine, which were then fully separated by GC–MS and characterized. Twelve batches of seized tablets were investigated using the same analytical procedure. All samples showed the presence of both R and S amphetamine enantiomers in close concentrations. The total content of amphetamine in all seized tablets was between 36.44 and 96.22 mg/g. The enantiomeric excess values were positive and lower than 10% in all samples; this is due to a slight excess of the S-amphetamine eutomer. These results indicate that the probable synthetic route used for preparation of amphetamine was the Leuckart reaction because of its simplicity and it needs use of cheap and achiral starting chemicals. Beside amphetamine enantiomers, some ingredients were also identified in most tablets such as caffeine, diphenhydramine, phenazocine, dibutyl phthalate and 9-octadecenamide.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Synthetic reductions in clandestine amphetamine and methamphetamine laboratories: A review. Forensic Sci. Int.. 1989;42:183-199.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, A., Ely, R., 2009. Review: Synthetic Methods for Amphetamine.

- Using chiral liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry for the analysis of pharmaceuticals and illicit drugs in surface and wastewater at the enantiomeric level. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012;1249:115-129.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enantiomeric Separation of 13 New Amphetamine-Like Designer Drugs by Capillary Electrophoresis. Using Modified-Β-Cyclodextrins. chiraity. 2013;25:617-621.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enantiomeric profiling of chiral drug biomarkers in wastewater with the usage of chiral liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2016

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enantiomeric profiling of chiral illicit drugs in a pan-European study. Water Res.. 2018;130:151-160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Devuyst, E., Lamping, S., Verstraete, A., 2007. Profiling of ecstasy tablets. Gent.

- Dhabbah, A., 2019. Determination of chiral cathinone in fresh samples of Catha edulis. Forensic Sci. Int. 307. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.110105

- Dieckmann, S., Pütz, M., Pyell, U., 2008. Enantiomeric identification of chiral drugs, adulterants and impurities by capillary electrophoresis-ESI-mass spectrometry(CE-ESI-MS), in: Tagungsband Zum XV. GTFCh–Symposium. pp. 509–520.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2011. EMCDDA – Europol joint publications: Amphetamine, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://doi.org/10.2810/49525

- The influence of R and S configurations of a series of amphetamine derivatives on quantitative structure-activity relationship models. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2013;759:43-52.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Holly Hedegaard, M.D., Brigham A. Bastian, B.S., James P. Trinidad, Merianne Rose Spencer, M.W., 2019. National Vital Statistics Reports Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths : United State, 2017. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 68, 1–16.

- Separation mechanism of chiral impurities, ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, found in amphetamine-type substances using achiral modifiers in the gas phase. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.. 2012;404:2407-2416.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Applicability of chemically modified capillaries in chiral capillary electrophoresis for methamphetamine profiling. Forensic Sci. Int.. 2013;226:235-239.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Separation of enantiomers of new psychoactive substances by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Sep. Sci.. 2018;41:1274-1286.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring precursor chemicals of methamphetamine through enantiomer profiling. Forensic Sci. Int.. 2007;173:68-72.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chiral separation of new cathinone- and amphetamine-related designer drugs by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry using trifluoroacetyl-l-prolyl chloride as chiral derivatization reagent. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012;1269:352-359.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid quantitative chiral amphetamines liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: Method in plasma and oral fluid with a cost-effective chiral derivatizing reagent. J. Chromatogr. A. 2014;1358:68-74.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Common methods for the chiral determination of amphetamine and related compounds I. Gas, liquid and thin-layer chromatography. Trends Anal. Chem.. 2011;30:1139-1158.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Medical science and the military: The Allies’ use of amphetamine during World War II. J. Interdiscip. Hist.. 2011;42:205-233.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Simultaneous chiral impurity analysis of methamphetamine and its precursors by supercritical fluid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol.. 2019;37:145-153.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Exploiting the Power of Stereochemistry in Drugs: An Overview of Racemic and Enantiopure Drugs. J. Mod. Med. Chem.. 2013;1:10-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chiral toxicology: It’s the same thing only different. Toxicol. Sci.. 2009;110:4-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review of impurity profiling and synthetic route of manufacture of methylamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethylamphetamine, amphetamine, dimethylamphetamine and p-methoxyamphetamine. Forensic Sci. Int.. 2013;224:8-26.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chiral Separation of Cathinone and Amphetamine Derivatives by HPLC/UV Using Sulfated ß-Cyclodextrin as Chiral Mobile Phase Additive. Chirality. 2014;26:411-418.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recommended methods for the identification and analysis of Amphetamine. Vienna: Methamphetamine and their Ring-Substituted; 2006.

- Indirect Chiral Separation of New Recreational Drugs by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Using Trifluoroacetyl-L-Prolyl Chloride as Chiral Derivatization Reagent. Chirality. 2014;673:663-673.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Indirect chiral separation of 8 novel amphetamine derivatives as potential new psychoactive compounds by GC – MS and HPLC potential new psychoactive compounds by GC – MS and HPLC. Sci. Justice. 2017;57:6-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]