Cytotoxic effects of Annona squamosa leaves against breast cancer cells via apoptotic signaling proteins

⁎Corresponding author. abdelhabib.semlali@greb.ulaval.ca (Abdelhabib Semlali)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Annona squamosa L. is an important medicinal plant used in traditional medicine for the treatment of various diseases. Different parts of A. squamosa L. have various therapeutic effects; however, the anticancer activity of the leaves has not yet been identified. In vitro, MTT, nuclear staining, and LDH assays were used to evaluate cell survival and proliferation in cells exposed to the extracts. The effect of the extracts on cell migration was investigated using a monolayer wound repair assay, and the apoptotic effects were evaluated using flow cytometry. A breast cancer model was used to study the effect of the extract on the tumor size, and the expression of different proliferative and apoptotic markers was evaluated by immunohistochemical analysis. At a concentration of 100 µg/mL, A. squamosa leaf extracts exerted strong antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects against various cell lines. The extracts reduced wound closure and strongly induced apoptosis. In vivo study, rats were sacrificed 24 h after the last injection, and tumor size, as well as the expression of proliferative and apoptotic markers, were observed to be greatly affected by treatment with the extracts. Therefore, A. squamosa leaf extract may be developed as a potential novel drug to treat breast cancer in the future.

Keywords

Annona squamosa

Phytomedicine

Proliferation

Apoptosis

Migration

Estrogen receptor

Tumor size

1 Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer and the most common cause of death in women worldwide (Ferlay et al., 2015). Nevertheless, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy remain the cornerstone of breast cancer treatment (Wang et al., 2014). Chemotherapeutic agents have several disadvantages and significant side effects, such as the inability to differentiate between cancer and normal cells and drug resistance associated with repeated treatment. Hence, there is an urgent need for new drugs. It is necessary to identify natural products that target multiple signaling pathways and cause growth inhibitory effects on cancer cells with fewer harmful effects on healthy cells and the biological environment (Maya et al., 2013). Plant medicines have gained recognition over the last 40 years, and have been widely used as alternative or complementary medicines in many countries and ethnic groups worldwide (Heinrich et al., 2012). Even today, plant-derived compounds play a major role in primary healthcare as natural remedies in most countries, owing to their safety, effectiveness, quality, and availability (Verpoorte, 2009). It is reported that 49% of the 175 small molecules, which were approved for cancer treatment, were natural products or modified natural products. Additionally, it is estimated that almost 80% of people use plant medicines to treat inflammatory diseases (Tundis et al., 2017). Plants with a long history of use in ethnomedicine can be considered a vast resource of bioactive compounds, providing medicinal and health benefits against different diseases (Efferth et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2017). Therefore, in the field of phytoscience, researchers are working to elucidate the side effects, calculate appropriate dosages, and find the best method to extract and identify bioactive components. The bioactive compounds are secondary plant metabolites that elicit pharmacological or toxicological effects in humans and animals; however, one of the most critical challenges that researchers have faced is that a single plant may contain many bioactive compounds (Aḥmad et al., 2006). Currently, there is a global interest in medicinal plants as natural products that may yield the next generation of semi-synthetic derivatives, despite the decrease in the popularity of this approach in the 20th century (Ghazi-Moghadam et al., 2012).

Annona squamosa L. is a small group of an edible plant of the genus Annona and the family Annonaceae, commonly known as a sugar apple or custard apple (Lim, 2012). A. squamosa L. is a small tree that grows to 3–8 m in height and has conical fruits. The leaves are brilliant green on the top and bluish green on the bottom, with petioles of 0.7–1.5 cm long. The shape of leaves is oblong-elliptical; they measure 5 to 17 cm in length and 2 to 7 cm in width, with an obtuse or acuminate apex. The blade has 15 to 17 pairs of veins (Pinto et al., 2005). Different parts of A. squamosa L., such as the bark, root, seed, fruits, flowers, and leaves have been used in traditional medicine to treat various diseases (Kalidindi et al., 2015). Several bioactive compounds have been isolated from A. squamosa L. leaves, including alkaloids, steroids, annonaceous acetogenins, terpenoids, glycosides, saponins, flavonoids, and phenolics (Gowdhami et al., 2014), and these compounds were found to be responsible for various biological activities (Chen et al., 2012a; Wang et al., 2014).

A. squamosa L. plant parts are known to have various biological activities, although there are fewer studies of the leaves. To provide a clear understanding of the mechanism action of A. squamosa L leaf extracts, screening for the anticancer activity should confirm its use as an alternative to chemotherapeutic agents for breast cancer therapy. This study’s objective was to investigate the in vitro and in vivo anti-breast cancer activity of A. squamosa leaf extracts.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material and extraction process

A. squamosa L. leaves were obtained from a local plant nursery in Ta’if City, Saudi Arabia, in December 2016. The identification and authentication were performed by Ibrahim Al-Dakhil, an agronomist, and confirmed by the Department of Botany and Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University (KSU). A voucher specimen (KSU-No. 12068) was deposited at the Herbarium of the College of Science, KSU. The shade-dried leaves were ground into powder using an electric blender. Later, the extract was prepared by maceration of equal amounts of powdered leaves and methanol, acetone, or water (1:10 w/v) for 48 h and then filtered. The filtrate was collected in methanol or acetone and evaporated at 18–21 °C under a fume hood to obtain the crude extracts. For the aqueous filtrate, FreeZone 4.5 Liter Benchtop Freeze Dry System (Labconco, USA) was used for lyophilization. All extracts were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma, USA) for further experiments.

2.2 Cell lines and culture medium

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma) and 2 × 10−3 v/v penicillin–streptomycin (composed of 31 g/L penicillin and 50 g/L streptomycin) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C throughout the assays.

2.3 Cell viability assay

The antiproliferative activity of the extracts was determined by MTT assay following the method of Semlali et al. (2011). The extracts were dissolved in DMSO and then diluted in a culture medium. Briefly, the cells were seeded in 6-well plates (4 × 105 cells/well) and incubated at 37 °C for overnight growth. When cells reached 80% confluence, the culture medium was removed and replaced with 1 mL of fresh culture medium, and the cells were treated with various concentrations of the leaf extract (1 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, and 100 µg/mL) for 24 h. The untreated cells were assayed as a negative control. After that, cells were incubated with 100 µL MTT (5 mg/mL; Sigma) in fresh medium for 3 h. The colored MTT-formazan crystals were dissolved by the addition of 0.04 N HCl in isopropanol (500 µL) to each well. Finally, 100 µL of the reaction mixture was transferred to a 96-well plate, and the maximum absorbance at 550 nm was detected using an ELISA plate reader (X-Mark Microplate Spectrophotometer, Bio-Rad, USA). The experiment was conducted in triplicate.

2.4 Nuclear staining

The morphology of the treated cells was assessed using a Hoechst 33,342 staining assay (H42), as previously described by Semlali et al. (2011). The cells were seeded in 6-well tissue culture plates (3 × 105 cells/well). After overnight incubation, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium. Different concentrations of the extracts were added to the medium, and the cells were incubated for 24 h. The supernatant was then removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed in cold methanol for 15 min. After fixing, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and then stained with 2 µg/mL Hoechst 33,342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, DE) for 15 min. The stained nuclei were washed twice with PBS and observed and photographed using Leica DM2500 & DM2500 LED optical microscopes (LEICA Microsystems, DE).

2.5 Cytotoxicity assay

Breast cancer cell lines were cultured for 24 h in 6-well plates (4 × 105 cells/well). After overnight growth, the culture medium was refreshed, and cells were treated with various concentrations of the leaf extract (1 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, and 100 µg/mL) for 24 h. Cell injury was assessed by the measurement of the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (Smith et al., 2011). 10 µL of the culture supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate, and the enzyme reaction was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (LDH cytotoxicity colorimetric assay kit II, BioVision, USA). Briefly, LDH reaction mixture (100 µL) was added to each well and the plate was incubated for 30 min at 18–21 °C (room temperature) in the dark; thereafter, 10 µL of stop solution was added to terminate the reaction. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an X-Mark microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad). Negative, positive, and background controls for total LDH activity were included in the experiment.

2.6 Monolayer wound repair assay

Breast cancer cell lines were seeded in 6-well plates and grown to confluence. A 10 µL pipette tip was used to made scratch wounds. The detached cells were removed by washing with PBS; thereafter, the cells were treated with 50 µg/mL of the methanolic, acetonic, or aqueous extracts. The migration of cells into the wounded region was observed using a LEICA DFC450 C digital camera (LEICA Microsystems, DE) at 0 and 24 h Semlali et al. (2010). The percentage of wound closure was calculated following the formula:

2.7 Annexin V/PI apoptosis assay

To discriminate the type of cell death induced by A. squamosa leaf extracts, APC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit with PI (BioLegend, USA) was used. This assay is based on the detection of morphological features associated with apoptosis or necrosis. First, the cells were treated with methanolic, acetonic, or aqueous extracts (50 µg/mL) for 24 h; then, adherent cells were collected, rinsed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in 100 µL of annexin-binding buffer. This was followed by the addition of 5 µL APC Annexin V and 10 µL PI solution, and incubation at room temperature for 15 min. Subsequently, 400 µL of annexin-binding buffer was added to the reaction mixture, and the cells were immediately analyzed using BD FACSCaliburTM flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, USA).

2.8 Cell culture conditions for RNA extraction

The breast cancer cell lines were cultured for 24 h in a T25 flask (1 × 106 cells/flask). The culture medium was replaced with medium containing 1% FBS for 24 h, and the cells were then treated with 50 µg/mL of the leaf extracts in 2 mL fresh medium containing 1% FBS, or 0.25% DMSO as the control. The cells were allowed to grow overnight. After washing with PBS, adherent cells were detached by the application of trypsin (Gibco, USA).

2.9 Reverse-Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, DE). The RNA quantity, purity, and quality were determined using a Nanodrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). One microgram of RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the Hyperscript Kit (GeneAll, KR) and random hexamers (GeneAll, KR), as described in the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.10 Quantitative real-times PCR

The mRNA expression of Bcl-2 and Bax was measured using a QuantStudio 7Flex Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The reactions were performed using iTaqTM Universal SYBER Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Primers (Table 1) were added to the reaction mix at a final concentration of 10 pM. Five microliters of each cDNA sample were added to a 20 µL PCR mixture containing 12.5 µL of 2 × iTaqTM Universal SYBER Green Supermix, 0.5 µL of primers for Bcl-2, Bax, GAPDH (Macrogen, KR), and 7 µL RNase/DNase-free water (Qiagen, DE). The thermal cycling conditions for Bcl-2 and Bax were established as 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C, and final 10 s at 95 °C. The specificity of each primer pair was verified by the presence of a single melting temperature peak. The Applied Biosystems software automatically determined the threshold cycle. The expression of GAPDH, a housekeeping gene, was used as an endogenous control for this study.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Product size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCL-2 | Sense | 5′- ACTGAGTACCTGAACCGGCATC-3′ | 108 |

| Antisense | 5′- GGAGAAATCAAACAGAGGTCGC-3′ | ||

| Bax | Sense | 5′- AGTGTCTCAGGCGAATTGGC-3′ | 102 |

| Antisense | 5′- CACGGAAGAAGACCTCTCGG-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | Sense | 5′- GGTATCGTGGAAGGACTCATGAC-3′ | 188 |

| Antisense | 5′-ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAGC-3′ |

2.11 Animal model

To confirm the in vitro results, twelve female Wistar albino rats (Rattus norvegicus), aged 5–8 weeks of age and with a bodyweight of 110 ± 20 g were used. The rats were divided into three groups, with four animals in each group. The rats were obtained from the breeding facility at the College of Pharmacy at King Saud University, Riyadh, and the written informed consent to use the animals in our study was obtained from this facility. The animals were housed in plastic cages at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) with a constant relative humidity (45% ± 5%) under a 12 h light/dark cycle. Mammary tumors were induced in two groups of rats (groups I and II) by a single subcutaneous injection in the pectoral area with the potent carcinogen, dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA), as described previously (Bersch et al., 2009). After tumor palpation (8 weeks post-injection), animals in group I received corn oil as vehicle control, whereas animals in group II were injected with A. squamosa aqueous extract dissolved in corn oil at a dose of 300 mg/kg directly into the tumor. A single dose was injected for 4 weeks every 48 h, following a previously described protocol (Ait M'Barek et al., 2007; Zyad et al., 1995). After treatment, the rats were euthanized by administering a ketamine (125 mg/kg), and xylazine (10 mg/kg) overdose and mammary gland tissues were collected from all sacrificed rats. All animal procedure was reviewed and approved in accordance with ICH GCP guidelines by the Institutional Review Board at King Fahd Medical City, Riyadh, KSA (IRB log number: 18–586, registration number with KACST, KSU: H-01–12-012 and registration number with OHRP/NIH, USA: IRB00010471).

2.12 Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis

Polyclonal antibodies were used to assess the expression of different tumor markers, including the genes involved in the proliferation signaling pathway, such as Ki67 and p53. Briefly, IHC was performed on 3-μm slices of deparaffinized and rehydrated breast tissue by a Ventana Benchmark XT automated staining (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ) for the assessment of Ki67 and p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), as previously described by Semlali et al. (Semlali et al., 2016). The immuno-stained sections were analyzed by an Olympus BX51 light microscope and DP72 Olympus digital camera with powers 400X (Olympus America Inc, Center Valley, PA, USA).

2.13 Statistical analysis

Data are presented as an arithmetical mean ± standard deviation (±SD) using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v.21, Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical differences were evaluated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by student’s t-test. p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant, while value ≤0.005 was taken as statistically highly significant compared to relevant control.

3 Results

3.1 The effect of A. squamosa extract on cell survival

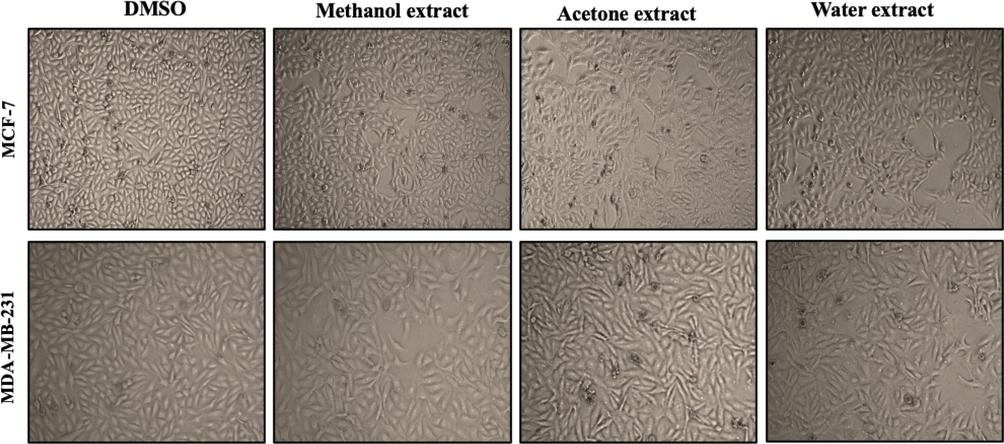

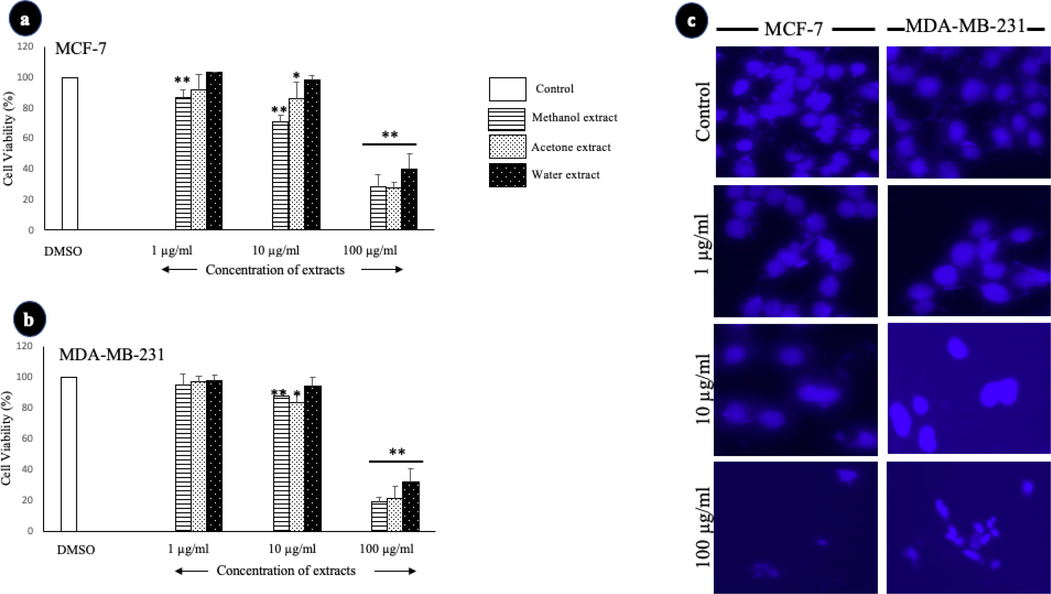

Treatment with A. squamosa leaf extracts did not induce clear changes in the morphology of either breast cancer cell line; however, the treatment affected the number of viable cells (Fig. 1). Therefore, the antiproliferative activity of various concentrations of A. squamosa extracts was determined against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines using MTT assay. The methanolic extract resulted in a highly significant decrease in MCF-7 cell viability at 1 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, and 100 µg/mL (Fig. 2-a). The 10 µg/mL of the methanolic and acetonic extracts resulted in a highly significant decrease in the viability of MDA-MB-321 cells (Fig. 2-b). However, it was found that all three extracts of A. squamosa leaf at 100 µg/mL resulted in a highly significant decrease in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-321 cell viability, with cell proliferation inhibition of approximately 60%. Furthermore, to determine whether the antiproliferative activities of A. squamosa extracts were related to the induction of apoptosis, the morphological changes of cells were investigated using a nuclear staining assay. In both cell lines, the number of cells decreased with an increase in the extract concentration applied. Besides, nuclear damage occurred in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2-c). These results clearly showed the antiproliferative activity of A. squamosa extracts in ER+ breast cancer cells, MCF-7, and ER- cells, MDA-MB-231.

- The effect of A. squamosa extracts on the morphology of breast cancer cell lines. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at 4 × 105 cells/well and treated with 50 µg/mL methanol, acetone, or aqueous extract in DMEM medium with 10% FBS. Photomicrographs were taken at 24 h.

- The effect of A. squamosa extracts on the proliferation of breast cancer cell lines as determined by MTT and nuclear staining assays. The cell viability of MCF-7 cells (a) and MDA-MB-231 cells (b) in the MTT assay (n = 5). (c) Photomicrographs of breast cell lines treated with three different concentrations of methanolic extract of A. squamosa leaves. The control cells were treated with DMSO (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005).

3.2 The cytotoxic effects of A. squamosa extracts

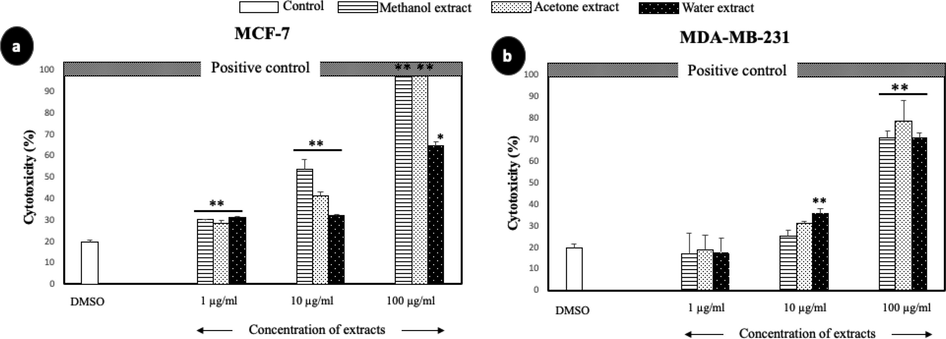

The cytotoxicity of A. squamosa extracts was determined through the measurement of LDH leakage from degraded cells, which resulted from the cytotoxic effects of the extract. As shown in Fig. 3, the extracts exerted cytotoxicity against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 in a dose-dependent manner. Overall, the three different extracts showed highly significant cytotoxic effects in ER+ cells, MCF-7, compared with the ER- cells, MDA-MB-231. At the highest concentration tested (100 µg/mL), the methanolic and acetonic extracts induced 100% cell death in MCF-7 cells, and the aqueous extract induced approximately 60% cell death. A. squamosa extracts resulted in approximately 70%–80% cell death of MDA-MB-231 cell lines at the highest concentration tested (100 µg/mL).

- The cytotoxic effect of A. squamosa extracts against breast cancer cell lines as determined by LDH assay. MCF-7 (a) and MDA-MB-231 (b) breast cancer cell lines. DMSO and Triton X-100 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005).

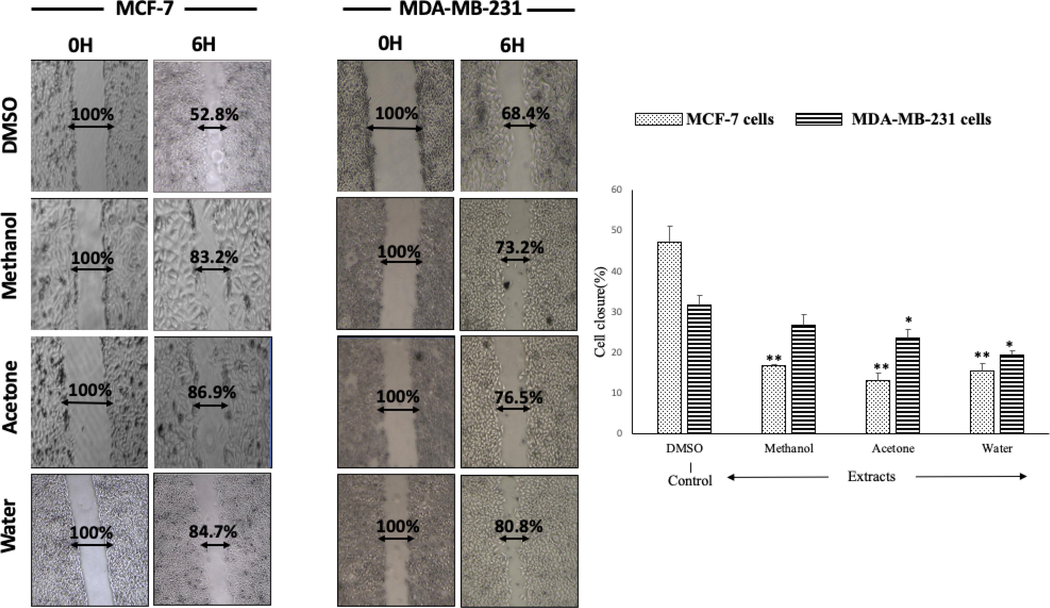

3.3 The effect of A. squamosa extracts on cell migration

To clarify the potential of A. squamosa extracts as anticancer agents, the effect of the extracts on the migration of cancer cells was tested using a monolayer wound healing assay (Fig. 4). After 6 h, the cells treated with extracts had not migrated as far as the untreated cells. Furthermore, MCF-7 cells treated with the three different extracts showed 30%–33% less closure after 6 h than the DMSO-treated control cells (p < 0.005). It appears that the healing of ER- cells occurred much more rapidly than ER + cells; therefore the migration of MDA-MB-231 treated cells was not greatly affected. In other words, the decrease in cell migration resulting from A. squamosa extract treatment was more considerable in ER + cells.

- The migration of breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231) after treatment with different A. squamosa extracts. A scratch was made on each monolayer, the culture medium was refreshed, and 50 µg/mL of extract was added. The cultures were maintained under the appropriate conditions, observed, and photographed at 0 and 24 h (n = 3, *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.005).

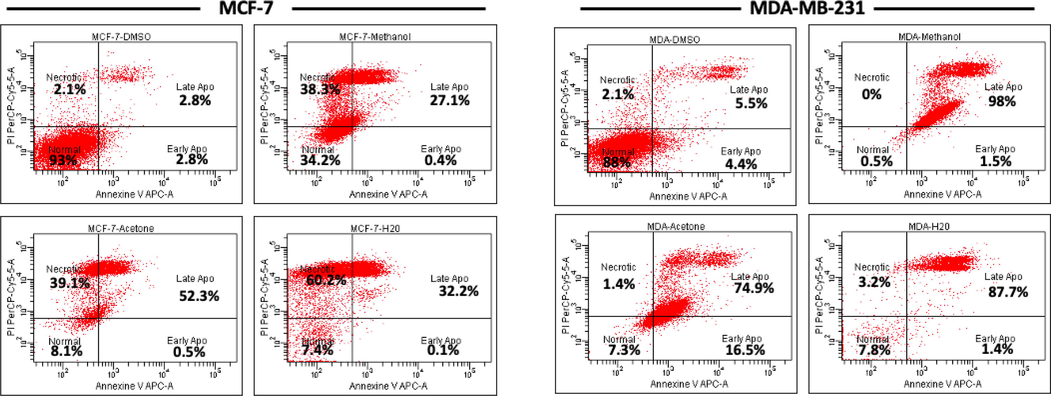

3.4 The apoptotic effect of A. squamosa extracts

The effect methanolic, acetonic, and aqueous extracts of A. squamosa leaves on apoptosis induction in the breast cancer cell lines were measured using Annexin V/PI staining after 24 h of treatment at 50 µg/mL (Fig. 5). For MCF-7 cells, the percentage of normal cells decreased by 65.8%, 92%, and 92.6% after treatment with the methanolic, acetonic, and aqueous extracts. The methanolic extracts induced apoptosis in 27.5% of the cells, and necrosis in 38.3% of the cells. Apoptosis was induced in 52.8% of cells and necrosis was induced in 39.1% of cells treated with the acetonic extract. However, the aqueous extract was found to have the most potent effect on MCF-7, inducing necrosis in 60.2% of cells and apoptosis in 32.3% of cells. In contrast, the methanolic extract induced apoptosis in almost all MDA-MB-231 cells (99.5%), the acetonic extract induced apoptosis in 91.3% of cells, and the aqueous extract induced apoptosis in 89% of cells.

- Survival of breast cancer cells after treatment with A. squamosa extracts for 24 h. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at 4 × 105 cells/well and treated with 50 µg/mL methanol, acetone, or aqueous extract in DMEM medium with 10% FBS for 24 h. The apoptotic effect was measured using Annexin V-PI staining kit and flow cytometry.

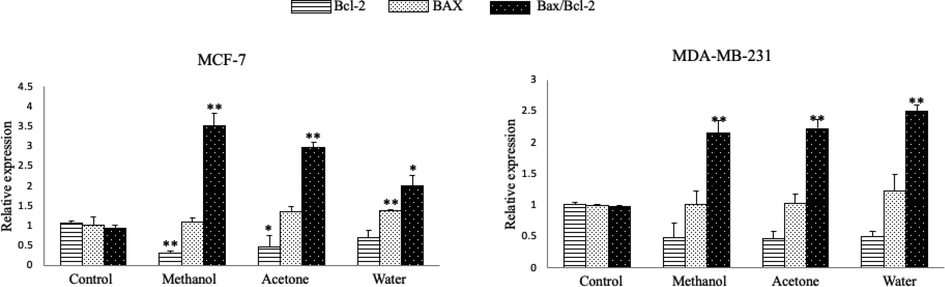

3.5 The effect of A. squamosa extracts on anti-apoptotic/pro-apoptotic gene expression

To detect the apoptotic effects of the methanolic, acetonic, and aqueous extracts, the expression of anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2) and pro-apoptotic (Bax) genes in breast cancer cells were measured using qPCR. The exposure of MCF-7 cells to the extracts caused downregulation of the Bcl-2 mRNA; this change was significant after treatment with the methanolic and acetonic extracts. All three extracts upregulated the expression of Bax; however, the change was only significant after treatment with the aqueous extract (Fig. 6-a). In MDA-MB-231 cells, the expression of Bcl-2 was downregulated, and that of Bax was upregulated (Fig. 6-b). Therefore, these findings showed that A. squamosa extracts induced apoptosis through the suppression of Bcl-2 and the activation of Bax. Consequently, the Bcl-2/Bax ratios showed a highly significant decrease (P < 0.005).

- Relative mRNA expression of Bax and Bcl-2 in breast cancer cells treated and untreated with A. squamosa extracts for 24 h. (a) MCF-7 cell lines. (b) MDA-MB-231 cell lines. The data are expressed relative to the values for untreated control cells and represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3, *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.005).

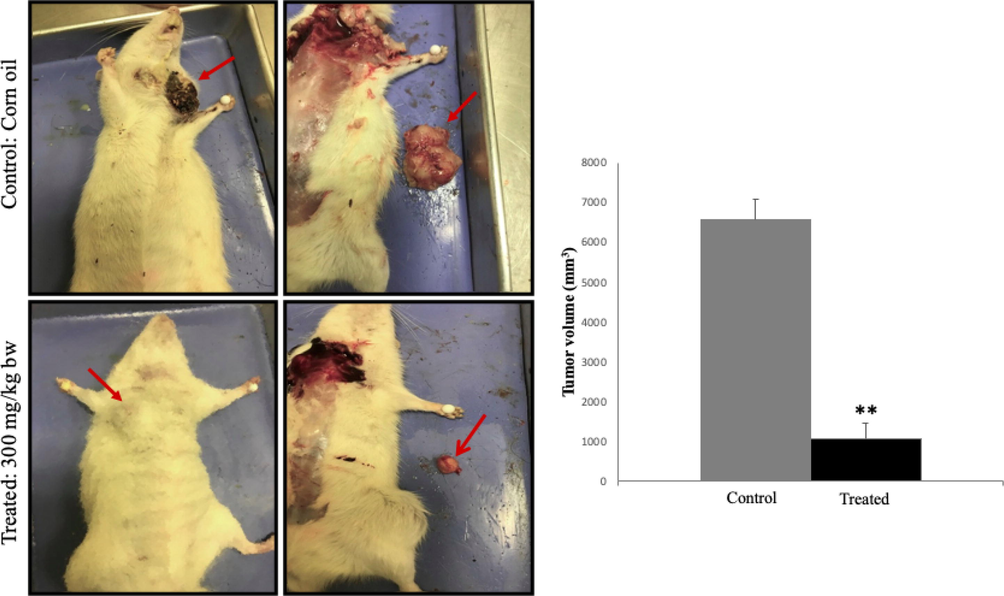

3.6 In vivo effect of A. squamosa extract on tumor growth

The therapeutic effects of A. squamosa extract in a rat model of breast cancer were assessed after treatment, via local injection, with the aqueous extract for one month. Aqueous extract of A. squamosa was used as a starting point, to eliminate any side effects of using the organic solvents in the existing system. As shown in Fig. 7, the tumor size in the treatment group was significantly reduced compared with that of the control (corn oil-treated) group, 1083 mm3, and 6583 mm3, respectively. These data suggested that the local treatment of A. squamosa extract significantly reduced the development and progress of tumor formation.

- Test of A. squamosa extract treatment on size of breast tumor induced by DMBA. (a) Injecting A. squamosa aqueous extract (300 mg/kg body weight) into the breast cancer model inhibited the tumor growth when compared with the control group. (b) Tumor size was measured with a caliper and calculated using the formula: (Length × Width2)/2, (n = 3, *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.005).

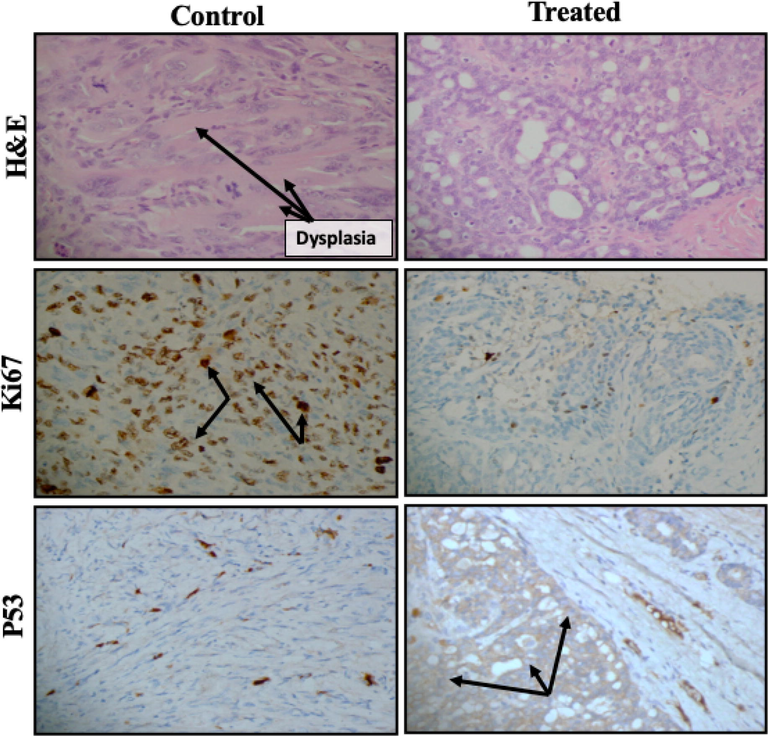

These results were confirmed by histological analysis of the tumor tissues, which revealed a more aggressive metaplastic carcinoma in the untreated rats than the treated rats (Fig. 8). In the immunohistochemical analysis, less intense positive immunostaining of Ki67, a well-established marker for tumor cell proliferation, in treated tissue compared to untreated tumor tissues. Moreover, the expression of p53, a tumor suppressor gene, was more intense in the treated tumor tissues than in the untreated tumor tissues. Overall results were indicating a pronounced decrease in proliferation and increase in apoptosis, in the treated tumor tissues.

- Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of cell proliferation and apoptotic markers following treatment with aqueous extract (300 mg/kg body weight) in the rat model of breast cancer. Representative treated and untreated rats were used for the evaluation. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used for the histopathological examination, whereas antibodies for Ki67 and p53 were used for immunohistochemical staining. Magnification 400×.

4 Discussion

From ancient times, plants have been used for the treatment of diseases by humans. They are used as complementary medicine or to synthesize chemical compounds. According to the World Health Organization, more than 80% of the world’s population depends on nature-derived traditional alternative medicine for their primary healthcare needs (Bailon-Moscoso et al., 2016, Semlali, et al., 2021, Contant, et al., 2021). One of these plants with extensive traditional use is A. squamosa; however, biologically, it is less well characterized. Few studies have illustrated the anticancer activity of A. squamosa leaf extracts. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the anticancer effect of A. squamosa leaf extract on breast cancer cells.

In the current study, the anticancer activity of A. squamosa leaf extracts was investigated in vitro against two breast cancer cell lines; MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231. Our results revealed that the different A. squamosa leaf extracts did not induce any changes in the morphology of the cell lines (Fig. 1). However, different extracts were found to induce cytotoxicity and inhibit the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 2 and 3). In this study, the antiproliferative and cytotoxicity activities of the extracts were confirmed by nuclear staining, which revealed damaged nuclei (Fig. 2-c). These appear to be consistent with the results of a recent study on the isolation of different acetogenin compounds from A. squamosa seeds; the compounds were able to suppress the proliferation of multi-drug resistant MCF-7 cells via cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase (Ma et al., 2017). Indeed, it is well known that the leading cause of death among patients with cancer is the ability of cancer cells to metastasize and invade (Seyfried and Huysentruyt, 2013), and our results present the first demonstration that different A. squamosa leaf extracts partially inhibited breast cancer migration (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the current study showed that different extracts induced late apoptosis and necrosis in both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5). These results were confirmed by the study of the gene expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic markers, and different extracts were found to induce the expression of Bax and suppress the expression of Bcl-2 (Fig. 6). These results agreed with those of Pardhasaradhi et al. (2005), which showed that treatment of MCF-7 with A. squamosa seed extracts resulted in nuclear condensation, DNA fragmentation, ROS generation, and apoptosis induction via downregulation of the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax. The remarkable anticancer activity of the extracts may due to the high level of germacrene-D on the leaves which exerted anticancer activity against different cell lines, or to the presence of other bioactive compounds which have also been known to have an anticancer activity such as humulene, phytol and/or a combination of these bioactive compounds (Essien et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2015; Pejin et al., 2014). Collectively, methanolic extracts have the highest total phenolic content and germacrene-D, while acetonic extract have the highest total flavonoid content, these differences on the ratio of the bioactive compounds explain the potential differences between the three extracts (Alnemari et al., 2020).

An in vivo study can offer conclusive insights about the nature of the biological effect of A. squamosa leaf extracts; therefore, a breast cancer model developed in our laboratory was used. It was interesting to note that aqueous extracts significantly decrease tumor size. To better understand the mode of action of the extracts, immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate the expression of proliferative and tumor suppressor genes, Ki67, and p53. Stronger immunostaining intense for p53 was found in the treated tissue than the control one, and less intense staining Ki67 was observed in the treated tissue. This finding was consistent with those of Chen et al. (2012b), which showed that A. squamosa seeds extracts inhibited the growth of H22 hepatoma cells by 69.55% in mice without any side effects. According to these results, we can infer that p53 directly or indirectly targeted either the apoptotic or non-apoptotic cell death pathway. For example, Caspase-3 activation drives the expression of different microRNA species that are known to target the Bcl-2 or the expression of different genes that are involved in cell cycle arrest (Aubrey et al., 2017).

5 Conclusions

In summary, A. squamosa leaf extracts demonstrated potential anticancer activity against breast cancer in both in vitro and in vivo experiments; therefore, further investigation may contribute to the development of a potential new anticancer therapy for both ER + and ER- breast cancer. Further research is needed to fully understand the mechanism of action of A. squamosa leaf extracts and its role in cell autophagy, in order to identify the pathway targeted by these extracts.

Author contributions

RA, ABB, and AS conceived and supervised the research. RA conducted the experiments, analyzed, and interpreted the data. RA, ABB and MHA drafted the materials and methods section. NA, MA, and HA helped with animal experiments. RA and AS completed the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (IRB log number: 18–586, Registration number with KACST, KSU: H-01–12-012 and Registration number with OHRP/NIH, USA: IRB00010471). The rats were obtained from the breeding facility at the College of Pharmacy at King Saud University, Riyadh and the written informed consent to use the animals in our study was obtained from this facility.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/191), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

References

- Modern phytomedicine : turning medical plants into drugs. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2006.

- Cytotoxic effect of essential oil of thyme (Thymus broussonettii) on the IGR-OV1 tumor cells resistant to chemotherapy. Brazilian J. Med. Biol. Res. = Rev. Bras. Pesqui. medicas e Biol.. 2007;40(11):1537-1544.

- [Google Scholar]

- How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ.. 2017;25(1):104-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of extracts from Annona montana M. fruit. Food Agric. Immunol.. 2016;27(4):559-569.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of nicotine and cigarette smoke on an experimental model of intraepithelial lesions and pancreatic adenocarcinoma induced by 7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene in mice. Pancreas. 2009;38(1):65-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Six cytotoxic annonaceous acetogenins from Annona squamosa seeds. Food Chem.. 2012;135:960-966.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-tumor activity of Annona squamosa seeds extract containing annonaceous acetogenin compounds. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2012;142:462-466.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anethole induces anti-oral cancer activity by triggering apoptosis, autophagy and oxidative stress and by modulation of multiple signaling pathways. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1)

- [Google Scholar]

- From traditional Chinese medicine to rational cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13(8):353-361.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil constituents, anticancer and antimicrobial activity of Ficus mucoso and Casuarina equisetifolia leaves. Am. J. Essent. Oil. Nat. Prod.. 2016;4:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:359-386.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytomedicine in otorhinolaryngology and pulmonology: clinical trials with herbal remedies. Pharm.. 2012;5:853-874.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Screening of Phytochemicals and Antibacterial Activity of Annona Aquamosa Extracts. IJPSI. 2014;3:30-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fundamentals of Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy (2nd ed.). Elsevier; 2012.

- Antifungal and antioxidant activities of organic and aqueous extracts of Annona squamosa Linn. leaves. J. Food Drug Anal.. 2015;23(4):795-802.

- [Google Scholar]

- Activation of Caspase-9/3 and inhibition of epithelial mesenchymal transition are critically involved in antitumor effect of phytol in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Phytother. Res.. 2015;29(7):1026-1031.

- [Google Scholar]

- Annona squamosal. In: Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 1, Fruits. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2012. p. :207-220. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8661-7_30

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on Annona squamosa L.: phytochemicals and biological activities. Am J Chin Med. 2017;45(05):933-964.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytomedicine-loaded polymeric nanomedicines: potential cancer therapeutics. In: Dutta P.K., Dutta J., eds. Multifaceted Development and Application of Biopolymers for Biology, Biomedicine and Nanotechnology. Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. p. :203-239.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differential cytotoxic effects of Annona squamosa seed extracts on human tumour cell lines: role of reactive oxygen species and glutathione. J Biosci. 2005;30(2):237-244.

- [Google Scholar]

- An insight into the cytotoxic activity of phytol at in vitro conditions. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2014;28(22):2053-2056.

- [Google Scholar]

- Annona Species. Southampton, UK: International Centre for Underutilised Crops; 2005.

- Effects of whole cigarette smoke on human gingival fibroblast adhesion, growth, and migration. J. Toxicol. Env. Heal. A. 2011;74(13):848-862.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-induced human asthmatic airway epithelial cell proliferation through an IL-13-dependent pathway. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.. 2010;125(4):844-850.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression and polymorphism of toll-like receptor 4 and effect on NF-κB mediated inflammation in colon cancer patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The curcumin analog (PAC) suppressed cell survival and induced apoptosis and autophagy in oral cancer cells. Sci. Rep. J.. 2021;11:11701.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simple protocol for using a LDH-based cytotoxicity assay to assess the effects of death and growth inhibition at the same time. PLoS One. 2011;6(11)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Annona species (Annonaceae): a rich source of potential antitumor agents? Ann. N Y Acad. Sci.. 2017;1398:30-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medicinal plants: a renewable resource for novel leads and drugs. In: Ramawat K.G., ed. Herbal Drugs: Ethnomedicine to Modern Medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2009. p. :1-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-79116-4_1

- [Google Scholar]

- Annona squamosa Linn: cytotoxic activity found in leaf extract against human tumor cell lines. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2014;27:1559-1563.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-vivo effect of the combination of tnf and adriamycin against a human breast cell-line expressing the mdr-phenotype. Int. J. Oncol.. 1995;7:1067-1072.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]