Translate this page into:

Cytochrome b lineages of Haemoproteus tinniculi in the endangered saker falcon (Falco cherrug) in Saudi Arabia

⁎Corresponding author. afrefaei@ksu.edu.sa (Abdulwahed Fahad Alrefaei)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Despite the ecological importance and social popularity of falcons, many elements of their biology remain unknown, including the variety of parasites that infect them in the wild and in captivity. Some of these are from the common alveolate genus Haemoproteus, which parasitise birds worldwide. We investigated the genetic diversity of Haemoproteus tinnunculi infecting the captive saker falcons (Falco cherrug) to describe their phylogenetic relationships. The overall prevalence of H. tinnunculi collected between December 2018 and February 2020 was 4.53% (58/1280). A fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene of H. tinnunculi was amplified from fifty-eight blood samples. Our findings indicate that two lineages of H. tinnunculi infect falcons in Saudi Arabia, one of which is reported here for the first time. These findings will inform the future investigation of phylogenetic relationships and genetic diversity of Haemoproteus parasites in falcons.

Keywords

Haemoproteus tinnunculi

Saker falcon

Cytochrome b gene

Genetic diversity

PCR

1 Introduction

Avian haemosporidian parasites are widely distributed across the globe. Three main genera, each consisting of numerous species, are recognised in birds: Haemoproteus, Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon (Atkinson and Van Riper III, 1991). They are transmitted by blood-sucking insects, including biting midges, louse flies, black flies and mosquitoes (Ritchie et al., 1994; Valkiunas, 2004). Haemoparasites are found in many raptors, and their incidence varies by host species and geography (Joseph, 1999). Because raptors are at the top of many food chains, their health can reflect the health of entire ecosystems (Cooper, 2002). Habitat loss and fragmentation have resulted in increased exposure of some raptor populations to parasitism, potentially altering host-parasite balances and increasing parasite pathogenicity.

While blood parasites are generally considered non-pathogenic, some evidence demonstrates that they can be harmful (Remple, 2004). Haemoparasites can cause increased thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TPP) levels, leucocytosis, anaemia and even death (Garvin et al., 2003; Redig, 2003). Haemoproteus spp. are the most common blood parasites in raptors (Garvin et al., 2003). Prolonged recuperation time and higher mortality rates are observed in captive raptors with haemoproteid infections (Shihab et al., 2013). During severe infection, clinical signs may include poor flight performance, reduced flight distance, inappetence, weight loss, acute anaemia, dyspnea and lethargy (Butterworth and Harcourt-Brown, 1996; Remple, 2004). Rahim, Bakhiet, and Hussein (2013) found that increased eosinophil count and splenic size were closely associated with haemoproteid infection in captive saker falcons.

From a conservation perspective, the diagnosis and treatment of avian haemosporidians are important for controlling their cumulative effects in raptors (Ciloglu et al., 2016). Nested cytochrome b polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis is widely used to detect avian haemosporidian parasites in the peripheral blood of infected birds (Bukauskaitė et al., 2015; Hellgren et al., 2004). This molecular diagnostic tool provides greater sensitivity and accuracy than traditional microscopic examination methods. Moreover, the technique has made possible the discovery of a wide diversity of parasites within the traditional morphospecies (Bensch et al., 2009). Despite the popularity of birds of prey, knowledge of their haemosporidian diversity is limited (Valkiunas, 2004), possibly attributable to the difficulty of capturing adult raptors in the wild (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2013). The avian haemosporidian Haemoproteus tinnunculi has been previously reported in captive falcons in Saudi Arabia using only traditional microscopic examination of blood smears (Naldo and Samour, 2004; Rahim et al., 2013). Only one previously published study included molecular analyses of Haemoproteus tinnunculi in captive falcons in Saudi Arabia (Alfaleh et al., 2020). However, the reported prevalence of H. tinnunculi was quite low (3%) compared to an earlier study based only on microscopic examination (Rahim et al., 2013), possibly due to the study’s relatively small sample size. From a total of 100 falcons examined, only three birds were found infected with H. tinnunculi. Thus, a larger-scale study of this haemoparasite is needed to improve our understanding of phylogenetic relationships and genetic diversity of avian haemosporidian parasites from captive falcons in Saudi Arabia and more generally, the Middle East.

This study aimed to examine the genetic diversity of Haemoproteus tinnunculi obtained from captive saker falcons (Falco cherrug) in Saudi Arabia via cytochrome b gene sequence analysis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Blood sample collection

Blood samples were obtained while the birds were under isoflurane anaesthesia. Blood (0.5 ml) was collected from the brachial vein of each bird using 1 ml disposable syringes and 23 gauge × 5/8 in. needles. After collection, the samples were transferred to pediatric blood collection tubes containing EDTA anticoagulant. Thin blood smears were prepared immediately after blood collection, directly from the tip of syringes, onto glass slides. The smears were air-dried and stained with modified Wright-Giemsa stain and examined microscopically for haemoparasites as described previously (Samour and Silvanose (2000). Diagnosis of Haemoproteus tinnunculi was confirmed by identifying the halter-shaped intraerythrocytic gametocytes partially encircling the nucleus, appearing pigmented and occupying more than 50% of the cytoplasm (Beynon et al., 1996). Birds were designated negative if no parasites were observed and positive (infected) if one or more parasites were identified. Blood samples from birds positive for infection were immediately stored at −20 °C for DNA extraction. “All procedures for the samples collection were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations by the Research Ethics Sub-Committee (REC) of the College of Sciences at the King Saud University (KSU) in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) (Ethics Reference No: KSU-SE-19-77)”.

2.2 DNA extraction for PCR

Total DNA was extracted from samples infected with Haemoproteus tinnunculi using DNAzol® (Invitrogen, Warrington, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 25 µl of blood samples were transferred to 1 ml Eppendorf tubes, then 500 µl of DNAzol was added, and the tubes were centrifuged at 10,000g for 3 min at 4 °C. After transferring the resulting supernatant to a new Eppendorf tube, 500 µl of absolute ethanol was added to each tube. The tubes were mixed by vortexing for 20 s, then centrifuged for 4 min at 10,000g and 3 °C. The resulting DNA pellet was washed with 100 µl of 75% ethanol, and samples were centrifuged again for two minutes. The DNA pellets were air-dried for 20 min before resuspension in 500 µl of distilled water. DNA concentrations of each sample were measured by spectrophotometry at 260 nm. The DNA extraction was visualised under UV light in a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

2.3 PCR amplification of the 16S rDNA

PCR amplification of the cytochrome b gene employed the following primers: HAEMF (5′ATGGTGCTTTCGATATATGCATG-3′) and HAEMR2 (5′GCATTATCTGGATGTGATAATGGT-3′), as described by Bensch et al. (2000). Each PCR reaction was run with 8.5 µl Green Master Mix (2X; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.5 µl (10 pg/µl) of each forward and reverse primer solution (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea), 8.5 µl of distilled water, and 1 µl of sample DNA (total volume 19 µl). Each amplification run included a negative control of purified water. The following cycle conditions were used for the PCR amplification: 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s then 72 °C for 45 s, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were visualised under UV light in 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Both DNA strands of all positive PCR products were sequenced by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea).

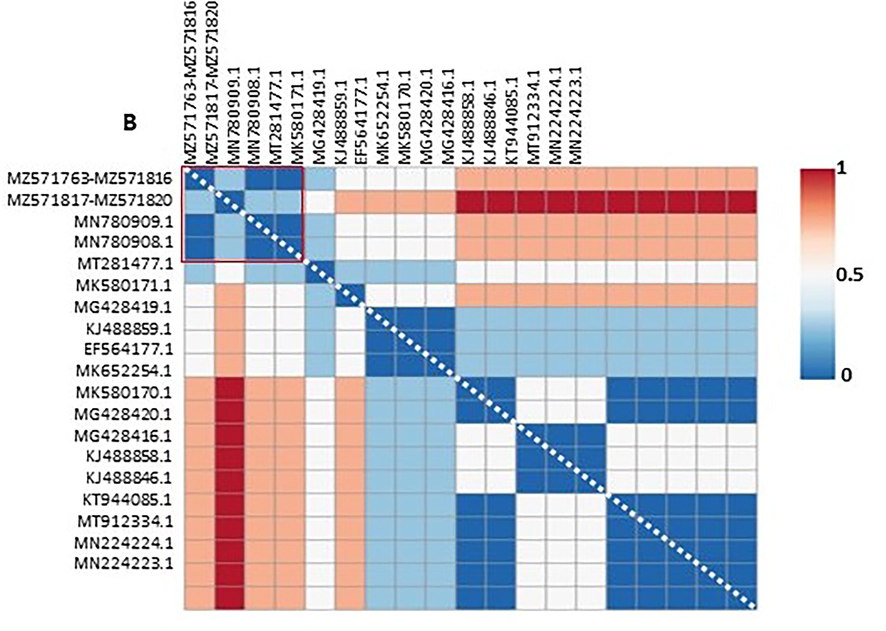

2.4 Sequence analysis and phylogenetic trees

All consensus sequences of the cytochrome b gene of the forward and reverse DNA strands were obtained and aligned by MEGA X software (Version 10.2.6; Kumar et al., 2018) to compare the evolutionary relationships among the sequences of Haemoproteus tinnunculi and build the phylogenetic tree. For cytochrome b gene comparisons, multiple reference sequences were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank database. The phylogenetic trees of the datasets available from GenBank and those found in this investigation were built by Maximum likelihood (ML) using genetic distance and the Tamura-Nei models, and nucleotide sequence analysis was utilised to examine the relationships between taxa (Jeanmougin et al., 1998; Kumar et al., 2016; Tamura and Nei, 1993). Variance estimation: bootstrap method. Number of bootstrap replications 10,000. The related taxa grouped in the bootstrap test are presented adjacent to the branches using Felsenstein’s bootstrap approachEstimates of Evolutionary Divergence between Sequences were calculated as genetic distance matrix (%). Genetic distance heatmap were ploted using CLUSTVIS web tool (Metsalu and Vilo, 2015).

3 Results

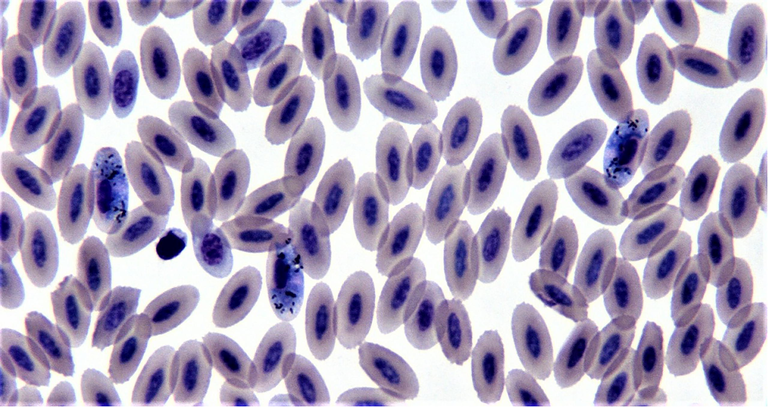

A total of 1280 blood samples were collected from captive saker falcons (Falco cherrug) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, between December 2018 and February 2020. Microscopic examinations showed that 58 (4.53%) samples were infected by Haemoproteus tinnunculi (Fig. 1). All samples that were positive by microscopy were also positive by PCR. Details of the falcon samples infected by H. tinnunculi is summarised in Table 1.

Haemoproteus tinnunculi gametocytes in blood smear from saker falcon (modified wright-giemsa stain).

Isolate ID

Case NO.

Host species

Location

Age

GeneBank Accession No.

1

R1

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571763

2

R2

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571764

3

R3

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571765

4

R4

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571766

5

R5

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571767

6

R6

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571768

7

R7

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571769

8

R8

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571770

9

R9

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571771

10

R10

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571772

11

R11

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571773

12

R12

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571774

13

R13

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571775

14

R14

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571776

15

R15

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571777

16

R16

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571778

17

R17

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571779

18

R18

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571780

19

R19

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571781

20

R20

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571782

21

R21

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571783

22

R22

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571784

23

R23

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571785

24

R24

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571786

25

R25

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571787

26

R26

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571788

27

R27

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571789

28

R28

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571790

29

R29

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571791

30

R30

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571792

31

R31

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571793

32

R32

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571794

33

R33

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571795

34

R34

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571796

35

R35

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571797

36

R36

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571798

37

R37

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571799

38

R38

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571800

39

R39

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571801

40

R40

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571802

41

R41

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571803

42

R42

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571804

43

R43

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571805

44

R44

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571806

45

R45

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571807

46

R46

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571808

47

R47

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571809

48

R48

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571810

49

R49

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571811

50

R50

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571812

51

R51

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571813

52

R52

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571814

53

R53

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571815

54

R54

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571816

55

R55

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571817

56

R56

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571818

57

R57

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571819

58

R58

Saker falcon

Riyadh

Adult

MZ571820

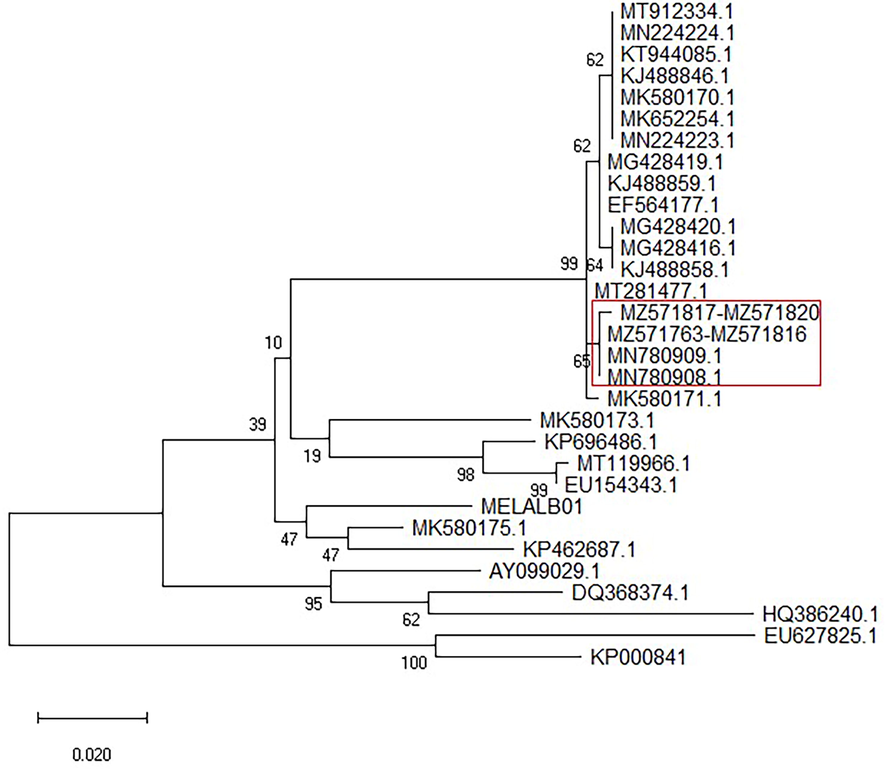

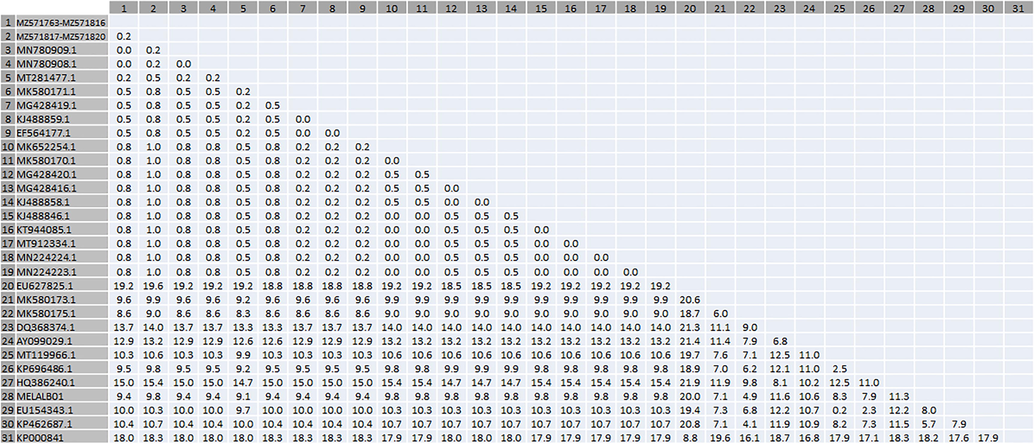

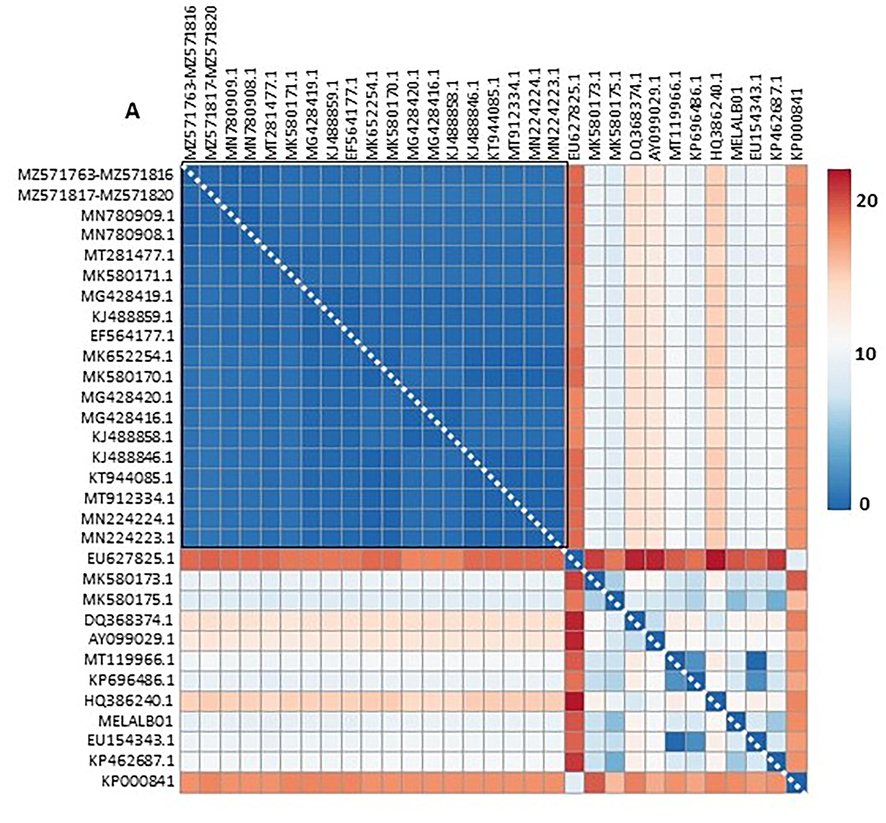

The sequenced PCR products from all samples were edited and aligned, and the resulting alignment of 406 bp was analysed. The ML tree (Fig. 2), genetic distance matrix and heatmap plot (Table 2 and Fig. 3 respectively) clustered them into one distinct group with high confidence. The genetic relationships among these sequences indicated two distinct lineages of H. tinnunculi. In 54 samples, the lineages were 100% matches to previously deposited lineages (NCBI accessions MN780909 and MN780908), and all sequences obtained were uploaded into GenBank (MT571763–M571816). We identified a new H. tinnunculi lineage in four falcons (MZ571817–-MZ571820). One sequence is reported here for the first time.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny of Haemoproteus tinnunculi. Phylogenetic tree was done using 406 bp of cytochrome b gene. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model (Tamura and Nei, 1993). The tree with the highest log likelihood (−1745.73) is shown. Tree is showed as traditional tree in straight view. Values at nodes represent bootstrap probabilities (bootstrap 10000). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018). The sequences used in constructing the tree were obtained from GenBank. Red rectangle: subgroup composed of accessions MN780909, MN780908, MT571763-M571816 and MZ571817-MZ571820.

Genetic distance (%) heatmap. Data from Table 2 were ploted as a heatmap using CLUSTVIS web tool (Metsalu and Vilo, 2015). A) Genetic distance of 31 accession. Red square: subgroup of 19 accessions re-plottered in B. B) Genetic distance of 19 accession. Red square: subgroup composed of accessions MN780909, MN780908, MT571763-M571816 and MZ571817-MZ571820.

Genetic distance (%) heatmap. Data from Table 2 were ploted as a heatmap using CLUSTVIS web tool (Metsalu and Vilo, 2015). A) Genetic distance of 31 accession. Red square: subgroup of 19 accessions re-plottered in B. B) Genetic distance of 19 accession. Red square: subgroup composed of accessions MN780909, MN780908, MT571763-M571816 and MZ571817-MZ571820.

4 Discussion

In this study, cytochrome b gene was used to compare the genetic variation of Haemoproteus tinnunculi that was collected from captive saker falcons in Saudi Arabia. We found a new lineage of H. tinnunculi that is capable of infecting falcons in Saudi Arabia. This data is crucial for providing a better understanding of the genetic variation of falcon parasites their phylogenetic relationships.

The cytochrome b gene is one of the most common markers used for molecular detection and genetic characterisation of avian haemosporidians (Staffan Bensch et al., 2009; Sehgal, 2015; Valkiūnas et al., 2020). Parallel analyses of mtDNA cytochrome b provide the best evidence for species lineages, demonstrating consistent gene-trees and apparent absence of recombination for several closely related lineages (Bensch et al., 2004; Hellgren et al., 2007; Pérez-Tris et al., 2007). We revealed two distinct lineages of H. tinnunculi in saker falcons based on cytochrome b analysis. One of these lineages had not been previously registered in GenBank. The cytochrome b gene was shown to be useful in building well-supported phylogenies for H. tinnunculi species.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed two distinct sequences that were clearly split into multiple branches depending on the cytochrome b gene (Fig. 1). Sequence alignment indicated that 54 H. tinnunculi samples were 100% identical to a previously identified H. tinnunculi sequence (GenBank MN780909) found in a saker falcon in Saudi Arabia (Alfaleh et al., 2020). One new detected lineage was found in four falcons, which had not been described previously. This sequence shared 99.75% identity with previously sequenced H. tinnunculi (GenBank MN780908) (Alfaleh et al., 2020).

Haemoproteus parasites are well-known avian haematozoa that can cause decreased productivity and increased mortality in birds (Elahi et al., 2014). Blood-sucking dipteran insects transmit avian haemoproteids (Friend et al., 1999; Ritchie et al., 1994; Valkiunas, 2004). Microscopic examination of a Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smear is usually used to diagnose Haemoproteus infection. Although the parasites resemble Plasmodium, the pigment inside the intra-erythrocytic gametocytes is more scattered, and there are no schizonts visible in peripheral blood smears. The pigment granules are formed by the digestion of haemoglobin in the host’s RBCs and appear as refractile yellow to brown granules inside the RBCs (Friend et al., 1999). Haemoproteus tinnunculi was the most prevalent hematozoan parasite found in captive falcons in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East ((Naldo and Samour, 2004; Samour and Silvanose, 2000). According to Rahim et al. (2013), haemoproteid infection is more common at the end of the winter season, which lasts from January to April and usually coincides with the rainy season; this could be due to increased density and activity of Culicoides spp. and other biting insects that could serve as vectors for Haemoproteus spp. Molecular detection of H. tinnunculi has included extracted DNA amplification by PCR as an extremely sensitive and specific tool for avian haemosporidians. However, there is no common naming of lineages, thus making it difficult to find and compare information (Valkiūnas et al., 2019). There have been minimal molecular investigation of H. tinnunculi in falcons. Although a smear-based diagnosis is necessary, it is often inadequate or inaccurate in identifying and diagnosing Haemoproteus species (Ortiz-Catedral et al., 2019; Valkiūnas et al., 2020). Previous investigations have shown that PCR has a comparably high sensitivity to microscopy in diagnosing avian Haemoproteus (Tavassoli et al., 2018; Valkiūnas et al., 2019).

In this study, we only examined H. tinnunculi that infected saker falcons. Rahim et al. (2013) and Alfaleh et al. (2020) reported that this falcon species experienced a greater risk of infection with H. tinnunculi. This species has also been reported in peregrine falcons (F. peregrinus) and gyrfalcons (F. rusticolus) in Kuwait and F. sparverius from Pennsylvania, USA (Apanius and Kirkpatrick, 1988; Tarello, 2007). These results indicate that F. cherrug may experience greater exposure than other falcons or that there are host species variations in H. tinnunculi infection. Meixell et al. (2016) reported that several variables, including vector exposure, host body size (a larger size possibly attracting more insects), and plumage color may influence host-specific vectors. Further analyses of genetic diversity of haemoproteid parasites and exploration of relevant clinical and subclinical effects and possible pathogenicity in other falcon species are needed.

Valkiūnas et al. (2019) established the first genetic markers for identifying haemoproteids parasitising falconiform birds overwintering in Africa. They described three new Haemoproteus species using morphological and molecular markers. Phylogenetic study of haemoproteid lineages obtained from falcons, as well as available morphological data, show that H. tinnunculi and H. brachiatus have similar cytochrome b gene sequences.

This study will be valuable for researchers interested in the evolutionary history of H. tinnunculi parasites and to falconry managers, clinicians, and microbiologists. Our results will inform avian ecology and contribute to the study of an important molecular toolbox in examining a disease of increasing importance.

Acknowledgments

We extend our appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project (RSP-2021/218), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and we thank the Falcon Medical and Research Hospital of the Fahad bin Sultan Falcon Center in Riyadh for assistance with samples provision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Prevalence and molecular characterization of Haemoproteus tinnunculi from falcons in Saudi Arabia. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res.. 2020;7(4):626.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary report of Haemoproteus tinnunculi infection in a breeding population of American kestrels (Falco sparverius) J. Wildl. Dis.. 1988;24(1):150-153.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, C.T., and Van Riper III, C., 1991. Pathogenecity and epizootiology of avian hematozoa: Plasmodium, Leucocytozoon, and Haemoproteus. Bird-parasite interactions. Ecology, evolution, and behavior, JL Loye and M. Zuk (eds.). Oxford University Press, New York, 20-48.

- MalAvi: a public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Mol. Ecol. Resour.. 2009;9(5):1353-1358.

- [Google Scholar]

- Linkage between nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences in avian malaria parasites: multiple cases of cryptic speciation? Evolution. 2004;58(7):1617-1621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Host specificity in avian blood parasites: a study of Plasmodium and Haemoproteus mitochondrial DNA amplified from birds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci.. 2000;267(1452):1583-1589.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beynon, P.H., Forbes, N.A., Harcourt-Brown, N.H., 1996. BSAVA manual of raptors, pigeons and waterfowl: British Small Animal Veterinary Association Ltd.

- Biting midges (Culicoides, Diptera) transmit Haemoproteus parasites of owls: evidence from sporogony and molecular phylogeny. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neonate husbandry and related diseases. Manual of raptors, pigeons and waterfowl 1996:216-223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of avian haemosporidian parasites from raptor birds in Turkey, with molecular characterisation and microscopic confirmation. Folia Parasitol.. 2016;63:1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J.E., 2002. Methods of investigation and treatment. Birds of prey: health and disease, 3rd Ed. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, United Kingdom, 28-70.

- Prevalence and Diversity of Avian Haematozoan Parasites in Wetlands of Bangladesh. J. Parasitol. Res.. 2014;2014:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Friend, M., Franson, J.C., Ciganovich, E.A., 1999. Field manual of wildlife diseases: general field procedures and diseases of birds: US Geological Survey.

- Pathogenicity of Haemoproteus danilewskyi, Kruse, 1890, in blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata) J. Wildl. Dis.. 2003;39(1):161-169.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diversity and phylogeny of mitochondrial cytochrome B lineages from six morphospecies of avian Haemoproteus (Haemosporida: Haemoproteidae) J. Parasitol.. 2007;93(4):889-896.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new PCR assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avian blood. J. Parasitol.. 2004;90(4):797-802.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci.. 1998;23(10):403-405.

- [Google Scholar]

- Raptor hematology and chemistry evaluation. Vet. Clin. North Am.: Exot. Anim. Pract.. 1999;2(3):689-699.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., Tamura, K., 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35(6), 1547.

- MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2016;33(7):1870-1874.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection, prevalence, and transmission of avian hematozoa in waterfowl at the Arctic/sub-Arctic interface: co-infections, viral interactions, and sources of variation. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9(1):1-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2015;43(W1):W566-W570.

- [Google Scholar]

- Causes of morbidity and mortality in falcons in Saudi Arabia. J. Avian Med. Surg.. 2004;18(4):229-241.

- [Google Scholar]

- Haemoproteus minutus is highly virulent for Australasian and South American parrots. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular characterization of haemosporidian parasites from kites of the genus Milvus (Aves: Accipitridae) Int. J. Parasitol.. 2013;43(5):381-387.

- [Google Scholar]

- Haemoproteus tinnunculi infection in captive saker falcons (Falco cherrug) in Saudi Arabia. Comp. Clin. Pathol.. 2013;22(6):1255-1258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Falconiformes (vultures, hawks, falcons, secretary bird). Zoo and wild animal medicine (5th Ed.). St Louis, MI USA: Elsevier; 2003. p. :150-160.

- Intracellular hematozoa of raptors: a review and update. J. Avian Med. Surg.. 2004;18(2):75-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avian medicine: principles and application. Lake Worth, FL: Wingers Publ. Inc.; 1994.

- Parasitological findings in captive falcons in the United Arab Emirates. In: Lake Worth F.L., ed. Raptor Biomedicine III. Zoological Education Network Inc; 2000. p. :117-124.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manifold habitat effects on the prevalence and diversity of avian blood parasites. Int. J. Parasitol.: Parasites Wildlife. 2015;4(3):421-430.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predicting the functional, molecular, and phenotypic consequences of amino acid substitutions using hidden Markov models. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(1):57-65.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 1993;10(3):512-526.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical signs and response to primaquine in falcons with Haemoproteus tinnunculi infection. Vet. Rec.. 2007;161(6):204-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- PCR-RFLP detection of Haemoproteus spp. (Haemosporida: Haemoproteidae) in pigeon blood samples from Iran. Bulg. J. Vet. Med.. 2018;21(4):429-435.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avian malaria parasites and other haemosporidia. CRC Press; 2004.

- Molecular characterization of six widespread avian haemoproteids, with description of three new Haemoproteus species. Acta Trop.. 2019;197:105051.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular characterization of swallow haemoproteids, with description of one new Haemoproteus species. Acta Trop.. 2020;207:105486.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]