Translate this page into:

Corneal ulcer/keratitis derived Aspergillus flavus & Aspergillus tamarii and their RAPD-PCR typing

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Majmaah University, Al Majmaah 11952, Saudi Arabia. m.palanisamy@mu.edu.sa (Palanisamy Manikandan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The aim of the study was investigate the DNA polymorphisms of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus tamarii isolated from regional fungal keratitis cases based on random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analyses. Thirty-two A. flavus and six A. tamarii isolates were identified using conventional macroscopic and microscopic features. Five decamer primers were used to amplify the genomic DNA sequences of the test isolates, and 140 total RAPD patterns were generated among them. From each of the 38 isolates, a range of 15–30 RAPD types were revealed. All of these were isolated from male farmers from Tamil Nadu. In the future, RAPD analyses could be employed as a reliable and rapid technique to differentiate among keratitis isolates of fungal pathogens.

Keywords

RAPD PCR

Eye infection

Aspergillus flavus

Corneal ulcer

Molecular typing

Keratitis

1 Introduction

Fungal keratitis is a leading cause of blindness among agricultural workers in India, and Fusarium and Aspergillus species are the most common etiological agents (Homa et al., 2013; Kredics et al., 2015; Manikandan et al., 2008a). Studies of keratomycosis-derived Aspergillus strains have been based on microscopy and culture at the genus level, as phenotypic methods report only a moderate level of differentiation among A. flavus strains (Rath, 2001). However, molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) provide a prompt, accurate diagnosis compared to culture-based morphological identification (Baranyi et al., 2013; Kredics et al., 2007; Manikandan et al., 2008b). Additionally, molecular studies re-identify certain pathogenic isolates reported as ‘others’ by routine methods (Baranyi et al., 2013; Kredics et al., 2008, 2009; Manikandan et al., 2008b). Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis is a reliable PCR-based diagnostic tool that can differentiate clonal fungal lineages and has been used to elucidate variability within and between species, including many Fusarium species (Carter et al., 2002). Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (James et al., 2000; Moody and Tyler, 1990), RAPD (Heinemann et al., 2004; Rath, 2001), and microsatellite polymorphism analyses (Guarro et al., 2005) have been widely used for typing A. flavus isolates. However, the RAPD assay resulted in the most reliable differentiation among Aspergillus species (A. flavus, A. fumigatus, A. niger, and A. nidulans) and therefore, could become a common molecular method for identification and differentiation (Anderson et al., 1996; Aufauvre-Brown et al., 1992; Leenders et al., 1999; Lin et al., 1995; Loudon et al., 1993). However, there are only a limited number of studies available on the molecular characterization of Aspergillus species, especially on strains isolated from ocular infections and their epidemiological relatedness. This study was carried out to ascertain the DNA polymorphisms of mycotic keratitis-derived Aspergillus isolates based on random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analyses.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection of specimens and identification of strains

This study investigated fungal filaments derived from corneal tissue scrapings based on microscopic examination (10% KOH wet mount and Gram staining) and inoculation on 5% sheep blood agar, chocolate agar, and potato dextrose agar. Confirmed fungal growth on the test culture media was further processed for species identification based on standard culture techniques. The identified isolates were stored in 0.85% saline at 4 °C until further processing.

2.2 Cultivation and harvesting of Aspergillus species

The Aspergillus isolates were cultivated individually in 20 ml of yeast extract-peptone-dextrose media in Erlenmeyer flasks for two days at 25 °C on a rotary shaker (120–150 rpm) and harvested from 10 ml culture through vacuum filtration. The harvested mycelia were rinsed with several volumes of 0.1 M MgCl2 and were thoroughly dried under vacuum. The dried material was transferred to a chilled mortar, ground to a powder, mixed with liquid N2, and the processed fungal material was stored at −20 °C for further cell wall lysis.

2.3 Extraction and isolation of Aspergillus DNA

Each test Aspergillus isolate was grown on a suitable medium, and their DNA was extracted and prepared for PCR according to Kredics et al. (2009) and Manikandan et al. (2008b, 2010). In detail, the samples stored at −20 °C underwent the following procedure: cell lysis solution (300 μl) was added to each fungal sample, the cells were suspended by vortex mixing, and the samples were incubated at 65 °C for 15 min then cooled on ice for 5 min. Subsequently, protein precipitation reagent (150 μl) was added and the sample was vortexed for 10 s, followed by micro-centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh microfuge tube, and 500 μl of isopropanol were added and mixed thoroughly by inversion. The sample was micro-centrifuged again at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet containing the DNA was washed with 0.5 ml of 70% ethanol and air dried. Finally, the pellet was suspended in 50 μl of TE buffer. Suspected RNA contamination was removed using 1 μl of 5 μg/μl RNase A. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, confirmed on an agarose gel, and the pure DNA was stored at 4 °C.

2.4 RAPD analyses of Aspergillus isolates

The purified DNA of the Aspergillus strains was amplified randomly, the products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the patterns were analyzed to screen diversity. RAPD-PCR reactions of the test DNA samples were performed in 25 μl reaction mixtures as described by Williams et al. (1990). The five decamer primers (Operon random primer kit, Operon Technology, Germany) used to amplify the fungal DNA sequences were A01: 5′-CAGGCCCTTC-3′, E17: 5′-CTACTGCCGT-3′, G19: 5′-GTCAGGGCAA-3′, K16: 5′-CCCAGCTGTG-3′, and R15: 5′-GGACAACGAG-3′.

The prepared mixture was amplified in an MJ Mini Personal thermal cycler model PTC 1148 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) using the following cycling conditions: initialization at 94 °C for 2 min, denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 36 °C for 1 min, and elongation for 1.5 min at 72 °C. From the denaturation step, the cycle was repeated 35 times, with a final elongation for 3 min at 72 °C and final hold at 4 °C. The PCR products underwent electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide and documented under ultraviolet light (GelDoc 2000; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The DNA banding patterns were interpreted using gel analyzing software. Based on the banding patterns with at least 90% homology, highly related groups were defined.

3 Results

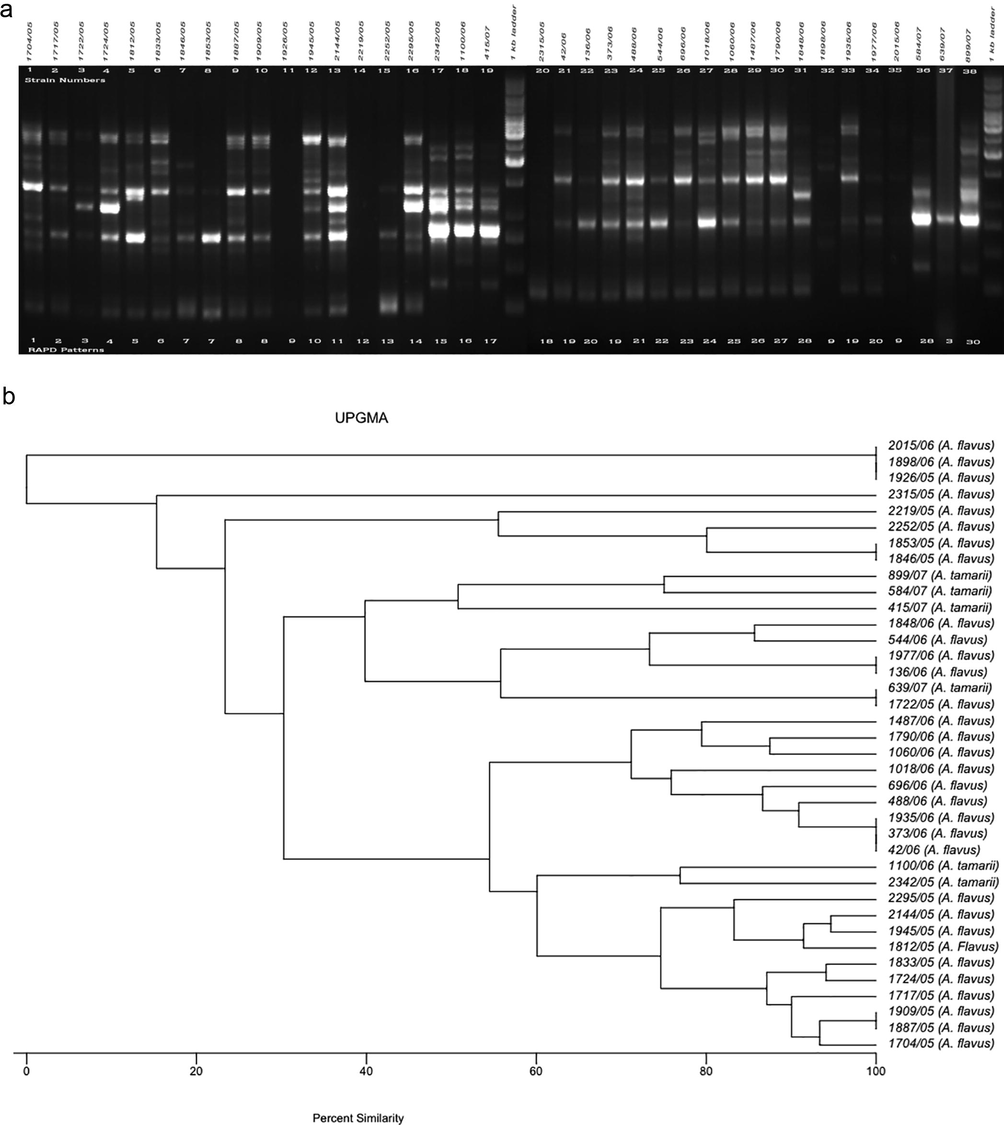

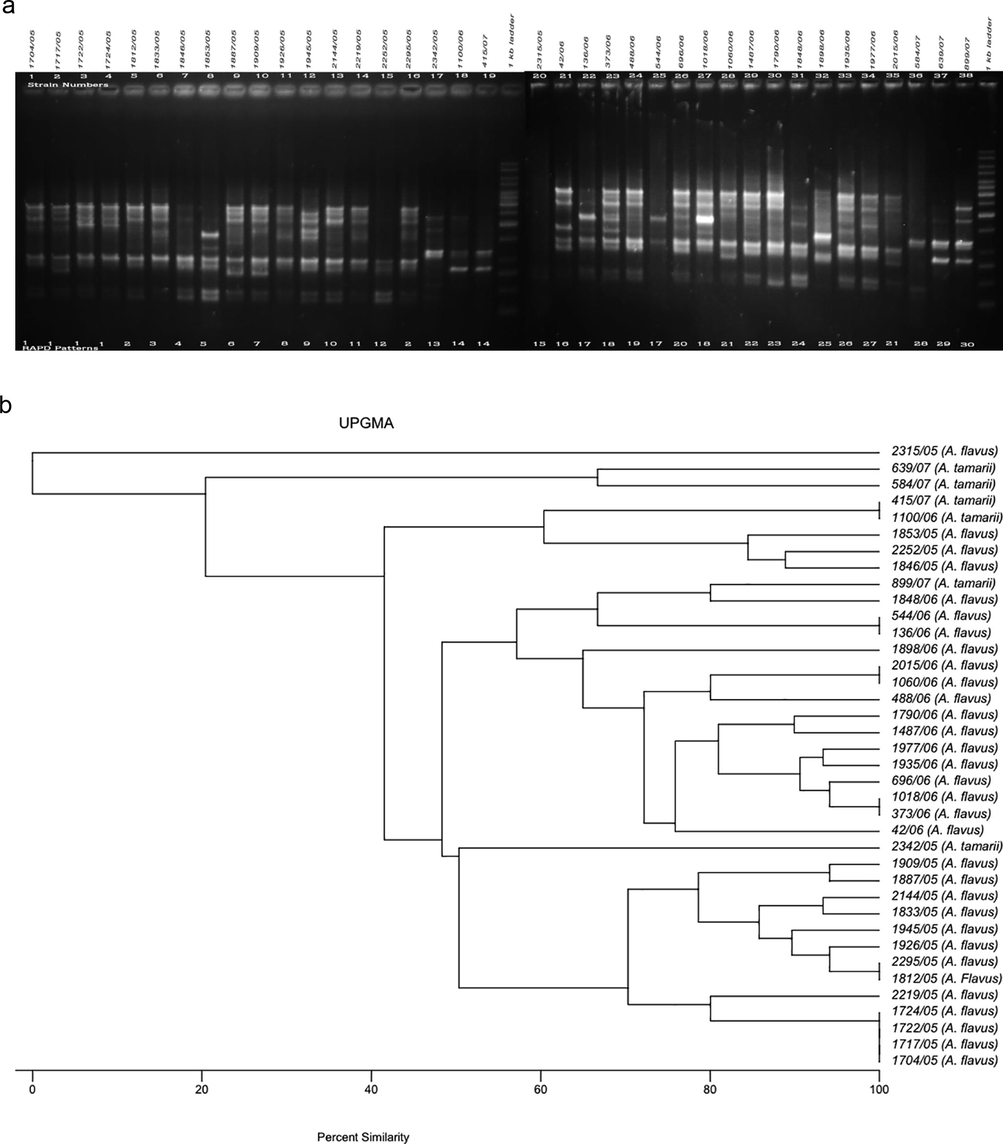

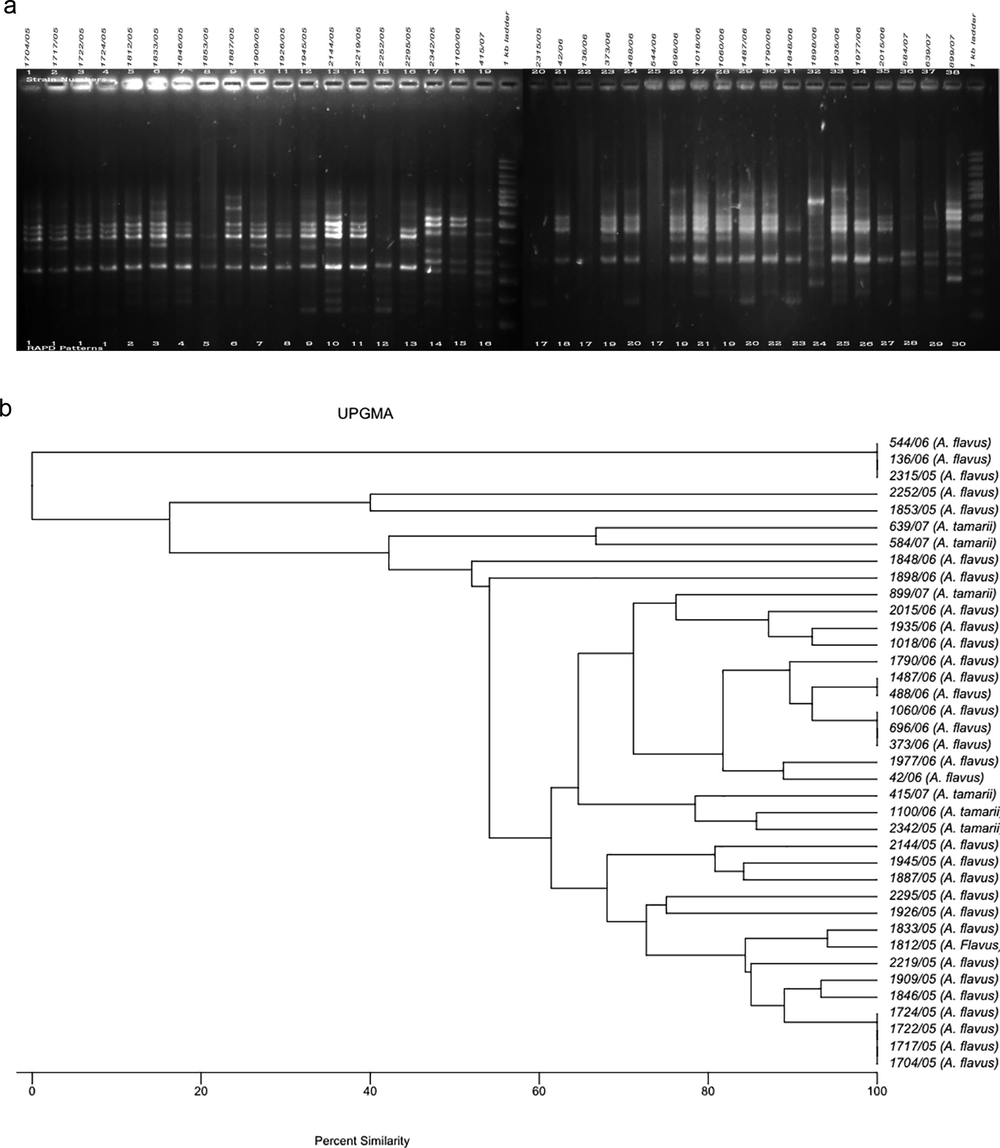

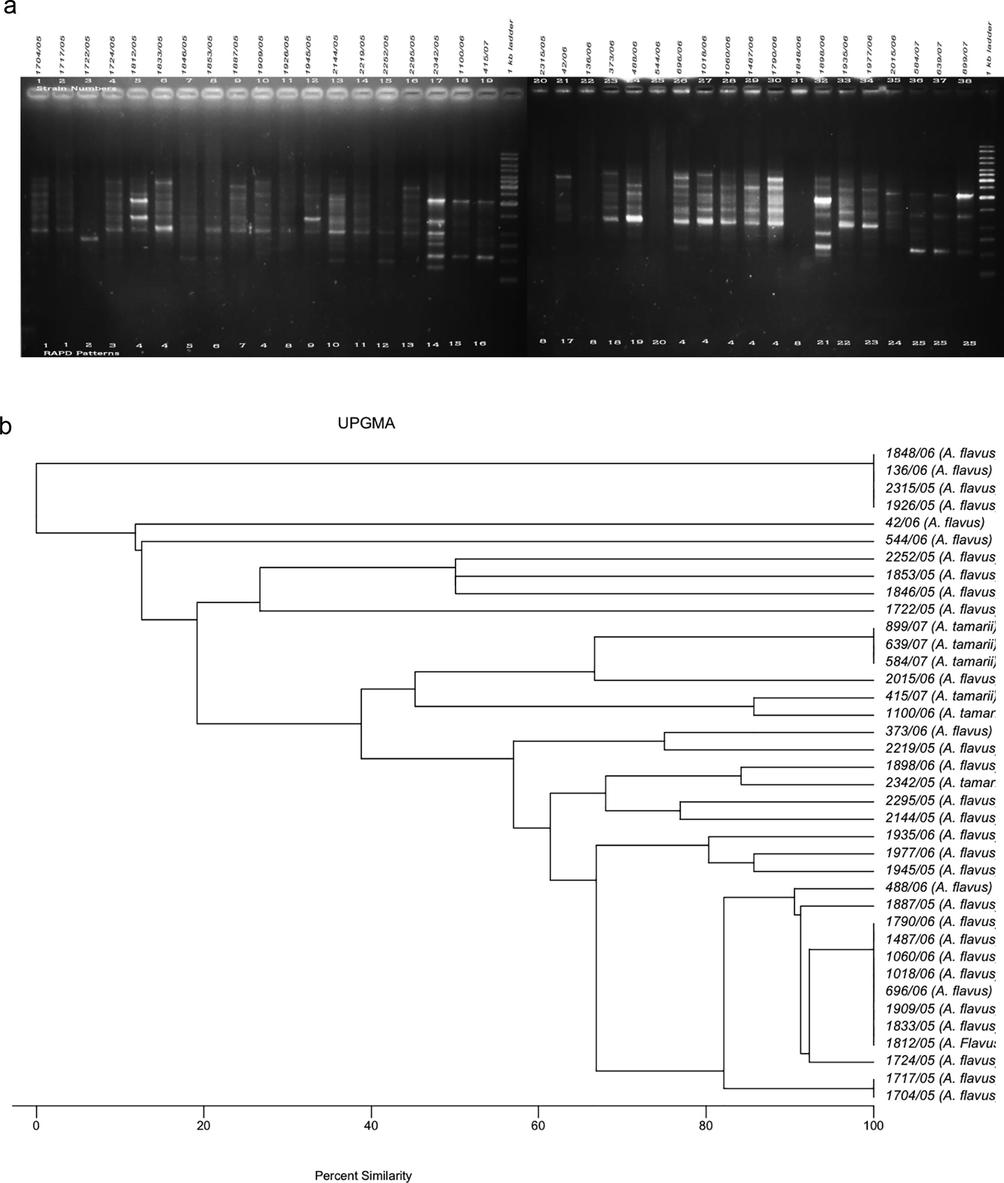

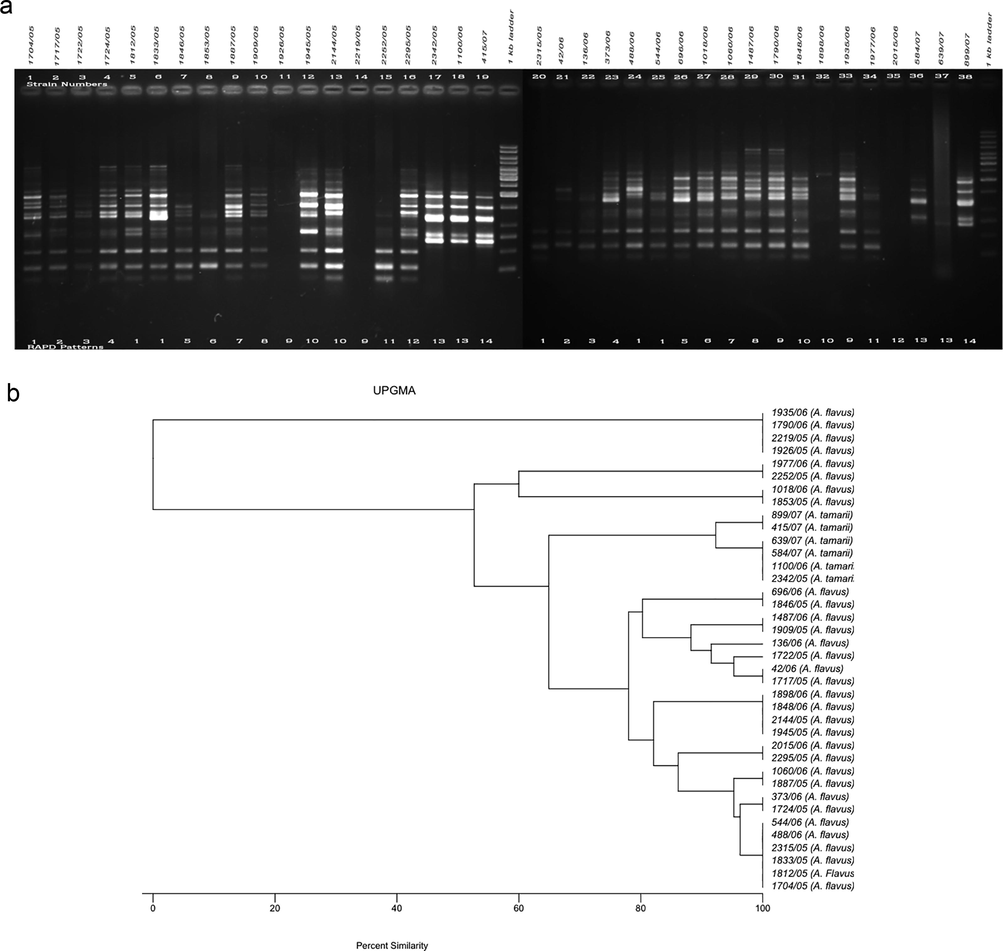

The RAPD method was used to determine variability among the test A. flavus (n = 32) and A. tamarii (n = 6) isolates based on total DNA polymorphisms to determine the clonality of each aspergillus. The amplified DNA polymorphisms, shown as banding patterns, and the cluster analyses based on the percentage similarity among the RAPD patterns produced by the five decamer primers are depicted in Figs. 1–5. In each figure, lanes 1–19 and 20–38 represent the RAPD patterns of the isolates, and the remaining two lanes [median and flanking (right)] include the 1 kb marker ladder (250–5000 bp). Each unique pattern was categorized as a RAPD type comprising one or more isolates for the five primers individually. A total of 140 RAPD patterns were generated among the 38 strains; a range of 15–30 RAPD types were revealed among at least 30 isolates. Amplification with primers A01, G19, and K16 resulted in 30 different RAPD patterns each, whereas amplification with primers R15 and E17 yielded 25 and 15 different patterns, respectively.

a. RAPD PCR amplification patterns of A. flavus and A. tamarii strains, amplicons of A01 primer; b. UPGMA-based dendrogram showing the percentage similarity among the A01 primer-based RAPD patterns of aspergilli.

a. RAPD PCR amplification patterns of A. flavus and A. tamarii strains, amplicons of G19 primer; b. UPGMA-based dendrogram showing the percentage similarity among the G19 primer-based RAPD patterns of aspergilli.

a. RAPD PCR amplification patterns of A. flavus and A. tamarii strains, amplicons of K16 primer; b. UPGMA-based dendrogram showing the percentage similarity among the K16 primer based RAPD patterns of aspergilli.

a. RAPD PCR amplification patterns of A. flavus and A. tamarii strains, amplicons of R15 primer; b. UPGMA-based dendrogram showing the percentage similarity among the R15 primer-based RAPD patterns of aspergilli.

a. RAPD PCR amplification patterns of A. flavus and A. tamarii strains, amplicons of E17 primer; b. UPGMA-based dendrogram showing the percentage similarity among the E17 primer-based RAPD patterns of aspergilli.

3.1 RAPD analyses of aspergilli using the A01 primer

When the DNA of the test isolates was amplified, primer A01 yielded zero (isolates 1926/05, 1898/06, and 2015/06) to 10 (strain 2144/05) bands, with an average of five; the band sizes ranged from ∼250 to 4000 bp. Of the 30 RAPD patterns differentiated by this primer, six patterns were represented by more than one isolate. UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) analyses confirmed 100% similarity among each of these six patterns. In particular, RAPD types 9 and 19 were represented by three isolates and RAPD types 3, 7, 8, and 20 were included by two strains each.

The RAPD types and UPGMA-based percentage similarity among the Aspergillus isolates are shown in Fig. 1a and b, respectively. All strains with RAPD types 9 and 19 were from male ocular patients in the Indian state Tamil Nadu.

3.2 RAPD analyses of aspergilli using the G19 primer

All 38 isolates of A. flavus were amplified by the G19 primer (except 2315/05), which yielded a maximum of 12 bands (strain 1487/06). The average number of bands was six and the size of the bands ranged between ∼300 and 3000 bp. Fig. 2a and b respectively show the RAPD types and the UPGMA-based percentage similarity among the RAPD patterns of A. flavus. Thirty RAPD types were produced, of which six types (1, 2, 14, 17, 18, 21) included more than one isolate. Four isolates were categorized as RAPD type 1 and were isolated from Tamil Nadu male farmers in 2005. Similarly, the two isolates (544/06 and 136/06) of RAPD pattern 17 were obtained from the Indian state Kerala and were from males involved in agricultural activities.

3.3 RAPD analyses of aspergilli using the K16 primer

The test DNA of three A. flavus isolates was not amplified completely with the K16 primer; the band size for the remaining strains ranged between ∼250 and 4000 bp with a maximum of 14 bands (strain 2144/05) (Fig. 3). Overall, the K16 primer categorized the 38 strains into 30 RAPD types. K16 yielded a pattern similar to the G19 primer for the isolates 1704/05, 1717/05, 1722/05, and 1724/05, which were categorized as RAPD type 1 by both primers. The K16-based RAPD type 17 was represented by three isolates 544/06, 136/06 and 2315/06, of which the first two isolates were also clustered as RAPD type 17 by primer G19. Strain 2315/06 was from a male farmer in Tamil Nadu, similar to isolates 544/06 and 136/06.

3.4 RAPD analyses of aspergilli using the R15 primer

The 38 A. flavus isolates were grouped into 25 RAPD types based on the R15 primer (band size ranged from ∼400 to 4000 bp) (Fig. 4). The DNA of four test isolates (2315/05, 1926/05, 1848/06, and 136/06) was not amplified by the primer and were designated RAPD type 8. The DNA of strains 2315/05 and 1926/05 was also not amplified by the primers A01 or E17 and G19 or K16, respectively. RAPD types 4, 8, and 25 each made a cluster represented by more than one aspergillus with eight, four, and three isolates, respectively. The four isolates (1704/05, 1717/05, 1722/05, and 1724/05) representing RAPD type 1 with the primers G19 and K16 could in turn be differentiated by the R15 primer and the isolates 1722/05 and 1724/05 were separated into RAPD type 2 and RAPD type 3, respectively.

3.5 RAPD analyses of aspergilli using E17 primer

The E17 primer generated a maximum of 14 bands among test A. flavus isolates and the sizes ranged from ∼100 to 5000 bp. However, no amplification was recorded among the four isolates 1026/05, 2219/05, 2315/05 and 2015/06 (Fig. 5a). The UPGMA-based analyses of the percentage similarity tree showed a total of 15 groups among the test isolates (Fig. 5b).

4 Discussion

Utilization of molecular techniques such as RAPD, amplified fragments length polymorphism, RFLP, or DNA sequence analyses are justifiable for taxonomic and phylogenetic studies of fungal species due to their reliability (Dwivedi et al., 2018). Accurate species identification within the A. flavus complex has remained difficult due to overlapping morphological and biochemical characteristics (Hedayati et al., 2007). Various molecular approaches have been used for the detection of Aspergillus from environmental and clinical samples. Rath (2001) studied the phenotypical similarities among A. flavus strains and determined only a moderate sensitivity to differentiate their isolates. However, RFLP (James et al., 2000; Moody and Tyler, 1990), RAPD (Heinemann et al., 2004), and microsatellite polymorphism analysis (Guarro et al., 2005) are the most widely used typing methods. The RAPD assay showed the most discriminatory power among all Aspergillus species (A. flavus, A. fumigatus, A. niger, and A. nidulans) investigated (Rath, 2001). Combining these molecular techniques with initial morphological identifications could result in more reliable identification of clinical fungal isolates.

In this study, the genetic variation among Aspergillus isolates from fungal keratitis was evaluated based on RAPD analyses alongside conventional microbiological methods. A total of 38 isolates were amplified through PCR with five primer sets, and for each primer at least one of the test isolates was not amplified. In particular, the DNA of isolate 1926/05 could not be amplified by AO1, O17, and R15, and 2315/05 by G19, K16, and R15. The successfully amplified isolates were grouped into RAPD patterns based on DNA banding patterns and differentiated. A majority of the isolates had varying RAPD patterns and were categorized as unique. The E17 primer grouped the 38 isolates into 15 RAPD patterns, except the isolate 1722/05 which had a unique pattern. Similarly, Diaz-Guerra et al. (2000) evaluated the reliability of RAPD among eight unrelated control strains of A. flavus and the strains represented eight different genotypes. Though Buffington et al. (1994) and James et al. (2000) investigated the consistency of restriction endonuclease analyses of total cellular DNA for any variation, Hedayati et al. (2007) had described that RFLP along with Southern blotting could be impractical for frequent analyses. On the other hand, though reproducibility was a primary concern of RAPD, the method was reported to be widely applied in many studies (Hedayati et al., 2007). However, the E17 primer applied in this study distinguished all six isolates of A. tamarii from A. flavus into two separate groups (group 1: 899/07, 415/07; group 2: 639/07, 584/07, 1100/06, 2342/05). In our experience, for many years, all of the A. tamarii strains have been reported as A. flavus due to their morphological similarities. Our recent molecular studies and their outcomes have extended our understanding about accurate species identification of fungi that have been isolated from fungal corneal ulcers. Tam et al. (2014) described similar issues of misidentification of A. tamrii and A. nomius as A. flavus using other molecular techniques.

Researchers have employed other molecular tools for fungal species identification; Buffington et al. (1994) studied the products of a test strain of A. flavus from RAPD and RFLP analyses to produce a DNA probe for Southern blot analysis. De Valk et al. (2005) demonstrated typing sensibility of microsatellites based on the extensive polymorphisms among A. fumigatus. Guarro et al. (2005) studied randomly amplified microsatellites to standard strains of A. flavus and A. fumigatus isolated from an assumed outbreak. They described that the technique was useful for distinguishing Aspergillus species. In this line, Leenders et al. (1999) studied the dynamic nature of RAPD fingerprinting to determine the cause of an outbreak of invasive aspergillosis.

Brandt et al. (1998) evaluated the utility of RAPD-PCR and the TaqMan assay in identifying A. fumigatus, and the diagnostic assay was reported to be a scientific approach for identifying and detecting DNA targets with no requirement for prior test DNA sequence information. Also, RAPD-PCR allowed diagnostic information to be readily obtained even for fungal species with no previous molecular identification. Einsele et al. (1997) detected Aspergillus DNA from blood approximately four days before the appearance of pulmonary infiltrates consistent with fungi by computed tomography scan in patients with presumed aspergillosis.

Leenders et al. (1999) studied the RAPD patterns among clinical and environmental isolates of Aspergillus spp. and demonstrated that all of the clinical isolates of A. flavus appeared to be genetically different. However, they also stated that the environmental and nosocomial isolates could not be differentiated, and all of the strains appeared to be a specific genotype. In this study, the R15 primer grouped three A. tamarii isolates together, while the other three remained individuals. The G19 primer grouped two A. tamarii strains while the rest did not form groups. These primers were able to distinguish A. tamarii from A. flavus strains. However, unlike E17, they did not form a single group. Balajee et al. (2006) screened 50 test isolates of A. fumigatus from invasive aspergillosis using PCR-RFLP of the benA and rodA genes, that had previously been identified morphologically, and predicted 16 isolates as non-A. fumigatus. Similarly, the use of PCR without additional techniques in the diagnosis/discrimination of fungal endophthalmitis over other forms of endophthalmitis was evaluated by Anand et al. (2001). They reported that although the method could not identify fungi to the genus and species level, it was shown to be more sensitive in diagnosing a generic fungal infection compared to conventional mycological methods and therefore could justify the use of antifungal therapy before identification to the species level. Jaeger et al. (2000) developed a nested PCR method for the detection of three fungal species (A. fumigatus, Candida albicans, and Fusarium solani) from ocular samples. A similar strategy was used to establish a detection system for A. fumigatus, C. albicans, and F. oxysporum from corneal scrapings of keratitis patients by Gaudio et al. (2002). Kumar and Shukla (2005) successfully detected fungal keratitis caused by A. fumigatus based on single-stranded conformation polymorphism analysis of sequence variation in different regions of rRNA genes. It could be concluded that the relevance of the RAPD tool for the typing of pathogenic aspergilli has been reported to be both effective as well as unproductive.

However, the RAPD-based assay as presented here confirmed a significant polymorphism among the test keratitis isolates of A. flavus and A. tamarii, and hence could be extended to evaluate various other clinically significant species of Aspergillus.

5 Conclusion

The present study assessed the usability of RAPD assay as an effective genome analysis method and concluded that polymorphisms among fungal isolates could be brought out.

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to thank Deanship of Scientific Research at Majmaah University, Al Majmaah, 11952, Saudi Arabia for supporting this work under the Project Number R-1441-77.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, PM, SK, LK and CV; methodology, PM, SK, BA, AA, VR and AAB; validation, PM, BA, MA, SB, RA and SA; formal analysis, AA, KP, CSS; investigation, BA, P.M, SK, CSS and KP; resources, PM, KP, CSS, SK, LK and CV; data curation, PM, BA, KP, CSS, SK and LK; writing – original draft preparation, PM, BA, KP, VR, CSS, SK, LK and CV; writing-review and editing, PM, BA, VR, AAB, SB, MA, RA, SA, and EA; visualization, PM, KP, CSS and SK.; supervision, PM; project administration, PM, LK, SK and CV; funding acquisition, PM, BA, LK and CV. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Use of polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:326-330.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular typing by random amplification of polymorphic DNA and M13 southern hybridization of related paired isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. Clin. Microbiol. J.. 1996;34:87-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA markers to distinguish isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 1992;30:2991-2993.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular studies reveal frequent misidentification of Aspergillus fumigatus by morphotyping. Eukaryot. Cell.. 2006;5:1705-1712.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Keratitis caused by Aspergillus pseudotamarii. Med. Mycol. Case Rep.. 2013;2

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Utility of random amplified polymorphic DNA PCR and TaqMan automated detection in molecular identification of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 1998;36:2057-2062.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of an epidemic of invasive aspergillosis: utility of molecular typing with the use of random amplified polymorphic DNA probes. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J.. 1994;13:386-393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Variation in pathogenicity associated with the genetic diversity of Fusarium graminearum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.. 2002;108:573-583.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of a novel panel of nine short tandem repeats for exact and high-resolution fingerprinting of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2005;43:4112-4120.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic similarity among one Aspergillus flavus strain isolated from a patient who underwent heart surgery and two environmental strains obtained from the operating room. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2000;38:2419-2422.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inter and intraspecific genetic diversity (RAPD) among three most frequent species of macrofungi (Ganoderma lucidum, Leucoagricus sp. and Lentinus sp.) of tropical forest of Central India. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol.. 2018;16:133-141.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Detection and identification of fungal pathogens in blood by using molecular probes. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 1997;35:1353-1360.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymerase chain reaction based detection of fungi in infected corneas. Br. J. Ophthalmol.. 2002;86:755-760.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of random amplified microsatellites to type isolates from an outbreak of nosocomial aspergillosis in a general medical ward. Med. Mycol.. 2005;43:365-371.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aspergillus flavus: human pathogen, allergen and mycotoxin producer. Microbiology. 2007;153:1677-1692.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Environmental investigations and molecular typing of Aspergillus flavus during an outbreak of postoperative infections. J. Hosp. Infect.. 2004;57:149-155.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fusarium keratitis in South India: causative agents, their antifungal susceptibilities and a rapid identification method for the fusarium solani species complex. Mycoses. 2013;56

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid detection and identification of Candida, Aspergillus, and Fusarium species in ocular samples using nested PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2000;38:2902-2908.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of a repetitive DNA probe to type clinical and environmental isolates of Aspergillus flavus from a cluster of cutaneous infections in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2000;38:3612-3618.

- [Google Scholar]

- Filamentous fungal infections of the cornea: A global overview of epidemiology and drug sensitivity. Mycoses. 2015;58:243-260.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Case of keratitis caused by Aspergillus tamarii. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2007;45

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Infectious keratitis caused by Aspergillus tubingensis. Cornea. 2009;28:951-954.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of PCR targeting of internal transcribed spacer regions and single-stranded conformation polymorphism analysis of sequence variation in different regions of rrna genes in fungi for rapid diagnosis of mycotic keratitis. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2005;43:662-668.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Density and molecular epidemiology of Aspergillus in air and relationship to outbreaks of Aspergillus infection. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 1999;37:1752-1757.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of three typing methods for clinical and environmental isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 1995;33:1596-1601.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of polymerase chain reaction to fingerprinting Aspergillus fumigatus by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 1993;31:1117-1121.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan, P., Dóczi, I., Kocsubé, S., Varga, J., Németh, T.M., Antal, Z., Vágvölgyi, C., Bhaskar, M., Kredics, L., 2008a. Aspergillus species in human keratomycosis, Aspergillus in the Genomic Era. 293–330. https://doi.org/10.3920/978-90-8686-635-9.

- Keratitis caused by the recently described new species Aspergillus brasiliensis: two case reports. J. Med. Case Rep.. 2010;4

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Corneal ulcer due to Neocosmospora vasinfecta in an immunocompetent patient. Med. Mycol.. 2008;46

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Restriction enzyme analysis of mitochondrial DNA of the Aspergillus flavus group: A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 1990;56:2441-2452.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of reference strains of the genus Aspergillus. Mycoses. 2001;44:65-72.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Misidentification of Aspergillus nomius and Aspergillus tamarii as Aspergillus flavus: Characterization by internal transcribed spacer, -tubulin, and calmodulin gene sequencing, metabolic fingerprinting, and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-tim. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2014;52:1153-1160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucl. Acids Res.. 1990;18:6531-6535.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]