Translate this page into:

Comparative assessment of total phenolic content and in vitro antioxidant activities of bark and leaf methanolic extracts of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard

⁎Corresponding author. sray@zoo.buruniv.ac.in (Sanjib Ray)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Manilkara hexandra is a traditionally used medicinal plant. The aim of the present study was to analyze in vitro antioxidant potentials of the methanolic leaf (LMEMH) and bark (BMEMH) extracts of M. hexandra in relation to total phenolics. Here, in vitro antioxidant activities of the extracts were tested through 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging, ferric ion reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), hydroxyl radical scavenging (HRS), and the total antioxidant activity (TAC) assays. The EC50 of DPPH free radical scavenging with ascorbic acid, LMEMH, and BMEMH were calculated as 19.06 ± 2.2, 46.62 ± 6.13, and 88.66 ± 24.07 µg/mL respectively. The EC50 of the Fe3+ ion reduction by ascorbic acid, LMEMH, and BMEMH were calculated respectively as 54.06 ± 5.00, 147.45 ± 22.46 and 480.34 ± 91.65 µg/mL. The LMEMH shows more HRS activity and the total phenolic content than the BMEMH. In conclusion, the leaf methanolic extract of M. hexandra has the comparatively more in vitro antioxidant potentials and total phenolics content than its bark methanolic extract.

Keywords

Antioxidant

DPPH

FRAP

Reactive oxygen species

Manilkara hexandra

1 Introduction

Several diseases like acquired immune deficiency syndrome, auto-immune diseases, hyperglycemia, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, atherosclerosis, cataracts, and other old aged diseases are associated with the excess oxidative stress (Majewska et al., 2011). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) like hydroxyl radical (HR), singlet oxygen, peroxides and superoxides that are generated in oxidative metabolic reaction and have the important functions in cellular homeostasis. ROS level can increases radically during the time of environmental stresses. It inflicts damage to the subcellular organelles and ultimately leads to a number of human diseases (Warrier et al., 1995). Therefore, the natural antioxidants have a key role to neutralize the excess ROS (Lee and Shibamoto, 2000; Borneo et al., 2009).

Antioxidants, free radical scavengers, are unstable molecules as they contain unpaired electrons and to become stable they take out electrons from the other molecules (Thambiraj and Paulsamy, 2012). There are various types of free radical scavengers and antioxidants like phenolics, thiols, tri-peptide – glutathione, enzymes – peroxidase, catalase, superoxide dismutase and vitamins – E and C that prevent oxidative stress-induced damage of deoxyribonucleic acids, lipids, and proteins (Sies, 1997, Devasagayam et al., 2003, Vertuani et al., 2004). Many researchers have confirmed that phenolic-rich plant products play an important role in the prevention of cancers, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases (Kris-Etherton et al., 2002; Blazovics et al., 2003; González-Gallego et al., 2014; Ganeshpurkar and Saluja, 2017; García et al., 2018). There is a positive correlation between the habit of polyphenolic compounds containing food consumption and the reduced occurrence of degenerative diseases (Beevi et al., 2010). Phenolic acids, tannins, and flavonoids are the main phenolic compounds. The polyphenols have several phenolic hydroxyl substituents and have been implicated in UV protection and disease resistance (Waterman and Mole, 1994). They are extensively used in foodstuff industry and are considered as an important component of nutraceuticals. The previous study reports indicated a strong positive correlation between the phenolics content and antioxidant activity, as was observed, in oregano, peppermint, clove, sage, garden thyme, and all spices (Dimitrios, 1996).

Manilkara hexandra (Family: Sapotaceae) is widely distributed in South, North and Central India-mainly in Rajasthan, Gujrat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra (Malik et al., 2012). The bark and leaves of M. hexandra are well known for their several medicinal uses. The bark is sweet, aphrodisiac, refrigerant and shows stomachic, astringent, alexipharmic and anthelminthic activities. It is used in the cure of fever, burning sensation, colic, flatulence, hyperdipsia, helminthiasis, hyperglycemia and vitiated conditions of pitta. The stem bark of M. hexandra is rich in procyanidins, saponins, and flavonoids, (Shah et al., 2004; Das et al., 2016). It is also given to the lactating mothers daily once for 3–5 days. The young boiled pods are also eaten. The leaf methanolic extract fraction of M. hexandra is shown to exhibit better antioxidant potential and in vitro α-amylase inhibitory property than the other extract fractions (Patel and Patel, 2015; Dutta and Ray, 2015).

Earlier Nimbekar et al. (2010) showed a concentration-dependent increase in nitric oxide, superoxide, and DPPH free radical scavenging potentials of the bark methanolic extract of M. hexandra. The successive leaf methanolic extract fraction of M. hexandra contains the most potent antioxidants than the other extract fractions (Dutta and Ray, 2015). Thus, in the present state of knowledge, the bark and leaf extracts of M. hexandra are attractive sources of antioxidant compounds. The practice of collection of bark is an issue of concern to plant health and is more harmful than leaf collection. Therefore, in the present study, we intended to establish the suitability of the leaves of M. hexandra over the stem barks for the pharmacological activities. In many studies, the antioxidants were isolated with methanol and our earlier data also indicated that the methanolic extract fraction had the highest in vitro antioxidant activities (Gonzalez-Guevara et al., 2004; Dutta and Ray, 2015). Thus, here also, methanol was used as the solvent for the extraction of phytochemicals from leaf and bark of M. hexandra and a comparative account of in vitro antioxidant property in relation to their total phenolic content was analyzed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

Ammonium molybdate and sulphuric acid were obtained from Qualigens. Sodium phosphate was purchased from Merck. Folin-Ciocalteu and Sodium citrate were purchased from BDH Chemicals Ltd., UK. Benzene and ethyl acetate were obtained from SRL, Pvt. Ltd., India. The tannic acid powder and quercetin were obtained from Himedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India, and Sigma-Aldrich, USA, respectively.

2.2 Extracts preparation

Fresh stem bark and leaves of M. hexandra were collected from The Burdwan University campus. This plant species was taxonomically authenticated by Professor Ambarish Mukherjee, Taxonomist, The University of Burdwan. For future reference, the voucher specimen (No.BUGBSD015) is maintained in the Department of Zoology, The University of Burdwan. The collected plant parts were properly washed with water; shade dried, crushed directly into small pieces using an electric grinder (Philips Mixer Grinder HL1605). The ground leaf and bark powder were stored in airtight containers for future use. The leaf and the bark methanolic extracts of M. hexandra were prepared at room temperature soaking the respective powder in methanol with intermittent agitation for seven days. The extracts were filtered through the Whatman filter paper No. 1 (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA). The extracts were concentrated in a vacuum evaporator at low temperature (50 °C). 10 mL of extract was completely dried in a hot air oven at 60 °C to determine the extract concentration (Dutta and Ray, 2015).

2.3 In vitro antioxidant assays

2.3.1 DPPH radical scavenging assay

To determine in vitro antioxidant activity of the bark and the leaf methanolic extracts of M. hexandra, the DPPH free radical scavenging assay was performed (Brand-Willims et al., 1995; Ayoola et al., 2008). DPPH methanolic stock solution (0.002%) and the standard ascorbic acid (AA) solution (5–100 µg/mL) were freshly prepared. 1 mL of AA and the extracts of M. hexandra (5–100 µg/mL) were taken in the respective test tubes. Then in each test tube, 0.5 mL DPPH (1 mM), and 3 mL methanol were added. The reaction mixtures were kept at room temperature (25 0C) in dark for 35 min and then the OD was measured using a spectrophotometer (UV-1800 series, Shimadzu, Japan) at 517 nm. The percentage (%) of DPPH free radical scavenging activity was calculated using the following equation—

EC50 of the extracts and ascorbic acid for DPPH free radical scavenging were calculated.

2.3.2 Ferric ion reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

FRAP assay as described by Oyaizu (1986) was followed here to determine the reducing power of the leaf and bark methanolic extracts of M. hexandra. 0.5 mL AA and the extracts (0–100 μg/mL) were added to the respective test tubes and then (0.2 M) 1 mL phosphate buffer saline, and 1 mL K3Fe(CN)6 (1%) were added to the mixtures and incubated for 20 min at 50 °C. Then 1 mL Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (10%) was mixed to each of the test tubes and then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm. The supernatant (1.5 mL) was diluted with an equal volume of distilled water and then 0.1% FeCl3 (0.1 mL) solution was added to it and then the OD was taken at 700 nm with a spectrophotometer (UV-1800 Series, Shimadzu, Japan). The EC50 of both the extracts and ascorbic acid were calculated.

2.3.3 Hydroxyl radical scavenging (HRS) activity

Hydroxyl radicals are highly reactive free radicals. The HRS activity was determined following the procedure as described by Smirnoff and Cumbes (1989). The reaction mixture [containing 0.7 mL of H2O2 (6 mM), 1 mL of FeSO4 (1.5 mM), 0.3 mL sodium salicylate solution (20 mM), and sample 1 mL (various concentrations, 100–500 µg/mL, in the respective test tubes)] was incubated at 37 °C in a water bath for 60 min and then using a spectrophotometer (UV-1800 Series, Shimadzu, Japan) the OD (absorbance) was measured at 510 nm. The HRS power was estimated using the following equation- where, A0, the OD of control; A1, the OD of extract; and A2, the OD without sodium salicylates.

2.3.4 Total antioxidant assay

The total antioxidant (ascorbic acid equivalent) potentials of the leaf and bark methanolic extracts of M. hexandra were determined through phosphomolybdate assay. The extracts were tested to see their ability to reduce Mo (VI) to Mo (V), green Mo complex, which has the highest absorbance at 695 nm (Yen and Chen, 1995). In each of the test tubes, 0.3 mL test sample (100 µg/mL) was taken and then 3 mL reagent mixture (0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate) was added. Then the test tubes were kept in a water bath for 90 min at 95 °C and using a spectrophotometer (UV-1800 Series, Shimadzu, Japan) OD was recorded and compared with ascorbic acid (Garrat, 1964).

2.4 Phytochemical detection

Steroids, alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, phlobatannins, triterpenoids, anthraquinones, carbohydrates, saponins, and glycosides test were performed following the standard protocols (Harborne, 1973; Trease and Evans, 1989) as described earlier in detail (Dutta and Ray, 2015).

2.5 Determination of phenolics

2.5.1 Total phenolics

Phenolics, aromatic substances with one or more hydroxyl groups, are secondary plant metabolites with heterogeneous groups having radical scavenging and antioxidant activity. The total phenolic content of the extracts was estimated with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (Makkar et al., 1993). From the stock tannic acid solution (0.5 mg/mL) the different standard concentrations (2.5–25 µg/mL) were prepared. 10 μL of the sample, 990 μL distilled water, 0.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu (1 N) and 2.5 mL 20% sodium carbonate solution (25 g of Na2CO3, 10 H2O in 125 mL distilled water) were mixed in the respective test tubes and the test tubes were kept for 40 min in dark. The optical density was recorded at 725 nm using a spectrophotometer and based on the tannic acid standard curve the total phenolic content was estimated.

2.5.2 Total flavonoids

The AlCl3 colorimetric method was used for estimation of total flavonoids (Chang et al., 2002). 1 mL extract (1 mg/mL), 2 mL distilled water, 3 mL Sodium nitrite (5%, 5 g in 100 mL distilled water) and 0.3 mL Aluminium chloride (10% aqueous) were mixed in the respective test tubes. After 6 min, 2 mL Sodium hydroxide (1 M) was added and the volume increased up to 10 mL by adding more distilled water. The OD of the reaction mixtures were recorded with a spectrophotometer (UV-1800 Series, Shimadzu, Japan) at 510 nm. The flavonoids content (quercetin equivalent) of the extracts was calculated.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All the assays were performed at least in triplicate and the data points were expressed as Mean ± SEM. The statistical significance of differences between the groups was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a confidence level of 95% (pα=0.05).

3 Result and discussion

3.1 DPPH assay

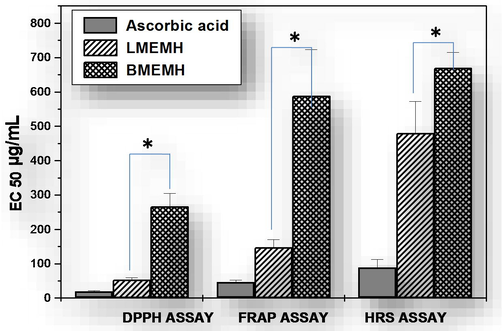

Data indicate that the leaf methanolic extract (LMEMH) and the bark methanolic extract (BMEMH) of M. hexandra have the differential capacities to scavenge the DPPH free radicals. The LMEMH showed the better DPPH free radical neutralizing activity as well as a lower effective concentration for 50% free radical scavenging (EC50) value than the BMEMH. The EC50 of DPPH free radicals scavenging of ascorbic acid, LMEMH and BMEMH were calculated as 19.06 ± 2.2, 46.62 ± 6.13, and 88.66 ± 24.07 µg/mL respectively (Fig. 1). A DPPH free radical becomes neutralized stable diamagnetic molecule when it accepts an electron or hydrogen radical (Sochor et al., 2010). The oxidative stress and the cellular damage are related to many chronic diseases. The bark methanolic extract of M. hexandra has antioxidant potential (Nimbekar et al., 2010). The most of the antioxidant compounds were extracted with the polar solvents (Gonzalez-Guevara et al., 2004). Earlier we have reported that the successive leaf methanolic extract fraction of M. hexandra was the most potent antioxidant fraction (Dutta and Ray, 2015) and here we report the leaf methanolic extract contains more DPPH free radical scavengers than the stem bark methanolic extract.

EC50 (µg/mL) of LMEMH and BMEMH for 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging, ferric ion reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), and hydroxyl radical scavenging (HRS) potentials. The level of confidence was considered at 95% (pα=0.05) (ANOVA) for the determination of differences between the two groups.

3.2 FRAP assay

For FRAP assay, the leaf and the bark methanolic extracts of M. hexandra and ascorbic acid were used. Data indicate that both the extracts and ascorbic acid could reduce the Fe3+ ion in a concentration-dependent manner. Here, the LMEMH has shown more ferric ion reducing antioxidant power than the BMEMH. The effective concentration for 50% reduction (EC50) of the Fe3+ ion with ascorbic acid, LMEMH, and BMEMH was calculated as 54.06 ± 5.00, 147.45 ± 22.46 and 480.34 ± 91.65 µg/mL respectively (Fig. 1). The higher ferric ion reducing the power of LMEMH is also in accordance with its higher quantity of phenolic content (Fig. 2). Like DPPH, FRAP assay data also indicate that the leaves are the comparatively better depository of antioxidants than bark of M. hexandra.

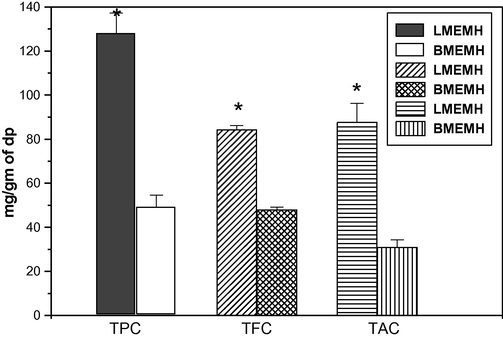

The total phenolics, flavonoids, and total antioxidant of the LMEMH and BMEMH. TPC, total phenolic content; TFC, Total flavonoids content; TAC, Total antioxidant content; dp, dried powder. The level of confidence was considered at 95% (pα=0.05) (ANOVA) for the determination of differences between the two groups.

3.3 Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

The hydroxyl radicals can affect the various biomolecules like proteins, polypeptides, nucleic acids and lipids (Balaban et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2004). Here, data indicate LMEMH, BMEMH, and ascorbic acid could scavenge hydroxyl radicals effectively. The LMEMH showed more hydroxyl radical scavenging activity than the BMEMH. The half maximum effective concentrations (EC50) were 589.34 ± 133.95, 670.48 ± 44.79 and 267.28 ± 36.88 µg/mL respectively for LMEMH, BMEMH and ascorbic acid. The assays were done in triplicate and data are expressed as Mean ± SEM. The level of confidence was considered at 95% (pα=0.05) (ANOVA) for the determination of differences between LMEMH and BMEMH (Fig. 1). The leaf methanolic extract of M. hexandra showed more hydroxyl radical scavenging potential than the bark methanolic extract and that may be due to the presence of its more polyphenolics, reducing agents, and hydrogen donors (Hatano et al., 1989).

3.4 Total antioxidant activity

Antioxidants scavenge the free radicals and detoxify the harmful actions of it. The plant products rich in antioxidants play an important role in the prevention of ROS induced diseases (Hossain and Nagooru, 2011; Gerber et al., 2002). The phosphomolybdate assay measures the ability of a sample to destroy a free radical by transferring an electron to the latter. Data indicate that leaf methanolic extract of M. hexandra contains more antioxidants than that of the bark methanolic extract. The LMEMH (87.74 ± 8.52 mg per 1 g of dlp equivalent ascorbic acid content) contains more total antioxidant activity than the BMEMH (31.01 ± 3.29 mg per 1 g of dbp equivalent ascorbic acid content) (Fig. 2). The various vegetables (ginseng leaf, pepper leaf, sweet potato, cowpea, colored cabbages, broccoli etc.) and fruits (plums, dates, berries, grapes etc.) are rich in antioxidants (Manganaris et al., 2014; Deng et al., 2012; Fu et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2010). Antioxidant, antimutagenic, and antitumor activities of polyphenolics are well accepted (Li et al., 2009; Othman et al., 2007) and this differential total antioxidant activity of the LMEMH and BMEMH may be based on their total phenolic content.

3.5 Phytochemical analysis

Throughout the World, experiments are being conducted to find out the safe and bioactive natural antioxidants of plant origin. The preliminary chemical analyses indicate the presence of phenolics (flavonoids, tannins), terpenoids, and alkaloids in both the extracts. Steroids and anthraquinones are absent in all the extracts (Table 1). There are similar reports on the antioxidant activity of the crude extracts of Ampelocissus latifolia, Calophyllum inophyllum and M. hexandra where the phytochemical analysis indicated the presence of phytochemicals like phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids etc. (Pednekar and Raman, 2013; Dutta and Ray, 2015). +; Present, −; Absent.

Sl No

Phytochemicals

Tests performed

Result

LMEMH

BMEMH

1

Tannins

FeCl3

+

+

Alkaline reagent

+

+

2

Terpenoids

Kantamreddi et al. (2010)

+

+

3

Alkaloids

Mayer’s

+

+

Wagner’s

+

+

Hager’s

−

+

4

Phlobatannins

HCl

−

+

5

Flavonoids

Zinc hydrochloride

+

+

Alkaline solution

−

−

6

Carbohydrates

Benedict’s

+

+

7

Saponins

Froth

−

−

8

Reducing sugars

Fehling’s

−

−

9

Steroids

Kantamreddi et al. (2010)

−

−

10

Anthraquinones

Borntrager’s

−

−

11

Glycosides

Alkaline reagent

−

−

Fehling’s

−

−

3.6 Total phenolics and flavonoids content

The LMEMH contains more tannic acid equivalent phenolic content (128.10 ± 9.15 mg/g of dried leaf powder, dlp) than the BMEMH (49.32 ± 5.21 mg/g of dried bark powder, dbp)(Fig. 2). The phenolics, the major group of secondary metabolites, are associated with the various pharmacological activities like antimicrobial, antiviral, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-carcinogenic (Bravo, 1998; Mohammedi and Atik, 2011). In human diets, the plant polyphenolics are the most abundant antioxidants. There exists a positive correlation between the total phenolic contents and the antioxidant activities of the plant extracts (Dutta and Ray, 2015; Sun et al., 2002). The LMEMH has more quercetin equivalent flavonoid content (84.45 ± 1.78 mg per 1 g of dlp) than in BMEMH (48.00 ± 1.09 mg per 1 g of dbp)(Fig. 2). Flavonoids, a group of phenolics, derived from tyrosine, phenylalanine, and malonate, are well known for their antioxidant activities (Hertog et al., 1993). Moreover, over-accumulation of flavonoids could enhance oxidative and drought tolerance phenomenon in Arabidopsis (Nakabayashi et al., 2014).

4 Conclusion

The in vitro antioxidant potentials of the leaf (LMEMH) and bark extracts (BMEMH) of M. hexandra were analyzed in relation to their total phenolic and flavonoids contents. Here, the LMEMH showed a comparatively better DPPH free radical scavenging; ferric ion reducing antioxidant power, HRS activities, and also the relatively higher total antioxidant activities in terms of ascorbic acid equivalent contents. Further, it was correlated with the presence of the higher quantity of total phenolic and flavonoids contents in LMEMH than BMEMH. Therefore, it may say that Manilkara hexandra leaves are more suitable than the bark as a source of antioxidants. In conclusion, the M. hexandra leaves may be preferred as a natural source of antioxidants instead of stem bark, though, further investigation is necessary to explore in vivo antioxidant efficacy and toxicity.

Acknowledgements

Authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the DST-INSPIRE fellowship (IF 110690) under INSPIRE Program, and the infrastructural support of the UGC-DRS, DST-FIST, and DST-PURSE, Govt. of India. Professor Ambarish Mukherjee has kindly authenticated the plant species.

References

- Phytochemical screening and free radical scavenging activity of some Nigerian medicinal plants. J. Pharm. Sci. Pharm. Pract.. 2008;8:133-136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polyphenolics profile, antioxidant and radical scavenging activity of leaves and stem of Raphanus sativus L. Plant. Foods. Hum. Nutr.. 2010;65:8-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural antioxidants and tissue regenerations: curative effect and reaction mechanism. In: Majumdar D.K., Govil J.N., Singh V.K., eds. Recent Progress in Medicinal Plants. Studium Press; 2003. pp. 107

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant capacity of medicinal plants from the Province of Cordoba (Argentina) and their in vitro testing in a model food system. Food Chem.. 2009;112(3):664-670.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol.. 1995;28(1):25-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polyphenols: chemistry, dietary sources, metabolism, and nutritional significance. Nutr. Rev.. 1998;56:317-333.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-hyperglycemic activity of hydro-alcoholic bark extract of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2016;8(4):1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of antioxidant property and their lipophilic and hydrophilic phenolic contents in cereal grains. J. Funct. Foods. 2012;4(4):906-914.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methods for estimating lipid peroxidation: analysis of merits and demerits (minireview) Indian J. Biochem. Biophys.. 2003;40(5):300-308.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of in vitro free radical scavenging activity of leaf extract fractions of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb) Dubard in relation to total phenolic contents. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2015;7(10):296-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant capacities and total phenolic contents of 62 fruits. Food Chem.. 2011;129(2):345-350.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flavonoids effects on hepatocellular carcinoma in murine models: a systematic review. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med.. 2018;2018:1-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Quantitative Analysis of Drugs. Japan: Chapman Hall; 1964. p. :456-458.

- Bull. Cancer. 2002;89:293.

- Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of dietary flavonoids. Polyphen. Human Health Dis. 2014:435-452.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening and in vitro antiherpetic activity of four Erythtroxylum species. Acta. Farmaceut. Bonaer.. 2004;23(4):506-509.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical Methods. London: Chapman and Hall Ltd; 1973. p. :49-188.

- Effects of tannins and related polyphenols on superoxide anion radical and on 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical. Chem. Pharm. Bull.. 1989;37:2016-2021.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dietary antioxidant flavonoids and risk of coronary heart disease, the Zutphen Elderly study. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1007-1011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical profiling and total flavonoids contents of leaves crude extract of endemic medicinal plant Corydyline terminalis (L.) Kunth. Pharmacognosy. J.. 2011;3(24):25-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary phytochemical analysis of some important Indian plant species. Int. J. Pharma. Bio. Sci.. 2010;1:351-357.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactive compounds in foods: their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am. J. Med.. 2002;113:71-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant properties of aroma compounds isolated from soybeans and mung beans. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2000;48(9):4290-4293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activities of extracts and fractions from Lysimachia foenum-graecum Hance. Bioresour. Technol.. 2009;100(2):970-974.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antioxidant potential of flavonoids: an in vitro study. Acta. Pol. Pharm.. 2011;68(4):611-615.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gravimetric determination of tannins and their correlations with chemical and protein precipitation methods. J. Sci. Food. Agric.. 1993;61:161-165.

- [Google Scholar]

- Socio-economic and horticultural potential of Khirni [Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard]: a promising underutilized fruit species of India. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol.. 2012;59:1255-1265.

- [Google Scholar]

- Berry antioxidants: small fruits providing large benefits. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2014;94(5):825-833.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of solvent extraction type on total polyphenols content and biological activity from Tamarix aphylla (L.) Karst. Int. J. Pharm. Biol.. 2011;Sci.2:609-615.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J.. 2014;1, 77(3):367-379.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro antioxidant activity of methanolic extract of Manilkara hexandra. J. Adv. Pharmacol. Toxicol.. 2010;11(2):19-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of cocoa beans. Food Chem.. 2007;100(4):1523-1530.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on products of browning reactions: antioxidative activities of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn. J. Nutr.. 1986;44:307-315.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic activity of leaves of Manilkara Hexandra: Role of carbohydrate metabolising α-amylase enzyme. ARPB.5 2015:863-867.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant potential with FTIR analysis of Ampelocissus latifolia (Roxb.) Planch. leaves. Asian J. Pharm Clin. Res.. 2013;6(1):157-162.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard against experimentally-induced gastric ulcers. Phytother. Res.. 2004;18(10):814-818.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119(7):941-953.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of compatible solutes. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:1057-1060.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fully automated spectrometric protocols for determination of antioxidant activity: advantages and disadvantages. Molecules. 2010;15:8618-8640.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of common fruits. J. Agric. Food. Chem.. 2002;50(25):7449-7454.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro antioxidant potential of methanol extract of the medicinal plant, Acacia caesia (L.) Willd. Asian. Pac. J Trop. Biomed.. 2012;2(2):732-736.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacognosy Brailliar Tiridel Can (13th ed.). Macmillian Publishers; 1989.

- The antioxidants and pro-antioxidants network, an overview. Curr. Pharm. Des.. 2004;10(14):1677-1694.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Medicinal Plants a Compendium of 500 Species. Orient Blackswan,-Material Medica; 1995.

- Analysis of phenolic plant metabolites. In: Lawton J.H., Likens G.E., eds. Methods in Ecology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994. p. :36-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological activities of polyphenols from grapes. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2010;11(2):622-646.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of various tea extracts in relation to their antimutagenicity. J. Agric. Food. Chem.. 1995;43:27-32.

- [Google Scholar]