Colonization dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) in Ilex paraguariensis crops: Seasonality and influence of management practices

⁎Corresponding author. mariasilvanavelazquez@gmail.com (Velázquez María Silvana),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis St. Hill.) is a native species from subtropical regions of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are symbiotically associated with 82% of the vegetable species including crops of economic importance. The aim of the present study was to determine the association of yerba mate with AMF growing in natural and crop conditions, and to evaluate the influence of tillage practices and seasonality on root colonization. We selected five situations ranging from old systems to recent implementations with different agricultural managements and intensity of tillage, as reference native trees were analyzed. Root samples of yerba mate were extracted in winter and summer during the years 2013–2014. The percentage of root colonization was determined. Significantly higher values of colonization were found in native trees. Regarding seasonality, significantly higher values on the total mycorrhizal colonization were observed in winter. Organic matter and nitrogen were the soil factors that showed significant correlation with the percentage of colonization. This work confirms the association of I. paraguariensis with AMF, showing that yerba mate is a host species under both crop and natural conditions. Even though crop management of yerba mate is compatible with the symbiosis, it affects the colonization negatively.

Keywords

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Ilex paraguarensis

Colonization

Seasonality

Managements practices

1 Introduction

The yerba mate, Ilex paraguarienses St.-Hill. (family Aquifoliaceae) is a species originally from South America, native to subtropical regions of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. It is native to the phytogeographic region of Selva Paranaense of the Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest. Argentina is the main manufacturer and consumer of yerba mate worldwide, with 200,000 implemented hectares and 17,400 producers distributed in Misiones and NE of Corrientes, being the utmost important socio-economic crop at the regional level (INYM, 2011).

Mycorrhizal associations exert great influence on diverse agroecological and ecosystemic processes. Currently, there is a growing awareness of soil biodiversity and of the potential of these natural resources as alternative or complementary technologies to agrochemicals. Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) (phylum Mucoromycota; Spatafora et al. 2016) is an interesting strategy for improving crop yields because arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis provides numerous services to crops (Gianinazzi et al., 2010), including efficient use of fertilizers and soil nutrients (Javaid, 2009), protection against drought stress (Porcel et al., 2007; Porcel and Ruiz-Lozano, 2004) and diseases (Liu et al., 2007), increased N-fixation in legumes (Barea and Azcon-Aguilar, 1983; Haselwandter and Bowen, 1996), and improved soil physical properties (Hallett et al., 2009). However, since AMF are obligate biotrophs that require a host plant to complete their life cycle (Smith and Read, 2008). They colonize the root tissues through sources of propagules existing in the soil, including mature spores, mycorrhized root fragments or mycorrhized plants that grow in their vicinity. AMF hyphae generally do not have septa and may grow either extra or intraradically. Intraradical mycelium produces characteristically branched structures inside the cortical cells called arbuscules. Many AMF species also form large globular intraradical cells called vesicles that have a reserve function. Although arbuscules are considered diagnostic structures of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis, there is a wide range of other intraradical structures formed by AMF, including intracellular hyphal coils, which sometimes occur without the presence of arbuscules. The spores of AMF are asexual, multinucleated and produced directly by the mycelium, both inside and outside the root (Smith and Read, 2008).

Many studies worldwide have focused on the use of AMF in sustainable agriculture as a mechanism to maintain efficient commercial crops (Andrews et al., 2012; Pellegrino et al., 2011). There are also countless studies on this subject for tropical and subtropical crops (e.g. coffee, cacao, avocado, banana, pineapple, citrus) and forest trees, which showed the positive effects of mycorrhization on their biometric characteristics (Adriano-Anaya et al., 2011; Aguirre-Medina et al., 2011; Colozzi-Filho-Siqueira, 1986; da Silveira et al., 2003; de Oliveira and de Olivera, 2005). To add there are few rigorous studies that hither to established the degree of yerba mate association with AMF, especially under field conditions. Andrade et al. (2000) reported the presence of arbuscules, coils, appressoria, intracellular aseptate hyphae, and vesicles in roots of I. paraguarensis in Santa Catarina, Brazil

In Argentina, more than 60% of the area cultivated with yerba mate has serious problems of soil degradation. Its recovery demands of already developed technologies, and of research and technological innovations of existing tools where AMF would play an important role. In a survey of yerba mate seedlings from 10 municipalities in the States of Paraná and Santa Catarina, Gaiad and Lopes (1980) registered that roots from 90% of the samples showed some degree of mycorrhizal association. The aim of the present study was to determine the influence of management practices and seasonality on root colonization on plants of yerba mate.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

Productive sites were located in Municipality of Gobernador Virasoro, Department of Santo Tomé, Corrientes (Site 1–5). While samples from native plants (Site 6) were taken from the locality of San Pedro, Misiones (Table 1). Experimental plots were situated on the Díaz de Vivar soils series, which is taxonomically classified in the Kandihumults subgroup of the Ultisols order. In general, they are known as red hills or red clay soils, whose effective depth exceeds 150 cm, and have well-drained slopes that ranged from 2 to 5% (Escobar et al., 1996).

| Sampling sites | Age of crops | Georeference | Altitude (masl) | Plant density (pl/ha) | Characteristics | Yields (kg/ha/y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 28°00′32′'S | Extreme soil deterioration | ||||

| Y28 | 1928 | 55°50′34′'W | 144 | 450 | No fertilization | <2000 |

| High harvesting | ||||||

| Low soil degradation | ||||||

| Site 2 | 1958 | 28°03′32′'S | 140 | 1000 | Optional fertilization | 4500–5500 |

| CU | 55°49′45′'W | Chemical weed control | ||||

| Moderate harvesting | ||||||

| Site 3 | 28°06′42′'S | Sustainable management | ||||

| Y24 | 1924 | 56°02′52′'W | 141 | 600 | No fertilization | 4000 |

| Moderate harvesting | ||||||

| Site 4 | 1984 | 28°08′52′'S | 146 | 2600 | Fertilization of 300 kg/ha/y | 10,700 |

| CN | 55°57′47′'W | N-P-K (15:0:40) | ||||

| Site 5 | 1992 | 28°11′04′'S | 135 | Fertilization of 400 kg/ha/y | ||

| L49 | 56°00′43′'W | 4000 | N-P-K (18:0:36) | 12,000 | ||

| Chemical weed control | ||||||

| Site 6 NAT |

26°39′36′'S | 569 | Trees that grow spontaneously in the undergrowth of the rainforest | |||

| 54°08′21′'W | of the Misiones and that were not yet commercially exploited | |||||

The climate is humid subtropical, according to the Köppen classification, and the mean annual temperature is 21.5 °C with the highest mean temperature in January (37.2 °C) and the lowest in July (0.9 °C). Rainfall is mainly concentrated in fall and spring, and the mean annual rainfall is 1923 mm (Meteorological Center, “Instituto Agrotécnico Víctor Navajas Centeno”, Gobernador Virasoro, Corrientes).

2.2 Sampling sites

We considered as variables five contrasting situations with respect to the historical crop management and tillage intensity of yerba mate, ranging from old systems with a minimum production (i.e. traditional crops without fertilization, intense tillage and excessive branch and leaf harvesting) to more recent implantations with the maximum yields (i.e. fertilized crops with high plant density and high technology). As reference data, native trees of yerba mate that grow spontaneously in the undergrowth of the rainforest of Misiones were analyzed (Table 1). Temperature conditions remained almost constant for each season at the sampling sites during the 2-year period, although differences in rainfall between sampling years were registered (Table 2). Climate data were provided by Meteorological Stations “Red del Ministerio de la Producción” (Corrientes) and “Estación Experimental del INTA Cerro Azul” (Misiones) for the sampling sites located in Corrientes and Misiones, respectively.

| Sampling sites | Location | Temperature (°C) | Rainfall (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | ||||||

| Minimum | Maximum | Minimum | Maximum | Winter | Summer | Winter | Summer | ||

| Y28 | |||||||||

| CU | |||||||||

| Y24 | Corrientes | 11.5° | 35.1° | 10.4° | 33.8° | 264.7 | 586.9 | 714.6 | 1083.3 |

| CN | |||||||||

| L49 | |||||||||

| NAT | Misiones | 9.7° | 31.5° | 11.4° | 31.8° | 480.5 | 630 | 689 | 1157 |

2.3 Sampling

In order to obtain samples of soil and roots, at sampling sites 1 to 5 (implemented crops of yerba mate) three pseudo replicates were selected, each consisting in a linear transect (line) separated by 10 lines. At each transect, three plants separated by a distance of 10 plants were sampled. Each sample was analysed separately. In the case of sampling site 6 (NAT: native trees), three trees of yerba mate separated at least by 100 meters were selected.

Sampling was performed in winter and summer (stages of lower and higher physiological activity of yerba mate) during the years 2013 and 2014. Samples were taken from up to 15 cm depth from one part of the root system and the rhizosphere soil and stored in polyethylene bags (Ziploc®) at 4 °C until processing.

2.4 Soil analysis

Six single soil samples from each sampling site were pooled together to obtain a composite sample used for chemical analysis. Soil pH was measured in a 1:2.5 (w/v) soil to water ratio, organic carbon (C) was determined by the wet-oxidation method of Walkley and Black (1934), total N by the micro-Kjedahl method (Jackson, 2005), and P concentration according to Bray-Kurtz I; exchangeable cations were extracted with 1.0 N ammonium acetate at pH 7.0; and exchangeable acidity with 1.0 N calcium acetate at pH 7.0. All analyses were carried out in the Soil Laboratory of “Estación Experimental Agropecuaria”, “Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria”, Misiones, Argentina.

2.5 Percentage of mycorrhizal colonization

To highlight AMF structures, samples of roots were stained following the methods described in Phillips and Hayman (1970) and the percentage of mycorrhizal colonization was estimated according to McGonigle et al. (1990). These analyses were conducted at “Instituto Spegazzini”, “Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo” (UNLP), La Plata, Argentina.

2.6 Statistical analyses

Data of concentrations of soil chemical (organic matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, exchangeable acidity, base saturation, exchangeable aluminium) and total colonization per sites were subjected to one-way analysis of variance. A mixed model ANOVA (Pinhero and Bates, 2000) was performed to test for differences in the total colonization, internal and external mycelia, entry points, vesicles and arbuscules in sites, seasons, and years. Differences between means were compared using Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

The relationship between the percentages of total colonization and soil chemical factors was analyzed using a simple linear correlation analysis (Pearson). Correlation between variables was considered significant when the probability associated with the correlation coefficient was p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with InfoStat Professional version 2013. No data transformation was required because colonization percentage and soil chemical factors were normally distributed.

3 Results

3.1 Soil characteristics

Soil chemical factors at the sampling sites are shown in Table 3. All values of OM in the crop areas were similar among them and were lower than NAT, except Y24, that was not significantly different of NAT. The N concentration was similar at all sites, except at NAT where it was significantly higher. The lowest concentrations of Ca and Mg were observed in CN and L49. For K, only CU, Y28 and L49 (lower levels) differed from CN (higher level) - the others were similar. CN, CU, Y28 and Y24 presented similar values of pH.

| Sampling sites | OM (%) | N (%) | P (ppm) | K (cmol/kg) | Ca (cmol/kg) | Mg (cmol/kg) | CEC (cmol/kg) | Ac. (cmol/kg) | V (%) | pH | Al Exch. (cmol/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y28 | 3.74a | 0.22a | 4.18a | 0.20a | 4.89bc | 2.97b | 8.13bc | 10.9a | 40.97b | 5.25ab | 0.36a |

| CU | 3.63a | 0.21a | 4.45a | 0.29a | 4.27b | 2.08b | 6.69a | 14.36bc | 31.93ab | 4.89ab | 0.59ab |

| Y24 | 3.90ab | 0.22a | 4.86a | 0.49ab | 5.00bc | 2.88b | 8.43bc | 12.62ab | 38.17b | 5.10ab | 0.32a |

| CN | 3.74a | 0.22a | 3.79a | 0.81b | 2.09a | 0.85a | 3.93a | 14.82bc | 21.93a | 4.83ab | 0.77b |

| L49 | 3.40a | 0.22a | 4.09a | 0.64a | 2.56a | 0.87a | 4.15a | 15.53c | 18.62a | 4.68a | 0.86b |

| NAT | 4.41b | 0.26b | 3.99a | 0.54ab | 6.27c | 7.22b | 9.29c | 12.86ab | 37.92b | 5.67c | 0.24a |

3.2 Arbuscular micorrhizal fungi colonization

Mycorrhizal structures associated with root colonization in yerba mate were internal hyphae, vesicles and arbuscules.

We evaluated the total percentage of colonization and internal structures of AMF in yerba mate plants according to the sites, seasonality, years and the interaction between them.

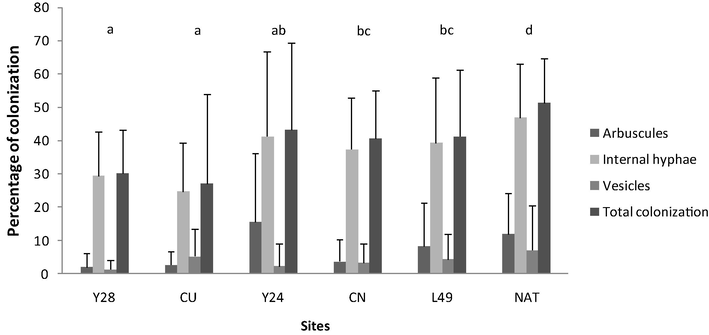

The percentages of total mycorrhizal colonization and mycorrhizal structures associated with root colonized (arbuscules, internal hyphae and vesicles) in different sites are shown in Fig. 1. Significant differences among the six sites were observed, with the highest values registred in NAT and the lowest values in Y28 and CU.

- Percentage of root colonized (arbuscules, hyphae internal, vesicles, and total colonization) in yerba mate crop at the six sites analyzed. Values are means for the sampling sites during 2013 and 2014. The same letter above the bars indicates that values do not differ significantly by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). References: L49 (Loma 49), CN (Carmelo Nuevo), CU (Colonia Unión), Y24 (Yerbal 24), Yerbal 28 (Y28), and NAT (native plants).

When analyzing the effect of seasonality, significant differences in the total colonization between summer and winter were found (p < 0.05). Higher percentages of colonization were registered in winter than in summer (67.5% y 42% respectively). Total colonization also shown significant differences between years. A 49,5% of colonization was registered in the year 2013, and 60% in 2014. Significant interactions for season-sites were found (p < 0.05) in the percentages of total mycorrhizal colonization (Table 4).

| Internal hyphae | Vesicles | Arbuscules | Total colonization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | df | F | P | |

| Sites | 5 | 3.72 | <0.05* | 5 | 1.17 | 0.33 | 5 | 2.42 | <0.05* | 5 | 1.68 | <0.05* |

| Season | 1 | 11.94 | <0.05* | 1 | 2.77 | 0.1 | 1 | 10.01 | <0.05* | 1 | 10.0 | <0.05* |

| Sites x Season | 5 | 5 | <0.05* | 5 | 2.85 | <0.05* | 5 | 1.61 | 0.17 | 5 | 2.43 | <0.05* |

When considering only the percentages of internal hyphae and arbuscules, significant differences between sampling sites were observed, being the highest values found at NAT and Y24 and the lowest at CU and Y28. Almost all mycorrhizal structures except the percentage of vesicles showed significant differences between seasons and between sites. Significant interactions for season-sites were found in internal hyphae and vesicles.

The percentage of total mycorrhizal colonization was significantly correlated (p < 0.05) with the soil content of organic matter (r = 0.92) and N (r = 0.88)

4 Discussion

This study confirms the association of I. paraguariensis with AMF under different crop situations and in native plants growing under natural conditions. Bergottini et al. (2017) have analyzed the diversity of the root-associated microbiome of this crop. Also, there are many studies in subtropical and tropical species of fruit and forest trees, such as coffee (Aguirre-Medina et al., 2011; Montilla et al., 2005), cacao (Aguirre-Medina et al., 2007) and avocado (da Silveira et al., 2003; Montañez Orozco et al., 2010), which showed similar values of colonization to those obtained in the present work. Root colonization by AMF under field conditions is determined by several aspects, such as soil physical and chemical factors (pH, temperature, aeration, texture and P and organic matter contents), climate (intensity and duration of light) and crop management (soil preparation, application of agrochemicals and cultural practices) (Pérez and Vertel, 2010).

Our results showed higher mycorrhizal colonization in NAT than in cultivated sites. The lowest colonization values were registered in Y28 and CU, which are the sites with higher intensity of tillage. The history of culture of a particular site is very relevant to encourage the early establishment of a mycorrhizal colonization and capitalize before its benefits. Soils without tillage or with reduced intensity are appropriate to ensure the persistence of a diverse population of AMF in the soil and maintain the integrity of the extraradical mycelium (Goss et al., 2017). Colonization from an intact extraradical mycelium occurs earlier and develops more rapidly than from spores, colonized root segments or fragmented hyphae. Therefore, it is considered that AMF colonization is more effective starting from an intact extraradical mycelium. Karasawa et al. (2001) indicated that the potential inoculum in soil and colonization capability remains more constant in natural ecosystems than in agricultural systems. Agricultural practices are a source of disturbance that affect both dynamics and diversity of AMF, lowering the propagules density and colonization capability of soils.

Considering the sites under cultivation, the higher percentage of colonization was found at Y24. In this site, a sustainable management is used which allows to maintain the soil microbiota undisturbed. Hawkins and George (2001) reported that in systems with no inputs, the propagule bank in the soil remains diverse and active. In this way, mycorrhizal association is favored, as is shown in this study.

Our study shows that the percentage of AMF colonization correlated significantly with organic matter and N contents. The highest organic matter and N contents, characteristic of rainforest environments, were found in the soil samples from NAT and correlated significantly with the percentage of AMF colonization. Jodice and Nappi (1987) reported that the content of soil organic matter positively influenced AMF activity. Regarding N, Chen et al. (2014) considered that AMF colonization is not influenced by the concentration of this nutrient in soil. However, it has also been frequently observed that the effect of N concentrations on AMF colonization depends to a large extent on particular conditions of each crop and consequently, no clear pattern can be predicted (Chen et al., 2014; Treseder 2004).

In addition to the influence of soil type and management practices, it is important to consider the influence of seasonality. In this study, a higher percentage of colonization was found in winter (lower physiological activity). Bohrer et al. (2004) indicated that seasonality has minimum influence on arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization, and that it should be explained through host plant phenology. According to this, Mullen and Schmid (1993) confirmed that, in some species, higher values of colonization occurs when the plant needs to accumulate P, before the season of maximum physiological activity.

Differences found in colonization between years 2013–2014 can be explained by the rainfalls, since temperature variation between 2013–2014 was not registered in the sampling sites. To analyze the relationship between AMF colonization and rainfall, not only the annual rainfall but also its distribution should be considered, particularly of rainfall that occurred in the four months prior to sampling. Due to the type of soil and to the way in which the yerba mate is grown, it is considered that under field conditions, the vegetative state of the crop at a given time better reflects the water status during the last three to four months than the total annual rainfall. For this reason, we considered the rainfall that occurred in May, June, July and August for the winter sampling, while for the summer sampling, the rainfall that occurred in September, October, November and December. In this study, AMF colonization was positively correlated with rainfall. At NAT (Misiones), rainfall during 2014 was 89% higher than in 2013. These differences were correlated (r = 0.94, data not shown) with an increase in colonization of 19% during the rainiest year. The same pattern was observed for the cultivated sites Y28, Y24, CU, CN and L49 (Corrientes), where it was registered 45% more rainfall in 2014 than in 2013 and an increase in colonization of 12%. These findings are in agreement with those reported by other authors (Apple et al., 2005; Becerra et al., 2007; de Oliveira and Oliveira, 2005), who found that in well-drained soils the highest percentage of AMF colonization occurred during the rainy season. Newhall and Berdanier (1996) pointed out that roots are subjected to strong hydric and nutritional stresses related to changes in soil water content, which negatively affect mycorrhizal colonization.

This work confirms the association of I. paraguariensis with AMF, showing that yerba mate is a host species under both crop and natural conditions. The results also show that the percentages of arbuscular colonization decrease when the tillage practices are more intense. Considering the current progress on the knowledge of mycorrhizal associations in crops of yerba mate, it is necessary to develop a methodology aimed at protecting and maximizing the benefits of the symbiosis with these microorganisms that are naturally and evolutionary associated with yerba mate.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by Agencia de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 0677-Préstamo BID), CICPBA, and Universidad Nacional de La Plata (11/N 773).

MSV, MC and JCF conceived and designed research. JCF conducted fiel sampling. MSV, NA, JCF and CLA conducted laboratory experiments. MSV, NA, MC and JCF analyzed data. MSV wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Biofertilizer of organic coffee in stage of seedlings in Chiapas, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 2011;2(3):417-431.

- [Google Scholar]

- La biofertilización del cacao (Theobroma cacao) L. en vivero con Azospirillum brasilense Tarrand, Krieg et Döbereiner y Glomus intraradices Schenk et Smith. Interciencia. 2007;32(8):1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hongos endomicorrízicos y bacterias fijadoras de nitrógeno inoculadas a Coffea arabica en vivero. Agronomía Mesoamericana. 2011;22(1):71-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycorrhizal status of some plants of the Araucaria forest and the Atlantic rainforest in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Mycorrhiza. 2000;10(3):131-136.

- [Google Scholar]

- The potential of beneficial microorganisms in agricultural systems. Ann. Appl. Biol.. 2012;160(1):1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of Larrea tridentate and Ambrosia dumosa roots varies with precipitation and season in the Mojave Desert. Symbiosis. 2005;39(3):131-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycorrhiza and their significance on nodulating nitrogen fixing plants. Adv. Agron.. 1983;36:1-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of vascular plants from the Yungas forest, Argentina. Ann. For. Sci.. 2007;64(7):765-772.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the diversity of the root-associated microbiome of Ilex paraguariensis St. Hil. (Yerba Mate) Appl. Soil. Ecol.. 2017;109:23-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seasonal dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in differing wetland habitats. Mycorrhiza. 2004;14(5):329-337.

- [Google Scholar]

- Six-year fertilization modifies the biodiversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in a temperate steppe in Inner Mongolia. Soil Biol. Biochem.. 2014;69:371-381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Colozzi-Filho, A., Siqueira, J.O., 1986. Micorrizas vesículo-arbusculares em mudas de cafeeiro. I. Efeitos de Gigaspora margarita e adubação fosfatada no crescimento e nutrição. Rev Bras Ciênc Solo 10(3) 199–206.

- Elementos Minerales y Carbohidratos en plantones de aguacate “Carmen” inoculados con micorrizas arbusculares. Actas V Congreso Mundial del Aguacate 2003:415-420.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seasonal dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plants of Theobroma grandiflorum Schum, and Paullina cupana Mart. of an agroforestry system in Central Amazonia, Amazonas State, Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol.. 2005;36(3):262-270.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mapa de Suelos de la Provincia de Corrientes. INTA, Subsecretaría de Recursos Naturales y Medio Ambiente: Corrientes, Argentina; 1996.

- Ocurrence of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in erva-mate (Ilex paraguarienses St. Hil.) Boletim de Pesquisa Florestal, Colombo. 1980;12:21-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Agroecology: the key role of arbuscular mycorrhizas in ecosystem services. Mycorrhiza. 2010;20(8):519-530.

- [Google Scholar]

- Goss, M.J., Carvalho, M., Brito, I., 2017. The Significance of an Intact Extraradical Mycelium and Early Root Colonization in Managing Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. In: Functional Diversity of Mycorrhiza and Sustainable Agriculture - Management to Overcome Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Academic Press, pp. 111–130.

- Disentangling the impact of AM fungi versus roots on soil structure and wáter transport. Plant Soil. 2009;314(1–2):183-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycorrhizal relations in trees for agroforestry and land rehabilitation. Forest Ecol. Manag.. 1996;81(1–3):1-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduced 15N nitrogen transport through arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphae to Triticum aestivum L. supplied with ammonium vs. nitrate nutrition. Ann. Bot.. 2001;87:302-311.

- [Google Scholar]

- INYM, 2011. El consumo de yerba mate en Argentina. Instituto Nacional de la Yerba Mate. http://inym.org.ar. 4 Apr. 2017

- Jackson, M.L., 2005. Soil chemical analysis: Advanced course. UW-Madison Libraries Parallel Press.

- Arbuscular mycorrhizal mediated nutrition in plants. J. Plant Nutr.. 2009;32(10):1595-1618.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jodice, R., Nappi, P., 1987. Microbial aspects of compost application in relation to mycorrhizae and nitrogen fixing microorganisms. In: Bertoldi M., Ferranti M.P., Hermite PL, Zucconi F. (eds.). Compost: production, quality and use. Italy, pp. 115–125.

- Variable response of growth and arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of maize plants to preceding crops in various types of soils. Biol Fert. Soils. 2001;33(4):286-293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis is accompanied by local and systemic alterations in gene expression and an increase in disease resistance in the shoots. Plant J.. 2007;50(3):529-544.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol.. 1990;115(3):495-501.

- [Google Scholar]

- Montañez Orozco, I., Vargas Sarmiento, C., Cabezas Gutiérrez, M., Cuervo Andrade, J., 2010. Colonización Micorrícica en plantas de aguacate (Persea americana L.). Revista U.D.C.A. Actualidad y Divulgación Científica 13(2) 51–60.

- Caracterización espacial-temporal de la micorriza nativa de dos plantaciones de cafeto en Cuba. Cultivos Tropicales. 2005;26(4)

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycorrhizal infection, phosphorus uptake, and phenology in Ranunculus adoneus: implications for the functioning of mycorrhizae in alpine systems. Oecologia. 1993;94(2):229-234.

- [Google Scholar]

- Calculation of soil moisture regimes from the climatic record. Soil Survey Investigation Report: NRCS; 1996.

- Field inoculation effectiveness of native and exotic arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in a Mediterranean agricultural soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43(2):367-376.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluación de la colonización de micorrizas arbusculares en pasto Bothriochloa pertusa. Revista MVZ. 2010;15(3):2165-2174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved procedure for clearing root and staining parasitic and VA-mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. T Brit. Mycol. Soc.. 1970;55(1):158-161.

- [Google Scholar]

- Linear mixed-effects models: basic concepts and examples. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-Plus 2000:3-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arbuscular mycorrhizal influence on leaf water potential, solute accumulation, and oxidative stress in soybean plants subjected to drought stress. J. Exp. Bot.. 2004;55(403):1743-1750.

- [Google Scholar]

- A gene from the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices encoding a binding protein is up-regulated by drought stress in some mycorrhizal plants. Environ. Exp. Bot.. 2007;60(2):251-256.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycorrhizal symbiosis (3rd ed). London: Academic Press; 2008.

- A phylum-level phylogenetic classification of zygomycete fungi based on genome-scale data. Mycologia. 2016;108(5):1028-1046.

- [Google Scholar]

- A meta-analysis of mycorrhizal responses to nitrogen, phosphorus, and atmospheric CO2 in field studies. New Phytol. 2004;164(2):347-355.

- [Google Scholar]

- An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci.. 1934;37(1):29-38.

- [Google Scholar]