Translate this page into:

Chemical composition and mosquitocidal efficacy of panchagavya against Anopheles stephensi, Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus

⁎Corresponding authors at: Nano and Energy Bioscience Laboratory, Department of Biotechnology, Thiruvalluvar University, Serkkadu, Vellore - 632115, Tamil Nadu, India. babukmg@gmail.com (Ranganathan Babujanarthanam)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

The current study looks towards reporting the chemical compounds present in the panchagavya (PG), free radicals scavenging and mosquitocidal activity of PG in the laboratory condition.

Methods

The existence of chemical compounds in the PG were studied by GC–MS analysis. Free radicals scavenging activity of PG was studied by using various invitro assays. Mosquitocidal efficacy of PG was studied by the experiment on larvicidal, pupicidal, adulticidal, fecundity, longevity, and ovicidal activity against An. stephensi, Ae. aegypti and Cx. quinquefasciatus.

Results

GC–MS analysis revealed fifteen chemical compounds present in the PG. Free radical scavenging was done by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid), hydroxyl, and superoxide assays, and the IC50 was calculated as 37, 37.5, 35, and 38 μg/mL respectively. PG exhibited better larvae and pupae mortality against I-IV instar of Cx. quinquefasciatus (LC50: 148.765, 162.534, 187.619, 210.835 and 234.624 ppm, LC90: 286.636, 306.390, 350.276, 390.735 and 419.195 ppm). The highest adult mortality was found against An. stephensi (91.10 ± 1.74%) with the IC50 and IC90 values of 128.114 and 260.609 ppm. An. stephensi showed highly decreased fecundity and longevity even at a low concentration of PG. Inhibition of 100% egg hatchability of An. stephensi was obtained at 250 ppm followed by Ae. aegypti, and Cx. quinquefasciatus at 300 ppm respectively. On comparing with other mosquito vectors An. stephensi was effectively inhibited by PG at each stage of their life cycle.

Conclusion

The results provide the first proof that PG could be a successful natural agent for controlling different mosquito vectors. Furthermore, our findings pave the way for more research into the efficacy of natural materials' mosquitocidal activities.

Keywords

Panchagavya

Superoxide

Mosquito vectors

I-IV instar

An. stephensi

1 Introduction

Mosquitoes are one of the most significant risks to public safety in the world, as they are carriers of many pathogenic micro-organisms that cause various human diseases and those diseases are endangering human life and contributing to multiple morbidities and high mortality (Huang et al., 2019). Mosquito-borne diseases are widespread in more than 100 countries, triggering deaths of about 2 million people worldwide, and at least 1 million children suffer from mosquito-borne diseases per year, endangering as much as 2.1 billion people worldwide. In India, 17 states and 6 territories of the country have been identified as endemic, with about 553 million citizens at risk of mosquito-borne diseases (Elumalai et al., 2016).

The genera Anopheles, Aedes, and Culex mosquito species are carriers of various diseases, such as Japanese encephalitis, filariasis, malaria, chikungunya, dengue, and yellow fever (Benelli and Duggan, 2018). Anopheles mosquitoes are classified as human malaria vectors, filariasis, and some arboviruses and they exist nearly all over the world, except cold temperate areas and there are over 400 known species. Malaria appears to be one of the largest communicable diseases, which results in 300–500 million malaria cases per annum (Kesete et al., 2020). Aedes mosquitoes are painful and persistent biters. These mosquitoes are run sporters of dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, and Zika viruses. One estimated prediction indicates that 3.9 billion dengue virus infections occurred on an annual basis, and from that, 0.096 billion are clinically expressed with disease severity. Another research on dengue incidence reports that 3.9 billion peoples are at danger of dengue virus infections (Waggoner et al., 2016). Cx. quinquefasciatus is an existing domestic mosquito related to human dwelling and activity. Cx. quinquefasciatus can spread many pathogenic agents like the West Nile virus, lymphatic filariasis, and Saint Louis encephalitis to humans and animals (Guta et al., 2021). Cx. quinquefasciatus may also cause avian malaria to cattle, insects, birds, sheep, cows, and wild animals which results in productivity loss and death (Sutthanont et al., 2019).

For several decades, the transmission chain of vector-borne diseases was broken by using synthetic insecticidal chemicals although, frequent use of synthetic insecticidal chemicals causes less effectiveness and ecological problems such as mosquito tolerance, ecological disturbance, and fallout to mammals (Chareonviriyaphap et al., 2013; Pavela 2008; Rahuman et al., 2008). Therefore, the hazards of synthetic insecticidal chemicals must be stabilized towards humans, wildlife, and non-target organisms. The effects of synthetic insecticidal agents, as well as mosquito tolerance, have prompted the hunt for novel insecticidal agents (Zaim and Guillet 2002; Thomas et al., 2004). To produce new insecticidal substances, we use the novel and effective product with insecticidal properties from the cow namely “panchagavya” (PG) to control various genera of mosquito. PG is an organic formulation, produced by combining five cow products i.e. dung, urine, milk, ghee, and curd. The components like cow dung and cow urine enhance the insecticidal activity of PG (Shailaja et al., 2014). It is already reported that cow urine and cow dung have larvicidal activity (Kumar et al., 2009; Ngugi 2009) and, PG has insecticidal and larvicidal activity (Sayi et al., 2018).

Therefore, the current research focused on preparation of PG, identification of the chemical compounds present in the PG, evaluation of its free radical scavenging activity, and the mosquitocidal efficiency by performing various mosquitocidal assays like larval and pupal toxicity, adulticidal, longevity, fecundity, and ovicidal assays.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of PG

By using the Sathiyaraj et al. (2021) method, PG was prepared with some alterations. For the preparation of PG, 1 kg of indigenous cow dung, 300 g of ghee, 1 L of indigenous cow milk, 1 L of indigenous cow urine, 1 L of curd, ½ L of tender coconut water, 1 kg of jaggery, 6 number of ripened bananas, and water were added to the wide-mouthed container. The container was stirred twice a day and kept in the shade until the end of the process. Then the prepared PG was filtered in blotting paper and used for future studies.

2.2 Gas chromatography - mass spectroscopy (GC–MS) analysis

The components were separated using Helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min on a Perkin Elmer Clarus 680 GC with a fused silica column packed with Elite-5MS (5% biphenyl, 95% dimethylpolysiloxane, 30 m 0.25 mm ID 250 m df). The injector temperature was set at 260 °C during the chromatographic process. 1 µL of PG was injected into the instrument, and the oven temperature was set to 60 °C for 2 min, followed by 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C for 1 min, and 300 °C for 6 min. The mass detector was set up with the following parameters: 230 °C transfer line, 230 °C ion source, 70 eV electron ionisation mode impact, 0.2 sec scan time, 0.1 sec scan interval, and fragments ranging from 40 to 600 Da. The component spectrums were compared to the GC–MS NIST library's spectra database of known components (2008).

2.3 Free radicals scavenging activity

2.3.1 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)

The free radicals scavenging activity of PG against DPPH was performed by the method described previously (Sathiyaraj et al., 2020). 1 mL of PG at various concentrations (0, 10, 20, 30, 40 & 50 µg/mL) was blended with newly prepared DPPH solution (1 mL) and it was placed in the dark at 37 ℃ for 30 min. After incubation, scavenging activity was calculated based on the absorbance of the sample using UV spectrophotometry at 518 nm and it was compared with vitamin C. The scavenging activity of PG was studied by using formula 1.

2.3.2 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTs) assay

The method previously described was used to investigate ABTs scavenging activity of PG (Suriyakala et al., 2021). The reaction between 7 mM ABTS in distilled H2O and 2.45 mM K2S2O8 creates the ABTs cation radical, which was deposited in the dark for 12–16 h at room temperature before use. After then, the ABTs radical solution was mixed with methanol to obtain a 0.700 absorbance at 734 nm. The absorbance was measured 30 min after the initial mix with the addition of 1 mL of various PG concentrations. Formula 1 was used to get the percent absorbance inhibition at 734 nm. The same was done for vitamin C, which is utilised as a standard control, for comparison.

2.3.3 Hydroxyl radical (OH−) scavenging assay

The approach described by Pavithra and Vadivukkarasi (2015) was used to investigate the PG's OH-scavenging activity. 1.0 mL of PG (0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µg/mL), iron-EDTA solution (1.0 m), 0.018% EDTA (0.5 ml), DMSO (0.1 ml), and 0.22% vitamin C (1 mL) were included in the reaction mixture. Using a water bath, the reaction was heated to 80–90 °C for 15 min before being stopped by the addition of ice-cold TCA (1 mL). 3.0 ml Nash reagent was added to the reaction mixture and allowed to set at room temperature for 15 min before testing for color production. UV spectroscopy was used to measure the intensity of the yellow colour that developed at 412 nm. Formula 1 was used to calculate the OH− scavenging activity, which was then compared to vitamin C.

2.3.4 Superoxide (O2−) radical scavenging assay

The ability of PG to scavenge superoxide radicals was investigated using the previously established method of depletion of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) (Pradhan et al., 2021). 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 73 mM nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, 50 mM NBT, 15 mM phenazine methosulfate, and various doses of PG (0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µg/mL) are included in the 1 mL reaction. The reaction mixture was left at room temperature for 5 min and the absorbance was measured at 562 nm. The reaction content's absorbance was compared to that of vitamin C, and the O2− scavenging activity was estimated using formula 1.

2.4 Mosquitocidal bioassays

All the mosquitocidal bioassays were carried out in the laboratory-reared mosquito vectors, without exposure to pesticides and disease-causing organisms. The selected mosquito species were reared to attain larval hatching by the previously described method (Thomas et al., 2017).

2.4.1 Larvicidal and pupicidal assays

The larvicidal and pupicidal assays using PG were performed by the standard procedures suggested by (Kovendan et al., 2012). Twenty-five numbers of I-IV instar of selected larvae and pupae were added to a beaker containing 2 mL of desired concentration of PG and 248 mL of dechlorinated water and it was checked for mortality. At each desired concentration the experiment was three times replicated. The larvae and pupae were treated with 248 mL of dechlorinated water and 2 mL of acetone which was used as control. Percent mortality was calculated by formula 2,

2.4.2 Adulticidal assay

The adulticidal assay using PG was examined by the method suggested by Ejeta et al. (2021). 2 mL of varying concentrations (50, 100, 150, 200 & 250 ppm) of PG was applied on the filter paper and it could dry completely. The dried filter paper was introduced into an exposure tube in the WHO testing kit. A whole 25 number of 2–5 days old, blood-unfed female mosquitoes were inserted into the holding tube and retained for 1 h to adapt to the condition. Then the mosquitoes were transported in the exposure tube by gentle blowing and retained for an acclimatization period of 1 h. Then the mosquitoes were got back to the holding tube and transferred to a petri-dish containing cotton pad soaked with a 10% C6H12O6 solution for the recovery of mosquitoes. The number of dead mosquitoes was registered at 24-hours of the recovery period, and the percentage mortality was estimated. At the same time control was made by using acetone as well as experiment was replicated three times.

2.4.3 Fecundity and longevity studies

The fecundity and longevity of the selected mosquito species were studied by the methodology suggested by (Nareshkumar et al., 2012). The mosquito fecundity was checked by picking an equivalent number of male and female mosquito larvae from the control and treated using PG. From each concentration, these mosquitoes were separately placed in 30 × 30 cm cages. Three days followed by the blood meal; eggs were collected regularly from tiny plastic bowls that hold water contained in an ovitrap in the cages. Fecundity was determined from the number of eggs laid in an ovitrap, separated by the individuals of females mated. Consideration has been granted to adult mortality in such studies. Adult longevity of male and female mosquitoes was calculated according to the number of days the adult mosquitoes lived. A total number of days were recorded from adult emergence to death and the means were calculated to give the average longevity within days.

2.4.4 Ovicidal activity

The method from Torawane et al. (2021) was used and applied with some modification for ovicidal activity. A total of 100 Eggs of the chosen mosquito species were subjected to different concentrations of PG (50, 100, 150, 200, 250 & 300 ppm). After 24 h of examination, the eggs were counted using a microscope and the eggs were separately taken, then transferred to a beaker containing demineralized water for egg hatching evaluation. The process was triplicated along with proper control. After 48 h of PG exposure, the egg hatchability was calculated by formula 3,

2.5 Data analysis

The LC50, LC90, and other statistics were calculated using the mean mortality data at 95% upper and lower fiducial limits. The chi-square values were calculated using the statistical software SPSS (version 25). Statistically significant results are those with a P value of less than 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 GC–MS analysis

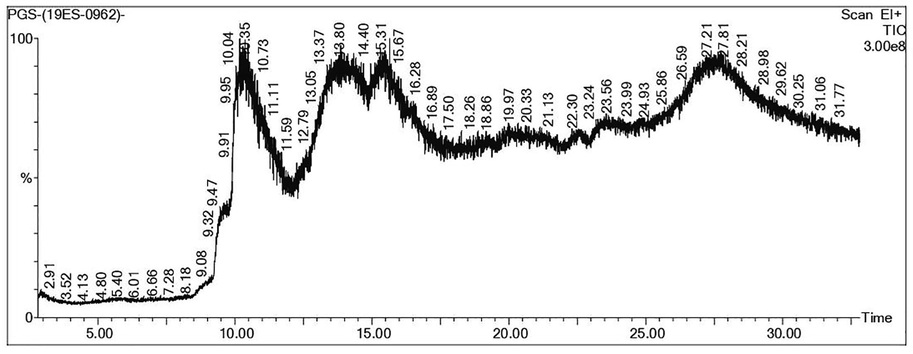

In the GC–MS analysis, 15 different compounds were obtained, and the chromatogram was given in Fig. 1. The compounds Retention Time (RT), Peak Area (%), and biological activities have been presented in Table 1.

GC–MS chromatogram of PG.

S. No

Retention Time

% Area

Compound

Biological activity

Reference

1

9.951

3.628

Paraldehyde

Anticonvulsant activity, Anti-HIV activity

Rowland et al., 2009; Flavin et al., 1996

2

10.041

14.483

1,2-propanediol diformate

No biological activity reported

–

3

10.176

10.233

Acetaldehyde, tetramer

No biological activity reported

–

4

10.236

8.017

Paraldehyde

Anticonvulsant activity, Anti-HIV activity

Rowland et al., 2009; Flavin et al., 1996

5

10.291

4.617

Ethene, 1,1′-[oxybis(2,1-ethanediyloxy)]bis

No biological activity reported

–

6

10.371

10.385

Butanoic acid, 3-hydroxy-, ethyl ester, (.+/-.)-

Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, Anticancer, antiarthritic, antihistimic, antieczemic, and anticoronary activities

Kumar et al., 2010

7

10.477

13.685

2-butanol, 3-chloro

No biological activity reported

–

8

10.632

2.551

Methoxyacetic acid, butyl ester

Antimicrobial activity

Ganesh and Mohankumar 2017

9

14.723

2.325

1-methyl-1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-silacyclobutane

No biological activity reported

–

10

15.519

3.070

Butanamide, 3,n-dihydrox-

No biological activity reported

–

11

15.699

5.301

Propanoic acid, 3-methoxy-, methyl ester

Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, nematicide, pesticidal activities

Mahalakashmi and Thangapandian 2019

12

26.758

2.594

Cholest-5-en-3-ol (3.beta.)-, acetate

No biological activity reported

–

13

27.353

2.546

2,3-o-benzal-d-mannosan

No biological activity reported

–

14

27.629

10.816

Di-n-propylmalonic acid

No biological activity reported

–

15

27.999

5.751

Pseduosarsasapogenin-5,20-dien methyl ether

No biological activity reported

–

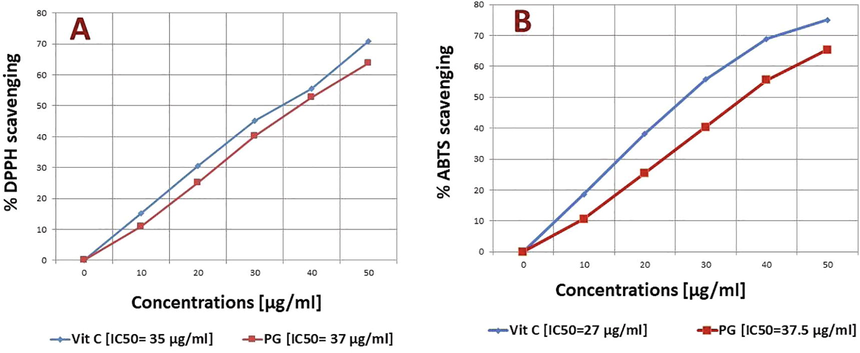

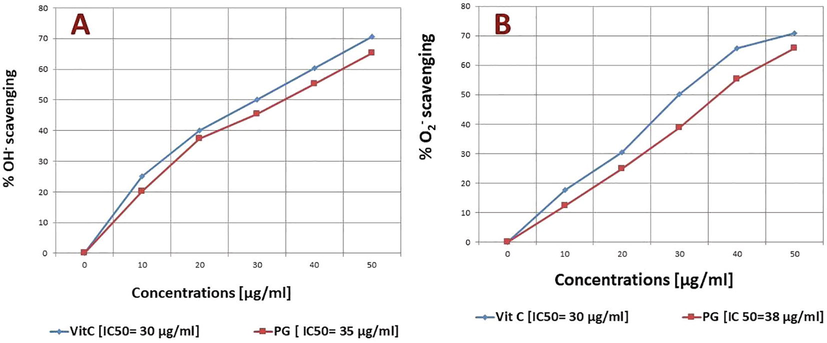

3.2 Free radicals scavenging activity

DPPH, ABTs, OH− and O2− are the typical reactive oxygen species (ROS), which trigger diseases linked to oxidative stress. PG effectively scavenged all four ROS and the percent inhibition was raised in a concentration-dependent way. The IC50 of PG was found to be 37, 37.5, 35, and 38 μg/mL respectively on DPPH, ABTs, OH− and O2−. The results of PG were compared with standard control at each concentration (Figs. 2 & 3).

Free radicals scavenging at different concentrations A) DPPH B) ABTs.

Free radicals scavenging at different concentrations A) OH− B) O2−.

3.3 Mosquitocidal bioassays

Under the in-vitro condition, PG was found to be toxic towards I-IV instar of larvae and pupae of An. stephensi, Ae. aegypti and Cx. Quinquefasciatus (Table 2). The LC50 of I-IV instar of An. Stephensi was found to be 121.991, 146.723, 166.471, 192.303, and 216.687 ppm (Pupae) respectively. The LC90 of I-IV instar of larvae and pupae of An. stephensi was found to be 246.063, 286.663, 327.514, 375.741, and 411.457 ppm (Pupae) respectively. The LC50 of I-IV instars of Ae. aegypti recorded as follows: 129.754, 153.531, 179.644, 203.369 and 298.276 ppm (pupae) and LC90 was found to be 258.552, 297.332, 344.920, 391.304 and 424. 610 ppm (pupae) respectively. The LC50 of I-IV instar of Cx. quinquefasciatus was noted as follows: 148.765, 162.534, 187.619, 210.835, and 234.624 ppm (Pupae), and the LC90 was found to be 286.636, 306.390, 350.276, 390.735, and 419.195 ppm (Pupae) respectively. After 24 h exposure of adulticidal mosquitoes to 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 ppm concentration of PG, it was found that PG exhibited high toxicity to the selected adult mosquito vectors however, the highest mortality was found against An. stephensi (91.10 ± 1.74%) with the IC50 and IC90 values of 128.114 and 260.609 ppm followed by Ae. aegypti (88.86 ± 1.50%) and Cx. quinquefasciatus (85.70 ± 1.41%) with the IC50 and IC90 values of 135.179, 144.336 ppm and 272.575, 283.066 ppm respectively (Table 3). LC50 = Lethal concentration that kills 50% of the exposed mosquito species. LC90 = Lethal concentration that kills 90% of the exposed mosquito species. LCL = Lower Confidence Limit. UCL = Upper Confidence Limit. χ2 = chi-square. n.s. = not significant (α = 0.05). The findings were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. According to Duncan's technique, the values and a-e superscripts are significantly different from each other (p = 0.05). n.s. = not significant (α = 0.05).

Mosquito species

Target

LC50 (LC90) (ppm)

95% confidence Limit

Regression equation

χ2 (df = 4)

LC50 (LC90)

LCL

UCL

Anopheles stephensi

I instar

121.991

(246.063)109.007

(226.351)133.813

(273.033)

y = 1.260 + 0.010x

4.311n.s.

II instar

146.723

(286.663)133.517

(261.212)159.837

(322.918)

y = 1.344 + 0.009x

4.887n.s.

III instar

166.471

(327.514)151.830

(293.769)182.445

(378.308)

y = 1.325 + 0.008x

2.727n.s.

IV instar

192.303

(375.741)175.078

(330.398)213.970

(448.581)

y = 1.343 + 0.007x

2.530n.s.

Pupa

216.687

(411.457)196.404

(356.910)245.310

(502.949)

y = 1.426 + 0.007x

1.128n.s.

Aedes aegypti

I instar

129.754

(258.552)116.783

(237.292)141.845

(287.965)

y = 1.291 + 0.010x

3.823n.s.

II instar

153.531

(297.332)140.173

(270.208)167.179

(336.351)

y = 1.368 + 0.009x

3.928n.s.

III instar

179.644

(344.920)164.446

(307.920)197.346

(401.489)

y = 1.393 + 0.008x

2.802n.s.

IV instar

203.369

(391.304)184.969

(342.179)227.793

(471.601)

y = 1.387 + 0.007x

1.803n.s.

Pupa

228.276

(424.610)206.449

(366.883)260.330

(522.613)

y = 1.490 + 0.007x

2.162n.s.

Culex quinquefasciatus

I instar

148.765

(286.636)135.789

(261.533)161.757

(322.244)

y = 1.383 + 0.009x

4.942n.s.

II instar

162.534

(306.390)149.272

(278.244)176.597

(347.053)

y = 1.448 + 0.009x

2.053n.s.

III instar

187.619

(350.276)172.326

(312.912)206.000

(407.287)

y = 1.478 + 0.008x

2.978n.s.

IV instar

210.835

(390.753)192.462

(343.182)235.590

(467.437)

y = 1.502 + 0.007x

2.716n.s.

Pupa

234.624

(419.195)213.096

(364.682)266.167

(509.933)

y = 1.629 + 0.007x

1.807n.s.

Mosquito species

Concentration (ppm)

Mortality (%) (mean ± SD)

LC50 ppm (LCL-UCL)

LC90 ppm (LCL-UCL)

χ2 (df = 3)

Anopheles stephensi

Control

50

100

150

200

2500.00 ± 0.00

26.84 ± 1.59e

33.98 ± 1.33d

58.64 ± 1.21c

72.68 ± 1.47b

91.10 ± 1.74a

128.114

(114.674–140.511)260.609

(238.694–291.155)3.615n.s

Aedes aegypti

Control

50

100

150

200

2500.00 ± 0.00

25.70 ± 1.46e

32.38 ± 1.62d

54.52 ± 1.04c

70.38 ± 1.67b

88.86 ± 1.50a

135.179

(121.690–147.932)272.575

(248.926–305.943)3.190n.s

Culex quinquefasciatus

Control

50

100

150

200

2500.00 ± 0.00

22.94 ± 1.73e

29.92 ± 1.85d

50.62 ± 1.66c

68.84 ± 1.62b

85.70 ± 1.4a

144.336

(131.129–157.285)283.066

(258.283–318.191)2.148n.s

Adult longevity and fecundity of the selected mosquito vectors using PG were given in Table 4. When compared with control, a great significant result was observed in the longevity and fecundity of the selected mosquito vectors. Longevity of male mosquitoes of An. Stephensi was found to be 22.2 days (d), 18.4 d, 14.6 d, 10.2 d, 07.4 d, and in the longevity of male mosquitoes of An. Stephensi was found to be 26.3 d, 22.2 d, 14.1 d, 12.4 d, and 08.1 d respectively on 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 ppm, whereas control showed 26.0 d in males and 35.0 d in females for adult longevity. After exposure of PG, the fecundity of An. stephensi also reduced as follows: 126.2, 107.2, 96.4, 77.2, and 55.8 at 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 ppm respectively. The findings were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. According to Duncan's technique, the values with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (p = 0.05).

Treatment (ppm)

Adult longevity (days)

Fecundity (no. eggs)

Male

Female

Control

26.0 ± 0.61a

35.0 ± 0.70a

146.0 ± 0.64a

Anopheles stephensi

50

21.4 ± 1.14b

29.2 ± 1.48b

131.7 ± 1.70b

100

18.6 ± 1.51c

23.7 ± 0.95c

128.2 ± 0.83c

150

17.4 ± 2.50d

18.2 ± 0.83d

115.2 ± 1.78d

200

12.6 ± 0.89e

15.4 ± 1.14e

101.8 ± 1.09e

250

9.2 ± 0.44f

11.2 ± 1.30f

99.4 ± 1.51f

Aedes aegypti

Control

26.0 ± 0.61a

35.0 ± 0.70a

146.0 ± 0.64a

50

25.6 ± 1.67b

32.8 ± 1.64b

136.8 ± 1.30b

100

22.8 ± 1.48c

25.8 ± 0.44c

132.5 ± 0.91c

150

19.2 ± 1.09d

22.7 ± 0.44d

128.9 ± 1.67d

200

13.8 ± 1.48e

18.6 ± 1.51e

117.4 ± 1.51e

250

10.1 ± 0.93f

13.8 ± 1.09f

103.0 ± 1.87f

Culex quinquefasciatus

Control

26.0 ± 0.61a

35.0 ± 0.70a

146.0 ± 0.64a

50

27.2 ± 1.92b

34.2 ± 0.44b

133.6 ± 1.81b

100

24.4 ± 2.07c

29.6 ± 1.51c

130.4 ± 2.50c

150

20.4 ± 1.81d

25.0 ± 0.57d

129.4 ± 1.51d

200

17.4 ± 1.14e

21.2 ± 0.44e

125.8 ± 0.83e

250

13.1 ± 0.77f

19.6 ± 0.89f

108.8 ± 1.64f

Adult longevity of Ae. aegypti (males) was noted as follows 23.8 d, 19.2 d, 15.4 d, 12.5 d, 09.3 d, and the longevity of Ae. aegypti in females was noted as 30.2 d, 24.6 d, 18.9 d, 15.4 d, 10.2 d at 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 ppm respectively. Here 27.0 d in males and 35.0 d in females was observed for adult longevity of control. After exposure of PG, the fecundity of Ae. aegypti also reduced as follows: 127.8, 112.2, 95.2, 73.6, and 57.4 at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 ppm respectively.

Adult longevity of Cx. quinquefasciatus in males, after exposure of PG, was found to be 23.3 d, 20.5 d, 18.7 d, 12.1 d, 10.1 d and in females exhibited as follows 31.2 d, 23.3, 17.0 d, 14.4 d, 12.3 d at 50, 100, 150, 200 and 250 ppm whereas control showed 26.0 d in males and 35.0 d in females. After exposure of PG, the fecundity of Cx. quinquefasciatus also reduced as follows: 130.8, 111.2, 92.0, 74.6, and 59.6 at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 ppm respectively. The ovicidal activity of different concentrations of PG (50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 ppm) on tested mosquito species was presented in Table 5. PG efficiently inhibits the 100% egg hatchability of An. stephensi, Ae. aegypti and Cx. Quinquefasciatus at 250 ppm, 300 ppm, and 300 ppm respectively. The findings were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Significantly differed values were mentioned with a-e superscripts according to Duncan's method (p = 0.05). NH – no hatchability.

Mosquito species

Egg hatchability (%)

Concentration (ppm)

Control

50

100

150

200

250

300

Anopheles stephensi

100

±0.0a

58.8

±1.92b

39.6

±1.14c

25.6

±1.51d

11.4

±1.81e

NH

NH

Aedes aegypti

100

±0.0a

60.2

±1.78b

41.4

±1.81c

27.6

±1.94d

13.4

±1.14e

07.0

±1.58f

NH

Culex quinquefasciatus

100

±0.0a

61.6

±1.67b

40.0

±1.58c

28.8

±1.30d

15.2

±1.78e

09.6

±1.14f

NH

4 Discussion

4.1 Compounds in the PG

The compounds identified in the PG are; paraldehyde; 1,2-propanediol diformate; acetaldehyde, tetramer; paraldehyde; ethene, 1,1′-[oxybis(2,1-ethanediyloxy)]bis; butanoic acid, 3-hydroxy-, ethyl ester, (.+/−.)-; 2-butanol, 3-chloro; methoxyacetic acid, butyl ester; butanamide, 3,n-dihydrox-; propanoic acid, 3-methoxy-, methyl ester; cholest-5-en-3-ol (3.beta.)-, acetate; 2,3-o-benzal-d-mannosan; di-n-propylmalonic acid; pseduosarsasapogenin-5,20-dien methyl ether. These compounds possess various biological activities including anti-HIV, anti-cancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, nematicide, and pesticidal activities (Rowland et al., 2009; Flavin et al., 1996; Kumar et al., 2010; Ganesh and Mohankumar 2017; Mahalakashmi and Thangapandian 2019).

4.2 Free radicals scavenging activity

Based on free radicals scavenging results, the PG scavenges toxic free radicals, and it can protect the free radicals from adverse effects. Both hydrophilic and hydrophobic antioxidants are present among naturally occurring antioxidants. Ascorbic acid, α-lipoic acid, bioflavonoids, polyphenols, and glutathione are the main hydrophilic antioxidants while vitamin E, α- tocopherol, co-enzyme Q10, Total carotenoids, and Lycopene are the hydrophobic antioxidants (Lazzarino et al., 2019). Free radicals are produced in both water and fat portions in intracellular and extracellular environments; hence, a mixture of hydrophilic and hydrophobic antioxidants is essential for the body to achieve the maximum spectrum of protection. Certain antioxidants are synthesised by the body, while others are obtained from external sources such as milk and nutraceuticals. Panchagavya is a unique blend of water-based (fat-free colloidal milk, curd, urine, and dung) and fat-based materials (ghee, fat-particulate milk). This is likely to provide natural antioxidants which are both polar and non-polar. The data of the free radicals scavenging activity of PG reveals that the PG act as an excellent antioxidant. Athavale et al. (2012) evaluated the free radicals scavenging activity of PG and the results of the DPPH assay and superoxide assay were agreed with our findings. Previous studies confirmed that cow urine and cow dung alone have free radical scavenging activity (Jarald et al., 2008; Jirankalgikar et al., 2014), when it is used in a combination it exhibits an exceptional free radical scavenging activity.

4.3 Mosquitocidal activity

Synthetic insecticides have been employed against mosquito vectors over the last 5 decades. Therefore, side effects such as environmental contamination and toxic hazards towards humans and other non-target species were developed. Such side effects of synthetic insecticides provided recognition of the requirement for mosquito control which is eco-friendly, biodegradable, target-specific, and indigenous material (Reegan et al., 2015; Amerasan et al., 2015). The development cycle of a mosquito represents the egg, larvae, pupae, and adult stage. To control the mosquito population, kill them at egg and larvae stages, which is more effective compared to targeting the free-flying adult mosquitoes (Carvalho et al., 2003). Here we are using PG, formulated from indigenous material for mosquito control. PG potentially acts against mosquitoes not only at the larval stage but also includes each development stage of mosquitoes. Our findings of larvicidal, pupicidal, adulticidal, fecundity, longevity, and ovicidal activity of PG on I to IV instar of selected mosquito vectors showed proof of a lethal effect, and mortality was dose dependent. Kumar et al. (2009) tested the larvicidal activity of cow urine against Cx. quinquefasciatus at 5% and they obtain 95% mortality on the 3rd day. There are few reports were available on cow dung as a mosquito repellent (Sharma et al., 2017; Mandavgane et al., 2005). There are no references available in the literature related to mosquitocidal studies on PG and a few cow products. Hence, this study will be established as a future reference for further investigations on PG and cow products.

5 Conclusion

In the present study, fifteen chemical compounds have been identified from PG by GC–MS analysis and these compounds have various biological activities. Further, PG possesses excellent free radical scavenging and mosquitocidal properties. Our results confirm that the PG is toxic towards An. stephensi, Ae. aegypti and Cx. Quinquefasciatus at each stage of their life cycle. It was concluded that PG is often very effective against a specific target, less costly, effortlessly biodegradable and it could be a substitute for synthetic insecticides for mosquito vector control.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for funding this research through Researchers Supporting Project No. (RSP2022R465). Also authors thank the University of Douala, Cameroon, for the support and encouragement.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Bioefficacy of Morinda tinctoria and Pongamia glabra plant extracts against the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) J. Entomol Acarol Res.. 2015;47:31-40.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of in-vitro antioxidant activity of panchagavya: a traditional ayurvedic preparation. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res.. 2012;3:2543-2549.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of arthropod vector data–Social and ecological dynamics facing the One Health perspective. Acta. Trop.. 2018;182:80-91.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity of the essential oil from Lippia sidoides Cham. against Aedes aegypti Linn. Mem. I. Oswaldo. Cruz. 2003;98:569-571.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review of insecticide resistance and behavioral avoidance of vectors of human diseases in Thailand. Parasit. Vectors. 2013;6:280.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Insecticidal effect of ethnobotanical plant extracts against Anopheles arabiensis under laboratory conditions. Malar. J.. 2021;20:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity of catechin isolated from Leucas aspera against Aedes aegypti, Anopheles stephensi, and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res.. 2016;115:1203-1212.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, chromatographic resolution, and anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity of (±)-calanolide A and its enantiomers. J. Med. Chem.. 1996;39(6):1303-1313.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraction and identification of bioactive components in Sida cordata (Burm. f.) using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Int. J. Food. Sci. Tech.. 2017;54:3082-3091.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Species composition, blood meal sources and insecticide susceptibility status of Culex mosquitoes from Jimma area, Ethiopia. Int. J. Trop. Insect. Sci.. 2021;41:533-539.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical composition and larvicidal activity of essential oils from herbal plants. Planta. 2019;250:59-68.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of cow urine. Global. J. Pharmacol.. 2008;2:20-22.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro antioxidant activity evaluation and HPTLC profile of Cow dung. Int. J. Green. Pharm.. 2014;8:158-162.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of malaria from blood smears examination: a three-year retrospective study from Nakfa Hospital, Eritrea. medRxiv 2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Studies on larvicidal and pupicidal activity of Leucas aspera Willd. (Lamiaceae) and bacterial insecticide, Bacillus sphaericus, against malarial vector, Anopheles stephensi Liston. (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res.. 2012;110:195-203.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Screening of antioxidant activity, total phenolics and GC-MS study of Vitex negundo. Afr. J. Biochem. Res.. 2010;4:191-195.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of Cow urine and Cow urine distillate as Larvicidal agents-an eco-friendly approach. Nat. Prod.. 2009;5:226-228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Water-and fat-soluble antioxidants in human seminal plasma and serum of fertile males. Antioxidants. 2019;8:96.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gas chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis of bioactive constituents of Maytenus heyneana (Roth) Roju & Babu (Celestraceae) J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem.. 2019;8:2748-2752.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of cow dung based herbal mosquito repellent. Nat. Prod. Rad.. 2005;4:270-272.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal potentiality, longevity and fecundity inhibitory activities of Bacillus sphaericus (Bs G3-IV) on vector mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Entomol. Acarol. Res.. 2012;44:e15

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ngugi, M.K., 2009. Effects of cow dung and selected medicinal plants on anopheles species as a strategy for malaria vector control in Ahero rice irrigation scheme, Kenya (Doctoral dissertation).

- Larvicidal effects of various Euro-Asiatic plants against Culex quinquefasciatus Say larvae (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res.. 2008;102(3):555-559.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of free radical scavenging activity of various extracts of leaves from Kedrostis foetidissima (Jacq.) Cogn. Food. Sci. Hum. Well.. 2015;4:42-46.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, B., Patra, S., Dash, S.R., Nayak, R., Behera, C., Jena, M., 2021. Evaluation of the anti-bacterial activity of methanolic extract of Chlorella vulgaris Beyerinck [Beijerinck] with special reference to antioxidant modulation. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 7, 17 (2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-020-00172-5.

- Isolation and identification of mosquito larvicidal compound from Abutilon indicum (Linn.) Sweet. Parasitol. Res.. 2008;102:981-988.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ovicidal and oviposition deterrent activities of medicinal plant extracts against Aedes aegypti L. and Culex quinquefasciatus Say mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) Osong. Public. Health. Res. Perspect.. 2015;6:64-69.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review of the efficacy of rectal paraldehyde in the management of acute and prolonged tonic–clonic convulsions. Arch. Dis.. 2009;94:720-723.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and antibacterial activity of gold nanoparticles. Int. J. Infect. Control.. 2021;14:1842-1847.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using vallarai chooranam and their potential biomedical applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater.. 2020;30:4709-4719.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular characterization of a proteolytic bacterium in Panchagavya: an organic fertilizer mixture. J. Ayurveda. Integr. Med.. 2018;9:123-125.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Panchagavya–an ecofriendly insecticide and organic growth promoter of plants. Int. J. Adv. Res.. 2014;2:22-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of cow dung based herbal mosquito repellent. J. Krishi. Vigyan.. 2017;6:50-53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plumeria pudica Jacq. flower extract - mediated silver nanoparticles: characterization and evaluation of biomedical applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun.. 2021;126:108470.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity of synthesized silver nanoparticles from Curcuma zedoaria essential oil against Culex quinquefasciatus. Insects. 2019;10:27.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of active ingredients and larvicidal activity of clove and cinnamon essential oils against Anopheles gambiae (sensu lato) Parasit. Vectors. 2017;10:411.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquito larvicidal properties of essential oil of an indigenous plant, Ipomoea cairica Linn. JPN. J. infect. Dis.. 2004;57:176-177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of some weed extracts for ovicidal and larvicidal activities against dengue vector Aedes aegypti. J. Basic. Appl. Zool.. 2021;82:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Viremia and clinical presentation in Nicaraguan patients infected with Zika virus, chikungunya virus, and dengue virus. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2016;63:1584-2159.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alternative insecticides: an urgent need. Trends. parasitol.. 2002;18:161-163.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]