Translate this page into:

Bioaccumulation Factor (BAF) of heavy metals in green seaweed to assess the phytoremediation potential

⁎Corresponding authors. shahidmahboob60@hotmail.com (Shahid Mahboobb), abhijit_mitra@hotmail.com (Abhijit Mitra)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Heavy metals are mostly discharged from several anthropogenic sources in the lower Gangetic delta. They are a matter of great concern due to their non-conservative nature. Heavy metals Zn, Cu, and Pb, were analyzed in the estuarine water and thallus body tissue of Enteromorpha compressa from 10 different stations in the lower Gangetic delta complex through three seasons. The levels of heavy metals varied as per the order Zn > Cu > Pb in both the aquatic phase and biological sample, irrespective of stations. The maximum concentration of Zn was observed in Kakdwip (Stn. IV) and both Cu and Pb in Nayachar Island (Stn. III). The minimum was observed in Bagmara (Stn. X) for all metals in the seaweed sample through all the seasons. The levels of all dissolved heavy metals were maximum in Nayachar Island (Stn. III) and lowest in Bagmara (Stn. IV). A distinct seasonal pattern is observed for all the selected metals with the highest value during monsoon, followed by postmonsoon and premonsoon. The Bioaccumulation Factors (BAF) computed for all the selected heavy metals exhibit the highest value for Pb, followed by Zn and Cu. The highest BAF observed for Pb is an issue of grave concern due to its toxic nature compared to Zn and Cu. ANOVA computed on the data sets of dissolved and bioaccumulated heavy metals and BAFs exhibit significant Spatio-temporal variation, suggesting the need for seasonal and station-wise monitoring, preferably in context to the BAF. The spatial variation in the level of heavy metals in the seaweed species Enteromorpha compressa is due to differences in activities and sources of pollution in these regions. The overall result suggests that seaweed may be a potential bio-purifier in the coastal area mainly exposed to many anthropogenic activities.

Keywords

Enteromorpha compressa

Heavy metals

BAF

Phytoremediation

Anthropogenic

1 Introduction

Heavy metals are discharged in the lower Gangetic delta by a wide range of anthropogenic activities and pose a severe threat to the ecosystem (Mitra, 2019). These metals are persistent, bioaccumulative, transferred to the next trophic level, and interfere in biological processes, causing toxicity (Unlu and Gumgum, 1993; Censi et al., 2006). Although Cu and Zn are components of many oxidative enzymes and occur naturally in the environment, increased levels of Cu and Zn can cause acute or chronic toxicity to aquatic plants and animals. Several anthropogenic activities such as electroplating, mining, textile factory effluents, pesticides, paint, and pigment industries are responsible for the rising concentration of Cu in the environment. Zn is released from various industries like refineries, brass manufacture, metal plating, and plumbing (Alluri et al., 2007). Pb occurs naturally in the environment in small concentrations. However, manufacturing and mining activities and the burning of fossil fuels increase the concentration and lead to acute or chronic toxicity (Seiler et al., 1994; Deng et al., 2006). The heavy metals (Hg, As, Pb, Ni, Cd, Cu, Zn) cause toxicity by entering the biological system (Misra and Gedamu, 1989; Pan et al., 1994; Garty, 2001; Bañuelos et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2015). They displace the original metals required for various enzymatic functions from their protein binding sites, causing enzymatic disruption and cell distortion (Jaishankar et al., 2014). Oxidative stress is also caused by heavy metals (Mudipalli, 2008), leading to cellular damage and, eventually, death of the cell (Das et al., 2008; Krystofova et al., 2009; Sánchez-Chardi et al., 2009). The two critical factors, duration of exposure and concentration, are essential in the manifestation toxicity (Marschner, 1995).

Phytoremediation is an eco-friendly and cost-effective technique to remove pollutants from soil, water, and sediments (Negri et al., 1996; Vyslouzilova et al., 2003; Cho-Ruk et al., 2006). The lower Gangetic delta located at the apex of the Bay of Bengal is stressed due to anthropogenic pressure. The ability of seaweeds to bioaccumulate and absorb heavy metals makes it a suitable biomarker of heavy metal pollution (Rybak et al., 2012; Gresswell et al., 2014; van Ginneken and de Vries, 2018; Yozukmaz et al., 2018; Anbalagan and Sivakami, 2018; Asiandu and Wahyudi, 2021; Danouche et al., 2021; Foday Jr et al., 2021; Rakib et al., 2021; Znad et al., 2022). The biosorption of heavy metals in seaweeds occurs in two stages. In the first phase, absorption occurs on the surface and then accumulation in the cell in the next stage (Monteiro et al., 2011). Seaweeds are benthic macroalgae inhabiting the marine and brackish water. They are non-flowering plants and thallophytic in nature. Their thallus body is different from plants in vegetative parts, consisting of the holdfast, stipe, and blade instead of root, stem, and leaf. Seaweeds are attached to hard substrata like boulders, rocks, and even on the pneumatophores of the mangrove species. In Indian Sundarbans and surroundings, seaweeds are widely available in the intertidal zone. Based on the presence of pigments, seaweeds are categorized into three groups, namely Chlorophyceae (green seaweed), Phaeophyceae (brown seaweed), and Rhodophyceae (red seaweed). Among the dominant seaweed species in Indian Sundarbans, Enteromorpha compressa (green seaweed) is one of them. It belongs to the Ulvaceae family and is abundantly found in almost all the islands of Sundarbans (Mitra, 2013; Mitra and Zaman, 2015; Mitra and Zaman, 2016; Mitra, 2020).

Since seaweeds are benthic, they accumulate heavy metals from the ambient environment and act as excellent agents of biofiltration. Their absorption ability depends on the availability of the toxic substances from the ambient aquatic sub-system and the sediments, which is expressed as BAF. It is an index of the degree of accumulation of a pollutant or contaminant in an organism relative to its ambient environment. The study was undertaken to analyze the concentrations of selected heavy metals (Cu, Pb, and Zn) in the thallus body of E. compressa and ambient aquatic media collected from 10 different stations in the lower Gangetic delta complex through three seasons in 2019. The metals were selected based on their abundance in the present geographical locale, as pointed out by earlier workers (Mitra et al., 2011; Barua et al., 2011; Mitra and Banerjee, 2011; Mitra et al., 2012a; Mitra et al., 2012b; Ray Chaudhuri et al., 2014; Zaman et al., 2014; Das et al., 2015; Ghosh et al., 2016a,b; Mitra, 2019; Mitra and Zaman, 2021). The stations were selected to get a comparative spatial picture of bioaccumulation as Stn. I (Canning), Stn. III (Nayachar Island), Stn. IV (Kakdwip), Stn. VI (Sagar South), and Stn. VIII (Frasergunge) is exposed to highly high anthropogenic stress than Stn. II (Gosaba), Stn. V (Chemaguri), Stn. VII (Jambu Island), Stn. IX (Bali Island), and Stn. X (Bagmara) is located in the mangrove belt and can be considered a control site. The BAF has been used to determine the potential of seaweed to act as a bio-purifier in the coastal regions heavily impacted by human intervention.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study site

The Gangetic Delta (21°30′N to 24°40′N latitude and 88°00′E to 91°50′E longitude) is located at the apex of the Bay of Bengal and covers an area of 60,500 sq. km in the state of West Bengal, India, and Bangladesh. It is the dwelling place of more than 60 million people, and many towns and cities (Calcutta now Kolkata, Nadia, Jessore, Khulna, etc.) have flourished here. One of the World's most extensive mangrove forests, the Sundarbans, is situated in the southern coastal part of the delta.

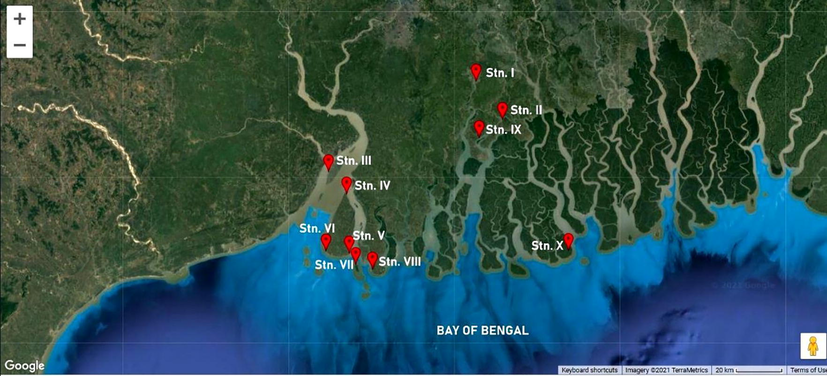

Ten different stations were selected from Indian Sundarbans on the northeast coast of the Bay of Bengal to collect seaweed E. compressa samples. The ten stations in the study were Canning (Stn. I), Gosaba (Stn. II), Nayachar Island (Stn. III), Kakdwip (Stn. IV), Chemaguri (Stn. V), Sagar South (Stn. VI), Jambu Island (Stn. VII), Frasergunge (Stn. VIII), Bali Island (Stn. IX) and Bagmara (Stn, X) (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Stations

Coordinates

Canning (Stn. I)

22⁰19′03.20″N; 88⁰41′04.43″E

Gosaba (Stn. II)

22⁰09′59.20″N; 88⁰47′52.00″E

Nayachar Island (Stn. III)

21⁰57′38.89″N; 88⁰03′28.48″E

Kakdwip (Stn. IV)

21⁰52′26.50″N; 88⁰08′04.48″E

Chemaguri (Stn. V)

22⁰38′27.50″N; 88⁰08′47.92″E

Sagar South (Stn. VI)

21⁰39′02.11″N; 88⁰02′47.31″E

Jambu Island (Stn. VII)

21⁰35′42.03″N; 88⁰10′22.76″E

Frasergunge (Stn. VIII)

21⁰34′39.84″N; 88⁰14′44.32″E

Bali Island (Stn. IX)

22⁰05′46.11″N; 88⁰41′49.57″E

Bagmara (Stn. X)

21⁰39′04.45″N; 89⁰04′40.59″E

Map showing study sites in the lower Gangetic Delta. Source: Google Map (Software used by Mapmaker).

2.2 Sampling and heavy metals analysis in ambient media

The analysis of dissolved heavy metals was done with water samples collected through three seasons during high tide conditions from all the selected ten stations. The collected water samples were filtered through a 0.45 µm Millipore membrane and stored in clean TARSON bottles until analysis. The water samples from each station were preconcentrated using APDC-MIBK extraction procedure as per the standard method (Apha, 1989). The resulting solution was aspirated to the Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, Model 3030) fitted with an HGA-500 graphite furnace atomizer. The data were expressed in ppm units. The process of preparing the analytical blank was similar, and analyses were done in triplicate. The accuracy of the dissolved heavy metal determinations was indicated by the excellent agreement between our values with certified reference seawater material values (CASS 2) (Table 2).

Element

Certified value (µg l−1)

Laboratory results (µg l−1)

Zn

1.97 ± 0.12

2.01 ± 0.14

Cu

0.675 ± 0.039

0.786 ± 0.058

Pb

0.019 ± 0.006

0.029 ± 0.009

2.3 Sampling of seaweed and heavy metals analysis in body tissue

Enteromorpha compressa species were collected from each station during premonsoon, monsoon, and postmonsoon in 2019 and washed with distilled water. Each 10 mg of the washed seaweed sample was taken in a petri-dish, then these samples were heated overnight in a hot-air oven at 60⁰C. 1 gm of the dried sample was digested using a mixture of hydrogen peroxide and nitric acid, followed by hydrochloric acid (Kumar et al., 2012). Pb, Cu, and Zn were analyzed through Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, Model 3030) fitted with an HGA-500 graphite furnace atomizer using a blank.

2.4 Assessment of BAF

BAF is a ratio of the concentration of heavy metal in tissue to the concentration of heavy metal in ambient aquatic media, and it is determined using the formula given below: where Contissue = concentration of heavy metals in tissue, Contissue = concentration of heavy metals in water.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the variation of selected heavy metals between seasons and stations using SPSS 16.0. P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

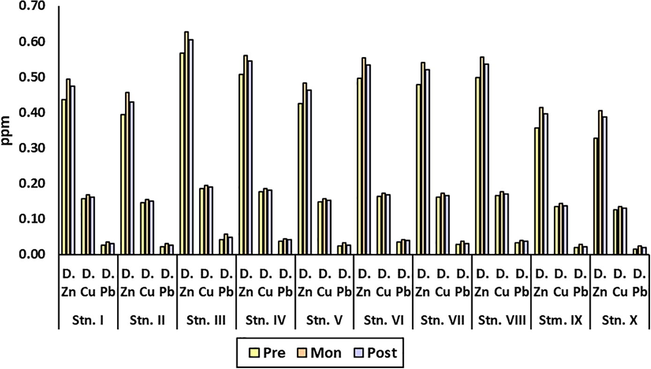

3.1 Dissolved heavy metals

The concentration of dissolved heavy metals during the three seasons is highlighted in Fig. 2. The concentration of heavy metals was Zn > Cu > Pb, and seasonal variation was monsoon > postmonsoon > premonsoon. The highest concentrations of all the three selected dissolved heavy metals (Zn, Cu, Pb) were found at Nayachar Island and the lowest at Bagmara. The concentration of dissolved Zn and Cu followed the order Nayachar Island > Kakdwip > Frasergunge > Sagar South > Jambu Island > Canning > Chemaguri > Gosaba > Bali Island > Bagmara. However, the concentration of dissolved Pb followed the order Nayachar Island > Kakdwip > Sagar South > Frasergunge > Jambu Island > Canning > Chemaguri > Gosaba > Bali Island > Baghmara.

The concentration of dissolved heavy metals (in ppm) during three seasons at study sites.

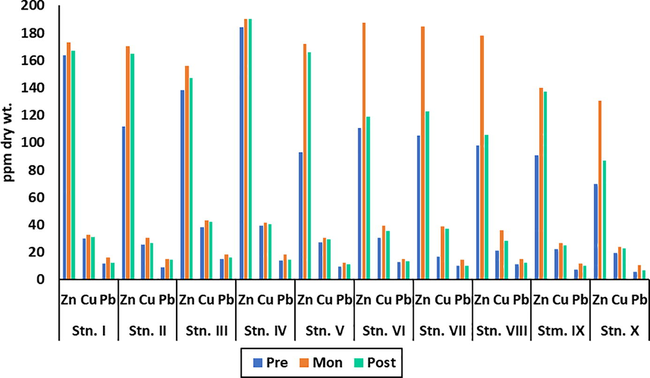

3.2 Accumulated heavy metals in body tissue

The concentrations of accumulated heavy metals Zn, Cu, and Pb in the thallus body of E. compressa during three seasons are highlighted in Fig. 3. The order of accumulated heavy metals was Zn > Cu > Pb, and the seasonal variation pattern was monsoon > postmonsoon > premonsoon, which is similar to the trend of dissolved heavy metals. The study showed that the maximum concentration of Cu and Pb in the body tissue was at Nayachar Island, whereas the minimum was at Bagmara. In the case of Zn, the maximum concentration was at Kakdwip and the minimum at Bagmara. The order for Zn in the body tissue was Kakdwip > Canning > Gosaba > Nayachar Island > Chemaguri > Sagar South > Jambu Island > Frasergunge > Bali Island > Bagmara. The trend for Cu in the body tissue was Nayachar Island > Kakdwip > Sagar South > Canning > Jambu Island > Chemaguri > Frasergunge > Gosaba > Bali Island > Bagmara, whereas for Pb the order was Nayachar Island > Kakdwip > Sagar South > Canning > Gosaba > Frasergunge > Jambu Island > Chemaguri > Bali Island > Bagmara.

Concentration of heavy metals in E. compressa (in ppm) during three seasons at study sites.

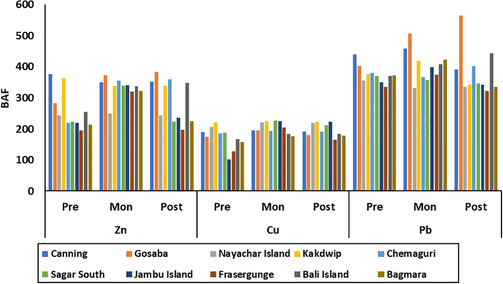

3.3 BAF

The BAF value for each metal through three seasons in all the stations is shown in Fig. 4. The highest value was observed in the BAF for Pb, followed by Zn and Cu. The BAF for Zn follows the order Canning > Gosaba > Kakdwip > Bali Island > Chemaguri > Jambu Island > Sagar South > Bagmara > Nayachar Island > Frasergunge whereas the order for Cu is Kakdwip > Nayachar Island > Sagar South > Canning > Chemaguri > Jambu Island > Gosaba > Bali Island > Bagmara > Frasergunge. The order of BAF for Pb is Gosaba > Canning > Bali Island > Chemaguri > Kakdwip > Bagmara > Jambu Island > Sagar South > Frasergunge > Nayachar Island.

BAF values for all selected heavy metals in all the study sites during three seasons.

3.4 Analysis of variance (ANOVA)

ANOVA results of dissolved and accumulated heavy metals reveal significant variation between stations and seasons (Table 3). ANOVA of BAF of Zn varies significantly between stations and seasons, but in Cu and Pb, no significant variation was observed between stations and seasons, respectively.

Parameters

Variables

Fobs

Fcrit

Thallus body

Zn

Between Stations

4.5432

2.4563

Between Seasons

16.6895

3.5546

Cu

Between Stations

8.8329

2.4563

Between Seasons

10.2224

3.5546

Pb

Between Stations

24.8926

2.4563

Between Seasons

50.8025

3.5546

Ambient water

Zn

Between Stations

897.4160

2.4563

Between Seasons

549.9245

3.5546

Cu

Between Stations

9566.2642

2.4563

Between Seasons

2216.8024

3.5546

Pb

Between Stations

160.5752

2.4563

Between Seasons

128.0734

3.5546

BAF

Zn

Between Stations

3.5924

2.4563

Between Seasons

7.4790

3.5546

Cu

Between Stations

2.3334

2.4563

Between Seasons

6.2074

3.5546

Pb

Between Stations

4.3821

2.4563

Between Seasons

1.6350

3.5546

4 Discussion

The aquatic environment has become more contaminated due to massive urbanization and industrialization, and the present geographical locale has no exception to this usual trend. The intense technological development and urbanization of the cities like Howrah, Kolkata, and the upcoming port-cum-industrial complex (Haldia complex) in West Bengal are responsible for the substantial imbalance in the area's ecology. The Lower Gangetic delta region is anthropogenically stressed because of tourism units, fish landing stations, downstream industries, etc. Approximately 9000 trawlers and fishing vessels ply in this region for fishing activities. These trawlers and fishing vessels frequently use antifouling paints to keep away the settlements of biofoulers on their body surface, which are the sources of zinc, copper, lead, etc. (Fig. 5) (Mitra, 1998; Mitra et al., 2000; Das et al., 2005; Mitra et al., 2013; Mitra, 2013; Mitra and Zaman, 2015, Mitra and Zaman, 2016; Mitra and Zaman, 2020).

Use of antifouling paints on the fishing vessels and trawlers.

The metals released from these point sources either precipitate on the sediment bed or remain dissolved from where they get transferred to the body tissues of the organisms. The process of transference/bioaccumulation is a function of several environmental variables like salinity, pH, and water temperature (Mitra, 2013). The bioaccumulation of heavy metals also exhibited significant seasonal variations with the highest values during monsoon, followed by postmonsoon and premonsoon (Fig. 4). It may be attributed to marked seasonal variations of dissolved heavy metals (Fig. 2), exhibiting the trend monsoon > postmonsoon > premonsoon. The highest value during monsoon may be attributed to two factors viz i) maximum run-off during monsoon and ii) lowering of pH due to increased dilution that favors the dissolution process from the sediment bed to the water column (Mitra, 2013, 2020). The significant positive correlations between dissolved and bioaccumulated heavy metals (Zn dissolved × Zn tissue = 0.5201, p < 0.05; Cu dissolved × Cu tissue = 0.5317, p < 0.05; Pb dissolved × Pb tissue = 0.6108, p < 0.05). It supports the view of the accumulation of heavy metals by E. compressa from ambient water. This is probably the cause for the highest accumulation and considerably high BAF in monsoon compared to the other two seasons. The impact of seasons on the bioaccumulation pattern of heavy metals in organisms has also been documented by earlier workers in the present geographical locale (Mitra et al., 2011, 2012a; Mitra, 2013, 2020). It is well documented that mangrove and mangrove associate floral species can bioaccumulate heavy metals in their body tissues (Kraus et al., 1986; Kraus, 1988; Niyogi et al., 1997; MacFarlane, 2002; Banerjee et al., 2014; Chakraborty et al., 2014a,b; Nayak et al., 2016).

Very few researchers have depicted the BAF of heavy metals in the body tissues of the aquatic vegetation, which may act as a proxy for the translocation of these heavy metals from the aquatic phase to the plant body. The higher the value of the BAF, the greater the potential of plant species to absorb the heavy metals from the surrounding aquatic phase. In the present study, the BAF is highest in the case of Pb, which implies that the species E. compressa has the potential to purify the surrounding water from Pb. In the study area, Pb originates from the antifouling paints used for conditioning fishing vessels and trawlers, printing industries, and battery manufacturing units. Most industries are concentrated in the downstream region of the lower Gangetic Delta, in and around the Haldia port-cum industrial complex.

ANOVA with our data sets on dissolved and bioaccumulated heavy metals and BAF exhibited significant spatial-seasonal differences (except Cu and Pb), as shown in Table 3. These variations of the stations in terms of contamination subsequent bioaccumulation of the selected heavy metals by E. compressa. The variation in bioaccumulation pattern was attributed to a different degree of anthropogenic stress around the selected sites. Stn. 1 (Canning), Stn. III (Nayachar Island), Stn. IV (Kakdwip), Stn. VI (Sagar South) and Stn. VIII (Frasergunge) has high anthropogenic stress due to fish landing stations, industrial units, shrimp culture farms, and tourism units, whereas Stn. II (Gosaba), Stn. V (Chemaguri), Stn. VII (Jambu Island), Stn. IX (Bali Island) and Stn. X (Bagmara) is located in mangrove dominated region, which is relatively free of anthropogenic activities except for occasional tourism.

Many more industries are in the pipeline, which implies that the contamination of coastal zones due to heavy metals will soon increase if there is no proper treatment plant. A Combined Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP) is suggested for the region to minimize the rate of toxic waste discharge.

All agricultural waste, industrial waste, municipal, nuclear and domestic waste are ultimately deposited into the aquatic system. The need of the hour is to remove the heavy metal toxicants by using fast-growing plants for phytoremediation. This eco-friendly approach is a much-preferred alternative to chemical plants (Pilon-Smits, 2005). The high value of BAF for heavy metals, preferably Pb, confirms E. compressa as potential floral species for biopurification. Seaweed culture by traditional rope culture method (Fig. 6) can be a viable road map to reducing heavy metal pollution locally.

Traditional rope culture of seaweed.

However, a limitation exists in this domain related to pH of the aquatic phase or the seaweed-based biopurification system. A low pH is to be maintained (compared to the average estuarine pH of 8.30) to transfer the heavy metals in the thallus body of E. compressa. So, phytoremediation can be achieved by diluting the biotreatment plant with harvested rainwater.

5 Conclusion

We can conclude from the values of the BAF so obtained that the macroalgal species E. compressa needs to be cultured through traditional rope culture in the vicinity of the industrial discharge points. It might be an eco-friendly approach to cost-effectively purify contaminated water.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2022R436) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Biosorption: An eco-friendly alternative for heavy metal removal. Afr. J Biotechnol.. 2007;6(25):2924-2931.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in water and algae of Mukkombu in the River Cauvery System, Tiruchirappalli District, Tamil Nadu, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci.. 2018;7(1):1067-1072.

- [Google Scholar]

- Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, Part 3, Determination of Metals (17th,). Washington DC: American Public Health Association; 1989. p. :164.

- Phycoremediation: heavy metals green-removal by microalgae and its application in biofuel production. J. Environ. Treat. Tech.. 2021;9(3):647-656.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bioaccumulation pattern of heavy metals in saltmarsh grass (Porteresia coarctata) of Indian Sundarbans. J. Energy Environ. Carbon Credits. (STM). 2014;4(3):1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selenium biofortifcation of broccoli and carrots grown in soil amended with Se-enriched hyperaccumulator Stanleya pinnata. Food Chem.. 2015;166:603-608.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seasonal variation of heavy metals accumulation in water and oyster (Saccostrea cucullata) inhabiting central and western sector of Indian Sundarbans. Environ. Res. J.. 2011;5(3):121-130.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metals in coastal water systems. A case study from the northwestern Gulf of Thailand. Chemosphere. 2006;64(7):1167-1176.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avicennia alba: an indicator of heavy metal pollution in Indian Sundarban estuaries. J. Environ. Sci. Comput. Sci. Eng.. 2014;3(4):1796-1807.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioaccumulation pattern of heavy metals in three mangrove species of Avicennia inhabiting lower Gangetic delta. J. Chem. Biol. Phys.. 2014;4(4):3884-3896.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perennial plants in the phytoremediation of lead-contaminated soils. Biotechnology. 2006;5(1):1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phycoremediation mechanisms of heavy metals using living green microalgae: physicochemical and molecular approaches for enhancing selectivity and removal capacity. Heliyon. 2021;7(7)

- [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, its adverse health effects and oxidative stress. Indian J. Med. Res.. 2008;128:412-425.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metal pollution in marine and estuarine environment: The case of North and South 24 Parganas district of coastal west Bengal, Indian. J Environ. Ecoplan.. 2005;10(1):19-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conservative pollutants in Ganges shark: A case study from the lower Gangetic delta region of Indian sub-continent. J. Chem. Biol. Phys. Sci.. 2015;5(2):2122-2132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lead and zinc accumulation and tolerance in populations of six wetland plants. Environ. Pollut.. 2006;141(1):69-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of toxic heavy metals from contaminated aqueous solutions using seaweeds: A review. Sustainability. 2021;13:12311.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biomonitoring atmospheric heavy metals with lichens: Theory and application. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant. Sci.. 2001;20:309-371.

- [Google Scholar]

- First record on seasonal variation of Heavy metal concentrations in Neritina (Dostia) Violacea (Gmelin) from Nayachar Island, West Bengal, India. J. Environ. Sci. Comp. Sci. Eng. Technol.. 2016;5(2):23-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, I., Mitra, A., Rudra, T., Pramanick, P., Biswas, P.P., 2016A. Bioaccumulation pattern of heavy metals by gastropods: A case study from lower Gangetic delta. J. Environ. Sci. Comp. Sci. Eng. Technol. 5 (1), 99-102.

- Bioaccumulation and retention kinetics of cadmium in the freshwater decapod Macrobrachium australiense. Aquat. Toxicol.. 2014;148:174-183.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol.. 2014;7:60-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accumulation and excretion of five heavy metals by the saltmarsh cordgrass Spartina alterniflora. Butt. New. Jersey. Aca. Sci.. 1988;33:39-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- The excretion of heavy metals by the salt marsh cord grass, Spartina alterniflora, and Spartina’s role in mercury cycling. Mar. Environ. Res.. 1986;20(4):307-316.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sunflower plants as bioindicators of environmental pollution with lead (II) ions. Sensors. 2009;9:5040-5058.

- [Google Scholar]

- AAS estimation of heavy metals and trace elements in indian herbal cosmetic preparations. Res. J. Chem. Sci.. 2012;2(3):46-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leaf biochemical parameters in Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh as potential biomarkers of heavy metal stress in estuarine ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Butt.. 2002;44(3):244-256.

- [Google Scholar]

- Marschner, H., 1995. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (2nd Edition). Published by Elsevier, eBook ISBN: 9780080571874, Paperback ISBN: 9780124735439, 889.

- Heavy metal tolerant transgenic Brassica napus L. and Nicotiana tabacum L. plants. Theor. Appl. Genet.. 1989;78(2):161-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of coastal pollution in West Bengal with special reference to heavy metals. J. India. Ocean. Stud.. 1998;5(2):135-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, A., 2013. Sensitivity of Mangrove Ecosystem to Changing Climate. Publisher Springer New Delhi Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London, ISBN-10: 8132215087; ISBN-13: 978-8132215080.

- Mitra, A., 2019. Estuarine Pollution in the Lower Gangetic Delta, published by Springer International Publishing, ISBN 978-3-319-93305-4, XVI:371. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93305-4.

- Mitra, A., 2020. Mangrove Forests in India, published by Springer, eBook ISBN 978-3-030-20595-9, Hardcover ISBN 978-3-030-20594-2, XV, 361. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20595-9.

- Trace elements in edible shellfish species from the lower Gangetic delta. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. (ELSEVIER). 2011;74:1512-1517.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shrimp tissue quality in the lower Gangetic delta at the apex of Bay of Bengal. Toxicol. Environ. Chem.. 2011;93(3):565-574.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of trace metals in commercially important crustaceans collected from UNESCO protected World Heritage Site of Indian Sundarbans. Turkish J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.. 2012;12:53-66.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metal concentration in Indian coastal fishes. Res. J. Chem. Environ.. 2000;4(4):35-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concentrations of some heavy metals in commercially important finfish and shellfish of the River Ganga. Environ. Monit. Assess.. 2012;184:2219-2230.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, A., Zaman, S., 2015. Blue carbon reservoir of the blue planet published by Springer, ISBN 978-81-322-2106-7, XII, pp. 299. DOI: 10.1007/978-81-322-2107-4.

- Mitra, A., Zaman, S., 2016. Basics of Marine and Estuarine Ecology. Published by Springer, ISBN 978-81-322-2705-2, XII, pp. 483. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2707-6.

- Mitra, A., Zaman, S., 2020. Environmental Science - A Ground Zero Observation on the Indian Subcontinent. Published by Springer International Publishing, eBook ISBN 978-3-030-49131-4, Hardcover ISBN 978-3-030-49130-7, XIV, 478.

- Mitra, A., Zaman, S., 2021. Estuarine Acidification: Exploring the Situation of Mangrove Dominated Indian Sundarban Estuaries. Springer, Chem, e-Book ISBN 978-3-030-84792-0, XII, pp. 402, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84792-0.

- Mitra, A., Zaman, S., Bhattacharyya, S.B., 2013. Heavy metal pollution in the lower Gangetic ecosystem. In: Water Insecurity: A Social Dilemma (Ed. Md. Anwarul Abedin, Umma Habiba and Rajib Shaw). Published by Emerald Group Publishing Limited, ISBN: 978-1-78190-882-2.

- Toxicity of cadmium and zinc on two microalgae, Scenedesmus obliquus and Desmodesmus pleiomorphus, from Northern Portugal. J. Appl. Phycol.. 2011;23(1):97-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metals (micro nutrients or toxicants) and global health. Indian J. Med. Res.. 2008;128:331-334.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioaccumulation of Heavy metals in sand binder Ipomoea pes-caprae: A case study from lower Gangetic delta region. Int. J. Trend. Res. Dev.. 2016;3(2):358-361.

- [Google Scholar]

- Negri, M.C., Hinchman, R.R., Gatliff, E.G. 1996. Phytoremediation: using green plants to clean up contaminate soil, groundwater, and wastewater (No. ANL/ES/CP-89941; CONF-960804-38). Argonne National Lab., IL (United States).

- Niyogi, S., Mitra, A., Aich, A., Choudhury, A., 1997. Sonneratia apetala – an indicator of heavy metal pollution in the coastal zone of West Bengal (India). In: Advances in Environmental Science (Ed. C.S.P. Iyer) Educational Publishers and Distributors. 283-287.

- Expression of mouse metallothionein-I gene confers cadmium resistance in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant. Mol. Biol.. 1994;24(2):341-351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Macroalgae in biomonitoring of metal pollution in the Bay of Bengal coastal waters of Cox’s Bazar and surrounding areas. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11:20999.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of acidification on heavy metals in Hooghly Estuary. J. Harmonized Res. Appl. Sci.. 2014;2(2):91-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Freshwater Ulva (Chlorophyta) as a bioaccumulator of selected heavy metals (Cd, Ni and Pb) and alkaline earth metals (Ca and Mg) Chemosphere. 2012;89(9):1066-1076.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metals in liver and kidneys and the effects of chronic exposure to pyrite mine pollution in the shrew Crocidura russula inhabiting the protected wetland of Doñana. Chemosphere. 2009;76:387-394.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seiler, H., Sigel, A., Sigel, H. (Eds.). 1994. Handbook on metals in clinical and analytical chemistry. CRC Press, ISBN 9780824790943, 940.

- Preparation, characterization, and ion exchange behavior of nanocomposite polyaniline zirconium (IV) selenotungstophosphate for the separation of toxic metal ions. Ionics. 2015;21(4):1045-1055.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concentrations of Cu and Zn in Fish and sediments from the Tigris River in Turkey. Chemosphere. 1993;26:2055-2206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seaweeds as Biomonitoring System for Heavy Metal (HM) Accumulation and Contamination of Our Oceans. Am. J. Plant Sci.. 2018;9:1514-1530.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- As, Cd, Pb and Zn uptake by Salix spp. clones grown in soil enrich by high load of these elements. Plant Soil. Environ.. 2003;49(5):191-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metal bioaccumulation in Enteromorpha intestinalis, (L.) Nees, a macrophytic algae: the example of Kadin Creek (Western Anatolia) Environ. Sci. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol.. 2018;61:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Forecasting heavy metal level on the basis of acidification trend in the major estuarine system of Indian Sundarbans. J Energy. Environ Carbon Credit.. 2014;4(2):1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The utilization of algae and seaweed biomass for bioremediation of heavy metal contaminated wastewater. Molecules. 2022;27:1275.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]