Translate this page into:

Berberine ameliorates intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) rats

⁎Corresponding author. wyzhen211@126.com (Yuzhen Wang) zkx66165@sina.com (Yuzhen Wang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objective

To study the protective role of berberine (BBR) against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) on intestinal barrier via investigating its effect on intestinal permeability and intestinal innate immune system in a rat model.

Method

Sprague-Dawley rats were randomly divided into three groups: control rats (group N), high-fat diet (HFD) model rats (group M) and BBR-treated rats (group B). Rats in group M and group B were fed with HFD for 12 weeks to induce NAFLD. Rats in group B were then received 4 weeks of BBR administration with continuous HFD feeding. Samples were collected at 16th week.

Results

HFD feeding increased the body weight of rats and caused liver steatosis as indicated by hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining. Analysis of serum parameters showed that alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), endotoxin, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-18 (IL-18), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were significantly higher in group M as compared group N. These results confirmed the successful establishment of NAFLD in rats. With 4 weeks of BBR administration, body weight of group B decreased significantly as compared with group M. Serum levels of ALT, AST, TC, TG, endotoxin, IL-1β, IL-18 and TNF-α reduced significantly and hepatocyte steatosis ameliorated. RT-PCR and Western blot analysis showed that BBR reduced the elevated mRNA and protein expressions of innate immune response elements NOD1, NOD2 and NLRP3 that were caused by HFD. BBR also antagonized the effect of NAFLD on Caspase-1 and Claudin-4 protein expressions.

Conclusions

BBR alleviates endotoxemia, reduces serum lipids, increases liver function, reduces systemic inflammation and diminishes liver inflammation and steatosis in NAFLD rats. The protective effect of BBR against NALFD is achieved through ameliorating intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction partly by improving permeability of intestinal mucosa and modulating intestinal innate immune components.

Keywords

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Berberine

Intestinal mucosal barrier

1 Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one of the most common chronic liver diseases worldwide. Pathogenesis of NAFLD has not been fully elucidated. The ‘gut-liver axis’ has become a hot topic in the field of liver disease. Of which, intestinal mucosal barrier damage has gained attention from researchers. It is believed that bacterial flora imbalance, increased intestinal mucosal permeability, bacterial translocation and intestinal endotoxemia play important roles in pathogenesis of NAFLD (Dai and Wang, 2015; Federico et al., 2016; Pang et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2017). This theory provides an in-depth explanation on relationship between intestine and liver during pathological state. When intestinal mucosal barrier is damaged, toxic substances such as bacteria and toxins in intestine enter liver via portal vein system. Immune system such as Kupffer cell (KC) in liver is then activated by these harmful substances, and a series of inflammatory factors which may lead to liver damage are released. Thus, maintaining intestinal mucosal barrier integrity might be crucial for the development of NAFLD.

Innate immune system of the epithelial mucosal barrier recognizes pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) via pattern recognition receptors (PRRS) and subsequently induces immune response. Innate immune system consists of several pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) and Rig-1-like receptors (RLRs) (Jin et al., 2017). When intestinal epithelial cell encounters invasive pathogen or pathogen in close contact with cell membrane, PAMP is transferred to cytoplasm and interacts with specialized NLRs, NOD1 and NOD2, which in turn triggers defense response. NOD1 and NOD2 interact with nucleotide-binding oligomeric domain protein (RIP2) and further activate NF-κB, MAPK and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), which induce release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Caruso et al., 2014). Combination of NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC) induces activation of caspase-1 and generation of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 (Yang et al., 2019). Activation of NOD1 and NOD2 induces pro-inflammatory antibacterial response and subsequent immune response.

Berberine (BBR) is an isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from Coptis chinensis. It has strong anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. Studies have shown that berberine can reduce intestinal mucosal damage caused by chronic stress and reduce expression of inflammatory mediators during severe abdominal infection or sepsis, and thereby ameliorate intestinal mucosa barrier damage and reduce permeability of intestinal wall (Tan et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019). BBR has been reported to alleviate hepatic steatosis and prevents the pathological progression of liver (Chang et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2008). We have previously linked the protective effect of BBR against NAFLD to the improvement of the intestinal barrier function via the modulating the gut microbiota (Li et al., 2017). In the present study, we further study the protective role of BBR on NAFLD on the intestinal barrier function by investigating its effect on intestinal permeability and intestinal innate immune system.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animals and experimental design

All experimental procedures were performed with approval of the Animal Ethics Committee of Hebei General Hospital. Thirty-three male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats, weighing 200 ± 10 g, were purchased from Animal Experimental Center of Hebei Medical University (certificate number: 1606071). The rats were housed in the animal laboratory of Hebei Provincial People's Hospital at controlled temperature 18 °C–26 °C, 40%–70% humidity under a 12-h light/dark cycle. The rats were given free access to food and water.

The animals were randomly divided into 3 groups: normal control group (N group), high-fat diet model group (M group) and berberine group (B group). Group N was given normal feed whereas group M and group B were fed with high-fat diet (HFD). Ordinary feed contained 348 kcal of energy per 100 g with a fat content of 10.3% whereas high-fat feed contained 501 kcal of energy per 100 g with a fat content of 59.8%. One animal in each group was sacrificed at 12th week to examine the degree of fat deposition in hepatocytes by H&E staining to confirm the establishment of NAFLD. Group B was intragastrically administered with 150 mg/kg/day BBR (Northeast General pharmaceutical Factory, China) starting from 12th week, while group N and group M received the same amount of physiological saline solution in the same manner for Group B. After 4 weeks of continuous gavage, rats were fasted for overnight. Blood samples were obtained via abdominal aorta before the animals were sacrificed. Liver and small intestine were collected for further analysis.

2.2 Analysis of serum parameters

Blood was collected from abdominal aorta, centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 15 min, and supernatant was transferred into pyrogen-free microcentrifuge tube. Serum levels of ALT and AST were examined using kits purchased from Changchun Huili Biotech (China) whereas TC and TG were detected using kits from Biosina (China) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Serum endotoxin level was determined by limulus amebocyte lysate reagent method (Zhanjiang Andus Biological, China). IL-1β and TNF-α were measured with ELISA kits purchased from China 4A Biotechnology whereas IL-18 ELISA kit was obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (China).

2.3 Collection of ileum terminal intestinal tissue

Ileum terminal tissue was quickly removed and cut into segments. A segment of 0.5 cm length for each sample was snapped frozen immediately. The tissues were then subjected to Western blotting and qRT-PCR analysis.

2.4 Liver histopathology

Liver tissue blocks were fixed, dehydrated, embedded and sectioned. Representative tissue sections were performed for H&E staining and examined under a light microscope.

2.5 Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

RNA from small intestine tissue was isolated using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, USA). The isolated RNAs were reverse transcribed using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Quantification of cDNA was performed using DreamTaq Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer instructions. The data were normalized to β-actin mRNA expression. Primer sequences used are listed in Table 1.

Genes

Primer sequences

Length

NOD1

Forward: TATCGGAGCCAGGTATGT

Reverse: CGCCCTCACTTGTTATTC92 bp

NOD2

Forward: ACTTCCATTCCATCCCG

Reverse: CCCAATGTCCAAGCGAC143 bp

NLRP3

Forward: CCTCAACAGACGCTACACC

Reverse: CACATCTTAGTCCTGCCAAT99 bp

β-Actin

Forward: CCTAGACTTCGAGCAAGAGA

Reverse: GGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGA140 bp

2.6 Western immunoblot analysis

Small intestine tissue was lysed with RIPA buffer (Sigma, USA) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors and the cell pellets were removed by centrifugation (12,000g) for 10 min at 4 °C. Equal amount of proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes immunoblotted with antibodies against NOD1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), NOD2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), Glyceraldeyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Abcom, UK), Caspase-1 (Abcam, USA), NLRP3 (Bioss, China) and Claudin 4 (Bioss, China). Proteins were visualized and detected by chemiluminescence image system (Bio-Rad).

2.7 Statistical analysis

All data was processed using SPSS 21.0 software. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA and SNK tests were used for comparison between groups. All data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance, and P < 0.05 indicated statistically significance.

3 Results

3.1 Body weight changes in rats

HFD-fed rat tended to develop obesity. As expected, body weight of rats fed with HFD (group M and B) after 12 weeks of feeding was significantly higher as compared to group N (P < 0.05). The body weight of group M continued to increase with another 4 weeks of HFD feeding (P < 0.05, group M versus group N). In group B, we observed a significant decrease in body weight in rats after 4 weeks of BBR administration as compared to group M (P < 0.05) (Table 1), indicating that BBR reduces weight gain by HFD.

3.2 Blood indicator results in rats

3.2.1 Serum biochemical indicators

Significant increases in serum TC and TG levels were observed in group M as compared control group while remarkably decreases were observed for group B (p < 0.05, group M versus group B) (Table 3). The results are consistent with previous studies indicating that BBR involves in lipid regulation (Chang et al., 2010; Li et al., 2017). Elevated serum levels of ALT and AST by HFD indicating an obvious liver injury in rats of group M (p < 0.05) (Table 3). BBR treatment for 4 weeks significantly decrease the serum level of ALT and AST (P < 0.05, group M versus group B), suggesting that BBR administration relieves HFD induced liver injury.

3.2.2 Levels of endotoxin, IL-1β, IL-18 and TNF-α

NAFLD is associated with increased serum endotoxin level (Harte et al., 2010). Table 2 showed that endotoxin level was increased in group M (P < 0.05, group M versus group N) and significantly reduced in group B (P < 0.05, group B versus group M). BBR could also reduce the levels of several inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18 which were upregulated in NAFLD rats (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Group

12th week (g)

16th week (g)

N

387.2 ± 10.1

425.2 ± 16.3

M

471.8 ± 12.9*

524.8 ± 13.3*

B

470.6 ± 15.3*

492.8 ± 11.1#,*

Group

N

M

B

ALT (U/L)

44.16 ± 3.64

82.56 ± 3.83*

62.85 ± 3.30#,*

AST (U/L)

117.46 ± 5.62

203.57 ± 6.61*

162.52 ± 6.40#,*

TC (U/L)

1.139 ± 0.023

1.781 ± 0.038*

1.537 ± 0.044#,*

TG (U/L)

0.488 ± 0.055

1.086 ± 0.032*

0.799 ± 0.033#,*

Endotoxin (EU/ml)

0.160 ± 0.005

0.373 ± 0.008*

0.268 ± 0.006#,*

IL-1β (ng/L)

51.41 ± 4.16

103.38 ± 5.89*

78.85 ± 7.21#,*

IL-18 (pg/ml)

134.76 ± 9.64

273.71 ± 12.39*

197.91 ± 14.96#,*

TNF-α (pg/ml)

86.81 ± 7.32

201.24 ± 14.14*

132.94 ± 17.06#,*

3.3 H&E staining of liver tissue

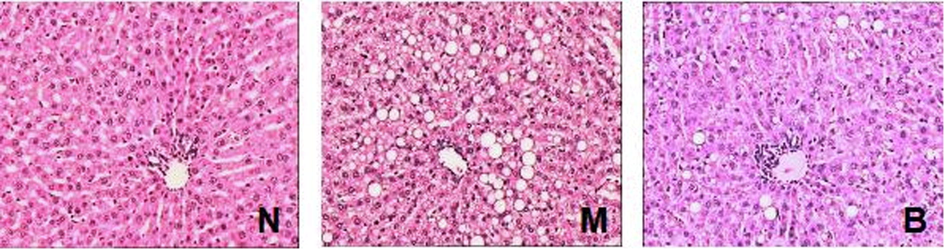

Successful establishment of NAFLD rat model was confirmed at 12th week by H&E staining (data not sown). After 16 weeks of HFD feeding, hepatic lobule structure of rats in group M was disordered. Hepatocytes became swollen and were not aligned regularly. In addition, hepatocytes of group M were filled with fat vacuoles of different sizes, and nuclei was pushed to one side by the lipid as compared to group N (Fig. 1). With 4 weeks treatment of BBR, the hepatocyte swelling was reduced, fat vacuoles were diminished, and liver cells arrangement was more regular as compared with group M (Fig. 1), indicating that BBR ameliorates liver steatosis in NAFLD rats.

Representative H&E-stained sections of liver tissues of groups N, M and B with 200× magnification. Group N, rats with no treatment; group M, HFD-fed NAFLD model rats; group B, HFD-fed rats treated with berberine; HFD, high-fat diet.

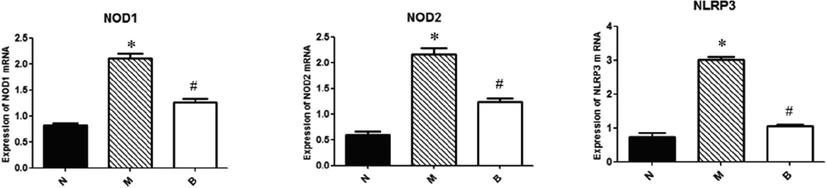

3.4 mRNA expressions of NOD1, NOD2 and NLRP3 in ileum tissues

RT-PCR analysis showed that the expression of pattern recognition receptors NOD1, NOD2 and NLRP3 was increased in the small intestine of group M as compared to group N (Fig. 2). BBR significantly reduced the elevated mRNA levels of pattern recognition receptors (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2), suggesting that BBR regulates immune response elements in the intestine.

RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of NOD1, NOD2 and NLRP3 in small intestine. Bar graphs are shown as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with group N, #P < 0.05 compared with group M.

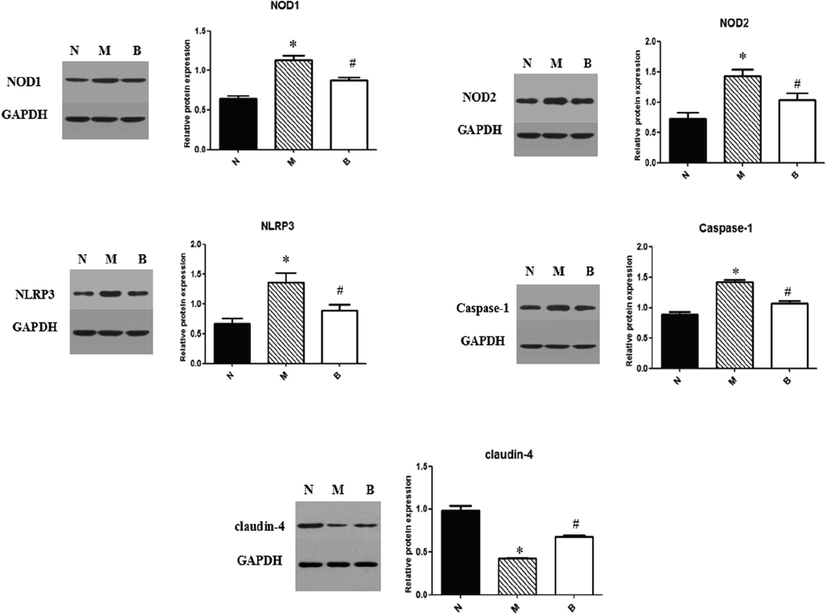

3.5 Protein expression of NOD1, NOD2, NLRP3, caspase-1 and claudin-4 in ileum tissues

Consistent with the RT-PCR analysis, western blot results showed that expressions of NOD1, NOD2, NLRP3 were upregulated in NAFLD intestine and reduced by BBR treatment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Examination of caspase-1 protein expression revealed that caspase-1 was increased in group M (P < 0.05, group M versus group N) and BBR reduced its expression (P < 0.05, group B versus group M). Claudin-4, a key molecule of tight junction which act to regulate epithelial permeability, was downregulated in NAFLD rats (P < 0.05, group M versus group N). The elevated claudin-4 expression can be attenuated by BBR (P < 0.05, group B versus group M).

Immuno-blots and protein expressions quantification of NOD1, NOD2, NLRP3, caspase-1 and claudin-4 in small intestine. Bar graphs are shown as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with group N, #P < 0.05 compared with group M.

4 Discussion

Various methods have been developed to produce animal models of NAFLD. HFD feeding is the most common method which pathogenesis and pathological changes are more similar to human NAFLD. Based on the experimental conditions reported in the previous studies, we modified the conditions and successfully induced NAFLD in male SD through HFD with a fat content 59.8%. Weight of rats fed with HFD was significantly higher than that of control rats and the fatty vacuoles were observed in the liver tissues. These indicate that HFD, obesity and NAFLD are closely related. Our histological analyses showed that alleviations of liver steatosis and ameliorate pathological progression of liver in BBR-treated rats. In addition, reduced lipids level, improved liver function and inhibition of systemic inflammation were observed. Taken together, the results reveal that BBR effectively ameliorates NAFLD progression. These observations were in line with the previous reports (Chang et al., 2010; Li et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2008).

NAFLD is associated with the increased permeability of intestinal mucosa, which is proposed to play a role in liver steatosis (Miele et al., 2009). Tight junction (TJ) is the primary intercellular junction that play crucial role in regulating intestinal permeability. Claudin, one of the major members of TJ, contains a charged amino acid in one of the extracellular loops that determines selection of transepithelial resistance and extracellular charge between cells. Regulation of claudin-4 is critical for tight junction function as it has been shown that formation of tight junction was severely interrupted when mutation occurred on the phosphorylation site of claudin-4 (Aono and Hirai, 2008). Our study demonstrated that the expression of claudin-4 protein was decreased in the ileum tissue of NAFLD rats, indicating that barrier function of intestinal mucosa was impaired. When the rats were administrated with BBR, expression of claudin-4 protein was partially restored. At the same time, the circulation endotoxin level was reduced by BBR. Our results suggest that BBR acts on the intestinal mechanical barrier of NAFLD by reducing the permeability of the intestinal wall and alleviate endotoxemia via regulating tight junction. We have previously reported that BBR can increase expression of occludin which is one of the key components of tight junction in intestinal epithelial cells (Li et al., 2017). It is possible that BBR concurrently modulate both occludin and claudin to ameliorate intestinal barrier dysfunction.

Gastrointestinal mucosal epithelial barrier is supported by maintenance of intestinal flora dynamic balance and regulation of antimicrobial substance release. Host recognizes endogenous or exogenous microorganisms through intestinal NLRs under normal physiological conditions. After ligand binding, NOD1/NOD2 and RIP2 activate NF-κB and MAPK pathways which result in the expression of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Caruso et al., 2014). Studies have reported that NLRs and symbiotic bacteria can interact with each other (Claes et al., 2015; Philpott et al., 2014). NOD2 mainly recognizes muramyldipeptide (MDP) peptidoglycan fragments produced by intestinal symbiotic or pathogenic bacteria. NOD2 can limit pathological growth of common bacteroides in intestine and thus suppress inflammation of small intestine (Ramanan et al., 2014). It has been also found that relationship between intestinal commensal bacteria can be established through immune system and recognition process of NOD1-dependent ligands (Bouskra et al., 2008). By regulating the composition of the gut microbiota, and the immune response against the intestinal bacteria, NLRs act as intestinal barrier guardians. HFD could cause an altered gut microbiota composition. Studies have investigated the effect of BBR on intestinal microbiota in HFD-induced obesity and NAFLD rats (Li et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2015). They found that BBR can modulate of intestinal microbiota thereby preserving intestinal barrier functions, providing protection against the diseases. Our findings on NOD1, NOD2, NLRP3 and caspase-1 provide supporting evidence on how BBR improve intestinal microenvironment. Restoration of the expression and response of classic NLRs and their downstream cascades (e.g. caspase-1) by BBR could possibly modulate the intestinal microbiota structure, protect against bacterial translocation, maintain the gut homeostasis thereby attenuating disruption of gut barrier in NAFLD.

Endotoxin is a complex lipopolysaccharide (LPS) found on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria that can form gut-derived endotoxemia when it enters blood through intestinal mucosa (Federico et al., 2016). LPS can enter liver via portal vein and directly damage liver cells. LPS can also activate hepatic stellate cells and Kupffer cells and induce release of a large number of inflammatory mediators which cause liver inflammation and fibrosis (Trikudanathan and Vege, 2014), thus promoting the development of NAFLD. In our study, we showed that circulating endotoxin level is increased in NAFLD rats, implicating that NAFLD is closely related to endotoxemia and intestinal mucosal barrier is damaged. With BBR treatment, the elevated endotoxin level was reduced, suggesting that BBR can alleviate endotoxemia in NAFLD through reducing intestinal permeability.

In summary, intestinal mucosal mechanical barrier is impaired in HFD-induced NAFLD rats and lead to increased intestinal permeability. BBR can restore the function of intestinal mucosal mechanical barrier via improving the permeability of intestinal mucosa thereby alleviating endotoxemia and reducing lipid deposition in liver of NAFLD. This study further elaborated the theory of gut-liver circulation and provided a theoretical basis for treatment of NAFLD with BBR.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Phosphorylation of claudin-4 is required for tight junction formation in a human keratinocyte cell line. Exp. Cell Res.. 2008;314:3326-3339.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature. 2008;456:507-510.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- NOD1 and NOD2: signaling, host defense, and inflammatory disease. Immunity. 2014;41:898-908.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Berberine reduces methylation of the MTTP promoter and alleviates fatty liver induced by a high-fat diet in rats. J. Lipid Res.. 2010;51:2504-2515.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- NOD-like receptors: guardians of intestinal mucosal barriers. Physiology (Bethesda). 2015;30:241-250.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Role of gut barrier function in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract.. 2015;2015:287348

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Targeting gut-liver axis for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: translational and clinical evidence. Transl. Res.. 2016;167:116-124.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Elevated endotoxin levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Inflamm. (Lond.). 2010;7:15.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mitochondrial control of innate immunity and inflammation. Immune Netw.. 2017;17:77-88.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Amelioration of intestinal barrier dysfunction by berberine in the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. Pharmacogn. Mag.. 2017;13:677-682.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:1877-1887.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Significant positive association of endotoxemia with histological severity in 237 patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.. 2017;46:175-182.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- NOD proteins: regulators of inflammation in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol.. 2014;14:9-23.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial sensor Nod2 prevents inflammation of the small intestine by restricting the expansion of the commensal Bacteroides vulgatus. Immunity. 2014;41:311-324.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial characteristics of Berberine against prosthetic joint infection-related Staphylococcus aureus of different multi-locus sequence types. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.. 2019;19:218.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Current concepts of the role of abdominal compartment syndrome in acute pancreatitis – an opportunity or merely an epiphenomenon. Pancreatology. 2014;14:238-243.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Berberine protects against diet-induced obesity through regulating metabolic endotoxemia and gut hormone levels. Mol. Med. Rep.. 2017;15:2765-2787.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Probiotics may delay the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by restoring the gut microbiota structure and improving intestinal endotoxemia. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7:45176.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic regulation of inflammasomes in inflammation. Immunology. 2019;157:95-109.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modulation of gut microbiota by berberine and metformin during the treatment of high-fat diet-induced obesity in rats. Sci. Rep.. 2015;5:14405.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic effects of berberine on blood, liver glucolipid metabolism and liver PPARs expression in diabetic hyperlipidemic rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull.. 2008;31:1169-1176.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of berberine hydrochloride on DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol.. 2019;68:242-251.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]