Translate this page into:

Azadirachta indica based biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and evaluation of their antibacterial and cytotoxic effects

⁎Corresponding authors. kj.bmmrc@gmail.com (Kaiser Jamil), kmujeeb@ksu.edu.sa (Mujeeb Khan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Due to the growing threat to the environment by the climate change, the development of sustainable and environmental friendly methods for the preparation of metallic nanoparticles (NPs) is highly desirable. Herein, we demonstrate a simple and eco-friendly method for the preparation of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and aqueous solution of silver nitrate (AgNO3). The effect of concentration of leaf extract and temperature on the synthesis of AgNPs is studied. It was revealed that 1 mM of AgNO3, leaf extract concentration of 60 mg/mL, 30 min of reaction time and a temperature 85 °C were found to be optimum for the synthesis good quality AgNPs. The formation of AgNPs was confirmed by UV–Vis analysis, where the UV spectrum exhibited a highest absorption peak at ∼410 nm corresponding to the surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) of the AgNPs. Furthermore, the antibacterial activity of biosynthesised AgNPs was investigated and the inhibitory concentrations of 0.5 µg/mL for Escherichia coli and 1.0 µg/mL for Staphylococcus aureus were found. Besides, the in vitro cytotoxicity investigation of biosynthesized AgNPs against human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells via MTT assay showed that the minimum inhibitory concentration of 15.6 µg/mL was required. Therefore, the eco-friendly and cost effective synthesis of AgNPs has potential for biomedical applications and this method can be used for the large scale production of AgNPs.

Keywords

Azadirachta indica

AgNPs

Biosynthesis

Antimicrobial activities

Cytotoxicity

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology has developed as the most attracting field of multidisciplinary science (Arvizo et al., 2012). By virtue of their small size, nanoparticles (NPs) possess excellent physical and chemical properties (Sau et al., 2010). These properties have been successfully utilized in several technological and biomedical fields (Doane and Burda, 2012). So far, tremendous efforts have been diverted towards the fabrication of nanoparticles based novel materials, such as biomedical devices, implants and surgical instruments with improved functional properties and explore their applications in various fields including bio-sensing, bio-imaging and healthcare sector (Pereira et al., 2015). Therefore, designing the novel, benign and eco-friendly protocol for the synthesis of NPs with custom made structural properties is highly desirable.

Typically, NPs have been synthesized using various physical and chemical methods based on the suitability of the protocols to achieve the required applications (Rao et al., 2012). The physical methods such as, ball milling, electric arc discharge, flame pyrolysis and laser ablation etc., usually involves expensive instruments, high temperature and pressure (Ladj et al., 2013). Whereas, using the chemical methods NPs are prepared by the reduction/decomposition of metal complexes in solutions using various chemical reductants, such as sodium borohydride, hydrazine or at elevated temperature (Betke and Kickelbick, 2014). Although, these methods have been extensively applied but the reactants, reductants, stabilizers and various organic solvents used in these methods are toxic and potentially hazardous for the environment. Currently, green chemistry is an emerging phenomenon for the synthesis of various chemical products, including NPs, which greatly reduces the threat to the environment by eliminating the hazardous materials from the preparations methods that are toxic to human health. Therefore, green synthesis of metal nanoparticles provides a better platform for the synthesis of various nanomaterials, including silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) (Nabikhan et al., 2010). For the synthesis and stabilization of AgNPs various methods have been applied so far, such as, chemical synthesis (Hu et al., 2009), physical (Jung et al., 2006) and biological methods (Velavan et al., 2012). In contrast to chemical and physical methods, biological methods have attracted significant attention for the synthesis of AgNPs, which are more economical and environmental friendly. In this regard, numerous studies have been reported for the synthesis of AgNPs using various biological materials such as bacteria (Deshmukh et al., 2012), algae (Xie et al., 2007), fungi (Ingle et al., 2008) and plants and so on (Gardea-Torresdey et al., 2003; Shankar et al., 2003).

Among various biomaterials, plant extracts have gained decent attention due to their eco-friendly nature, cost effectiveness, and easy availability. Moreover, the synthesized nanoparticles remained stable under various conditions (Tran and Le, 2013). Several studies have been reported on the synthesis of AgNPs using the extracts of different parts of the plants. For instance, in a recent study, the leaf broth of Arbutus unedo, was used as both reducing and stabilizing agent to prepare spherical AgNPs, where the size of Ag NPs were between 3 and 20 nm (Kouvaris et al., 2012). In another study, the root extract of Erythrina indica was used to prepare spherical AgNPs with size in the range of 20–118 nm (Sre et al., 2015). FTIR analysis revealed that various polyphenols including, terpenes, phenol, flavonols and tannin were responsible for preparation and stabilization of AgNPs.

In the present study, we have investigated the biosynthesis of AgNPs using Azadirachta indica (neem) leaf extract, which belongs to family Meliaceae and is abundant in the Indian subcontinent. It has been widely used in traditional medicine due to its antibacterial, anthelmintic, antifungal and skin healing properties. Although, in earlier studies, different parts of A. indica have been used for the preparation of AgNPs (Ahmed et al., 2016; Nazeruddin et al., 2014; Roy et al., 2017). For instance, Tripathy et al., have applied leaves of A. indica for the preparation of AgNPs and also investigated the effect of different parameters, such as amount of reductant and reactants, pH of the reaction mixture, mixing ratio of the reactants and the time of reaction on the morphology and size of as-prepared AgNPs (Tripathy et al., 2010). However, due to various intrinsic and extrinsic factors such as genetic variations, ecological and environmental factors, plants typically demonstrate high chemical diversity (Srivastava et al., 2005; Vokou et al., 1993). Particularly, the type of soil, temperature of the region, radiation and photoperiod play a critical role in defining the quality and quantity of the phytochemical constituents (Kokkini et al., 1994). Due to this the amount and variety of reductants present in different parts of the plants used for the preparation of metallic NPs may vary significantly. Therefore, the comparative investigation of the ability of the extracts of same plant belonging to different origin for the synthesis of same nanoparticles is highly desirable.

Besides, it is has been widely reported that AgNPs synthesized from plant extracts commonly possess potent antibacterial activity against a variety of bacteria including E. coli, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa (Rai et al., 2009). The activity of the AgNPs depends on the size, shape and stabilizing property of nanoparticles (Morones et al., 2005). In various reports it was demonstrated that capping agents are used for the stabilization of nanoparticles, and the capped AgNPs give better results for the antibacterial activity, as compared to uncapped AgNPs (Amato et al., 2011; Jaiswal et al., 2010). In the present study, we have investigated the antibacterial activity of AgNPs against various gram positive and gram negative bacteria some of which are human pathogens.

In addition, regardless of the various applications and toxic effects of AgNPs in medical fields, comparatively very few in vitro studies have shown the cytotoxic effect of AgNPs on different cell lines such as HELA (Sukirtha et al., 2012), MCF-7 (Franco-Molina et al., 2010) and NIH3T (Hsin et al., 2008). Some studies have reported the use of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and cancer cells isolated from patients as model systems for evaluating cytotoxicity of AgNPs (Jeong et al., 2014). A report shows that various plant materials such as fruit, flower, Leaves and bark of plants show cytotoxic effect on human whole blood due to presence of tannins, flavonoids, phenols and proteins (Sivarajan and Balachandran, 1994). However, there were few studies on the antibacterial activities of biosynthesized AgNPs using leaf extract of neem plant (Shankar et al., 2004; Tripathi et al., 2009). Therefore, in this study, for the first time, we have developed a protocol for biosynthesis of AgNPs from A. indica and evaluated their effects on primary cancer cells isolated from the patients suffering from acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

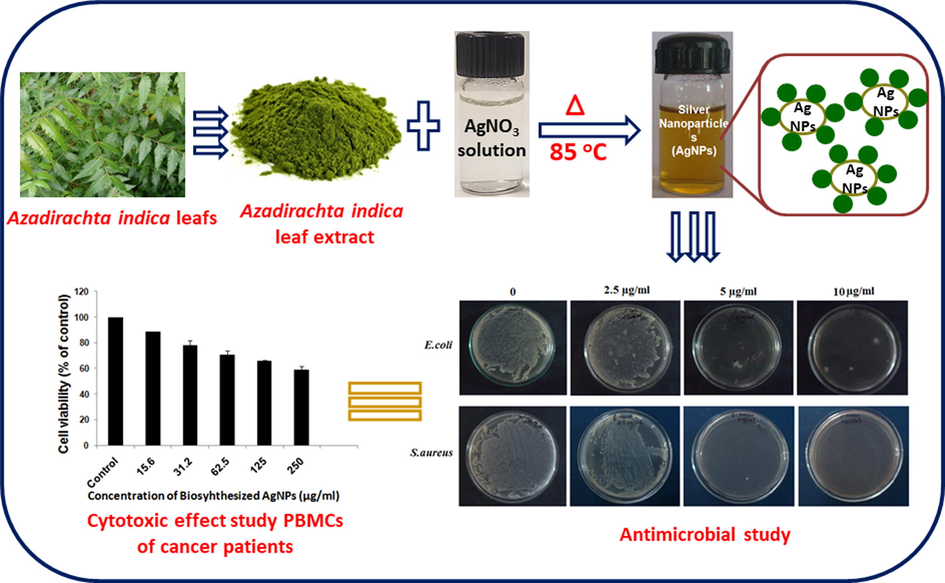

Herein, we demonstrate the effectiveness of A. indica leaf extract towards the synthesis of AgNPs (Scheme 1) and also studied the effect of various parameters such as temperature and concentration of leaf extracts on the quality of resultant AgNPs. The resultant AgNPs were identified by various spectroscopic and microscopic techniques. In addition, the as-prepared AgNPs were also tested against gram positive and gram negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus for their antimicrobial activities. Besides, the anticancer properties of as-prepared AgNPs have also been evaluated.

Schematic representation of UV–Visible spectrum of biosynthesis of AgNPs using A. indica leaves extract and AgNO3.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

All chemicals used were HPLC grade, silver nitrate (AgNO3), and Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) was purchased from Hi-Media Laboratories, Mumbai, India. Tissue culture plastic wares were obtained from Tarsons Products Pvt. Ltd., India. Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin and MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) were purchased from Hi-Media Laboratories, Mumbai, India. All solutions were prepared in sterile Milli-Q water.

2.2 Collection and preparation of plant material

Fresh leaves of A. indica were collected around the JNIAS campus, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. The leaves were washed twice with tap water and thrice with distilled water. The leaves were then air dried in the incubator at 37 °C for three days and ground into powder using an electric blender. The leaves extract was prepared by mixing 20 gm of leaf powder with 300 mL of Milli-Q water (i.e. 66.66 mg/mL) in a 500 mL conical flask. The mixture was stirred and heated between 90 °C and 100 °C for 30 min using a hot plate with magnetic stirrer. After cooling the solution was subjected to centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 15 min and the supernatant was filtered with WhatmanNo.1 filter paper. The pH of the extract was 7.3 to 7.4. The extract was stored at 4 °C for further use. Here onwards A. indica leaf extract will be referred to as leaves extract.

2.3 Synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)

For reduction of silver ions, required amount of leaves extract was added to 90 mL of 1 mM silver nitrate (AgNO3). The mixture was heated for at 100 °C for desired time with continuous stirring till the color of the solution changed from light green to yellow (Parashar et al., 2009).

2.4 Optimization of silver nanoparticles synthesis

In order to optimize the formation of AgNPs, some of the main parameters were investigated including incubation time; temperature; AgNO3 concentration and leaves extract concentration. We standardized the effect of incubation time on AgNPs formation by mixing the 1 mL (66.66 mg/mL) of leaves extract with 1 mM AgNO3 solution and incubated at a temperature of 85 °C for different interval of time (0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min). To investigate the effect of temperature on the formation of AgNPs, we used 1 mM of AgNO3 solution to which 1 mL of leaves extract was added and this mixture was then exposed to different temperatures (25 °C, 35 °C, 45 °C, 55 °C, 65 °C, 75 °C and 85 °C). To elucidate the effects of AgNO3 solution, various experiment were carried out by mixing different amount of AgNO3 (0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.0 and 2.0 mM), while the amount of leaves extract was kept constant (1 mL). In order to optimize the leaves extract for the formation of AgNPs, 1 mM AgNO3 was mixed with different concentrations of leaves extract (0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 mL (6.66 mg/mL)) and the mixtures were subjected to UV–VIS spectroscopy analysis, to determine optimal production of AgNPs.

2.5 Characterization of AgNPs

The biosynthesized AgNPs were characterised by UV–visible spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The bioreduction of Ag+ ions in solutions was monitored by measuring the 3 mL of mixture containing the leaves extract and AgNO3 solution. Formation of AgNPs in solution was monitored via UV–Vis spectrophotometer (LIUV-310, Lambda Scientific, Australia). The association of biomolecules with synthesised AgNPs was examined by using FTIR spectroscope, the Spectrum One (Perkin Elmer, USA) with Kbr pellets. The FTIR spectra of washed and purified AgNPs powder were recorded over the range of 400–4000 cm−1 and the resolution was kept as 4 cm−1. The crystalline nature of synthesized AgNPs was analysed on a XRD-6000 X-ray diffractometer model (Shimadzu, Japan) with 40 kV, 30 mA with Cu k a radiation at 2θ angle. The morphology of the synthesised AgNPs was examined by SEM using SU1510 electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan). The size and morphology of biosynthesized AgNPs were analyzed using TEM (Philips model CM 200). The samples for TEM were prepared by placing a drop of primary sample on a copper grid, which was then dried for 6 h at 80 °C in an oven.

2.6 Antibacterial test

The synthesized AgNPs from leaves extract were used for evaluating antibacterial test. Two different microbial cultures were obtained from MTCC, IMTECH Chandigarh in lyophilized form. The bacterial strains used were E. coli (MTCC, No. 1722) and S. aureus (MTCC, No. 96). The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) assay is defined as the lowest concentration of a particular anti-microbial agent that can inhibit the growth of bacteria after overnight incubation. MIC was determined according to the standard protocol used for Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI M07-AB) (Ansari et al., 2011; Lara et al., 2010). To standardize the turbidity of bacterial inoculums the McFarland standard was used. The bacterial culture was grown in Mueller Hilton broth and the optical density was adjusted up to turbidity equivalent to barium sulphate 0.5 McFarland standards using the UV–Vis spectrophotometer of 600 nm (LIUV-310, Lambda Scientific, Australia). 10 μl of diluted cell suspension was inoculated to 90 μl of Mueller-Hilton broth with a desired concentration (Control as without AgNPs, and 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 µg/mL AgNPs) in each 96-well plate. Mueller-Hinton broth without any nanoparticles was used for control wells. The culture plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Bacterial growth was determined by monitoring the 96 well plates in a micro plate reader (Lambda Scientific Pty Ltd, Australia) at 600 nm. All the experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.7 Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

The Minimum Bactericidal Concentration was defined as the lowest concentration that enabled no growth on the agar (99.9% kill). The Minimum Bactericidal Concentration method was used to measure the antibacterial properties of the biosynthesized AgNPs against bacterial strains: E. coli and S. aureus. Subsequently, 100 µl of fresh culture of each test organism was spread on Mueller–Hinton agar plates and different concentration of biosynthesized AgNPs (0, 2.5 µg/mL, 5 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL and Control without AgNPs) suspension was added on plates containing Mueller–Hinton agar and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., USA).

2.8 Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

To determine the toxic effect of biosynthesized AgNPs against cancer cells, the fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients by venipuncture. The samples were collected in anticoagulant EDTA containing tube (BD Vacutainer® Blood Collection tubes, USA). Acute lymphoblastic leukemia blood samples were diluted with phosphate buffer saline at 1:1 ratio as described by Fuss et al (Fuss et al., 2004), with a few modifications. Diluted blood samples were carefully overlaid onto HiSepTM LSM medium (Hi-Media Laboratories, Mumbai, India) and centrifuged at 400×g (5430R, Eppendorf, Germany) for 30 min at 20 °C. After centrifugation the buffy coat containing PBMC was carefully removed and placed into a fresh falcon tube containing PBS and re-centrifuged at 260×g for 10 min. This step is repeated twice to remove any traces of unwanted materials, such as platelets. After centrifugation, the pure PBMC were stained with trypan blue and counted in a haemocytometer for cell viability. The cells were then resuspended at 1 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100g/mL streptomycin (Hi-Media, India).

2.9 In vitro cytotoxicity assay

In vitro cytotoxicity assay were performed according to the method described by Denizot and Lang (Denizot and Lang, 1986) using the principle of reduction of 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2) -2, 5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) to formazan by the dehydrogenase enzymes present in mitochondria. PBMCs cells were cultured and seeded into 96-well plates approximately 1 × 103 cells per well and cells were treated with different concentrations of biosynthesized AgNPs. The serial dilutions of AgNPs were prepared in RPMI medium in the range of (15.6, 31.2, 62.5, 125, 250 μg/mL). Treated cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h hours for cell viability assay. After 24 h the treated cells were subjected to MTT assay. The MTT stock of 5 mg/mL was prepared in PBS. The PBMCs were treated with 10 μl of MTT solution, added to each well. The plates were incubated for 2–3 h at 37 °C for reduction of MTT by metabolically viable cells. The action of dehydrogenase enzyme results in the formation of purple color formazan crystals. The crystals were then solubilized by adding 10 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The formed crystal’s optical density was observed at 570 nm in a multi well ELISA plate reader (Lambda Scientific Pty Ltd, Australia). The optical density data were expressed as cell viability percentage.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV–Vis) analysis

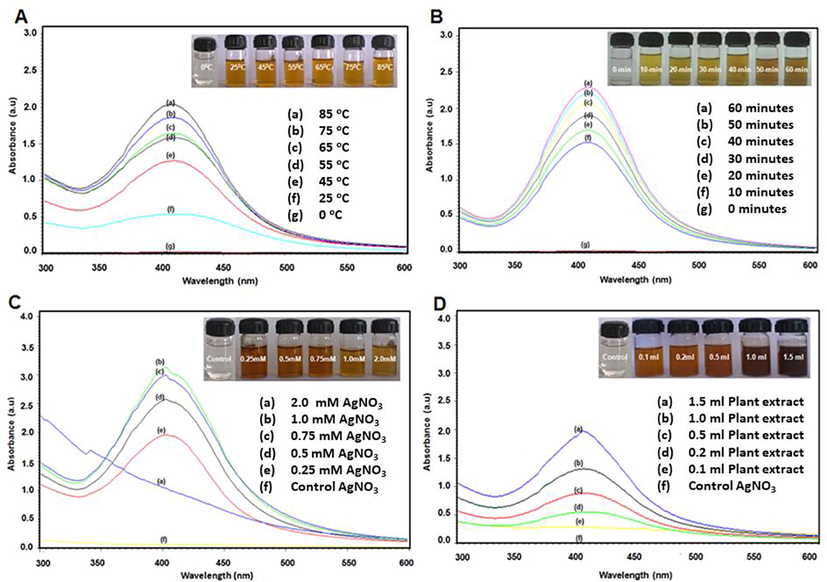

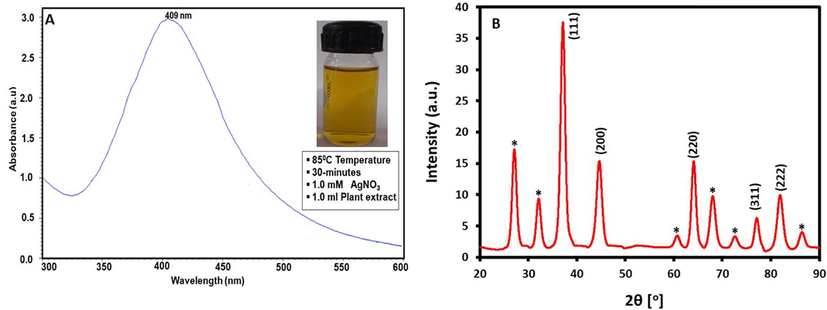

Initially, UV analysis was applied to quickly confirm the formation and stability of AgNPs, since the plasmon peak of Ag is sensitive to the size and shape of the resultant NPs. To begin with, the UV spectrum of biosynthesized AgNPs was measured (cf. Fig. 1). AgNPs were prepared by using 1 mL of leaves extract and 1 mM of AgNO3 for 30 min at 85 °C. Typically a broad peaks at higher wavelengths suggest an increase in particle size, while a narrow peak at a shorter wavelength indicate the formation of smaller size AgNPs (Khan et al., 2013). In this case, a sharp and relatively narrow absorption was observed at 409 nm, which indicate towards the formation of good quality AgNPs (Nazeruddin et al., 2014). Next, the effect of temperature on the synthesis of AgNPs was evaluated. For this purpose, the bio-reduction of Ag+ ions in solution was monitored at different temperatures, e.g., 25 °C, 35 °C, 45 °C, 55 °C, 65 °C, 75 °C and 85 °C, while keeping the concentration of reactant and reductant constant. Fig. 1a, shows the effect of temperature on the synthesis of nanoparticles. Initially at room temperature (25 °C), the reaction mixture containing 1 mM of AgNO3 and 1 mL of leaves extract upon stirring for 30 min, produced a broad absorption peak with an absorption maximum at 413 nm. However, upon increasing the temperature, the intensity of this peak increases significantly and peak became sharper and slightly shifted to lower wavelength. This clearly indicates, higher temperatures are required for the nucleation process to occur smoothly and to produce high-quality AgNPs. While at room temperature, the process of nucleation slow down significantly and produce less amount of AgNPs which is clearly reflected by the lower intensity of the SPR band. It has been reported that the quality of AgNPs is reflected by the intensity and position of SPR peak of AgNPs, which typically occur between 380 and 450 nm. While the sharp and lower wavelength absorption peak reflect the smaller size of AgNPs, whereas a broader peak at higher wavelength points towards the presence of larger size and aggregated AgNPs (Smitha et al., 2008). In this case, when the temperature is increased from 25 °C to 85 °C, the SPR peaks became sharper and shifted to lower wavelength. For instance, upon increasing the temperature between 25 °C and 65 °C, the position of peak is shifted from 413 to 410 nm, while upon further increasing the temperature up to 85 °C, the peak has appeared at 409 nm (cf. Fig. 2 A). Notably, in case of AgNPs prepared at room temperature from A. indica leaves collected from New Delhi region, the absorption peak occurred at ∼445 nm. The shift of absorption peak to the higher wavelength suggested the formation of larger size and irregular shape AgNPs which is rather confirmed by TEM analysis (Ahmed et al., 2016). This clearly suggests that the A. indica leaves collected from Hyderabad region have produced relatively high-quality AgNPs with smaller size in less amount of time at lower and higher temperatures.

UV–Visible absorption spectra of biosynthesized AgNPs using A. indica leaves extract. Effects of (A) time (10 to 60-minutes at 85 °C) (B) Temperature (20 °C to 85 °C for 30-minutes) (C) AgNO3 concentration (0.25 mM to 2 mM) and (D) different leaves extract concentration (0.1 mL to 1.5 mL) on the synthesis of AgNPs.

(A)The UV–Visible absorption spectrum of biosynthesized AgNPs using A. indica leaves extract. The absorption spectra of AgNPs exhibited a strong peak at 409 nm upon incubation for 85 °C for 30-minutes with 1 mM AgNO3 and 1 mL leaves extract and (B) X-ray diffraction (XRD) diffractogram of biosynthesized AgNPs using A. indica leaves extract.

Thereafter, the effect of time on the process of reduction of Ag ions was analyzed. For this purpose, the mixture of leaves extract and AgNO3 solution were incubated at 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 min, respectively along with a Control. Fig. 1b shows the color change of reaction mixture with respect to time. Color change was visible after 10 min of reaction, from colorless to light yellow, which indicated the formation of AgNPs. As time elapsed, the yellow colored solution eventually turned to brown after 60 min, due to the increasing concentration and size of AgNPs. It was observed that the reduction of silver ions to AgNPs occurs quite rapidly, as more than 90% of the bioreduction reaction occurred within 60 min of the reaction. There was no significant change was beyond 60 min, therefore indicating the completion of the reduction reaction. This was further confirmed by UV–Vis spectroscopic analysis. This physical appearance of the reaction mixture turning from yellow to brown is due to the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) of the silver nanoparticles, which is considered to be the primary signature of the formation of AgNPs.

Besides, in other set of experiments different concentrations of AgNO3 was used to study the effect of reactant on the formation of AgNPs. All the reactions were performed at 85 °C by keeping the concentration of leaves extract constant (1 mL). The concentration of AgNO3 has considerable effect on the yield of resultant AgNPs. With increasing concentration of AgNO3, the intensity of the characteristic SPR peak of AgNPs also increased, but no change is observed in the position of the absorption peak (Fig. 1c). This clearly reveals that, the concentration of AgNO3 does not affect the size of AgNPs. Typically, with increasing the concentration of AgNO3 by keeping other variable constant, the intensity of the SPR peak is also increases due to the increasing yield of AgNPs (Yang et al., 2011). However, in this case, this trend is followed up to a certain concentration (<2 mM), while, upon using higher concentration (>2 mM) of AgNO3, no SPR peak was observed. This may suggest that either the reaction may not have occurred or possibly smaller amount of AgNPs may have formed, but the presence of large concentration of Ag+ ions might have suppressed the SPR peak of resultant AgNPs.

Furthermore, to study the effects of leaves extract concentrations on the formation of AgNPs, different experiments were performed with various concentrations of leaves extract and keeping all other variables constant. Upon addition of leaves extract into the aqueous solution of AgNO3, the color of the mixture is gradually changed from light yellow to brown depending upon the concentration of leaves extract. However, in the absence of leaves extract, no change in the color of reaction mixture was observed even after long time. This clearly confirms the role of leaves extract as bioreductant. As the concentration of leaves extract is varied from 0.1 to 1.5 mL, the positions of the SPR bands (from 406 to 409 nm) do not change significantly (Fig. 1d). Nonetheless, with increasing concentration of leaves extract, the intensity of SPR band increased remarkably, which points towards the higher yields of AgNPs. The small shift and broadening of SPR peaks caused by the variation in the amount of leaves extract can be attributed to the slight increase in the particle size and the aggregation of nanoparticles.

3.2 X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis

The crystalline nature of as-prepared AgNPs was examined using XRD. Fig. 2(B) shows the XRD pattern of AgNPs synthesized using leaves extract (1 mL) of A. indica at 85 °C for 30 min. XRD result confirms the crystalline nature of the sample. The diffractogram consists of five distinct reflections at 37.80° (1 1 1), 44.33° (2 0 0), 63.71° (2 2 0), 76.89° (3 1 1), and 81.33° (2 2 2). Thus the XRD spectra of the nanoparticles derived from A. indica leaves extract confirmed the formation of AgNPs. Notably, the XRD pattern also displays some extra peaks which are unassigned. Although, the results show that the main phase is silver; however there may be other crystalline phases belonging to the inorganic moieties of leaves extract which also contribute to the XRD pattern as impurities. For instance, several other studies regarding the green synthesis of AgNPs using plant extracts have also reported the existence of similar extra peaks in the XRD pattern of AgNPs (Marslin et al., 2015). These peaks were attributed to the crystalline impurities of the left over leaves extracts present on the surface of resultant nanoparticles (Awwad et al., 2013).

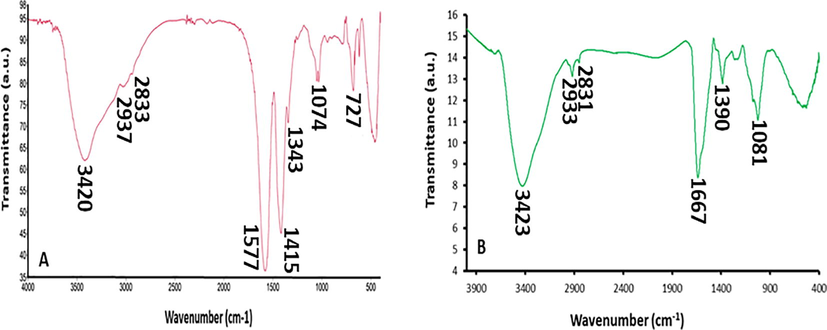

3.3 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis

Furthermore, FTIR spectroscopy was used to confirm the presence of residual phytomolecules of leaves extract on the surface of AgNPs as stabilizing ligands. Fig. 3, shows the FTIR spectra of the aqueous leaves extract of A. indica and as-prepared AgNPs. The AgNPs sample was carefully prepared for the FTIR analysis by repeatedly washing the sample to exclude any possibility of the presence of unbound phytomolecules on the surface of AgNPs. Notably, the IR spectra of both the samples appeared almost similar to each other, except the IR peaks in the case of AgNPs appeared less intense and showed marginal shift in their peak position. These striking similarities between the IR spectra of both the samples clearly confirm the dual role of the leaves extract as bioreducing and stabilizing agent. Besides some other functional groups, these spectra have prominently indicated towards the presence of hydroxyl (O—H stretching, ∼3,420 cm−1), aldehyde (C—H stretching, 2901 cm−1), phenolic (C⚌C stretching, ∼1,577 cm−1), aromatic (C—O/C—H bending ∼1415 cm−1) and geminal methyl groups (C—H bending, 1343 cm−1). Hence, this indicates that the phytochemical constituent of A. indica leaves extract is rich in terpenoids, flavonoids and polyphenols, which are known to possess excellent reducing abilities. Indeed, this is also confirmed by earlier studies which have identified the presence of different types of flavonoids, polyphenols and amino acids including quercetin, nimbolin, flavonone, glutamic acid and various other active phytomolecules in the A. indica leaves extract (Subapriya and Nagini, 2005). Possibly, the hydroxyl groups of these phytomolecules played a major role in the reduction of Ag ions to form AgNPs.

(A) FT-IR spectrum of pure A. indica leaves extract and (B) FT-IR spectrum of biosynthesized AgNPs using A. indica leaves extract.

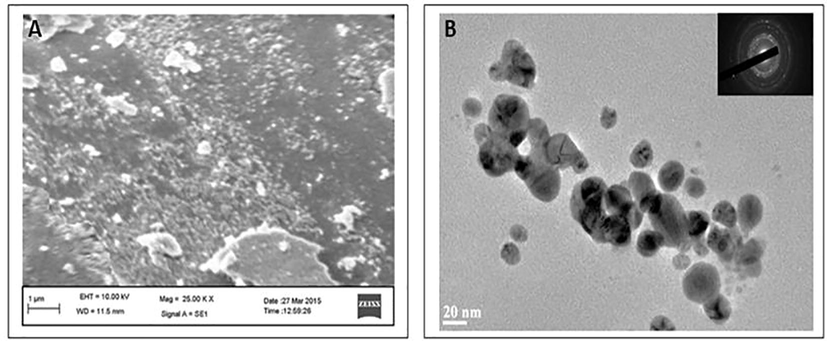

3.4 SEM and TEM analysis

Apart from this the size and morphology of as-prepared AgNPs was determined using Scanning electron Microscopies (SEM) and transmission electron Microscopies (TEM) methods. The SEM image in (Fig. 4(A)) shows that the synthesized AgNPs are in aggregate form. The nanoparticles that were observed with SEM were in the size range of 20–50 nm in which majority of them were in spherical shapes, while some other shapes have also been observed including triangular and cuboidal etc. The TEM image (Fig. 4(B)) also indicated that most of the AgNPs synthesized using A. indica leaf extract were spherical in nature with an average particle size in the range of 20–50 nm. Evidently, the size of the nanoparticles obtained from TEM is in accordance with the size predicted from UV–visible spectrum at 409 nm indicating that the average size of the biosynthesized AgNPs is approximately 20 nm. Therefore, it can be inferred that a significant proportion of biosynthesized AgNPs using leaves extract of A. indica are spherical in shape within the range of 20 nm.

(A) The SEM image of biosynthesized AgNPs (B) TEM micrograph of biosynthesized AgNPs using A. indica leaves extract. The average range of TEM biosynthesis of AgNPs was observed diameter was 20 nm.

3.5 Antimicrobial assay of biosynthesized AgNPs

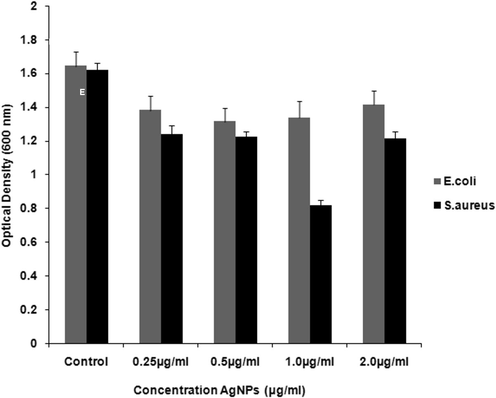

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) values of AgNPs against E. coli and S. aureus were evaluated to determine the lowest concentration of AgNPs that can cause the inhibition of the visible growth of the bacteria. E. coli and S. aureus were subjected to different concentrations of AgNPs (0.25 µg/mL, 0.5 µg/mL, 1.0 µg/mL, 2.0 µg/mL) and were also taken as control without AgNPs. The AgNPs showed highest activity against E. coli with the MIC value of 0.5 µg/mL while for S. aureus the MIC value was found to be 1.0 µg/mL. This indicates that the AgNPs prepared in this study are selective towards the gram negative bacterial strain E. coli (0.5 µg/mL) than towards S. aureus (1.0 µg/mL), a gram positive bacterium (Fig. 5). It was noticed that 2.0 μg/mL of AgNPs may have influence on OD 600. However, it can be said that the A. indica leaves extract synthesized AgNPs display biocidal activity against both gram positive and gram negative bacterial strains, and the results obtained are graphically illustrated in the Fig. 5.

Bar chart histogram indicates the antibacterial effect of biosynthesized AgNPs using Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (Control without AgNPs, 0.25 μg/mL, 0.5 μg/mL, 1.0 μg/mL and 2.0 μg/mL) against E. coli and S. aureus bacteria.

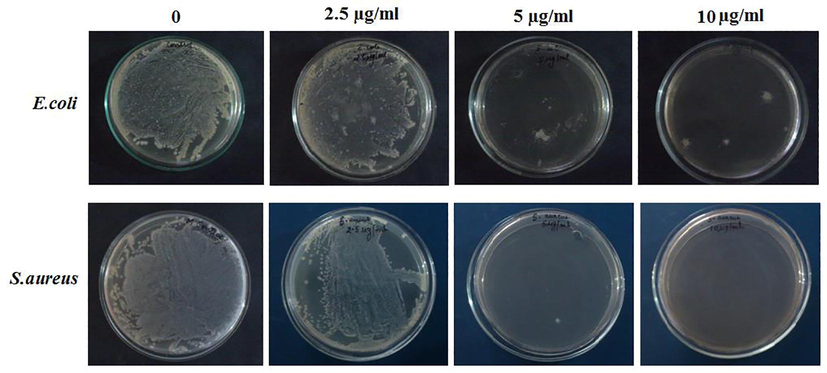

In this study, the antimicrobial properties of biosynthesized AgNPs were tested on gram-negative bacteria E. coli and gram-positive bacteria S. aureus employing various concentrations of AgNPs (0, 2.5, 5 and 10 µg/mL) (Fig. 6). It was observed that with increasing the concentration of AgNPs, there was a decrease in the presence of both E. coli and S. aureus. The AgNPs, at concentration of 10 µg/mL was able to inhibit the complete growth of S. aureus. While, the concentration of 5 μg/mL and 10 μg/mL of AgNPs were required to completely killed the S. aureus which is very clearly visualized from the complete absence of colony formation in the plates. Whereas, the E. coli showed a very few colony at 10 µg/mL. Hence it can be said that the A. indica leaves extract synthesized AgNPs at concentrations of 5 μg/mL and 10 μg/mL can achieve a good antimicrobial activity against both E. coli and S. aureus.

Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus bacteria on biosynthesized AgNPs at different concentration (0, 2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL).

3.6 AgNPs induced cytotoxicity in acute lymphocytic leukemia cells

Furthermore, the in vitro cytotoxic effect of as-prepared AgNPs against acute lymphocytic leukemia cells has also been investigated. The peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMCs) from human acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) patients were isolated for the cytotoxicity effect of the AgNPs employing MTT assay and which revealed that the AgNPs displayed cytotoxic effect against acute lymphocytic leukemia. During the study, the ALL cells were treated for 24 h with various concentrations of biosynthesized AgNPs between 15.6 µg/mL to 250 µg/mL and higher concentration (250 µg/mL) significantly had more toxic effect on cell viability, while the least toxic effect was observed at 15.6 µg/mL. The results obtained are illustrated graphically in Fig. 7.![MTT assay: Cytotoxic effect of synthesized AgNPs on PBMCs of cancer patients. Cells were treated with different concentration of AgNPs and incubated for 24 h and Cytotoxicity was determined by the MTT (3-[4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay.](/content/185/2020/32/1/img/10.1016_j.jksus.2018.09.014-fig8.png)

MTT assay: Cytotoxic effect of synthesized AgNPs on PBMCs of cancer patients. Cells were treated with different concentration of AgNPs and incubated for 24 h and Cytotoxicity was determined by the MTT (3-[4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay.

3.7 Discussion

In this study, biosynthesis of AgNPs was performed using the aqueous extract of A. indica leaves, which was collected from the southern region of India. During this study various parameters including time, temperature; AgNO3 concentration and A. indica leaf extract concentration, which may contribute to the reduction potential and quality of the resultant AgNPs is investigated in detail. The synthesis of AgNPs was performed by mixing the leaves extract with AgNO3 at 85 °C for 30 min, while the color change from colorless to faint yellow, indicated the formation of AgNPs. This was further confirmed by UV–Vis spectroscopic analysis. The results obtained were in complete agreement with previous reports on reduction of silver ions (Khalil et al., 2014). The physical appearance of the reaction mixture turning from yellow to brown is due to the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) of the silver nanoparticles, which is considered to be the primary signature of AgNPs formation. A recent study, also confirmed the effect of temperature on the reduction rate of Ag+ ions which resulted in the formation of AgNPs with small size (Sathishkumar et al., 2012). In this case, similar distinct relation between the temperature and the size and yield of synthesized AgNPs has also been observed. Apart from this, the time, concentrations of leaves extract and AgNO3 have also exerted significant effect on the quality and yield of resultant AgNPs, as observed in earlier studies (Bindhu and Umadevi, 2013; Khan et al., 2013). Besides, the FT-IR spectroscopy was useful in identifying the functional groups found in the phytomolecules of leaves extract and in assessing the bioreduction of as-prepared AgNPs.

Biosynthesized AgNPs were evaluated for their antibacterial activity against gram-negative E. coli and gram-positive S. aureus by using various concentrations of AgNPs such as 0, 2.5, 5, 10 µg/mL. Biosynthesized AgNPs at a concentration of 10 µg/mL was able to inhibit the growth of E. coli, whereas AgNPs with concentration 5 µg/mL, display a complete growth inhibition against S. aureus. The results obtained are in accordance to the earlier reported studies wherein the bacterial strain S. aureus was found to be more sensitive to AgNPs as compared to E. coli (Khalil et al., 2014). This variation in the response of the bacterial strains towards AgNPs is attributed to the differences in the thickness and constituents of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial membrane structure (Kim et al., 2007; Ravikumar et al., 2010). Besides, the cytotoxicity of biosynthesized AgNPs was evaluated employing the MTT assay, which revealed that the biosynthesized AgNPs with higher concentration (250 µg/mL) had significantly more toxic effect on cell viability of the ALL cells treated; suggesting that AgNPs mediated cell death is concentration-dependent manner.

4 Conclusion

The present study demonstrated a clean, non-toxic, eco-friendly method for the synthesis of AgNPs using A. indica leaves extract as reducing agents. Using this method highly crystalline, spherical shaped AgNPs were obtained under ambient conditions. Various physicochemical parameters including temperature, time, concentration of leaves extract and AgNO3 had clear effect on the quality and yield of the resultant AgNPs. Moreover, the current results and evaluation of earlier studies have indicated that the geographical location of A. indica plant also have critical role on the properties of resultant AgNPs. However, this needs to be further investigated with the combine efforts of natural product chemists and material scientists. Furthermore, the evaluation of the antibacterial activity of resultant AgNPs against pathogenic bacteria has suggested that the biosynthesized AgNPs display bactericidal properties, however the studies can be further extended to resistant strains and interesting results may be obtained. Moreover, in this study, in vitro effect of biosynthesized AgNPs on PBMCs from ALL patients has been evaluated for the first time. The results divulge the inhibiting property of the biosynthesized AgNPs against the proliferation of leukemic cells which can be further studied against various other cell lines in order to ascertain it as a viable therapeutic option. The suggested studies are being carried out and the extension of the work presented will be published as a separate study later.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through the research group project No. RG-1436-032.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica aqueous leaf extract. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci.. 2016;9:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity against gram positive and gram negative bacteria of biomimetically coated silver nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2011;27:9165-9173.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against MSSA and MRSA on isolates from skin infections. Biol. Med.. 2011;3:141-146.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intrinsic therapeutic applications of noble metal nanoparticles: past, present and future. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2012;41:2943-2970.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using carob leaf extract and its antibacterial activity. Int. J. Ind. Chem.. 2013;4:29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bottom-up, wet chemical technique for the continuous synthesis of inorganic nanoparticles. Inorganics. 2014;2:1-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of monodispersed silver nanoparticles using Hibiscus cannabinus leaf extract and its antimicrobial activity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2013;101:184-190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival: modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. J. Immunol. Methods. 1986;89:271-277.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles having significant antimycotic potential against plant pathogenic fungi. J. Bionanosci.. 2012;6:90-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- The unique role of nanoparticles in nanomedicine: imaging, drug delivery and therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2012;41:2885-2911.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antitumor activity of colloidal silver on MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.. 2010;29:148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nonclassical CD1d-restricted NK T cells that produce IL-13 characterize an atypical Th2 response in ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Investig.. 2004;113:1490-1497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alfalfa sprouts: a natural source for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2003;19:1357-1361.

- [Google Scholar]

- The apoptotic effect of nanosilver is mediated by a ROS-and JNK-dependent mechanism involving the mitochondrial pathway in NIH3T3 cells. Toxicol. Lett.. 2008;179:130-139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metallic nanostructures as localized plasmon resonance enhanced scattering probes for multiplex dark-field targeted imaging of cancer cells. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:2676-2684.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Fusarium acuminatum and its activity against some human pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Nanosci.. 2008;4:141-144.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancement of the antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles using β-cyclodextrin as a capping agent. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2010;36:280-283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of size-dependent antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014

- [Google Scholar]

- Metal nanoparticle generation using a small ceramic heater with a local heating area. J. Aerosol Sci.. 2006;37:1662-1670.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using olive leaf extract and its antibacterial activity. Arabian J. Chem.. 2014;7:1131-1139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated by Pulicaria glutinosa extract. Int. J. Nanomed.. 2013;8:1507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology. Biol. Med.. 2007;3:95-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of geographic variations of Origanum vulgare trichomes and essential oil content in Greece. Biochem. Syst. Ecol.. 1994;22:517-528.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles produced using Arbutus unedo leaf extract. Mater. Lett.. 2012;76:18-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Individual inorganic nanoparticles: preparation, functionalization and in vitro biomedical diagnostic applications. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2013;1:1381-1396.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2010;26:615-621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of cream incorporated with silver nanoparticles biosynthesized from Withania somnifera. Int. J. Nanomed.. 2015;10:5955.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of antimicrobial silver nanoparticles by callus and leaf extracts from saltmarsh plant, Sesuvium portulacastrum L. Colloids Surf., B. 2010;79:488-493.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticle using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and its anti-microbial activity. J. Alloy. Compd.. 2014;583:272-277.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parthenium leaf extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles: a novel approach towards weed utilization. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. (DJNB). 2009;4

- [Google Scholar]

- Metallic nanoparticles: microbial synthesis and unique properties for biotechnological applications, bioavailability and biotransformation. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol.. 2015;35:114-128.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol. Adv.. 2009;27:76-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent progress in the synthesis of inorganic nanoparticles. Dalton Trans.. 2012;41:5089-5120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial potential of chosen mangrove plants against isolated urinary tract infectious bacterial pathogens. Int. J. Med. Med. Sci.. 2010;2:94-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and its antimicrobial study. Appl. Nanosci.. 2017;7:843-850.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phyto-synthesis of silver nanoscale particles using Morinda citrifolia L. and its inhibitory activity against human pathogens. Colloids Surf., B. 2012;95:235-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Properties and applications of colloidal nonspherical noble metal nanoparticles. Adv. Mater.. 2010;22:1805-1825.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geranium leaf assisted biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles. Biotechnol. Prog.. 2003;19:1627-1631.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid synthesis of Au, Ag, and bimetallic Au core–Ag shell nanoparticles using Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf broth. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2004;275:496-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ayurvedic Drugs and Their Plant Sources. Oxford and IBH publishing; 1994.

- Studies on surface plasmon resonance and photoluminescence of silver nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2008;71:186-190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial and cytotoxic effect of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles using aqueous root extract of Erythrina indica lam. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2015;135:1137-1144.

- [Google Scholar]

- Process for isolation of hepatoprotective agent “oleanolic acid” from Lantana camera. Google Patents 2005

- [Google Scholar]

- Medicinal properties of neem leaves: a review. Curr. Med. Chem.-Anti-Cancer Agents. 2005;5:149-156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic effect of Green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach against in vitro HeLa cell lines and lymphoma mice model. Process Biochem.. 2012;47:273-279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, properties, toxicology, applications and perspectives. Adv. Nat. Sci.: Nanosci. Nanotechnol.. 2013;4:033001

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized by aqueous extract of Azadirachta indica (Neem) leaves. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol.. 2009;5:93-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Process variables in biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles by aqueous extract of Azadirachta indica (Neem) leaves. J. Nanopart. Res.. 2010;12:237-246.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological reduction of silver nanoparticles using Cassia auriculata flower extract and evaluation of their in vitro antioxidant activities. Nanosci Nanotechnol Int J. 2012;2:30-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethnobotanical survey of Zagori (Epirus, Greece), a renowned centre of folk medicine in the past. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1993;39:187-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver nanoplates: from biological to biomimetic synthesis. ACS Nano. 2007;1:429-439.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis of high-concentration, stable aqueous dispersions of uniform silver nanoparticles using aniline as a reductant. Langmuir. 2011;27:5047-5053.

- [Google Scholar]