Translate this page into:

Assessment of radiation dose for dental workers in Saudi Arabia (2015–2019)

⁎Corresponding author. Yalashban@ksu.edu.sa (Y. Alashban)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study is to estimate the annual average effective dose for dental workers in Saudi Arabia from the period of 2015 to 2019. Also, to compare the average annual effective doses received with the International Commission of Radiological Protection limits.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on radiation doses for 2,128 dental workers. Their radiation doses were monitored by using Thermoluminescent dosimeters.

Results

The annual average effective dose was in the ranges of 0.44–1.04 mSv. A two-tailed independent samples t-test (α = 0.05) was used to compare the means of the effective doses for dentists and dental nurses. There was not enough evidence to conclude that dentists’ scores (M = 0.79, SD = 0.49) were any different from dental nurses’ scores (M = 0.77, SD = 0.46), t (2126) = 0.58, p = 0.55.

Conclusions

The annual average effective dose, averaged over the five years, was found to be 0.72 mSv. All of the workers received occupational doses below the annual effective dose limit. These results of annual mean effective doses are a good indicator of dental radiation safety practices in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords

Occupational dose

Radiation dosimetry

Effective dose

Dental workers

- IR

-

Ionizing radiation

- RPP

-

Radiation Protection Program

- TLD

-

Thermoluminescent dosimeter

- ACED

-

Annual collective effective dose

- AAED

-

Annual average effective dose

- SE

-

Standard error

- SD

-

Standard deviation

- MDL

-

Minimum detectable limit

- ALARA

-

As low as reasonably achievable

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Ionizing radiation (IR) is widely used in many fields including medical, research, and industrial applications. Workers in these fields can be exposed to IR, which can pose health risks such as cancer and cataract (Linet et al., 2010; Milacic, 2009). In the medical field, the radiation dose is received when performing diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. Medical staff can be exposed to low-level radiation over a long period of time (chronic exposure), which can be associated with biological effects (Sahin et al., 2009; Covens et al., 2012).

Dentistry is one of the occupations involving chronic exposure to IR (UNSCEAR, 2016). It was reported in several studies that IR is one of the major occupational risks among dentists (Mehta et al., 2013; Sont et al., 2001; Leggat et al., 2007). Advancements in radiographic technologies and radiation protection practices have played an important role in decreasing radiation exposure to the workers (Linet et al., 2010; Leggat et al., 2001). However, there has been an increase in the number of diagnostic procedures and thus an increase in the occupational radiation dose (Smith-Bindman et al., 2008). In dental radiology, the number of radiographs is rising worldwide. According to The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, 340 million dental radiology examinations were performed globally in 1988. This number increased in 2008 to approximately 480 million, which comprises 15% of all diagnostic x-ray examinations in health care (UNSCEAR, 2008). Due to high exposure radiation, deterministic effects to dentists’ fingers have been reported. This is a result of dentists holding the film in patients’ mouths (Monsour et al., 1988; Wagner and Archer, 1988). Radiation exposures to dental x-rays have been found to be linked with an increased risk of thyroid cancer (Memon et al., 2010), brain cancer (Picano et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2012; Claus et al., 2013), and salivary gland tumors (Preston-Martin and White, 1990; Horn-Ross et al., 1997; Preston-Martin et al., 1988).

Monitoring radiation exposure by personal dosimeters is recommended if the dental professionals receive an annual effective dose above 1 mSv (NCRP, 2019). The recommended dose limits for radiation workers, including dental workers, are as follows: 20 mSv for annual effective dose (whole-body), 20 mSv annual equivalent dose to the lens of the eye, and 500 mSv for an annual equivalent dose to the extremities (hands and feet) or the skin. The dose limit for a declared pregnant worker is 1 mSv, which is equivalent dose to the fetus per month (ICRP, 2007, 2012). Dental professionals receive less exposure to IR than other occupationally exposed medical workers (ADA, 2012; Lee et al., 2009). The purpose of this study is to investigate occupational radiation exposure to dental workers in Saudi Arabia.

2 Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on annual effective dose for 2,128 dental workers in Saudi Arabia from 2015 to 2019. The workers were distributed across 43 dental centers and hospitals in all 13 Saudi administrative regions: Riyadh region, Makkah region, Madinah region, Qassim region, Eastern region, Asir region, Tabuk region, Hail region, the Northern Border region, Jazan region, Najran region, Al Baha region, and Al Jouf Region.

The Radiation Protection Program (RPP) of the Saudi Ministry of Health maintains records of all workers’ radiation doses. There is information pertaining to the name, gender, national identification number, quarterly radiation dose, and occupation of each individual worker. Dental workers were grouped into two occupational categories: dentists and dental nurses. Their radiation doses were monitored by using whole-body Thermoluminescent dosimeters (TLD-100) made of Harshaw detector crystal of LiF:Mg,Ti elements. Quarterly, TLD badges were collected and analyzed using a Harshaw model 6600, plus an automated TLD reader. For calibration and quality control analysis, the reader was calibrated under reproducible reference situation using an internal irradiator a 90Sr/90Y, with a radiation activity of 0.50 mCi, was used. The sensitivity of the reader has a range of 10 μGy to 1 Gy, with a linearity of about 5% and a minimum detectable limit (MDL) of 1 μSv. Also, the time temperature profile had a 120o C preheated temperature and an acquisition temperature rate of 20o C/s up to 390o C. The reading system used a purified nitrogen source with a pressure that ranged from 40 to 95 psi. The ideal flow rate mode of the reader is 28 l/h.

The TLD readings were analyzed by using a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 20 (SPSS‑Inc., Chicago, IL).

3 Results

Of the 2,128 dental workers, 45% were dentists and 55% were dental nurses. The female workers accounted for 62% of dental workers, while the male workers accounted for just 38%. Approximately 60% of the dental workers worked in densely populated provinces, such as: Riyadh province, Eastern province, Makkah province, and Asir province. The most frequent imaging procedures performed in these dental centers were panoramic x-ray, followed by intraoral x-ray, cephalometric x-ray, and cone-beam computed tomography. Panoramic x-ray is widely used since it screens a wider area than regular intraoral x-ray procedures. Therefore, this procedure can provide beneficial information about multiple oral issues such as maxillary sinuses, tooth positioning and bone abnormalities. Table 1 shows the number of occupationally exposed dental workers, their annual collective effective dose, and the annual average effective dose during 2015–2019.

Occupation

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

Dentist

No. of workers

97

134

140

262

318

ACED (person-mSv)

80.23

73.95

99.11

189.32

325.14

AAED (mSv)

0.82

0.55

0.70

0.72

1.02

Dental Nurse

No. of workers

146

179

168

327

357

ACED (person-mSv)

64.56

100.41

127.51

236.74

371.76

AAED (mSv)

0.44

0.56

0.75

0.72

1.04

Total

No. of workers

243

313

308

589

675

ACED (person-mSv)

144.79

174.36

226.62

427.06

696.9

AAED (mSv)

0.59

0.55

0.73

0.72

1.03

Table 2 represents the mean, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation for the effective dose for all the workers during 2015–2019. The results revealed that the highest annual effective dose reported was 7.39 mSv for a male dentist in 2015.

Occupation

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

Dentist

Mean ± SE

0.66 ± 0.07

0.55 ± 0.03

0.70 ± 0.02

0.72 ± 0.02

1.02 ± 0.02

Minimum

0.10

0.09

0.07

0.11

0.08

Maximum

7.39

2.87

1.98

2.48

3.20

SD

0.76

0.38

0.33

0.35

0.49

Dental Nurse

Mean ± SE

0.54 ± 0.03

0.56 ± 0.02

0.75 ± 0.02

0.72 ± 0.2

1.04 ± 0.02

Minimum

0.10

0.11

0.13

0.04

0.04

Maximum

3.89

1.62

3.09

2.95

4.00

SD

0.38

0.28

0.35

0.39

0.53

Total

Mean ± SE

0.59 ± 0.03

0.55 ± 0.01

0.73 ± 0.01

0.72 ± 0.01

1.03 ± 0.01

Minimum

0.10

0.09

0.07

0.04

0.04

Maximum

7.39

2.87

3.09

2.95

4.00

SD

0.57

0.32

0.34

0.38

0.51

The number of dental workers were distributed into five effective dose intervals, which are: minimum detectable limit (MDL) – 0.49 mSv, 0.50–0.99 mSv, 1–1.99 mSv, and

3 mSv as illustrated in Table 3.

Year

MDL – 0.49 mSv

0.50 – 0.99 mSv

1.00 – 1.99 mSv

2 – 2.99 mSv

3 mSv

2015

118

106

17

0

2

2016

147

140

25

1

0

2017

75

169

63

0

1

2018

165

306

113

5

0

2019

68

324

247

32

3

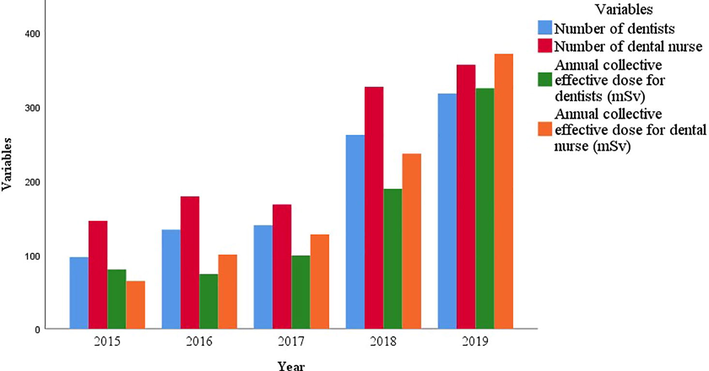

The results of the annual collective effective doses and number of dental workers are schematically shown in Fig. 1.

Annual collective effective dose associated with the number of dental workers.

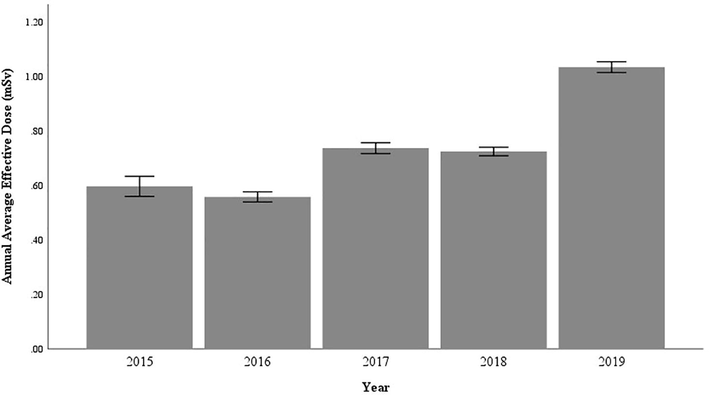

As shown in Fig. 2, the annual average effective dose for the dental workers did not obey a specific trend during the 5-year study period. The lowest and the highest annual average effective doses were found to be 0.55 mSv in 2016 and 1.03 mSv in 2019 respectively.

Annual average effective dose for dental workers in the period of 2015–2019 at α = 0.05.

4 Discussion

During the study period, the annual average effective dose was in the range of 0.55–1.02, and 0.44–1.04 mSv for dentists and dental nurses respectively. The annual average effective dose over the period of five years for all of the dental workers was found to be 0.72 mSv.

By comparing dentists and dental nurses, the annual effective doses, averaged over the study period for both, were 0.76 and 0.70 mSv respectively. These numbers show that dentists received about 8% more radiation dose than the dental nurses. The interest was in determining a significant mean difference between dentists and dental nurses in terms of effective dose. As such, a two-tailed independent samples t-test (α = 0.05) was used to compare the means. The comparison results were not significant. There is not enough evidence to conclude that dentists’ doses (M = 0.79, SD = 0.49) are any different from dental nurses’ doses (M = 0.77, SD = 0.46), t (2126) = 0.58, p = 0.55.

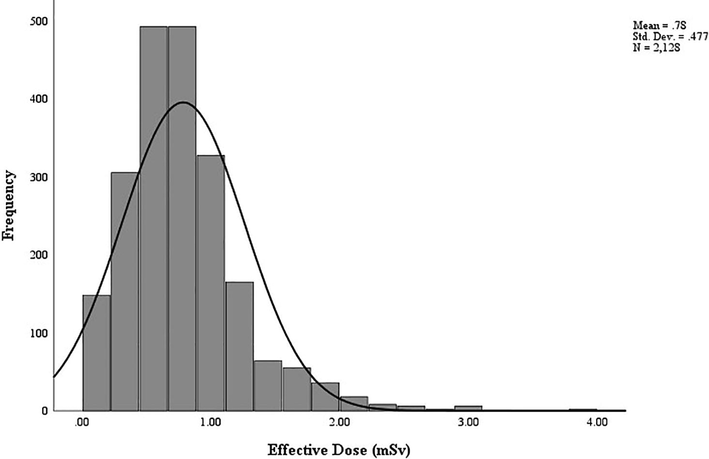

During the 5-year study period, there was no incidence of a dose above the annual dose limit of 20 mSv for all of the dental workers. Fig. 3 shows the frequency of the effective dose for all workers combined during 2015–2019 with the normal distribution curve. The results showed that more than 76% of the workers received an annual effective dose of less than 1 mSv, while just less than 2% received an annual effective dose of more than 2 mSv.

Frequency of the effective dose for all workers combined during 2015–2019 with the normal distribution curve.

A two-tailed independent samples t-test was used to compare the mean difference in effective doses between the male workers (n = 809) and the female ones (n = 1319). The Type I error rate was set at alpha = 0.05. The results suggest that the average effective dose is greater for males (M = 0.82, SD = 0.49) than for females (M = 0.76, SD = 0.46), t (2126) = 2.73, p = 0.006.

The results indicated an increase in the annual collective dose, mainly in 2018 and 2019 due to an increase in the number of workers. The highest collective dose for all workers was found to be 697 person-mSv in 2019.

The comparative analysis of the annual average effective doses in dentistry for different countries is illustrated in Table 4 (UNSCEAR, 2008). Regardless of the differences in the data range, the table provides a rough assessment of the occupational radiation dose.

Data range

Country

Annual average effective dose (mSv)

1995–1999

Chile

1.40

2000–2002

Japan

1.52

2000–2002

Canada

0.79

2000–2002

Spain

0.98

2000–2002

Greece

1.05

1990–1994

Worldwide

0.89

2015–2019

Saudi Arabia (current study)

0.72

The dose values for this study are an indication of improved radiation protection practices compared to other countries in previous years. This improvement is due to many factors, such as: keeping the dental clinics up to date with new radiation protection policies, using high efficiency dental radiography machines, raising staff awareness about the importance of using adequative radiation protection equipment, and having access to the latest radiology literature. The RPP in Saudi Arabia requires full quality control tests to ensure that radiation protection for patients, workers, and the public is optimal.

5 Conclusion

This study is the first of its kind to provide a reference of the effective dose for dental workers in Saudi Arabia. During 2015–2019, all of the workers received occupational doses below the annual effective dose limit. In agreement with the ALARA principle, the occupational doses were spread towards a low dose range. The annual effective dose, averaged over the study period for all of the dental workers, was found to be 0.72 mSv. The results showed that there is no significant difference for the annual effective dose between dentists and dental nurses. More than 76% of the workers received an annual effective dose of less than 1 mSv. The highest collective dose was found to be 697 person-mSv in 2019. The lowest and the highest annual average effective doses were found to be 0.55 mSv in 2016 and 1.03 mSv in 2019 respectively.

By comparing the results in this study with others in the literature, it can be concluded that, in general, dental workers are exposed to lower doses in Saudi Arabia than in Chile, Japan, Canada, Spain, and Greece. Moreover, the annual average effective dose value in dentistry of worldwide (0.89 mSv) is greater than that for dental workers in Saudi Arabia (0.72 mSv). These results of annual mean effective doses are a good indicator of dental radiation safety practices in Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgement

Author extend their appreciation to the College of Applied Medical Sciences Research Center and Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this project.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- ADA, 2012. Dental radiographic examinations: recommendations for patient selection and limiting radiation exposure. Columbia. 01−21.

- Covens, P., Berus, D., de-Mey, J., Buls, N., 2012. Mapping very low level occupational exposure in medical imaging: a useful tool in risk communication and decision making. Eur. J. Radiol. 81, 962−966.

- Environmental factors and the risk of salivary gland cancer. Epidemiology.. 1997;8:414-419.

- [Google Scholar]

- ICRP, 2007. The 2007 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ann. ICRP. 103, 01−34.

- ICRP, 2012. ICRP statement on tissue reactions and early and late effects of radiation in normal tissues and organs–threshold doses for tissue reactions in a radiation protection context. Ann. ICRP, 01−322.

- Occupational hygiene practices of dentists in southern Thailand. Int. Dent. J.. 2001;51:11-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occupational health problems in modern dentistry: a Review. Ind. Health.. 2007;45:611-621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occupational radiation doses among diagnostic radiation workers in South Korea, 1996–2006. Radiat. Prot. Dosim.. 2009;136:50-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Historical review of occupational exposures and cancer risks in medical radiation workers. Radiat. Res.. 2010;174:793-808.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measures taken to reduce X-ray exposure of the patient, operator, and staff. Aust. Dent. J.. 1988;33:181-192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of occupational radiation-induced cataract in medical worker. Med. Lav.. 2009;1:178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dental x-rays and the risk of thyroid cancer: a case-control study. Acta. Oncologica.. 2010;49:447-453.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of occupational hazards and their prevention among dental professionals in Chandigarh, India: A comprehensive questionnaire survey. J. Dent. Res.. 2013;10:446.

- [Google Scholar]

- NCRP, 2019. Radiation protection in dentistry and oral & maxillofacial imaging. NCRP publication Report No. 177, Maryland, United States.

- Prior Exposure to medical and dental X-rays related to tumors of the parotid gland. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst.. 1988;80:943-949.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brain and salivary gland tumors related to prior dental radiography: implications for current practice. J. Am. Dent. Assoc.. 1990;120:151-158.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer and non-cancer brain and eye effects of chronic low-dose ionizing radiation exposure. BMC. Cancer.. 2012;12:157.

- [Google Scholar]

- First analysis of cancer incidence and occupational radiation exposure based on the National Dose Registry of Canada. Am. J. Epidemiol.. 2001;153:309-318.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rising use of diagnostic medical imaging in a large integrated health system. Health. Aff.. 2008;27:1491-1502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the genotoxic effects of chronic low-dose ionizing radiation exposure on nuclear medicine workers. Nucl. Med. Biol.. 2009;36:575-578.

- [Google Scholar]

- UNSCEAR, 2008. Effects of ionizing radiation. Report to the General Assembly, with Scientific Annexes, UN, New York.

- UNSCEAR, 2016. Sources, effects and risks of ionizing radiation. Report to the General Assembly, with Scientific Annexes, UN, New York.

- Wagner, L., Archer, B., 1988. Minimizing risks from fluoroscopic x rays bioeffects, instrumentation, and examination, second ed. R.M. Partnership, The Woodlands.