Translate this page into:

Assessment of inorganic ion in drinking water using new method based on ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

⁎Corresponding author. mrkhan@ksu.edu.sa (Mohammad Rizwan Khan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

Sulfite ion play a crucial role in the atmospheric environment, its presence in water system is very unsafe to both the human and food production due to the formation of acid after reaction with water (acid rain). In the current investigation, ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) method was used for the identification and quantification of sulfite ion in drinking water and the process was optimized. In this study, a reversed phase BEH C18 chromatography column was applied for the separation of sulfite ion using binary mobile phase comprising water and methanol (95:5, v/v), separation was attained in less than 1 min. Method validation parameters in terms of linearity (r2), limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ) and precision were established. The linearity (r2 > 0.999) and, LOD and LOQ were obtained 0.003 µg/mL and 0.01 µg/mL respectively. The precision in terms of relative standard deviation (RSD) was found to be < 3.5%. The validated standard methodology was used for the quantitative determination of sulfite ion in water obtained from different sources. The sulfite ion amounts were found between 2.21 µg/mL and 90.11 µg/mL water sample, and the recovery values were obtained between 97.55% and 104.49%. It was observed from the data that the quantified levels of sulfite ion were above the maximum contaminant levels (MCLs, 10 μg/mL) according to US Environmental Protection Agency in all 100% metropolitan water samples and about 82% of the analyzed bottled waters. In addition, the comparison of results obtained in water samples from Saudi Arabia with formerly stated data were carried out. The benefits of applying UPLC-MS as a new method in competition with other techniques are smaller analysis time (<1 min), tremendous accuracy and higher recovery values. Nonetheless, the sulfite was still detected in drinking water samples from Saudi Arabia. Hence, the detecting and decreasing the level of sulfite in water samples needed further apprehensions to meet better needs of strategies for consumer health.

Keywords

Sulfite ion

Bottled water

Metropolitan water

Maximum contaminant levels

Liquid chromatography

Mass spectrometry

- UPLC-MS

ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- LOD

limit of detection

- LOQ

limit of quantification

- RSD

relative standard deviation

- MCLs

maximum contaminant levels

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

The sulfur (IV) species, such as sulfite anion (SO32−) is the conjugate base of bisulfite. Its salts are widely used worldwide, mainly in food and pharmaceutical industries. In the food industries, sulfite ion has been used as food additives during the storage of dried fruit, salad, dried ginger, molasses, gelatine, garlic powder, dried potatoes, pickles, fruit juice, corn syrup, alcoholic and soft drinks. The use of sulfite ion in such foods help to avoid any kind of bacterial growth, enhance the flavor and preserve freshness of such food products (Koch et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2002; Ranguelova et al., 2013).

Besides, sulfite ion has been widely applied in boliler-feed and boilers to control the dissolved oxygen level (Beitollahi et al., 2014), and in sterilized bottles prior to packaging of foods or drinks (Lien et al., 2016). It has frequently been applied in medications industries to increase the shelf life of the medicines. Rather than these sulfite ion sources, it has the ability to be naturally grown in some foods and neutral liquids by the hydration of sulfur dioxide (Meng et al., 2004). Hence, due to the vast uses of this ion in food products and waters are considered as the major sources of sulfite ion contaminations.

Sulfite ion also play crucial role in the atmospheric environment (Zhao et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2018a). The presence of sulfite ion in water system is very harmful to both the human and the agricultural field (Zhao et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2018a). Because, it lead to the formation of acid after reaction with water (acid rain) (Kularatne et al., 2003). In addition, sulfite ion has identified as one of the vital substance since its presence in the water system degrades the water quality (Yin et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2018b). The co-contaminants including organic and inorganic substances present in the water reacts with sulfite ion and degrade the water quality (Yin et al., 2010; Dong et al., 2018). It has also been confirmed from the earlier epidemiological studies that the excess intake of this anions are poisonous and if enter into the body may cause lung and brain cancer, strokes, migraine headaches, asthamatic attacks and myochardial ischemia (Yin et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2014; Vally et al., 2009; Iwasawa et al., 2009; Sang et al., 2010; de Azevedo et al., 2007; Claudia and Francisco, 2009).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations agency has indicated and set the limit of the sulfite ion concentration in foods (≤10 mg/kg), beverages and liquids (≤10 mg/L). In the same time the agency recommends warning if the level is more than this specified limit (Satienperakul et al., 2010; Hassan et al., 2006; Yilmaz and Somer, 2007; Pundir and Rawal 2013, Fatibello-Filho and da Cruz, 1997; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 1986). Although, according to the FDA and Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) the sulfite ion is safe to consume but harmful even to low dose towards the asthmatics and liver or kidney dysfunction peoples (Satienperakul et al., 2010; Yilmaz and Somer, 2007; Vally et al., 2009).

Therefore, considering its many adverse effects towards human health and environmental, researches have been focused on sulfite ion analysis and given great attention towards its detection in various matrices. Till now, many detection methods were reported for the determination of sulfite ion in several foods and environmental products for instance spectrophotometry (Hassan et al., 2006; Segundo et al., 2000; Williams et al., 1981), elecrtochemical (Zelinsky, 2016), flow injection (Wang et al., 2011), fluorescent probes (Ding et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2017), capillary electrophoresis (Daunoravicius and Padarauskas, 2002), high performance liquid chromatography (McFeeters and Barish, 2003; Theisen et al., 2010). In recent years, many studies have also revealed the removal of sulfur species from various water sources (Iftekhar et al., 2018; Hong et al., 2017; Jain et al., 2017). Neverthless, most of these reported techniques faces limitations as sulfite ion can easily be oxidized to sulfate ion in samples and standards. Hence, it is quite difficult to make their precise determination especially by ion chromatography. To overcome such limitations, some techniques uses derivatization of sulfite ion solution using formaldehyde to make the sulfite ion stock solution stable. All these techniques are time consuming and requires tedious sample pretreatment. In addition, they suffer from lacking sensitivity and precision and not suitable for low sulfite ion concentration analysis. Hence, it is very important to develop rapid and highly sensitive method for the analysis of sulfite in water.

Until now, no methods was developed for the determination of sulfite ion based on analysis using mass spectrum. Thus, the main objective was to develp liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) based analysis to determine sulfite ion content in drinking water. This method provides sensitive and very fast detection of sulfite ion which directly fulfil the demand of low sample consumption and reduce loss of time during the analysis with higher efficiency (Wu et al., 2004; Samanidou et al., 2004). Also the method could be helpful to analyze the risk due to prolong exposure of sulfite ion.

2 Methods and materials

2.1 Reagents and chemicals

Analytical reagent (AR) grade reagents and solvents were applied for all experiments. The standard sodium sulfite ion (95% purity) was supplied by BDH chemical company (Poole, England). Acetonitrile, formic acid, methanol, ethanol, were also supplied by BDH chemicals company. The Ultrapure water (Milli-Q) was applied for the preparation of samples and also mobile phase used for analysis. Milli-Q water was obtained using a Millipore unit (Bedford, MA, USA). The filtration of the samples and standards were achieved using 0.22 μm PVDF syringe filter (Membrane Solutions, TX, USA).

2.2 Water sample collection

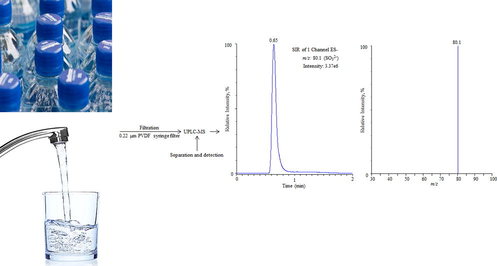

The bottled water of various brands and country origin was collected from the local retail markets at Saudi Arabia. The metropoliton water samples were collected from different cities, Saudi Arabia. The total number of water samples were twenty eight (22 bottled water and 6 metropolitan water), and before being analyzed they were stored at a temperature below 4 °C. All samples were passed through syringe filter before injection to the UPLC system.

2.3 Equipment

In our study, an Acquity ultra-performance LC-MS (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was applied for the identification and analysis of sulfite ions in drinking water samples. To determine the sulfite ion, BEH C18 column was used for analysis. Electrospray ionization source (ESI) was equiped with this MS for the determination of compound. An rotary pump has been attached to maintain vaccum to the MS. A nitrogen generator was used to produce nitrogen which was used as desolvation and used as nebulising agent and cone gas. Argon was applied as collision gas and was supplied by Specialty Gas Centre (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia). Data analysis was performed using MassLynx V4.1 software (Waters, Milford, MA, USA).

2.4 Sample analysis

Sulfite standard solution of 100 μg/mLwas prepared by suspending suitable amount of sodium sulfite in 500 mL of sulfite ion free Milli-Q water. The standard solutions between ranges 0.05 and 100 μg/mL were prepared by diluting the stock solution appropriately. The sulfite ion free Milli-Q water was used until otherwise stated. To avoid any degradation of the target analyte, fresh standard was stored in a amber colour vial. To evaluate the effectiveness of the technique and obstract the effect of matrix influence on analyte peak symmetry, retention time and intensity, the quantification of sulfite was carried using standard addition technique which consist two non-fortified samples (zero levels) and four fortified samples 50% (2.5 µg/mL, level illustrating the sulfite increase in the water sample after fortifying), 100% (5 µg/mL), 500% (25 µg/mL) and 1000% (50 µg/mL). Samples were investigated in triplicates (n = 3). A slope was used to explore the recovery values during determining the association between the added and achieved amounts of sulfite. The statistical analysis was carried out using ANOVA technique.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Optimization of UPLC-MS

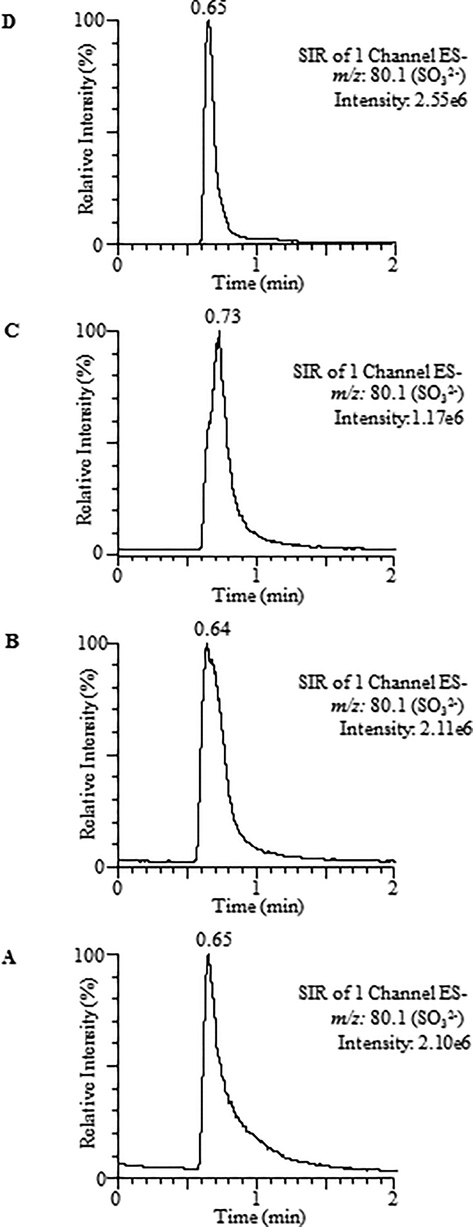

For the optimization of UPLC conditions, various analytical columns including C8 and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography at different column oven temperatures were tested. The best chromatographic signal of the target analyte was obtained with C18 column run at room temperature. These columns have better efficacy and did not affect even at the increased flow rates. In order to get the highest intensity and symmetrical peak, the mobile phase of various compositions were optimized. A number of solvents such as methanol, ethanol and acetonitrile individually and/or in combination were applied for this purpose. The high intense chromatographic peak was obtained using the binary mobile phase of composition of Milli-Q water and methanol was 95:5, v/v. The achieved outcomes have been shown in Fig. 1. The flow rate of the column was maintained as 0.20 mL/min. The dead volume of the system was 0.32 min and the target analyte was eluted at the retention time of 0.65 min. At higher flow rate the peak was appeared faster but the intensity of the peak response was decreased may be due to the presence of other ions which may come from mobile phases in the mass spectrometric source. As a result, the less ionization of the target analyte occurs and correspondingly its intensity decrease. To avoid any carryover, the blank samples were injected after each analysis, and no any retained compound was found. The injections were carried out with an auto-sampler, and the injection volume for both the standard and real samples was 5 µL.

Optimization of mobile phase (water and methanol) composition, (A) 60:40; (B) 70:30; (C) 90:10 and (D) 95:5.

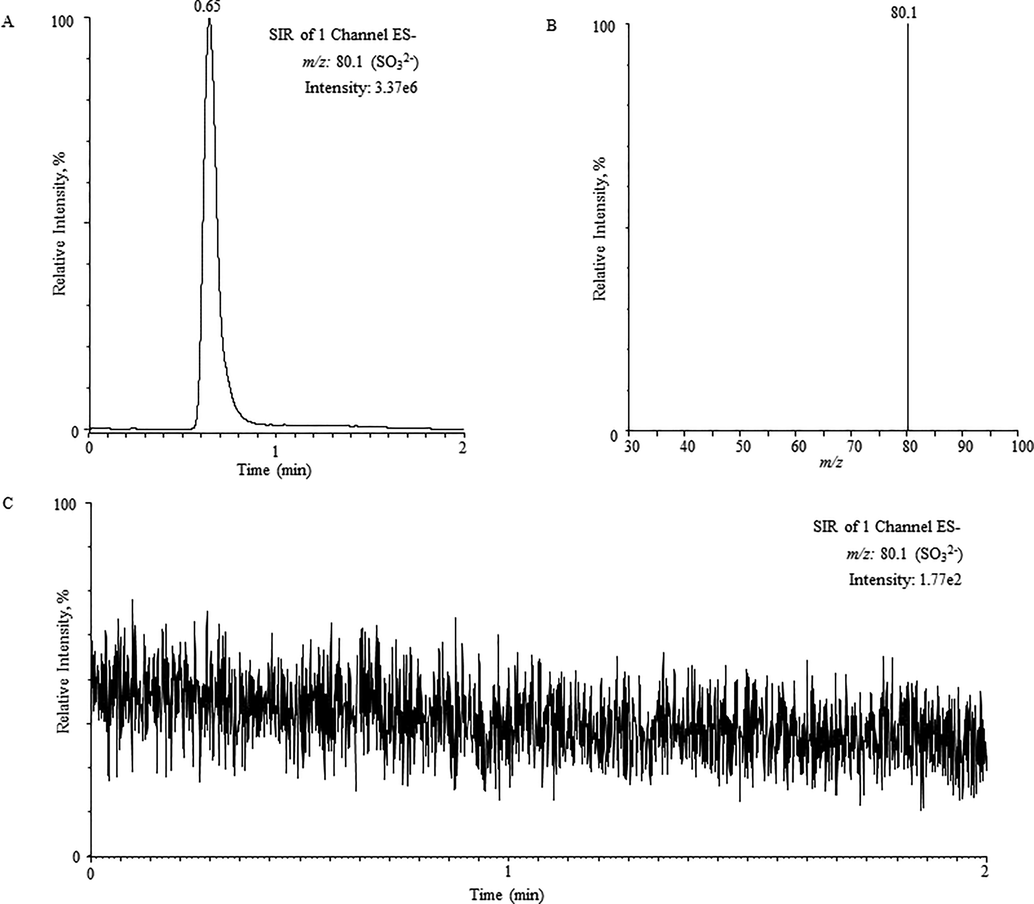

Initially, the mass spectrometric conditions were standardized by applying standard solution (10 µg/mL). In this experiment, negative and positive ionization modes was used to ensure high analyte response. At the electrospray positive inonization mode, different ion source parameters were tested, however no signal was detected. Thus, the electrospray negative ionization mode was applied and a highly intense ion peak was appeared. To achieve the highest intensity of the precursor ions various ion source conditions for instance capillary voltage (2.0–4.5 kV), cone voltage (5–110 V) and desolvation temperature (200–450 °C) were optimized, monitored by intellistart software program (MassLynx V4.1, Waters, USA). The optimized ion source conditions have been demonstrated in Table 1. The mass spectrometric conditions were carried out in SIR mode for the confirmation and quantitation of the target analyte. Based on the results the suitable SIR parameters for sulfite ion are described in Table 2, and the SIR chromatogram of the target analyte and blank solution (Milli-Q water) using optimal tuning and liquid chromatographic conditions are given in Fig. 2.

MS conditions

Values

Polarity

Negative

Capillary (kV)

3.0

Extractor (V)

1.0

R F lens (V)

1.0

Cone Voltage (V)

70

Source temperature (°C)

120

Desolvation temperature (°C)

300

Desolvation gas flow (L/h)

600

Cone gas flow (L/h)

60

MS range (m/z)

30–100

Analyte

Molecular formula

Precursor ion

Cone voltage

Dwell time

Sulfite

SO32-

80.1

68 V

0.02 s

(A) The UPLC chromatogram of sulfite (5 µg/mL), (B) corresponding SIR spectra and (C) chromatogram of sulfite (blank sample, Milli-Q water).

3.2 Performance analysis of UPLC-MS

The performance of the UPLC-MS method for sulfite ion analysis was validated on the basis of linearity, LOD, LOQ, reproducibility and repeatability.

3.3 Linearity and calibration range

Calibration standards of sulfite ion at concentration levels of 0.05, 0.10, 10, 40, 80 and 100 μg/mL. A linear relationship of the proposed analytical model was obtained using standard assay conditions by studying the chromatographic signal as a function of the selected sulfite ion concentrations. A set of six concentration levels were used to plot the calibration graph against their peak area and they were found to be linear over the higher concentrations (r2 > 0.999).

3.4 Quantification and detection limit

The LOD with signal to noise ratio of 3:1 and LOQ (corresponding to a signal to noise ratio of 10:1) values of the proposed UPLC-MS technique was calculated by injecting three replicates of blank samples (Milli-Q water) fortified with low amount of sulfite ion (Khan et al., 2013). The LOD for the sulfite ion was 0.003 μg/mL while the LOQ was determined as 0.01 μg/mL (Table 3). The values indicate that the suggested model is highly sensitive and is used for the analysis of the ions as well.

Anion

Linear range (μg/mL)

Correlation coefficient (r2)

LOD (μg/mL)

LOQ (μg/mL)

Precision (%RSD)

Intra-day

Inter-day

Sulfite

0.05–100

0.999

0.003

0.01

2.25

3.49

3.5 Accuracy and precision

The proposed method was established on the basis of reproducibility, repeatability, intra and inter precision assessment. In intra-day precision method analysis, standard was injected at 1 μg/mL concentrations and eighteen replicates were injected for the analysis of inter-day (Wabaidur et al., 2013). The excellent inter-day and intra-day precision values were achieved with < 3.5% (%RSD) was obtained (Table 3). The obtained values for and inter-day precision were relatively small and this revealed the application of UPLC-MS method for sulfite analysis.

3.6 Application of the method

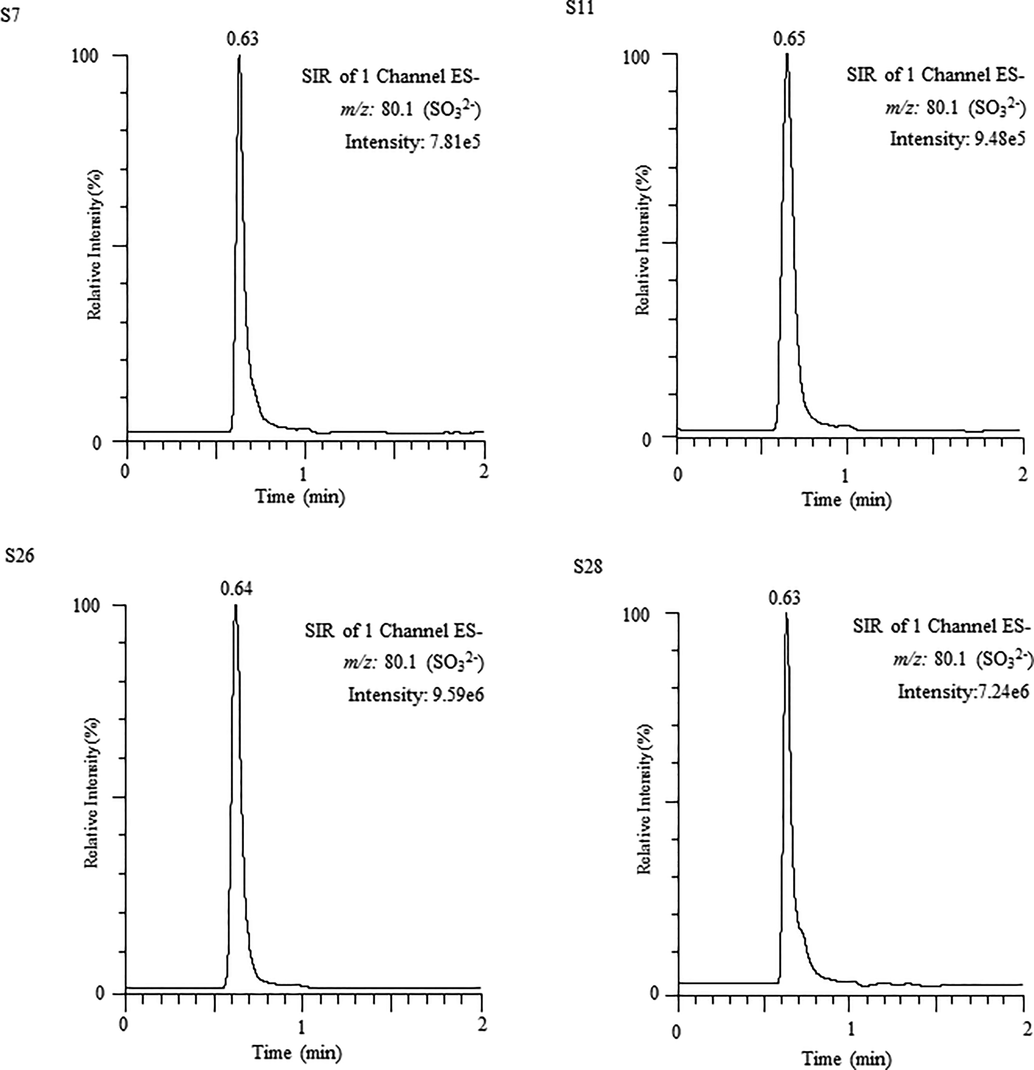

The validated UPLC–MS model was used for the quantification of sulfite ion present in many bottled and metropolitan water samples. The findings for the sulfite ion found in the analyzed water samples are listed in Table 4. It is obvious from the obtained results, that in all the analyzed water samples the sulfite ion were detected with high quantity. Among drinking water samples, the highest concentration of sulfite ion was found in sample 22 (65.79 μg/mL), while the sulfite ion contents in sample 26 of metropolitan water was found to be maximum 90.11 µg/mL. On the other hand, the lowest amount of sulfite ion was found in sample 1 (2.21 μg/mL) and in samples 7, 10 and 20 the sulfite ion quantity also found below the toxic level of 10 μg/mL. As an example, the UPLC–MS chromatogram of samples 7, 11, 26 and 28 are illustrated in Fig. 3. Analysis was performed to find the reproducibility and applicability of the proposed method. For this, 10 μg/mL standard solution of target analyte was added to each analyzed water samples and the % recovery was found in the range of 97.55–104.49% (Table 4). The drinking water is be worthy of additional worries, as it is widely consumed in our daily life. Table 5 illustrates the comparison of studied sulfite in water samples from Saudi Arabia with formerly stated data. The value of LOD in the current study vs. values achieved by means of conventional methods were considerably increased. The benefits of applying new UPLC-MS method in competition with other techniques are smaller analysis time (<1 min), tremendous accuracy and higher recovery values. Nonetheless, the sulfite was still detected in drinking water samples from Saudi Arabia. Hence, the detecting and decreasing the level of sulfite in water samples needed further apprehensions to meet better needs of strategies for consumer health. *Sample injected after filtration; -not described.

Water

Samples

SO32− (μg/mL)

SO32− added (μg/mL)

SO32− founda (μg/mL)

Recovery (%)

Bottled water

Sample 1

2.21

10

12.04

98.61

Sample 2

25.91

10

35.03

97.55

Sample 3

23.97

10

34.82

102.50

Sample 4

32.36

10

43.62

102.97

Sample 5

15.45

10

24.94

98.00

Sample 6

27.57

10

38.19

101.65

Sample 7

6.12

10

15.80

98.01

Sample 8

13.96

10

23.55

98.29

Sample 9

50.49

10

59.33

98.08

Sample 10

3.29

10

12.98

97.67

Sample 11

11.11

10

21.70

102.79

Sample 12

24.32

10

34.90

101.69

Sample 13

23.31

10

23.08

99.31

Sample 14

19.23

10

30.10

102.98

Sample 15

19.83

10

30.44

102.04

Sample 16

16.35

10

25.88

98.22

Sample 17

45.00

10

56.77

103.22

Sample 18

12.50

10

22.80

101.33

Sample 19

14.18

10

25.08

103.72

Sample 20

5.87

10

15.95

100.50

Sample 21

11.16

10

20.88

98.68

Sample 22

65.79

10

77.33

102.03

Metropolitan water

Sample 23

80.45

10

91.76

101.45

Sample 24

72.86

10

84.05

101.44

Sample 25

58.33

10

67.89

99.36

Sample 26

90.11

10

104.6

104.49

Sample 27

55.92

10

64.89

98.44

Sample 28

85.33

10

97.46

102.23

UPLC–MS chromatograms of sulfite obtained from water samples (S7, S11, S26 and S28).

Determination method

Extraction method*

Sampletreatment time (min)

Analysis time (min)

Sulfite (µg/mL)

RSD (%)

Recovery (%)

LOD (µg/mL)

References

UPLC-MS

Direct analysis

–

<1

2.21–90.11

<3.5

97.55–104.49

0.003

Current study

HPLC

Direct analysis

30

7.52

9.76

19.9

98.4

1.5

Zuo and Chen (2003)

Spectrophotometer

Direct analysis

–

–

2.6–8.0

13.2

101

0.01

James et al. (1984)

Flow injection analysis

Direct analysis

–

–

0.10

1.02–1.65

93.5–103.9

0.008–1.60

Yin et al. (2010)

4 Conclusions

A sensitive, fast and highly efficient UPLC-MS based analytical method was developed for the separation and detection of sulfite ion in bottled and metropolitan water. Among drinking water samples, the highest concentration of sulfite ion was found in sample 22 (65.79 μg/mL), while the sulfite ion contents in sample 26 of metropolitan water was found to be maximum 90.11 µg/mL. However, the lowest amount of sulfite ion was found below the toxic level of 10 µg/mL in sample 1 (2.21 μg/mL) 7, 10 and 20. The obtained results indicate that all the water samples contains sulfite ion and that can cause serious human health. The proposed UPLC-MS techniques is possessed many advantages compared to other conventional methods, in terms of no sample pretreatment required, very less analysis time and higher sensitivity. In addition, the mass spectrometric analysis with triple quadruple analyzer was allowed the acquisition of target analysis in SIR monitoring mode that provides a reliable confirmation of the compounds during the analysis. All the obtained validation parameters proves the usefulness of the method, the low value of the LOD proves the applicability of the method in other matrices where low amount of the sulfite ion is present.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through the Research Group No. RG-1437-004.

References

- Electrochemical determination of sulfite and phenol using a carbon paste electrode modified with ionic liquids and graphene nanosheets: application to determination of sulfite and phenol in real samples. Measurement. 2014;56:170-177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steric hindrance-enforced distortion as a general strategy for the design of fluorescence turn-on cyanide probes. Chem. Commun.. 2013;49:10136-10138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid dephosphorylation of glyphosate by Cu-catalyzed sulfite oxidation involving sulfate and hydroxyl radicals. Environ. Chem. Lett.. 2018;16:1507-1511.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient metoprolol degradation by heterogeneous copper ferrite/sulfite reaction. Environ. Chem. Lett.. 2018;16:599-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced degradation of Orange II using a novel UV/persulfate/sulfite system. Environ. Chem. Lett.. 2019;17:1435-1439.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of flow injection analysis for determining sulphites in food and beverages: a review. Food Chem.. 2009;112:487-493.

- [Google Scholar]

- Capillary electrophoretic determination of thiosulfate, sulfide and sulfite using in-capillary derivatization with iodine. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:2439-2444.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the formation and stability of hydroxyalkylsulfonic acids in wines. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2007;55:8670-8680.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fluorescent and colorimetric ion probes based on conjugated oligopyrroles. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2015;44:1101-1112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of ion chemosensors based on porphyrin analogues. Chem. Rev.. 2017;117:2203-2256.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reinvestigating the role of reactive species in the oxidation of organic co-contaminants during Cr(VI) reactions with sulfite. Chemosphere. 2018;196:593-597.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flow injection spectrophotometric determination of sulfite using a crude extract of sweet potato root (lpomoeabatatas (L.) Lam.) as a source of polyphenol oxidase. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1997;354:51-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel spectrophotometric method for batch and flow injection determination of sulfite in beverages. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2006;570:232-239.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorptive removal of sulfate from acid mine drainage by polypyrrole modified activated carbons: Effects of polypyrrole deposition protocols and activated carbon source. Chemosphere. 2017;184:429-437.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of zinc-aluminium layered double hydroxides for adsorptive removal of phosphate and sulfate: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic. Chemosphere. 2018;209:470-479.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of SO2 on respiratory system of adult Miyakejima resident 2 years after returning to the island. J. Occup. Health. 2009;51:38-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioelectrochemical approaches for removal of sulfate, hydrocarbon and salinity from produced water. Chemosphere. 2017;166:96-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- A low level spectrophotometric method for the determination of sulfite in water. Water Res.. 1984;18:751-753.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of aflatoxins in nonalcoholic beer using liquid−liquid extraction and ultra-performance LC−MS/MS. J. Sep. Sci.. 2013;36:572-577.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of total sulfite in wine by ion chromatography after in-sample oxidation. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2010;58:9463-9467.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contribution of dissolved sulfates and sulfites in hydrogen sulfide emission from stagnant water bodies in Sri Lanka. Chemosphere. 2003;52:901-907.

- [Google Scholar]

- Food safety risk assessment for estimating dietary intake of sulfites in the Taiwanese population. Toxicol. Rep.. 2016;3:544-551.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sulfite analysis of fruits and vegetables by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with ultraviolet spectrophotometric detection. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2003;51:1513-1517.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA damaging effects of sulfur dioxide derivatives in cells from various organs of mice. Mutagenesis. 2004;19:465-468.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of Cr(VI) from aqueous solutions by Na2SO3/FeSO4 combined with peanut straw biochar. Chemosphere. 2014;101:71-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of sulfite with emphasis on biosensing methods:a review. Anal. Biochem.. 2013;405:3049-3062.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sulfite-mediated oxidation of myeloperoxidase to a free radical: immuno-spin trapping detection in human neutrophils. Free Radic. Biol. Med.. 2013;60:98-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of a monolithic column to improve the simultaneous determination of four cephalosporin antibiotics in pharmaceuticals and body fluids by HPLC after solid phase extraction—a comparison with a conventional reversed-phase silica-based column. J. Chromatogr. B. 2004;809:175-182.

- [Google Scholar]

- SO2 inhalation contributes to the development and progression of ischemic stroke in the brain. Toxicol. Sci.. 2010;114:226-236.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pervaporation flow injection analysis for the determination of sulphite in food samples utilizing potassium permanganate-rhodamine B chemiluminescence detection. Food Chem.. 2010;212:893-898.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multisyringe flow system: determination of sulfur dioxide in wines. Analyst. 2000;125:1501-1505.

- [Google Scholar]

- A fast and sensitive HPLC method for sulfite analysis in food based on a plant sulfite oxidase biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2010;26:175-181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Food Labeling: Declaration of Sulfiting Agents. Fed Registry. 1986;51(131):25012-25020.

- [Google Scholar]

- A rapid method for the simultaneous determination of L-ascorbic acid and acetylsalicylic acid in aspirin C effervescent tablet by ultra performance liquid chromatography−tandem mass spectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2013;108:20-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flow injection chemiluminescence determination of loxoprofen and naproxen with the acidic permanganate-sulfite system. J. Pharma. Anal.. 2011;54:51-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- A turn-on fluorescent sensor for methylglyoxal. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2013;135:12429-12433.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of sulphur dioxide in solutions by pyridinium bromide perbromide and titrimetric and flow injection procedures. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1981;123:351-354.

- [Google Scholar]

- Practical aspects of fast HPLC separations for pharmaceutical process development using monolithic columns. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2004;523:149-156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selective sensitive and reversible turn-on fluorescent cyanide probes based on 2,2’-dipyridylaminoanthracene-Cu2+ ensembles. Chem. Commun.. 2012;48:11513-11515.

- [Google Scholar]

- Macrocycle contraction and expansion of a dihydrosapphyrin isomer. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2013;135:19119-19122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel spectrofluorimetric method for the determination of sulfite with rhodamine B hydrazide in a micellar medium. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2002;456:121-128.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of trace sulfite by direct and indirect methods using differential pulse polarography. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2007;603:30-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of sulfite in water samples by flow injection analysis with fluorescence detection. Chin. Chem. Lett.. 2010;21:1457-1461.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced abatement of organic contaminants by zero-valent copper and sulfite. Environ. Chem. Lett.. 2020;18:237-241.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simultaneous determination of sulfite, sulfate, and hydroxymethanesulfonate in atmospheric waters by ion-pair HPLC technique. Talanta. 2003;59:875-881.

- [Google Scholar]