Translate this page into:

Aseismic and seismic impact on development of soft-sediment deformation structures in deep-marine sand-shaly Crocker fan in Sabah, NW Borneo

⁎Corresponding authors at: Department of Geosciences, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar, 32610 Perak, Malaysia. jamil287@gmail.com (Muhammad Jamil), numair.siddiqui@utp.edu.my (Numair Ahmed Siddiqui)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

Soft-sediment deformation structures are present within the deep-marine fan of the West Crocker Formation, Sabah Basin, NW Borneo. Focus of this study is to highlight the impact of seismic and aseismic activities on the development of these structures and their distribution in deep-marine fan. Twenty-nine types of deformation structures were identified during the study of twelve exposed sections. These structures were grouped into five categories: i) water-escape structures, ii) sole marks, iii) clastic intrusions, iv) deformed laminations, and v) syn-depositional brittle and ductile deformation structures. The sediment deformation is interpreted to be caused either by aseismic processes like slope failure, gravity collapse, sediment overloading, density gradient, seismic induced mechanisms such as earthquakes, tectonic uplift, or combined effect of seismic and aseismic events. These structures are classified based on type of features developed during semi-consolidated phase of rock deposition. The seismite structures i.e., clastic intrusions, deformed laminations, and syn-depositional structures are correlated with active collisional tectonics during the Late Paleogene times in the Sabah Basin. In the present work, a generalized conceptual model has also been proposed for the development of soft-sediment deformation structures in a submarine fan environment. Dewatering structurers and rapid sedimentation features are associated with inner fan, load and flame structures are present within middle fan, while contorted layers, slumps and mass-transport deposits are linked with distal fan settings.

Keywords

Soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDSs)

Deep-marine sand-shaly fan

Seismites

West Crocker Formation

Sabah Basin

NW Borneo

1 Introduction

Genetic mechanisms and morphological characterization of sedimentary structures are vital for understanding of geological history and depositional processes active in a sedimentary basin (Liu et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2020). In siliciclastic rocks, soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDSs) are developed during or earlier phase of rock deposition, mostly in semi-consolidated phase of sediments prior to diagenesis. This deformation is also termed as penecontemporaneous or pre-lithification deformation (Owen et al., 2011). Fluidization and liquefaction phenomena contribute significantly to the development of SSDSs. However, a clear understanding, exact origin, and timing of development of sediment deformation structures are still ambiguous (Al-Mufti and Arnott, 2020).

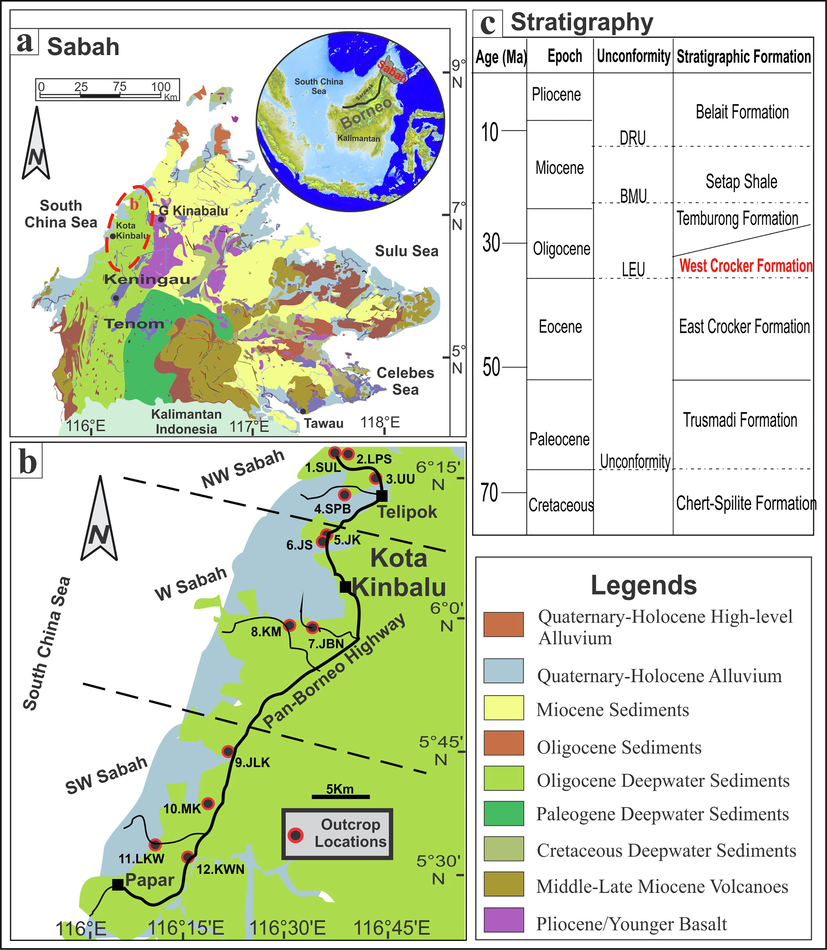

Various geological events like tsunamis, storm waves, and earthquakes (Moretti and Sabato, 2007) are responsible for the development of SSDSs. The factors that determine the development of soft-sedimentary structures are consolidation, saturation level, type of lithology, depth of sediment accumulation, intensity and epicenter of earthquakes (Liu et al., 2016). These SSDSs are also termed as seismites when triggered by the seismic activity (Singh and Jain, 2007). By using the deep-marine Crocker Formation of Sabah Basin as a case study (Fig. 1a,b), this research aims to characterize the occurrence of SSDSs, their spatial distribution in various architectural elements of a submarine fan, and relationship of seismites with collisional tectonic regime of the Sabah Basin during the Late Paleogene times.

Location of study area. a) regional map of NW Borneo with encircled Sabah area. b) location of twelve outcrops 1 to 4 in NW Sabah, locations 5–8 in West Sabah and 9–12 in SW Sabah. c) stratigraphy of the West Sabah.

2 Geological background

Deep-marine sediments of the Late Paleogene age are extensively outcropped in the West Sabah which are generally termed as Crocker sands because of dominant sandstone lithology (Jackson et al., 2009; Zakaria et al., 2013; Sheikh et al., 2021). The younger sediments are termed as Late Paleogene Crocker sediments to differentiate them from Early Paleogene Rajang Group (comprising of Trusmadi and East Crocker formations (Fig. 1c) (Abdullah et al., 2017). Hence, the term West Crocker Formation is now restricted to only those Late Paleogene sediments which are bounded by unconformable stratigraphic surfaces (Jamil et al., 2019, 2020).

Regionally, Borneo has a complex history of sedimentation and tectonics that resulted in the development of massive accumulation of deep-marine sediments during the Early Cenozoic era. (Mathew et al., 2014; Siddiqui et al., 2019; Usman et al., 2020; Ahmed et al., 2021a, 2021b). Sabah Basin is located in northern part of the Borneo that lies at complex junction of the South China Sea in the West, Celeb Sea in the SE, and Sulu Sea in the NE (Siddiqui et al., 2017, 2020; Usman et al., 2021). Previously, few sedimentary structures like flute marks, cross-bedding, convolution, parallel laminations, sand injectites and dish structures had been reported in this formation (Jackson et al., 2009; Zakaria et al., 2013; Madon, 2020; Jamil et al., 2021).

3 Data and methods

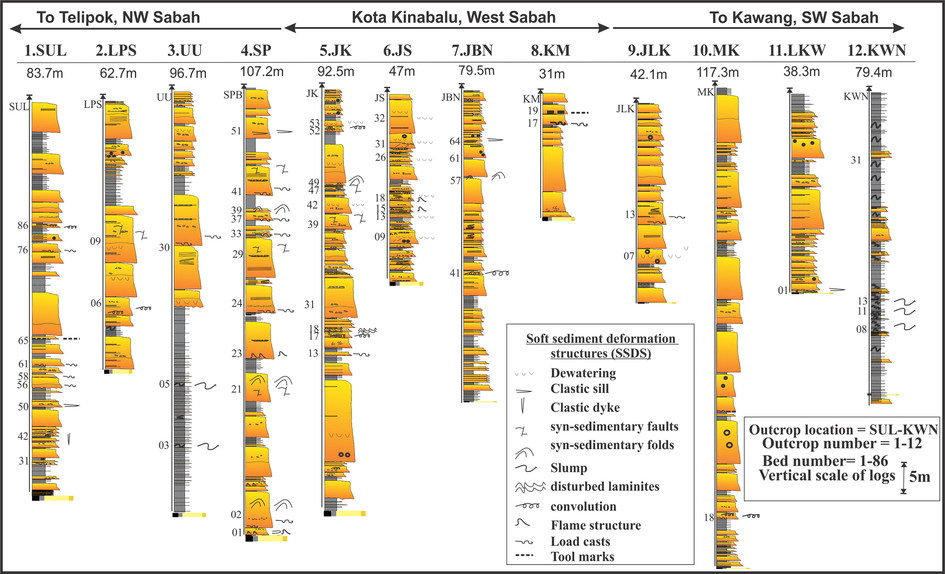

The geological field locations are mainly affected by compressional tectonic regime which is evident from vertically oriented stratigraphic sections. The transect selected for detailed sedimentary logging with deformation structures extends from NW Sabah (location 1: Jalan Sulaman near Telipok) to SW Sabah (location 12: Kawang) which is about 47.6 km in length along the Pan-Borneo Highway, Sabah (Fig. 2). Cumulative vertical thickness of all field logs for these exposed sections is about 877.40 m. Generally, this stratigraphic formation was deposited in deep-marine environment therefore most of the sandtone beds are structureless and do not bear any deformation structures. However, SSDSs were marked, located, and identified at several stratigraphic intervals in the geological field (Fig. 2). These sedimentary features were later interpreted in the light of previous literature to determine the geological processes active during the deposition in the respective sedimentary basin.

Distribution of SSDSs in twelve exposed sections, four from NW Sabah (1.SUL Jalan Sulaman section, 2.LPS Lapasan road section 3.UU University Utama section 4.SP Sepangger road section), four locations around Kota Kinabalu (5.JS Jalan UMS road section, 6.JK Jalan UMS behind KFC section, 7.JBN Jalan Bantayan section, 8.KM Kampung Madpai section), and four sections in SW Sabah (9.JLK Jalan Lok Kawi section, 10.MK Kampung Mook section, 11.LKW Lok Kawi wildlife road section 12.KWN Kawang section).

4 Results and interpretation

Twenty-nine types of SSDSs were identified which were broadly categorized into five major seismic and aseismic deformation structures in a deep-marine environment (Table 1). The sedimentary structures discussed in this study were identified at several stratigraphic levels within the West Crocker Formation. These features are classified based on geological processes responsible for the development of deformation structures including dewatering, overloading, intrusion, syn-depositional brittle, and ductile deformation structures.

No.

Types of SSDSs

Description

Type of groups

Figure

Processes

Mechanisms

1

Dish structures

Dewatering structures

3a, 3b

abrupt overpressure

Seismic or rapid sedimentation

2

Water-escape cusp

3c

flow pathways in fluidized sediments

Influence of pore pressure

3

Developed mud flames

Sole marks and flame structures

3d-3g

shale penetrates sand base

Reverse density gradient or seismic shock

4

Slight flame strcuture

3h

density contrast allows mud to move upward

Compensate sand pressure on mud

5

Load casts

4a

uneven loading

Gravitational instabilities, seismic origin

6

Pseudonodule

4b

heavier material sinks into mud

Sediment loading

7

Flute casts

4c

density loading

Erosional currents

8

Tool marks

4d

sagging, sand over mud drag

Density gradient

9

Detach sandnodule

4e

uneven loading

Dense sand nodules sink into mud

10

Ball and pillow

4f

disturbed sand base moves down into mud

Reverse density gradient, seismic activity

11

Sill ± faults

Clastic intrusions

5a-c, 5e

intrusion and displacement

Seismic or tectonics

12

Mud sill with dyke

5d

intrusion with variable stress directions

Co-seismic liquefaction

13

Minor mud dykes

5f

upward bedding of mud layer

Co-seismic liquefaction

14

Large mud dykes

5g

vertical injections

Seismic activity

15

Overturned convolution

Defromed laminations

6a

deformed laminae with broad hinge

Overloading or rapid sedimentation

16

Multiple convolution

6b, 6c

amalgamated sand overlain small structures

Differential liquefaction

17

Chaotic convolution

6d

convolution associated with silt unit

Gravitational movement

18

Convolution with mud

6e

crumpling of silty laminations

Differential liquefaction

19

Multiple laminites

6f

lamiantions are slightly bended

Ductile laminae deformation

20

Disturbed laminites

6g

small-scale overloading

Injection with slight bending

21

Multiple syn-sedimentary faults

Syn-depositional structural deformation

7a, 7b

array of faults due to continuous stress

Tectonic or seismic shocks

22

Syn-sedimentary fault

7c, 7d

localized stress

Seismic event or other short-lived mechanism

23

Syn-sedimentary fold

7e

ductile deformation phase

Compressional phenomenon

24

Syn-sedimentray fault and fold

7f, 7g

brittle and ductile deformation

Differential stress behaviour

25

Syn-sedimentary Fault propagation fold

7h

initially folding and later faulting

Convergent tectonic mechanism

26

Contorted layers

8a, 8d

individual lamina differentially deform

Seismic episodes

27

Chaotic slumping

8b, 8c

deformed Silty mud incorporate into sand

Minor chaotic event

28

Slump with sand clasts

8e, 8f

rotational component in chaos

Gravitational collapse

29

Mass-transport complex

8g, 8h

complex orientation of lithology

Slope failure, gravitational collapse

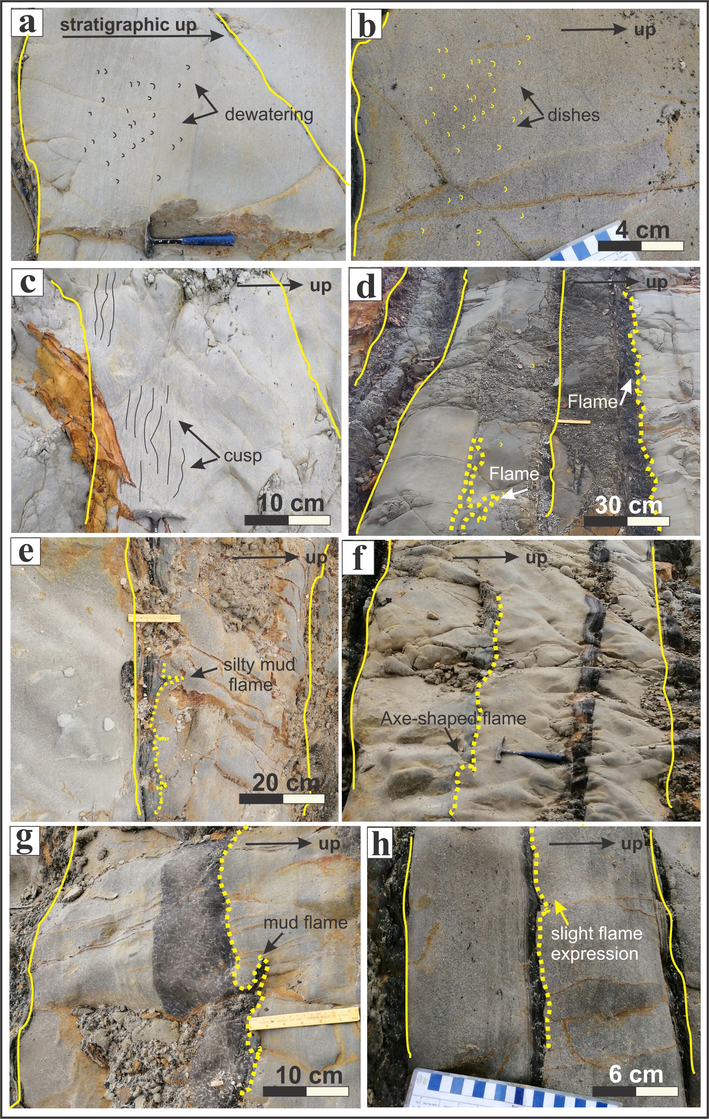

4.1 Water-escape structures

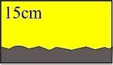

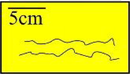

4.1.1 Dish structures

Small saucers (dishes), which are sometimes separated by vertical columns, represent the escape of pore-water in an upward direction during lithification of sediments. The size of dishes vary from 1 to 3 cm and morphology is mainly concave up structures in an undulated linear fashion. These structures are rare in NW and SW Sabah, but they are abundant in the West Sabah. The sandstone units in the West Sabah are relatively clean therefore, these structures are faint. Generally, the dewatering structures are common in thick to massive muddy sandstones (Fig. 3a). Few examples of dish structures have also been identified at Jalan UMS behind KFC (JK) section, West Sabah (Fig. 3b), which are interpreted to be deformed by earthquakes (Zeng et al., 2018).

Dewatering and flame structures a) dewatering columns in massive sandstone. b) dish structures in sandstone with mud laminae. c) water-escape cusp in massive sandstone. d) developed flame structure at the base of overlying sand beds. e) silty mud flame developed in between sand bed. f) axe-shaped flame structure bounded by two sandstone intervals. g) wedge-shaped flame structure developed by underlying mud unit. h) slight effect of flame by thin mud unit into overlying sand bed.

4.1.2 Water-escape cusp

Cusp mainly occur in between two coarsening up sandstone units when the sediments are still in phase of fluidization (Owen, 1996). They are columnar generally vertical and similar in shape like the flame structure (Ali and Ahmad Ali, 2018). The zone of cusp structures ranges from 4 to 7 cm and width from 1 to 11 cm (Fig. 3c). These cusp structures are relatively less common as compared to traditional dish structures in the study area. In general, the seismic impact or abrupt overpressure resulted in the movement of water from unlithified sediments and consequently develops water-escape structures (Owen, 1996).

4.2 Sole marks

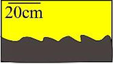

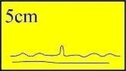

4.2.1 Flame structures

Flame structures are usually developed in shaly unit overlying sandstone, or in muddy sandstone overlying clean sandstone unit. The mud flames are equally developed in shale laminae (Fig. 3d) bounded by sandstone intervals. However, the morphology of flame is like mud injection in rare cases (Fig. 3e), axe-shaped (Fig. 3f) or linear wedge structure (Fig. 3g). Sometimes the flame structure is less developed due to very thin mud lamina and is termed as slight flame expression (Fig. 3h). The flame dimensions vary in size from less than 1 cm (Fig. 3h) to more 5 cm in flame height (Fig. 3g). The triggering process for development of flame include gravity loading (Ge and Zhong, 2018), or seismic shear (Zeng et al., 2018).

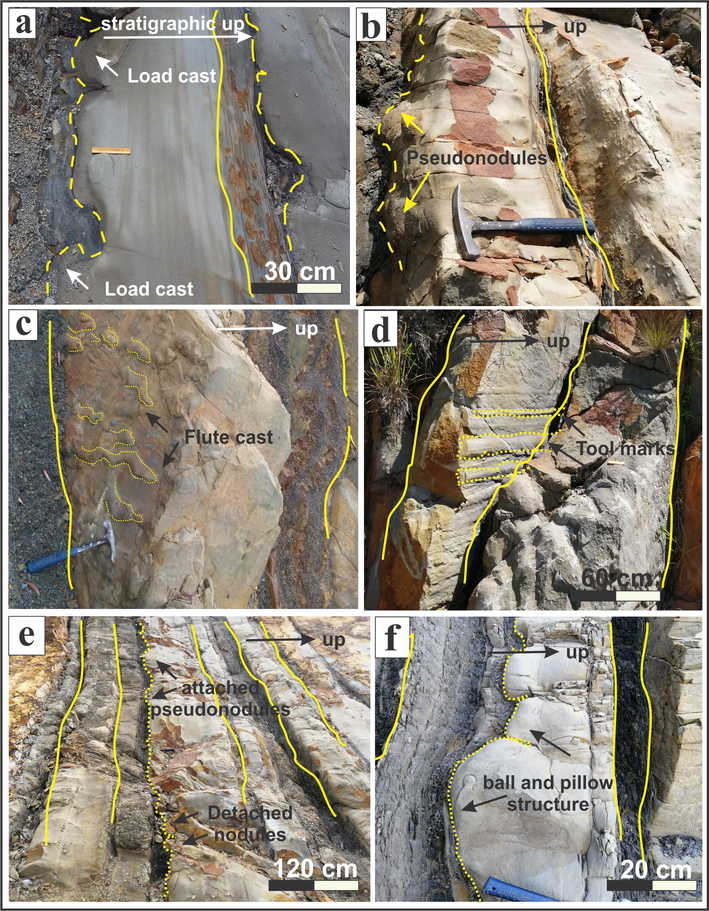

4.2.2 Load structures

Deep-marine deposits with alternate sand-shale lithology (competence contrast) are often characterized by load structures. The range of deformation varies significantly where lateral continuity of these load structures is limited, and they are developed in form of symmetrical spheres as well as asymmetrical geometries (Fig. 4a, 4b). Brief expressions of flute casts (Fig. 4c) and tool marks (Fig. 4d) are present in the West Sabah interpreting the deformation associated with drag movement of sediments during the high-density cohesive gravity flow (Peakall et al., 2020).

Sole marks and load structures. a) load casts at the base of sandstone unit. b) Pseudonodules developed due to sediment loading. c) flute casts representing the effect of erosional currents. d) tool marks at the base of sandstone. e) undulated sandstone base and detached nodules due to sinking of dense sandstone into underlying shale unit. f) ball and pillow structure formed at base of sandstone.

4.2.3 Pseudonodules

Variable shapes and morphologies of detached and isolated nodules are entrenched in an underlying lithology (Fig. 4e) having density contrast are termed as pseudonodules (Ali and Ahmad Ali, 2018). The diameter of irregular spheroidal morphologies varies from 3 to 9 cm while the long axes vary from 8 to 14 cm and short axes from 4 to 9 cm. These pseudonodules are interpreted to be the result of sediment loading of more dense sand in underlying shale interval (Rodrı́guez-Pascua et al., 2000).

4.2.4 Ball and pillow structures

The sandstone layer is divided into many concentric pillows which are nearly spherical or ellipsoidal. These individual plano-convex pillow shapes can either be isolated masses or partially connected (McLaughlin and Brett, 2004). The diameter of pillows varies from 8 to 23 cm, while the ball diameter ranges only from 4 to 11 cm (Fig. 4f). Ball and pillow structures are formed by reverse density gradient as well as seismic impact on semi-consolidated sediments (Obermeier, 1996).

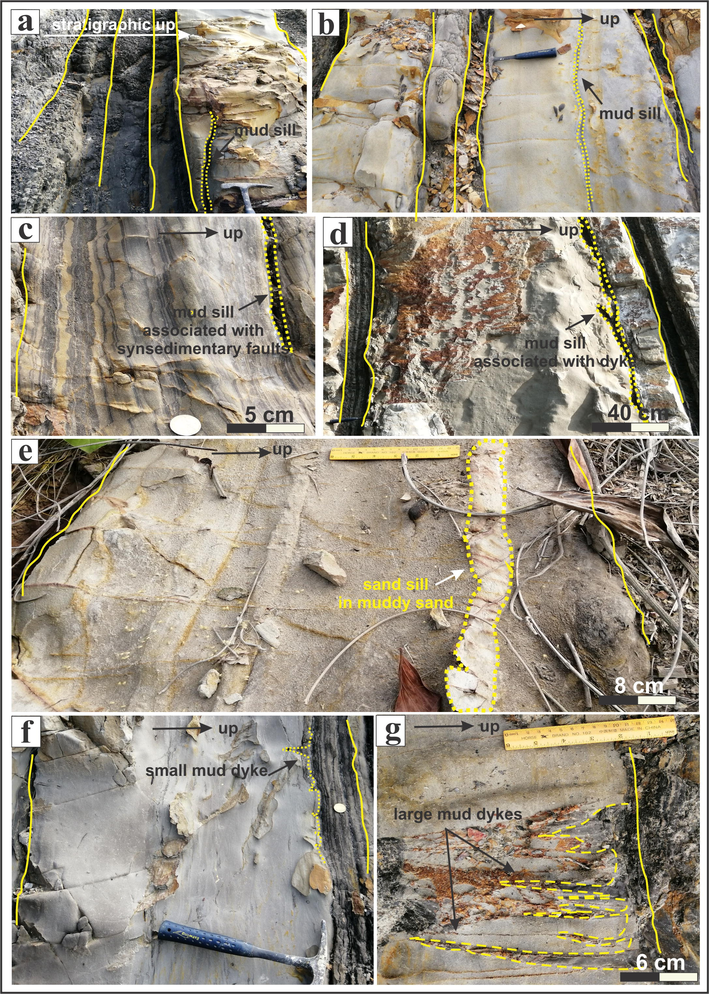

4.3 Soft-sediment intrusions

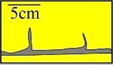

4.3.1 Clastic sills

Bedding parallel mud intrusions are present in various forms where the width of mud sill is less than 1 cm, but the length is more than 40 cm (Fig. 5a, b). Clastic sills are associated with syn-depositional faulting (Fig. 5c) are less common in depositional record. These mud sills are rarely associated with mud dykes (dyke off-shoots from the parent sill structure) as in the Jalan Bantayan site, West Sabah (Fig. 5d). In some cases, clean sand sill is intruded into the muddy sand unit (Fig. 5e). Due to limited lateral continuity, these clastic sills are interpreted to be developed by seismic triggering mechanism (Madon, 2020).

Injection or intrusion structures. a) discontinuing mud sill penetrated sandstone unit. b) mud sill into thick sandstone interval. c) mud sill intruded into syn-depositional faulted sandstone. d) sill associated dyke structure in sandstone unit. e) clean sand sill injected into muddy sandstone. f) small mud dykes injected into underlying sandstone interval. g) large mud dykes intruded in sandstone at multiple points.

4.3.2 Clastic dykes

Sand or mud filled linear features, that cut across the adjacent layers vertically or at an angle, have size from centimeters to meter scale (Kumar et al., 2020). In the studied sections, clastic dykes are mainly intruded vertically into older strata with length of about 2–5 cm (Fig. 5f). These mud dykes are often injected vertically into medium to thick bedded sandstone unit with variable width from 0.8 cm to 2.3 cm at multiple points and length of dykes may exceeds 20 cm (Fig. 5g). The existence of dykes in the studied area indicate the impact of paleo-seismic activity in form of moderate to high magnitude earthquakes (Rodrı́guez-Pascua et al., 2000).

4.4 Defromed lamination strcutures

4.4.1 Convolute laminations

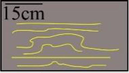

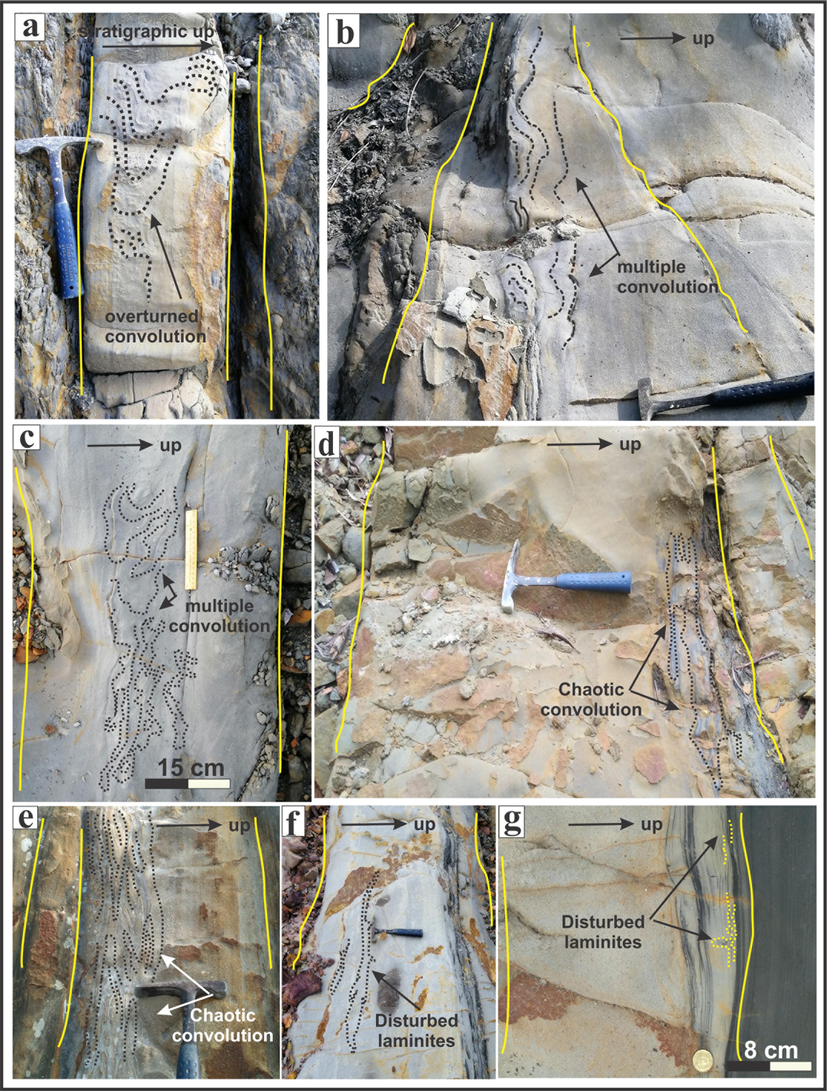

Complex folding and crumpling of laminations in a sedimentary unit is termed as convolution (Kumar et al., 2020). Overturned convolute laminations are present with broad hinge area in Jalan Sulaman section, NW Sabah (Fig. 6a), while multiple convolutions are overlain by structureless massive sandstone unit in the Lapasan section, NW Sabah (Fig. 6b), and Jalan UMS roadside, West Sabah (Fig. 6c). In some cases, these convolute structures may develop a chaotic morphology in clean sandstone (Fig. 6d) as well as in form of silty mud laminations (Fig. 6e). The convolutions extend in length from 28 to 67 cm along the strike of bed and range in width from 6 to 21 cm. However, the intensity of deformation or folding varies significantly and depending on liquefaction (Koç-Taşgın and Altun, 2019).

Convolution and disturbed laminites. a) overturned convolution. b) and c) multiple convolutions. d) and e) chaotic convolution. f) multiple disturbed laminites associated with mudclasts. g) small-scale disturbed laminites overlain by mud cap.

4.4.2 Disturbed laminites

Disturbed laminites are often developed in silty sand units contain small-scale deformation which are expressed in multiple morphologies (Fig. 6f). The rock units containing these small-scale structures are massive sandstone having floating mudclasts (Fig. 6f) or sandstone gradually altered into disturbed laminations with mud cap (Fig. 6g). Furthermore, the scale of these structures ranges from 7 mm to 4 cm, interpreted as ductile deformation (Ali and Ahmad Ali, 2018).

4.5 Syn-depositional structural deformation

4.5.1 Syn-sedimentary faults

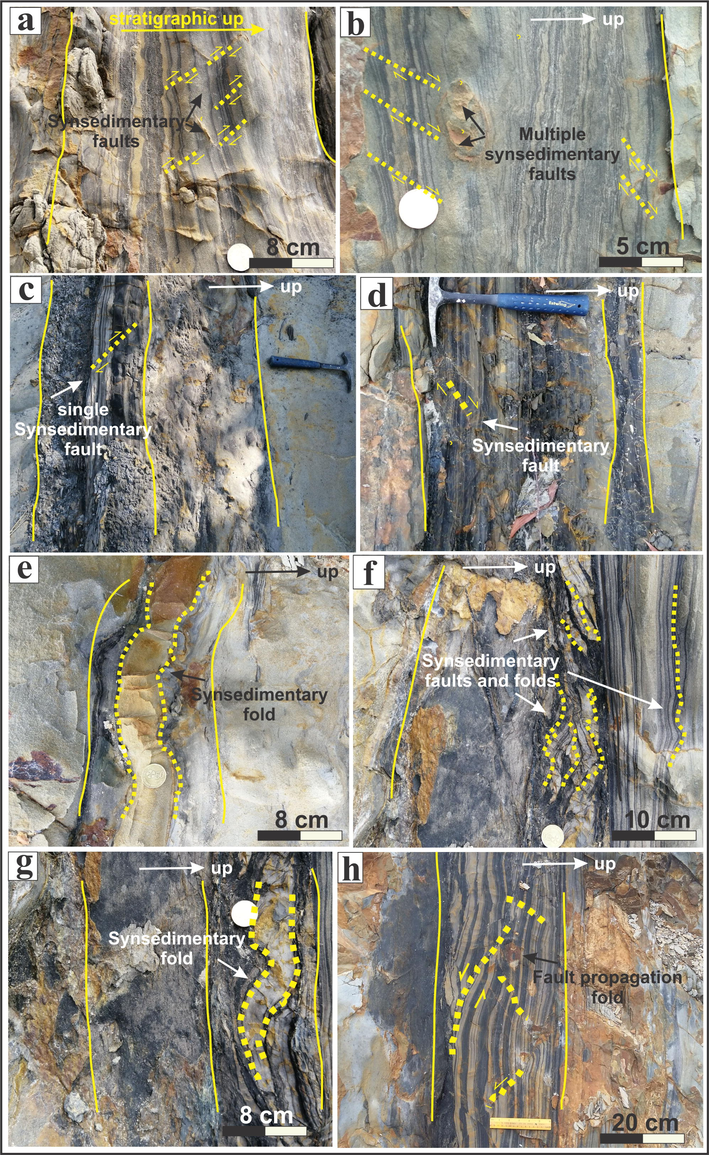

Brittle deformation structures like syn-sedimentary faults are common in heterolithic lithologies in the study area where displacement along the fault plane is normally less than cm scale and bounded by undeformed beds indicating syn-sedimentary origin (Fig. 7a). Most of these faults display reverse dip-slip movement that is associated with compressional stress (Fig. 7b). They are correlated with the subduction and collisional regime of the study area. However, normal syn-sedimentary faults are sporadically present in the studied sections (Fig. 7c,d) indicating a local extensional event (Ko et al., 2017).

Syn-depositional deformations. a) and b) multiple arrays of syn-sedimentary faults. c) and d) localized stress resulted into single syn-sedimentary fault. e) slight bending of thin sandstone. f) syn-depositional fault and folds overlain by undeformed laminations. g) syn-sedimentary folding in sandstone interval. h) fault propagation fold representing a combined effect of brittle and ductile deformations.

4.5.2 Syn-sedimentary folds

Syn-sedimentary folds having broad or narrow area of fold axis (Fig. 7e-g) are present in the Sepangger section, NW Sabah. These syn-sedimentary folds may also be associated with faults (Fig. 7h) as fault propagation folds. In contrast to syn-sedimentary faults, most of the syn-depositional folds are related to clean sandstone units (Fig. 7e), while few syn-sedimentary folds are linked with heterolithic beds (Fig. 7h). The underlying and overlying units are both undeformed that indicate seismic events responsible for these deformation structures (Marco and Agnon, 2005).

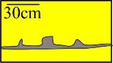

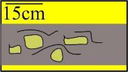

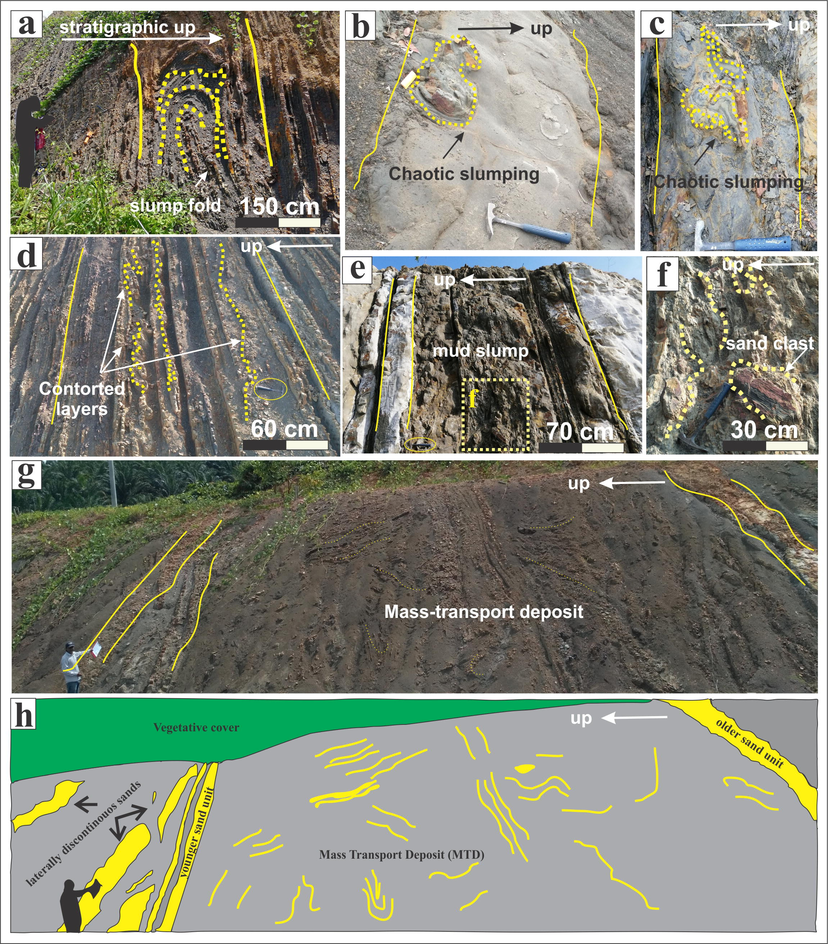

4.5.3 Slump structures and mass-transport deposits

Slump units are present in silty shale (Fig. 8a), in sandstone with silty lumps (Fig. 8b), and/or patches of muddy sandstone showing chaotic nature with some rotational activity and floating mudclasts (Fig. 8c). These minor slump units, with limited lateral continuity, are also termed as contorted layers having multiple small events of slumping (Fig. 8d). The small broken mud and sand fragments are common in slump beds bounded either by stratified bedding (Fig. 8e) with undulations or rough arrangement of sediments (Fig. 8f). The size of slump may vary from multimeter (Fig. 8a) to cm level (Fig. 8d) depending on the unit in which slumping took place during the phase of sediment consolidation.

Syn-depositional structural deformation. a) slump fold. b) and c) chaotic slumping. d) contorted layers. e) and f) sand clasts in mud slump. g) and h) mass-transport deposits in silty shale units.

However, presence of various unarranged and partially folded silty shale units (Fig. 8g) in the Kawang section in SW Sabah (Jamil et al., 2020) are interpreted as mass-transport deposits (Fig. 8h) as a result of gravity collapse (Alsop et al., 2019). Furthermore, the presence of repetitive horizons of contorted layers at various levels interpreted to be the result of aseismic trigger; i.e., slope failure (Owen et al., 2011).

5 Discussion

5.1 Seismic and aseismic impact

The Sabah Basin was tectonically active in the Late Paleogene times when subduction and collision of South China Sea was active beneath NW Borneo (Hennig-Breitfeld et al., 2019). The existence of sand dykes, mud flames, ball and pillow structures, and syn-sedimentary faults suggest moderate to high magnitude paleo-seismic activity in the area that was responsible for soft-sediment deformation. However, contorted layers and mass-transport deposits in NW Sabah indicate aseismic origin for the development of SSDSs (Alsop et al., 2019). Moreover, convolute laminations are often associated with thick to massive sandstone indicating the rapid sedimentation as a possible aseismic triggering mechanism (Koç-Taşgın and Altun, 2019). The small broken sand blocks in slump suggests the element of slide associated with slump structure due to liquefaction aseismic phenomenon.

However, slump structures could also slightly fold the silty sandstone thin beds and laminae which are not linked with slide event. They are potentially linked with seismic shocks in unconsolidated sediments (Singh and Jain, 2007). Furthermore, presence of syn-sedimentary faults in the Sepangger, NW Sabah because of localized forces also point out the seismic activity as a possible triggering mechanism (Tongkul, 2017). These sediments having preserved seismic record in form of deformation are termed as seismites that are quite common in active tectonic margins. Large-scale slump structure in deep-marine sediments (NW Sabah) are interpreted to be the result of earthquake of large magnitude (Bowman et al., 2004).

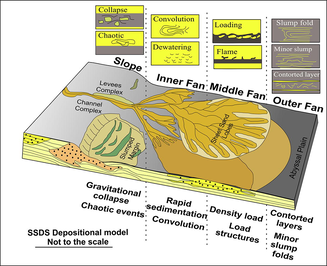

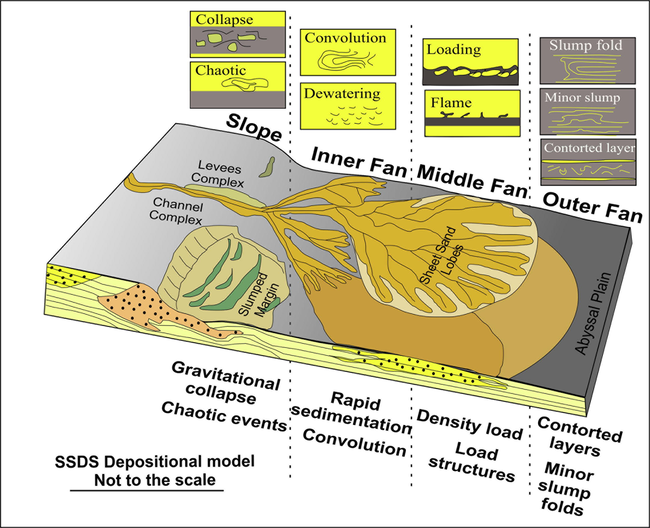

5.2 Distribution in deep-marine fan

The present study integrates the development and distribution of SSDSs with previously proposed generalized submarine fan models (Fig. 9). The previous literature elaborates the distribution of SSDSs in glacio-lacustrine settings (Pisarska-Jamroży and Woźniak, 2019). However, no such attempt has been made to correlate the occurrence of SSDSs and their distribution in deep-marine fan. Initially, facies and facies associations were interpreted for the studied sections and the individual deep-marine architectural elements were identified for entire Crocker submarine fan (Fig. 2). Later, various types of SSDSs were interpreted by their distribution a generalized submarine fan settings (DeVay et al., 2000). The gravitational collapse and chaotic structures found to be associated with slopes with broken sand clasts in siliciclastic rock successions. Rapid sedimentary influx resulted in massive sand units having floating mudclasts, convolution, and dewatering structures associated with proximal fan settings. Alternate medium to thin bedded sand-mud units with load structures are found to be associated with middle fan environment. Minor slump folds and contorted layers are mainly present in silty-shale intervals of outer fan deposits.

A conceptual depositional model proposed for the correlation of deep-marine fan with development of SSDSs.

6 Conclusion

The impact of numerous seismic and aseismic events resulted in the development of wide variety of SSDSs including water-escape structures, ball and pillow structures, pseudonodules, load structures, flame structures, intrusion structures and distorted laminations, and syn-depositional structures in a submarine fan. Load and flame structures were associated with upper denser interval above lighter lithology and caused deformation due to liquidization of unstable sediments. Uneven loading or density contrasts were linked with instabilities of gravity, whereas ascending eviction of pore fluids attributed to water-escape structures. Convolution and syn-sedimentary folds were associated with ductile deformation during downslope gravitation movement, while brittle actions contributed the development of syn-depositional faults. Gravity and seismic activity were major factors which develop the SSDSs in a sedimentary basin. Episodic appearance of syn-depositional folds and faults in stratigraphic intervals interpreted as seismites which are developed due to seismic events in active tectonic settings. Conclusively, these structures were developed in response to both seismic and aseismic processes that were active at discrete stratigraphic intervals in a deep-marine sedimentary basin. A generalized conceptual model is proposed in this study from inner to outer fan environment; where rapid sedimentation and convolution structures are present in inner fan, load structures in middle fan, and minor slump or contorted layers are confined to outer fan environment.

Funding

This project was supported by the Petroleum Research Fund (PRF Cost No. 0153AB-A33) awarded to Dr. Eswaran Padmanabhan and Fundamental Research Grant, Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) Malaysia (Project ID 16880, Reference Code FRGS/1/2019/STG09/UTP/03/1).

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere thanks to Shale Gas Research Group (SGRG) and Department of Geosciences, Univeristi Teknologi PETRONAS (UTP) Malaysia for fieldwork and data analysis. The comments and feedback from the reviewers greatly improved the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Hydrocarbon source potential of Eocene-Miocene sequence of Western Sabah, Malaysia. Mar. Pet. Geol.. 2017;83:345-361.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of hydrocarbon source rock potential: Deep marine shales of Belaga Formation of Late Cretaceous-Late Eocene, Sarawak, Malaysia. Journal of King Saud University - Science. 2021;33(1):101268.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Geochemistry of Eocene Bawang Member turbidites of the Belaga Formation. Borneo: Implications for provenance, palaeoweathering, and tectonic setting. Geological Journal. 2021;56(5):2477-2499.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The origin and significance of convolute lamination and pseudonodules in an ancient deep-marine turbidite system: From deposition to diagenesis. J. Sediment. Res.. 2020;90:480-493.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seismically induced soft-sediment deformation structures in an active seismogenic setting: The Plio-Pleistocene Karewa deposits, Kashmir Basin (NW Himalaya) J. Struct. Geol.. 2018;115:28-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying soft-sediment deformation in rocks. J. Struct. Geol.. 2019;125:248-255.

- [Google Scholar]

- Late-Pleistocene seismites from Lake Issyk-Kul, the Tien Shan range, Kyrghyzstan. Sed. Geol.. 2004;163(3-4):211-228.

- [Google Scholar]

- DeVay, J.C., Risch, D., Scott, E. and Thomas, C., 2000. A Mississippi-Sourced, Middle Miocene (M4), Fine-Grained Abyssal Plain Fan Complex, Northeastern Gulf of Mexico, AAPG Memoir 72/SEPM Special Publication, pp. 109-118.

- Soft-sediment deformation structures as indicators of tectono-volcanic activity during evolution of a lacustrine basin: A case study from the Upper Triassic Ordos Basin. China. Marine and Petroleum Geology. 2020;115:104250.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trigger recognition of Early Cretaceous soft-sediment deformation structures in a deep-water slope-failure system. Geol. J.. 2018;53(6):2633-2648.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new upper Paleogene to Neogene stratigraphy for Sarawak and Labuan in northwestern Borneo: Paleogeography of the eastern Sundaland margin. Earth Sci. Rev.. 2019;190:1-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sedimentology, stratigraphic occurrence and origin of linked debrites in the West Crocker Formation (Oligo-Miocene), Sabah, NW Borneo. Mar. Pet. Geol.. 2009;26(10):1957-1973.

- [Google Scholar]

- A contemporary review of sedimentological and stratigraphic framework of the Late Paleogene deep marine sedimentary successions of West Sabah, North-West Borneo. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Malaysia. 2020;69:53-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Deep marine Paleogene sedimentary sequence of West Sabah: contemporary opinions and ambiguities. Warta Geologi. 2019;45:198-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facies Heterogeneity and Lobe Facies Multiscale Analysis of Deep-Marine Sand-Shale Complexity in the West Crocker Formation of Sabah Basin, NW Borneo. Applied Sciences. 2021;11(12):5513.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Soft sediment deformation structures in a lacustrine sedimentary succession induced by volcano-tectonic activities: An example from the Cretaceous Beolgeumri Formation, Wido Volcanics, Korea. Sed. Geol.. 2017;358:197-209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Soft-sediment deformation: deep-water slope deposits of a back-arc basin (middle Eocene-Oligocene Kırkgeçit Formation, Elazığ Basin) Eastern Turkey. Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 2019;12(24)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Soft Sediment Deformation Structures in Quaternary Sediments from Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Western India. J. Geol. Soc. India. 2020;95(5):455-464.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seismically induced soft-sediment deformation structures in the Palaeogene deposits of the Liaodong Bay Depression in the Bohai Bay basin and their spatial stratigraphic distribution. Sed. Geol.. 2016;342:78-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sand injectites in the West Crocker Formation, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Malaysia. 2020;69:11-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-resolution stratigraphy reveals repeated earthquake faulting in the Masada Fault Zone, Dead Sea Transform. Tectonophysics. 2005;408(1-4):101-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- An evolutionary model of the near-shore Tinjar and Balingian Provinces, Sarawak, Malaysia. International Journal of Petroleum and Geoscience Engineering. 2014;2:81-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eustatic and tectonic control on the distribution of marine seismites: examples from the Upper Ordovician of Kentucky, USA. Sed. Geol.. 2004;168(3-4):165-192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recognition of trigger mechanisms for soft-sediment deformation in the Pleistocene lacustrine deposits of the SantʻArcangelo Basin (Southern Italy): Seismic shock vs. overloading. Sed. Geol.. 2007;196(1-4):31-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of liquefaction-induced features for paleoseismic analysis—an overview of how seismic liquefaction features can be distinguished from other features and how their regional distribution and properties of source sediment can be used to infer the location and strength of Holocene paleo-earthquakes. Eng. Geol.. 1996;44(1-4):1-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental soft-sediment deformation: structures formed by the liquefaction of unconsolidated sands and some ancient examples. Sedimentology. 1996;43(2):279-293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recognising triggers for soft-sediment deformation: Current understanding and future directions. Sed. Geol.. 2011;235(3-4):133-140.

- [Google Scholar]

- An integrated process-based model of flutes and tool marks in deep-water environments: Implications for palaeohydraulics, the Bouma sequence and hybrid event beds. Sedimentology. 2020;67(4):1601-1666.

- [Google Scholar]

- Debris flow and glacioisostatic-induced soft-sediment deformation structures in a Pleistocene glaciolacustrine fan: The southern Baltic Sea coast, Poland. Geomorphology. 2019;326:225-238.

- [Google Scholar]

- Soft-sediment deformation structures interpreted as seismites in lacustrine sediments of the Prebetic Zone, SE Spain, and their potential use as indicators of earthquake magnitudes during the Late Miocene. Sed. Geol.. 2000;135(1-4):117-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, N.A., Jamil, M., Ling Chuan Ching, D., Khan, I., Usman, M. and Sooppy Nisar, K., 2021. A generalized model for quantitative analysis of sediments loss: A Caputo time fractional model. J. King Saud Univ. – Sci. 33, 101179

- Sedimentological characterization, petrophysical properties and reservoir quality assessment of the onshore Sandakan Formation, Borneo. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng.. 2020;186:106771.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Generic hierarchy of sandstone facies quality and static connectivity: an example from the Middle-Late Miocene Miri Formation, Sarawak Basin. Borneo. Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 2017;10:237.

- [Google Scholar]

- High resolution facies architecture and digital outcrop modeling of the Sandakan formation sandstone reservoir, Borneo: Implications for reservoir characterization and flow simulation. Geosci. Front.. 2019;10(3):957-971.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liquefaction and fluidization of lacustrine deposits from Lahaul-Spiti and Ladakh Himalaya: Geological evidences of paleoseismicity along active fault zone. Sed. Geol.. 2007;196(1-4):47-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Active tectonics in Sabah–seismicity and active faults. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Malaysia. 2017;64:27-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Linking the influence of diagenetic properties and clay texture on reservoir quality in sandstones from NW Borneo. Mar. Pet. Geol.. 2020;120:104509.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Usman, M., Siddiqui, N.A., Zhang, S., Mathew, M., Jamil, M., Zhang, Y. and Ahmed, N., 2021. 3D Geo-Cellular Static Virtual Outcrop Model and its Implications for Reservoir Petro-Physical Characteristics and Heterogeneities. Petroleum Science, 18, in press.

- Sedimentary facies analysis and depositional model of the Palaeogene West Crocker submarine fan system, NW Borneo. J. Asian Earth Sci.. 2013;76:283-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bedding-parallel lenticular soft-sediment deformation structures: A type of seismite in extensional settings? Tectonophysics. 2018;747-748:128-145.

- [Google Scholar]