Translate this page into:

Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L.) and Cassia (Senna bicapsularis L.) flower extracts

*Corresponding author. Tel.: +60 4653 5212; fax: +60 4657 3678 rajeevbhat1304@gmail.com (Rajeev Bhat) rajeevbhat@usm.my (Rajeev Bhat)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Available online 20 December 2012

Abstract

Antioxidant activity, antibacterial properties, color and FT-IR spectral analysis of flowers belonging to hibiscus and Cassia species were investigated. Radical scavenging activity of sample extracts were determined based on the percent inhibition of DPPH and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays. Total phenolics were estimated based on the Folin–Ciocalteu method, while, vanillin–HCl and aluminum chloride methods were employed to estimate total tannins and flavonoids in the sample extracts, respectively. To determine total flavonols and anthocyanin contents, spectrophotometric method was employed. For antibacterial activities, modified agar disk diffusion method was adopted. Color analysis was performed using a colorimeter, while functional groups of compounds were identified using a FTIR-spectrophotometer. Results showed both the flower extracts to encompass high amount of antioxidant compounds and exhibit significant antioxidant activities, which depended on extraction solvents. Ethanolic extracts of Cassia had high total phenolic, total flavonoid and total flavonol content, and showed highest activity for inhibition of DPPH, while aqueous extract of hibiscus had high tannin and anthocyanin contents, and showed high ferric reducing antioxidant power. With regard to antimicrobial activity, aqueous and ethanolic extracts of hibiscus inhibited the growth of food-borne pathogens such as Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus, while in Cassia the growth of Bacillus cereus and Klebsiella pneumoniae was inhibited. Compared to Cassia, color analysis of hibiscus showed lower chroma and hue angle values. FTIR spectra of both flowers were comparable and showed the presence of polysaccharides, suberin and triglycerides. Our results indicate the potential of exploiting these two flowers as a source of natural food preservative or colorant, while developing novel functional foods.

Keywords

Flower extracts

Antioxidant activity

Antibacterial activity

FTIR analysis

Food preservative

1 Introduction

Recent years have witnessed enhanced research work reported on plants and plant products. In this regard, plants with traditional therapeutic usage are being screened more efficiently—to be considered as a substitution or as a better alternative for chemical based food preservatives. Additionally, plants can be an excellent source of natural antioxidants and can be effectively used in the food industry as a source of dietary supplements or as natural antioxidants to preserve the quality and improve the shelf-life of food products (Tiwari et al., 2009; Voon et al., 2012).

Traditionally, several plants and their products have been used in foods (as herbs or spices) as a mode of natural preservative, flavoring agent as well as a remedy to treat some of the common ailments in humans. This property of curing is attributed mainly to their antimicrobial activities. Use of natural plant derived antimicrobials can be highly effective in reducing the dependence on antibiotics, minimize the chances of antibiotic resistance in food borne pathogenic microorganisms as well as help in controlling cross-contaminations by food-borne pathogens (Voon et al., 2012). In addition to the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities exhibited by plants or their extracts, they can also be used as natural colorants of foodstuffs; as in most of the cases, they are believed to be safe, and non-toxic to humans (Rymbai et al., 2011; Boo et al., 2012; Gupta and Nair, 2012).

Of late, many reports are available wherein flowers or their extracts have been shown to exhibit rich antioxidant and antimicrobial properties (Shyu et al., 2009; Jo et al., 2012; Voon et al., 2012). Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. (family; Malvaceae) is a profusely flowering, perennial, woody ornamental shrub distributed widely in the tropical regions. Previous studies have indicated H. rosa-sinensis to possess bioactive properties and is recommended to be used as an herbal alternative to cure many diseases (Obi et al., 1998). On the other hand, Cassia bicapsularis L. (or Senna bicapsularis L.) (family; Fabaceae) is one of the common flowering, ornamental plant belonging to Cassia species which is widely distributed in South American and tropical countries. Traditionally, plants belonging to Cassia species are believed to possess medicinal values.

Based on this, the present study was aimed at evaluating the antioxidant activities, antibacterial effects (against food-borne pathogens), and color properties as well as identifying the presence of various functional groups (based on FTIR spectra) in two of the widely distributed ornamental flowering plants: H. rosa-sinensis (red colored flowers) and S. bicapsularis (yellow colored flowers). It is anticipated that results generated from this work will provide a suitable base in the use of these flowers as a natural additive or for bio-fortification while developing novel functional foods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Samples

Fresh flowers of hibiscus (H. rosa-sinensis) and Cassia (S. bicapsularis) with no apparent physical, insect or microbial damage were collected from the University garden of Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang. The flower petals were carefully removed (without anther, stamen or sepals) and were freeze-dried (freeze dryer Model, LD53, Kingston, New York) for 48 h at −50 °C. Samples were powdered (mesh size 30), covered with aluminum foil (to avoid exposure to light) and stored at 4 °C until analysis (performed within 24 h).

2.2 Antioxidant analysis

2.2.1 Extract preparation

Distilled water and ethanol (99.7%) were used as solvents for extraction of antioxidant compounds. A known weight of the powdered sample was mixed individually with the solvent (500 mg extracted in 50 mL, as 3 individual replicates) and was shaken in an orbital shaker (Lab Companion, Model SI 600R Bench top shaker) at 160 rpm for 24 h at room temperature. Extracts were filtered through Whatman filter paper (Whatman No. 41, UK). All the filtrates were collected and transferred to screw-top glass bottles (with Teflon caps) and were covered with aluminum foil to avoid exposure to light.

2.2.2 DPPH radical scavenging activity and ferric reducing antioxidant power assay (FRAP)

The capacity of the flower extracts to scavenge DPPH radicals (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) was measured based on the method described by Sanchez-Moreno et al. (1998). The results obtained were expressed as the percentage inhibition of DPPH based on the following formula: where Acontrol is the absorbance of the DPPH solution without sample extract and Asample is the absorbance of the sample with DPPH solution.

For FRAP assay, a modified method described by Benzie and Strain (1996) was adapted to measure the ability of extracts to reduce ferric ions. Ferrous sulfate solution (concentration ranging from 0.1 to 1 μM) was used for preparing the standard calibration curve. FRAP activity was expressed as micromoles of Fe (II)/100 g of dry weight of samples.

2.2.3 Determination of total phenolic content, tannins, flavonoids and flavonols

The total phenolic content of the flower extracts were determined based on the Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) method (Singleton and Rossi, 1965). In brief, 400 μL of the sample extract was mixed with 2.0 mL of FC reagent (10 times pre-diluted). Further, after incubation for 5 min at room temperature, 1.6 mL of (7.5%, w/v) sodium carbonate solution was added and the solution was mixed thoroughly and incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Followed by this, absorbance was measured using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-160A, Kyoto, Japan) at 765 nm. A suitable calibration curve was prepared using standard gallic acid solution. All the results were expressed as mg Gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of sample.

For total tannins, the vanillin–HCl method was employed (Bhat et al., 2007). Briefly, 1 mL of the sample extracts was treated with 5 mL of reagent mixture (4% vanillin in methanol and 8% concentrated HCl in methanol, 1:1 ratio). The color developed was read after 20 min. at 500 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-160A). Suitable standard calibration curve was prepared using catechin (20–400 μg/mL) and results were expressed as mg Catechin equivalent (CE) per 100 g dry weight of the samples, respectively.

Total flavonoids in the sample extracts were determined using the aluminum chloride method as described in the report of Liu et al. (2008). In brief, for 500 mL of the sample extract solution, 2.5 mL of distilled water and sodium nitrite solution (5%, w/v, 150 mL) were added to the mixture. This mixture was maintained for 5 min., followed by addition of 300 mL of aluminum chloride (10%, w/v) and again incubated for 6 min. Followed by this, 1 mL of sodium hydroxide (1 M) was added and the mixture was diluted with 550 mL of distilled water. This solution was mixed vigorously and the absorbance of the mixture was measured immediately at 510 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-160A, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Results of the total flavonoid content were expressed as mg Catechin equivalents (CE) per 100 g of dry weight of the sample.

Total flavonols in the sample extracts were evaluated based on the method described by Miliauskas et al. (2004) with slight modifications. Briefly, 1 mL of 0.15–0.05 mg/mL quercetin methanol solution with 1 mL of 2% aluminum trichloride and 3 mL of 5% sodium acetate were mixed to obtain a quercetin calibration curve. After 150 min and incubation at 20 °C, the absorption was read at 440 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-160A). This procedure was repeated using 1 mL of the sample extract (1 mg/mL) instead of quercetin solution. Results obtained were expressed as mg Quercetin equivalent (QE) per 100 g dry weight of samples.

To determine total anthocyanins, the spectrophotometric method detailed by Abdel-Aal and Hucl (1999) was employed. Briefly, anthocyanins were extracted using acidified methanol (methanol and 1 M HCl, 85:15, v/v) with a solvent to sample extract ratio of 10:1. This was centrifuged and the absorbance was measured at 525 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (UV-160A, Shimadzu, Japan) against a reagent blank. Cyanidin-3-glucoside (5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 mg/L, r2 = 0.9982) was used to prepare for the standard calibration curve. Total anthocyanin contents in the flower extracts were expressed as mg cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalents (c-3-gE) per 100 g dry weight of samples.

2.3 Antibacterial susceptibility test (agar disk diffusion method)

2.3.1 Microorganisms and growth conditions

A total of eight food-borne pathogenic bacteria (obtained from the culture collection of the Food Microbiology Laboratory, School of Industrial Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia) was used for evaluating the antibacterial activities of the flower extracts. Four Gram-positive (Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes) and four Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella enteritidis, Klebsiella pneumoniae) bacteria were used to determine antibacterial properties of flower extracts. Pathogens obtained from respective glycerol stock cultures were inoculated (1%, v/v) into Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) media followed by incubation at 37 °C (for 18 h) to activate cultures. All the tested pathogens were standardized to a concentration of 108 CFU/mL for antibacterial susceptibility test.

2.3.2 Extract preparation for microbial analysis

Extraction using either distilled water or ethanol (99.7%) was performed following the modified method described by Alade and Irobi (1993). Briefly, 1.0 g of each powdered sample was soaked individually in 100 mL of distilled water or ethanol and mixed thoroughly using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature for 3 h. After filtration, the residues were again soaked in 100 mL of the solvent for re-extraction for 12 h. The filtrates were pooled together followed by filtering using Whatman filter paper (Whatman No. 41). The alcoholic filtrates obtained were concentrated using a rotary vacuum evaporator (Rotary evaporator IKA, Model RV06-M1-1-B, IKA-WERKE, Germany) at 50 °C under room atmospheric pressure (approximately 100 kPa), while aqueous filtrates were evaporated under pressure of 43 kPa at 40 °C. A stock solution of 100 mg/mL was prepared by dissolving the semi-solid materials of each crude extract in the solvent used in extraction and stored at −20 °C until further use in the disk diffusion assay.

2.3.3 Culture preparation

Suspension of tested pathogens (108 CFU/mL) was spread on BHI agar (using sterile-glass hockey stick) to ensure even distribution of the suspension on the agar plate. The agar plates were left to be fully diffused after each application. Based on the modified agar disk diffusion method (Washington, 1981), inhibitory potential of microbial growth was determined. Sterile blank paper disks (Oxoid, England, 6 mm diameter) were impregnated with 50 μl of the extracts (100 mg/mL and 50 mg/mL), left to be dried and gently pressed on the inoculated agar plates. Distilled water and ethanol served as the negative control while chloramphenicol (Oxoid, England, 10 μg/disk) served as positive control. Agar plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Antibacterial activity was determined by measuring the diameter of the clear zones of inhibition.

2.4 Color analysis

The powdered samples of flowers were subjected to color analysis using a colorimeter (Minolta, Spectrophotometer CM-3500d, Japan). Powdered samples were placed individually in the specimen cell for measurements. Minolta color scale was used to measure the lightness, which was indicated by L∗ value [L∗ = 0 (black) to L∗ = 100 (white)]. The a∗ and b∗ values that shift from negative to positive values are an indication of the shift from bluish-green to purplish-red and from blue to yellow, respectively.

2.5 Fourier transform infrared radiation (FTIR) analysis

FTIR spectra were obtained from KBr pellets prepared using 1.0 mg of powdered flower samples. The pellets were analyzed in the absorption mode of FTIR and all spectra were recorded from 4000 to 500 cm−1 at a data acquisition rate of 2 cm−1 using a FTIR spectrophotometer (System 2000, Perkin Elmer, Wellesly, MD, U.S.A.).

2.6 Chemicals and reagents

All the chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) or from Fluka (Switzerland).

2.7 Statistical analysis

Results obtained in the present study were analyzed using SPSS software (SPSS Statistics Version 17.0). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the significant differences between sample means, with significant level being considered at P < 0.05. Mean comparisons were assessed by Duncan’s test, with the values expressed as means ± standard deviations. All data presented are mean values of triplicates (n = 3), obtained from three separate runs; unless stated otherwise.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Antioxidant analysis

Results obtained for antioxidant compounds and antioxidant assays are expressed on a dry weight basis (d.w.) (see Table 1). With regard to visual color, ethanol and aqueous extraction of hibiscus and Cassia produced red and yellow colored extracts, respectively. All results expressed are mean of three individual replicates (n = 3 ± S.D.) on dry weight basis. Mean values followed by different letters in a row are significantly different (p < 0.05) from each other.

Parameter

Hibiscus flower extracts

Cassia flower extracts

Ethanol

Aqueous

Ethanol

Aqueous

% DPPH inhibition

83.08 ± 0.1a

97.35 ± 0.6c

99.51 ± 0.2d

96.51 ± 0.3b

FRAP values (μmoles Fe (II)/100 g)

2349.06 ± 228.3ab

2883.23 ± 218.7c

2403.15 ± 307.3b

1966.30 ± 12.7a

Total phenolics (mg GAE/100 g)

4598.16 ± 106.8a

5436.23 ± 168.6b

26223.78 ± 450.3d

9468.18 ± 191.9c

Total tannins (mg CE/100 g)

2849.43 ± 121.1c

4420.87 ± 110.7d

1779.83 ± 139.2b

103.28 ± 6.9a

Total flavonoids (mg CE/100 g)

2155.39 ± 112.6b

2768.06 ± 188.2c

3839.91 ± 162.2d

1133.60 ± 64.9a

Total flavonols (mg QE/100 g)

572.00 ± 1.3c

330.65 ± 2.3b

1293.58 ± 50.8d

22.19 ± 0.9a

Total anthocyanins (mg c-3-QE/100 g)

155.28 ± 5.4c

205.76 ± 3.4d

77.11 ± 4.3b

49.83 ± 3.1a

3.1.1 Percent inhibition of DPPH radical and FRAP assay

Determining antioxidant activity of a sample extract based on the overall scavenging effects of DPPH radical is one of the routinely employed antioxidant assays. This method is considered to be rapid, simple and most convenient. The method is widely accepted as it is independent of sample extracts’ polarity and is effective while screening large volume of samples (Magalhaes et al., 2008; Alam et al., 2012). In the present study, both ethanolic and aqueous extracts of hibiscus and Cassia flowers exhibited rich scavenging effects on DPPH. Overall comparison showed ethanol extracts of Cassia to exhibit stronger scavenging effects on DPPH radicals, while ethanolic extracts of hibiscus had the lowest. Higher radical scavenging activity might be attributed to the presence of high phenolics, tannins or flavonols in the sample extracts.

FRAP assay like the DPPH assay, is considered to be rapid and sensitive and is more of a semi-quantitative assay. In FRAP assay, antioxidant capacity is evaluated based on the capability of the sample extracts to reduce ferric tripyridyltriazine (Fe (III)-TPTZ) complexes to ferrous tripyridyltriazine (Fe (II)-TPTZ). This assay is performed using freshly prepared FRAP reagent consisting of 2,4,6-tris (1-pyridyl)-5-triazine (pH 3.6). A blue product (ferrous–TPTZ complex) is formed due to the reduction of ferric iron in FRAP reagent (Benzie and Strain, 1996). The higher the FRAP value, the greater will be the antioxidant activity of sample extracts. Results obtained revealed hibiscus to exhibit higher reducing power in aqueous extracts compared to ethanolic extract, while in Cassia it was vice versa. For ethanol and aqueous extracts of hibiscus, the reducing powers were 2349.06 and 2883.23 μmoles Fe (II) per 100 g of samples, respectively. In Cassia, reducing power of ethanolic and aqueous extracts were 2403.15 and 1966.30 μmoles Fe (II)/100 g, respectively.

These results are on par with earlier reports on various flower extracts, which have been shown to exhibit high antiradical activities (Özkan et al., 2004; Wijekoon et al., 2011).

3.1.2 Total phenolic content, tannins, flavonoids, favonols and anthocyanins

Plant based phenol compounds exhibit rich antioxidant activity by scavenging the free radicals generated during the normal metabolism process. This group encompasses a wide diversity of compounds, which mainly includes: flavonoids and pro-anthocyanidins (condensed tannins) (Shahidi and Naczk, 2004). In the present study, the amount of total phenolics significantly varied between the two flower extracts and was dependent on the solvents used for extraction. Total phenols ranged between 4598.16 to 26223.78 mg GAE/100 g (see Table 1). Both ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Cassia and hibiscus had high phenolic content with ethanolic extracts of Cassia exhibiting the highest.

In both the flower extracts, amount of tannins differed significantly and ranged between 103.28 to 4420.87 mg CE/100 g (see Table 1). The aqueous extract of hibiscus showed higher tannins, while aqueous extract of Cassia had the lowest. Tannins in hibiscus flowers extracted in ethanol and water were higher compared to Cassia. Presence of tannins (high molecular weight phenols) in adequate amounts can be advantageous as they are able to quench free radicals very effectively, which in turn depended on the number of aromatic rings, molecular weight, and nature of the hydroxyl group substitution (Cai et al., 2006).

With regard to total flavonoid or bio-flavonoid content, hibiscus showed high content in aqueous extracts (2768.06 mg CE/100 g) compared to ethanolic extracts (2155.39 mg CE/100 g). In Cassia, total flavonoids were higher in ethanolic extract (3839.91 mg CE/100 g) compared to aqueous extracts (1133.60 mg CE/100 g). Flavonoids possess rich antioxidant properties and are produced as natural secondary metabolites in plants that encompass 6 sub-classes such as: isoflavones, flavonols, flavones and anthocyanins which vary in their structural characteristics. These flavonoids are capable of effectively interact and scavenge free radicals, which damage cell membranes and biological molecules (Rice-Evans and Miller, 1997).

Total flavonols, which are the most widespread sub-class of flavonoids in plant-based food-stuffs significantly varied between the flowers and their extracts. High flavonol content was recorded in ethanolic extracts of Cassia (1293.58 mg QE/100 g), while its aqueous extract had the lowest (22.19 mg QE/100 g). Similar trend was observed in hibiscus, indicating ethanol to be more suitable for extracting flavonols compared to distilled water.

With regard to total anthocyanin content, between the two flower extracts, hibiscus exhibited a higher value in both extracted solvents compared with Cassia. In hibiscus, high total anthocyanin were recorded in aqueous extract (205.76 mg c-3-gE/100 g) compared to ethanolic extracts (155.28 mg c-3-gE/100 g). Whereas, in Cassia, ethanolic extracts had higher total anthocyanin than aqueous extracts (77.11 and 49.83 mg c-3-gE/100 g, respectively). Of late, anthocyanins are becoming increasingly important not only due to their antioxidant properties, but also because of their antibacterial properties and use as a natural food colorant (Naz et al., 2007).

Presence of high level of total phenols, flavonols, flavonoids, and anthocyanins has been reported in different flowers and their extracts (Cai et al., 2004; Gouveia et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2012; Wijekoon et al., 2011), thus supporting the results and observations done in this study. Additionally, studies have reported a positive correlation to occur between antioxidant compounds and antioxidant activities in plant parts (e.g. flowers, fruits, leaves, seeds) and their extracts (Shyu et al., 2009; Wijekoon et al., 2011; Voon et al., 2012). Earlier, it has been reported that different solvent extraction systems can contribute significantly to differences in the antioxidant activities of the extracts (Tian et al., 2009; Wijekoon et al., 2011), which holds true in the present study also. Overall, our results clearly illustrated that phenols including flavonoids, tannins, flavonol and anthocyanins are most probably the major contributor to the observed antioxidant properties in both hibiscus and Cassia flower extracts.

3.2 Antibacterial activity assay

Table 2 shows results obtained for the antibacterial activity of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of hibiscus and Cassia flowers against various Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. Results showed aqueous and ethanolic extracts of hibiscus flowers (at the concentration of 100 and 50 mg/mL) to selectively inhibit the growth of S. typhimurium and S. aureus, respectively. On the other hand, both the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Cassia (at the same concentration levels) inhibited the growth of B. cereus and K. pneumoniae. However, none of the tested sample extracts showed inhibitory effects against B. subtilis, E. coli, L. monocytogenes and S. enteritidis. Overall, the zone of inhibition ranged from 9–14 mm and 7–9 mm for hibiscus and Cassia extracts, respectively. a: Concentration of 100 mg/mL; b: concentration of 50 mg/mL; disk diameter – 6 mm. –: No inhibition zone.

Microorganisms

Hibiscus

Cassia

Antimicrobial disk

Aqueous extract

Ethanolic extract

Aqueous extract

Ethanolic extract

Chloramphenicol

Zone of inhibition (mm)

a

b

a

b

a

b

a

b

10 μg/disk

B. cereus

–

–

–

–

8.0

7.0

7.0

7.0

14

B. subtilis

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

23

E. coli

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

16

K. pneumoniae

–

–

–

–

9.0

7.5

7.0

7.0

13

L. monocytogenes

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

29

S. enteritidis

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

22

S. typhimurium

11.5

9.0

–

–

–

–

–

–

21

S. aureus

–

–

14.0

12.0

7.0

–

–

–

20

Reports available have shown crude plant extracts to exhibit higher antibacterial activities against Gram-positive bacteria than Gram-negative bacteria (Kabuki et al., 2000; Tian et al., 2009). This has been attributed to structural variations observed in the bacterial cell envelope (including those of cytoplasmic membrane and cell wall components) between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Silhavy et al., 2010). However, in the present study, flower extracts of Cassia inhibited both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens equally.

Polyphenols, flavonoids and tannins present in a sample might be responsible for the observed antibacterial activity. These compounds are generally produced by plants as a mode of defense against microbial infections. Earlier, scientific evidences have highlighted tannins to be more effective against bacteria, yeasts and fungi (Scalbert, 1991). This was attributed to the complexes formed between tannins and microbial enzymes and cell envelope transport proteins. This complex eventually is believed to result in the inactivation of proteins resulting in inhibition of microbial growth (Haslam, 1996). Furthermore, essential oils present in the samples can also contribute substantially for the antibacterial activities (Voon et al., 2012).

Based on the available reports, methanol extracts have been shown to result in high extraction yields with strong antibacterial activities (Quarenghi et al., 2000; Mann et al., 2011; Jo et al., 2012). However, as methanol is highly toxic to humans and livestock consumption and being a non-food grade solvent it is rather worthy to evaluate the activities in ethanol or aqueous extracts, which can also exhibit appreciable antibacterial activities and can be considered much safer. Results generated by using these ethanol or water extracts can be more beneficial for food and pharmaceutical applications compared to methanol or other solvents.

3.3 Color analysis

In the present study, lightness (L∗) value of hibiscus and Cassia was 37.08 and 60.11, respectively. Low L∗ value of hibiscus might be attributed to the dark color of its flower petals compared to Cassia (Table 3). For hibiscus, its chromatic component (a∗ and b∗) values were 10.83 and 3.71, respectively and were lower than the value of Cassia, which were 24.80 and 61.04. a∗ and b∗: Chromatic components; aLightness; bChroma = (a∗2 + b∗2)1/2; cHue angle = arc tangent (b∗/a∗). All results expressed are mean of three individual replicates (n = 3 ± S.D.) on dry weight basis. Mean values followed by different letters in a row are significantly different (p < 0.05) from each other.

Analysis

Hibiscus

Cassia

L∗

37.08 ± 0.02x

60.11 ± 0.02y

a∗

10.83 ± 0.07x

24.80 ± 0.03y

b∗

3.71 ± 0.02x

61.04 ± 0.10y

C∗

11.45 ± 0.06x

65.88 ± 0.11y

Δh

18.87 ± 0.05x

67.89 ± 0.01y

Chroma (C∗) and hue angle (Δh) values are obtained from a∗ and b∗. Chroma and hue values of hibiscus were 11.45 and 18.87 while for Cassia, its chroma and hue values were 65.88 and 67.89, respectively. Chroma represents intensity of the color, while hue angle values are stepped counter clockwise from red to purple (Δh = 0) across a continuously fading color circle through 90° (yellow), 180° (bluish-green) and 270° (blue). Hibiscus showed lower chroma and hue angle values, which indicates that it has less intense colored flower petals, while Cassia had more vivid yellow colored flower petals, which are due to its high chroma and hue angle values. Overall, the color of hibiscus was dark (low L∗ value), but with low intensity (less vivid). On the other hand, the color of Cassia was light (high L∗ value) but with high intensity (very vivid).

Generally, in nature, a diversified group of flavonoids, anthocyanins, chlorophyll, xanthones, and betalains can contribute to the intense floral color (Brouillard and Dangles, 1993). Differences in the floral color depend entirely on the extent of co-occurrence with other coloring or pigment compounds and factors like chemical nature of pigments, their acylation and methylation status, pH of the vacuole, accumulation of the cyanidins or pelargonidin derivatives, and genetic inheritance (Gettys and Wofford, 2007).

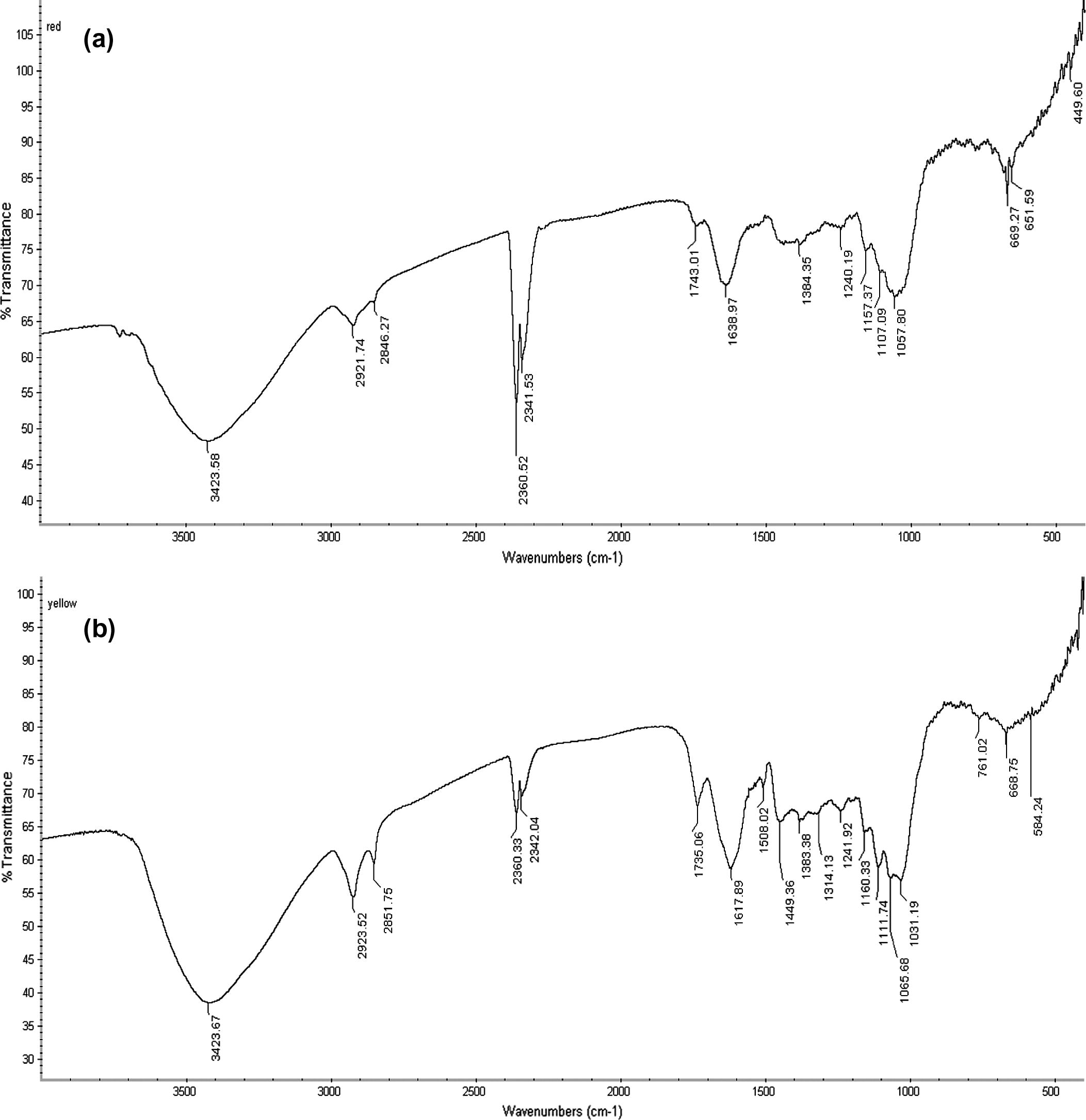

3.4 FTIR analysis

FTIR spectra and the functional group of compounds present in the powdered flower petals of hibiscus and Cassia are shown in Fig. 1(a) and (b) and Table 4, respectively. Spectral analysis revealed hibiscus and Cassia to be almost identical and the major functional groups included: polysaccharides, suberin, and lipid. In Cassia, the spectral peak slightly differed from hibiscus with some additional peak at 1449.36 cm−1 (lipid origin), and CH2 wagging band progression and glycogen at 1314.13 and 584.24 cm−1, respectively. Also, FTIR spectra of both samples showed peaks in the range of 3420–3429 cm−1 which could be the OH group of the phenolic compounds present in the samples (Shurvell, 2002; Tejado et al., 2007). However, it is noteworthy to mention here that results obtained in FTIR alone are not sufficient to prove the existence of compound-classes, especially when it comes to mixtures of many different compounds. –: no peak wavenumber. (Source: Schwanninger et al., 2004; Bhat, 2011).

a, FTIR spectra of powdered flower petals of hibiscus; b, FTIR spectra of powdered flower petals of Cassia.

Frequency range (cm−1)

Peak wavenumber (cm−1)

Functional group and origin

Hibiscus

Cassia

3420–3429

3423.58

3423.67

O–H stretch, Polysaccharides

2923–2925

2921.74

2923.52

Asymmetric C–H vibration, Suberin

2852–2854

2846.27

2851.75

Symmetric C–H vibration, Suberin

1739–1745

1743.01

1735.06

Ester C⚌O stretch, lipid, triglycerides

1449–1459

–

1449.36

Lipids

1312–1315

–

1314.13

CH2 wagging band progression

1159–1172

1157.37

1160.33

Asymmetric C–O–C vibration, Suberin

1110–1116

1107.09

1111.74

C–C and C–O stretching, Polysaccharide

1037–1066

1057.80

1065.68

C–O valence vibration, Polysaccharide

576–589

–

584.24

Glycogen

In conclusion, results of this study showed hibiscus and Cassia flowers to encompass significant amount of antioxidant compounds, with the extracts exhibiting rich antioxidant activities. In addition, both the flower extracts also possessed antibacterial activity against various Gram-positive and Gram-negative food-borne bacterial pathogens. Results on antioxidants and antibacterial activity indicate the prospective of utilizing hibiscus and Cassia flower extracts as a mode of natural food preservative. Results on color analysis highlight the potential of utilizing these flowers as a natural food colorant. With regard to functional group of compounds, both the flowers showed the presence of polysaccharides, suberin and lipids/triglycerides. All the findings of the present study warrant further research wherein hibiscus and Cassia flowers need to be explored commercially as a low-cost, natural preservative during the preparation of novel functional foods or in nutraceutical applications.

Acknowledgements

Individual research funding provided as RU grants (No. 1001/PTEKIND/814139, USM) for the corresponding author is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- A rapid method for quantifying total anthocyanins in blue aleurone and purple pericarp wheats. Cereal Chemistry. 1999;76:350-354.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activities of crude leaf extracts of Acalypha wilkesiana. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1993;39:171-174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.N., Bristi, N.H., Rafiquzzaman, M., in press. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal doi: org/10.1016/j.jsps.2012.05.002.

- The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of antioxidant power: the FRAP assay. Analytical Biochemistry. 1996;239:70-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of ionizing radiation on antinutritional features of velvet bean seeds (Mucuna pruriens) Food Chemistry. 2007;103:860-866.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential use of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy for identification of molds capable of producing mycotoxins. International Journal of Food Properties 2011

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extraction and characterization of some natural plant pigments. Industrial Crops and Products. 2012;40:129-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flavonoids and flower colour. In: Harborne J.B., ed. The Flavonoids: Advances in Research since 1986. London, UK: Chapman and Hall; 1993. p. :565-588.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sciences. 2004;74:2157-2184.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure–radical scavenging activity relationships of phenolic compounds from traditional Chinese medicinal plants. Life Science. 2006;78:2872-2888.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inheritance of flower color in pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata L.) Journal of Heredity. 2007;98:629-632.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts from flowers of Andryala glandulosa ssp. varia (Lowe ex DC.) R.Fern., an endemic species of Macaronesia region. Industrial Crops and Products. 2013;42:573-582.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of botanicals as natural preservatives in food. In: Bhat R., Karim A.A., Paliyath G., eds. Progress in Food Preservation. UK: Wiley Blackwell Publishers; 2012. p. :513-524.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural polyphenols (vegetable tannins) as drugs: possible modes of action. Journal of Natural Production. 1996;59:205-215.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and tyrosinase inhibitory activities of methanol extracts from Magnolia denudata and Magnolia denudata var. purpurascens flowers. Food Research International. 2012;47:197-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of novel antimicrobial compounds from mango (Mangifera indica L) kernel seeds. Food Chemistry. 2000;71:61-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of methanolic extract of emblica fruit (Phyllanthus emblica L.) from six regions in China. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2008;21:219-228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methodological aspects about in vitro evaluation of antioxidant properties. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2008;613:1-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of Bombax buonopozense P. Beauv. (Bombacaceae) edible floral extracts. European Journal of Science. 2011;48:627-630.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of radical scavenging activity of some medicinal and aromatic plant extracts. Food Chemistry. 2004;85:231-237.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity directed isolation of compounds from Punica granatum. Journal of Food Science. 2007;72:341-345.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in the rat by H. rosasinensis anthocyanin extract administered in ethanol. Toxicology. 1998;131:93-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Rosa damascena flower extracts. Food Science and Technology. 2004;10:277-281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of flowers from Anthemis cotula. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:710-712.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and isoflavonoids. In: Rice-Evans C.A., Packer L., eds. Flavonoids in Health and Disease. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bio-colorants and its implications in health and food industry – a review. International Journal of PharmaTech Research. 2011;3:2228-2244.

- [Google Scholar]

- A procedure to measure the antiradical efficiency of polyphenols. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1998;76:270-276.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of short time ball milling on the shape of FT-IR spectra of wood and cellulose. Vibrational Spectroscopy. 2004;36:23-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenolics in Food and Nutraceuticals. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. pp. 1–576

- Spectra-structure correlations in the mid- and far-infrared. In: Chalmers J.M., Griffiths P.R., eds. Handbook of Vibration Spectroscopy. UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 2002. p. :1783-1816.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antioxidant ability of ethanolic extract from dill (Anethum graveolens L.) flower. Food Chemistry. 2009;115:515-521.

- [Google Scholar]

- The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2010;2:a000414.

- [Google Scholar]

- Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic–phosphotungstic acid reagents. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1965;16:144-158.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physico-chemical characterization of lignins from different sources for use in phenol-formaldehyde resin synthesis. Bioresource Technology. 2007;98:1655-1663.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of consecutive extracts from Galla chinensis: the polarity affects the bioactivities. Food Chemistry. 2009;113:173-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of natural antimicrobials for food preservation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2009;57:5987-6000.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flower extracts and their essential oils as potential antimicrobial agents. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2012;11:34-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory Procedures in Clinical Microbiology. New York, USA: Springer Verlag; 1981.

- Effect of extraction solvents on the phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of bungakantan (Etlingera elatior Jack.) in florescence. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2011;24:615-619.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant effect and active components of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) flower. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2012;50:3056-3061.

- [Google Scholar]